Tran Thi Van laughingly thrusts a plastic container in our direction, urging us to look more closely. We oblige and find ourselves staring at a heap of dead, black bugs, vaguely reminiscent of dung beetles. Van exchanges the container for a small vial containing a clear liquid for us to smell. It exudes a heady, sweet perfume. ‘It’s the real thing! One drop off the top of a chopstick is enough,’ she explains of the special seasoning that is added to the dipping broth for banh cuon, the stuffed rice-paper pancakes she prepares at her shop.

The liquid, called ca cuong, is a pheromone produced by the giant water bug (lethocerus indicus), which lives in the rice paddies, ponds and streams of South-East Asia. In the past, country folk would attract the bugs at night with a torch or lantern, and drain the liquid from their bodies. Once very common, the giant water bug is now relatively rare and while Van prides herself on using the real beetle juice, most of the ca cuong in the market is a synthetic copy that is produced in Thailand or China.

Van takes back her precious vial and returns to her steamers to fill another order. The cooking station outside the open shopfront is well set up: two steamers covered with cloth stretched tight as a drum, and a pot with the rice batter in front. On a low table, the fillings and toppings are ready in stainless steel bowls.

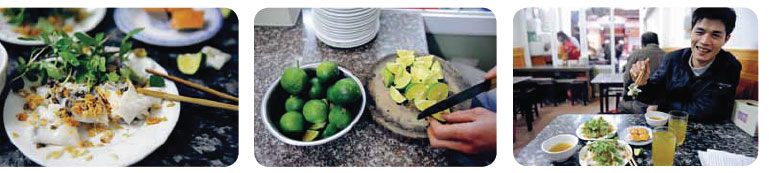

Years and years of making 600 to 800 banh cuon a day has ingrained the process in Van’s body memory. She works fluently and with the utmost efficiency: ladling the batter onto the steamer, smoothing out the mixture with the base of the ladle, covering it with a lid to allow the crepe-like pancake to cook evenly, and finally lifting it with a flattened bamboo stick and carefully transferring the gossamer-thin sheets onto a greased tray. There, the filling of mushroom and pork is added, the pancake is rolled up and cut into chopstick-size pieces, then topped with deep-fried shallots and shredded prawns.

The dish is served with a broth flavoured with fish sauce for dipping and with a side of cha que, a cinnamon-spiced meatloaf, easily recognisable because of its orange-hued skin.

Now in her mid-fifties, Van is the third generation of her family in the banh cuon business. At the age of thirteen, she started helping at her mother’s small shop in Thuoc Bae Street. Her mother passed away in 1973 and Van took over not long after her eighteenth birthday. ‘I was the oldest of five children and had to take care of the family,’ she says matter-of-factly.

The first two decades at the helm of the family business proved to be very difficult. The shop had to change address a number of times, and during the lean years between 1975 and the late 1980s, when food was rationed, rice was particularly hard to come by. Many of her customers were also so short of money that they resorted to bartering for their fix of the filled rice pancakes. However, Van’s determination to continue with her trade worked out in the end.

Almost twenty years ago she moved to her present location in Hang Ga Street in Hanoi’s old quarter, continuing to make her pancakes with the help of her now grown-up children. The only child not helping in Van’s shop is her son, who, with her support, has set up his own shop in Le Van Huu Street, in the former French quarter.