One of the most valuable skills Pham Van Hue learnt in the army was to make dough. Born and bred in Hanoi, Hue spent six years as a soldier in the south of the country, from 1977 to 1983, during which time he was also briefly stationed in Ho Chi Minh City. There, in the suburb of Cholon, he befriended a Chinese man who made and sold quay, the deep-fried bread that normally accompanies pho. Hue was intrigued and left the south with the ability to make the simple dough, based on yeast, water and flour.

When Hue was finally released from the army, he went back to his native Hanoi and married his high-school sweetheart, Phuong. Life was hard for the newlyweds in the austere years after the end of the American War, as the Vietnamese call the Vietnam War. Hue worked in a laundry and Phuong in a state-owned carpet-weaving company, but their combined income barely made ends meet.

In order to supplement their salaries they decided to set up a dumpling-making business. Hue already knew how to make the dough and together they experimented until they had perfected the filling: a boiled quail egg inside a mixture of minced pork, rice vermicelli and wood ear mushrooms.

For the first few years they worked from their home, preparing dumplings for restaurants while keeping their day jobs. But in 1990, after the post-war restrictions on opening small businesses had been lifted, they quit their jobs and set up a stall near their house in Pho Duc Chinh. Phuong and Hue have been selling their dumplings from that location ever since.

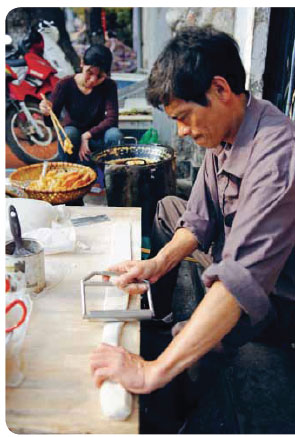

It is hard to imagine a stall set-up any simpler than theirs: two rickety benches, an odd assortment of plastic stools, a wok set over a charcoal brazier for deep-frying, some mismatched plastic crockery and cutlery.

Phuong’s workday starts at 7 am when she goes to the market. ‘I have to go early to get the best cuts of pork,’ she says. At home she minces the meat herself, cooks the eggs and prepares the green papaya dipping sauce before making lunch for the family. After lunch, the preparations continue on the street. Making about 200 dumplings a day, the husband-and-wife team observe a strict division of labour. Hue rolls out the dough he has prepared earlier, Phuong encloses the filling and briefly fries the dumplings before placing them in a big bamboo basket.

Around midafternoon customers start to appear: factory workers who have finished their shifts, and students on their way home from school. Most buy a couple of dumplings, reheated and wrapped in newspaper: a cheap and tasty takeaway snack to tide them over until dinnertime.

‘When we first started here, twenty years ago, we were the only ones selling food in the street. It was very quiet,’ Hue explains. ‘Now there’s competition from restaurants and other street food stalls.’ Not that Phuong and Hue have a lot to worry about. Competitively priced at 5000 dong (25 cents) a dumpling, they usually sell out of their delicious banh bao by nightfall.