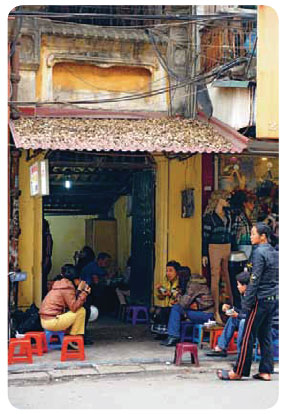

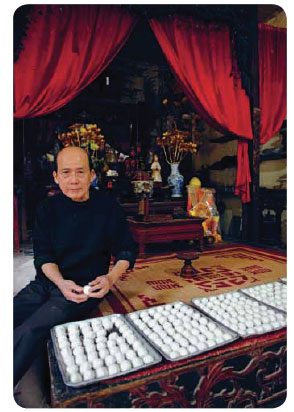

Pham Bang is as close as one gets to Hanoi royalty. The eighty-year-old actor is the fourth generation of his family to be born in the historic old quarter, and for the last sixty years he has lived in the same building in Hang Giay Street. Well-loved by the locals for his comedy skits, which air every weekend on both national and local television stations, the sprightly octogenarian is also famous for selling sweet dumplings. Almost every afternoon he sets up shop in front of the wooden gate leading to his upstairs room in the back building of a typical old-quarter house.

Born into a solid middle-class family with both parents working as school teachers, Bang grew up in colonial times and speaks fluent French. He caught the acting bug early in life and recalls how unhappy his parents were with his choice of career. Their worries seemed to bear out when, after twenty years in the acting business, his career couldn’t support him and his family.

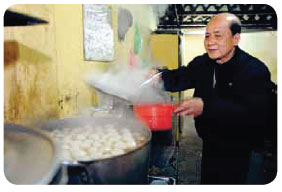

In the late 1970s, Bang urgently needed an additional source of income and he turned to dumpling making. For a short time he worked with a Chinese business partner, but as the Chinese left the area, he struck out on his own. ‘Basically I am self-taught and it took me four years to perfect my recipe for banh troi,’ Bang says proudly. The effort paid off and his stall is well known beyond the local area, and not just because of its famous proprietor.

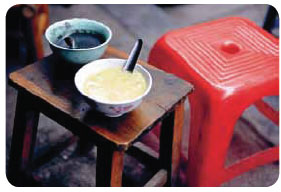

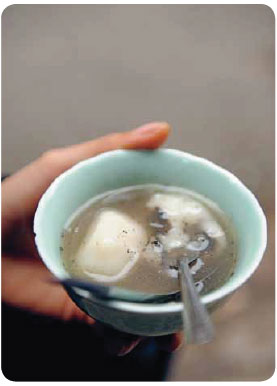

‘The secret to a good banh troi lies in the consistency of the dough,’ says Bang, who adds a small amount of regular rice flour to the glutinous rice flour. He uses 20 to 30 kilograms of flour a day, and starts making his dough just after sunrise. By midmorning most of the available surfaces in the large room Bang occupies are covered with trays of raw dumplings, ready for the steamer. Bang makes two types of dumpling: one filled with grated coconut, the other with black sesame seeds. Customers get one of each type per serve unless otherwise requested.

While acting alone couldn’t pay the bills in the 1980s and early 1990s, Bang’s fame as an actor not only promoted the stall, but also helped him keep it going through the difficult bao cap time of food rationing. Vietnam’s economy, along with Bang’s professional situation, improved over the next two decades. Bang could have retired from dumpling making a long time ago, but the small section of footpath remains his personal stage. ‘I also do it,’ he says, ‘out of respect for the trade that allowed me to carry on as a performer.’

It looks like the twin traditions of cooking and acting are set to continue. Out of his four children, only one has chosen a career in the world of business. Two of his daughters have become actresses, and the third is helping Bang keep the stall going.