No one could claim that evocations of dead or dying women were lacking in art and literature before the end of the eighteenth century. An ancient Greek genre of funerary epigrams spreads its imagery of brides perishing in the depths from antiquity to the ages beyond. An epitaph by Xenocritus of Rhodes reads,

Your hair rushes still through the salty waters, oh/

Lysidice, young maid perished at sea … /

A bitter sorrow for your father, who, in leading you to your groom/

has brought him neither a wife nor a corpse.

Quoted in Chénier, 847

Or there is the doomed Ophelia, found in the “weeping Brooke,” whose

garments heavy with their drink/

Pulled the poor wretch from her melodious lay/

To muddy death./

Hamlet, IV.vii

In France we have only to think of the grandiose death scene of Racine’s guilt-ridden, incest-obsessed Phèdre, imbibing the magic potion devised by Medea, which darkens her sight forever, as the light of the world returns (Phèdre, V.vii). A fascination with female frailty certainly recurs in western art with some reliability over the centuries, remaining one of the stock of topoi available to it. But no glut of such foredoomed figures exists in modern times before the waning of the Age of Enlightenment and in the century that copes with this heritage. As we consider the era of Chardin, Watteau, Boucher, and Fragonard, to cite only the most celebrated of the painters, we find no brooding preoccupation with female dismay, disease, and death. The literary works of the earlier half of the century, which often explore the tensions of female subordination with some intensity,1 display a greater range of complexity in their portrayals of women. While Montesquieu’s Roxane or Prévost’s Manon Lescaut do, of course, die, their struggles tend to center around selfhood or self-interest. No established fictional or artistic obsession with female weakness as yet asserts itself there.

It is the phenomenon of an increased concentration upon sacrificial female figures in the decades preceding and in the years following the revolution that I would like to explore here.

I will consider figures of sacrificial or sacrificed women, whether at bay, engulfed, dying, or dead interchangeably in my chapter, for I regard them as belonging to a single order of representation. The artistic phenomenon I broach here has previously been subsumed as a feature of the rise of Romanticism, or of gothicism. Such perspectives are perfectly viable, but they tend to leave out of explicit account the relationship between the gender discourse transmitted by art and that of society. This is the gulf I hope to bridge here, in a political reading for their gender implications of familiar texts. The evolution I intend to portray, which reaches from the 1760s to the start of the Napoleonic Empire, overflows the boundaries of political revolution, preceding and outlasting it. Its dynamics lie in the domain of eroticism and power, and they cannot be fully subordinated to the logics of social, political, or economic structures because they possess an illogic of their own. What I ask here is, did this evolution bear any relationship to the fate of women in the revolution? Could it, in its inherent violence, have been the sign of a more pervasive gender malaise, a factor that might even have contributed to the etiology of revolution?

The culture in question here, though it assumes a posture of universality, is essentially a male one. Though it incorporates into its fabric that pronounced female component of manners and dress that has sometimes led to the belief that women’s influence was preponderant, that indeed this very era was “the reign of women,” such a view does not sustain serious scrutiny. While women were invited to consume its products, the ethical and aesthetic systems of value of its works of art reflect a male consensus to which women were able to contribute only episodically, not fundamentally. Even the most eminent women in this era of superb salon figures, such as Mesdames du Deffand, Geoffrin, and Necker or Mlle, de Lespinasse, and accomplished novelists, like Mesdames de Graffigny and Riccoboni, saw themselves essentially as satellite figures to the dominant male literati. Indeed a sense of “foreignness,” an extreme of alienation that even the most august women might experience within the ambience of this male-dominated culture, is expressed by Madame de Graffigny’s Lettres d’une Peruvienne. Such a sense of alienness could only have been heightened by the restructuring of sexual passion by male artists that we witness in the rise of prestige of figurations of engulfed women.

I will focus here on this sole phenomenon: male art’s fascination with sacrifice for love and/or family. In this chapter I will deliberately eschew historical nuance to dwell on the underlying mythical and psychological plane where fantasy constructs its own history. I take as a suggestive point of departure Klaus Theweleit’s view that “in all European literature … desire, if it flows at all, flows in a certain sense through women. In some way or other, it always flows in relation to the image of women” (272). According to this insight, images of women may have power to reveal aspects of the history of gender that history itself shrouds from view. The desire Theweleit alludes to has been defined primarily by the male artists and authors who have been the chief shapers of experience. But as Freud has reminded us—a thing that few among us probably would be moved to deny—the id itself knows no gender. Nevertheless, in the absence of powerful rival articulations by women of their own experience of desire, conceptions of that free-floating charge like those proposed in the works of male artists I discuss below would be understood by women and by men alike as preconditions of a certain style of passion.

We step back momentarily to a longer perspective. The eighteenth century had witnessed so substantial a participation by women in the upper reaches of society that the Goncourt brothers were later to dub it “the century of women.” From Montesquieu to Rousseau and beyond, men continued to raise the issue of women’s influence as a problem to be resolved. As I’ve argued elsewhere,2 a class of “social women” who lived their lives in a worldly sphere—as salon-nières like Madame du Deffand or Madame Geoffrin, influential mistresses to powerful men like la Pompadour or la Du Barry, or simply as less clamorous actors on the social scene—had risen to prominence. The extent and effect of the influence that women actually wielded was, within this period, widely debated and either deplored or praised. In this vein, in Rousseau’s Nouvelle Héloϊse itself—that work which on the surface appears so slavishly to “worship” the female as a principle—Rousseau denounced the women of Paris. Of course he attacked them in the name of his own idea of “the feminine.” Following in his wake, Restif de la Bretonne proclaimed, “It is a crime of infringement against humanity for Men to serve Women, except out of graciousness or protectiveness” (184). The sexual provocativeness of some of these insubordinate women inflamed the ire of the chevalier Feucher d’Artaize, who wrote in his 1786 Reflections of a Young Man that man was in fact defeating himself: in his “laughable submissiveness, his servile and self-serving compliments” to women, he was fostering the destruction of his natural right, “that devouring ardor instinctive in him to command. What a revolution!” he lamented (44).

One woman among those who tried to answer such diatribes, Madame de Coiçy, attempted to reply to the charge of female privilege by putting her own construction upon the case:

They bruit it about that in France women enjoy all there is to be enjoyed; that they are given an excess of honor. France, they say, is the paradise of women: and yet there is no people among whom really and in point of fact, they are more unworthily scorned and mistreated, although they are superior to all the other women of Europe in their talents, their charms of nature, wit, and art. (74)

But her case could not hope to meet the level of an attack, a revealing one to be sure, like Feucher’s: “the corruption of morals is caused by the sex that has most to gain by it, the sex hungriest for pleasure, the more emotional sex, the weaker sex” (1788, 13).

The ascension to social prominence of women took place in a period that was experiencing a dramatic rise in illegitimate births. It tolerated (not without guilt) massive abandonments of infants born outside marriage (of five such infants by Rousseau himself) to foundling homes or wet nurses under whose ministrations a large proportion of them died.3 Prostitution, both cheap and expensive, was rife and on the increase.4 Marriage in the lower classes was a laborious imperative and in the upper, largely dynastic and nominal. The concatenation of social factors has suggested to some that France was enduring serious tension around issues of natality and sexual morality,5 and these are, of course, precisely areas that center on the relations between men and women. The apogee of the age of the libertine, of the petit-maître, makes its own contribution to the coming apart of the sense of the nation as a family of coherent classes with more or less stable family expectations. Women’s new and as yet unintegrated social presence combined with an atmosphere of sexual predatoriness, which attracted many women as well as many men who wished to profit thereby. Together these factors came to represent an impending menace to the social fabric. This sense of menace generated, as we will see in Rousseau’s novel, a moralistic backlash against both the idea of women’s social power and their sexuality. For the masculinist faction, in time-honored fashion, women would ’take the rap’ for human sexuality and the failure to live up to society’s professed moral codes. Public reaction was then to produce a new ideology, a model of woman that was to resemble Rousseau’s Julie in being selfless and sacrificial; yet unlike that philosophe in skirts, this new model was to be stripped of mind, of culture, of language. Akin to Julie as emblem of Nature, the new figuration would incorporate that heroine’s sexually repressed aspect in her assumption of the role of medium between man and God, man and his destiny.6

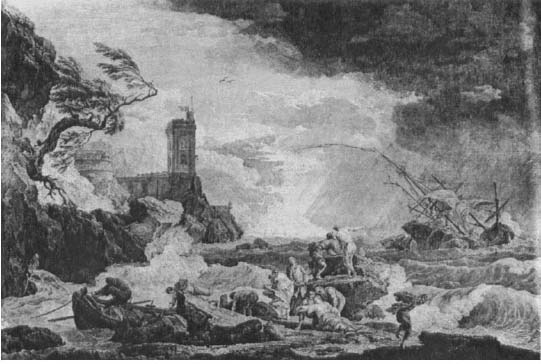

Two eloquent pre-romantic seascapes by Joseph Vernet, both shown in the salon of 1765 and commented upon by Diderot, might serve as tokens of our theme. The Grande Tempête (Figure 11.1) depicts a rocky storm-washed shore, with a capsized vessel blown about by the sea and a wildly buffeted tree standing out scrawnily on its crag. On shore, a handful of survivors or rescuers, among whom we distinguish a seated woman expiring in the arms of two men. Her figure, the foundering ship, and the fragile tree bear all the burden of pathos in the work. We must think of them together, as stricken figures. Diderot remarked, “Look at this drowned woman who has just been drawn from the waters and try to prevent yourself from feeling the sorrow of her husband if you can” (Salons, 122). In the second Vernet book, Shipwreck by Moonlight (Figure 11.2), the sky is clearing. We are in the aftermath of a violent storm. Again we find the capsizing vessel bereft, and at center, a few men working in the debris of the ship’s wreckage. At right, we find the human focal point in a concerned group; a man tries to support a visibly weakened white-clad female figure, as a circle of men looks on. The fireside at which they seek to warm her, the tent, are, like the studied expert efforts of the men in both scenes, symbolic references to the culture men sustain in the face of nature’s awesome depredations. But in both scenes, as the men struggle, the women succumb. As the “nature within culture,” they alone fall easy prey to the wind and water to which they are connected as untamed powers. Woman’s vulnerability has a sexual origin: it leads her to pregnancy and sometimes to death. In her study of medical tracts of this time, Jordanova writes that “women were the carriers and givers of life, and as a result, a pregnant woman was both the quintessence of life and an erotic object” (106). The affect around the female figures in these storm scenes distills masculine awe, anxiety, and ambivalence over the saving of the woman’s life, or experiencing the pathos of seeing her die, a victim of nature’s violent ravages from which the man, in his alliance with culture, has detached himself.

Figure 11.1 Joseph Vernet, La Grande Tempête, Salon of 1765. Source: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Figure 11.2 Joseph Vernet, Shipwreck by Moonlight, Salon of 1765. Source: Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

How do these factors operate within a domestic setting? Carol Duncan has written that Greuze’s painting of the Beloved Mother, also from the 1765 Salon, emphatically affirms that motherhood is blissful (“Happy Mothers,” 572) (Figure 11.3). Yet, as she has seen, the bliss of this mother, though not literally murderous, is a deeply debilitating or at the least highly equivocal state. Diderot accurately read the work: “The mother here has joy and tenderness painted upon her face along with some of the discomfort inseparable from the motion and weight of so many children upon her who overwhelm her, and whose violent caresses would end up distressing her were they to last” (Salons, 143). As if this were not enough to suggest an analogy with bodily assault akin to rape, Diderot stresses how, “It’s that sensation approaching pain, mixing tenderness with joy, and her prone position suggesting lassitude, that half-open mouth,” which provide him, a male observer,7 with such keen pleasure. Greuze’s work confronts us with a dramatic bourgeois scene, an example of this artist’s departure from the predominating mythological or genre conventions. And within this milieu he sets a swarming mass of children’s eyes, arms, hands, all importuning their young, yet overpowered mother. Confirming Jordanova, Duncan points out how often maternity was linked with sexual satisfaction in eighteenth century art (“Happy Mothers,” 572). Here the mother’s vulnerability creates the bond between sexuality and maternity. This is what warms the heart of the male viewer like Diderot. While Greuze’s ideal mother is not dead, nor is she dying, she is engulfed by her procreativity. Hers is the portrayal that will become the political revolution’s ideal for woman: the young mother of a large patriarchal family, seductive in her passive consent to motherhood. Greuze openly displays the Schadenfreude inherent in this model.

Figure 11.3 Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Well-Beloved Mother, Salon of 1765. Source: Laborde Collection, Madrid.

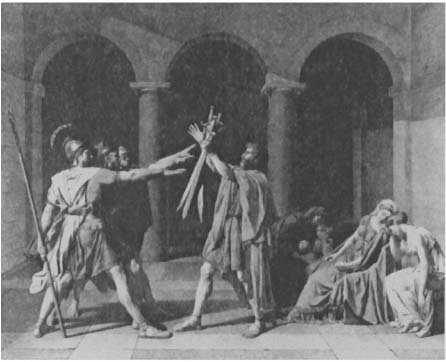

Duncan again provides the most cogent feminist reading of David’s Oath of the Horatii (“Fallen Fathers”) (Figure 11.4). The collapsed female figures seated on the right, including as she has pointed out the young boy who alone of that group is privy to the sight of the oath, form a group of helpless choral weepers, bringing their sighs and lamentations to enrich the emotions of the scene. The thrusting muscularity of male arms and legs is contrasted with the sinuous line of the downcast women. The gender schism here is complete. It could almost be seen, in fact has been seen8 as a 1785 forecast of the Jacobins’ gender policy, allocating to men the public—military, legislative, commercial, and intellectual—realms; to women, the realm of privacy, or the family. David’s vision of Roman male heroism and female frailty are so little accidental that they are recapitulated in his Brutus of 1789, where the father muses in disarray over the sacrifice of his sons to the state, while the female figures, again ghettoized within their space, express open grief with the braided curves of their bodies and gestures, as the mother clasps her daughters, especially the pale and fainting corpselike one—an Ingresque figure—to her breast.

Figure 11.4 Jean-Louis David, The Oath of the Horatii, 1784. Source: The Louvre, Paris.

Despite the force of David’s example, the yield of visual images of dead and dying women is small in the iconography of the revolution. This is because the revolution turned massively to the use of the empowering female figure as allegory, as Lynn Hunt has theorized, to counter and discredit the potent and consecrated imagery of kingship. Gender struggle during the active years of revolution assumed a different dimension, as struggle actualized in the political arena.9 Hunt notes two relevant points: first, that “the proliferation of the female allegory was made possible … by the exclusion of women from public affairs. Women could be representative of abstract qualities and collective dreams because women were not about to vote or govern (“Political Psychology,” 39), and second, that as compared with the English, “French engravers were less free to express their fantasies of power” (36) during this period. Pressures upon these artists were such that they restricted themselves, in a form of self-censorship, to a ready repertoire of set allegories and symbols. Hunt has also claimed that a deliberate political decision appears to have been taken by the Jacobins in 1794 (“Engraving the Republic”) to substitute the male figure of Hercules for the by then stock figures of Liberté or the Republic in a move against feminization of the national symbols. Visual evidence for the years 1789 to 1795 will therefore be elided here. Although these years are the eye of the hurricane of a long evolution, the revolution’s use of allegory poses wholly different questions, too complex to be compassed in this chapter. Some important literary examples of our theme, by Sade and André Chénier, will represent that era. (See below.)

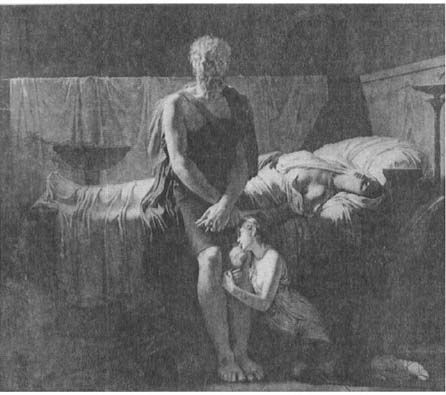

Figure 11.5 Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, The Return of Marcus Sextus, 1799. Source: The Louvre, Paris.

In the period after 1795, with the Directoire, visual images of dead and dying return in force. Among a series of works apparently reflecting the guilt of returning aristocratic émigrés and the rising popularity of the Oedipus and related themes, we find Harriet’s Oedipus at Colonus.10 His Antigone is prostrate, an exhausted, dispirited comforter to her despairing and disabused parent: in him we find an apposite icon of postrevolutionary French manhood, baffled by fate. Guérin’s Return of Marcus Sextus (Figure 11.5) of the same period explores a like scene of domestic tragedy awaiting the returning hero.

We discern a pattern:11 the dispirited, dead, or dying female figure in these works, generally following the visual model of fainting lissomeness given by David, is always young, either maiden or young matron, but always in full sexual bloom. Projections of masculine fears and passions, these figures frequently lack individuation or characterization as images, are generalized, fluid, evanescent, even when depicted as full-bodied.

Figure 11.6 Chevalier Féréol de Bonnemaison, Young Woman Surprised by Storm, 1799. Source: Brooklyn Museum.

Three works, finally, all picturing a watery scene, round off this swift survey: Bonnemaison’s rather Blake-like Young Woman Surprised by Storm (Figure 11.6) of 1799 shows a figure more plainly Gothic in character, at bay before the storm’s ravages, and rigidly clutching at herself as her flimsy gossamer draperies gracefully unfurl to the whipping of the winds: a very emblem of lostness; Gros’s Sapho (1801) casting herself in lovelorn despair from the cliffs at Leucadia, an altogether ghostly apparition (Figure 11.7); and lastly, one of a number of postrevolutionary depictions of flood, this one by Danloux (1802), in which the father has been unable to preserve either his voluptuous young wife or his livid infant from death by drowning (Figure 11.8).

I would like to be able to argue that male artists’ increased production of images of flood reflects a postrevolutionary sense of engulfment, of feeling overwhelmed by the political and natural fates, to which the female figure simply contributes her inevitable quotient of pathos as preordained victim, an allegorical projection and displacement of historically based male disarray onto the figure of the female. This logic proves inadequate, for a prerevolutionary work from 1779, Gamelin’s Flood (Figure 11.9), also depicts a scene of deluge, with the dead beloved, not yet denuded as she will later become, her blond hair and clothing burdening her lifeless form, being dragged from the waters by strong, loving arms as the storm rages about her. So the revolution in the depiction of women did not await the revolution: it decidedly preceded it. Could the two have had anything to do with each other?

Figure 11.7 Baron Antoine-Jean Gros, Sappho at Leucadia, 1801. Source: Musée Baron-Gérard, Bayeux.

Literature helps us make some otherwise obscure connections in this series of related visual constructs of woman. The heroine of his 1761 novel, Rousseau’s powerfully emblematic Julie, who expires from a malady contracted after saving her son from drowning, is the ancestress, spiritually and in her physical fate of these doomed figures of fantasy (Figure 11.10).

Figure 11.8 Henri-Pierre Danloux, The Flood, 1801. Source: Musée Municipal, Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

The Julie who has briefly but fatally succumbed, in defiance of her father’s wishes, to her passion for her tutor Saint-Preux, has spent her remaining life in a full filial obedience so great that it resembles contrition. Married to Wolmar, the older man her tyrannical father had chosen, having borne children, she has created about her an ordered circle of intimates that includes her former lover. At the moment of her death, though still in her twenties, she is no waif, but a rather imperious woman whose monitory remarks from her deathbed go on for many pages. She looks upon her accident, which decisively prevents her from falling sway once more to her enduring passion for Saint-Preux, as a happy one, upon death as a boon. Her death speech announces that her passage from life is a sublimation for her survivors, as she affirms her will to “rectification,” to the beautification of her life as a story. “My return to God settles my soul and calms me in a painful moment…. Happy I was, and am still, and happy I will be … (Nouvelle Héloϊse, 714–15). Although she will be massively mourned, we are invited to regard Julie’s death as an ethical as well as an aesthetic good. Her children having passed beyond infancy, they are at an age when they will be removed from her authority so as to continue their education as men. Julie herself avers that her continued life would be useless to her, for having known all the bliss of passion and of domesticity she was capable of feeling, how could she find further profit from staying alive? The way she expresses this reinforces the notion that female life is disposable after sexual and reproductive use. “When once one has obtained everything, one can only lose, even if it is only that the pleasure of possession weakens with use” (714).

Two powerfully emotion-laden scenes of the novel are crucial to our theme. Saint-Preux’s account of the storm on the lake in which the little company is capsized during an otherwise peaceful excursion, develops the association of passion with engúlfment. “Any moment, I thought I would see the boat capsized, this touching beauty struggling amidst the waves, and the paleness of death drawing the roses from her cheeks” (499). The beloved, principle of light and purity though she is given us as being, has a killing affinity with the swirling waters.12 Tormented by the impulse to redeclare his passion for her, Saint-Preux, in a mimesis of sexual desire, writes of his violent longing to throw her into the waters so as to “end his long torment in her arms” (504); but as he realizes that her own passion for him is passing through a similar trial, both become subdued. A mutual awareness of sexual passion becalms the lovers, stills their desire.

Figure 11.9 Jacques Gamelin, The Flood, 1779. Source: L’Eglise Saint-Vincent, Carcassonne.

Tanner has also stressed another premonitory scene of disaster in Rousseau’s fiction, that of the dream of the veil. Saint-Preux dreams of Julie’s mother on her deathbed, Julie weeping disconsolately beside her. The mother turning toward Julie, says, “You will be a mother in your turn,” and disappears. Saint-Preux dreams on. “In her stead I saw Julie … ; I recognized her although her face was covered with a veil. I gave a shriek and rushed to put the veil aside; I could not reach it. I stretched out my arms and tormented myself, but I touched nothing.

Figure 11.10 Jean-Baptiste Regnault, The Flood, 1789. Source: The Louvre, Paris.

“‘My friend, be calm,’ she said to me in a low voice. The terrible veil covers me. No hand can set it aside’” (603).

Maternity casts its fell veil over desire. Putting these two scenes side by side, we may distinguish what Tanner has referred to as “the problematical relationship (or opposition) between the dissolving liquefactions of passion and the binding structurations of marriage” (172). These are, at the core, the terms of the conflict we witness in all our other exempla of engulfed women: they play out the lover’s unwillingness to confront the female object of desire at those moments when she ceases to be one, and his insistence upon her watery mutability and mortality in evasion of an awareness of her essential unsinkability.

Tanner in fact notices what he terms “a perverse element” in Saint Preux’s failure, as he watches her floundering in the lake, to think of saving Julie. The drowning scene, as well as Julie’s eventual death by water, convey the ambiguity of engulfment by passion. Praised by all for her goodness and purity, the beloved, by her consent to her demise—clearly a species of sacrifice—takes upon herself the task of disculpating sexuality itself of guilt or consequences. By washing them away, cleansing them in the waves, she will allow the hero’s passion—for herself remembered, or for another—to be reborn after her death.Rousseau’s image of that fateful veil of motherhood comes as an antithesis to the passionate freedom of the open waters of desire. The dream condemns woman, Julie, to extinction for her indelible association with giving birth, in consecration of an ancient pattern of male anxiety.13 In Rousseau’s novel, both their conceded aptitude for passion and their biological maternity predestine women for early mortality. Drawing men, through passion, into a domesticity that spells passion’s end, the persons of women are in Rousseau a site of conflict redeemable only through sentimentality. The goodness of Julie, her crown, has a leaden weight.

Julie, of all people, becomes the spokesperson for male sensuality as she tries to convince Saint-Preux to marry: “Man was not made for celibacy, and it is quite unlikely that a state so contrary to nature should not bring with it some disorder, whether public or concealed. How then to escape the enemy we carry always with us?” (656). This framing of male desire as a fractious enemy within fits the picture of the novel as a whole, in which passion, infinitely alluring, has absolutely to be transcended, for it splinters the vision of what the hero longs for even more than union: freedom from conflict, freedom for the free-ranging, desiring male subject.

For we see that despite verbalizations of fealty to domestic order, the orderliness of Clarens, the Wolmar’s estate, arises far less from its dubious marital bliss than from a dream of an agricultural community that acts as a cornucopia to an intimate society of friends, among whom dangerous passionate impulses “safely” pass to and fro. This underlying layer of the work is far more consonant with Rousseau’s professed views than with his fictional structures. We see these views openly displayed in the scolding he administers women in a footnote, in which he chides them for wishing to make men aspire to fidelity; that is, for him, fixity: “You are certainly mad, you women, to want to give consistency to so frivolous and fleeting a feeling as love. Everything in nature changes, everything is in continual flux, and you want to inspire constant passion! By what right do you claim to be loved today because you were yesterday! Keep the same face, the same age, the same temper, be always the same, and then you’ll be loved if possible. But to change ceaselessly and wish still to be loved is to want at every moment to cease being loved; it’s not to seek a constant heart, but a heart as changeable as you are yourself” (403).

This overt statement interfaces with the novel to imply that what is at stake in the symbolic image and fate of Julie is a restructuring of male passion and that of its female object that, while casting the beloved as a fount of good and—at least here—allowing her her own capacity for passion, nonetheless kills her off in her youth so that she may never grow beyond her ability to inspire it. In this system, male passion is less expressed in the male self than in his female other who plays out the ravages of his self-doubts, guilts, and loyalties. The representations of the engulfed beloved mirror men’s desire. Yet they convey an idea of “woman” to women also, nonetheless and inevitably. Such a vision excludes maturity or power from female self-representation, no less than from male representation: reproving women’s self-assertion, it tends to encamp them in self-concepts of juvenility and pathos.14

Nancy Miller has alluded to the eighteenth century novel’s obsession with threatened female innocence and speculates, I believe accurately, that it may be a “working out of an unsaid male ambivalence on the part of male writers toward the very existence of female desire, and an unsayable anxiety over its power” (134). Rousseau very nearly exposes the core of a related hostile male response to the lack of innocence in women in Saint-Preux’s remarks on the manners of city-bred women. Interestingly, he ties their verbal freedom to their sexual predatoriness: both repel him. Woman’s sociability is itself a threat to confident, unstressful male dominance.

As Saint-Preux writes to Julie, in comparing the Parisiennes unfavorably with herself, “that charming modesty that so distinguishes, honors and embellishes your sex, seemed to them rough and loutish … no decent man would not lower his eyes before their self-assured glances. In this way they cease to be women; out of the dread of being identified with other women, they prefer their rank to their sex and imitate prostitutes so as not to be imitated” (245). Their speech he finds even more revolting. “It’s even worse when they open their mouths. What comes out of them is nothing like the sweet and coaxing voices of you Vaudois women; it’s a sort of harsh, bitter, interrogative, imperious, mocking tone, stronger than a man’s” (246).

This text richly sets out Rousseau’s own reaction, which he apparently assumed would be widely shared—and was certainly not widely contested—to the assumption of power in a mixed society by the women of the upper classes and their inevitable imitators as influence brokers and as vocal members of society with unrepressed eyes. That mixed society itself is a deliberate target of Rousseau’s, as he strongly advocates precisely the social separation of the sexes and the concentration of their activities into the separate spheres the revolution eventually enacted. Beneath the overtly misogynous polemic, we perceive Saint-Preux’s malaise in approaching such verbal and assertive women as the Parisiennes as objects of desire. Too characterized, too distinct, too critical, they are too much at ease in public; so much so that he characterizes them as public women. For Rousseau such women obstruct his creation of fantasy based upon his construction of their gender, thereby blasting his persistent longing for effortless fusion.15

One might propose that the moralized art of the revolutionary era, in its images of dead and dying women, reflects a sort of cleaned-up version of rococo eroticism, where unformed heroines in the flower of youth die amidst settings of storm or flood instead of inviting swift moments of sexual congress on clouds and in wooded bowers. What distinguishes the new mode, however, is that it prefers sublimation to embraces. As Tanner remarks of Saint-Preux, his onanism is the mark of his impotence (122). We are moving toward that mal du siècle that afflicts the Werthers and Renés with their loss of moral and sexual nerve. The French novel that most spectacularly exhibits that loss of nerve while pitting the older, cynical gender dispensation against the new sentimental one, is Laclos’s Liaisons dangereuses (1782).16

For the worthless allegiance of the libertine Valmont a titanic struggle is waged between the wicked, manipulative, controlling, self-conscious Marquise de Merteuil and the good, dutiful, artless, manipulable Madame de Tourvel. The potent power of verbal seduction as art, as deployed in the letters of this work, reveal it as a locus of pent-up passions. Laclos is quite explicit: the Marquise has ironized and internalized the male libertine’s code. In her famous Letter #81, she tells us how experience has taught her to despise spontaneity, which makes so easy a mark of so many women: her law is that of a secret mastery over circumstances, a secret necessarily, since her relentless code, even for her corrosive set, is an unseemly one for a woman. Although devoid of all sense of solidarity with women, Merteuil yet views herself as a female avenger of male tyranny. Emblematic of the woman of society (Seylaz, 89), the Marquise as phantasm reflects the terror of women as sexual predators, manipulators of men’s desire. Although the novel reveals an identical mechanistic manipulativeness in Valmont, for readers of eighteenth century novels hardened to male seduction, his shock value is simply not comparable to our amazement at Merteuil.

The contrast between the two women is what makes the novel take on the aspect of a war: but the war is not really between them; rather it is a contest to see which model of woman will form a couple with the man. Madame Riccoboni and her friends saw the work as a war against their kind, the women of society. A popular novelist, Riccoboni wrote Laclos protesting at the way he had made the Marquise use her cultivated arts to serve evil ends. She also assailed him for his lack of patriotism in what she saw as his slandering of French woman by his creation of Merteuil, a personage, she claimed, resembling no one she herself had ever, in her long experience, met up with (Laclos, O. c. 713). Laclos was immovable. While admitting there were few Merteuils, he insisted there were some (714–15). The reality quotient scarcely mattered. His novelistic character would remain as a cautionary figure to women of the fate of the ruthless cultured woman. Placed on the scale with the sacrificed, unworldly “natural” woman Tourvel, her arts cannot save her from flying off into oblivion, being shunned by society, exiled to Holland, and marked by the pox of her diseased spirit. She does not even have the grace to die.

Within its terrified rejection of the woman of power as the culprit for the sexual/social system, the Liaisons dangereuses exhibits its disarray, still mixed with male complacency, before cynical sexual plunder. Exhaustion with heartlessness finds expression in the meek, gentle figure of the innocent Tourvel, whose very name suggests the tender turtledove. The greater the pain in the surrender of the beloved, the greater the joy of the lover’s conquest. Forced to feel, he thinks he loves. In arms like Tourvel’s, a man might find—himself.

Sade’s heroes too exhibit what Michel Camus has termed their “monosexuality” (267) in their obliteration of the object. But whereas Rousseau had sought to repress women’s “culturedness” as he celebrated their bonds with nature, what Sade longs to destroy in them above all is precisely their putative “naturalness,” their maternity, that very state wherein the age’s dominant consensus decreed their redemptive potential must lie.17 Jean Ehrard has written that in the late eighteenth century the concept of Nature eclipses even that of Divinity and moves from being a mere order to becoming a full-fledged power (in Camus, 273). Insofar as that sacred power was represented by the female figure—certainly it was so for the revolution until 1794—it would nonetheless end up by being felt to be “out of order” in its threat to patriarchal preeminence. The remedy Sade proposes to this trend toward celebration of the feminine lies in a system of female self-abasement exemplified in his cartoon character Justine’s demands upon others to punish and debase her relentlessly. As her final speech argues, she has always been magically in order, submissive and ready to die: “this unhappy creature who had imbibed only snake’s venom, whose unsteady feet have trod only upon nettles…; whom cruel reverses have robbed of family, friends, fortune, protection and help…; such a one, I say, sees death come without fear; she even welcomes it as a secure port where tranquillity may be reborn for her in the bosom of a God too good to allow innocence vilified on earth not to find a reward in the other world for having suffered so many evils” (143–44). Sexual use by her tormentors simply confirms Justine’s status as the sacred object of nature, therefore demanding defilement. Her fantasized ironic acquiescence to her fate, even to her death, confirms the mythic locus of power as resting with those torturers. But Sade does not refuse himself, in this work, a “sentimental” resolution in which Justine does not actually die. (Since she is not really sacred, her sacrifice would be pointless.) The revolution is under way as this work, whose tongue-in-cheek contradictions are reworkings of the underlying sexual code, is being written.

Bernardin de Saint-Pierre’s Paul et Virginie (1788) constitutes a sort of exact inversion of Sade’s Justine in its gender politics: paradoxically, chastity no less than sexual use or abuse destroys young women. Its mythical and allegorical vagueness is what lent the work its unbelievable (to latter times) success: for it met with an absolute frenzy of enthusiasm in the prerevolutionary public, apparently responding to an ever more potent need for moral renewal, a renewal that would take the emblematic form of investment in the sacrifice of her life by a young and untried woman. No stereotype of female goodness has been left out of her composition. Bernardin’s Virginie feeds the birds; like Cunégonde and the children of the old man at the end of Candide who make sherbets and sweets, she prepares cakes for the poor. With her frère de lait Paul, she listens avidly as her mother reads the Gospels. The shorthand depiction of Paul makes him frank, open, cordial: his soul-sister’s nature is confiding, “tenderly caressing” (252). Consenting to leave their little matriarchal family’s idyllic but primitive existence in Ile-de-France only so as to redress its fortunes, Virginie voyages to wicked France. Ignorant and trusting, she will be cruelly deceived by the rapacity and heartlessness of her great-aunt: she rejects the loveless match proposed for her, is disinherited, and summarily placed aboard a ship back to her island home during the hurricane season. The grandiose and/or ludicrous apogee of her life is her apotheosis as she dies in the stormy seas. Refusing to remove her clothing to plunge into the waters and be saved, she raises her serene eyes on high “like an angel who takes flight heavenward” (345).

As the phenomenal popularity of the work confirms, the description of Virginie as she prepares to leave her Caribbean home incorporates into her moral and physical attributes the topos of the young woman as chaste ideal of this time. “She was dressed in white muslin over pink taffeta. Her tall, lithe figure was perfectly visible beneath her stays, and her blond hair, braided in a double tress, admirably adorned her head. Her beautiful eyes were filled with melancholy; and her heart, agitated by contained passions, gave her complexion an animated flush and her voice an emotional pitch. The very contrast with her elegant adornments, which she seemed to be wearing in spite of herself, made her languor the more touching. No one could see or hear her and remain unmoved” (285–86). Virginity and goodness, yes: but under siege by nascent passion from within and without. Obsessed by the imperative of making of herself a gift—to the birds as to the poor—she offers the paradigm of the young woman as consumable object, in her unconscious narcissism and sensuality offering herself, while yet withholding appetite, her own or others,—at some remove; inviting desire, but only on pain, as we discover, of that death by drowning which finally allows the sensual languor of the girl’s body to untense itself and release the hold of chastity’s imperative.

Martyrdom is crowned in this heightened version of the paradox of female chastity by the propagandistic sanctification of Virginie that follows: “Mothers asked God for a daughter like her; young men for a mistress as constant; the poor for a friend as tender; slaves for a mistress so good” (352). The text drives home the prescriptive quality of her example for her sex as the poor young girls she had helped have to be restrained from throwing themselves en masse upon the coffin of “their sole benefactress” (353).

A compact prurience in Bernadin’s prose couples budding sexuality with the pains of ignorance: his attribution to Virginie’s person, in his description, of the sexual power that flows toward her, makes her an ambiguous victim: and indeed, Sade apart, in none of these literary works is the beloved less powerful than her lover, since the charge of passion is seen to be emitted by her. But in fact, such felt power is precisely what appears to be in need of control—by works of art that enact its nullification, making both men and women sense the futility of women’s powers and, conversely, the utility of a model of female powerlessness to making the sexes feel a mutual attraction to each other. Sweet and innocent, the young woman struggling against the flood wrests love from the reader. The consequent acceptance of pity as the precondition for sexual passion implies the internalization, the ratification by men of a pattern of regarding women, as Rousseau had preferred to, as weak objects, hence sexually approachable; it implies for women an acceptance of themselves as needing to repress all appearance of strength so as to appear pitiable, hence desirable, approachable. This posture would then become an imprisoning precondition of their own sexual and social responses.

No author was more obsessed with the figure of the engulfed beloved than the greatest poet of the revolution, the one deriving his inspiration most directly from Greco-Roman antiquity, André Chénier. Guillotined as a moderate by the Terror in 1794 at the age of thirty-two, Chénier wrote a quantity of his finely wrought neoclassical verse in prison at Saint-Lazare where he spent the months before his execution. A remarkable medium for the taste of time, two of his poems bring him especially within our purview. Both La Jeune Tarentine and La Jeune Captive, works tirelessly anthologized, are celebrations of a young beauty facing death. The Young Tarentine met with immediate and eager readerly acceptance. It describes a young bride in all the splendor of her nuptial adornments as she sets out by boat to join her lover. But alone in the prow of the ship, the “impetuous wind” catches up her veils and she falls into the waves and dies. The goddess Thetis protects her body from the monsters and the Nereids carry her to the shore. The young poet’s voice laments, Alas! she was never to return to her lover; never to wear her bridal dress. The mourning for her untapped sensuality can be heard as the poet alludes to the “gentle perfumes [that] never flowed through your hair” (11–12). Chénier recaptures the poetic lament for the dead bride from antiquity and hands it on to Romanticism. A recurrent theme with a resilient life, it spoke again to the revolutionary generation. The poet’s other enormously anthologized work, a song of praise to an imprisoned young woman, The Young Captive, is a modern poem rather than a neoclassical one, which owed much of its popularity to the pathos of the Terror. Significantly, its main stanzas are spoken by the young woman herself, who compares her person to an ear of corn ripening in the summer sun, trusting not to be cut down before her time. Despite the pains of the present day, she clings to the beauty of existence, asking that she not die. “I am only in the springtime, I want to see the harvest,” she tells death, pleading that it wait and let her live out her love.

The Young Tarentine simply evokes with the greatest economy the figure of the dead bride, clothing it in none of the overlay of moralism or sentimentality that shrouds Bernardin’s Virginie. No moral burden of goodness is imposed upon her: simply, she is doomed before she can know life to the full. But her figure retains and reinforces the familiar aura of that girl most beloved of men, since so much sublime male poetry is devoted to her, who has never reached the nuptial bed, whom male desire has reached out for, but never touched. As to the Young Captive, unlike Rousseau’s Julie who, though allowed to speak, makes deathbed reflections full of self-denial, Chénier not only has her speak her own lines, but defend her right to live (185–86). And she is not made, in the poem, actually to die. Unlike Julie or Virginie, she is not constrained by the poet to accept death as an epiphany. All the epiphanies of this poem are in its life lines.

The Young Captive is the single significant work of art on the theme of the dying woman that, albeit in the ambiguous tones of the popular pathos, gives expression to the revolution’s own moment of aspiration for women from 1789 to 1793 by letting the captive speak as her own advocate. This moment is the one historically recorded in women’s cahiers de doleance and in their political and street activities.18 We ought not be surprised that it should have come from the pen of a Feuillant and a constitutionalist, for whom a speaking woman claiming her right to life was not an outrage.

Chénier’s heroines have been read retrospectively as allegorically loaded emblems of the abortive French Republic, without history or roots or future. Such a political reading is plausible enough; but it remains significant, on the most overt level, that such expressions of dismay should be expressed so often by male artists via the alterity of woman, and specifically through her death before her sexuality and her maturity have flowered. When we read these works solely as allegory, we neatly efface from consciousness their brute force as gender constructs, as ideological prescripts.

Restif de la Bretonne’s work lies in a journalistic gray area between gossip and the imaginary. In 1797 he published among his Nuits de Paris a curious account of an incident—whether actual or apocryphal we are always in doubt with Restif, so we may think of it as a construction. “At Fontenay-le-Peuple,” it begins, “there was a watchmaker named Filon, who had a very beautiful wife. Two emigres returning from England had seen her and their greatest desire was to possess her.” They went to Filon’s house and found her there with her husband. “Her beauty, her gentleness disarmed them; that is, they could not do violence to her before her husband as they had planned to do” (273). So they tell her her life is in danger and they’ve come to take her off to a safe place to protect her. But once she’s in their house, they violate her, after tossing a coin to see who would begin. “They satiated themselves at length. After which, remembering how much they had desired her and how pretty she was, they were about to kill her out of a kind of jealousy when another thought came to them; it was to degrade her so that they might feel no regrets over her.” So they proceed to have her raped by their valets as they watch, and then by their coachmen. They then take her home, dying; but she doesn’t die. After taking leave of her senses for two months, hiding herself under beds and in the cellar, and trying to jump into a well, she is cured by being sent to a quiet place. Restif ends his story, “You can see her still, in Paris.”

In this unsublimated account of male desire, class resentment is overwhelming: the returning aristos, thinking that everything belongs to them, have appropriated whatever falls beneath their gaze that promises to gratify their senses. They enact the ruthless sexual violence associated with the ancien régime. Yet even though Restif may tell this story to cast opprobrium on the aristocracy, certain elements of our pathetic fictional sexual fable that transcend class considerations are curiously recapitulated here: the legendary beauty, the actual goodness of the unnamed woman provoke the men’s imperious desire to defile them, in Sadean fashion; with satiety comes this moment of “jealousy”: She cannot be allowed to survive their desire, to be desired by others of their class, by men of lower class, or even by themselves. Is this “jealousy”? Or is it revulsion against their own desire that they turn against the one who has evoked it? In a sense, Restif’s fable strips bare the mechanism of this reduction of the woman to her moment as an object of use that we find sublimated in the poeticized dying beloved. Here, for her attackers, being used (passed around), and by men of all classes, is equated with being used up. Once passion is spent, she is ready for consignment to the trash heap. Consignment to the watery deep is not so different from this fate. But in this version, though scarred, she survives. The reader is reassured by this ending, implying that rape, though dramatic, is but transitory. Male passion may be vicious at times, it suggests, but not lethal.

Transposed anew to the poetic level, we find the issue of woman as a figment of male fantasy explored by the conservative Chateaubriand in his 1801 tale, Atala, intended to take its place in his magnum opus, Le Génie du Christianisme, but so popular after its first printing that it was republished five times in that same year. Already in 1791 as he set out on his six-month voyage in America, as Chateaubriand would later tell us in his Mémoires d’outre tombe, the heroine of his novel dominated him. “Having attached myself to no woman, my Sylph still obsessed my imagination. I made it my happiness to traverse with her the forests of the New World” (Garnier, xxvi).

A verse makes waggish summary of Atala’s fate.

Ci-git la chrétienne Atala

Qui, pour garder son pucelage,

Très moralement préféra

Le suicide au manage

Or roughly,

Here Atala the Christian lies

Who chose a virgin to remain

And chastely gave herself to pain

Of death instead of marriage ties.

Chactas, now a blind old Natchez Indian, recounts her tale to the young French traveler René. In his youth, Chactas had come under the protection of a Spaniard, Lopez, who had educated him as a son and a European. Nostalgic for his native forests, Chactas leaves him to return to his people: but he finds that his tribe has been defeated by the Muscogulges (or Creek) tribe, who, taking Chactas prisoner, sentence him to death. Atala, a Christian and daughter of the enemy tribe’s chieftain, pities the captive. They fall in love, she liberates him, and they flee by night. Yet Atala, though deeply enamored of Chactas, refuses to let herself love. At the height of a storm, she confesses to her lover that she is Lopez’s daughter; she and Chactas, finding themselves children of the same father, are then overpowered by passion, and she is close to succumbing to her desire—for it is hers that is dwelt upon—when a missionary, Pére Aubry, discovers them and offers them shelter in his grotto. Aubry makes Chactas visit his mission so as to display to him the virtuous orderliness of the savages who have converted to Christianity. But when the two return to the grotto, they find Atala dying: sworn by her devout but ignorant mother to a life of virginity and feeling herself, in her passion for Chactas, helplessly about to betray this vow, she has chosen suicide, not realizing that such a course is a sinful one for Christians or that a bishop might have delivered her from her parent’s ill-considered pledge. She agonizes through the night, dies, and is buried at dawn by the sage and her lover, as shown in Girodet’s celebrated painting from the Salon of 1808 (Figure 11.11).

Figure 11.11 Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson, The Funeral of Atala, 1808. Source: The Louvre, Paris.

As Julie dominates Saint-Preux by her personality and character, even as Virginie does Paul, so does Atala outshine Chactas. Her courage saves him from death, her determination carries them safely through the forests. Her very conflict over her passion makes her more substantial than her passive lover. Despite this manifest vitality, Chactas reflects to René about the cloud that cast its shadow over even the lovers’ very first kiss: “Alas, dear son, sorrow follows closely upon pleasure” (Delmas, 47). This lugubrious mood of Liebestod is sustained as Atala and Chactas visit the tomb of a child whose grieving mother addresses her dead little one: “Happy are those who die in the cradle! For they have known only the kisses and smiles of their mother” (Delmas, 49).

Yet Chateaubriand’s emotionally effusive funeral dirge can also sound a note, in the context of tribal war and nationalism, of open contempt for women. Chactas taunts his Muscogulge captors: “I do not fear your torments…. I defy you; I scorn you more than women” (Delmas, 54). In this way, Chateaubriand’s text, an emanation of the Napoleonic era, declares openly what other sentimental fiction had striven to repress or at least not to betray: a singular male ambivalence toward even the beloved, devoted, and sacrificial, but impassioned, woman. Atala is torn, palpitates with desire; but her lability of sentiment is a decidedly mitigated good:19 “Atala’s perpetual conflict between love and her religion, the abandon of her love and the chastity of her habits, the pride of her character and her deep sensibility … everything together made her an incomprehensible being for me. Atala could not have a feeble power over a man: full of passion, she was full of power; one could only adore or detest her” (Delmas, 59). We note Chateaubriand’s candor: Atala’s active desire is what dooms her. Such a woman is better adored dead.

In his retrospective dismay at having lost her, Chactas describes what might have been his fate and gives us a clue as to why their love was ill-fated: “A mudhut with Atala would have brought me such happiness; there all my races would have been run; there with a wife, unknown to men, hiding my joy deep in the forests, I would have passed on my way as do the rivers that, in the wilderness, have no name” (Delmas, 74). In this telling version of married felicity, union with Atala is equated with subordination to her desire. Chactas’s personhood would be lost to him: no more struggle, no experience except the quotidian, no name. This vision of man reclaimed by nature dissipates precisely what revolution and romanticism promised men: freedom of the imagination guaranteed by a sense of their power as individuals. Here consent to a woman’s passion is the emblem of its dispersion and loss.

Atala’s incipient flaw of having imposed the heat of her desire upon her lover is punished in the much admired delectatio morosa of her funeral scene. Every single element in it bespeaks chastisement, from the partly unclad bosom and the faded magnolia—the flower that Chactas had cast upon her bed to make her fruitful—to her ebony crucifix. The “celestial” vision is one of sleeping virginity (Delmas, 91). “The morbid sensuality with which Chateaubriand portrays the cadaver of his heroine shows what pleasure he finds in imagining the beloved woman dead,” writes Lehtonen, one of his critics (95).

That this morbid obsession is not Chateaubriand’s alone must now be clear. Denis de Rougemont, who has written somewhat disaffectedly about the nexus of love and death in literature, opines that on the individual level “the passion of love is at bottom narcissism, the lover’s self-magnification, far more than it is a relation with the beloved” (270). One would have to argue, in the light of our survey, rather that passion has some need, fortunately not always exercised, to obliterate the object. De Rougemont stresses the notion that male sexuality in western culture tends to reassert itself according to the old formulations of redemption: “the more passionate a man is, the more likely he is to revert to tropes of the rhetoric, to rediscover their necessity, and to shape himself spontaneously according to the notion of the ‘sublime’ which these tropes have indelibly impressed upon us” (176). Hence Chateaubriand’s, Chénier’s, Bernardin’s, and Rousseau’s ready deployment, in their magnifications of the male lover’s passion, of the ancient and ever renewable category of the “sublime” to deal with the encounter with woman. At the same time, there is something new and modern about the insistence upon these tropes in this specific era of human history, the age of raised bourgeois awareness of a universal human nature and condition. In his interrogation of this very idea of sublimity, Theweleit has seen it as a “(historically relatively recent) form of the oppression of women through exaltation, through a lifting of boundaries, an ‘irrealisation’ and reduction to principle—the principle of flowing, of distance, of vague, endless enticement” (284). In other words, the image of the sublime engulfed beloved swindles woman out of a sense of her own power and out of inclusion in universal personhood.

This confrontation of works during a forty-year span featuring the prostrate or dying woman reveals a persistent male anxiety around the issues of masculinity as dominance and of sexual fidelity during the time of gestation of the modern republic. Both of these preoccupations implied a need to police women’s behavior. What currents had fed this male anxiety over the emergence of women as individuals? We may make some guesses. Anguish over the loss of human ties as witnessed in the tide of infant mortality and abandonments as rural life began its long disintegration, perhaps. Almost certainly a related uncertainty about paternity, which would produce the obsession with chastity and the great bourgeois return to paternal prerogatives. Yoked with the age-old misogynies of the combined Christian and Gallic traditions, a sullen jealousy of the confident women of high society for what was felt to be their usurpation of power and influence would play its own incalculable role. And perhaps a longing for a less brutalized model of sexuality in which their desire would not be experienced as a fractious enemy, an agent of disorder, might have contributed to men’s refashioning of love and family life. In any case, the wresting of sexual order out of its chaos seemed to most of them to demand the redomestication of women and their departure from the public space. Most of this program is inherent in polemics and works of art that precede 1789, as we have seen.

Women’s eruption into historical action in events like the October Days of 1789, as they formed a boisterous crowd to march on Versailles and bring the monarchs triumphantly back to Paris, in the light of the underlying gender tensions, could only reinforce a reaction of terrified consternation among the most male supremacist of the men. Women’s own modest demands for change by the revolution at first met with some success, to be set aside later as militarism came to dominate national life. As the claims of women were swept aside, first Jacobin and then Napoleonic politics would finally embody those lovingly fashioned, seductive visions of sacrificial female goodness in their legislation. The long evolution from monarchical society’s dominant conceptualization of woman as man’s lively and energetic opposite, even when defeated or despised, had given way to the new paradigm: the feeble subordinate.20 Who can say whether the political revolution, among the eddies of its turbulence, was not also a struggle to assure this end?

In subduing female self-affirmation, romantic culture wove other elements into its skein. The male artists of romanticism would appropriate their conception of the female principle in their own tendency to swoon with the very sensibility with which they endowed their heroines, outdoing them in “their” presumed game of dolorous sentiment and love of love.21 Finally, the long emotional tide of male resentment adumbrated in the figures of the engulfed beloved effects a sublimation, etherealization, and sentimentalization by an influential artistic coterie of what would be given as “natural” sexual impulse. Popular fantasies, elegies of lament for the disappeared object will continue to shroud underlying sexual realities, making male sexual violence and betrayal, actualities of many women’s experience, impossible to avow. By making allusions to such brute realities appear as solecisms against what attracted the sexes to each other, crude invasions of the sacred precinct of what Tanner has termed “the dissolving liquefactions of passion,” this structurally coercive mode of fantasizing sexuality passed itself off as the life-force itself.

Such an alluring phantasm, so easily internalized, enabled the dominant masculinist factions to silence dispute or negotiation over sexuality among or between women and men. With this mechanism in place, the long sleep of pious sexual repression had begun. In the politics of gender, art is not on the margins: it is the arena. The arts, in their gentle, insidious way, had colluded in a “restoration” of their own, a counterrevolution of daunting consequences for humankind.

To call upon Klaus Theweleit’s terms, the male desire that flowed through these images of women had the effect of stilling women’s own expression of desire. Yet art has power to make a naked display even of such repression. Anaçs, the heroine of Grétry’s 1797 opera, Anacréon chez Polycrate,22 speaks the required words of contrition. We may envisage her as the swooning, lightly clad, distraught figure of one of our paintings:

Enamored by a rash passion, I dared to dispose of myself in despite of the rights of my father. I have much deserved his anger. If he must avenge himself, let him punish me alone. I abandon myself to his wrath, for I owe him my life. Let him take it back, then, and forgive me … Fille rebelle, et criminelle—a daughter rebellious and guilty, I ask only to die.

Works Cited

Applewhite, Harriet B., and Darline G. Levy, “Women, War and Democracy in Paris, 1789–94.” French Women and the Age of Enlightenment. Samia I. Spencer, ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

Aury, Dominique. “La Révolte de Madame de Merteuil,” in Les Cahiers de la pléiade. 1951.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books, 1972.

Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, Jacques-Henri, Paul et Virginie. Ed. Jacques van den Heuvel. Paris: Poche, 1974.

Bryson, Norman. Vision and Painting: The Logic of the Gaze. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983.

Cabanis, Pierre-Jean-Georges. Oeuvres philosphiques. Eds. Claude Lehec and Jean Cazeneuve. Paris: PUF, 1956. 2 vols.

Camus, Michel. “L’lmpasse mystique du libertin.” In Sade: Ecrire la crise. Colloque de Cerisy, 1981. Paris: Pierre Belfond, 1983.

Cerati, Marie. Le Club des Citoyennes républicaines révolutionnaires. Paris: Editions sociales, 1966.

Chateaubriand, Fran$ois-René de. Atala-Rene. Paris: Delmas, 1956, and Atala-René, ed. Letessier. Paris: Gamier, 1962.

Coicy, Madame de. Les femmes comme il convient de les voir. London, Paris: 1785.

Chénier, André. Oeuvres complètes. Ed. G. Walter. Paris: Pléiade, 1958.

De Lauretis, Teresa. Alice Doesn’t. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

Diderot, Denis. Oeuvres complétes. Paris: Club français du livre. 15 vois., 1969–73. VI, “Salons.”

Duhet, Paule-Marie. Les Femmes de la Révolution. Paris: Julliard “Archives,” 1971.

Duncan, Carol. “Fallen Fathers: Images of Authority in Pre-Revolutionary French Art.” Art History IV (1981):186–202. See also “Happy Mothers and Other New Ideas in French Art.” Art Bulletin (1973):570–83.

Feucher d’Artaize, le Chevalier. Réflexions d’un jeune homme. London, Paris: 1786. Lettre à Mme Gacon-Dufour, auteur du mémoire pour le sexe féminin contre le sexe masculin. Paris: 1788.

Flandrin, Jean-Louis, “Contraception, mariage et relations amoureuses dans l’Occident chrétien.” Annales XXIV (1969): 1370–90, and Les amours paysannes. Paris: Gallimard, 1975.

Godineau, Dominique. Citoyennes tricoteuses. Aix-en-Provence: Alines, 1988.

Gutwirth, Madelyn. “The Representation of Women in the Revolutionary Period: The Goddess of Reason and the Queen of the Night.” Proceedings—Consortium on Revolutionary Europe, 1983. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985, pp. 224–41; “Laclos and ‘le Sexe’: the Rack of Ambivalence.” Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century 189 (1980):247–96; and “Woman as Mediatrix: From Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Germaine de Staёl.” In Woman as Mediatrix—Essays on Nineteenth Century Women Writers. Ed. Avriel H. Goldberger. New York: Greenwood Press, 1987.

Horney, Karen. “The Dread of Women.” International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 13 (1932):348–60.

Hunt, Lynn. “Engraving the Republic—Prints and Propaganda in the French Revolution,” History Today. October 1980:11–17; “The Political Psychology of Revolutionary Caricatures.” In French Caricature and the French Revolution. Wight Art Gallery, University of California: 1988; and Politics, Culture and Class in the French Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Jordanova, Ludmilla. "Naturalizing the Family: Literature and the Bio-Medical Sciences in the Late Eighteenth Century,” in Languages of Nature. Ed. L. Jordanova. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1986.

Laclos, Pierre Choderlos de. Oeuvres complétes. Ed. M. Allem. Paris: Pléiade, 1943.

Landes, Joan B. Women and the Public Sphere in the Age of the French Revolution. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988.

Lederer, Wolfgang. The Fear of Women. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968.

Lehtonen, Maija. L’Expression imagée dans Voeuvre de Chateaubriand. Helsinki: Société néophilologique, 1964.

Levy, Darline Gay, Harriet B. Applewhite, and Mary D. Johnson., eds. Women in Revolutionary Paris, 1789–1795. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979.

May, Gita. “Rousseau’s ‘Antifeminism’ Reconsidered.” In French Women and the Age of Enlightenment. Ed. Samia I. Spencer. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979.

Miller, Nancy. The Heroine’s Text—Readings in the French and English Novel, 1722–1782. New York: Columbia University Press, 1980.

Neumann, Erich. The Great Mother. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974.

Renouvier, Jules. Histoire de l’art pendant la Révolution. Paris, 1860.

Restif de la Bretonne, Nicolas-Edmé. Les Nuits de Paris. Paris: Hachette, 1960, and Les Gynographes. The Hague, 1977.

Rougement, Denis de. Love in the Western World. Trans. Montgomery Belgion. New York: Doubleday, 1957.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse. Paris: Garnier, 1960.

Rosa, Annette. Citoyennes—Les Femmes et la Révolution française. Paris: Messidor, 1988.

Sade, Donatien, marquis de. Justine ou les malheurs de la vertu. Paris: Soleil Noir, 1950.

Shorter, Edward. “Illegitimacy, sexual revolution and social change in Modern Europe.” In The Family in History. New York: Harper Torch Books, 1973.

Starobinski, Jean. Jean-Jacques Rousseau—La Transparence et I’obstacle. Paris: Plon, 1958.

Sussman, George D. Selling Mother’s Milk: The Wet-Nursing Business in France 1715–1914. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982.

Tanner, Tony. Adultery in the Novel. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979.

Theweleit, Klaus. Male Fantasies. Vol. I. Woman, Floods, Bodies, History. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Trahard, Pierre. La Sensibilité revolutionnaire 1789–1794. Paris: Boivin, 1936.

Vital, Anthony Paul. “Lord Byron’s Embarrassment: Poesy and the Feminine,” Bulletin for Research in the Humanities 86 (1983–85):269–290.

Vovelle, Michel. “Le Tournant des Mentalités en France 1750–1789: La Sensibilité Pre-Révolutionnaire,” Social History 5 (1977):605–629.