The Sun Shines on Nelson

When the French Revolution began with the storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, much of British public opinion was in favour of it, as tending towards a constitutional monarchy like they enjoyed themselves. This began to turn to horror as the government passed into more extreme hands, and European opinion was shocked when King Louis XIV was executed by guillotine in January 1793, to be followed by his queen Marie Antoinette later in the year. British opinion remained divided over the revolution, with Tom Paine and the radicals demanding a more democratic system while Edmund Burke wrote forcefully about the dangers of radical change. The government of William Pitt the Younger knew which side it was on and began to mobilise the fleet to join a conservative alliance that already included Austria, Prussia, Sardinia and Spain. Britain declared war on 1 February 1793. The French were already victorious on land as their ragged but enthusiastic armies defeated the more formal forces of reaction. At sea the position was very different. They still had a very powerful fleet and a great deal of selfconfidence after holding the British off in the last war, but many of the officers were aristocrats who were executed, imprisoned or went into exile. Naval command needed far more technical skill than army leadership, and hastily promoted petty officers, merchant ship captains and politically-motivated landsmen did not fill the gap, either individually or as a group.

One person who was delighted with the new war was Horatio Nelson. Finally released from his domestic boredom at Burnham Thorpe, he was appointed to the twelve-year old 64-gun ship Agamemnon, his first ship of the line. Some would have despised such a command, it was written not long afterwards, ‘…our naval officers either pray or swear against being appointed to serve on board them’ – for a 64, with only 24-pounders on its lower deck, was likely to find itself up against a 74 or even a three decker in a line of battle. But Nelson saw it differently and wrote to his wife after a meeting with the First Lord, ‘After clouds comes sunshine. The Admiralty so smile upon me, that really I am as much surprised as when they frowned.’ He went back to his old stomping ground of Chatham to fit out the ship, which he regarded as ‘without exception, the finest 64 in the service, and has the character of sailing most remarkably well.’1

The Mediterranean Fleet

Nelson did not know it yet, but he was to serve in the Mediterranean Fleet now fitting out at Spithead, to be commanded by his erstwhile friend and patron Lord Hood. Victory was to be the flagship, perhaps because Hood had formed an attachment to it during his previous service, or possibly because it was now considered the most fitting ship for such a command. Victory had been overtaken as the largest ship in the navy by that time, by the new Royal George launched in 1788 and the Queen Charlotte of 1789. That ship was to serve as flagship of the Channel Fleet, the most important one, under Lord Howe while the Royal George was to fly the flag of Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Hood, the brother of Lord Hood, in the same fleet. This left the Victory for the next most important role, as flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet.

Captain Knight described the laborious tasks of fitting out in some detail. Early in the process, on the last day of 1792, ‘PM, received on board gunner’s and boatswain’s stores.’ There was no time to celebrate the newyear and next morning, ‘Employed getting the standing rigging out of the storehouse and bringing it alongside. Came on board 100 men from the Duke and the marines from headquarters.’ In the afternoon, ‘Received on board two months provisions for 200 men of all species, received on board coals and gunner’s stores, employed clearing the lighter of the rigging and rigging the foremast. Riggers on board wolding the main mast.’ On the 3rd they rigged the mainmast and threaded the deadeyes that supported the shrouds, borrowingmen from the Hector and Alfred to help. By the 7th they were ‘swifting out the main rigging and rattling the fore ditto.’ They began to receive anchors and the 9th was spent coilingtheir cables on the orlop deck and stowing the ground tier of casks in the hold. The ship was ready to move out of harbour to Spithead on the 16th and ‘came to with the best bower in 16 fathoms.’2 The ship exercised her guns while at Spithead. She fired off 200 lbs of powder in ‘scaling, priming the 32-and 24-pounders’. Two hundred pounds more were expended firing salutes for the arrival of Sir Hyde Parker and the King’s birthday. On 18 January the 12-pounders were exercised in firing five rounds at a mark, but mostly the gun drill was without firing, as usual, a pattern that continued during the commission.3

The Victory painted by Monamy Swaine in 1793. She still carries Hood’s flag on the foremast and Eddystone Lighthouse off Plymouthcan be seen in the background. The ship’s name is painted on the stern.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, BHC3696)

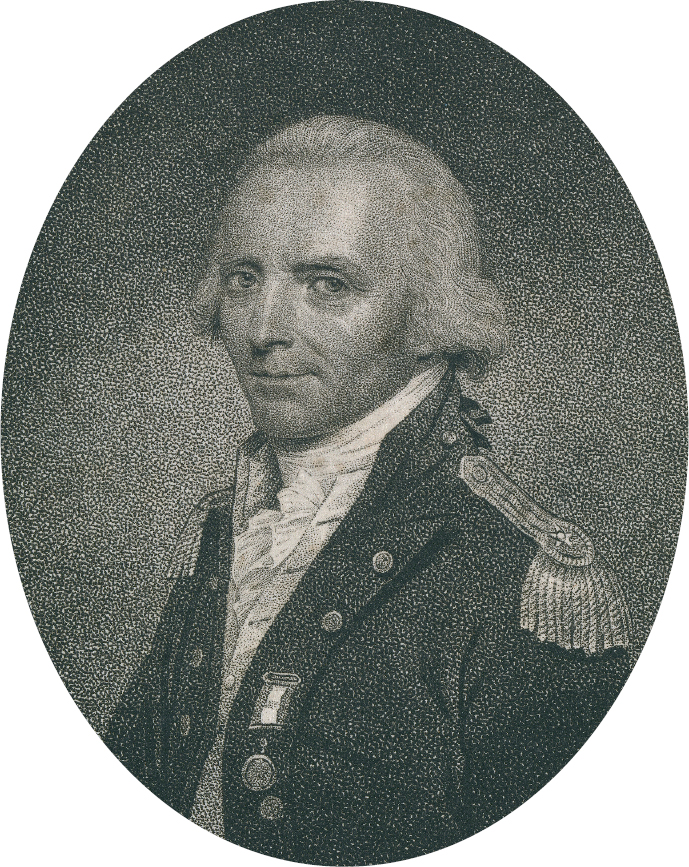

Captain John Knight. Although his command of the Victory in 1793–96 was not considered successful by Jervis, he later earned a reputation as a surveyor and chart-maker.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, L4379)

Midshipman Jeffrey Raigersfield had already experienced bullying in the frigate Pearl and the 74-gun Courageaux. He described this to Captain Knight of the Victory, who had been his captain in the Triumph, and was offered a place in the flagship. But the oppression followed him, at first the other midshipmen would not admit him to their mess. He reported this to the first lieutenant and captain, who assembled the officers and midshipmen on the quarterdeck, to ask them collectively and individually, ‘Whether or not any of them knew any thing [sic] in my conduct inconsistent with the character of a gentleman.’ There was silence, except that one master’s mate mentioned an unsubstantiated rumour that he owed money to inns ashore. The midshipmen had to admit him to the starboard mess but he was still ostracised. However he found a niche, which Nelson would have approved of:

Being fond of boat duty, I was always well dressed by eight o’clock in the morning in uniform and ready, while others, whose turn it was to go in boats, were not so, and I frequently presented myselfand took their turn. This disinterested conduct soon brought me under the notice of the lieutenants, and as I was found to be so good a boatman, and often came offto Spithead, when blowing very hard, and got safe on board when no other boat of the fleet would even leave the shore.

Lord Hood came on board on 7 May and the crews saluted him with three cheers, which was cheaper than gun salutes. Raigersfield described his arrival on board. ‘The fleet was ready for sea, and orders had been given to prepare for the reception of the Commander-in-Chief: the day was fixed for his coming on board, and all officers were expected to be in full dress to receive him. He came alongside and upon deck, the band playing “See, the conquering hero comes!”’ The young midshipman was delighted when his old acquaintance with the admiral was renewed. ‘As he passed on the quarter deck into the cabin, it so happened that I was the only midshipman or person he took any notice of.’ This restored his prestige in the gunroom, for a time at least.4

Hood’s Captain of the Fleet was John Inglefield. William Hotham, nephew of the second-in-command of the fleet, was appointed seventh lieutenant of the Victory in January 1794 and found him to be, ‘a remarkably handsome man, very good-natured and kind in his manners, but without the polish of a man accustomed to much good society.’ He never quite recovered from the loss of the 74-gun Centaur in 1782. The Flag Captain was John Knight, a ‘remarkably quick and active officer, but who ‘was not too popular in the service, and was supposed to pay too much attention to domestic affairs during his service, and to have considered the ship he commanded more a house in which he was residing with his family [rather] than a ship of the British Fleet.’5

Hood’s orders included the three main tasks of a British commander-in-chief in the Mediterranean. He was to protect trade, assembling convoys and using his frigates to escort them. He was to link up with actual or potential allies, which in this case seemed comparatively easy with the almost universal hostility to the French revolutionaries, and that the ambassadors to Spain, Portugal, Naples and Sardinia had instructions to negotiate ‘a concert between [His Majesty]… as to the most effectual means to be taken against the common enemy’. Thirdly, he was to neutralise the French fleet at Toulon, either by blockading it or ‘attempting some decisive blow against the naval power of France.’6

The Admiralty had resolved to send up the fleet in sections escorting convoys, and the Victory left Spithead on 23 May with a group of six more ships of the line and eleven smaller warships, protecting a convoy of East Indiamen. A few days later they passed close to Cape St Vincent in the south-west corner of Portugal, where Raigersfield could see ‘the good fat friars sitting outside their convent… enjoying the agreeable freshness of the North-West wind, which soon wafted us by them, and to Gibraltar…’7 Meanwhile, Nelson’s Agamemnon was one of the ships sent into Cadiz for supplies, as Spain was an ally for once. He observed the condition of their navy as being one of ‘…very fine ships, but shockingly manned… I am certain if our six barge crews, who are picked men, had got on board one of their first rates, they would have taken her.’8 This was something to note for the future. His relationship with the commander-in-chief was improving, but still wary. ‘I paid Lord Hood a visit a few days back, and found him very civil: I dare say we shall be good friends again.’9

The fleet spent a week at Gibraltar then nineteen ships of the line sailed for Toulon where they arrived on 20 July. Raigersfield was one of the officers under Lieutenant Edward Cooke of the Victory in a French prize that was sent into the port with a flag of truce to arrange the exchange of prisoners. But, ‘as we came under the high land that forms the western part of the entrance into the deep bay of Toulon roads, a shot was fired at us to bring us to, which we did, and shortly after a couple of gun boats…. came and took possession of us.’ They were held at Fort de Malgue for several days until they were sent back with a packet of papers, but with no real agreement on the exchange.

Toulon

By the beginning of August, Hood was ‘thinking the Toulon fleet will not come out for the present’ and he decided to ‘show the flag off Genoa’. On the 23rd he received commissioners from Marseilles who wanted to restore the monarchy in their province. Soon afterwards he was joined by a delegation of royalists from Toulon, who offered to deliver the great port up to the Allies. Hood was reluctant at first, he had no force of ground troops to defend the place, but he made a momentous decision, which would indeed be a ‘decisive blow against the naval power of France’. ‘I came to the resolution of landing 1,500 men, and take possession of the forts which command the ships in the Road.’ He was aware of the risks, that ‘in all enterprises of war danger more or less is to be expected and must be submitted to…’ but it was worth it. He was ‘impressed with the great importance of taking possession of Toulon, the great fort of Malgue and others on the main, in shortening the war, I fully relied that in case my endeavour should not succeed, I should be justified in running some risque, being conscious I acted to the best of my judgement as a faithful servant to my king and country.10 On the 28th he issued a proclamation from the Victory. He would ‘take possession of Toulon and hold it in trust only for Louis XVII until peace shall be re-established in France…’11 Lieutenant Cooke of the Victory was sent on shore again and apparently offered to pay the French crews in silver rather than paper. Troops from the various British ships, serving as marines, were rowed over to the 74-gun Robust and the master of the Victory watched them land at 11am. However, Toulon was far from secure, most of the ships of the line in the harbour supported the republic, but the appearance of the Spanish fleet strengthened the allied hand. The Victory herself sailed into Toulon roads at 11 am on the 29th and anchored in seven fathoms of water. On the 30th she shifted her berth to a position half a mile east of Fort Eguelette, with her anchor in ten fathoms, as the position on shore was consolidated. The main post, Fort La Malgue, was given up by the royalists while those defending the town were also taken over. But the whole port had a perimeter of fifteen miles, which would be much harder to defend, especially as Hood had no coherent land force.

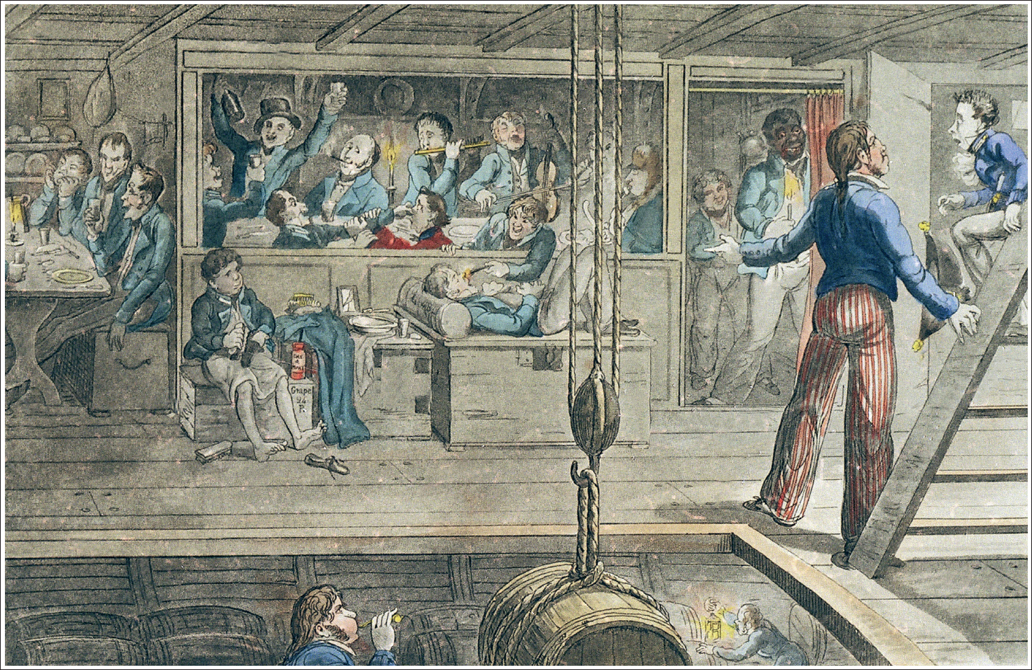

A young man is introduced to the midshipman’s berth, originally drawn by Captain Marryat and prepared for publication by George Cruikshank. The print contains much detail, including the ‘oldsters’ or older masters’ mates etc. to the left; an unhappy midshipman cleaning shoes and another playing pranks outside the cabin, with noisy entertainment inside, and a black servant. In the foreground, a seaman uses a boatswain’s whistle to control the movement of a cask being brought out of the hold while another searches for one in the depths.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PU4722)

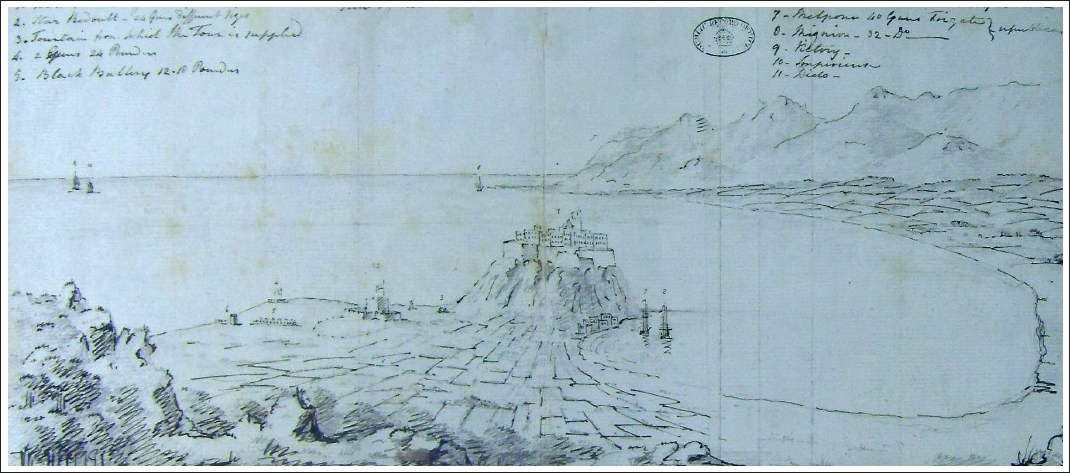

Toulon in Allied possession with forts Balaguier and L’Eguilette in the background. The three-decker in the centre foreground is possibly the Victory.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PAH2315)

Marseilles had been lost to republican forces but Toulon was a prize indeed if it could be held. According to Captain Edward Brenton, who was a poor historian but good recorder of nautical topography, it was ‘the great and only naval arsenal of France in the Mediterranean… a place that has been called one of the finest ports of maritime equipment in the world.’ It had the only dry-docks in the Mediterranean, as they were difficult to use in the tideless sea, but Toulon had a supply of convict labour for pumping and other works:

Besides the inner harbour, which encloses the arsenal [ie dockyard], they have an outer harbour and a road. The inner harbour is a work of art [ie engineering] formed by two jetties… embracing a space large enough to hold thirty ships of the line…. As many frigates, and a proportion of smaller craft, besides their mast pond. The arsenal is on the west side, and the ships in ordinary, or fitting, lie with their sterns or bowsprits or their sterns over the wharf; the storehouses are within fifteen yards of them; the rope-house, sail loft, bake-house, mast-house, ordnance, and other buildings are capacious and good: the model [mould?]-loft is worthy of the attention of strangers.

The town itself, north of the dockyard, was ‘fortified with great art, both on the land and sea approaches’, but it was overlooked by hills which made the position difficult. Nelson was exultant (though he would see little of Toulon as the Agamemnon was mostly employed carrying messages for Hood) remarking, ‘what an event this has been for Lord Hood: such a one as history cannot produce its equal; that the strongest place in Europe, and twenty-two sail of the line, &c., should be given up without firing a shot.’12

One day Midshipman Raigersfield showed some of the tactlessness that perhaps made him so unpopular with his messmates.

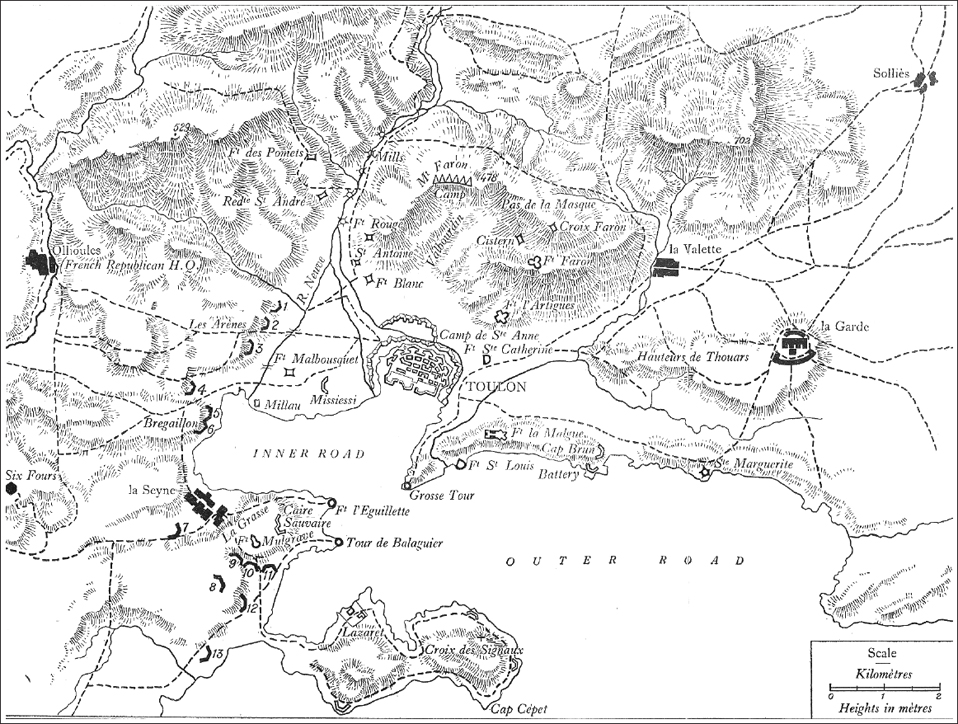

A map of the Toulon campaign showing the town, dockyard and main forts.

(Takenfrom J. Holland Rose, Lord Hood and the Defence of Toulon, Cambridge, 1922, author’s collection)

…Being upon the quarter-deck with several other midshipmen, I thoughtlessly observed it seemed strange to me no preparations had been made for evacuating the place, not that it was now apparent it would be necessary, but in case it should so turn out, as neither the forts nor whatever else in our possession had been mined, or got ready for blowing up… Little did I think at that time that the accidental remarks of a young gentleman in his profession would find their way to the Commander-in Chief’s ears, but they did however, and my promotion was retarded.13

In fact, it was only by a few days, but the young midshipman did not understand Hood’s dilemma. In theory, the alliance against the French revolution was powerful, but the members all had different aims and capabilities. The Spanish greatly resented the British possession of Gibraltar and feared that they wanted another base in the Mediterranean. The French royalists wanted the fleet and base at Toulon kept intact so that they could be handed over to their king as soon as he was restored. The administration in London did not understand the delicacy of the situation and urged Hood to sail the French ships away, or prepare to destroy them and the dockyard as a last resort. On the spot, Hood had a very difficult balancing act.

The End at Toulon

Hood sought allies and especially land forces to secure his possession. Troops were sent from Sardinia and Piedmont and proved effective, those of Spain were less so, while the King of Naples vacillated. Hood’s difficulties were compounded by the long distance from London – it took three weeks to get a message there, and even longer to get a reply. At first he was too optimistic, being ‘confident we can hold what we have got’. Lord Mulgrave, who arrived early in September to take command of the British land forces, was even more sanguine and wrote to Pitt of ‘the confidence I feel of the safety of this place’. Though he had taken measures to burn the dockyard in the event of a retreat, these were ‘vague and I think improbable suppositions.’ This allowed the government to send troops to the West Indies rather than Toulon, while they had contradictory policies on sending men from Gibraltar. But by the time these decisions were being made, the situation had deteriorated. Hood deployed seamen ashore, including some from the Victory, but their style of gunnery was not suitable for land warfare, and in addition it meant depleting his crews.

Things got far worse on 16 September, when a young captain – soon to be promoted major – arrived to take command of the French artillery. Napoleon Bonaparte, with his supreme tactical skill already in evidence, soon recognised that the key to the situation was the peninsula of La Grasse, which controlled the entrance to the inner road and therefore the town and dockyard. Despite his junior rank, his unique leadership qualities inspired the troops and the attack was conducted with new vigour. He mustered all the guns he could find to fire on the fleet and on the vital position. By the 26th, Hood was reporting, ‘We are kept in perpetual alarms and at very hard duty.’ On 7 October he promoted Cooke of the Victory to the rank of commander and appointed him lieutenant-governor ashore, while manning gunboats with midshipmen and seamen. By 11 November, Hood was reporting from the town of Toulon, ‘Seven thousand men now occupy these outposts. That number will not ensure their safety, if they be vigorously attacked; and in this place I must beg leave to repeat that should we be able to maintain all these posts, it may not prevent the dockyard and arsenal from being bombarded.’

On the morning of 17 December, Fort Mulgrave, on the Grasse peninsula, was attacked and taken, with Bonaparte leading the final assault. Eight men of the Victory’s crew were reported missing, besides four wounded, including Lieutenant Goddard in charge of the party – though unlike the Britannia and Windsor Castle she had no fatal casualties. The position was now untenable and Hood made plans for evacuation. The royalists of Toulon had no illusions about what to expect as the republicans advanced, and many took to boats to join Hood’s ships. Captain Knight wrote in his log, ‘All employed receiving French refugee men, women and children.’ The admiral reported, ‘that every inhabitant was brought off as manifested inclination to come.’ The Victory alone carried 705 soldiers and 370 ‘refugee men, women and children at 2/3rds allowance.’ Purser John McArthur made a brave attempt to list their names in the muster book, but he only issued 40 beds to them.14 Apart from the distress of losing their homes and goods, conditions must have been barely tolerable in a ship designed for a crew of 850 in already cramped conditions, on a week-long voyage towards the island of Elba. But according to Lieutenant Colonel John Moore, who had joined too late with a substantial military force, they made the best of it:

Every part of the ship… was crowded with French people, men and women; they are the principal families of Toulon, who made their escape on board the night of the evacuation. I heard a fiddle and dancing in the ward-room, and was not a little surprised when I was told it was the French dancing out the old year; few of them have anything but the clothes on their backs, and the prospect before them is gloomy, yet they contrive to make themselves happy… Her quarter-deck forms a curious medley. There were French ladies and gentlemen, officers of the navy and army, commissaries &c.15

But Moore said nothing about the condition of the poorer refugees and the soldiers crammed below decks.

Meanwhile Captain Sir Sidney Smith was charged with destroying the ships and dockyard, but it proved harder than imagined. On the 19th, as the Victory left Toulon roads for the last time, Captain Knight ‘observed a great fire, supposed to be the ships and Arsenal.’ It was initially claimed that twenty-seven ships, including seventeen of the line, had been destroyed; but it later emerged that only nine of the line and three others had been put beyond repair.16 Three ships of the line were captured. The 74-gun Pompee proved to be a very fine ship but the Scipion was lost soon afterwards. The huge Commerce de Marseilles of 120 guns helped to inspire a move towards bigger ships that left the Victory behind, though she never served as an active warship in the Royal Navy due to her structural weakness.

To Corsica

The withdrawal was a major setback for Hood and the fleet, but already there was a new target where they might curtail French power and set up a major British base in the region. On 20 November, a small boat had arrived off Toulon from Corsica. The Spanish Admiral Langara was horrified to hear that the islanders had thrown off the French yoke, but Hood was more sympathetic to the rebels for he ‘always understood that a very great part of the inhabitants of Corsica refused to acknowledge themselves subjects of France.’ He knew something of the recent history of the island. It had been under Genoese rule for centuries, until 1755 when Pasquale Paoli led the people in settingup a democratic government, twenty years before the American Revolution. Unable to control the island, the Genoese sold it to France and she used her much greater military resources to crush the democrats at the Battle of Ponte Novu in 1768. Among those who fought on the defeated side was Carlo Bonaparte, who now had to make the agonising decision about whether to accept French rule or go into exile, probably in Britain. He chose the former and as a result his son Napoleon was a French subject when he was born in the following year. The young man was back in the island in 1791, trying unsuccessfully to maintain the rule of the French revolutionaries there

Ships blowing up and burning during the evacuation of Toulon – but in fact the damage was not nearly as serious as this dramatic view suggests.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PY3230)

Paoli did go into exile in Britain where he became a member of the circle of Doctor Johnson and James Boswell. He was a remarkable man, of great intelligence and charm. He was back in Corsica with the revolution, but was soon put offby its extremism and the execution of King Louis XVI. He led a revolt and soon only three fortified towns in the north of the island – Calvi, San Fiorenza and Bastia, were still in French hands. Hood sent Captain Edward Cooke, formerly of the Victory, to the island to make contact. Paoli requested British help and announced ‘the desire of me and my people to put ourselves under the government and protection of His Britannic Majesty and his nation without reserve.’ Hood was well aware of the importance of the island to France, while to Britain it would offer ‘several ports, and that of San Fiorenza a very good one for the reception of His Majesty’s fleet in that part of the Mediterranean.’ He had already sent several ships before the main fleet of sixty ships, including transports, left Hyeres Bay off Toulon on 24 January after receiving Cooke’s report and Paoli’s offer. In this campaign, the roles would be reversed, Nelson would be in the thick of the action while the Victory was on the sidelines.

On the way, as Hood reported, ‘towards daylight it blew very strong, and before ten o’clock quite a storm, which made it prudent for me to bear up for Porto Ferrra [on Elba]’. It got so bad that the pilot declined charge of the ship and they were driven to the leeward of the island where Hood ‘passed three very disagreeable nights having had two main topsails blown to rags, and the topsail yard reduced totally.’17 Although he did not conceal his dislike of Hood and the navy, Lieutenant-Colonel John Moore had to admire his coolness and seamanship on the last of these nights. He and his army colleagues were sleeping in the outer cabin of the admiral’s quarters, opposite the open door of Hood’s cabin. At 1am they were woken by Captain Inglefield, who told them to dress quickly as he feared the ship would run aground. Moore could see that Hood was ‘not the least discomposed’ by the news. The admiral dressed ‘with the greatest deliberation’ and Moore was reassured enough to go back to sleep. On deck, according to Lieutenant Hotham, Captains Inglefield and Knight and the master were ‘all at variance as to what was to be done’ until ‘the calm presence of mind and the professional knowledge of our venerable Commander-in-Chief’ came into play. Hood directed ‘the main sheet to be a little eased off, the bowline checked, and the ship to be kept clean full’ so that she ‘passed by very close and with a heavy press of sail.’18 The ship arrived at Porto Ferraio on the 29th, the refugees were landed and the ships were repaired during the next week.

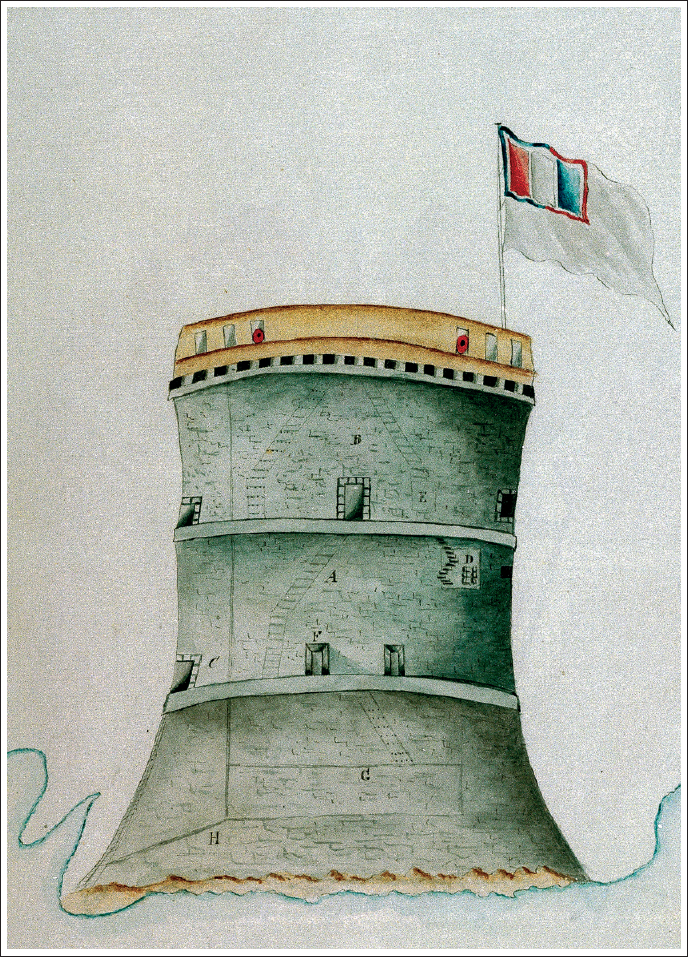

They sailed on 6 February and next day they began disembarking troops under Lieutenant-General Dundas near the tower of Mortella, on the west side of San Fiorenza Bay. Hood noted that ‘the walls of the tower were of a prodigious thickness, and the parapet, where there were two 18-pounder guns, was lined with bass junk five feet from the walls and filled up with sand. The cannonade from the heights above did not make much impression over the following two days while the frigate Fortitude was damaged by red-hot shot. The Victory was never close to the action and on the 11th a strong westerly gale forced her to take shelter under Cape Corse. She was back on the 17th to witness the tower being stormed by soldiers and seamen. Then the tower at Fornalli was attacked and Gilbert Elliot, the prospective British governor of the island, watched as the sailors moved cannon into position over rough terrain. ‘They fastened great straps round the rocks, and then fastened to the straps the largest and most powerful purchase or pulleys and tackle that are used on board a man-of-war. The cannon was placed on a sledge at one end of the tackle, the men walked downhill with the other end of the tackle. The surprise of our friends, the Corsicans, and our enemies, the French, was equal on this occasion.’19 Circular fortifications like this had been out of favour among military engineers since the days of Henry VIII, but this affair made a strong impression on those involved. Meanwhile, the town of San Fiorenza fell as the soldiers defending it retreated eastwards over the hills towards Bastia.

Seamen landing guns from ship’s boats on the coast of Corsica, then hauling them up aslope while soldiers look on.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PAH2355)

The Mortella Tower off St Fiorenze in Corsica. It and the one at Fornells caused their attackers a great deal of trouble, which eventually led the British government to build chains of ‘Martello’ towers on the south and east coasts of England, and in other places throughout the world.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Naval Chronicle)

Bastia

There was no legal mechanism for placing army formations under the command of the navy, or vice versa, so in combined operations everything depended on good relations between the land and sea commanders. This did not happen in Corsica, where Dundas and Moore resented Hood’s arrogance. There was a further complication in that there were several army regiments serving in the place of marines in Hood’s ships, borne as part of the complement, and many of these had been landed to take part in the assaults round San Fiorenza. Soon Dundas and Hood clashed about what to do next. The admiral wanted to attack B astia right away before the French had a chance to augment their fortifications. Dundas considered this to be ‘a visionary and rash attempt’ and wanted to await reinforcements. Hood was sceptical – ‘I do not see there is a prospect of any coming’, he noted. Councils of War on 16 and 20 March only reinforced prejudices, the naval officers voted to attack and the army to wait. Hood decided to press on with the resources at his command despite ‘manifold obstructions, that were industriously thrown in my way.’ The situation did not improve after Dundas was superseded by the even more cautious Brigadier-General D’Aubant.

Nelson had been off Bastia in the Agamemnon since 7 February with several frigates under his command, and he landed several times in the area. He observed the defences on 19 February:

On the town-wall next the sea, about twenty embrasures; to the southward of the town, two guns are mounted on a work newly thrown up, and an officer’s guard encamped there; they are also throwing up a small work commanding a large road to the southward of the town, which leads towards the mountains.’

And, as he noted three days later: ‘I find the enemy every hour are strengthening their works.’20

Hood joined him with the Victory on the 23rd and stayed for two weeks, hoping that a show of force would bring a surrender. After replenishing at San Fiorenza he returned on 4 April to anchor south of the town ready to invest it, with Nelson taking charge of the seamen on shore and Lieutenant-Colonel Vilettes, an officer more in sympathy with Hood’s aims, in command of the soldiers landed from the fleet. D’Aubant grudgingly lent two officers and twenty-five artillerymen, but Hood had wanted double that number. On the 11th, one of the Victory’s boats carried a message to the French commander under a flag of truce, but was told in no uncertain terms, ‘I have hotshot for your ships, and bayonets for your troops.’ Hood had arranged his ships in a crescent off the town, the siege began and it was bombarded by land and sea.

On 15 May, a boat heading for Bastia with gunpowder was captured, and was found to be carrying the mayor’s brother. He was brought on board the Victory where he was treated with ‘great attention and kindness’ by the officers. He expressed his alarm at the possible danger to his family if the town was stormed. John McArthur, Hood’s secretary, cunningly offered him a place on the quarterdeck to watch an attack next morning and told him, ‘nothing could avert the impending horrors, but a flag of truce with proposals from the town.’ The prisoner offered to send a letter stating that there was no hope of relief, but instead Hood agreed to send in the coxswain of the captured boat, ostensibly to get some necessities for the prisoner, but actually to spread news of the impending attack.21 By this time, a stroke of luck meant some army reinforcements had arrived from Gibraltar and were ready to join the fight. On the 19th, Hood ‘received a message that the garrison was desirous of capitulating on honourable terms’ and he sent a note to the shore. ‘This brought on board the Victory three officers, who informed me that Gentili, the commandant, would assemble the officers of the several corps and the municipality if a truce took place, which I agreed to, a little before sunset.’ On the 23rd, the French troops were embarked to be taken to France, while the British took possession of the town, the capital of Corsica.

Now Hood had to deal with another issue, returning the fleet to its more usual role. The French had repaired much of the damage done at Toulon and on 5 June a fleet of seven ships of the line, led by the 120-gun Sans-Culotte, sailed from the port. Hood sailed to intercept them with thirteen of the line, though Colonel Moore complained inaccurately that ‘Lord Hood, on the report of eight sail of the line having got out of Toulon, thinks proper to assemble and cruise with seventeen.’22 The two fleets were in sight of each other by the 10th but Admiral Martin took his ship into the Golfe de St Juan between Antibes and Nice, where he anchored in a tight formation reminiscent of Hood’s own masterly defence at St Kitts twelve years earlier. Hood was desperate to fight a fleet battle as the crowning glory of a naval officer’s career. He made plans for his ships to attack with the Britannia and St George taking on the Sans-Culotte, the Victory and Princess Royal the 80-gun Bonnet-Rouge and so on – but the position was too strong and he had to retreat back to Corsica.

The Victory off Bastia during the campaign against the town

(© National Maritime Museum. Greenwich, London, PAD5982)

Calvi

Meanwhile, at a ‘general consult’ of the Corsican people on 14 June, Gilbert Elliot was proclaimed as viceroy of the island on behalf of King George III. Only Calvi was left in French possession. The town was on a prominent hill on the west side of a large bay and was well fortified, with outlying posts at Monteciesco in the hills southwest of the town, and the Fountain and San Francesco Batteries and Fort Mozello closer in. Nelson arrived in the area on 18 June and began to reconnoitre – the only landing place he could find was Porto Agro to the west of the town, though it was ‘very bad; the rocks break in this weather very far from the shore, and the mountain we have to drag the guns up is so long and steep…’23 The seamen worked to clear roads among the rocks and then began to haul guns up, but Nelson’s 250 men were barely enough to haul a 24-pounder. He wrote to his wife eight days after landing, ‘Dragging cannon up steep mountains, and carrying shot, has been our constant employment.’24

Hood arrived in the Victory after the stalemate at Golfe de St Juan to spend much time cruising offshore, for, as Moore put it bitterly, ‘Lord Hood continues to hover round us eager to have his name in the capitulation.’ The new army commander, General the Hon Charles Stuart, was well-respected by army and navy alike but Hood was suspicious that he was influenced by Moore. He lent men from the Victory to help with hauling the guns and 290, about a third of the complement, were on shore at one time or another. However, he continued to worry about what would happen if the French came out of Toulon and he would have to withdraw them. Guns were eventually set up at Notre Dame de la Serra on the top of the hill and on the right flank the Royal Louis battery, manned by French royalist sailors, opened fire on the hill fort of Monteciesco on 4 July. On the left, guns were lowered down the hill on the other side and the Grand Battery was set up in front of Fort Mozello. On the 12th there was a heavy exchange of gunfire and Nelson was hit by gravel thrown up by a shot. He wrote, ‘I was wounded in the head by stones from the merlon of our battery. My right eye is cut entirely down; but the surgeons flatter me I shall not entirely lose the sight of that eye; at present I can distinguish light from dark, but no object.’ He had lost the sight of the eye permanently, though not the eye itself.

A view from Notre Dame de la Serra looking down over the fortified hill town of Calvi, drawn by an officer on the spot during the siege of 1794. The Victory is offshore, number nine in the picture. Nelson lost the sight of his eye attacking Fort Mozello, seen in the left centre of the picture.

(© National Archives, Kew, Surrey, MPK12/1)

Hood continued to supervise, and he did not always approve of Nelson’s style:

My Dear Nelson,

I thank you for your letter, and desire to have a daily account of how things go on. I would not by any means have you come on board; and do most earnestly entreat you will give no opinion, unless asked, what is right or not right to be done; whatever that may be, keep it to yourself, and be totally silent to every one, except in forwarding proposed operations…

The attack pressed on with Hood urging negotiation with the defenders, which the soldiers refused. Nelson eased the supply problem by finding a way to land stores and ammunition at Vaccaja, on the right side of the hills. There was a truce at the end of July and the French surrendered on 10 August, to be evacuated. Moore complained that Hood and the fleet had ‘forsaken us’ and there were not enough men to dismantle the batteries and remove stores.

After more time blockading Toulon, Hood was worn out and in November he left the station in the Victory. She arrived in Portsmouth on 5 December and Hood struck his flag ten days later. Moore had complained, ‘It is singular under such circumstances Lord Hood should take the Victory home, when he might be conveyed equally well in a frigate.’25 However, it did allow the Victory to be repaired after two years of hard service. She was taken into dock at Portsmouth on 5 January 1795. The yard ‘made-good defects’ in the ship, which must have been considerable as the repair cost more than £13,000 and took three months. Hood fully expected to return as soon as he had rested for the winter, but his frankness was too much for the administration and he had seen his last sea service, at the age of seventy.

Thus the Victory was absent when Nelson saw his first fleet action. The command devolved on Sir William Hotham with his flag in the Britannia. He was an undistinguished and rather unlucky admiral who had been in temporary command at New York when the British army was defeated at Saratoga in 1777, and in charge of the inadequate escort when a rich convoy was captured by the French in 1780. On 12 March he found a French fleet of equal numbers but far inferior crews, and began a chase. Only Nelson in the Agamemnon showed any enterprise, he chased one damaged French ship being towed by another and turned the ship to fire his guns on them occasionally. As a result, the Ça Ira and Censeur were captured, but Nelson was far from satisfied when the pursuit was abandoned. He stormed on board the flagship in an insubordinate rage and Hotham replied, ‘We must be contented, we have done very well.’ Nelson wrote to his wife, ‘Now, had we taken ten sail, and had allowed the eleventh to escape, when it had been possible to have got at her, I could never have called it well done.’ It was a credo for the rest of his life, but for the moment Hotham’s conduct was considered satisfactory and he was honoured for the minor victory.