Taking Stock

At Gibraltar there was time to assess the physical and mental damage to ships and men. Midshipman Rivers counted ninety-two ‘most dangerous’ shot holes on the starboard side, presumably close to the waterline so that they could cause leaks, and forty-two holes to port.1 Midshipman R. F. Roberts reported:

The hull is much damaged by shot in a number of different places, particularly in the wales, strings and spirketting, and some between wind and water, several beams, knees and riders, shot through and broke, the starboard cathead shot away; the rails and timbers of the head and stem cut by shot; several of the ports damaged and port timbers cut off; the channels and chain-plate damaged by shot and the falling of the mizzen mast; the principal part of the bulkheads, half-ports and portsashes thrown overboard in clearing ship for action.2

Rivers noted that the figurehead had a cherub on each side, the starboard one with a blue-painted ribbon representing the seamen and the other a red one for the marines. That one had lost an arm and the blue one a leg, and he noted that among the crew, sailors had mostly lost arms and the marines legs, perhaps because of their positions in the ship.3

Some of the crews were allowed ashore at Gibraltar, and those from ships in the thick of the action, such as William Robinson from the Revenge, regarded themselves as greatly superior to the others:

Some of the crews belonging to the different ships in the fleet would occasionally meet on shore, and one would say to another tauntingly, on enquiring to what ship he belonged; ‘Oh! you belong to one of the ships that did not come up till the battle was nearly over;’ and others would be heard to say, ‘Oh! you belong to one of the Boxing Twelves, come and have some black strap and Malaga wine,’ at the same time giving them a hearty shake by the hand. This was signifying that the heat of the battle was borne by the twelve ships which had first engaged and broke the line.4

Clarkson Stanfield’s painting shows the Victory, largely dismasted, being towed towards Gibraltar after the battle.

(© National Maritime Museum. Greenwich, London, PAH8042)

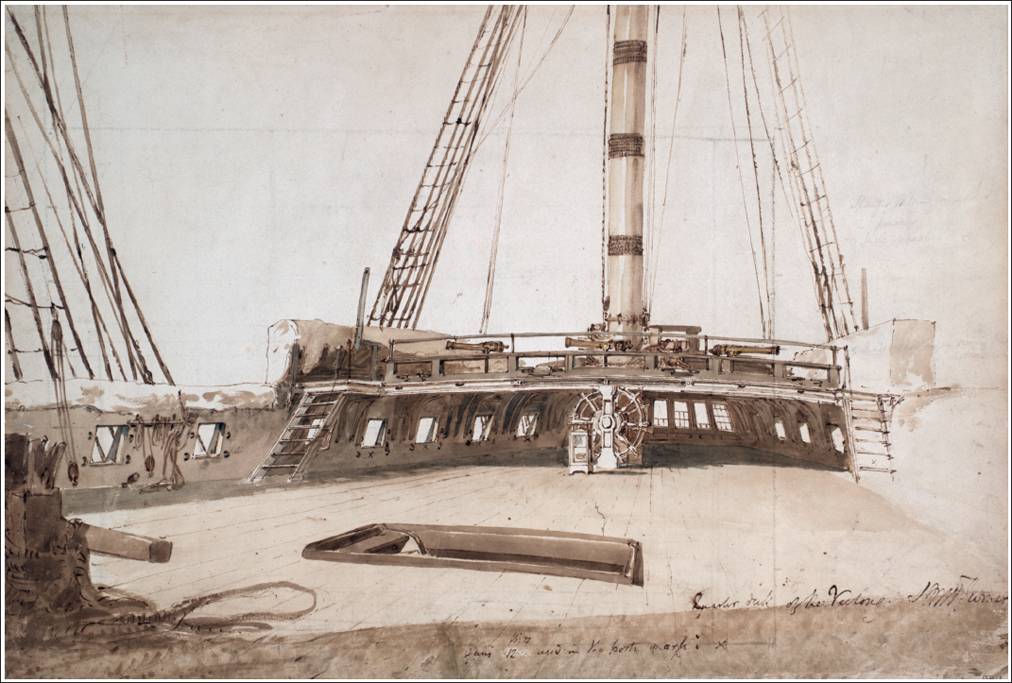

The ship had been superficially repaired by the time J.M.W Turner saw her in the Thames Estuary on the way to Chatham.

(© The Tate Gallery, London, D08183)

No doubt the Victory’s men were high among this elite band, but many of them were suffering from what we might call post-traumatic stress and Lieutenant Yule wrote to his wife:

…The horrors of an action during the time it lasts and or a short time afterwards makes everything around you appear in a different shape to what it did before… The action will be by the nation conceived as a glorious one but when the devastation is considered how can we glory in it? How many orphans and fatherless has it made?… the loss of our chief has thrown a gloom around that nothing but the society of family and friends can dispel. That quarter-deck which was formerly crowded is emptied. The happy scenes we formerly witness are now laid aside, the theatre, the music, the dancing which accompanied the dull part of our time is laid aside. We look to the seat of an old messmate and find he is gone – we ask for such and such a man – he was killed, sir, in the action, he lost a leg.5

Lewis Roteley described what happened to Nelson’s corpse after the action:

To preserve the body a large cask called a leaguer was procured and lashed on its end to the middle deck. The body was brought up from the cockpit by two men which I received from [them] and placed it head foremost in the cask. The head of the cask was then replaced and filled with brandy and a marine sentinel placed over it by night or day so that it was impossible for anyone to approach it unseen. It remained in this state for several days when one of these sentinels came to me in great consternation and said there was something the matter with the cask. I went to the spot and found the head of the cask heaving and raised up ready to burst. A gimlet was procured and vent given and all was right. There had been an escape of air from the body which had caused this phenomenon, alarmed the sentinel and I suppose gave rise to the report of ‘Tapping the Admiral’.6

This view of the quarterdeck is more finished than most of the sketches Turner made on board the Victory. It shows the decks largely deprived of guns, apart from a pair of very light ones on the poop. The captain’s cabin in the stern is stripped out, as it would have been in action.

(© The Tate Gallery, London, D08725)

Repairs were carried out, including a jury-fore topmast and a spare anchor was found in the dockyard. The Victory set sail on 4 November and entered the English Channel on 1 December, to be saluted by the naval ships she passed. She arrived in the Solent on the 4th and anchored at St Helens at 2pm, with Nelson’s flag flying at half mast, while all the ships at Spithead lowered their flags in the same way. She was visited by the artist Arthur Devis who made sketches for a painting of the death of Nelson. Due to the damaged state of the ship, it was feared that the body might have to be unloaded and taken across country, but more emergency repairs were carried out and she proceeded on the 10th. She anchored off Dover and was seen by Thomas Pattenden, who observed, ‘yesterday and today the Victory with the corps[e] of Lord Nelson on board came to anchor off the harbour. The wind was strong from the north and north-west which prevented her going round the North Foreland.’7 Nelson’s body was taken out of the cask and put into a plain elm coffin under a canopy of colours. The Victory arrived off the Nore on the 22nd, where the ships at anchor lowered their colours, but it was the 23rd before the weather moderated and the body could be transferred to the Chatham yacht for the voyage up river to Greenwich. The great artist JMW Turner arrived on board at this point and set about to fill several notebooks showing details of the ship and some of the crew, as well as a larger drawing of the quarterdeck. Having said her last farewell to Nelson, the Victory went to Chatham for much-needed repairs.8

The Funeral

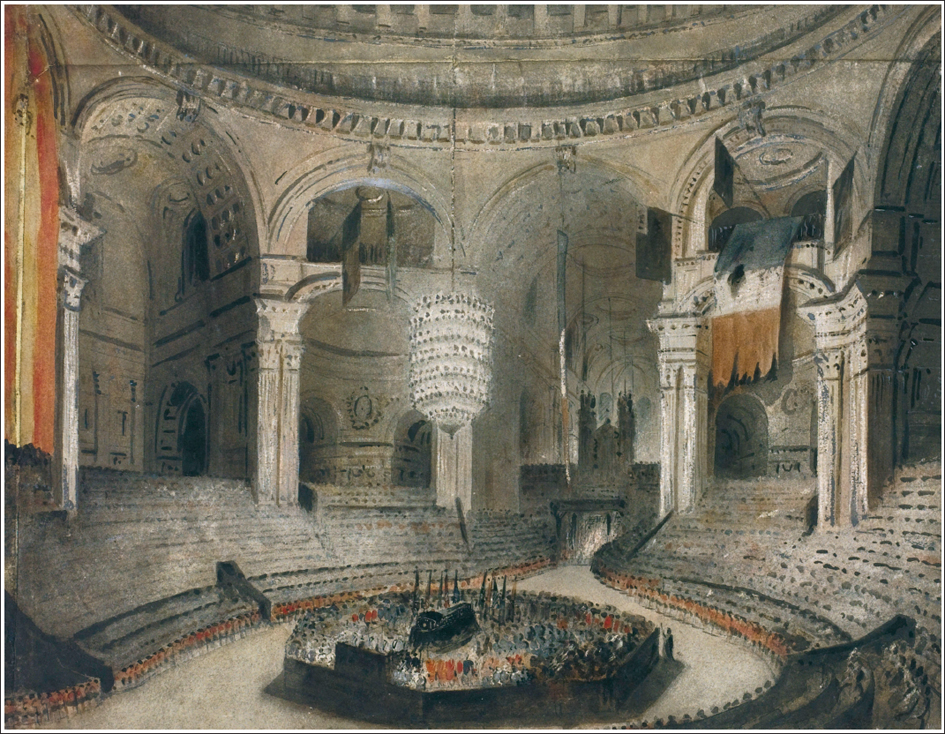

Nelson’s funeral was planned as a national event on 8 January 1806, perhaps the grandest non-Royal funeral ever staged in the country. The body was to lie in state in the Royal Naval Hospital at Greenwich, and Chaplain Scott, being ‘stupid with grief’, lodged nearby to watch over it. After that, it was taken up the Thames in a procession watched by vast crowds, in a barge which also carried Lieutenants Pasco and Yule and the Master Thomas Atkinson. Forty-three seaman and a dozen marines were to represent the Victory at the funeral, presumably chosen because they were least likely to desert or be seduced by the pleasures of the capital city after nearly three years at sea. Seventeen of them were petty officers, including Master-At-Arms Henry Ford, and the miserable Benjamin Stevenson. Eighteen more were experienced able seamen, with only five ordinary seamen and three landsmen. The marine party was headed by Sergeant James Secker who had carried Nelson’s body below, and he was assisted by Corporal William Cogswell.9

Nelson’s funeral. The scene inside St Paul’s Cathedral with captured flags hung from the arches. The marines and seamen of the Victory are in the central area as the coffin is lowered into the grave.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PAH7331)

The seamen marched as part of a great procession through London, ‘two and two, in their ordinary dress, with black silk handkerchiefs and stockings, and crape in their hats.’ The body reached St Paul’s Cathedral in the afternoon, with twelve of the Victory’s men carrying it on their shoulders while the others bore the battle-damaged colours from the flagship. Then, according to the official report in the London Gazette:

The Comptroller, Treasurer and Steward of His Lordship’s household then broke their staves, and gave the pieces to the Garter, who threw them into the grave, in which the flags of the Victory furled up by the sailors, were deposited. – These brave fellows, however, desirous of retaining some memorials of their great and favourite Commander, had torn off a considerable part of the largest flag, of which most of them retained a portion.10

Many portions of the flag can be found in museums today, and still appear occasionally at auction. And the selection of reliable seamen was not entirely successful – Able Seaman William Martin, Ordinary Seaman George Prescott and Landsman Thomas Matthews did indeed ‘run’ from the group.

Repaired Again

The Admiralty ordered Chatham Dockyard to survey the Victory as soon as she arrived, and on Boxing Day 1805 they reported optimistically that she would have to be docked and would require five or six weeks work. Able Seaman Brown wrote, ‘we scarce[ly] have room to move the ship, so full of nobility coming down from London to see the ship so full of shot holes.’11 The ship was given a certain amount of priority among all the other repairs, but by 11th January it was not clear whether she would be ready to dock by the next spring tide. Delays continued, but on 27 February the Chatham officers reported that she would at last be docked, while her crew would be distributed ‘to greater advantage.’ In fact, most of them went to the new second rate Ocean, including Benjamin Stevenson who was no happier when he wrote to his family from the ship on 4 July. But somehow he was reconciled to naval service, he was appointed boatswain of the brig Halcyon in 1809 and had made £273 in prize money by 1812.

The Victory finally re-entered her birthplace, Number Two Dock, on 6 March. It did not take long to discover that “the copper for the time it has been on is much worn’ and needed to be replaced. It was no longer intended to put her back in service immediately and in April plans were made for airing and drying her in the ordinary. She was finally ready for undocking on 3 May. The dockyard officials continued to examine her and in October they reported that the drying and airing had proved beneficial and that she was now ‘in a state to be brought forward for service.’ By March 1807, it was planned to dock her again, but on 11 April the tides were ‘so very slack’ that it had to be postponed for a fortnight and she entered Number Two Dock yet again on the 23rd to have her copper re-nailed during a short stay.12

One of several existing fragments of the Victory’s flag, authenticated by its weave.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, AAA0924)

The Victory’s headlong charge into battle highlighted one of the great weaknesses of the current form of construction – the structure of the bow was very weak above the level of the upper deck. Robert Seppings had already noticed this in his capacity as Master Shipwright at Chatham. When he cut down the Namur from a three to a two-decker in 1804, he got permission to leave the original bow structure intact. He wanted to build up the bows in other ships, but doubted if the conservative Navy Board would support him. He described his reaction when the Victory arrived for repair:

…It appeared that this ship had suffered very severely on the main deck, when in the act of bearing down on the enemy, in consequence of having only a flimsy beak-head, instead of continuing the regular built circular form to the upper part of the forecastle; for it was evident, that even the common grape shot had penetrated the birthing of the beak-head, when shot of the largest size had not made their way through the circular and regular built bow below.

He ‘communicated to Captain Sir Thomas Hardy, who commanded her, what I had done in cutting down the Namur, and Sir Thomas was equally anxious for the change with myself; but all innovations are attended with difficulties and I could not get it generally adopted until the year 1811.’13

In November 1807, the Admiralty ordered the Victory to be made ready for sea ‘with all possible dispatch’, but the optimism about the state of her hull had dissipated. It was proposed to remove the internal structure of riders to air the planks and the Chatham officers wanted to put her into dock again to make it easier to move heavy materials. She was ‘somewhat hogged’ after long years of service. She was docked on the 18th and at the end of the month it was reported that, ‘we find her to have received very considerable injury from the rapid progress of the dry-rot.’ Although she had benefitted from the airing and the vegetation which caused the rot had been destroyed, it had ‘made great progress’ in the internal planking before the remedy was applied. The officers, including Master Shipwright Robert Seppings, were highly critical of the policy of sending the ship to sea so soon after her great repair – ‘…between four and five years since, the repair of this ship for the hull only cost the sum of £46,157 and many thousands expended since…’ They were convinced that ‘commissioning her immediately as she is launched or after receiving a great repair’ was what did the damage. They recommended the ancient policy of ‘snail creeping – defined by James Ballingal in 1832 as ‘cutting small scores or channels on the faying [ie joining] surfaces of the timbers and planks’.14 She was ready to undock by the end of December.15

On 11 November 1807, the ageing ship was reduced to the second-rate, which in practice meant a reduction in guns, rig and crew numbers. As early as April 1806 her gun armament had been under consideration, and the officials were not enthusiastic about the nonregulation 68-pounder carronades. Instead, they proposed a more conventional combination on the quarterdeck and forecastle – long 12-pounders ‘in the wake of the rigging’, where the blast of a carronade might set the shrouds on fire, and 32-pounder carronades in other places so that the forecastle would have one carronade and long-gun per side, and the quarterdeck would had two long-guns and eight carronades. The reduction to a second-rate also meant that the 24-pounders of the middle deck were replaced.16 In March 1808 the Victory was listed as carrying twenty-eight 32-pounders on the lower deck, thirty 18-pounders on the middle deck and thirty 12-pounders on the upper deck. The quarterdeck and forecastle had six 12-pounders and ten 32-pounder carronades.17

New and smaller masts were made at Deptford, although there was much confusion over dimensions. It was found that the mainmast was too short and it was proposed to add twelve inches to its foot. At first, the foremast was thought to be ten inches too long, but it was soon discovered to be three feet short and Chatham recommended using a standard mast from a 74-gun ship rather than adding a piece to the bottom. The officers asked if new sails were to be made, or the old ones cut down, and eventually it was agreed that new ones would be made under contract as the yard sailmakers were busy.18

The Baltic

Many of Nelson’s sailors believed that their victory at Trafalgar would end the war and allow them to go home, but they were severely disappointed. Yet again, Britain was victorious at sea while France was supreme on land, with Napoleon’s destruction of the Austrian armies at Ulm and Austerlitz in October and December 1805. Prime Minister William Pitt reportedly said, ‘roll up that map; it will not be wanted these ten years.’19 Pitt died in January 1806 and there was no-one of sufficient stature to fill his place. But neither side in the war intended to give way, Napoleon instituted his Continental System to ruin the trade of what he called a ‘nation of shopkeepers.’ By the Berlin and Milan Decrees he forbade the ports of Europe to trade with Britain, while the British retaliated by banning any port which enforced the decrees from trading at all, hopefully sending frigates and sloops to enforce this. The Royal Navy had to expand to cope with this, from 569 ships in 1805 to 673 in 1810.

Map of the Baltic, showing the major powers in the region – Denmark-Norway, Sweden, Prussia and Russia, which included Finland.

(Taken from SR Gardiner, A School Altlas of English History, London 1902)

British trade with the Baltic had increased tenfold since the wars began in 1793, largely because it was an entrance for manufactured goods and colonial produce to northern Europe, while most of the south was under French control or occupation. Furthermore, it was a vital source of naval stores. As well as iron ore from Sweden, the region supplied Russian mast timber, oak for planking and fir for decks of both naval and merchant ships. Most important of all, ninety percent of hemp used for rope-making came from Russia and attempts to grow it elsewhere had failed. It was essential to keep the sea open to trade despite Napoleon’s attempts to seal it off.

Nelson’s battle off Copenhagen in 1801 had been settled almost amicably by negotiation, but in 1807 the Royal Navy carried out a far more brutal and devastating attack on the city, though the Danes had done nothing more than maintain their independence and their fleet. This time, troops were landed and the city was shelled, causing much damage. The report of 2,000 civilian casualties was probably greatly exaggerated but it caused huge and lasting bitterness from the Danes, who now became a firm ally of France – though without their battlefleet which had been captured or destroyed by the British. Meanwhile, the Russians, forced into an unlikely alliance with the French, were conquering Finland from Britain’s last remaining ally, Sweden. This was the complex and volatile situation which a commander-in-chief on the Baltic would be faced with. It has never been established whether the Admiralty’s choice for the post was a product of great insight and prescience, or just fortuitous.

Vice-Admiral Sir James Saumarez was a Guernsey man whose uncle had served with distinction alongside Keppel in Anson’s circumnavigation of 1740–44, but was killed in action three years later. Young James had a rapid rise and was captain of the 74-gun Russell at the Battle of the Saintes in 1782, when he showed great initiative, as he did at St Vincent fifteen years later. Two years older than Nelson, he served as senior captain under him in the Nile campaign of 1798 but was never under his spell. Nominally, he was second-incommand but Nelson never really recognised that and preferred to work through his friend Thomas Troubridge. Historians have made much of Saumarez’s confession to his wife that, ‘did the chief responsibility rest with me, I fear it would be more than my too irritable nerves would bear.’ – but the Nile campaign was an exceptionally stressful one, which arguably damaged Nelson’s mental health for some years afterwards. In the morning after the battle he had the temerity to criticise Nelson’s organisation, to the admiral’s annoyance. In July 1801 Saumarez was a rear-admiral and led an attack on a French squadron in Algeciras Bay near Gibraltar. HMS Hannibal was driven ashore and lost, but Saumarez retreated to Gibraltar and refitted his ships in record time. The French had now been reinforced by Spanish ships but Saumarez captured one French ship and destroyed three Spaniards.

Edwin Williams’ later portrait of Sir James Saumarez shows him with a rather arrogant pose and expression, though actually he was noted for his modesty and humility.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, BHC3010)

Saurarez was as religious as Nelson, but had a very happy marriage in which his wife Martha was his main confidante. He was deeply honest and highly sensitive about his honour, though largely indifferent to money, unlike many officers. He seemed aloof at first, but did not inflict his religion on others and was popular with officers and men. His bilingual upbringing in Guernsey perhaps gave him a flair for languages, and an understanding of other cultures which Nelson, for one, lacked. On 20 February 1808, Lord Mulgrave, First Lord of the Admiralty, wrote to him offering a fleet of twelve or thirteen ships of the line for ‘the important service of attempting to destroy the Russian fleet and of affording protection to His Majesty’s firm and faithful ally, the King of Sweden.’ He was to have the assistance of two very able rear-admirals, Sir Samuel Hood, a cousin of his namesake who had flown his flag from the Victory fifteen years before, and Richard Keats, who knew the area well. Saumarez wrote back that he could not ‘for a moment hesitate’ to accept such a responsible role.20

Saumarez already knew the Victory, for he had been her seventh-lieutenant in 1780. By this time, she had long been overtaken by much larger ships, the 110-gun Ville de Paris and Hibernia were already in service, and the 120-gun Caledonia was about to be launched. Victory herself, though reduced to a second-rate, was still a three-decker and provided grandeur as well as space for a headquarters, for such ships were extremely rare in the Baltic. The large ships of the Danish Navy had been captured or destroyed, whilst the Swedes had nothing bigger than a 74. Under Catherine the Great (1762–1800), the Russians had built a class of eight first-rates of the Ches’ma class based on the Victory’s lines. They had fallen into decay by this time, but the 110-gun Gavriil, an expanded version of the class, had been launched in 1802 and was still in service. She was accompanied by the 130-gun Blagodat, built in reaction to the Spanish Santissima Trinidad. She had only once ventured beyond the Gulf of Finland to attack Swedish Pomerania in 1805.21

The Victory already had a certain amount of historical value after Trafalgar but she was not too valuable in what might be a risky situation, and suitable for a command which was regarded as less important than the North Sea, Channel and Mediterranean. The Captain of the Fleet was George Johnstone Hope, a member of a Scottish naval family who had commanded the Defence at Trafalgar. Though he was highly competent, relations could become strained with too much time together and Saumarez complained to his wife in 1811 of, ‘passing so much of the day together, which often become[s] dull et trés ennuyant… we are too great for each other…’22 The flag captain was another Guernsey man, Phillip Dumaresq, a cousin who had served under him for much of the wars and was his flag lieutenant at Algeciras. James Squire became master of the fleet with overall responsibility as adviser to the admiral, while Joseph Nelson was the master of the Victory. Saumarez was deeply religious and William Cooley was appointed chaplain. William Rivers stayed on as gunner, but the ship had two new standing officers – James Phillips became boatswain while John Barton the carpenter was superannuated and replaced by Edward Hogben in February.

After the death of Pitt in 1806, British politics tended to be fragmented and divided. The King was out of action, due to what was believed to be madness, from February 1811 and his son the Prince Regent was not respected. The period saw a duel between the cabinet ministers Castlereagh and Canning and the only assassination of a British prime minister, Spencer Perceval, in 1812. There were three different First Lords of the Admiralty in 1808–12, while public and parliamentary attention was focussed on the expanding war in Spain rather than on the Baltic, which provided far fewer dramatic events. All this gave Saumarez an unusually free hand in politics as well as naval affairs.

The Victory was ready for sea by 17 March, but Saumarez’s arrival was delayed while a new scheme was set in place to provide a force of 10,000 troops in support of the Swedes, who faced a possible invasion across the narrow Oresund from Denmark. Saumarez finally arrived on board at the Nore on 22 April and hoisted his flag. He sailed on the 25th and anchored in Hawke Roads off Gothenburg on 9 May. The Victory became a centre for social life in a town which had expanded vastly to deal with British trade. Marianne Ehrenström, wife of the Swedish military commander, was one of those who visited. She wrote, ‘it became a race to get hold of a skiff to look closer at this fine spectacle, this imposing picture formed by three ships of the line, frigates and more than two hundred sail.’ She and her party hired a sloop and when they arrived alongside Victory, ‘English officers showed themselves on deck to receive us, some embarking on our sloop to help the ladies to be hoisted on board in large barrels, formed as armchairs and dressed in different flags to bring them over the high sides.’ Saumarez showed her the spot where Nelson had died, and she looked at the officers’ cabins, which she considered very comfortable and with shelves containing the works of the latest British authors. She found the seamen’s food was ‘tasty soup, highly-flavoured and well-cooked meat and good white bread.’ She visited the sick bay, ‘a paragon of tidiness and functionality.’ There were only two seamen in it, one of whom refused to take his medicine. She spoke to him in English, ‘“Do not refuse me this. Spare your life for your country and its friends”. He sat up like a spring, smiled at me, took the cup and swallowed it in one gulp and said “God bless you, dear Lady.”’ A few days later there was a ball on board with the ships dressed overall, and the visits were returned with Saumarez and his officers spending time ashore.23

Sir John Moore, now a lieutenant-general and commander-in-chief of the proposed Swedish expeditionary force, arrived on board the Victory by ship’s boat. He had been to Stockholm to discuss plans with the erratic King Gustav IV Adolf, but his tact had not improved since he had clashed with Hood and Nelson off Corsica in 1794. He dismissed the King’s ideas out of hand and found himself under house arrest, from which he escaped. It soon became clear that there was no way in which the British troops could intervene effectively, while Saumarez found it a trial as his ship served as the headquarters for both the navy and the army. He endured ‘a week of considerable anxiety and bustle, for exclusive of much official business… I have in addition had most of the general officers to dine with me and yesterday we were not less than twenty at dinner.’ Saumarez was not sorry when the troops were sent home in transports, for a new front against Napoleon was developing.

The Spanish had revolted against French rule and that included 12,000 men in Denmark in the service of Napoleon who gathered on Langeland, Funen and other islands and wanted to go home. The Victory was needed to cover the transports which took them away, and delayed Saumarez’s joining with the Swedish fleet in their base at Karlskrona. As a result, he missed an action off the entrance to the Gulf of Finland, when Hood and Captain Thomas Byam Martin (who had been so impressed with the stern of the Royal George as a boy) attacked a much larger Russian force and destroyed the Sevelod. It was the Russians’ first experience of the ferocity of a British naval attack, and it made them extremely wary of it afterwards. It also showed that the Swedish fleet was poorly manned and trained. The Russians were now blockaded in Port Baltic or Paldisk near Reval, now Tallinn. Saumarez had to choose whether to risk all and attack them behind their defences, but decided against it and offered terms, which the Russians rejected. Hope went on leave and Byam Martin of the Implacable took over as captain of the fleet, but soon found he had to ‘engage in a much more arduous duty than I expected.’ He was not disappointed when Hope returned after a month.24 Saumarez returned to Karlskrona at the end of September, then sailed for England in the Victory on 3 November, leaving Keats in charge for the Baltic winter when fleets were immobilised by ice over much of the sea. He was able to confer with ministers (who were not entirely satisfied with his lack of aggression) and visit his home in Guernsey.

To Spain

There was no such rest for the crew of the Victory. At the other end of Napoleon’s empire, Sir John Moore had taken charge of the British army in Spain but, after a brilliant campaign, he was forced to retreat to the north-west by larger forces under the personal command of Napoleon. The Victory, now captained by John Searle, was one of the ships chosen to evacuate the army, along with a large fleet of transports. She was sent to Vigo with the even larger Ville de Paris, a 98 and three 74s but there was some doubt about where the army was to be found, compounded by a dragoon who got drunk and failed to deliver a vital message. Eventually, they were ordered to Corunna but the ships had to be towed out of harbour in light winds. The Victory was off the port by the evening of 14 January 1809, but was unable to enter ‘from the great number of transports working in.’ Eventually, she anchored at 11.30am the next morning and in the afternoon the crew observed, ‘the British army on the heights near the town in action with the French army occupying the next heights.’ Boat crews worked hard to embark troops and baggage, including thirty officers, 291 other ranks, twenty-one women and one child of the 81st Regiment of Foot. There was more heavy firing ashore in the afternoon of the 16th and next day the British troops retreated into the town, while the Victory’s carpenters fitted up berths for wounded men. The French set up a battery to fire into the harbour which caused many of the transport ships to ‘cut and run’ before they were fully loaded and even the Victory had to shift her berth half a mile further out. Sir John Moore was dead by this time and according to Thomas Wolfe’s famous but inaccurate poem:

We buried him darkly at the dead of night,

The sods with our bayonets turning.

The embarkation of the army was completed early in the morning of the 18th and the boats were hauled in, though they had to be hoisted out again to help the Barfleur transfer some men. They set sail that afternoon, while the body of Lieutenant Hanwell of the 81st was committed to the deep. They headed for Plymouth but encountered strong gales on the way and had to reduce sail. They dropped anchor in Cawsand Bay near Plymouth on the morning of the 23rd, but it took several days to get the passengers ashore in bad weather. 25

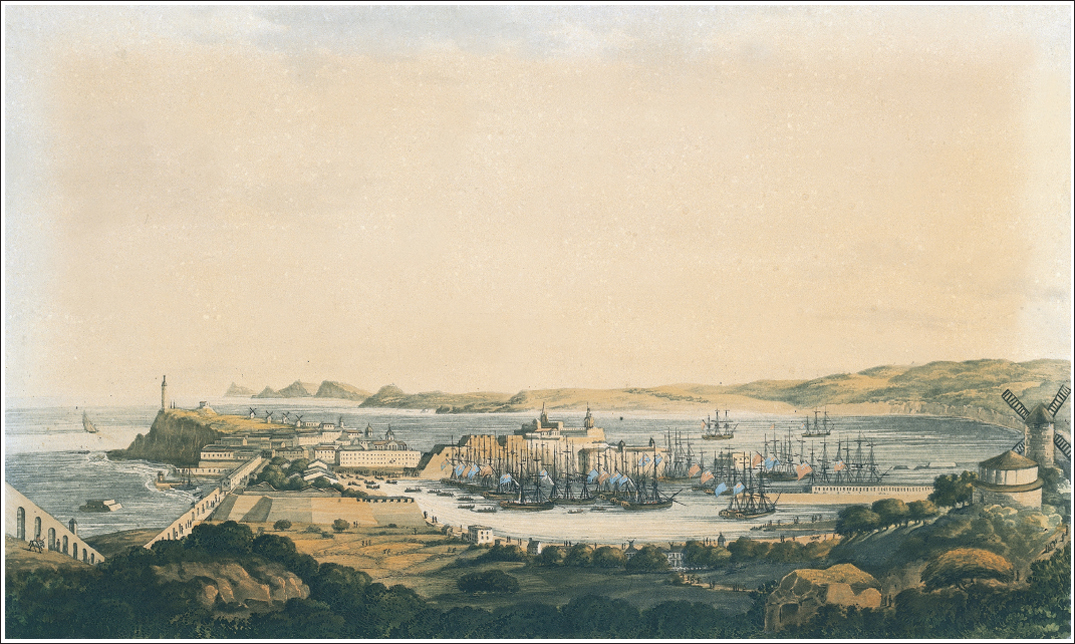

The evacuation of Corunna as seen from the hill above the town. The Victory is not to be seen in this picture, and there are very few ships offshore, but the harbour is very crowded, mostly with merchant shipping.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PZ0007)

Turmoil in Sweden

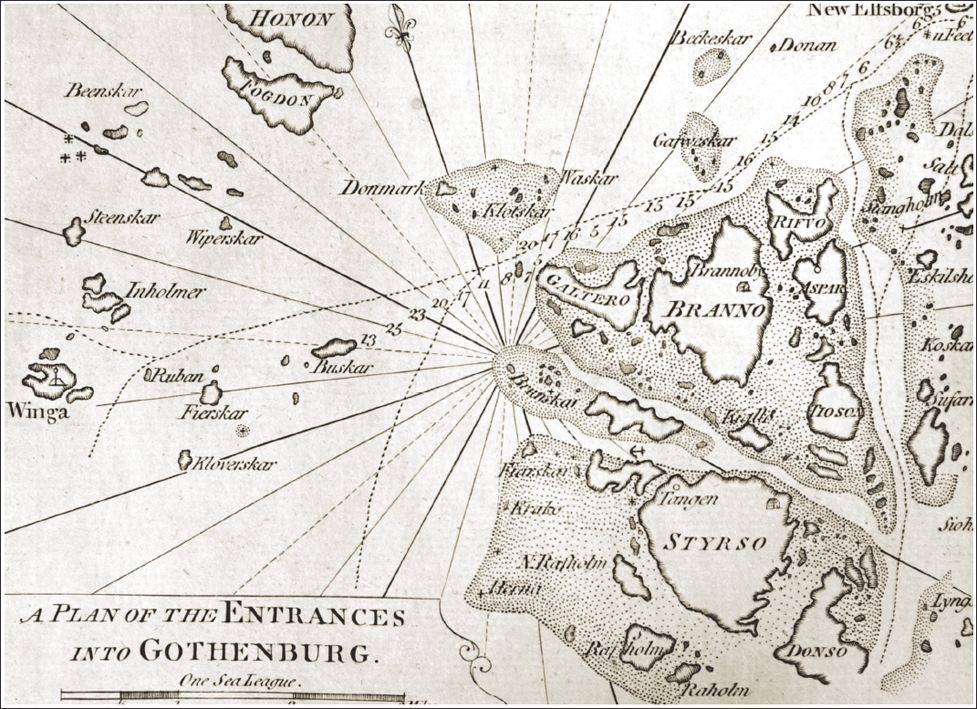

Victory arrived back off Gothenburg on 8 May and anchored in Vinga Sound (known as Wingo to the British) fourteen miles out of Gothenburg, which was now her regular base. According to Masters Squire and Nelson, ‘the best place to anchor in Wingo Sound is a line between Butto and Busker, in 12 or 14 fathoms water, good holding ground.’26 During Saumarez’s absence there was coup against the unstable King Gustav IV Adolf, witnessed by Lieutenant John Ross of the Victory who had been sent to liaise with the Swedes:

…The conspirators… entered and told the King he must leave Stockholm. Drawing his sword, His Majesty made a pass at one of the conspirators; in the mean time, the General seized the staff of power, and ordered the others to seize the King… [He] immediately escaped and .. called loudly for help. Some of the conspirators… called to the soldiers on duty, “The King is mad;” on which they secured him, and in the evening he was removed to Drottingen…27

His place was taken by his uncle as Charles XIII and he was accepted by the British, though not formally recognised by them.

An elaborate convoy system was needed to maintain the Baltic trade, organised by the Admiralty, the merchants William and Phillip Emes, Saumarez during his winter visits to London and by his secretary Samuel Champion on board the Victory in Vinga Sound. The trade was mostly carried in ships registered in neutral countries such as the United States, with carefully forged papers to show that they were trading with countries other than Britain – though they also carried permits from the British Privy Council, and their naval escorts would ensure that they did not head for French territory with valuable naval stores. Outgoing ships gathered in the Thames, Humber, Forth and Orkney and sailed in fortnightly convoys. They anchored in Vinga Sound under the protection of the Victory and her consorts, where they were split into groups for the dangerous passage into the Baltic proper. At the beginning they used the straight and narrow passage through the Oresund, or the ‘Sound’, as the British called it, but that proved too dangerous. They were obliged to use the intricate channels through the Storebaelt or ‘Belt’, often spending several days and anchoring at night under the protection of British ships of the line. Though the Danish Navy had lost all its large ships, they built up a fleet of more than 280 rowing gunboats which could harass trade and even overcome frigates in a calm on the narrow waters – in October 1808 they even attacked and damaged the 64-gun Africa.28 Once out of the Belt, the next danger was the privateers stationed in the Danish island of Bornholm and the tiny Ertholms, which Saumarez declined to attack in 1808–9. Once clear, the convoys dispersed for they could not appear off their destinations under obvious British escort. The returning convoys, mostly loaded with naval stores, assembled at Karlskrona or Hano off the Swedish coast. They often built up to considerable size especially if delayed by bad weather, or towards the end of the season when ship owners tried to fit in a second voyage – 200 or 300 ships were not uncommon, and even convoys of 500 might be seen. The passage through the Belt was always hazardous, but by 1809 the system was well established and the trade was maintained.29

The Danish royal line was in danger of failing due to lack of issue and a crown prince had to be elected by the Rikstag of the Estates, who made a surprising choice in August 1810. Jean Bernadotte came from a middle-class French family and served as a private in the pre-revolutionary army before rising to the rank of marshal through his ability. He commanded French forces in the Baltic region and he impressed Swedish officers with his good treatment of prisoners. Other candidates as crown prince were too close to the enemies in Denmark and Russia, while the army felt the need for a soldier as national leader. At first, Saumarez was horrified at the choice and wrote, ‘I very much apprehend that the election of a French general to the Heir Apparent to the Crown of Sweden must be with a viewto detaching the country from all intercourse with England.’30 But he later moderated this view and granted Bernadotte permission to cross the Belt from Denmark in the Swedish royal yacht. Two convoys totalling of 1,124 ships had gathered because of delays, and they formed a part of a demonstration of British sea power. According to Ross:

The day was very fine; the fleet was anchored in a close, compact body, with the Victory in the centre, bearing the Admiral’s red flag at the fore, surrounded by six ships of the line, and six frigates and sloops disposed for the complete protection of the convoy. The yacht, with a Swedish flag, containing the Crown Prince, passing within a mile of the Victory, was distinctly seen, and escorted by some barges from the men of war until past the whole of the ships; the convoy soon after weighed anchor, when the Royal stranger had the pleasure of seeing them all under sail and proceeding to their destination, regardless of the enemies who occupied the adjacent shores.

The sight was especially dramatic to a landsman like Bernadotte, who later told Ross that it made a deep impression and ‘conveyed some idea of the wealth and power of the British nation’. It was ‘the most wonderful and beautiful sight he had ever beheld, being one of which he had never formed an idea.’31

Bernadotte soon showed that he was not Napoleon’s puppet and began to devote himself to Swedish national interests. This included relations with Britain, partly to maintain trade, but also to gain possession of Norway from Denmark in compensation for the loss of Finland to Russia. That could only be done with a British alliance, since the Danes were now staunch allies of France. Nevertheless, Bernadotte was under strong pressure from Napoleon to go in the opposite direction. On 17 November 1810, two days before Saumarez’s main fleet left the area for the winter, Sweden declared war on Britain. To many, the situation looked bleak indeed, with no ally left in the Baltic, and some argued that only another devastating attack had any chance of remedying it. Saumarez knew better, his contacts with Sweden’s rulers convinced him that the declaration was only formal and that the war would not be prosecuted.

Back in Portsmouth for the winter, the Victory was prepared for another trip to Iberia, this time to bring troops rather than evacuate them. By this time General Sir Arthur Wellesley had been raised to the peerage as Viscount Wellington and had adopted his strategy of conducting campaigns in Spain in the summer while retreating behind the lines of Torres Vedras around Lisbon for the winter. On 16 January 1811 the Victory’s lower deck guns were laboriously taken out and soldiers’ beds and pillows were brought on board. The marines moved down to the lower deck leaving the middle deck for the soldiers – 717 officers and men including Generals Byrne and Long and their staffs, the 1st Battalion of the 36th Regiment of Foot under Lieutenant-Colonel Basil Cochrane, and various replacements and specialists. Most of them were brought on board at St Helens on the 28th.

The ship sailed on the 30th as part of a squadron under Rear-Admiral Sir Joseph Yorke in the 74-gun Vengeur but there was a bad start – Seaman John Atkinson fell from the booms and was killed. Out in the Channel, the winds were contrary and the ships moved out into the anchorage at Torbay. Over the next two weeks they tried three times to make progress but were driven back each time, until they finally got away on 15 February. Progress was still slow with ‘fresh gales and squally’ alternating with ‘light breezes’ recorded in the ship’s log book. When land was sighted on the 23rd it was only a distant view of Cape Finisterre, some forty miles away. The fleet suffered further loss when William Fitzsimmons fell overboard and was drowned and there were disciplinary problems. Four men were flogged on the 27th and later Lieutenant Kentish was put under arrest for leaving the deck during his watch. The winds were better by 2 March and next day the Lisbon pilot was taken on board. The ship moved up the River Tagus in stages, and both services were probably relieved when five boats arrived alongside the Victory in the morning of the 5th to take the soldiers ashore. For the sailors, the voyage home was not much better, but they passed the Needles to enter the Solent on 26 March.32

Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte, crown prince of Sweden and founder of a dynasty.

(Musée de France)

A Phoney War

Saumarez arrived back at Vinga in the Victory on 2 May to face a new situation. Warships often served, in effect, as floating embassies in days when communications were slow and the man on the spot, whether diplomat or naval officer, had to make the decisions. It was the case even more so for the Victory now as, of course, Britain had no formal diplomatic relations with Sweden and contact was maintained largely through Saumarez and his flagship. The situation was clarified when Baron Tawast, the Swedish military commander at Gothenburg, came on board the Victory under a flag-of truce ostensibly to discuss the exchange of prisoners; but informed Saumarez, ‘…that he was instructed to communicate with me, in the most confidential manner, that it was the earnest wish of the Swedish Government to keep on the most amicable terms with Great Britain; and it was not intended, under any circumstances, to commit any acts of hostility whatever.’33 Saumarez acted with restraint over some merchant ships that had been seized at Carlsham and their cargoes sold. He also had to restrain his captains who did not share his indifference to prize money, and he even ignored an Admiralty order to stop Swedish trade, until it was rescinded a month later. He was in close contact with the Governor of Gothenburg, Count Axel von Rosen, who rowed himself out to the Victory in June 1811 to confer with the admiral in secret, spending eight hours in the boat because of unfavourable currents, covering his hands in blisters and ending up miles north of the city so that he had to walk back.34

A few of Victory’s crew had a taste of action in September. There was intelligence that two Danish gunboats were sixty miles to the south between Vinga and Anholt Island planning to attack a homeward bound convoy. The Victory’s pinnace and yawl were put under the command of Lieutenant David St Clair and Midshipman Edward Purcell and sent out to meet them. Despite strong fire and a defensive position among the rocks, they boarded the boats which had five times their own crew, and captured them. Purcell was promoted to lieutenant.35

As the year’s convoy season drew to a close, bad weather and contrary winds delayed several sailings while the second-rate St George was dismasted and lost her rudder. Saumarez considered the possibility of leaving her behind off Gothenburg, but was persuaded to let her sail. He arranged the ships into three groups for the return to England. The first included the Victory, three 74s and two frigates, the second consisted of the St George being towed by the Cressy, the veteran 74-gun Defence and a frigate, while the third comprised a convoy of merchant ships plus an escort. They sailed on 17 December but the merchantmen failed to clear the Skaw at the head of the Jutland coast. Towards nightfall on the 19th, the Victory had a last glimpse of the lights of the St George group and by the 23rd, ‘the storm increased with inconceivable violence: the Victory was scudding under close-reefed main topsail.’36 By the 24th they were off the Suffolk coast. At Spithead two days later, Saumarez reported his arrival to the Admiralty but noted in the margin, ‘I am uneasy about the St George.’ He was right, she and the Defence had been driven onto the D anish coast with the loss of more than 1,300 men. The Victory’s sailing qualities had saved her from one of the greatest disasters in the navy’s history.37

The approaches to Gothenburg, showing the main channel leading to the top right corner of the chartlet, with the anchorage off Winga Island on the far left.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Coasting Pilot, 9931–2001)

The fateful year of 1812 began with rapidly worsening relations between France and Russia, whose leaders had been as encouraged by Sweden’s resistance as they had been chastened by Saumarez’s ships. The admiral hoisted his flag in the Victory at the Downs on 14th April, sailed two weeks later and arrived at Gothenburg on 3 May. Peace negotiations with Sweden were already in progress and war between France and Russia was not far away. In August, Baron von Platen wrote the ultimate eulogy:

You have been the guardian angel of my country; by your wise, temperate, and loyal conduct you have been the first cause of the plans which have formed against the demon of the Continent. He was on the point of succeeding… Two couriers have arrived this night from the head-quarters of the Emperor and the Prince. War was declared on the 24th of July… If providence have not decided something against all probability, Bonaparte will be defeated, humanity will breathe again, and Europe be once more raised up.38

Napoleon had begun his ill-fated invasion. The role of the British fleet was now largely passive, except that Byam Martin led a force which helped the Russians during the siege of Riga. Saumarez was honoured with a diamond hilted sword valued at £2,000 presented by Bernadotte, while the Admiralty sent their ‘marked approbation’ of his ‘zeal, judgement and ability’ during the last four years. They praised, ‘your attention to the trade of his Majesty’s subjects, and your conciliatory, yet firm conduct, towards the Northern Powers… [which] have been justly appreciated by the courts of Sweden and Russia’.39 But Saumarez would have to wait for a peerage until 1832, after his friends in the Whig Party took power.

A large fleet was no longer needed in the Baltic, Saumarez retired and the Victory was laid up. However, she was still considered suitable for active service in the middle of 1813. John William Croker, the First Secretary to the Admiralty, produced a wide survey of the ships available for coming campaigns and noted, ‘if the services of another line of battleship should be requisite, their Lordships may avail themselves of the Victory at Portsmouth, a ship that we did not expect to be paid off until the end of the year 1814, and which we apprehend may be brought forward in a very short time.’40 She was part of the ordinary at Portsmouth, in mooring position number eleven with 22ft 8in of water at low tide, one of six ships under the charge of Superintending Master Thomas Edwards. She had a crew of five officers and five men.41 By that time, Napoleon had been driven out of Russia with enormous losses, a new coalition had been formed against him including Russia, Sweden and Prussia, and they would soon defeat the French in the ‘Battle of the Nations’ at Leipzig, while Wellington’s troops, some of them carried to the theatre in the Victory, crossed the Pyrenees to invade France from the south. On 11 April 1814, when the Emperor Napoleon abdicated and was exiled to Elba, the Victory could claim to have done more than any other ship to ensure his downfall.

Repair at Portsmouth

The Victory began yet another repair after a survey of 1813, though it expanded as more defects were revealed. On 15 October, the Portsmouth Dockyard officers thought she could be ‘brought forward without entering a formal repair, by shifting the decks and such materials as are visibly defective, and by giving her additional strength where it can be with propriety be introduced.’ The Navy Board agreed that this should be done, ‘when a dock will be vacant, that may be appropriated without interfering with ships in commission.’ The Board made it clear that they did not approve of ‘stopping up so many large docks, and particularly the deeper ones’, so one would not be ready for the Victory until February.42

In 1808 the damage to the Victory at Trafalgar had largely inspired Seppings’ new round bow, and that became standard in 1811. ‘In that year, when the Right Hon Charles Yorke was at the head of the Admiralty, I presented to him a model showing on one side the bow of a ship of the line with the then usual form, and the other with a circular one carried up as above mentioned; and so fully satisfied were Mr. Yorke and the naval members of the Board of its advantages, that orders were in consequence given for its general adoption in His Majesty’s Navy’. But she was not fitted with Seppings’ next and more important invention, the diagonal bracing, which would greatly strengthen the hull and make it possible to build much longer ships. It was probably just a matter of timing – Victory was under repair from March 1814 to January 1816, the Seppings system was not standard practice until 1817. But it soon became clear that ships fitted with diagonal bracingwere much superior, and eventually they would be able to be fitted with engines, while much longer ships could be built for a given number of decks. Five 120-gun ships of the Caledonia class were begun in the ten years after 1815,205 feet long on the gundeck, measured at 2,600 tonnes and twenty percent larger than the Victory.

The old square bow is shown on the top view of this model of a two-decker, still painted with the yellow of the Nelson chequer. The view below shows the round bow as fitted in 1814–16, with the black and white colour scheme which became common at that time.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, SLR2185)

The End of the War

Thus the Victory was not available when the Royal Navy was mobilised again after Napoleon escaped from Elba and took power in France. Designs for the head and stern were sent to London on 20 June, just two days after Wellington and Blücher defeated Napoleon at Waterloo. The actual plan is missing from the file, but the head would cost £65, plus banisters at the stern at £65 each. Napoleon surrendered to HMS Bellerophon which had fought in Collingwood’s division at Trafalgar. He was taken to Plymouth Sound then put on board the Northumberland to take him to a far more distant exile on St Helena. In December the repairs to the Victory were only held up by a shortage of joiners who were mostly employed on internal work – they were overcome by ‘the very great pressure of business…’ though the Victory was ‘in every other respect ready for them.’ The Navy Board agreed that the ship should be taken out to free the dock, and the rest of the work should be done afloat. By January 1816 the ship was ‘in a state to enable us to take in hand the store rooms and cabins on the orlop deck, and the Portsmouth officers asked how they were to be fitted. The Navy Board sent them a plan of the Caledonia as a guide.43 Repairs were completed soon afterwards, at a final cost of £79,772, and the Victory was afloat and ready in a strangely peaceful world, after twenty-two years of almost continuous war.