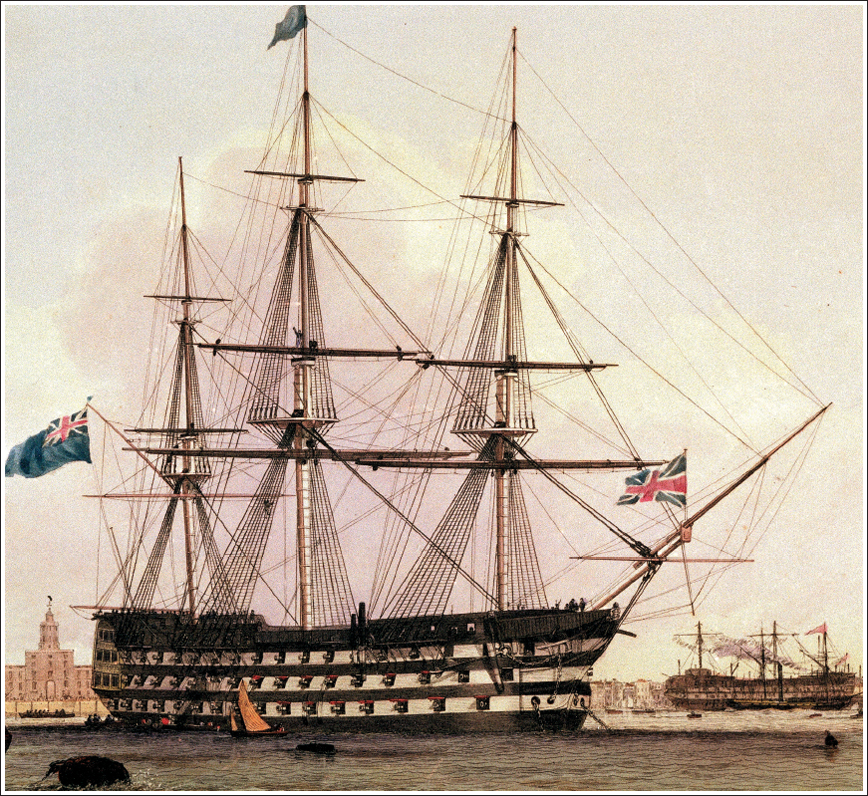

Flagship at Portsmouth

The Victory now flew the flag of the commander-in-chief at Portsmouth, who was responsible for the ships afloat and in commission, while the dockyard dealt with repairs and the Navy Board commissioner was, in effect, a liaison officer. Portsmouth had a large number of service vessels, including old ships which would never go to sea again but were useful as store ships, receiving ships for pressed men, and sheer hulks which were used to fit masts to other ships. In addition, there were a dozen prison ships in the harbour, a fate which Victory had narrowly avoided in 1799 – though these were now used for civilian convicts rather than prisoners of war. Victory was never reduced to the status of a hulk, which would have altered her appearance greatly. Instead, as a flagship, she carried a full complement of masts and guns. In 1828, the middle deck was fitted with ‘Sir William Congreve’s short twenty-four pounders’ and the upper deck had 9ft long 12-pounders. Apart from men passing through, the ship had ninety-eight petty officers and seamen in June 1828. Twenty-eight of these were away manning the Scorpion tender which patrolled the Solent, four of them manned the captain’s gig and twelve the admiral’s barge. The ship’s band had fifteen men and there were six wardroom and captain’s servants – the admiral’s servants were listed separately. There were six signalmen and yeomen of storerooms, a purser’s steward and his mate, a cook and mate, an armourer and mate, a master-at-arms and two ship’s corporals for police services, two men to attend the five who were ‘sick on board’, nine carpenter’s crew for maintenance and two writers or clerks in the admiral’s office.1

E.W. Cooke’s 1828 print shows the Victory still fully rigged and equipped for service and flying an admiral’s flag at the mainmast. A small steamship can be seen to the right, a foretaste of things to come.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PU5983)

The C-in-C had no actual fleet to command, just ships fitting out for longer voyages. With the dockyard and other shore bases in charge of the material aspects, his responsibilities were mainly to do with personnel. He often took on midshipmen and cadets, perhaps giving them some preliminary training before sending them to seagoing ships. As to the lower deck, in 1828 the Duke of Clarence (Nelson’s old friend) was Lord High Admiral and ordered that the flagship should take on ‘any able seamen that may offer for general service’. Admiral Robert Stopford went further and asked if he could also take on ‘in the same manner any good ordinary seamen, or shipwrights’2. Many captured smugglers were sent to the ship, having been offered the choice of prison or naval service – they were the only criminals that the navy accepted at this time, for their offences were not anti-social in the sense of robbery or murder, and they were often good seamen. In 1826, for example, forty-six-year-old Alexander Ferguson of Dumfries was taken – he was 5ft 5in tall with ‘sallow complexion, woman [tattoo] on left arm’ with hazel eyes.3 In June 1825, Stephen Church found a scuttle or hole in the sick bay, where the bars had been set too far apart. He climbed through the starboard bow gunport, using a rope which had been left hanging there, and was not spotted by two marine sentries.4

Deserters and miscreants from other ships came on board the Victory, for example David Paine in 1828. Captain Elliot objected to his being transferred to another ship on the grounds that he might be reinstated in his rating as petty officer – his misconduct was ‘of long-standing’ and he had been repeatedly warned about it.5 In 1829 the Victory had to cope with Boy John Davey who had already deserted from two ships. He was sent on board from the naval hospital and it was not felt necessary to guard him, but he stole clothes from some of the supernumeraries on board, then got ashore and was caught a few miles beyond Portsmouth. He was a ‘worthless blackguard’ who would ‘never be of the least use to any ship.’ Around the same time, James Manning, a returned deserter, was complained ‘by some of the boys of his taking improper liberties with them’ so he had to be confined on the upper deck.6 The C-in-C also had responsibility for the naval defence of the area, and the coastal blockade which was maintained against smugglers. In 1827 Stopford departed on a tour of the local stations, leaving Captain Mingaye of the Revenge in charge at Portsmouth,7

There were considerable doubts about the navy’s system of gunnery. The old system had worked well in 1805, when speed of fire was all-important and Nelson believed that ‘no Captain can go very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an enemy.’ But in 1812 the navy came up against the well-trained crews of American frigates and suffered several defeats. At the same time it was increasingly involved in shore bombardment and, off the coast of Spain in 1812, Sir Howard Douglas of the army remarked that bad gunnery, ‘made him tremble for the laurels of the navy.’8 Trials of new systems of gunnery were sometimes carried out on board the Victory, for example in 1818, with ‘a gun mounted upon a carriage constructed by Commander John Eole’. Gunnery training was still carried out on board the Victory and in 1824 one H. Hammerton kept a gunnery notebook of his training on board. Loaded guns could not be fired from the Victory herself where she was moored, but one of the ships in ordinary was fitted with a single gun for practice. However, in 1829 Commander George Smith suggested a specialist gunnery training ship in the harbour. He found that the old 74-gun Excellent of 1787 was moored in the best position for practice firing and in June 1830 Smith was appointed ‘Supernumerary Commander of the Flag Ship at Portsmouth’ to take charge of her. Two years later the Excellent ceased to be a tender to the Victory and became an independent ship in commission – a momentous step, the beginning of the first real training system in the Royal Navy.9

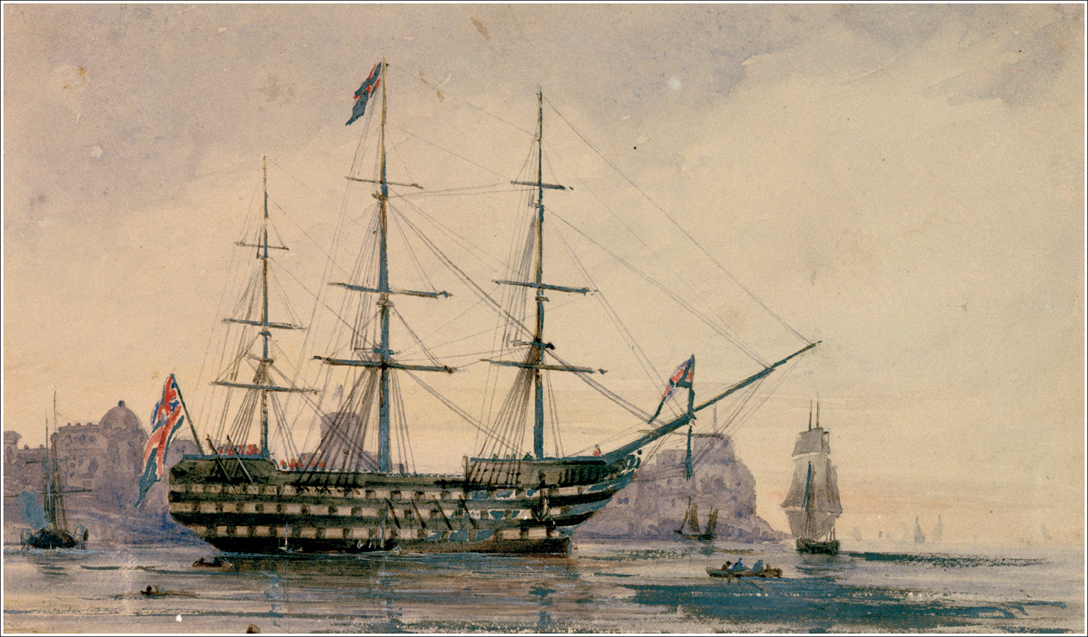

The Victory is in the centre of this print by Fores in 1851, with the royal yacht Fairy under steam to the left, probably taking Queen Victoria to her home on the Isle of Wight. The hulk Dryad, formerly a 36-gun frigate, shows how drastically the Victory’s appearance might have changed if she had been reduced permanently to harbour service. The semaphore tower in the right background appears in many views of the Victory in harbour.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PY9197)

Reduced to the Ordinary

The commander-in-chief at Portsmouth often had a Nelson connection, and none was stronger than that of Thomas Foley. In 1798 he led the fleet into Battle of the Nile in the Goliath, almost certainly using his own initiative to attack the enemy on his unprepared side. In 1801, he was Nelson’s flag captain at Copenhagen when Nelson famously put his telescope to his blind eye. Foley was also loyal to his old comrades and arranged a position for the grandson of a midshipman killed at the Nile. He arranged a passage back to Africa for John Duncan, ‘a black man and a native of Sierra Leone’, who had recently been paid off from the Victory.

Foley decided to have his headquarters ashore and arranged for the Victory to be paid off as a flagship, with the mates and midshipmen transferring to the 120-gun St Vincent under Captain Parker. The sixty-four-year-old carpenter of the ship, John Garbutt, applied for superannuation after thirty-seven years of service which had left him with defective vision. The schoolmaster, Mr Harkness, was ‘a youngman every way qualified for that situation’ who had come down from Edinburgh in 1827, but missed the examination in the Royal Naval Academy and asked to be paid for the two months he had served unqualified, before passing with one of the best results that Dr Inman of the Academy had ever seen – but this, the Admiralty clerk noted tersely, ‘cannot be complied with.’

It was reported that the Admiralty intended to cut the Victory down to a two-decker of 84 guns, which would perhaps have maintained her status as a fighting ship but would have destroyed much of her historical value, including removing the deck where Nelson was wounded. This initiated a campaign led by the actor John Poole. He wrote, ‘…such a ship is [a] national heirloom, and ought to be preserved as a sacred relic… why do they not entreat that she may be preserved as she was at the day of Trafalgar?’10

When the Victory was not reduced, the press claimed a triumph and in July the Standard reported:

In accordance with the feelings of the public, the Admiralty have abandoned the intention of cutting down the Victory (so endeared to us by many associations) to a 74 [sic]. Since it was understood that this step was contemplated, the public have been loud in their lamentations that such a national object of interest should not be suffered to remain unaltered. Consulting, therefore, with the general wish, the Admiralty have not only relinquished their first intention, but have decided that she shall be fitted to receive the pendant of the captain of the ordinary, thus rendering the Victory an object of double interest.11

Poole and his supporters claimed to have saved the Victory, though there is no evidence that the Admiralty actually had a plan to reduce her physically rather than merely in status. On 4 October 1831 the Admiralty allocated the ship a complement of 200, including a captain and two lieutenants, six warrant officers and fifty marines. They ordered her to be ready to hold a court martial on the 6th, and that was to be one of her new roles.12

Portsmouth Harbour now had a number of steam vessels, mostly used for carrying messages and towing ships in and out of harbour. The Victory encountered steam power in a rather different form, as a dredger owned by the firm of Joliffe and Banks cleared the waters around her mooring during 1830, while convicts were employed to remove the silt from barges. The dredger was so efficient that the Portsmouth officers wanted to buy one at a cost of £5,000 but the Navy Board discouraged them, as it would not find constant employment.13

The fourteen-year old Princess Victoria first visited the ship as part of a south coast tour on 18 July 1833. She was shown the spot where Nelson fell and where he died, misquoted his famous signal as the rather banal ‘Every Englishman is expected to do his duty’ and, rather like Marianne Ehrenström had done twenty-five years earlier, she sampled the sailors’ food. ‘The whole ship is remarkable for its neatness and order’ she wrote, ‘we tasted some of the men’s beef and potatoes, which were excellent, and likewise some grog.’14 Eleven years later she returned as Queen. On Trafalgar Day 1844 she and Prince Albert were returning from their new home at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight when they noticed flags flying from the Victory and a celebration taking place. The Queen demanded to go on board and was taken to the quarterdeck to view the plaque ‘Here Nelson fell’. She then went down to the cockpit but there was confusion on the way. ‘…after descending the ladder, …Her Majesty was run against by a powder monkey, who was bringing up a fresh supply to salute the Queen on her departure. Her Majesty was almost overthrown by the concussion, but bore it with the most gracious and condescending affability.’ She continued down to see ‘the figure of a funeral urn emblazoned on one of the knees of the ship, surmounted with the words, ‘Here Nelson died.” Her Majesty remarked that ‘the orlop deck was not so high in the Victory as in other men-of-war which she had visited.’15

The Victory’s obsolescence as a warship was slow-burning. One factor was the changing armaments of ships of the line to make them more uniform, with 32-pounders on each deck. Thus in 1852 the naval architect John Fincham wrote:

Whilst we regard the Victory and Caledonia as excellent ships during the last war, it is to be remembered that they carried a comparatively light armament, consisting of 18 or 24-pounders on the middle deck, 12 or 18-pounders on the upper deck, and 12-pounders and carronades on the quarter deck, forecastle and roundhouse. Their breadth, however, was too small to give enough stability with the modern system of armament which disposes a much greater amount of weights on the upper decks.16

Steam power continued to grow in importance, though the paddle wheel was not suitable for a ship of the line as it would block much of the gun armament and be highly vulnerable to enemy shot. The 1830s and 40s saw the development of the screw propeller, and in 1845–46 the Ajax, an old 74 of 1809, was partly converted in Portsmouth Dockyard then towed across the Solent to be fitted with a steam engine and propeller. She came back in 1846, to serve as a short-range steam blockship for the defence of the dockyard and three more ships were converted. In the next stage of the evolution, eight more ships were built or converted as seagoing steam ships of the line from 1851– 54.17 The Victory was not likely to undergo such a conversion, in view of her age and lack of diagonal bracing, but the sailing ship was still not considered obsolete. However, in 1848 Admiral Milne listed her among the ‘non-effective ships’ with a complement of twenty-two officers, fifteen petty officers, forty-nine able seamen, six first-class boys and twenty-four second-class, fifty marines and seven idlers or men who did not keep watch. They were employed ‘embarking new[ly] raised men, marines, troops &c, hospital day boats, rowing guard &c.’18

A Midshipman on Board

Cecil Sloane-Stanley arrived in Portsmouth with his parents in 1850 to be tested for entry as a naval cadet. Appearing at Admiralty House in the dockyard, the family was directed to the Victory and rowed out by a boatman plying his trade from the Common Hard. ‘The interminable chatter of this ancient mariner was happily brought to an end, ‘ere many minutes had passed by our arrival alongside the flagship. After climbing the old three-decker’s steep sides we found ourselves on the middle deck in the presence of a stern-looking official bearing a cane, who demanded our business.’ They were led aft to ‘along room with a long table’ to await the captain, who was Francis Price Blackwood, the son of Nelson’s great frigate captain. The guard presented arms as ‘a tall figure, wearing a boat cloak and glazed cocked hat’ came on board and was eventually ready to receive the candidate in his cabin. Sloane-Stanley was taken for a ‘very unpleasant ordeal’ of a medical examination then tested in arithmetic by Mr Kerr the schoolmaster, who told him, in his Scottish accent, ‘You’ve done verra weel, youngster’. It was largely a matter of chance or personal talent as nothing in his classical education prepared him for such a test – ‘I could have translated a page of Virgil or Ovid with far greater ease than I could have worked a rule of three sum.’ Eventually Captain Blackwood told him, ‘Mr Sloane-Stanley, I have much pleasure in giving you your Certificate, and in welcoming you to a noble profession. May you prosper in it, and tread in the footsteps of that immortal hero who died, fighting for his country on board this same old Victory.’

The young man was given three weeks leave before returning to the Victory. His parents ordered a cadet’s uniform and ‘My school-boy clothes were cast off without a pang…’ He was rowed on board by the same ‘singularly persevering waterman’ who had now attached himself to the family. On board the ship, he was greeted by the first lieutenant as a ‘young Nelson’ and he and his parents went to his future quarters on the gunroom, and his sleeping quarters further below. ‘“Here is your son’s chest,” said the lieutenant after we had proceeded a way into the gloom, “and his hammock will be hung up to a couple of those hooks overhead.”’ The prank of cutting down a boy in his hammock could not be eliminated, and Mrs Sloane-Stanley was not greatly reassured on being told that boys were never cut down ‘by the head’ nowadays. After his parents left, he was allocated amarine servant to tend his clothes and sling his hammock, and met the other members of the gunroom mess. The second master of the ship had been there for several years and was ‘of a surly and unamiable disposition.’ The mate was ‘a capital fellow’ but mostly lived on shore. There were three other cadets, soon joined by two more, and two clerks – the senior one made a ‘Job’s comforter’ speech that Sloane-Stanley would repent his decision to join before long, but the others mocked him behind his back. The young man wolfed down his meal of tea, bread and butter and cold meat. At half past nine, the second master placed a fork in a beam overhead, a traditional way of warning the younger members of the mess that it was time to turn in. Sloane-Stanley had a traditionally farcical attempt to get into his hammock. He did not sleep well, though no one tried to cut him down.

The next day, he had his first experience aloft, going through the ‘lubber’s hole’ in the maintop rather than the outer route via the futtock shrouds. ‘It almost made my head turn to look down, the height at which I was perched seemed to my unaccustomed eyes so tremendous, and I involuntarily tightened my hold on the protecting rail as if to save myself from falling.’ He was shocked when a petty officer demanded the customary half a crown (12 ½ p) for guiding them. He had some leave ashore when he and his colleague were tempted by local girls and next day he began to study navigation, starting with ‘boxing the compass.’ He learned how to keep a log, though in harbour that mainly consisted of recording the movements of other ships. He rebelled against a practical joke of being measured for a ‘cocked hat and a regulation spoon’ by the purser’s steward in his ‘little den of a cabin opening out of the store-room.’ He practised rowing but found the heavy oars of a naval cutter very difficult for a boy, and he nearly drowned while learning to swim off Fort Blockhouse. After two and a half months, he was posted to HMS Ajax for sea service.19

In 1852 Captain Arthur Lowe argued strongly that boys should be trained separately. ‘Flag-ships are the receptacle for all deserters, stragglers, thieves &c., in short, of men of the worst character from other ships; and the boys, with every precaution taken to prevent it, must be more or less thrown amongst them… and by degrees become familiar with their offences and language which, at their early age, must be injurious to them.’ Indeed, two years later a lady visitor was rather shocked when she boarded the ship ‘between a double row of miserable-looking handcuffed deserters’.

Even the life of the boy seamen was not easy, and in 1853 Surgeon William Guland reported:

The transition from domestic to ship life is often so great and sudden as to produce an evident effect upon the general health of the newly raised men and boys. This appears principally to arise from the difference in diet, but also influenced by the air, exercise and clothing….20

In 1856 Chaplain Inskip suggested giving ten naval cadets six weeks training on board the Victory, in view of ‘the early age & scant education of the majority of naval Cadets’ and because of ‘the difficulty of pursuing with proper regularity any course of studies on board a Sea-going ship in consequence of the many interruptions occasioned by unavoidable demands…’21 The authorities were beginning to see that theoretical and practical training should be treated separately.

The Baltic Fleet Sails

War with Russia began in March 1854, leading to the first modern war fever, for the electric telegraph and newspapers made it possible to spread the news fast, while the railway system allowed people to move around. They began to congregate in Portsmouth in huge numbers in March, including an anonymous lady diarist who arrived with her family on the 6th. She was shocked by the tumultuous crowds in the city, including many women who had come to see their soldier and sailor husbands off on a war which might ‘track with terror twenty rolling years’, as the last one had done. The lady, possibly a Miss Rice, was the cousin of a naval lieutenant and found some relief when she visited the Victory:

Captain [John C. D. Hay] received us… and took us over the ship…. We went down to the maindeck, the middle, the lower and the orlop deck or cockpit, where the midshipmen spend some years of their lives and to which the wounded are brought down during action…. Returning to the maindeck, we found the men just going to dinner and one produced a basin of soup which Captain [Hay] was very glad to taste by deputy. It was thick and well-flavoured.22

The party was invited back to the Victory later in the week, and Captain Scott of the Odin suggested they should not risk their lives in a hired boat, especially as the boatmen were charging outrageous prices. He offered the Odin’s launch, but first the party had to run the gauntlet of the crowds at the dockyard gate. They had to shout ‘Odin’s boat’ several times through the keyhole, then the door was opened just wide enough to let in one at a time, while the disgruntled crowd shouted ‘fair play’s a jewel!’ On the way out, the midshipman in charge of the boat collided with several wherries and the watermen, ‘being deprived of their harvest, saluted us with volleys of oaths and curses.’ But, again, all was different on the ship – ‘On the poop of the Victory were Captain Hay and Captain Boyle in full uniform and a triple rank of marines’. They were getting ready to welcome Queen Victoria as she arrived in her train at the South Railway Jetty nearby, though it was feared that she would ‘receive a damp welcome under the cotton umbrellas.’ At noon the Victory fired a salute as the Queen arrived, but that was the old ship’s only role in the ceremony – for the Baltic Fleet was anchored outside the harbour at Spithead and the Royal yacht Fairy took Her Majesty around them in the appalling weather. The Victory was not likely to see action in this war, for apart from her ageing timbers, the diarist observed ‘our newline-of-battleships make her look like a pygmy, huge as she is.’ But her past was not forgotten. Vice-Admiral James Dundas, in command of the Baltic Fleet, remembered that ‘in former wars, when steam was not known, a squadron of British line-of-battle ships maintained a blockade in the Baltic till the end of November’ and wrote that ‘the journals of Sir James Saumarez are now before me.’23

There was another review in April 1856, when the ships returned to Portsmouth, and 240 of them anchored in two rows in the Solent for a mock attack on Southsea Castle and an inspection by the Queen. At last, nearly a century after she was ordered, the Victory was indisputably obsolete for the war had shown that ships without engines could not be expected to fight in modern conditions, and there was no question of fitting one to such an old hull.

The Victory was now in a limbo between a fighting ship and a much-valued relic. There were some who would have disposed of her in favour of more modern ships. R S Dundas, the Second Naval Lord at the Admiralty, wrote to the First Lord in September 1857, ‘I am sorry to find that you are not disposed to find the Victory defective, & if she is once repaired you will not get rid of her for another term of years and I look upon her and the Impregnable as occupying the place of effective guardships & costing money without any countervailing advantage.’24 However, the Victory was docked in October and it was found that a hundred of her frame timbers were defective, along with pieces of keelson, deadwood, riders and ceiling. Part of her planking had been worn out by the chain cables, but her caulking fitted in 1823 was ‘remarkably good’, as was much of the copper sheathing. She only needed a slight repair and caulking, and repair ‘in a cheap manner by piecing with fir.’ After that, the ship would last for several years, though only in ‘still water’.25 But even greater change was afoot and on 20 September 1860 the Victory was saluted by a strange new ship, blackhulled and nearly twice her length. This was the Warrior, built on the Thames as Britain’s first ironclad warship, with the potential to make the wooden warship obsolete. Over the fifteen years of her seagoing life, she would return to Portsmouth many times for maintenance, passing the Victory each time.

Victory and the Law

As flagship, the Victory still had the job of firing gun salutes for visiting royalty and admirals, though there was some doubt about the effectiveness of her old guns. In 1859, there was a visit by a Russian squadron which fired a seventeen-gun salute at Spithead. The Victory duly replied from within the harbour, but in the fresh wind the Russian admiral only heard thirteen guns. The British admiral had to shift his flag to another ship and repeat the exercise to avoid an international incident, and he proposed to do so on future occasions, as ‘the Victory’s guns are so small.’26 Nevertheless, the Victory continued in the role and in August 1865, for example, she fired nineteen guns in honour of a visit by the French fleet.27

Portsmouth boatmen in 1852, ready to take well-wishers out to the fleet assembled at Spithead.

(Taken from Illustrated London News)

The Victory was relatively free from mutiny for all her career, despite some difficulties in the wake of the Keppel-Palliser affair. In November 1859, however, Captain Farquhar of the ship had to lead a party of 200 marines to restore order on the Princess Royal in Portsmouth Harbour – one of the last examples of the old-style mutiny.28 By law, naval courts martial had to be held on board a naval ship – the main exception was Keppel’s trial in 1778, when a special act of Parliament was needed to hold it ashore, but that could not be seen as a good precedent in view of the disorder during and after the trial. To conform to the law, the Victory became the main centre for courts martial in the Portsmouth area. After the loss of the frigate Thetis in 1830, Midshipman William Mends was one of those subjected to the usual ordeal, as reported by his son:

The court sat for three days, and my father being only nineteen years of age, and an unpassed midshipman, having been officer of the watch at the time she struck, was very stiffly catechized by the members. He came out of the ordeal, with flying colours…. This court martial gave him an immense start in the service by bringing him under the favourable notice of many of the most rising men of the day…29

A watercolour by an unknown artist, dated October 1858. It shows the Victory inhermid-nineteenth-century black and white colour scheme, the flag of an admiral of the blue at the head of the mainmast. The Semaphore Tower and Round Tower are shown rather sketchily in the background.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, PAD5979)

One rather unusual case was the trial of Captain Arthur Wilmhurst, who was accused of seeking ‘pecuniary advantage in respect of the wreck of the ship Bremensis.’ The court was presided over by Admiral Pasley, the commander-in-chief at Portsmouth, and included a rear-admiral and six captains, including those of the Duke of Wellington and Victory. The prosecution was conducted by the paymaster of the Victoria and Albert, but he was clearly outclassed by the ‘friend of the prisoner’ or defending lawyer, Sir William Harcourt – Queen’s Counsel, parliamentary orator and future cabinet minister. It was probably not a surprise when Wilmhurst was found not guilty and there was ‘an outburst of applause… and the hearty congratulations of a number of officers who heartily awaited the decision.’30 These occasions were solemn but also ‘a lively scene of brilliant uniforms’, according to Hastings Harris.31 They were not without rough humour according to ‘Miss Rice’, ‘the captains would slyly fill each other’s cocked hats with shavings of paper which descend in showers when the hats are put on during the passing of sentences…’

The Victory also served as the headquarters of the naval police for Portsmouth, though in 1861 Captain Byrne complained that he had only ten men to patrol the area.32 The ship herself was apparently a target for crime in 1865. A convict in Dartmoor Prison overheard two of his fellow inmates planning to steal £2,000 of silver plate by approaching the Victory disguised as fishermen. They appeared to have some knowledge of the security systems on board. ‘…the Mess Room Steward locks up all about 11pm and nearly 12 O’Clock turns the hour glass and walks to chime the bells, from this he turns the glass mid-ships and walks to one forward and does the same, these operations with, it may be, some others occupy him nearly 20 Minutes.’ The captain agreed that ‘the attempt described, though difficult, might be successful’ and decided to check procedures.33

The First Hundred Years

The ship was now 100 years in the water and the Illustrated London News reported, with an eye on Victorian etiquette:

The centenary festival of the famous ship… was celebrated… with a ball… on the upper deck, to a party of some four hundred guests. The upper deck… was covered in with a sort of awning and tastefully decorated with the flags of all nations, and with festoons of evergreens around the masts, while pots of beautiful flowers were ranged on the poop. The ship had been brought alongside the dockyard for convenience of access. The dancing commenced at three o’clock in the afternoon and ended at seven in the evening. The company were therefore in morning costume; and some of the ladies wore their bonnets or hats all the time. The naval officers appeared in their blue frock coats with laced sleeves, or a scarf to denote their rank… Three wine glasses used by Nelson himself were among the furniture of this repast, and many of the guests were permitted to drink from them to the immortal memory of the great English hero.34

A ball to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Victory’s launch. Some of the women are indeed wearing daytime bonnets as described in the report. The width of the ship is greatly exaggerated.

(Taken from Illustrated London News, 15th July 1865)

From the 1850s, the Royal Navy began to move towards ‘continuous service’, by which seamen signed on for ten, and later twelve, years, rather than being paid off after each commission of perhaps three years. By 1860, continuous-service men formed the majority, and by 1890 nearly nine-tenths of men were on such a scheme. This meant that the navy was responsible for its men between ships, but there was no shore barracks except at Sheerness, so larger depot ships were needed. Midshipman Louis Fleet came on board in August 1865, ‘we found ourselves in a gunroom with many others who were waiting for a ship, thus being pitchforked into a gathering of youths with no duties to perform and not a soul who appeared to have any interest in them.’

The mess was dominated by the assistant paymasters, the successors to the clerks of Sloane-Stanley’s day, who were permanently attached to the ship and ‘endeavoured to make us uncomfortable with a certain amount of success.’ One unpleasant custom was being made ‘servants of the Queen’ byhavingthe government symbol of the ‘broad arrow’ cut on their noses:

The subject was held down on a convenient table and the skin over the tip of his nose tautened. Then the point of a penknife was used to scratch the familiar token…. It did not hurt much but it was a bit of an eyesore [or shall we say nosesore?]for a few days until the disfiguring mark disappeared. In our case the indignity consisted in having the operation performed by the aforesaid Assistant-Paymasters.35

The Victory was no longer adequate for the role of depot ship, and at the same time there was pressure to cut expenditure, especially on non-seagoing services – ‘Every man we can reduce in Ports is equivalent to a man added for sea service…’ wrote the First Naval Lord late in 1868. The Admiralty wanted to replace the Victory with the Duke of Wellington, which was around fifty percent larger. Though only built in 1852, she was already in poor condition and the officers at Portsmouth objected to merging the two ships:

Those who remember the different state of things that existed, when all disposable supernumeraries were sent to the Flag Ship, can appreciate the improvement in comfort and condition of the men, and their improved discipline and behaviour, and it would in my opinion be an undesirable and retrograde step to combine the duties of the two ships in one and to revert to what would be tantamount to the former state of things in the Flag Ship before any Reserve of Continuous Service Seamen existed.36

On 3 February 1869 the Admiralty made a decision which smacked of unsatisfactory compromise. The Victory was to be reduced to the status of ‘tender to the Duke of Wellington’ in which role, it was hoped, she might still be useful ‘for the reception of Boys and for other purposes.’ However, there was formal recognition, perhaps for the first time, of ‘the historical interest attached to the Victory’ which had ‘determined my Lords to keep her in her present condition as regards her hull, rigging, and internal arrangements…’ But the Admiralty was not sure of itself for once, and added, ‘my Lords will be glad to receive any suggestions you may have to offer.’

There was outcry in sections of the press and the Army and Navy Gazette reported in February that, ‘an order was received at Portsmouth on Thursday directing that the Victory is to be virtually removed from the books of the navy, and that she is to be at once removed from her present moorings and taken into that lumber of old used-up ships known as the ‘ordinary’.’ A ‘host of county members, watermen and residents of Portsmouth… inundated the Admiralty with remonstrances [sic] since the rumours were set afloat’ but a week later the journal was reassured, ‘we are pleased to be able to remove the apprehension of some of our contemporaries, who are in a painful state of patriotic excitement in consequence of the wrong which it was supposed the Admiralty were about to do to the flagship of Nelson. My Lords never had the slightest intention of either removing or dismantling the Victory.’ Instead, ‘The Victory will be ranked as tender to the Duke of Wellington, and will be employed for the reception of boys and other purposes. For visitors she will continue to possess the same attractions as heretofore and will be as accessible as ever.’37

The Nelson Legend

All this reflected a growing enthusiasm for the memory and fame of Nelson. His reputation had largely declined after the wars, it took nearly forty years to erect the column in Trafalgar Square, and it was only completed with the lions in 1867. After that, it soared, with the increased interest in British naval power both past and present. Boy Sam Noble was delighted to be posted to the Victory after competing his training at nearby St Vincent in 1875, for it was his ‘dearest wish’ to be sent there. Officially, she was used for signal instruction, though Noble did not take to that. As a product of the Scottish education system, he was well schooled in history, and had read Southey’s biography of Nelson, his ‘pet, particular hero’. Despite the signalling, Victory was ‘a cushie job – plenty to eat and not much to do.’ He enjoyed the historical associations:

All about the old ship was interesting, to me fascinating. Here, for instance, on the quarter-deck, was the spot where Nelson fell – on the yet wet blood of his poor secretary. Here, on the poop, the place where the two midshipmen stood while they plugged the fellow on Redoubtable’s mizzen top who had shot him. Here, the point where, being carried below, the Admiral noticed that the tiller-ropes, which had been carried away, were still unrepaired, and ordered them to be seen to. Here, marked by another plate, the spot where, nestling in the loving arms of Captain Hardy, his friend, he died.

Even more, Noble enjoyed showing parties of visitors round – ‘the Janes and Jarges from the country, or the ‘Arrys and ‘Arriets from London down for the Bank Holiday.’ When a party arrived by boat, ‘one of the boys would shout “Keb!” [meaning cabby, or conductor] and there would be a rush to see if the crowd was a likely one, i.e., good for a tip…’ The boys learned tales and poems to impress the visitors and were not afraid to exaggerate – ‘Didn’t we make them gape! And the yarns we spun for their benefit!’ They could earn substantial tips of up to half a sovereign or ten shillings – twenty times a boy seaman’s weekly wage.38

Victory with the Duke of Wellington in the background, c. 1896. The larger ship has open galleries on a form of elliptical stern, but both ships are still rigged.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Brass Foundry Album)

During the nineteenth century, Portsmouth developed as the county’s premier naval base. Unlike Chatham, it had direct and easy access to the open sea so it was good for experimental sailing, but it was also much closer to London than Plymouth. It was on the Queen’s route to her favourite English home, Osborne on the Isle of Wight. Portsmouth Harbour had the leading gunnery school in HMS Excellent and the premier torpedo and electrical establishment in Vernon, though the Plymouth and Chatham commands also set up their own schools in due course. Portsmouth was well situated for ceremonial events such as royal visits and fleet reviews, with the sheltered water of the Solent and many viewpoints on the mainland and the Isle of Wight. The Victory would see most of these events and play a part in many of them.

For twenty-one years after 1869, the Victory remained afloat, but increasingly obsolete and in poor condition. On The Navy List she was only one of five tenders to the Duke of Wellington, appearing after the old gunboats Ant and Medina, the former yacht Fire Queen and the ex-Post Office steamer Sprightly, none of which was more than a quarter of her size. She was under the command of Chief Boatswain William Guard in 1884, with four more boatswains as his assistants. She was a fixed point in a rapidly changing world, as new ideas in warship design followed one another in bewildering confusion. The revolving gun turret, first used in the USS Monitor in 1862, presented the ship designer with a dilemma, how to combine the topweight of sails and rigging while mounting the turret well above the waterline. Captain Cowper Coles tried to solve this with his Captain of 1870. The ship left Portsmouth in the summer of 1870 and soon sank in the Bay of Biscay with heavy loss of life – though this time the court martial was held in the Duke of Wellington rather than the Victory. She was followed by the Devastation, which kept the turrets but abandoned sail and was launched at Portsmouth in 1871. For nearly two decades, there was confusion in warship design as improved engines were fitted to give a reasonable range without the aid of sail, and guns and armour both developed in competition with one another. Beatrix Potter commented in 1884, ‘the Glatton is old for an ironclad, twelve years. It goes out for a few miles for target practice.’39

The Navy and the Public

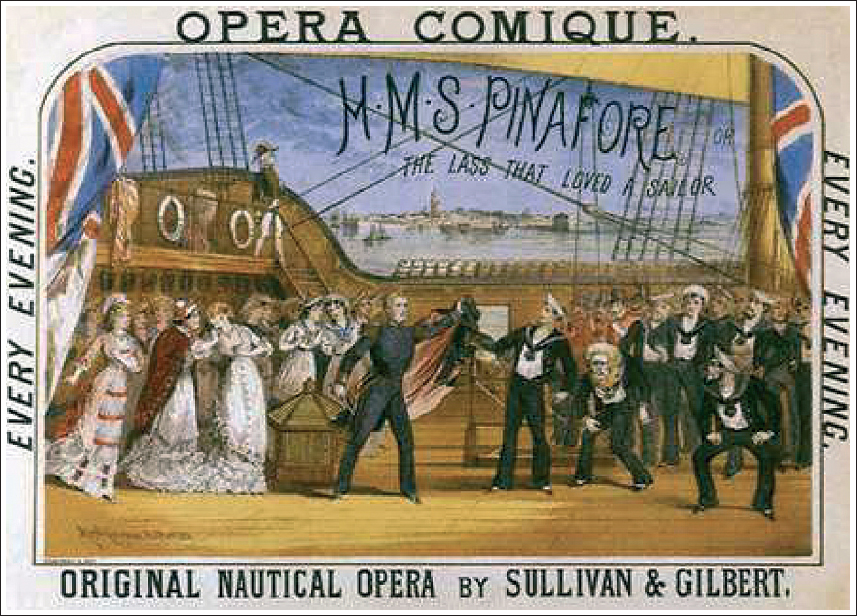

But, in some ways, the public image of the navy was still an old fashioned one. In 1878, while planning his light opera HMS Pinafore, W S Gilbert visited the Victory in Portsmouth Harbour to research the set design. Though the opera opens with the line ‘We sail the ocean blue’ there is no sign of the Pinafore leaving harbour during the action and she might as well be a depot ship like the Victory:

Victory at her moorings off Gosport, c.1895, again showing the semaphore tower in the dockyard.

(© Nadonal Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Brass Foundry Album)

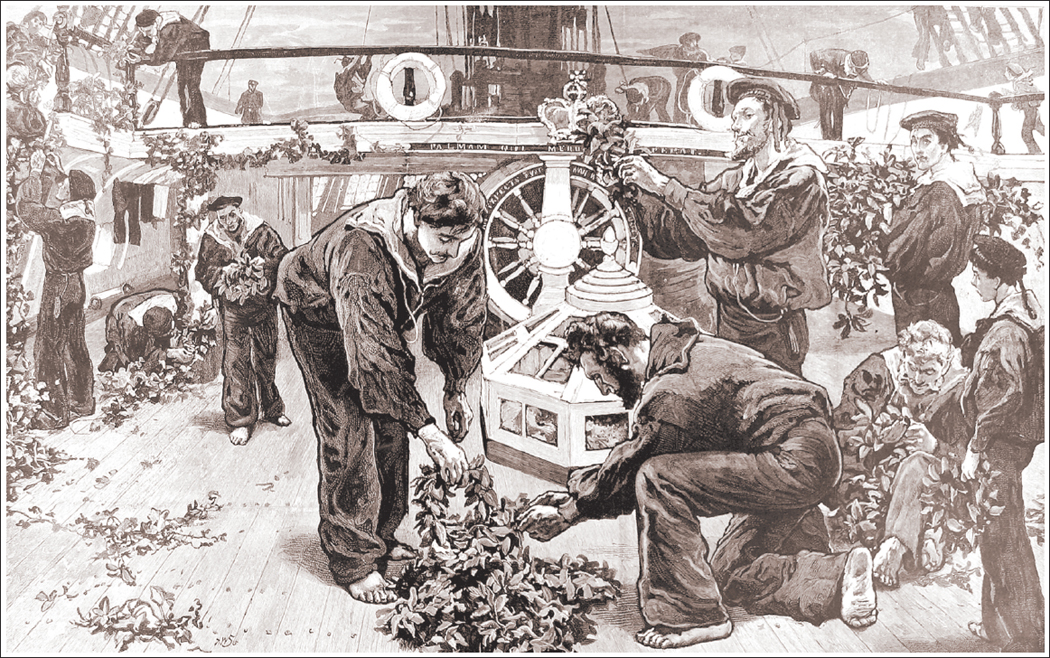

Sailors in the 1857 style naval uniform decorating the ship for Trafalgar Day, 1876.

(©Mary Evans, 10221390)

An original poster for HMS Pinafore, 1878. The uniforms are relatively modern but the ship is based on the Victory rather than any modern warship. Portsmouth can be seen in the background.

(Takenfrom East Norfolk Operatic Society, enosoc.co.uk)

Beatrix Potter with her father and brother.

(© The National Portrait Gallery, London, P1822)

The officers and sailors of the cast wore modern uniforms, which Gilbert had made in Portsmouth, and there is a satire on the current First Lord W H Smith:

Stick close to your desks and never go to sea,

And you all may be Rulers of the Queen’s Navee.

But the plot was based on nautical ballads and plays dating back to the last century. There is no mention of steam power or turret guns and, judging by the posters, the set reflected Gilbert’s research on the Victory. It was a breakthrough for the team of Gilbert and Sullivan, their first international hit.

Eighteen-year-old Beatrix Potter arrived in Portsmouth for a family visit in November 1884. It was many years before she would publish her famous children’s books, but her coded diary already showed imagination and whimsy. On arriving, she noted the ‘dirty old back streets, suggestive of the press gang.’ She was impressed with the physique of the sailors, ‘much sturdier and more sensibly dressed than the soldiers, except perhaps the Highlanders’, so it seemed that the navy’s recruitment policy was successful. She first saw the Victory from the shore through the mist, with the Duke of Wellington and St Vincent. She noted their high sides and thought, ‘How easy they must have been to hit!’ The next day, her father was approached by a ‘seafaring gentleman’ who persuaded them to take a boat tour and looked at his rivals ‘with the contemptuous air of a man who has made a conquest.’ They were taken down to the pier-head where ‘a broad, yellow-whiskered man… had brought round a large old boat resembling a tub.’ They were put in ‘as prisoners, not without difficulty owing to the swell from two or three of the small steamers and tugs which seem positively to swarm here.’ Her family showed some nervousness but young Beatrix ‘didn’t care tuppence for the water’ – instead, she was nervous about how she would climb the steep side of an old ship.

The atmosphere changed as soon as they left the shore. ‘When once we were fairly captured the naval gentleman suddenly relented and became very communicative, and took us [on] a very pleasant row to the Victory. I think this ship one of the most picturesque sights imaginable, particularly from close under the stairs – looking up at the queer little port-holes, and the end like a quaint carved old house.’ It was not hard to climb on board using a ladder, and soon they were on the ‘extraordinary long’ upper deck, ‘very clean and roomy, with very few coils of rope or furniture of any kind to cumber them.’ She saw the spot where Nelson fell and the boat which had borne his body during the funeral. She went below to see the original fore-topsail and the spot where it was believed that Nelson had died. She credited the well-known myth that ‘There is hardly any of the old Victory left, she has been so patched’ and her nautical terminology was not perfect – planks were ‘floor boards’ and at first she took the cabins down below for loose boxes – but she showed a good deal of insight when the tour continued to other ships in the harbour. The Duke of Wellington was now unseaworthy and the ironclad Glatton, out of date despite being only twelve years old, provided a total contrast. ‘We examined the revolving turret, very strongly plated, and with two guns which looked immense.’ Later, they visited the gunnery ship Excellent, which was ‘a striking contrast to the two other ships, being full of sailors.’ But she was most impressed with the troop transport Poona – ‘I never saw such an immense ship, we seemed as if we should never get to the other end.’40

But, around this time, Admiral Sir Edward Seymour was less enthusiastic about the Victory:

‘…A more rotten ship than she had become never probably flew the pennant. I could literally run my walking stick through her sides in many places, and her upper works were mostly covered by a waterproof coat of painted canvas.’41

However by the next century the ship was receiving 18,000 visitors a year, an average of about sixty per day excluding Sundays, though, of course, that would peak during the summer.

The Royal Naval Exhibition

Nelson and the Victory were raised in the public consciousness as naval history was used in support of greatly-expanded sea power. By 1889, Britain was worried about the rise of various medium-sized navies including Russia, Italy and Austria-Hungary – though as yet the newly-unified Germany did not figure on the list. The Naval Defence Act (1899) decreed that the Royal Navy should be big enough to cope with any two existing navies combined, and a programme of warship construction began. Around the same time, an American naval officer, Alfred Thayer Mahan, published his The Influence of Sea Power upon History and it had a widespread effect by showing that large navies were essential to national trade and development. In Britain, the Navy Records Society was founded to publish historical texts, in the belief that they could provide guidance for the future. Nelson was at the centre of this, and in 1899 G Barnett Smith wrote in Heroes:

In the Glory-roll of British heroes no name exercises such a strange fascination as that of Horatio Nelson. The record of his deeds stirs the most sluggish blood and makes the Anglo-Saxon proud of his name and race. He is the boy’s hero and the man’s hero, from the time when he first steps forth on the human stage to the sublime moment at the Battle of Trafalgar.

Although the location has recently been challenged, the position of the knee against which Nelson died has been marked for some considerable time, as shown in this 1889 print by Barrett.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London PAD5973)

This was celebrated in a huge exhibition featuring 5,374 objects in 1891. Originally, it had been planned to hold it at Greenwich and tow the Victory there, but the site was changed to Chelsea and there was no question of taking the ship through the numerous bridges of London – in any case, there would be great risk in taking such an old ship to sea. Instead, a full-sized ‘model’ or replica was commissioned from the exhibition designers Campbell, Smith and Co. It was ‘perfect as regards the outside, from the water-line to the bulwarks, with hammock nettings, &c., showing the bow with the old figure-head…’ However, the local authority had refused permission to fit full masts and rigging. On entering through a port in the side, a visitor would arrive on the middle deck then go down to the lower deck, which was fitted with guns as at Trafalgar, run-out on the port side and stowed on the starboard, with mess tables and hammocks in place.

The exhibition was a great success, attracting more than 2.3 million visitors. Apart from the British Royal Family, the most distinguished visitor was Kaiser Wilhelm II, making a state visit three years after his accession to the German throne. He did not spend much time with the Victory replica, but his wife the Kaiserin did. It was perhaps on this occasion that he was presented with a desk made from the timbers of the Victory, produced by the high-class furniture makers Waring and Gillow. It is not known how much influence this had on his decision to build a great navy for Germany at the end of the decade. When the exhibition was over, the Victory replica was sold to the Isle of Man for £150 and set up there.

Signal School

Meanwhile, the Victory herself found a new role. With the advent of fast steamships and development of electric lamps, signalling became more important than ever to the navy and needed increased training. The flagship Duke of Wellington was considered unsuitable in view of ‘the incessant and unavoidable noise…. Occasioned by the various drills being carried out.’ As Signal Boatswain Henry Eason later recorded:

At the latter end of the year 1889 HMS Victory was fitted up as a Naval School of Telegraphy. The instruments set up in the Admiral’s after cabin were Sounders, Bells, Needles and Printers…. Manoeuvring signals were made and models worked, and everything such as turning flags etc.. carried out the same as it would be in a fleet at sea…. Fog-horns were also practised, men being posted round the deck each with a police whistle, and treated as a single ship, flagships and leaders being denoted, signals being made as in a fog, being answered or repeated according to instructions… Flashing signals were carried out on the orlop deck of the Victory, and two large Semaphores were in position for instructional purposes, one being set up in the [k]night-heads and the other on the poop.42

The next step was to develop wireless telegraphy and the Royal Navy was very advanced in this, with experiments by Captain Henry Jackson as well as close collaboration with Marconi. But in Portsmouth that work was carried out from HMS Vernon, the torpedo school, presumably because the torpedo branch provided the navy’s electrical expertise, and because it was situated closer to the shore and electric power. In 1906 a signal school was set up in the naval barracks, and the Victory would have to find yet another role.

The navy had finally found money to build shore barracks, by means of the Naval Works Act of 1891. The Portsmouth buildings opened in 1903 and ‘The hulks were vacated with no ceremony or regret as they were unpleasant and miserable quarters.’ The men paraded into their new quarters to the sound of bugles and drums, watched by a large crowd, but the Victory was not forgotten. Men were only subject to naval discipline if they were attached to ships and vessels of the fleet, and those in Portsmouth were nominally part of the crew of the yacht Fire Queen, though in December the King directed that men in the barracks should wear the cap ribbon ‘HMS Victory.’ Early in 1905 the commander-in-chief reported that there was a ‘strong local feeling’ that they should be formally attached to the Victory – her name was world famous, that of the Fire Queen had ‘little connection with the service’. This was agreed and the practice would continue until 1974, so many thousands of sailors wore the cap ribbon Victory, however briefly, and in most cases they never visited the ship herself. In 1905 the officers borne on her books included Admiral Sir Archibald Douglas and his staff, more than eighty officers of various branches to run the ‘general depot’ or barracks, twenty more ‘for Portsmouth dockyard’, four instructors and seven trainees of the School of Gymnasia, two dozen attached to the signal school (including one ‘fortrainingofhomingpigeons’), five for fleet coaling duties, three for workshops, five for training boy artificers and thirty-nine for miscellaneous duties.43

The full-size ‘model’ of the Victory in the grounds of the Royal Naval Exhibition at Chelsea.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, P47508)

Rammed

In October 1903, Christopher Arnold-Foster was a cadet in the new naval college at Osborne, just across the Solent on the Isle of Wight, doing sea time in the sloop Racer in the Solent. He was well connected as the son of a government minister, and ‘played battle’ with the Misses Fisher, daughters of the commander-in-chief at Portsmouth – though it was ‘not a ferocious or violent game’, he told his mother. He was on deck when the old battleship Neptune of 1874 was being towed to the breaker’s yard by the German tug Roland. The tide was strong and when the tug turned the Neptune did not follow. She headed for the brig Seafower but her ram went under her hull and did little damage. The Neptune drifted across the harbour, while the captain of the Racer ordered the cadets into boats. The hawser broke and she began to drift towards the Victory, where it was seen by another party.

Amongst my class of Cadets… was an extremely pious parson’s son who very properly objected to us using bad language. When it appeared certain that the Neptune would ram our old ship and probably sink her, he burst forth excitedly, ‘We are all going to be drowned; Now is the time to swear. Damn the Devil!’, which considerably relieved the tension and made us all laugh.44

As the Neptune struck, Arnold-Foster ‘could easily hear the timbers of the Victory breaking, and for some minutes the captain thought she would sink.’ All the ships sent collision mats to stop the leak and the old ship was towed into dry dock for emergency repair, after sinking several feet.

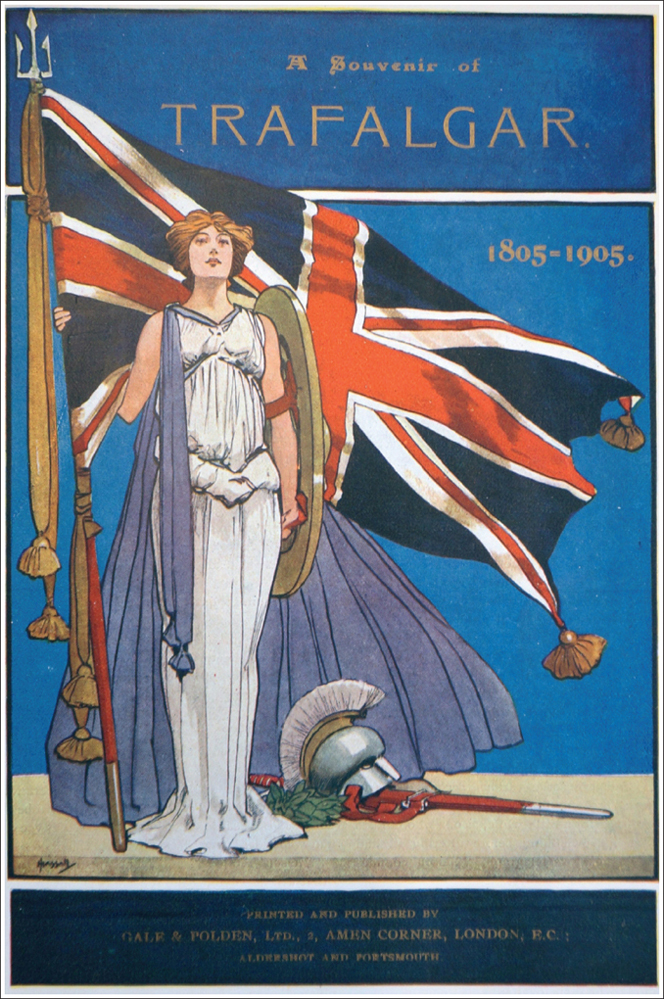

Two years later was the centenary of Trafalgar, though celebrations were restricted in order not to annoy the French, with whom the government had recently entered the Entente Cordiale. Royal Family and government officials were not involved, indeed the Prince of Wales had set off on an empire-voyage just two days earlier. But it was celebrated in many other ways, including the Victory which was decorated with evergreen at the mastheads and wreaths hanging between the masts and on the spot where Nelson fell. At night it was lit up with electric lights forming the outline of the hull, the rigging and the gunports, with Nelson’s flag formed in lights at the masthead. To the Illustrated London News, it was ‘the most picturesque of the Nelson celebrations.’ At a dinner on board the ship, Admiral Sir Cyprian Bridge spoke on ‘Trafalgar and its Effects on History.’ He began, according to the Times correspondent ‘The celebrations of the centenary were of a popular and spontaneous character; the government, wisely, as he thought, were leaving them to the people themselves.’ He paid a subtle tribute to old enemies and new friends – ‘…one of the things that made Nelson great was the greatness of those with whom he had to contend.’45

Meanwhile, the father of Arnold-Foster’s lady companions, Admiral Sir John Fisher, had become First Sea Lord. He abolished sail training and was unsentimental about the Victory – she was listed among forty vessels, ‘[as] utterly useless for fighting purposes – Depot Ships’.46 One of his many reforms was to build a revolutionary new battleship on Number Five Slip at Portsmouth, less than a mile from the Victory on her moorings at Gosport. The Dreadnought was fitted with an all-big gun armament to outfight any ship on the oceans, and the new turbine engines to outrun them if needed. She heralded a new age in naval warfare and for the next decade or more the naval powers would measure their strength in Dreadnought battleships. She also opened up the arms race with the growing naval power of Germany, which increased tensions between the two countries. Her launch on 10 February 1906 was also slightly muted, if only because the Queen’s father, the King of Denmark, had recently died. But it ‘appealed to the popular imagination in a very exceptional degree’ and extra police had to be drafted from London to control the crowd. The Times correspondent noted, ‘the continuity of British naval history’ to be seen around him. ‘Here, first and foremost, always noted with loving recognition and affectionate solicitude, is Nelson’s Victory. At a little distance is the St. Vincent, another example of the wooden wall of Old England.’ There were several Royal and naval yachts of different ages, plus, ‘the Colossus, the Barfleur, the Drake, and half-a-dozen other vessels of modern construction. And, finally, here is the Dreadnought ready to join them, the latest expression of thought and experience in the domain of naval architecture.’

The old ironclad Neptune collides with the Victory in 1903.

(©IMDB, tt2824818)

Events on Board

Frank Wiseman was a teenage Domestic 3rd-Class, at the very bottom of the naval hierarchy, perhaps because his short-sightedness prevented him becoming a seaman. He was expected to bring breakfast into the warrant officers’ mess at 8.30am on 5 March 1906 but did not appear. Instead, it seems, the ‘inquisitive lad’ had climbed up in the pantry port, as was his custom, to see a passing ship. It seems that he fell out, and his cries might have been drowned by the noise of riveters working on the ship’s boiler. As he could not swim, he was never seen again despite a search of the area by boat.

During her century in harbour, the Victory spent time as a training ship for officers, seaman, boys and signallers. She usually had Royal Marines as part of her complement, as well as domestics and writers, or clerks. With no engines and very little modern machinery, she saw very little of the other great naval tribe, the stokers. Their numbers were expanding rapidly during the early 1900s, as the new fleet of Dreadnoughts and battle-cruisers needed vast numbers of them to feed their engines with coal. Physical strength was important and they were recruited as adults rather than boys, but they did not have the rigorous training and esprit de corps of the Royal Marines, so stokers often presented a disciplinary problem. That was why eleven of them came on board the Victory as prisoners in November 1906. At the beginning of the month, Lieutenant Bernard Collard, an Excellent-trained gunnery officer, objected to the ill-discipline of a group of stokers on the parade ground in the barracks. He gave the order ‘on the knee’, which he claimed was merely to allow the men in the rear ranks to look over the heads of the front rank, but was seen as a deliberate humiliation by the stokers. It might have passed over but that night the seamen taunted the stokers with a cry of ‘on the knee’. The canteen was smashed up and rioting spread to the townspeople over the next few days, with marines being called to restore order.

Eleven alleged ringleaders were tried on board Victory at the end of the month. Among them was Edward Allen Moody, twenty-three years old and eighteen months in the navy, with a poor disciplinary record, charged on three counts. There was no real evidence that he had taken part in the original incident, but it was testified that he had incited the men with the words, ‘You call yourself men; directly an officer speaks to you, you salutes the fucker and then goes and turns in; stick together if you are going to.’ He claimed he had tried to pacify the men but the court believed that ‘he was a man of considerable influence with the rest of the men, pacifying or inflaming them as the fancy took him at the moment.’ When he was sentenced to five years in Wormwood Scrubs, there was outrage, especially in the growing labour movement, for many stokers had links to the trade unions, and Moody himself was a former carter. Portsmouth United Trades and Labour Council claimed the sentence was ‘out of all bounds of justice.’ It was not helped when Collard was tried on board the Victory. He was cleared of two charges relating to the incident in November, but guilty of a previous incident when he had ordered Stoker Albert Acton ‘on the knee’, and reprimanded him. It was never established whether he used the phrase ‘on the knee, you dirty dog’, but popular legend believed he did and it represented the attitude of many officers to the lower deck. His career did not suffer however, he eventually reached the rank of rear-admiral where he fell foul of another highly-publicised court martial. Moody’s sentence was reduced to three years, while several of the officers in charge of the barracks were removed from their posts for allowing the situation to get out of hand.

A programme of events commemorating the centenary of Trafalgar in 1905.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, SNR/7/2)

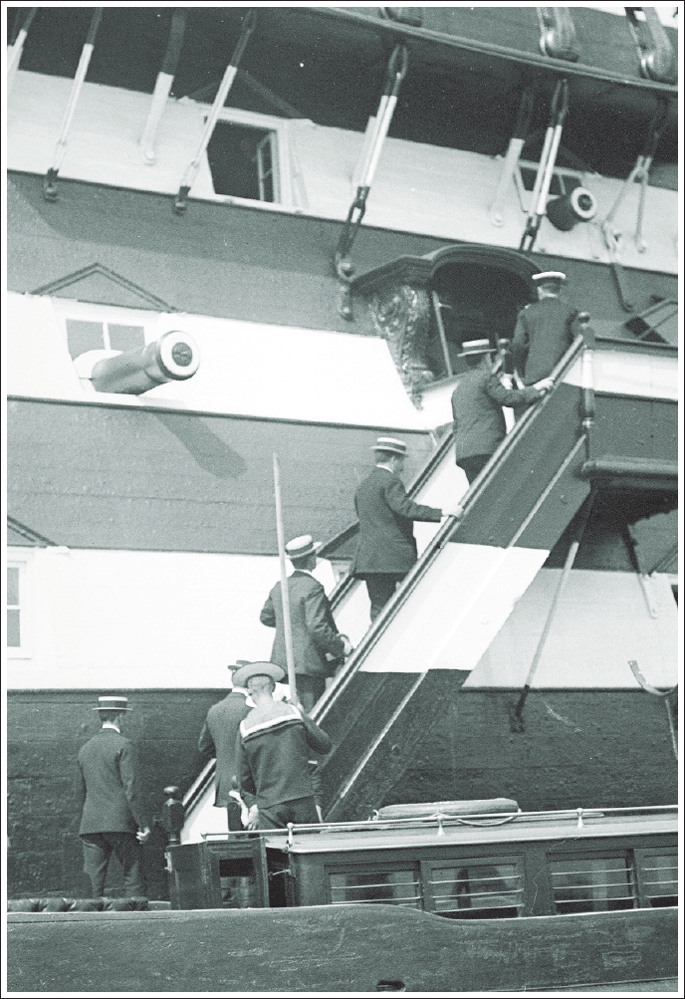

Witnesses arriving for a court martial in 1909 after HMS Gladiator was in collision with the American ship St Paul. Captain Lumsden of the Royal Navy was reprimanded over the affair, though most of the blame went to the St Paul.

(© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Brass Foundry Album)

The desk on which Kaiser Wilhelm II signed the order to mobilise the German Army in August 1914, setting off a chain of events which led to European war.

(Photo from Potsdam, Germany, Stftung Preussische Schlosser und Garten)

The Great War

The reserves of the Royal Navy happened to be mobilised for a test run in July 1914 as events in Europe began to move towards war. A great fleet of fifty-nine battleships, old and new, plus supporting vessels was already assembled off Portsmouth and Winston Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, ordered them to be kept in service. The Victory had already played a key, if unrecognised, role in perhaps the most momentous event of the nineteenth century – Napoleon’s campaign against Russia. Her timbers, if not the ship herself, were to have a passive and indirect part in perhaps the greatest turning point of the twentieth century. On 1 August 1914, according to the diary of Field Marshal Erich von Falkenhayn, Kaiser Wilhem II of Germany signed the order to mobilise his army, shaking the field marshal’s hand with tears in his eyes. This was the trigger which set the German plan into motion, involving the invasion of Belgium and war with France, Russia and Great Britain and their respective empires. It was almost as devastating as the mythical ‘button’ which leaders were expected to push to start a nuclear war in the latter part of the century, as most of the nations of Europe were drawn into a war which would kill millions of them. He signed the order on a desk said to have been made from the timbers of the Victory, crafted by the firm of Waring & Gillow and presumably presented in the 1890s, when relations between the countries were much better.47