2

Go-Betweens in the Great War

In September 1914 the Bavarian aristocrat Prince zu Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg wrote a depressed letter from the front: ‘the economic losses of this war will be enormous. It is as if a brewery owner picks a quarrel with a pub-owner and then kills him. He has won the fight, but nobody will be left to buy his beer.’1 Such a rational verdict was only the more impressive since Löwenstein had been a friend of the murdered Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

He was also a friend of the English Duke of Portland, who had a similar opinion: ‘The outlook is very bleak and Europe will not recover from this for two generations.’2 Portland had relatives in the Netherlands and Germany. For him the war also meant that he had to cut off links with many of them.

Ideally royal and aristocratic families worked like a closed ecosystem. However, the ecosystem could get out of balance when separate elements broke off. Three main threats endangered the equilibrium: first biological failure (no male descendants); second, financial failure (bad investments); and third, unpredictable outside threats like revolutions, coups, or wars. This last threat appeared in 1914. Until then there were not many reasons to cut oneself off from the international network. It was literally a safety net. Up to 1914 it had also been in the interest of aristocratic families to extend their international contacts. The image of a wide family tree held its appeal. They were proud of the age of their tree—the older the better. But they were even keener that branches were ‘growing’ into different neighbourhoods, i.e. countries. The more branches abroad, the grander the family had become. It was blooming.

However, this was not a picture that appealed to ardent nationalists. A tree trunk that spread its branches into foreign territory was suspected of being rotten, diseased. It had to be axed to fit national demands. In August 1914 the question for international families therefore was, did kinship rank before national loyalty? Up to this point it had been possible to juggle both.

Identities are not like hats: one can wear more than one at the same time.3 European aristocrats had always done this. Increasingly, however, they encountered difficulties. They were truly international and therefore regarded as unpatriotic. Already in nineteenth-century Britain, the Queen’s husband Prince Albert was repeatedly attacked for his German background and had his loyalties questioned. In Germany, criticism of dynasties and the higher aristocracy was even broader and fiercer. Here it was not just the German middle classes who attacked the higher aristocracy, but lower German nobles joined in too. They themselves rarely had international connections and resented the rich ‘grand seigneurs’. The extreme nationalist and anti-Semitic historian Heinrich von Treitschke was one such critic.4 In his eyes many members of the higher aristocracy were cultivating their English connections too much which in turn westernized them. Treitschke was not alone in fearing conflicts of loyalty, even potential treason. The German Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow criticized the higher aristocracy in Germany for their ‘cosy’ closeness to their ‘foreign relatives’. The insinuation was that this closeness had resulted in them becoming politically unreliable. Bülow himself was married to an Italian noble and hypocritical to the core, but he absorbed the Zeitgeist. The Deutsche Adelsblatt (a German paper for the nobility) declared it as its major aim to create a homogeneous, national German nobility. International aristocrats no longer fitted into this concept.

By the end of the nineteenth century German aristocrats were therefore confronted with two threatening new movements: nationalism and democracy. Both seemed alien to them. As Prince Rohan explained in 1929, his peer group had to make a choice since opposing both movements seemed impossible:

The formation of nationhood was naturally anti-aristocratic, it was the victory of the modern against the medieval world. Along with the national, the democratic idea, the older brother of the national, won power over Europe. The nobility faced the choice of siding with national or with democratic ideas. Since both had risen in the fight against the nobility, it had chosen the one that was easiest to adapt to its traditions.5

In other words aristocrats had to react pragmatically: Because the threat of democracy was so much greater—nationalism was the lesser evil. Prince Rohan would take nationalism to its greatest extreme and become a dedicated Nazi.

Since many members of the higher aristocracy were international in their roots and way of life, they had to indigenize and sell themselves as home grown ‘natives’. This was far from easy. Marie von Bunsen, for example, fretted about her ‘double’ identity for years. In the 1930s she described how much it had weighed her down: ‘since my childhood I have clearly seen the disadvantages of my extraordinary existence. Later I fought internally against my double nationality and got it under control. I tried, without losing the values of England, to gain the calm, firm line of the German national community (Volksgemeinschaft).’6

A further problem was that aristocrats did not fit the racial categories. This had already started during the nineteenth century when racial theories and the idea of ‘pure’ blood began to circulate. Similar to the genome today, blood was used as an overriding explanation for human behaviour. It also developed a metaphysical meaning: there were things that one had had for ‘generations in the blood’ and predestined one for one’s station in life.

The Queen of Romania, for example, wrote about herself and her sisters (Figure 3): ‘we were a strong race—the mixture of Russian and English was a strange blend, setting us somewhat apart from others, as, having strong and dominating characters we could not follow, only lead.’7 Others would not have agreed with such a positive interpretation. Their blood analysis of the higher aristocracy was far less benevolent. According to purists the ‘international blood’ which was common in dynasties and the higher aristocracy transferred negative qualities. Being ‘mongrels’, whether dogs or human beings, implied imperfection.

Figure 3. Four Coburg sisters who would be divided by the First World War: Princess Beatrice (Spain), Princess Victoria Melita (Russia), Princess Alexandra (Germany), and Crown Princess Marie of Romania in 1900.

In Germany the mixed blood issue was combined by critics of the aristocracy with the old argument of their immoral behaviour. A Cologne newspaper, for example, reported in 1916 in great detail about the chaos in an ‘international aristocratic home’.8 A divorced American, a Miss Gould, had chosen to marry the Duke of Talleyrand-Périgord. Their resulting son would have been the heir to the Silesian property of his father. But because the dissolution of the first marriage of his mother had not been recognized by the Catholic Church, the son was seen as illegitimate. The journalist used this story to analyse the pedigrees of everyone involved. The divorced American lady got surprisingly high marks because her father had started off as a hard-working miner who had made his fortune by honest means. The aristocratic son-in-law Talleyrand-Périgord, however, was portrayed as a scoundrel who was frequently sent off by his family to countries ‘where the ground was less hot than in France’. Because of his bad reputation, even his Silesian peer group refused to receive him. His son on the other hand offered hope for improvement and was recognized by the Silesian magnates. The main point of the article was not that the ‘illegitimacy’ of the boy was the problem. What was seen as shocking in 1916 was the fact that he and his immoral father were ‘sujets mixtes’, French-Germans who were allowed to live in both nations. Such ‘sujets mixtes’, were according to the newspaper:

more common among the aristocracy than one realizes. With the strong national antagonism that has surfaced in the current war, legal questions about property held beyond borders will become even more acute. In their various homelands these mixed people will feel alien and won’t fit in with the mores of their environment. This appears even less desirable with highly born people because … the well being of their subjects depends on them.9

Suspicion towards cosmopolitan families was of course not just a British or German phenomenon and it was not just focused on the aristocracy. It went beyond class barriers. This became evident when war broke out. The Viennese writer Karl Kraus famously captured the jingoism that gripped Austria-Hungary in 1914 in his novel The Last Days of Mankind.10 Similar outbreaks were recorded all over Europe. In Berlin, London, and Paris, foreigners were attacked on the streets. Families that had been naturalized for generations were suddenly under suspicion and proud old names became a liability. From France, the British ambassador Sir Frances Bertie reported that Princess Frederica of Hanover had been attacked at Biarritz because of her German sounding title. That she was a member of the British royal family was known only to genealogists; the average Frenchman did not care about such details.11

On the other side of the ‘trenches’ in Germany, the Dowager Duchess of Coburg did not dare to leave her apartments because she had been called a ‘Russian spy’ by angry Germans. In fact, it was even more confusing as she had changed her nationality twice. Born a Russian, she had married Queen Victoria’s second son Alfred and become British. Once Alfred succeeded to the Dukedom of Coburg, she had turned into a German.

The Grand Duke of Hesse suffered from the same ‘burden’. He was a German sovereign but close to his sister Alexandra, Tsarina of Russia, and his cousin the British King George V. Added to this, his residence, the little town of Darmstadt, was in the summer of 1914 full of Russian students who were now a major target. Most of them left just in time, but the angry Darmstädters went out on a witchhunt anyway, suspecting everyone of spying for Russia and even searching under nuns’ habits. Also rumours circulated that cars were transporting gold from France via Germany to Russia, so every car in Darmstadt was being stopped by the Grand Duke’s suspicious subjects.12

The Grand Duke was not at home at the time and returned immediately to restore some kind of order. In fact the outbreak of the war had caught many aristocrats on their holidays abroad. The British born Princess Daisy Pless was visiting relatives in England in the summer of 1914. Her German husband ordered the chauffeur to return but did not ask his wife to come home as well. She felt rather hurt about this oversight. The couple had been estranged for some time but Prince Pless tried to apologize in a clumsy way:

I know that you are a good German in regard to your wish that we will win this war, because the future of your sons depends on it. But despite all this you will suffer from the tragedy which is looming over your old country and from which all your relatives and friends will suffer. There is no doubt that the war between England and Germany will be fought to the bitter end, and even you can only hope that the English will be vanquished decisively.13

Princess Pless could not follow her husband’s argument. She returned to Germany but remained unhappy. In her memoirs she described her frustration:

I had relatives and dear friends in England, Germany, Austria, Hungary, France, Spain, Russia, Sweden … How selfless they were, how well these best elements of the fighting nations knew each other and despite this, they had to continue killing each other.14

Prince Max von Baden, later Chancellor of Germany, empathized with her. In 1916 he wrote to Daisy Pless:

I pity all these people who haven’t been born in the country in which they live and now belong to one of the belligerent nations. It is a hard fate, especially during the war, which brings out all the bad emotions. Since my mother was Russian I can understand this especially.15

Baden did not mention to Daisy that he used his international contacts for clandestine negotiations. As will be shown later these negotiations were far from benign.

Thus birth into a ‘multinational family’ met a reversal of fortunes, became troublesome, even dangerous. This was particularly the case for aristocrats who were more visible than any other social group. After all their glamorous social engagements and international connections had been covered in the press over many years.

They soon realized they had to act if they did not want to be swallowed up by a wave of nationalism. To demonstrate loyalty seemed easier for aristocratic men than for women. Men could just put on a uniform which clearly demonstrated which country they belonged to. But even this simple act became a matter of soul searching. Some men simply did not know which army they should serve in. Even members of the famous military von Moltke family were slightly confused: ‘Count Moltke, the Danish envoy in Berlin, had once served for a short time in the French army and was therefore distrusted by the Germans.’16

The aristocratic Bentincks, a Dutch, English, and German family, seriously believed that they could continue their commuting between the countries concerned. The German officer Wilhelm Bentinck, born in the Netherlands, asked Kaiser Wilhelm II not to have to fight against England, where most of his relatives lived. When this was denied Bentinck retired and returned to Holland. His Anglophile sister Victoria supported his decision: ‘Some blame him for this … personally I am glad he acted in this way.’17 She spent the war in Britain, but not all Bentincks decided on a pro-British stance. Some had not forgotten that the German Kaiser had graciously visited their Dutch family seat Middachten in 1909. One Bentinck daughter was married to Rudolphe Frederic van Heeckeren van Wassenaer (1858–1936) who sympathized with the Central Powers and even published a pro-German newspaper in Holland. Another Bentinck would in 1918 offer his home to the exiled Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Other international families also had trouble choosing an army. Queen Victoria had financed her German relatives the Leiningens for several generations. Now they joined the German army. Prince Emich Leiningen, born in Osborne House and socialized in England, got into a bizarre situation. He looked English and when he occupied a French village in 1914 the villagers took him for an Englishman. Leiningen felt deeply uncomfortable: ‘I told them that I had been born in England but wasn’t sure whether I was still English.’18 For him this wasn’t just a legal, but also an emotional question. Even though he would distance himself from his English side during the war, he thought it could still come in handy. To his soldier-son he wrote in 1917: ‘If the English get you, don’t forget that your grandfather was a British Admiral, they might treat you better then.’19

Yet once these aristocrats had decided on a uniform they had to prove that this was not some kind of camouflage. Pure mimicry was not sufficient. A full metamorphosis was expected of them. Aristocratic women tried to help. They did their best to prove themselves by focusing on medical and charitable fields. This had been an old tradition for the aristocracy and always brought popularity. Amongst many aristocratic women there started a real race to prove themselves the leading Florence Nightingale. The competition was fierce: the bigger your hospital, the better. In Germany they particularly fought over Red Cross medals; everyone wanted to receive the new status symbol. The role model for hospital work was the royal houses, whose members visited the wounded. In Britain this was famously demonstrated by the King and Queen, who embarked on endless hospital visits. It was far from easy for them. Queen Mary simply did not like sick people. Her relative Maria of Romania, who thought of herself as a competent nurse, was quite scathing on this point: ‘Although she [Queen Mary] hates illness she is very kind to the sick and pays them stiff little visits and always sends messages of enquiry.’20 Maria of Romania thought that overall the British royal couple did a pretty good job nonetheless: ‘He [King George V] and she worked in such harmony. They were like a splendidly paired couple of first-class carriage horses, stepping exactly alike.’21

In spite of these good works, suspicion was not dispelled. Demonstrating commitment to the war effort was not enough.

Despite her charity work, the British/German Daisy Pless became a target. In 1916 her husband informed her that he had done his best to defend her reputation:

A newspaper reported that on your birthday we had raised the English colours; it had to apologise. It was just the colours of the Wests [Daisy’s British family] red and blue, which some idiot took for the English flag.22

The Pless family sued the newspaper. But Daisy’s problems seemed relatively minor compared to the Duke of Coburg’s.

Since his wartime experiences are essential for understanding how he developed into a go-between for Hitler, a brief look at his case will be illustrative. Coburg had spent the run-up to the war in England. On 28 June 1914 he was visiting his sister in London when he first heard about the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Though it did not seem urgent at this point, he decided to return to Germany. Carl Eduard now lived in the castles of his ancestor Ernst II Duke of Coburg, who had once written that the secret motto of the Coburg family should be ‘one for all and all for one’. But such a thought seemed to be outdated.

In retrospect Carl Eduard saw the events of August 1914 as the greatest disaster of his life. After the war he wrote to his sister Alice: ‘the last time we parted [with] you going to Canada, the awful war broke out, breaking our happiness.’23 Up to this point he had commuted effortlessly between Britain and Germany, paying visits to the royal family at Sandringham and the Kaiser in Berlin. Yet pleasing both camps was no longer possible. According to his sister Alice’s memoirs, the war ‘shattered his life, for he was denounced in Germany for being English and in England for being German. He told me once that had it not been for his wife and family he would have returned to England, had it been possible. He had to serve in the army, but refused to fight against England and was posted to the Russian front.’24

As usual, Alice was being economical with the truth. Coburg had two lives—a placid one before the war and a criminal one after the First World War.

Her recollection that he was sent to the Russian front is also incorrect. He was more or a less a chocolate soldier, who spent most of his time dining at various casinos behind the front and visiting ‘his’ Coburg troops. These trips were camouflaged as ‘research trips’ and always followed the same pattern. The VIP guests were shown around a trench, photos were taken, short conversations with a few ‘ordinary soldiers’ arranged, followed by dinner with the highest ranking officers. The next morning medals were handed out. Carl Eduard, always an ardent traveller, enjoyed these trips and decorated many a soldier. Unlike his relative the Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse, Carl Eduard never felt any shame about this ornamental role. Hesse would later accuse his dynastic peer group of using the war more or less as a series of sightseeing trips—either visiting each other or the cities Germany had just occupied. Ernst Hesse felt ashamed of this voyeurism. When he met soldiers who had experienced combat, it ‘made one feel very small’.25

Carl Eduard was not known for any such reflections. He also did not hesitate when it came to publicly distancing himself from his British relatives. This was an episode his sister Alice naturally did not mention in her memoirs. For Carl Eduard it was simply a priority to assure the survival of the German branch of the House of Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha. In 1914 he had announced: ‘I hereby publicly declare that I have renounced my position as chief of the Seaforth-Highlanders regiment, because I cannot be … in charge of a regiment which belongs to a country that has attacked us in the most despicable way’ (‘dessen Land uns in schändlicher Weise überfallen hat’).26

In March 1917 he went a step further and signed a bill declaring that ‘members of the House of Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha who belong to foreign nations will lose the right of succession if their country is at war with Germany’. His advisers had phrased the document carefully. They could not exclude all ‘foreign’ members of the house because the King of Bulgaria was a Coburger—and Bulgaria was a German ally. However, the bill was a slap in the face for the British, Belgian, and Portuguese relatives. It also showed Carl Eduard’s complete disregard for the dynastic principles he was reared in (and which he would five years later simply revert to when they became useful again). Furthermore it demonstrated indifference to his closest relative. His mother was living in London during the war and had every reason to fear reprisals. Like so many royal German relatives, she was taken in by Queen Mary and therefore elegantly removed from the public eye. Carl Eduard’s sister does not mention the event at all in her memoirs. Instead she focuses on the way the British royals changed their names in July 1917. She was now turned from a Teck into a Countess of Athlone. For Alice this was an unwelcome imposition: ‘Granpa [her husband] was furious, as he thought that kind of camouflage stupid and petty.’27

Alice does not elaborate on this point, though it would have been interesting to know what exactly she felt had to be camouflaged. George V certainly had every reason to change the family name. On 13 June 1917 German planes had attacked London and killed 160 people. Anti-German feelings were stronger than ever before.

Because of George V’s ‘Titles Deprivation Act’ of 1917 and the confirmation of it in 1919, Carl Eduard lost the title Duke of Albany and all rights to the dukedom of Albany and other territories attached to the title. He was officially a traitor peer. His immediate reactions to this are unknown. It was not just the British connection that he had lost, his old mentor, the Kaiser, was also no comfort. Wilhelm II had been sidelined from the beginning of the war. After General von Moltke’s nervous breakdown and General Falkenhayn’s dismissal two new leaders emerged—Hindenburg and Ludendorff. Though Carl Eduard joined the Bund der Kaisertreuen (the Kaiser Loyalists Club) to demonstrate his allegiance to Wilhelm II, he was fully aware of Wilhelm’s impotence and preferred Hindenburg. The admiration for Hindenburg crossed social and religious divides. Even Catholics developed the belief that this Protestant warrior could save Germany. Though Carl Eduard was unwell for periods of the war, the weaker he became physically, the tougher his political views were. For a while Hindenburg was his favourite but, as we will see later, he would soon be interested in much more radical options.

While Carl Eduard became an eager go-between in the inter-war years, he did not play such a role in the First World War. But other families with international connections were interested in such work. They wanted to turn their ‘hybrid’ background to advantage. This made sense at a time when official diplomatic relations between enemy states had ended. With the outbreak of war embassies had been closed down and a diplomatic blackout ensued. Representatives of neutral states were now employed to communicate on the most urgent issues between enemy countries. Yet they could not be trusted completely. They had to follow their own national interests and had to be careful not to endanger their country’s neutrality. This diplomatic vacuum made the use of go-betweens a matter of urgency.

Prince Fürstenberg’s mission

Fürstenberg was enormously satisfied that Germany had stood by its alliance partner Austria-Hungary. It was everything a good go-between could hope for. Yet, with the outbreak of war his grip on Wilhelm II started to slip. This flabbergasted Fürstenberg who had hoped to play a key liaison role between the two countries. He also had expected to join the Kaiser at army headquarters. On 3 August he wrote in his diary:

Audience with SM [Wilhelm II] who was so touchingly nice, but on Plessen’s advice he does not want me at headquarters! It was a tough moment. He embraced me repeatedly.28

The Kaiser seemed to realize how upset his old friend was and sent him a warm telegram a few days later:

In the spirit of our old friendship, I shake your hand. Even though duty separates us during these hard times, everything remains the same between us. Good bye in better times!29

Hans Georg von Plessen, who was running the imperial headquarters, had cunningly told the Kaiser that for Fürstenberg surely ‘the Austrian army was closer to his heart’. An invisible cordon sanitaire had been drawn around Wilhelm. To have an influential Austrian near the Kaiser was the last thing the courtiers and the German military wanted. From now on Wilhelm was shielded from the more unpleasant aspects of the war. The Kaiser’s cousin, the Grand Duke of Hesse, later claimed that this was a mistake, that Wilhelm should have been forced to face the realities of the situation. But the Kaiser’s mental state was already unbalanced. The man who had loved indulging in war games found reality unbearable.

Following Plessen’s advice, the disappointed Fürstenberg joined the Austrian army, pretending not to care about the imperial snub. Always the bon vivant, he recovered quickly. His work for the Austro-German Alliance remained paramount and he hoped that eventually he would be able to continue it. His go-between work had always been driven by economic and political motives but by now it had also become an emotional concern. Among his papers he kept a sentimental poem from 1915:

In all countries it will be admired in days to come:

Alone two brothers stood, with the world at war.

And while cities were burning and sank day by day,

the brothers did not separate but stood firm,

And fought without regret and treachery

The Nibelungen-fidelity became reality!

Over the following years, the meaning of almost every line of this poem would be reversed.

Fürstenberg had welcomed the war enthusiastically and he certainly enjoyed the fighting. The adrenalin rush reminded him of his favourite sport—hunting. During these first months in the field he wrote home cheerful letters full of hunting metaphors. Yet the cheerfulness eventually subsided. By 1915 he had realized how badly the Austro-Hungarian military was doing in comparison with its German ally. This unevenness on the battlefield also had a negative effect on Austro-German diplomatic relations. The feelings of brotherhood Fürstenberg had hoped for had always been a fantasy. With the stresses of war, the artificiality of the alliance became more and more apparent. The whole construct had been based on necessity, not sympathy, often only covered by a thin veneer of politeness. Increasingly nervy diplomats had propped up the structure, helped by a very thin Austro-German elite of which Fürstenberg was a key member. The more strained everybody’s nerves became, the more Fürstenberg was therefore needed back from the front. Like most members of his peer group he was more or less an ‘ornamental soldier’, commuting between the front and his post as vice-president of the Austrian upper house. He had kept in touch with Austro-German affairs and, as Wilhelm’s closest friend, it seemed natural for the Kaiser to ask him to take up his old go-between work again. Fürstenberg accepted gladly. Yet to be a go-between in war would be a much more strenuous job than in peacetime. During the next four years the cheerful Fürstenberg aged rapidly.

To make his mission possible, Fürstenberg left the Austrian army at the end of 1915 and officially switched to the German army. This meant he could see the Kaiser twice a month.

How bad the communication channels between the Austrian and the German leadership had become by then can be seen by the bombardment of letters Fürstenberg now received. Though his private papers are uncatalogued one can wade through a mass of correspondence from his political friends in Austria who wanted him to act as a channel to Berlin. Fürstenberg was used to this and so far had enjoyed it. But he was not used to an avalanche. The Austrian minister Josef Maria Baernreither’s long memoranda, for example, were littered with points that Fürstenberg should make to the Kaiser. Fürstenberg’s annotations illustrate that he did try to discuss these issues with Wilhelm, but he knew that this was not enough. He was well aware of the fact that the Kaiser’s power had diminished and other decision makers had to be tackled. Fürstenberg therefore liaised mainly with members of the military and the German Foreign Ministry. These files indicate how often the Austrian government—via Fürstenberg—tried to convey its views to its German allies. Issues ranged from foreign policy subjects like a future kingdom of Poland to more pressing issues like food supplies.30

It was a delicate game for Fürstenberg. He had to work on two fronts—to negotiate with the German ally, and at the same time defend German policies in Vienna. He also had to please two very different courts. With the successor to the throne Franz Ferdinand gone, Fürstenberg had been without a key court contact in Vienna. He had never been close to Emperor Franz Joseph who allegedly found him too ‘flippant’. Considering the advanced age of the Austrian monarch, Fürstenberg knew that he had to bide his time. By 1916 Franz Joseph was dead and Fürstenberg’s influence at the Habsburg court improved. With his easy charm, he managed to develop a relationship with the new Emperor Karl. However, he never succeeded in becoming close to Karl’s wife Empress Zita and her powerful family, the Bourbon-Parmas. This would later turn out to represent a dangerous disadvantage for his missions.

Apart from cajoling emperors, Fürstenberg also had to keep his peer group in the upper house content. How difficult this could be can be illustrated by a session of the Austrian upper house in 1917. During a debate, the Archbishop of Lemberg, Józef Bilczewski, had attacked Germany. Fürstenberg as vice-president of the upper house rebuked him and warned ‘the Archbishop in sharp words, for which he was applauded by the whole house, even the Poles’. The Archbishop immediately played down his statements, saying that ‘he had not meant to offend’, and it was all a misunderstanding due to his inadequate German.31 (This was a rather feeble excuse since the Archbishop had once studied in Vienna. In the long term it worked, though, Józef Bilczewski was canonized in 2005 by a German Pope).

Despite such backpaddling Bilczewski was certainly not alone in his distrust of German policies. Many saw Fürstenberg as a German puppet.

This was not the perception of the German side. Though the German Foreign Ministry was grateful when Fürstenberg stood up for Germany in public, in private he was far more critical. The longer the war dragged on, the more Fürstenberg’s ‘begging missions’ irritated his German partners. One of Fürstenberg’s constant campaigns was to alleviate the food shortages in Austria-Hungary. The German embassy in Vienna reported as early as November 1916 that Fürstenberg had stressed that a continuation of Austrian support for the war depended on adequate nutrition for the Austrian population. He insisted that Hindenburg should be informed about this problem—having obviously given up on the Kaiser.32 It is therefore ironic that Fürstenberg’s opponent Josef Redlich accused him of being entirely in the German camp, while the German side suspected Fürstenberg of dramatizing the situation in Austria and being a tool of Austrian Foreign Minister Count Czernin. In some ways this was the natural dilemma for a go-between.

The perception that Fürstenberg was close to Czernin, the new Austrian Foreign Secretary, was, however, correct. Czernin needed Fürstenberg’s help. Both men had realized early on that the war was going badly for Austria-Hungary and that the only solution was a quick peace. Czernin was already arguing in 1916 that the war should be brought to an end. This was the only way in his opinion to stop the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire.

The main problem was that peace depended on Germany making territorial sacrifices. Czernin could not force Austria’s ally to make such a commitment. The hope was that Fürstenberg might help with the persuading. He was willing to get involved and also to initiate peace feelers. After 1918 these feelers would become an embarrassment and Fürstenberg must have destroyed some of his private correspondence relating to them. Since his papers are in a chaotic state, it is hard to tell whether letters were ‘displaced’ on purpose or accidentally. However, one of the clues for his involvement is hidden in an envelope entitled ‘Parliamentary life in 1916’.33

The contents of that envelope are intriguing: On 24 October 1916 a meeting took place in a Viennese flat owned by Max Egon Fürstenberg. He had invited pro-German aristocrats who were united by the wish to find a way out of the war. Present were Czernin, Baernreither, Clam-Martinic, and Nostitz. All of them would a month later be given key positions by the new Emperor Karl. At the meeting this ‘band of brothers’ entirely agreed that it was vital to convey to Germany, as Clam-Martinic put it, ‘that we just can’t go on anymore’. Once the message was understood, peace talks had to start. Fürstenberg himself considered the timing ideal. He argued that the Central Powers still had the largest amount of human resources and were not yet exhausted. If a peace deal was secured now they could recover quickly and ‘pursue their plans at a later opportunity’. He never elaborated on what this ‘later opportunity’ meant and it was obvious that this was sheer face saving.

The next question was who would agree to start peace negotiations with the Central Powers. Russia and France were according to Czernin out of the question. Britain seemed easier to approach. Czernin stressed that one should try to impress the message on London that there would be no winners or losers in this war, but that one had played a ‘partie remise’ (a game postponed). His chess metaphor seemed flippant considering the exorbitant death rate, but none of his friends minded the language. Only Clam-Martinic, who would soon run Emperor Karl’s cabinet, was pessimistic, believing that Germany would never agree to a key point on which the Entente Powers would insist, giving up territory. He conceded however that it was up to Austria’s diplomatic skills to persuade its ally. The prospect of an international peace conference might impress Germany. In the end all agreed that the King of Spain, Alfonso XIII,34 should be persuaded ‘to propose a peace conference in Madrid or The Hague as a result of which all nations relinquish territory and any idea of compensation’. The aim of the congress would be to recover the status quo ante bellum.

It was important that the King of Spain made this suggestion and not Austria-Hungary, otherwise she would lose face and her bargaining capacity would be lowered. To keep the whole plan secret, the Austrian ambassador to Spain should not be informed. This was not without irony, since the ambassador was Karl Emil Fürstenberg, Max Egon Fürstenberg’s younger brother. Though everyone trusted him, a leakage en route was always a possibility. Furthermore Karl Emil was not known for his acting qualities and by circumventing him he could react with genuine surprise, denying any knowledge of the offer. As Austrian ambassador he had to tread carefully in Madrid. While the Spanish King and the conservative party were considered to be pro-German, the Spanish Prime Minister Count Romanones was known to have pro-Entente sympathies.

Keeping Karl Emil Fürstenberg in the dark, however, posed another problem. If he was not used to deliver the details of the peace offers, the question arose how to get the message to the Spanish King. In the end it was decided to send a courier by submarine.35

Submarines had become the latest weapons of the war. Navigation with them was still a risky business and survival rates in battle were low. Still, the plan was successfully carried out. The U-boat surfaced in Cartagena and the letter it carried was for the King’s eyes only. However, the appearance of a submarine caused the wildest speculations. Bizarre rumours now circulated about Spain’s intention of giving up her neutrality. While Count Romanones was kept in the dark, the Spanish King enjoyed the rumours. His enthusiasm for secret games was one of the reasons he had been chosen by Fürstenberg and his friends. On a note during their meeting Baernreither had written:

Why Spain? First of all because of the able representative Karl Emil and because the King is laid back.36

King Alfonso was indeed ‘laid back’, a man who seemed to adapt to every political turn. He had studied in Austria and England and knew both countries well. As the son of a Habsburg princess he was a member of the Catholic network, but he also had good British links. His wife Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg had been born in Balmoral in 1887, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria. In a rare move for members of the Protestant network, she had switched to Catholicism to marry Alfonso at the age of 17. Despite, or because of, the birth of seven children, the marriage had deteriorated quickly. Their temperaments were hardly compatible. Looking at photographs of Victoria and Alfonso, even their visual differences are striking. While she had an intelligent face with inquisitive eyes, her husband looked like the cliché of a shifty gigolo (a cliché he tried to live up to by producing a multitude of illegitimate children). One of his excuses seemed to be that his wife, a carrier of haemophilia, was responsible for their sons’ illnesses.37 Yet despite their marital estrangement Alfonso made use of Victoria’s British contacts. Though he was a ruler only on the periphery, his Austrian/British links made him central to peace feelers, a centrality he very much enjoyed. Alfonso’s dream had always been to bring Spain into closer contact with the major European powers.38 From the start of the war he had therefore offered himself to all sides for peace talks. His motives were hardly altruistic. Parallel to supporting peace attempts, he kept trying to sell Spain’s neutrality to the highest bidder. He started with this double agenda in September 1914 by first offering the French ambassador his mediation between France and Germany.39 He also claimed that Germany had offered long-term compensation for Spain’s neutrality: Tangier, Portugal, and Gibraltar.40

In the end Spain did not manage to sell itself to anyone and remained neutral throughout the war. According to the rather Freudian interpretation of the Italian ambassador this was due to the influence of Alfonso’s mother. The Austrian Marie Christine apparently encouraged her son to stick to neutrality at all costs.

But even though Alfonso gambled with Spain’s neutral status, he also wanted to help his Austrian friends. To this day the Spanish royal archives are closed and his secret modus operandi remains obscure. However, as will be shown later, Alfonso was also involved in Lady Paget’s peace mission—which took place at the same time as the Fürstenberg one.

Despite the greatest efforts, the Austrian peace feelers via Spain suddenly stopped. Fürstenberg never forgot this failure and after the war tried to reconstruct why and by whom they had been terminated. In 1919 he had a conversation with the German General Consul in The Hague, Dr von Rosen. Rosen had been in Spain in 1916 and had conducted several conversations with the Spanish King. He confirmed that Alfonso XIII had wanted to help with the peace talks and via Rosen this message had been conveyed to Berlin. The Kaiser then ‘agreed with it enthusiastically’. So why had the feelers failed? Fürstenberg and Rosen came to the conclusion that the German Foreign Ministry had vetoed the plan in the end. It might have feared that its Austrian ally could use this channel to come to a separate peace agreement with Britain. To Fürstenberg the whole story proved one thing: that his friend Wilhelm had been seriously seeking peace. This was an important conclusion for him, because by then the ‘Hang the Kaiser movement’ was in full swing and Fürstenberg needed arguments to defend the ex-Kaiser. But even though Wilhelm II had supported the Spanish mission, Fürstenberg’s analysis had its flaws. The Kaiser’s mood swings were as unpredictable as his influence on political decisions. He probably did hope for a good outcome via Spain, yet he also had a tendency to change his mind—according to the military situation—several times a day. Ignorant about the true nature of the war he vacillated between advocating a quick peace one day and dictating the strictest peace terms the next.

The Spanish peace feelers of 1916 and 1917 also failed because Austria-Hungary came with heavy German baggage. The British were by then only interested in a peace deal with Austria-Hungary alone, hoping to divide the Central Powers.

The failure of the Spanish peace initiative was just one of many frustrations the constant go-between Fürstenberg suffered during the war. By the beginning of 1918 he had become desperate. To his old friend Clam-Martinic, who was now military governor in Montenegro, he wrote:

I could write you volumes about the situation here. Suffice it to say that I, a dedicated optimist, have started to wobble. One should suppress such feelings but I am sometimes getting really scared.

Viennese life depressed him: ‘I am so fed up with the political life. A constant tilting at windmills.’41

The abilities of German politicians did not give him much hope either. In February 1918 German diplomats reported that Fürstenberg had harangued them:

Fürstenberg says that even in German circles [in Vienna] resentment against Germany is growing. The reason for this is the feeling that Austria is fighting only for German conquests and economic compromises and will in the end be left empty handed … On this basis it is no longer possible to operate. Even Emperor Karl can, despite the best of wills, no longer stand up to public opinion. The alliance is therefore standing at the crossroads.42

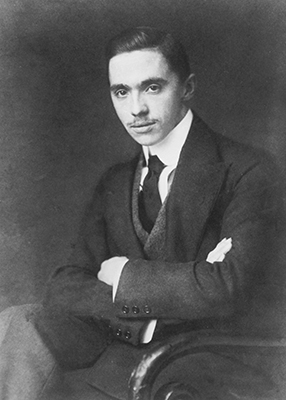

In fact the disintegration of the Austro-German alliance seemed unstoppable. It had been Fürstenberg’s raison d’être and he saw it faltering before his eyes. Ironically, the last nail in the coffin of the alliance was a rival go-between mission that went tragically wrong: the infamous Sixtus affair. The mission was set up unbeknown to Fürstenberg and would end up ruining everything he stood for. It is a well-documented affair, but it has never been seen in the wider context of go-between missions. However, it is very useful for understanding go-between work in general, because it illustrates the unpredictable dynamics of such work and the element of danger involved in them (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A mission that ended in scandal: Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, brother of the Austrian Empress Zita.

In the autumn of 1916 the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph had died and Emperor Karl and his wife Zita succeeded him. Zita had two brothers, Sixtus and Xavier of Bourbon-Parma. The Parmas were considered to be a highly ambitious family, deeply rooted in the Catholic network. In August 1914, two years before Karl succeeded to the Habsburg throne, he had had a long conversation with Zita’s brothers. The war had just begun, and Karl and Zita felt deeply ambivalent about their German ally. They agreed with Zita’s brothers that the war could ‘increase Prussian military power which would not only be a threat to French security but also to the independence of the Habsburg Empire’.43

When Karl succeeded to the throne, he (or his wife Zita) started to look for a back channel to the Parma brothers. They chose Princess Sarsina.44 She was a member of the Habsburg network and would now start to act on behalf of Empress Zita.

Sarsina was living in Italy when war broke out. When Italy sided with the Entente powers in 1915 she moved to Switzerland in protest against ‘Italian treason’. Living in the Swiss town of Fribourg also meant that she could stay in contact with both sides of her family—she had relatives in France, Italy, and in Austria-Hungary. Though she was born in France and married to an Italian, her loyalties were completely Austrian. She was a devout Catholic and particularly close to Maria Antonia of Parma, the mother of the new Austrian Empress Zita. Because of this background she seemed a natural for a go-between mission. But her work would not go unnoticed. Sir Hugh Whittal was working for MI6 in Switzerland. One of his best sources was the Swiss political department, which passed on intelligence to him. They were aware of the importance of Sarsina’s work. In a memorandum about the ‘Fribourg conversations’ Whittal wrote:

The central person of the whole affair is Princess Sarsina. … She is on friendly terms with the Dowager Duchess Maria Antonia of Parma (nee Princess of Braganza and Infanta of Portugal) who is the mother of the Empress Zita of Austria. Princess Sarsina is also on extremely friendly terms with the Empress Zita herself, with the Emperor Charles [Karl] and with many other important and influential persons at the Court of Vienna. … Princess Sarsina’s house has been during the last three years the scene of many meetings between various members of the various branches of the house of Bourbon and many Roman Catholic dignitaries and others who have been active pacifists.45

Most importantly the Swiss had seen (probably opened) a letter the Empress Zita had written to Princess Sarsina in early 1917: ‘the Empress Zita’s letter contained a reference to French rights in regard to Alsace-Lorraine. At the foot of this letter Emperor Charles [Karl] appended a word of greeting over his signature.’

From the intelligence report Zita emerges as the driving force. She wanted a quick peace: ‘the Empress Zita’s letter said that Austria did not desire to be ruined for the sake of saving Alsace-Lorraine for Germany.’

This was an entirely female network that only used men as a front. Behind the scenes women were dictating the agenda and the pace. That Zita and her mother were quite manipulative of the men they used even occurred to the intelligence agents: ‘the Duchess of Parma (Zita’s mother) in her great desire to bring about the conclusion of hostilities, may have misled the Emperor Charles regarding the strength of peace desires in France and Italy, and may have exaggerated the possibilities of success in bringing about a reconciliation between Vienna on the one hand and the Entente on the other.’

The Duchess of Bourbon-Parma saw negotiations with the Entente powers as a career chance for her sons, who were serving in the Belgian army. If Sixtus and Xavier could broker a peace between France and Austria-Hungary, their careers were secured. It was therefore the Duchess (with the help of Sarsina) who orchestrated a first ‘peace feeler’ meeting in Switzerland in January 1917. Everyone in this game naturally had their own complicated agendas. The Parma brothers’ first trip to Switzerland was cleared by the King of the Belgians and the French government. They realized that Sixtus and Xavier Parma were ideally placed to get in contact with Emperor Karl. The French probably also hoped that the Sixtus mission could sow discord among the Central Powers. However, they had no clear idea how ambitious the plan of the Parma family actually was. In fact Sixtus did not simply want to deliver a message—he wanted to write the message. He and his mother hoped for a big ‘scoop’, for the glory of the House of Parma. At the first meeting between the Parma brothers and their mother in Switzerland they discussed a list of demands that should be fulfilled by Austria-Hungary. In return for a peace deal with the Entente, Austria-Hungary should agree to: first making Germany return Alsace-Lorraine to France, secondly Belgium becoming sovereign again, thirdly Austria-Hungary relinquishing any interest in Constantinople, and finally giving Serbia its sovereignty back.

These demands were communicated to Emperor Karl’s private envoy, Count Thomas Erdödy. In his first reaction Emperor Karl agreed to all points apart from the last one, in a second reaction he backpedalled. Sixtus, however, kept insisting that all points had to be fulfilled. This put Emperor Karl in a dilemma. He wanted an honourable peace (which would mean including his German ally) but if that was not possible he needed to drop his ally to save his crown. Up to this point he had planned to run the Sixtus go-between mission himself, but he now realized that he needed the support of his Foreign Secretary Czernin. Czernin had to help him put pressure on their German ally. On his own Emperor Karl saw no chance of persuading the Germans to cede Alsace-Lorraine. Though Czernin was now brought in, he was not informed about all the details of the Sixtus mission. Karl simply told his Foreign Secretary that he might have found a way for peace negotiations with the French. Czernin was therefore under the wrong impression that the French had approached the imperial family, not the other way round. In fact during the whole mission Emperor Karl did not give Czernin vital details. Sixtus was his go-between and he wanted to keep it that way. To inform Czernin only ‘on a need-to-know basis’ naturally carried the risk of misinterpretations. As events would show, it would have been wiser to keep Czernin either entirely in or out.

Since Czernin worked under a misapprehension about France’s motives, he insisted on playing hardball. He wanted to achieve a peace that included Germany. Karl, pressured by his wife and the Parmas, was however now willing to drop his German ally if necessary. Since the outbreak of the Russian Revolution in March 1917, he had been in a state of panic. He kept asking his ministers the same question again and again ‘is it possible here too?’46 Czernin could not give him much assurance, and privately he confided to his friends that ‘the Russian Revolution is having an influence. Our dynastic roots might be stronger, but in the last three years a new world has emerged.’47

On 24 March 1917 Karl gave Sixtus a letter for the French in which he promised to do his utmost to impress on his German allies the ‘just’ French demands on Alsace-Lorraine.48 Furthermore, Belgium should be restored and be allowed to keep its African colonies. Serbia’s sovereignty should also be restored. Karl did not want to comment on Russia, while the revolution was still ongoing.

This was good material for Sixtus to use back in France. The French President was interested in Emperor Karl’s reply, yet he was also informed about Czernin’s much less lenient stance. It was obvious to him that the Emperor had promised concessions he might not be able to deliver. Czernin and Emperor Karl now seemed to compete with each other in sending out go-betweens to France. For Emperor Karl it was important that his brother-in-law Sixtus was achieving results first. Knowing that his Foreign Secretary did not approve of a separate peace, he had every reason to keep Sixtus, i.e. his cards, close to his chest. Meanwhile it had dawned on Czernin that he was not being fully informed. He had met Sixtus but did not approve of using him as a go-between. In rivalry with the Parma brothers he therefore set up another channel to France—Count Mensdorff. Mensdorff was a former diplomat and, unlike Sixtus, had the complete trust of Czernin. To get him into the game, Czernin seized on an interesting new offer. It came from a woman. Alexandra Barton, a member of the rich Peel family, was an English lady living in Switzerland. In March 1917 she approached an Austro-Hungarian diplomat informing him that the French were interested in a meeting with a high ranking Austrian emissary. At the centre of their talks should be peace negotiations. Count Czernin quickly picked up on this offer.

Alexandra Barton-Peel seemed to be a serious go-between, well connected to British and French political circles. This made her a highly useful commodity. So far the Entente powers had never agreed jointly on one go-between. On the contrary they had been jealous and highly suspicious of any contact the other party had made. Barton, however, seemed to be trusted by both—the French and the British. That made a constructive outcome more likely. Though Czernin was satisfied with her credentials, it is not actually clear who her French contacts were. On the British side they included the former Foreign Secretary Grey and the leader of the opposition Asquith. Both men obviously hoped to achieve a political scoop that might bring them back to power.

Barton seemed too good an opportunity to miss and Mensdorff was sent on his way. Though he was not a diplomat any more he would still have attracted suspicion. Swiss hotels in Berne and Geneva were crowded with people who reported on each other. Mensdorff therefore used an appropriate cover—he claimed to be working for the Red Cross. Once established he made contact with Alexandra Barton. He was impressed by her. She was obviously not an attention seeker but highly intelligent and without a doubt employed by high ranking members of the Entente powers. But her offer was a disappointment for Mensdorff and Czernin, who still hoped to find a peace proposal that included Germany. Lady Barton kept repeating that Britain and France sought peace with Austria-Hungary alone. She explained that no one would dare to start negotiations with Germany, because the jingoistic mood in England would not allow for it. Britain aimed for a complete victory over Germany and was confident that this could be achieved.49 Attitudes towards Austria-Hungary, however, were different. Nobody, Barton insisted, felt any hatred towards the Austrians; even Italy and Russia had no such feelings, while ‘the whole world was filled with hatred’ towards Germany. Mensdorff was taken aback by this and stressed that a separate peace with Austria-Hungary was impossible. In his memorandum to Czernin he summarized the impression Barton’s arguments had made on him:

Barton must have given him a hint in this direction. Yet, by now Czernin knew that it was hopeless to get the Germans to cede Alsace-Lorraine. Mensdorff was however not willing to give up so easily. At a further meeting with Alexandra Barton on 4 April he floated a scenario in which Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Russia would drop out of the war and the fighting would be continued by Britain, France, and Germany.51 It was blue-sky thinking, but must have encouraged the British not to give up on their Austrian contacts.

As we will see, Barton was not the only woman who carried out such clandestine negotiations. Like many other female go-betweens, she was discretion personified. It was only in her will that she gave an ironic hint of her work—a hint that so far seems to have gone unnoticed. In 1935 she bequeathed her house in Geneva—the Villa Barton and its extensive park—to the Swiss Confederation, so it could be turned into the Graduate Institute of International Studies.52 Barton obviously saw her go-between work as a useful tool for international relations. Today’s students are unaware that their benefactor had once tried to help such relations in her own way.

While Alexandra Barton stayed anonymous all her life, her rival go-between Sixtus of Parma was less lucky. During the whole Sixtus mission Emperor Karl had relied on the discretion of the people involved. This was a reasonable assumption, yet in times of war, ‘trust’ had become a rare commodity. Like so many other failed peace feelers the Sixtus one might have stayed secret, at least until the end of the war. Yet indiscretion—the greatest threat to all go-between missions—changed this overnight.

It was, of all people, the experienced diplomat Count Czernin who broke the rules. Though he knew all too well that mutual trust between parties involved in go-between missions was paramount, Czernin publicly announced that the French had made peace overtures to Austria-Hungary but that his government had stood by Germany. He must have known that the press would cover his statement at length. He also should have known that the French would retaliate. In fact Czernin had triggered a disaster. His speech was so completely out of character that nobody (including Czernin himself ) could later understand the motive behind it. One explanation was that he was still under the misapprehension that the initial overture had been made by the French. He was also ignorant about the letters Karl had sent via Sixtus to the French. Another reason for his speech could have been his desire to show himself as a man who had tried everything to achieve a peace deal, indicating that this peace would have been possible if Germany had not stood in the way of resolving the Alsace-Lorraine problem. This might have been a coded hint to the German ally. Still, it does not justify the recklessness of his remarks. A more simple explanation for them is that he was not acting rationally. His mental state was by then fragile. The war had taken its toll on everyone, but Czernin had known for almost two years that it was lost. By 1918 he was completely overworked and close to a nervous breakdown. His concentration had suffered and this might have made him say things off the cuff. Whatever the reasons, the speech would become his personal suicide note.

The French were outraged and decided to return the compliment, by publishing Emperor Karl’s incriminating letters ten days later. Czernin was naturally shocked. Emperor Karl then gave Czernin his ‘word of honour’ that no more letters existed. He also claimed he had never made any commitments in regard to Alsace-Lorraine. This was an obvious lie. It was now expected that Czernin would do the ‘honourable thing’ and shield the Emperor, taking sole responsibility and resign. He refused. As a consequence he was dismissed four days later.

Czernin’s career was over and Emperor Karl’s reputation tarnished. Fürstenberg, who had never liked Zita’s ‘awful family’, the Bourbon-Parmas, was outraged. He agreed with many members of Austrian society that the Parma intrigues had been responsible for this blunder. While everyone discussed whether Karl had actually lied to his minister or not, one thing seemed clear to many now—the Habsburg dynasty was severely damaged and might not survive the war.

The Sixtus mission was a debacle on several levels. Most importantly it ended the chances for any more Franco-Austrian peace feelers. It also made Austria-Hungary even more dependent on Germany while at the same time poisoning their relationship irrevocably.

Fürstenberg’s sentimental little poem about the two faithful brothers—Austria and Germany—seemed to mock him now:

The brothers did not separate but stood firm,

And fought without regret and treachery

The Nibelungen-fidelity became reality!

There was no trace of ‘Nibelungen-fidelity’ left. It was obvious to everyone that Karl had wanted to achieve a quick peace settlement to rescue his crumbling empire, and that he would have sacrificed his German ally to achieve this.

Apart from bringing about the beginning of the end of the German–Austrian alliance, the Sixtus mission also changed the public’s perception of their leaders. Censorship and propaganda had shielded people from the truth for four years. Now they saw an ‘international clique’ at work, which was acting outside the boundaries of government and the judicial system.

The American observer George D. Herron (1862–1925) saw the affair as a decisive turn. He wrote to the Secretary of the American Legation in Berne in May 1918: ‘[This scandal] seems to be the starting point for a new and searching examination of the psychology and the validity of the present modes of government.’

Herron was a theologian who had moved to Switzerland after the outbreak of war, explaining American policy to the Entente powers. Since 1917 his main role, had been to ‘sell’ President Woodrow Wilson’s ideas for a peace agreement. Apart from this Herron also wrote private reports to Wilson about the situation in Europe. The President liked receiving information from semi-official channels and for a while Herron was one of them.53 His take on the Sixtus mission was therefore important. He was well aware of how tired people had become of secret diplomacy and how much they yearned for more transparency. The Bolsheviks had by then published the secret treaties that tied the Entente together and the world had woken up to the fact that dubious negotiations had been concluded in the course of the war. The Tsar was out of action now, but the Austrian Emperor was very much in play. His handling of secret go-betweens and his lies showed how much the political classes had failed. Herron’s conclusions about the public’s outrage therefore just confirmed what Wilson had said only a few months previously. Number one of the President’s fourteen points had been to end secret diplomacy. The Sixtus scandal confirmed this. It was truly ironic that of all people Sixtus, the ambitious aristocrat, triggered a cry for democracy.

The fallout from the Sixtus mission for the Dual Alliance now became Fürstenberg’s problem. His go-between work continued, yet it had become pretty desperate. On 24 June 1918 he delivered Emperor Karl’s letter to the Kaiser, announcing that Austria would soon seek for peace. Though the war dragged on, everyone knew the situation was irrevocable. On one of his last missions Fürstenberg was sent to Wilhelm II to ‘beg’ for food supplies for the starving Viennese. The old link worked one last time. The Kaiser ruled in favour of his old friend’s country.

In October 1918 the German ambassador in Vienna reported that Fürstenberg had finally given up:

Prince Fürstenberg regards his efforts for a firm unity between the allied monarchies as having failed und has given up his political work.54

From this moment onwards Fürstenberg was no longer a go-between. However he stayed by the Kaiser’s side during the last days of his reign. In November 1918 he travelled to the German army headquarters and was shocked by the state of his old friend. Fürstenberg’s short diary entries of November 1918 show how claustrophobic the situation had become, with the Kaiser going on endless walks and taking too many sleeping pills. In this bunker atmosphere, nobody among the imperial entourage plucked up the courage to tell Wilhelm to abdicate. Fürstenberg was not capable of it either and noted: ‘I do not have the heart.’ To the end he was complicit in sheltering his friend from reality.

Fürstenberg and Wilhelm never got over the Sixtus ‘betrayal’. After the war, in 1921 Fürstenberg wrote a long letter to the depressed ex-Kaiser. To cheer him up he told him the story of another ex-emperor, Karl. Karl and his wife Zita seemed to live in much worse circumstances. They resided in the glorified Swiss ‘castle’ of Hartenstein, which apparently resembled more a ‘run down’ hotel than an imperial palace. Fürstenberg’s brother had just visited them and reported back that the ‘castle’ was overflowing with members of Zita’s pushy family, the Bourbon-Parmas:

They all intrigue and agitate for their own ends. My brother was relieved to get out alive … He thinks no fruitful action can be taken as long as the Parmas maintain their influence. But it seems to be impossible for Emperor Karl to get rid off his horrid in-laws.55

Wilhelm II and Fürstenberg had of course good reason to despise the Parma family for their involvement in one of the most damaging go-between missions of the war. Yet Fürstenberg’s fixation on the ‘Parmas’, i.e. Empress Zita and her mother, also shows that the aristocratic peer group often made wives responsible for the ‘bad’ decisions their husbands had taken during the war. While Empress Zita was condemned for dragging Emperor Karl into intrigues, in the case of Russia the Tsarina was posthumously made responsible for the downfall of the Romanovs while, as we will see, Queen Marie of Romania was accused of ‘manipulating’ her husband Ferdinand into war. All three women were portrayed in the manner of Lady Macbeth, employing rather doubtful methods for the survival of their house. Blaming the wives was a convenient way of exculpating the husbands. As in chess, sacrificing the Queen may be required to save the King. Consequently King Ferdinand’s, Emperor Karl’s, and Tsar Nicholas’s legacies stayed fairly intact. At least, within their peer group, they could still be portrayed as following the aristocratic code of honour. This tactic was rather misogynistic, but it also reveals another point. Queen consorts were perceived as serious players. In many cases this was a correct analysis. They could gain power, even if it was only behind the scenes.

But who were these women?

Go-betweens for two queens

In 1916 Queen Marie of Romania wrote to her British cousin King George V: ‘I never imagined that it would be the lot of our generation, we who were children together, to see this great war and in a way to have to remodel the face of Europe.’56

Though she was wildly exaggerating her role, the first part of her observation was of course correct.

Much has been written about the dilemma faced by the most prominent grandchildren of Queen Victoria in 1914: Wilhelm II, George V, and the Tsarina found themselves on opposite sides. But they were not the only royal grandchildren who had to cope with the break-up of their international family. Queen Victoria also had grandchildren living on the periphery of the war—in neutral countries. One of her granddaughters was the Queen consort of Romania, three others the Queen consorts of Spain, Greece, and Norway. All of these countries were neutral at the beginning of the war and therefore of great interest to the belligerent powers. Luring them out of their neutrality would have been a strategic as well as a propaganda success for each side.

It took Queen Victoria’s grandchildren some time to understand the implications of their new role. They had been brought up to believe in a strong family unit. Many had made friends with their cousins who were now in the enemy camp. Belonging to a royal cohort that was born in the late nineteenth century, they had never encountered a major European war. Instead they had been reared in an extremely sheltered environment, surrounded by growth and prosperity. Many of them had been born at their grandmother’s in Windsor, Osborne House, or Balmoral. Even their marriages had been influenced by Victoria’s wishes. Whether they married into German, Russian, Spanish, or Romanian royal houses, their reference point had always remained Britain. Long after the First World War and by then scattered across the Continent, they would still reminisce about summer holidays in Balmoral. In their memories Britain became a synonym for the innocence of their youth.

These grandchildren had always been conformists. In 1914, however, they were faced with a situation that demanded a very different attitude. Some realized this earlier than others. Marie of Romania was a romantic pragmatist and her above-mentioned letter to cousin George showed that by 1916 she had adapted to the new war games. While she still reminded George of the memories of an idyllic childhood, she was also pursuing a new agenda. The ‘remodelling plans’ she mentioned to cousin George turned out to be demands for territorial gains. Romania would be willing to join the Entente, if a long shopping list of territorial concessions was agreed on. In the end Marie would be successful in using her family network to help remodel Romania. But the road to this remodelling process was an unusual one.

Officially Marie had no power. She was ‘simply’ a consort, who was expected to produce children and look beautiful. In her memoirs she wrote:

My people always considered me pretty, and were proud of me, notre belle reine. In a way it was considered one of my royal duties to please their eyes, and yet it is the only duty for which I cannot be held responsible!57

Technically Marie’s husband was a very powerful monarch. In the First World War Romania was far from being a constitutional monarchy. In fact, King Ferdinand, together with his Prime Minister Bratianu, were the decision makers. Since Ferdinand was considered to be weak, people in the know turned to his wife Marie. She became the target of German and British go-betweens. That she was perceived by both sides as a potential ally was due to her ‘hybrid’ background.

Marie was born in England in 1875 and named after her mother the Russian Grand Duchess Marie, or Maria Alexandrovna. Her parents’ marriage had been a mistake. At least this was the opinion of Marie’s grandmother Queen Victoria. The Queen had not welcomed her second son Alfred marrying a Romanov. After the Franco-Prussian war Queen Victoria had given up the idea of playing politics by marrying off her children into foreign royal houses. Yet her son remained obstinate. He had already been forced to give up another marriage plan because of his mother’s interference and was now determined to push this one through. He also claimed to be in love with Marie Alexandrovna, though his mother doubted that he was capable of any serious feelings. Victoria was in general critical of her children, but she did have good reasons for not supporting the Romanov project. The Crimean war had deepened distrust in British society towards Russia and the Queen shared this feeling wholeheartedly. Political clashes with St Petersburg seemed likely in the future and Victoria rightly feared that a Russian daughter-in-law could become a long-term liability. Privately she thought the Romanov family itself was arrogant and full of ‘half oriental notions’.58

Victoria was proved right; the marriage was not very successful. But a son and four daughters were born before the couple became completely estranged. Whereas the son committed suicide, the daughters would play interesting parts during the First World War—three in the allied camp, one with the Central Powers. Like Chekhov’s Three Sisters, these four daughters dreamed of nothing more than to get out into the world. One of them actually made it to Moscow—Victoria Melita (‘Ducky’)—another found a Spanish princeling, and Marie became Queen of Romania. Alexandra (Sandra) was ‘only’ married to Prince Ernst Hohenlohe-Langenburg, yet it would always be the unglamorous Hohenlohe the sisters turned to when unpleasantness had to be sorted out.

Growing up with her siblings in Britain and Malta, Marie thought of herself as of mixed blood—Russian and English. Her mother Marie Alexandrovna was however suspicious of the English element. When Marie had the opportunity to marry ‘back’ into the royal family, her mother blocked it. She did not want her daughter to marry the second son of King Edward VII, George (later George V). Marie Alexandrovna favoured another offer. Over the years she would gain the reputation of marrying off her children young—a habit that Ernst Hohenlohe-Langenburg would call a ‘mania’.59 Following this mania, the 17-year-old Marie was quickly married to Ferdinand von Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, the Crown Prince of Romania. She did not enjoy the privilege at first. To move from prosperous Britain to poor Romania turned out to be a severe culture shock. Yet over the years Marie did develop into an enthusiastic Romanian. It was this newfound patriotism for Romania that explains her political work during the war, using all the family networks available to her.

In fact her involvement with go-betweens is one of the few better-documented cases of the First World War. The reason for this is that Marie was refreshingly indiscreet. Her three-volume memoirs which she published in the 1930s are—despite their flowery language and obvious self-aggrandizement—a useful source. So are her letters to friends in America, in which she gives colourful portrayals of her international relatives.

When war broke out in 1914 Marie was not yet Queen consort. Her uncle King Carol I of Romania had still three more months to live. King Carol was originally a Prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, who loved his ‘adopted country’ Romania. Yet adoption processes can be an emotionally draining experience and countries were not necessarily as grateful as lonely children. To adopt a country turned out to be a mixed blessing for the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen family.

As a member of the House of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen King Carol had always been pro-German. Though he was resentful that his relative Kaiser Wilhelm II had never shown much interest in or even visited Romania, when war broke out he favoured siding with Germany. King Carol mainly felt bound by treaty obligations. Despite many differences with Austria-Hungary, Romania had renewed a secret understanding with the Triple Alliance in 1913 and was therefore an ally of Germany, Italy, and Austria-Hungary.60

However, Romania’s ruling elite did not share the King’s enthusiasm for Germany and traditionally felt pro-French. For informed circles it was consequently no surprise that a compromise was reached and Romania declared herself neutral in 1914. It was a wise decision, but a decision the other nations did not accept. From this point onwards, the Entente as well as the Central Powers hoped to lure Romania out of its neutrality. The country became a battlefield of a different kind, with weapons that varied from threats and financial bribes to promises and flattery.

When King Carol died in October 1914, the new royal couple, Ferdinand and Marie, became the main target of diplomatic pressure from the Entente and the Central Powers to join the war.

Since the royal couple were part of an international royal network it seemed appropriate to send to them, apart from diplomats, people to whom they were related and whom they trusted. George V sent a special confidant to Romania, General Paget. The Central Powers even tried out three different go-betweens to put pressure on the royal couple: first Marie’s mother Marie Alexandrovna (by then dowager Duchess of Coburg), second, Marie’s brother-in-law Ernst Hohenlohe Langenburg, and third, King Ferdinand’s brother, Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen.61

The German line was simple: the new royal couple should be reminded of their German roots and of all the money Germany had poured into Romania. Emotional blackmail should be used if appropriate. Such blackmail was best carried out by a mother. Marie of Romania’s mother Marie Alexandrovna (dowager Duchess of Coburg) consequently demanded in her letters support for Germany. These were not simply the private letters of a controlling mother. They were commissioned by the German Foreign Minister von Jagow, who wrote happily in June 1915 that the correspondence was carried out satisfactorily.62 But letter writing was not enough. Jagow also wanted Marie Alexandrovna to travel to Romania to increase the pressure on her daughter. Marie Alexandrovna felt too old for such a strenuous trip. She suggested to Jagow that one of her sons-in-law, Ernst Hohenlohe-Langenburg, should go to Bucharest instead. The Foreign Minister hesitated at first. The trip of a man like Hohenlohe would be much more visible than that of an old mother. In June 1915 Jagow therefore telegraphed to his envoy in Bucharest:

Private. Strictly confidential. What influence has the brother-in-law of the Queen, Prince Hohenlohe on the royal couple? Would his visit be perhaps viewed favourably? Duchess of Coburg [Marie Alexandrovna], who does not want to go to Bucharest herself, seems to wish the visit to take place, but it could also be based on the wish to make her son-in-law play a political role.63

The reply of the German envoy was positive and Hohenlohe-Langenburg was dispatched to Bucharest.

While some members of the diplomatic service thought that one should avoid sending ‘amateurs’, others were more practical. One explanation for this was the mindset of civil servants in the German Foreign Ministry. They lived in a monarchy and were mainly aristocrats. Of the 550 diplomats who served in the German Foreign Ministry 70 per cent were members of the nobility. The decisive policy department in the Foreign Ministry, department IA, was until 1914 dominated by civil servants, 61 per cent of whom had an aristocratic background. Non-aristocratic civil servants were sidelined and ended up in less prestigious departments (economic, legal, or consular).64 It was therefore no surprise that the aristocratic civil servants believed in the benefits that could be achieved by dynastic contacts with other countries. Since diplomats did not want such a delicate task to be carried out by anyone outside their trusted circle it seemed sensible to employ private individuals, their fellow aristocrats. After all, these ‘amateurs’ understood the cultural context and often knew the decision makers personally.65

Once approached, members of the higher aristocracy usually agreed. Ever since the outbreak of war, they had wanted to prove their relevance and their ‘usefulness’. They had done this by getting involved in military and charitable projects. A semi-diplomatic role seemed even more prestigious.