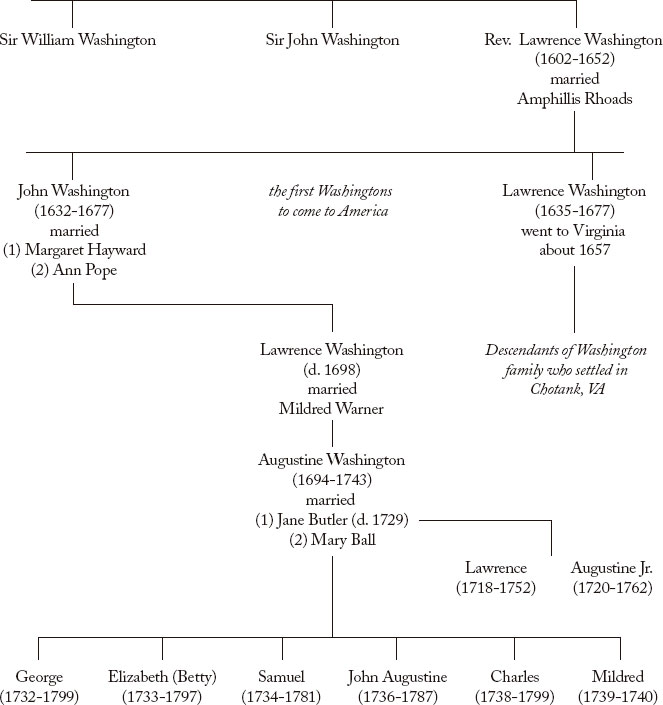

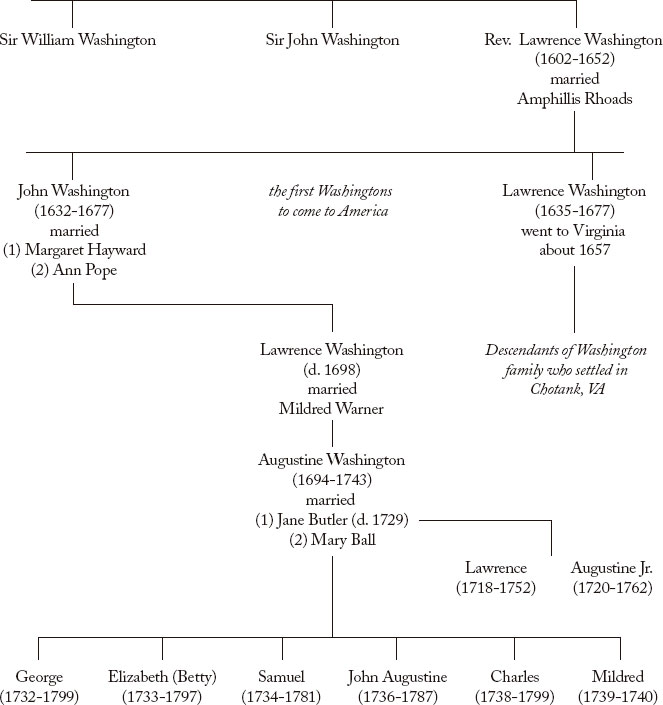

Colonel John Washington (1632-1677) and his brother Lawrence (1635-1677) were the first of the Washington family to come to the New World. John was George’s great-grandfather. They came as planters and businessmen in 1657. Their father back in England was the Reverend Lawrence Washington (1602-1652), an Anglican clergyman. One report says Lawrence may have been a heavy drinker.2 Whether that is true or not, he was loyal to the king, and that meant he was on the wrong side of Oliver Cromwell, the “Lord Protector,” in the aftermath of the English Civil War, during the days when England was kingless (1640-1660).

The seeds of Civil War were planted, in part, by the Anglican Church, which actively persecuted those who did not conform to its established worship. This persecution is what prompted the Pilgrims and the Puritans to come to American shores. King James died in 1625, and his son Charles I ascended to the throne, and he got into so many conflicts with Puritan nonconformists in his realm that it eventually led to England’s Civil War. Charles lost to a coalition of Puritans, Presbyterians, and Independents, led by independent Oliver Cromwell. Having been condemned by his conquerors as a tyrant, Charles was beheaded in 1649.

The twenty year period from 1640 to 1660 has been termed the Puritan inter-regnum. There was no King between Charles I and his son Charles II who assumed his hereditary throne in 1660. During this inter-regnum, those still loyal to the throne were out of favor. Thus, the Washington brothers left to attempt a new life in the New World. When George Washington looked back to this era, he referred to the Puritan victory over the King in the British Civil War as the “usurpation” of Oliver Cromwell.3 Along with their royal sympathies, the Washington brothers brought with them a Christian heritage in the Anglican tradition.

WASHINGTON’S CHRISTIAN ANCESTORS:

“BY THE MERITS OF JESUS CHRIST”

Both of the brothers had wills drawn up and recorded in Virginia that underscored their religious beliefs. Both wills were made in 1675, eighteen years after their arrival in the New World. They were probated only four days apart in 1677, suggesting that they had both died in the same year. Lawrence Washington said in his will,

I give and bequeath my soul unto the hands of Almighty God, hoping and trusting through the mercy of Jesus Christ, my one Saviour and Redeemer, to receive full pardon and forgiveness of all my sins. . . .4

John Washington, George Washington’s great-grandfather directed that a funeral sermon be preached and that a tablet with the Ten Commandments be ordered from England and given to the church. This would likely have been part of an improvement of the reredos in his local Anglican church.

The impact of John Washington on the history of Virginia, and thus on his great-grandson, was far-reaching. Washington parish was named for John, not, as many today would naturally assume, for his world famous descendant George, who would be born three generations later. John, like the future General Washington, was a military man.5 His fame in the parish was due to his military prowess as commander-in-chief of the Northern Neck—the approximately 1,400 square miles of land between the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers, granted to the Culpepper family by Charles II, which eventually came into the possession of the Fairfax family.6

JOHN WASHINGTON—GEORGE’S GRANDFATHER AND HIS FIRST ANCESTOR IN AMERICA

John was elected to the House of Burgesses in 1667, after ten years in the colony. Tradition says he was a surveyor, a seemingly trustworthy claim given the large tracts of land the early Washingtons accumulated in Virginia’s unsettled wilderness.7 Eight years later he was made a Colonel—the same year he made his will, 1675—and was sent with a force of a thousand men to assist the settlers in Maryland to defeat the Susquehannocks. John’s life anticipated George’s in many respects: a land surveyor, a successful soldier, a man with a keen sense of justice,8 an elected political leader, a man honored by lands being named in his memory, a Christian man.

John Washington earned a nickname among the Indians that was also applied to George a hundred years later. Great-grandfather John Washington had not only fought the Indians in Maryland, but he had also been the leader of the colonial army that drove the Indians far from the settlements along the lowland rivers in Virginia. The Indians named him, Conotocarious. When translated, this name can mean either “Town Taker” or “Devourer of Villages.” Joseph D. Sawyer writes, “From the site of the future Mount Vernon twenty-five hundred savages were driven over the hills into the Shenandoah Valley, in that early Indian war, by that first American Washington, who gained the name of “Conotocarius” (Devourer of Villages) through his prowess as an Indian fighter.”9

Years later, in 1753, in the unsettled wilderness, this name was also, according to author Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. “given to Washington by the Half-King, a prominent Seneca chief allied with the British against the French in the struggle for control of the Ohio Country.”10 In the Biographical Memoranda of 1786, written for his first and only approved biographer David Humphreys, Washington confirms this story. Speaking of himself, he says that he “was named by the Half-King (as he was called) and the tribes of Nations with whom he treated, Caunotaucarius or in English, the Town taker; which name being registered in their Manner and communicated to other Nations of Indians, has been remembered by them ever since in all their transactions with him during the late War.”11 George Washington, like his ancestor, John Washington, was a successful Indian fighter.

BACON’S “REBELLION” OR RESISTANCE TO TYRANNY?

Returning to the days of the Washington brothers, in the second half of the seventeenth century, the battles with the Indians took on a new significance in the two years between the time the Washington brothers made their wills in 1675 and died in 1677. In what has come to be called Bacon’s Rebellion, the Virginians produced one of the earliest civil wars in America as a byproduct of the ongoing conflict between the Native Americans and the settlers.

The nearly autonomous Sir William Berkeley, the longest serving governor of Virginia, ruled from 1641 to 1651 and again from 1660 to his death in 1677. With then capital Jamestown as his base, he governed his colony with a near absolute power. One of his critics was the Reverend William Drummond, who had recently arrived to serve the church. When the two met for the first time, Gov. Berkeley immediately issued a death sentence to his clerical critic: “I am more glad to see you than any man in Virginia. You will hang in half an hour.” The governor made good his fatal promise—only an hour and half late.

The settlers living on the frontiers were constantly under the threat of the Indians, while the settlers closer to Jamestown were far more secure. Petitions to Governor Berkeley, however, did not produce the protection they desired, apparently due to a conflict of interest. According to Washington historian Joseph D. Sawyer, Gov. Berkeley “knowingly allowed the Indians to sell him pelts [animal skins] with one hand while they tomahawked Virginians with the other.”12

Nathaniel Bacon was a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, who represented a parish that suffered from frequent Indian attacks. (Back then, Virginia was divided into parishes as opposed to counties, much like Louisiana is to this day.) When Bacon failed in securing permission from the governor to raise and lead a militia for the purpose of assaulting the Indians, he determined to take matters into his own hands. He raised a troop on his own to attack the warring Indians and was successful in his mission to drive away the marauding warriors.

Gov. Berkeley, however, declared that Bacon was a rebel. Bacon’s grateful constituents, nevertheless, reelected him to office in the House of Burgesses. The Governor decided not to prevent him from taking his seat. But when Bacon repeated his attacks upon the Indians, contrary to the Governor’s will, Gov. Berkeley raised his own army to quell the rebellious Indian fighter. However, Bacon’s smaller force, with its greater military experience, successfully attacked Jamestown. In 1676, Bacon’s force drove out Gov. Berkeley and his army and burned the city and its church to the ground to prevent the Governor from returning to Jamestown and making it his stronghold. The fighting finally ceased when King Charles II, the restored British monarch, finally recalled the beleaguered and much-hated governor.

When King Charles II summarized the governor’s reign of terror, he declared that Berkley had hanged more Englishmen (in Virginia) than he himself had executed in avenging the beheading of his father (in England).13

What makes this tumultuous history important is that it was part of the Washington family history. For, as Sawyer points out, “John Washington. . . joined Nathaniel Bacon—often called ‘the young Cromwell’—in hurling defiance at loot-saturated Governor Berkeley of hated memory.”14 Three generations later, Washington himself would be in a similar position to his forbearer John. He too would feel compelled to take up the just cause of colonists against the tyranny of royal officials in the New World. It is ironic that Washington referred to Oliver Cromwell’s leadership in the English Civil War by the use of the term “usurpation.”

LAWRENCE WASHINGTON: GEORGE WASHINGTON’S GRANDFATHER

Colonel John Washington died in 1677 in his early forties. He left behind his sixteen-year-old son, Lawrence Washington (1660-1698). Lawrence was George’s grandfather.15 Death came all too early, all too frequently in the colonial era. John buried not only his first wife, but also two of their children. Lawrence was born to John and his second wife. Lawrence was given the name of his Uncle Lawrence, who had come to America at the same time as John. Both had John’s clergyman father, Lawrence Washington (the allegedly drunken vicar), as their namesake.

While not much is known about his life, Lawrence (George’s grandfather) was also a military man and was known as Captain Washington. When he died in 1698, at his home at Bridges Creek in Westmoreland County Virginia, he was only thirty-eight. He left behind his wife, Mildred Warner Washington, and three children, the second being four-year-old Augustine Washington, future father of George. Lawrence’s will divided his estate between his wife and children. He directed that his children were to continue under the care and support of their mother until they were married or came of age.

GEORGE’S FATHER, AUGUSTINE

In the spring of 1700, two years after Lawrence died, Mildred (George’s grandmother) married again. She wed a Virginian, George Gayle, who was originally from England. Soon after the marriage, George Gayle moved young Augustine Washington and the family to England to live. But in January 1701, Mildred died in childbirth, when Augustine was only seven. Gayle proved to be a caring stepfather, and he enrolled his young stepson at Appleby School in Westmoreland, England. Again, Augustine Washington (1694-1743) was the father of George, and as we will see in a subsequent chapter, Augustine’s studies at Appleby School would directly impact George by bringing “The Rules of Civility” into his childhood education. One of those Rules was the 108th: “Honour and obey your natural parents altho’ they be poor,” which George copied in his school papers as a young teenager.

Meanwhile, in 1704, John Washington of Chotank, Virginia, (a cousin of Lawrence and the executor of his estate, descending from Lawrence Washington, the younger of the two Washington brothers who first arrived in Virginia) was awarded custody of the three children of their now deceased parents, Lawrence and Mildred Washington. So, while George Washington’s father spent a few early years in England, Augustine was soon to return to his native Virginia.

Augustine returned to Virginia at the age of ten, and for the next decade lived in Chotank, not far from his deceased father’s farm at Bridges Creek. This plantation became Augustine’s in 1715, when he came of age.

Whether Augustine was named in honor of the early Church father (St. Augustine), who was so much appreciated by Protestants (and Catholics alike), is unknown, as there is no record as to the source of the name of this first Augustine Washington. Others of the Washington family, however, would bear his name. Generally, the name of Augustine is derived from the great fourth century Christian theologian and Bishop of Hippo in North Africa.

Apparently, young Augustine thought highly of his education at Appleby and likewise appreciated his stepfather, George Gayle, back in England, for Augustine sent his first two sons (George’s older half-brothers Lawrence and Augustine, Jr.) to be educated at Appleby. Furthermore, Augustine, Sr., named his third son George—the first of several Washingtons to be named George, presumably after George Gayle, his stepfather. Thus, George Washington seems to have been named after his father’s stepfather, George Gayle.16

Shortly after George’s father, Augustine, turned twenty-one in 1715, he inherited his late father’s Bridges Creek plantation. Grizzard describes what he received:

Augustine’s inheritance included more than 1,000 acres of land (much of it under cultivation by that time); a sizeable amount of tobacco; a half dozen slaves; farm implements and other tools; and livestock consisting of four horses, six sheep, twenty-two cattle, and forty-four hogs. In addition he received a large assortment of house hold goods and eleven books.17

About that time, Augustine married his first wife, a Virginia girl from Westmoreland County named Jane Butler (1699-1729), whose holdings increased his lands to over 1700 acres.

Before Jane died at thirty years of age, she and Augustine had four children—George not being among them. One died in infancy, another in early childhood, and two boys—Lawrence (1718-1752) and Augustine, Jr. or “Austin” (1720-1762)—reached adulthood. These two brothers were George’s half-brothers. Again, they would attend Augustine’s Appleby School in England.

In 1731, Augustine remarried. His second wife was Mary Ball (1708-1789), mother of George, Augustine, Sr., and Mary, who was sixteen years younger than her husband, had six children. They were George (1732-1799), Samuel (1734-81), John or “Jack” (1736-1787), Charles (1738-99), Elizabeth or “Betty” (1733-97), and Mildred (1739-1740).

Augustine was active in the Washington family business of land acquisition and development. He farmed, operated an iron works, and was active in the life of the church. He built a home on Popes Creek at a picturesque point where it entered into the Potomac (an Indian word meaning “river of swans”).

What did George’s father look like? He was tall and athletic, like his world-famous son. Robert Lewis, George Washington’s nephew (son of Betty, his only sister) passed along a description of George’s father made by: “Mr. Withers of Stafford, a very aged gentleman.” Withers “remembered Augustine as being six feet tall, of noble appearance, and most manly proportions, with the extraordinary development of muscular power for which his son [George] was afterward so remarkable.” According to Withers’ recollections, when Augustine was the agent for the Principio Iron Works, he had been known to “raise up and place in a wagon a mass of iron that two ordinary men could barely raise from the ground.” Despite such physical prowess, Withers also remembered Augustine as a gentle man, “remarkable for the mildness, courtesy, and amiability of his manners.”18

When the family home was lost in a fire, the couple, with their firstborn child George, moved to a farm near Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock River. This residence became the childhood home of George. Known as Ferry Farm, one can still visit the grounds and a replica of the house to this day.

ACTIVE IN CHURCH DUTIES

Shortly after their move, Augustine Washington assumed the office of vestryman on November 18, 1735, when George, his first-born son by his second marriage, was only three years old. A vestryman was a lay-leader in the church. The oath required for Augustine Washington to become a vestryman was: “I, A B, do declare that I will be conformable to the Doctrine and Discipline of the Church of England, as by law established.” What did those Doctrines of the Church of England include? The classic teachings of Christianity: a belief in the Trinity, the deity of Christ, His atoning work on the cross, His resurrection from the dead, His ascension into heaven, His second coming, and the inspiration and authority of the Bible.19

Nearly thirty years after his father, George took the same oath on August 19, 1765, having been elected to the vestry of Truro Parish on October 25, 1762. The Vestry book of Pohick Church has the following record: “George Washington Esqr. took the oaths according to Law repeated and subscribed the Test and subscribed to the Doctrine and Discipline of the Church of England in order to qualify him to act as a Vestryman of Truro Parish.”20

THE DEATH OF GEORGE WASHINGTON’S FATHER

Augustine died in April 1743, after he caught a cold by riding his horse in a severe storm. George was only eleven years old. Writer Benson Lossing describes the details:

One day early in April, 1743, Mr. Washington rode several hours in a cold rain storm. He became drenched and chilled. Before midnight he was tortured with terrible pains, for his exposure had brought on a fierce attack of hereditary gout. The next day he was burned with fever. His malady ran its course rapidly, and on the 12th he died at the age of forty-nine years. His body was laid in the family vault at Bridges Creek.21

Mary Washington was only thirty-seven. Lossing adds, “She submitted to the Divine Will with the strength of a philosopher and the trustfulness of a Christian.”22

A family tradition recorded by George’s adopted stepgrandson gives a glimpse of Augustine’s dying scene:

The father of the Chief made a declaration on his deathbed that does honor to his memory as a Christian and a man. He said, “I thank God that all my life I never struck a man in anger, for if I had I am sure that, from my remarkable muscular powers, I should have killed my antagonist, and then his blood at this awful moment would have lain heavily on my soul.”23

Like father, like son. Augustine’s son, who would become the “Chief,” would also have a reputation for extraordinary strength and would also die of an infection from a cold caught after riding in a storm—and have a deathbed narrative to leave for posterity.

Augustine’s business acumen enabled him to divide 10,000 acres of land and nearly fifty slaves in his will. His estate provided for his wife Mary, and the bulk of the rest was given to his three oldest sons—Lawrence, Augustine, and George. Augustine, Jr., received the Pope Creek farm, where he had continued to live after the family had moved. Lawrence received the plantation that he would rename Mount Vernon, in honor of a commanding officer he had served with in military duty. Of course, this would eventually become the property of George, when Lawrence died. (Lawrence’s only heir, a daughter, died in childhood.) From his father’s estate, George received the farm in Fredericksburg that was known as the Ferry Farm because a ferry crossed the river by their land. This, however, was kept under the guardianship of his mother, until he came of full age.

Furthermore, George’s two older half-brothers—Lawrence and Augustine, Jr.—would serve as surrogate fathers for young George, when Augustine died. Both brothers were in their mid-twenties at that time. Because his father died so early, with insufficient funds available, plans to send George to Appleby School in England had to be scrapped. It is intriguing to wonder if George would have become the leader of the American Revolution had he attended Appleby.

CONCLUSION

Thus, our illustrious founding father came of age in a Virginia steeped in a long history of English and Anglican values, where the Indians were no longer a threat, and an agricultural culture was built on vast lands, tobacco, and slave labor. The unhurried life of the gentleman farmer had become a reality. The rural routine and pastoral pleasures of the plantation gentry were periodically interspersed by a journey to lead, serve, and socialize with others of the ruling class in the House of Burgesses, meeting in Williamsburg. Ideally, a Virginia nobleman’s son should have been educated in England. But Augustine’s untimely death prevented his young son from having the benefit of this experience. However, young Washington still needed to be properly educated, and he was. We will next consider his early childhood and education, which would prepare him for service to the community and impact him throughout his unique and renowned life.