We shall continue to let Washington speak for himself regarding his religion, but we will now address his generally non-disclosing personality in the context of the moral commitments of his character that we have just explored. As we seek to understand Washington, who in many ways was truly a private man, we will next seek to engage the personality of the man himself. His high regard for personal privacy joined with his deep reluctance to speak of himself, have been misinterpreted by many to imply he did not have a Christian faith. We are persuaded by Washington’s own self-revealing letters that to interpret his personality in this way, we will never encounter the real Washington, the human being beneath the aura of glory and the warm-hearted man hidden within a persona of quarried stone.

DESCRIPTIONS OF WASHINGTON BY HIS CONTEMPORARIES

When we consider the momentous character of Washington and the praise he was given by his contemporaries, we can see why it has been difficult to understand him as a humble human being. How can we distinguish between the way his followers saw him and the way he saw himself?

In his book, Washington on Washington, Paul M. Zall writes:

The difference may be inferred from passages that talk about himself in his own writings, both public and private. The public statements fit the Olympian image of Washington in the national memory. The private statements in his journals and letters sometimes reveal a different person—one who will overflow with romantic feelings or wallow in sentimentality or explode with spontaneous wit, even in the privacy of a diary.

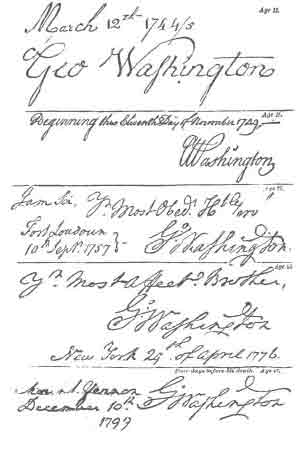

A quintessentially private person, Washington had a natural reluctance to express his feelings at all, a reluctance that was rein forced when his words were published to public scorn. He would be known by deeds, not words, but his written words remain to mirror him, often obliquely.

The person and character of Washington did, of course, easily lend themselves to national deification. He was of the stuff of heroes. He even looked the way a hero should look—tall and handsome powerfully built and graceful. Jefferson said of him: “His person was fine, his stature exactly what one would wish, his deportment easy, erect and noble; the best horseman of his age, and the most graceful figure that could be seen on horseback.”

His sheer presence impressed everyone. Abigail Adams thought he had more grace and dignity than King George III.2

Even one of George Washington’s slaves weighed in on the impact of his personality, as Washington biographer Saul Padover writes:

And his Negro servant, recalling the twenty-seven-year-old Washington’s marriage to Martha Custis, exclaimed that there was nobody, in that glitterin’ wedding assemblage, like the young Colonel: “So tall, so straight! And . . . with such an air! Ah, sir, he was like no one else! Many of the grandest gentlemen in their gold lace were at the wedding, but none looked like the man himself.”3

To some degree, Washington made it difficult for people to know his personality, much less his own private beliefs. Benson Lossing writes, “It was a peculiar trait of his character to avoid everything, either in speech or writing, that had a personal relation to himself.”4

More than thirty years after his death, Bishop William White wrote on Nov. 28, 1832, “I knew no man who so carefully guarded against the discoursing of himself, or of his acts, or of any thing that pertained to him; and it has occasionally occurred to me when in his company that, if a stranger to his person were present he would never have known from anything said by the President that he was conscious of having distinguished himself in the eye of the world. His ordinary behavior, although exceptionally courteous, was not such as to encourage obtrusion on what he had on his mind.”5

In confirmation of this observation, Washington himself wrote: “Having been thus unwarily, and I may be permitted to add, almost unavoidably betrayed into a kind of necessity to speak of myself, and not wishing to resume that subject, I choose to close it forever by observing, that as, on the one hand, I consider it an indubitable mark of mean-spiritedness and pitiful vanity to court applause from the pen or tongue of man; so on the other, I believe it to be a proof of false modesty or an unworthy affectation of humility to appear altogether insensible to the commendations of the virtuous and enlightened part of our species.”6

Thus, the historian has his work cut out for him to try and find the real George Washington. The man himself did not make it easy for us, nor was that his intention.

SHYNESS INTERPRETED AS ALOOFNESS

George Washington certainly carried himself with a reserved dignity. But his shyness was sometimes interpreted as aloofness. In a letter to French Ambassador, Eléonor Francois Élie, Washington apologized for the aloofness of the American people. On March 26, 1788, Washington wrote

I have even hoped, from the short time of your residence here, and the partial acquaintance you may have had with the characters of the persons, that a natural distance in behavior and reserve in address, may have [not] appeared as intentional coldness and neglect. I am sensible that the apology itself, though it should be well founded, would be but an indifferent one, yet it will be better than none: while it served to prove that it is our misfortune not to have the same chearfulness in appearance and facility in deportment, which some nations possess. And this I believe, in a certain degree, to be the real fact; and that such a reception is sometimes given by individuals as may affect a foreigner with very disagreeable Sensations, when not the least shadow of an affront is intended.7

George Washington was actually commenting in good measure on himself as well. Washington’s apparent coldness left people with various reactions. A Mennonite minister from the Netherlands named Francis Adrian Van der Kemp found Mount Vernon, as did many visitors, to be a place “where simplicity, order, unadorned grandeur, and dignity, had taken up their abode,” although he detected in his host “somewhat of a repulsive coldness under a courteous demeanour.”8 One visitor described Washington as “morose.”9 U. S. Senator William Maclay from Pennsylvania described the President as “pale, nay almost cadaverous.”10

Washington’s personal sense of decorum and the personal space of office and honor seems to have added to this impression of a cool, relational aloofness. Benson Lossing relates a telling anecdote:

It is related of the Honorable Gouverneur Morris who was remarkable for his freedom of deportment toward his friends, that on one occasion he offered a wager that he could treat General Washington with the same familiarity as he did others. This challenge was accepted, and the performance tried. Mr. Morris slapped Washington familiarly on the shoulder, and said, “How are you, this morning, general?” Washington made no reply, but turned his eyes upon Mr. Morris with a glance that fairly withered him. He afterward acknowledged, that nothing could induce him to attempt the same thing again.11

A spiritual variation on the theme of Washington’s coolness is seen in the writings of Thomas Coke and Francis Asbury. These two founding Methodist clergymen in America paid a visit to Washington seeking support for their anti-slavery petition.12 Asbury’s record of the May 26, 1785, visit simply said, “We waited on General Washington, who received us very politely, and gave us his opinion against slavery.”13 But Coke’s journal included a more substantial description of their visit,

The general’s seat is very elegant, built upon the great river Potomawk;...He received us very politely, and was very open to access. He is quite the plain country gentleman and he is a friend to mankind. After dinner we desired a private interview, and opened to him the grand business on which we came, presenting to him our petition for the emancipation of the negroes, and intreating his signature, if the eminence of his station did not render it inexpedient for him to sign any petition. He informed us that he was of our sentiments, and had signified his thought on the subject to most of the great men of the State: that he did not see it proper to sign the petition, but if the Assembly took it into consideration, would signify his sentiments to the Assembly by a letter. He asked us to spend the evening and lodge at his house, but our engagement at Annapolis the following day, would not admit of it. I was loth to leave him, for I greatly love and esteem him and if there was no pride in it, would say that we are kindred Spirits, formed in the same mould. O that God would give him the witness of his Spirit!”14

Washington’s impact on Coke was positive, yet even with Coke’s sense of a personal “kindred spirit” with Washington, he left praying for Washington’s reception of “the witness of the Spirit.” However, by the time of Washington’s presidency and later at his death, these founding bishops of the American branch of the Methodist Church viewed Washington as a Christian. Asbury’s words at Washington’s death were, “Matchless man! At all times he acknowledged the providence of God, and never was he ashamed of his Redeemer. We believe he died not fearing death.”15

In his leadership style, George Washington normally maintained a distance that forbade a familiar intimacy or a transparent disclosing of his thoughts or feelings. Yet his reserve in interpersonal relationships did not translate into an arrogant or haughty spirit. Instead, he was also known for his humility

HUMILITY

Washington’s humility is reflected in Zall’s description of how on one occasion as he was on his way to Mt. Vernon, he was caught in a heavy rainfall. The drenching rain forced him to leave his horse and take a “common stage.” Zall writes, “When the coach stopped at a tavern the innkeeper invited the General to the private parlor, but Washington protested: ‘No, no. It is customary for the people who travel in this stage always to eat together. I will not desert my companions.’”16 What is captured in this anecdote is evident in Washington’s words as well.

When George Washington was offered the position of commander in chief of the Army of America, he felt unworthy of the task, and he said so. Here is a portion of his speech to the Continental Congress on June 16, 1775:

Mr. President,

Though I am truly sensible of the high honor done me in this appointment, yet I feel great distress from a consciousness that my abilities and military experience may not be equal to the extensive and important trust. However, as the Congress desire it, I will enter upon the momentous duty and exert every power I possess in the service and for support of the glorious cause. I beg they will accept my most cordial thanks for this distinguished testimony of their approbation. But lest some unlucky event should happen unfavourable to my reputation, I beg it may be remembered by every gentleman in the room, that I this day declare with the utmost sincerity I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with.

As to pay, Sir, I beg leave to assure the Congress, that as no pecuniary consideration could have tempted me to accept this arduous employment at the expense of my domestic ease and happiness, I do not wish to make any profit from it. I will keep an exact account of my expenses. Those I doubt not they will discharge, and that is all I desire.17

He was willing to be reimbursed for his expenses, but he was not willing to receive pay.18 He expressed his feeling that he was not worthy of the task, but if Congress felt he could lead effectively, he felt honored. He wrote a letter to Martha around that time expressing similar thoughts and also mentioning that he would trust in God to see him through.19

About a year and a half later, he explained to Congress: “I have no lust after power but wish with as much fervency as any Man upon this wide extended Continent, for an opportunity of turning the Sword into a plow share.”20 Communicating this same humility, he wrote to his brother Augustine:

I am now to bid adieu to you, and to every kind of domestic ease, for a while. I am embarked on a wide ocean, boundless in its prospect, and in which, perhaps, no safe harbor is to be found. I have been called upon by the unanimous voice of the Colonies to take the command of the continental army; an honor I have neither sought after, nor desired, as I am thoroughly convinced that it requires greater abilities and much more experience, than I am master of, to conduct a business so extensive in its nature and arduous in its execution. But the partiality of the Congress, joined to a political motive, really left me without a choice; and I am now commissioned a General and Commander-in-Chief of all the forces now raised, or to be raised, for the defense of the United Colonies. That I may discharge the trust to the satisfaction of my employers, is my first wish; that I shall aim to do it, there remains as little doubt of. How far I shall succeed, is another point; but this I am sure of, that, in the worst event, I shall have the consolation of knowing, if I act to the best of my judgment, that the blame ought to lodge upon the appointers, not the appointed, as it was by no means a thing of my seeking, or proceeding from any hint of my friends. I shall hope that my friends will visit and endeavor to keep up the spirits of my wife, as much as they can, as my departure will, I know, be a cutting stroke upon her;21

By coupling humility with a sense of official distance, Washington carried himself with what could be called a reserved dignity.

RESERVED DIGNITY

George Washington had a commanding presence that left many with a sense of awe. Zall describes the impact he had on those who knew him or observed him: “Thomas Jefferson said that Washington hated the ceremony of the office but played up to the public’s expectations of it. John Adams called Washington ‘the best actor of presidency we have ever had.’22 In other words, being president called on one to act in a dignified manner—to Adams, George Washington played the part better than any-one. Abigail Adams marveled at the way he could balance the opposite and discordant ‘dignity that forbids familiarity’ with the ‘easy affinity which creates Love and Reverence.’ Even British observers wondered at this Socratic art of ‘concealing his own sentiments and of discovering those of other men.’”23

His impact was felt even on those who did not like him or what he stood for. Zall explains: “Even cynics marveled at his bearing. His natural dignity defied description. Sir James Bland Burges saw him as ‘cold, reserved, and even phlegmatic without the least appearance of haughtiness or ill nature,’ with an odd compound of pride and ‘constitutional diffidence.’”24

Washington was even concerned for a balance of humility and honor in his appearance. This is seen as he began to prepare a new American Army to defend the nation in the event of a French invasion in the aftermath of the French Revolution. When the then retired president was asked about his new uniform, he noted, in a letter to James McHenry on January 27, 1799:

On reconsidering the uniform for the Commander-in-Chief as it respects myself personally, I was against all embroidery.”25 [Similarly, Washington wrote to his nephew and spoke about the dangers of vanity as seen in showing off expensive clothing:] “Do not conceive that fine clothes make fine men any more than fine feathers make fine birds. A plain genteel dress is more admired, and obtains more credit than lace and embroidery, in the Eyes of the judicious and sensible.26

A spirit of humility had marked his life from early on. The agent who oversaw his business dealings in London in 1758 once incorrectly called him “ye Honorable.” Washington promptly corrected and clarified the potentially flattering bestowal of a prestigious title: “You are pleased to dub me with a title I have no pretensions to—that is, ye Honorable.”27 Washington would not rest in mere words. If he was to be “ye honorable” his deeds, not words alone, would have to prove it so.

DEEDS, NOT WORDS

One of the best ways to interpret George Washington’s life is to understand his philosophy of “deeds, not words”. Nelly Custis, Washington’s adopted granddaughter, said, “His mottoes were, ‘Deeds, Not Words’; and ‘For God and My Country.’”28 For example, he wrote Major General John Sullivan on December 15, 1779:

A slender acquaintance with the world must convince every man, that actions, not words, are the true criterion of the attachment of his friends, and that the most liberal professions of good will are very far from being the surest marks of it.29

Washington wrote to Patrick Henry on January 15, 1799: “The views of men can only be known, or guessed at, by their words or actions.”30 Accordingly, he utilized the power of symbolic actions. At the beginning of the Battle of Yorktown, he dug with his own hands into the soil of Yorktown to signify the start of the siege, and once both French and American cannons were in place, he fired the first round. He underscored his written orders by powerful and meaningful visible actions to inspire his men.

Thus, George Washington preferred to be known as a man of “deeds not words.” Writing to James Anderson on December 21, 1797, he explained,

If a person only sees, or directs from day to day what is to be done, business can never go on methodically or well, for in case of sickness, or the absence of the Director, delays must follow. System to all things is the soul of business. To deliberate maturely, and execute promptly is the way to conduct it to advantage. With me, it has always been a maxim, rather to let my designs appear from my works than by my expressions.31

Even the words of the motto found on the Washington family’s historic British Coat of Arms, “Exitus Acta Probat”, when translated from Latin means “The end proves the deed.”32 The Washington heritage emphasized actions rather than words.

We must interpret George Washington on his own terms. To insist that only his written words will give him meaning is to deny the very motivation of his own conduct—actions spoke louder than words. It is important for the debate we pursue in this book to underscore that Washington never declared himself to be a Deist, and he did declare himself to be a Christian. But, as critical as this is, Washington’s actions were intended to speak louder than his words. Accordingly, throughout this book, we will demonstrate his Christian worship, his Christian prayers, his other Christian actions, alongside the words of his writings that also reflect the presence of numerous Christian ideas.

EXPERIENCES THAT TAUGHT WASHINGTON TO GUARD HIS WORDS

It may be that part of Washington’s reticence to express his own feelings is that he was “gun shy,” so to speak. Apparently, he had recklessly expressed his feelings as a young man, and these expressions came back to haunt him. Two incidents in the 1750s, in particular, come to mind. The first was a hasty signing of a poorly translated agreement of surrender with the French at Fort Necessity, by which Washington unwittingly and incorrectly admitted to having assassinated a French ambassador.33

The second incident occurred in this same context. Compounding this misstep (or intentional French deception) during his surrender, Washington sent his brother a letter celebrating the delights of battle: “I heard Bullets whistle and believe me there was something charming in the sound.”34 The French intercepted the letter and subsequently published it throughout the Western world. The remark, when eventually read by British King George II (father of George III), caused him to remark, “He would not say so, if he had been used to hear many.”35 Twenty years later, in 1775, when someone asked if he had actually made that foolish statement, Washington answered, “If I said so, it was when I was young.”36

Another reason for silence on personal matters was that letters in that day were unreliable and liable to miscarriage, interception, misuse and sometimes, such as in times of war, were even subject to being replaced with spurious letters. Washington was the target of spurious letters and on occasion had to refute them.37 Along with the obvious reason of preserving their cherished privacy after a very public life, this may have been part of the reason Martha burned their letters after George’s death. At any rate, painful personal experiences seem to have helped seal Washington’s lips when he was tempted to speak of himself.

WISE ABOUT HISTORY; UNCONCERNED ABOUT LEGACY

Again and again, Washington showed himself to be more of a man of action than words. Yet the lessons of the past mattered to him. He wrote to Major General John Armstrong on March 26, 1781: “We ought not to look back, unless it is to derive useful lessons from past errors, and for the purpose of profiting by dear bought experience. To inveigh against things that are past and irremediable, is unpleasing; but to steer clear of the shelves and rocks we have struck upon, is the part of wisdom.”38 But he did not want to talk about himself. In a letter to his lifelong personal friend and favorite physician, Dr. James Craik on March 25, 1784:

I will frankly declare to you, my dear doctor, that any memoirs of my life, distinct and unconnected with the general history of the war, would rather hurt my feelings than tickle my pride whilst I lived. I had rather glide gently down the stream of life, leaving it to posterity to think and say what they please of me, than by any act of mine to have vanity or ostentation imputed to me. I do not think vanity is a trait of my character.39

In his past as well as in his future conduct, he strove to avoid vanity. In a letter to James Madison, written from Mount Vernon, May 20, 1792, he pointed out that given the existing political divisions, it would be best for the country for him to run for president again, but that he was not seeking reelection for vanity’s sake, but for the good of the nation. He hoped no one would misinterpret his motives:

Nothing short of conviction that my deriliction of the Chair of Government (if it should be the desire of the people to continue me in it) would involve the Country in serious disputes respecting the chief Magestrate, and the disagreeable consequences which might result there from in the floating, and divided opinions which seem to prevail at present, could, in any wise, induce me to relinquish the determination I have formed: and of this I do not see how any evidence can be obtained previous to the Election. My vanity, I am sure, is not of that cast as to allow me to view the subject in this light.

....In revolving this subject myself, my judgment has always been embarrassed. On the one hand, a previous declaration to retire, not only carries with it the appearance of vanity and self importance, but it may be construed into a manoeuvre to be invited to remain. And on the other hand, to say nothing, implys consent; or, at any rate, would leave the matter in doubt, and to decline afterwards might be deemed as bad, and uncandid.40

When he wrestled with the question of becoming the president for the first time at Mount Vernon, one of his favorite military aids had been staying with the Washingtons. David Humphreys became the president’s confidant in those interesting days, and in his unfinished biography, he preserved some of the discussions that the two had about Washington’s pending history making decision. Out of this trust, Humphreys was given Washington’s go ahead to work on his biography, a project he never finished.41

HIS OFFICIAL BIOGRAPHY?

He also pointed out that he neither had the time—nor the literary skills—to write up a memoir about his war experience. Below is a comment he made in a letter to David Humphreys, the only man Washington would trust to write a biography of him, dated July 25, 1785:

If I had the talents for it, I have not leisure to turn my thoughts to Commentaries [on the Revolutionary War]. A consciousness of a defective education, and a certainty of the want of time, unfit me for such an undertaking.42

Unfortunately, Humphreys did not finish the task before his death. Yet, of the several chapters he wrote, some of them have been found recently and have been used in our study of Washington.

Meanwhile, Washington perhaps had a little fear about even Humphreys’ undertaking such a task, because he did not want to be unduly praised. The retiring president wrote his French friend, Marquis de Chastellux:

Humphreys (who has been some weeks at Mount Vernon) confirm’d me in the sentiment by giving a most flattering account of the whole performance: he has also put into my hands the translation of that part in which you say such, and so many hand some things of me; that (altho’ no sceptic on ordinary occasions) I may perhaps be allowed to doubt whether your friendship and partiality have not, in this one instance, acquired an ascendency over your cooler judgment.43

A significant aspect of this letter is Washington’s parenthetical aside: “altho’ no sceptic on ordinary occasions.” His temperament was not normally marked by doubt. Although not a skeptic, and thus not of a temperament that would dispose him to philosophical doubt and unbelief, this does not mean that Washington was a stoic who could not laugh or enjoy the humor of life.

SENSE OF HUMOR

George Washington is often portrayed as if he did not have a sense of humor but that too is inaccurate. As Zall says:

Just as credible, because evident also in his writings, Washington’s stony countenance could dissolve before “an unaffected sally of wit.” Congress excused its failure to provide funds because treasurer Robert Morris had his hands full. Washington replied that he wised Morris had his pockets full. When Mrs. Washington chided him for saying grace before dinner with a clergyman at the table, Washington pardoned himself: “The reverend gentleman will at least be assured that at Mount Vernon we are not entirely graceless.44

And Zall writes further:

Natural versus contrived wit bubbles up in writing meant for his eyes only. . . .His diary has such entries as the one recording a Sunday service in York, Pennsylvania. The town lacked an Episcopalian preacher, so Washington attended a Pennsylvania Dutch Reformed church. Since the service was in German and he had understood not a word, he reassured the diary, he had not been converted.45

Occasionally Washington even indulged in a bit of sarcasm in the privacy of his diary. He once commented on two sermons he heard while traveling, “I attended Morning & evening Service, and heard very lame discourses from a Mr. Pond.”46 He also critiqued the meager refreshments and decorations of a ball in Alexandria. His diary dubbed it the “bread and butter ball.”47 Zall notes another example of such sarcastic humor, this time aimed at himself:

Private correspondence also reveals the Washington wit. Former neighbor Eliza Power writes from Philadelphia that the desk he had left behind had a secret drawer containing love letters. He replied that if she had found warmth in those letters, she must have set them afire.48

More than a century before Mark Twain quipped “the reports of my death are greatly exaggerated,” Washington noted that the word of his death was premature. After a battle during the French and Indian War, where Washington survived a massacre, he wrote his brother, John Augustine, July 18, 1755:

Dear Brother, As I have heard, since my arrival at this place, a circumstantial account of my death and dying speech, I take this early opportunity of contradicting the first, and of assuring you, that I have not as yet composed the latter.49

Washington’s humor could express itself with playful parody of religious themes50 or in simply giving a description of his daily life.51

DEEP PASSIONS UNDER DISCIPLINED CONTROL

Zall writes of an incident after the War where Washington allowed his normally well-concealed emotions to be visible to his brothers-in-arms. At the war’s end, he bid farewell to officers in New York. Impulsively, he embraced each one by rank, from rotund Henry Knox on down, while “tears of deep sensibility filled every eye.”52

An emotional man at bottom, Washington, the seemingly frosty hero, was capable of the grand, dramatic gesture. His farewell to these officers, on December 4, 1783, at Fraunces’ Tavern in New York, was a scene out of a classic play. Standing before the men he had commanded for eight perilous and finally triumphant years, his customary self-control deserted him. Tears filled his eyes as he stood up, filled a glass with a shaking hand, and said in a trembling voice: “I cannot come to each of you to take my leave, but shall be obliged if you will each come and shake me by the hand.” Silently they lined up and shook his hand. Then he returned home to Mount Vernon, journeying through communities that moved him deeply with their outpourings of homage, determined to retire from public life. He had started his military career more than thirty years back, and now that he had won independence for his country the American Cincinnatus, as the newspapers and the orators called him, felt that he merited retirement to the plow. He was only fifty-one and, as he wrote to his friend Lafayette, his sole desire was to be a private citizen, sitting under his “own vine and fig-tree” and “move gently down the stream of life until I sleep with my fathers.”53

The most open expression of Washington’s deep emotions appeared in his General Orders of April 18, 1783, when he publicly declared the ending of hostilities:

...Although the proclamation before alluded to, extends only to the prohibition of hostilities and not to the annunciation of a general peace, yet it must afford the most rational and sincere satisfaction to every benevolent mind, as it puts a period to a long and doubtful contest, stops the effusion of human blood, opens the prospect to a more splendid scene, and like another morning star, promises the approach of a brighter day than hath hitherto illuminated the Western Hemisphere; on such a happy day, a day which is the harbinger of Peace, a day which compleats the eighth year of the war, it would be ingratitude not to rejoice! it would be insensibility not to participate in the general felicity.

The Commander in Chief far from endeavouring to stifle the feelings of Joy in his own bosom, offers his most cordial Congratulations on the occasion to all the Officers of every denomination, to all the Troops of the United States in General, and in particular to those gallant and persevering men who had resolved to defend the rights of their invaded country so long as the war should continue. For these are the men who ought to be considered as the pride and boast of the American Army; And, who crowned with well earned laurels, may soon withdraw from the field of Glory, to the more tranquil walks of civil life.

While the General recollects the almost infinite variety of Scenes thro which we have passed, with a mixture of pleasure, astonishment, and gratitude; While he contemplates the prospects before us with rapture; he can not help wishing that all the brave men (of whatever condition they may be) who have shared in the toils and dangers of effecting this glorious revolution, of rescuing Millions from the hand of oppression, and of laying the foundation of a great Empire, might be impressed with a proper idea of the [dignifyed] part they have been called to act (under the Smiles of providence) on the stage of human affairs: for, happy, thrice happy shall they be pronounced hereafter, who have contributed any thing, who have performed the meanest office in erecting this [steubendous] fabrick of Freedom and Empire on the broad basis of [Indipendency] who have assisted in protecting the rights of humane nature and establishing an Asylum for the poor and oppressed of all nations and religions. The glorius task for which we first fleu to Arms being thus accomplished, the liberties of our Country being fully acknowledged, and firmly secured by the smiles of heaven, on the purity of our cause, and the honest exertions of a feeble people (determined to be free) against a powerful Nation (disposed to oppress them) and the Character of those who have persevered, through every extremity of hardship; suffering and danger being immortalized by the illustrious appellation of the patriot Army: Nothing now remains but for the actors of this mighty Scene to preserve a perfect, unvarying, consistency of character through the very last act;54

And so the very next day, April 19th, “At noon the proclamation of Congress for a cessation of hostilities was proclaimed at the door of the New Building, followed by three huzzas; after which a prayer was made by the Reverend Mr. Ganno, and an anthem (Independence, from Billings,) was performed by vocal and instrumental music.”55

Because Washington understood the power of human passions he could write: “We must take the passions of men as nature has given them, and those principles as a guide, which are generally the rule of action.”56 He ably answered the passions of his distressed and weary officers as they wrestled with the emotions of a military confrontation with Congress.57

HIS EFFORTS TO CONTROL HIS POWERFUL ANGER58

To put the word “rapture” and George Washington in the same sentence seems nearly impossible. But still waters run deep, and sometimes they burst forth with tsunami-like force. Washington biographer, John Ferling noted, “Gilbert Stuart, an artist whose livelihood depended in part on his ability to capture the true essence of his subjects, believed Washington’s ‘features were indicative of the strongest and most ungovernable passions. Had he been born in the forests,’ Stuart added, ‘he would have been the fiercest man among the savages.’”59 Zall writes,

His dignity and self-esteem were such that to a superficial observer he appeared to be cold. Actually he was emotional, tender, and capable of outbursts of violence. An iron discipline, which he imposed upon himself all his life, kept a leash on his passions. “All the muscles of his face,” Captain George Mercer, a fellow-soldier, wrote of him “[are] under perfect control, though flexible and expressive of deep feeling when moved by emotion.” His infrequent outburst of anger were legendary. On the occasions when his rigid self-control broke under stress, he was, according to a contemporary, “most tremendous in his wrath.”60

The explosion of joy at the ending of hostilities mentioned above, near the end of the war, reveals Washington’s powerful inner passions as well as his ongoing efforts to control them. But so do his infrequent explosions of anger. The fact that George Washington was “tremendous in his wrath” was confirmed by various associates. Lafayette’s recollection of Washington’s response to General Lee’s violation of his orders at the Battle of Monmouth is a case in point.61 A fellow Virginian, General Lee, disobeyed orders and called for a retreat, for which he was court-martialed. Lee remained a bitter critic of Washington to his death.62

Other occasions are worthy of note. Zall writes of an incident where President Washington had been criticized in several newspapers hostile to the cause. Thomas Jefferson related, “The presdt . . . got into one of those passions when he cannot command himself, ran on much on the personal abuse which had been bestowed on him, defied any man on earth to produce one single act of his since he had been in the govmt which was not done in the purest motives, that he had never repented but once the having slipped the moment of resigning his office, and that was every moment since, that by god he had rather be on his farm than be made emperor of the world, and yet they were charging him with wanting to be a king.”63 Further, the criticism of an old friend, Edmund Randolph, in print, tested Washington’s temper: “The president entered the parlor, his face ‘dark and lowering.’ Someone asked if he had read Randolph’s pamphlet, Vindication (1795). ‘I have,’ said Washington, ‘and, by the eternal God, he is the damnedest liar on the face of the earth!’ he exclaimed as he slammed his fist down upon the table.”64

A similar passionate outburst of exasperation and anger occurred when Washington was president in 1791, and quietly received word at dinner of St. Clair’s defeat by the Indians. According to Tobias Lear, Washington’s personal assistant, the emotionally intense episode happened after all the guests, as well as Mrs. Washington, had left the room. He relates,

The General now walked backward and forward slowly for some minutes without speaking. Then he sat down on a sofa by the fire, telling Mr. Lear to sit down. To this moment there had been no change in his manner since his interruption at table. Mr. Lear now perceived emotion. This rising in him, he broke out suddenly: “It’s all over—St. Clair’s defeated, routed; the officers nearly all killed, the men by wholesale; the rout complete—too shocking to think of— and a surprise into the bargain!” He uttered all this with great vehemence, then he paused, got up from the sofa and walked about the room several times, agitated, but saying nothing. Near the door he stopped short and stood still for a few seconds, when his wrath became terrible. “Yes,” he burst forth, “Here, on this very spot, I took leave of him: I wished him success and honor. ‘You have your instruction,’ I said, ‘from the Secretary of War; I had a strict eye to them, and will add but one word—BEWARE OF A SURPRISE! I repeat it, BEWARE OF A SURPRISE; you know how the Indians fight us.’ He went off with that as my last solemn warning thrown into his ears. And yet! To suffer that army to be cut to pieces, hacked, butchered, tomahawked, by a surprise—the very thing I guarded him against! O God, O God, he’s worse than a murderer! How can he answer it to his country? The blood of the slain is upon him—the curse of the widows and orphans—the curse of Heaven!”65

A TENDER-HEARTED FRIEND

As a young man, George Washington expressed his joy in friendship and admitted to the power of passion. Both of these occurred in an early letter describing a teenage romance, and his “chaste” struggles to control his “passion.” Writing to “dear friend Robin” between 1749-1750 he divulges:

As it’s the greatest mark of friendship and esteem Absent Friends can shew each other in Writing and often communicating their thoughts to his fellow Companions makes me endeavor to signalize myself in acquainting you from time to time and at all times my situation and employments of Life and could wish you would take half the Pains of contriving me a letter by any opportunity as you may be well assured of its meeting with a very welcome reception. My place of Residence is at present at His Lordship’s [Fairfax]

where I might, was my heart disengaged, pass my time very pleasantly as there’s a very agreeable Young Lady Lives in the same house [Mary Cary]. But as that’s only adding Fuel to fire, it makes me the more uneasy, for by often, and unavoidably, being in Company with her revives my former Passion for your Low Land Beauty; whereas, was I to live more retired from young Women, I might in some measure alleviate my sorrows, by burying that chaste and troublesome passion in the grave of oblivion or eternal forgetfulness, for as I am very well assured, that’s the only antidote or remedy that I shall be relieved by or only recess that can administer any cure or help to me, as I am well convinced, was I ever to attempt anything, I should only get a denial which would be only adding grief to uneasiness.66

Friendships mattered to Washington. His inner self was reserved for those who were closest to him. These individuals sometimes received very striking personal revelations in his letters. Moreover, to be his friend was to experience sincere affection, a warm welcome and a hearty embrace. But to become Washington’s friend was no easy matter. This seems to reflect his classic “Rules of Civility” number fifty-six that speaks of exercising great care in choosing friends: “Associate yourself with men of good quality, if you esteem your own reputation; for it is better to be alone than in bad company.” How to choose a friend was one of the matters of wisdom he sought to impart to his young namesake and adopted grandson, George Washington Parke Custis. Writing from Philadelphia on November 28, 1796, he counseled,

...select the most deserving only for your friendships, and before this becomes intimate, weigh their dispositions and character well. True friendship is a plant of slow growth; to be sincere, there must be a congeniality of temper and pursuits. Virtue and vice can not be allied; nor can idleness and industry....67

But when an intimate friendship was established, Washington allowed his closest friends to experience his deep emotions through open and generous expressions of love. Lifelong friendships were made by Washington with neighbors such as Scotch-Irish Presbyterian Dr. James Craik68 and the Anglican/Episcopalian clergyman, the Reverend Lord Bryan Fairfax.69 In Washington’s adult life, close friendships formed within the circle of his fellow military officers Marquis de Lafayette,70 Comte Rochambeau,71 Marquis de Chastellux,72 Baron Von Steuben,73 Comte DeGrasse,74 military aide David Humphreys,75 Colonel Alexander Hamilton,76 and General Henry Knox.77 There was, however, an especially tender place in Washington’s heart for the Marquis de Lafayette. Consider these endearing words of affirmation in his letters to his twenty-five-year-younger, surrogate son:

...the sincere and heartfelt pleasure that you had not only regained your liberty; but were in the enjoyment of better health than could have been expected from your long and rigorous confinement; and that madame La Fayette and the young ladies were able to Survive ...amongst your numerous friends none can offer his congratulations with more warmth, or who prays more sincerely for the perfect restoration of your ladies health, than I do.78

Washington’s cool yet gracious countenance was the necessary firewall to contain and to protect his passionate heart.

CONCLUSION: THE LANGUAGE OF WASHINGTON’S HEART

Just as there are largely unknown statements of faith etched on the stairway walls of the Washington Monument as one mounts the stairs to the pinnacle, so inside the marble-like exterior of Washington there was a largely unknown heart of deep feelings, strong emotions, and a reverent personal faith. As he wrote from New York, just at the end of the War to the freeholders and inhabitants of Kings County on December 1, 1783, “...you speak the language of my heart, in acknowledging the magnitude of our obligations to the Supreme Director of all human events.”79 Just as access to the stairs of the monument is restricted, precluding the average American from reading the marvelous testimonials to the faith etched there, so too, many modern historians have cut off access to the real Washington. This book will reopen the stairs, so to speak, to Washington’s soul and we will once again read the language of his heart etched throughout his life, which was the language of a deep faith, expressed by a devout Christian in the eighteenth century Anglican tradition. Indeed, the language of Washington’s heart was warmed by his passionate soul and the “sacred fire of liberty.”