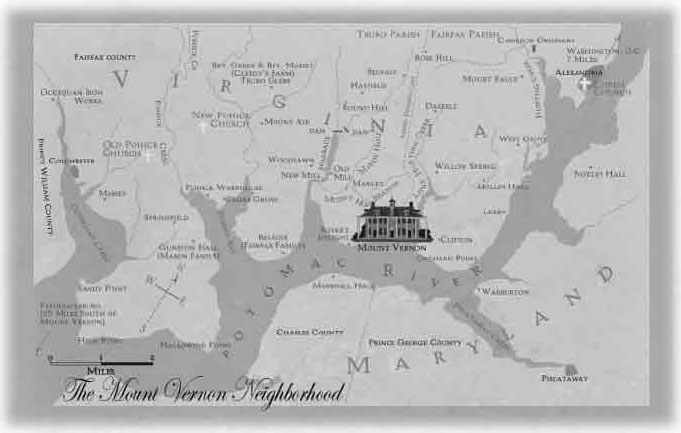

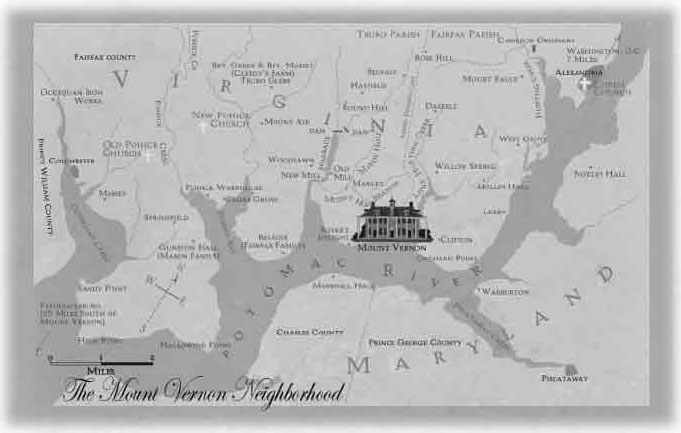

For years, Washington was a lay-leader (a vestryman, so named because of the vestments they wore) in the Church of England in the Truro Parish in northern Virginia, outside of the city we now call Washington, D.C. The significance of Truro Parish for our nation’s existence is immense. Dr. Philip Slaughter, historian of Truro Parish, explains,

No Parish in the Colony had a Vestry more distinguished in its personnel, or more fully qualified for their positions, than the Parish of Truro. . . Eleven of them sat at various times in the House of Burgesses. Two of them, the Fairfaxes, were members of “His Majesty’s Council for Virginia.” Another of her vestrymen was George Mason, one of the first among the founders of the State and the great political thinkers of his age; while still another was declared to be the “Greatest man of any age,” the imperial George Washington.2

The role of the vestryman in colonial Virginia was captured by Thomas Jefferson,

Usually the most discreet farmers, so distributed through their Parish that every part of it may be under the eye of some one of them. They are well acquainted with the details and economy of private life, and they find sufficient inducements to execute their charge well in their philanthropy, in the approbation of their neighbors, and the distinction which that gives them.3

The vestry book begins with a citation of the Act of the General Assembly that created the parish along with a record of the election of the members and the proceedings of their first meeting. This Act required that the sheriff of the county call the freeholders and housekeepers, to assemble to elect the “most able and discreet persons in the said Parish as shall make up the number of vestrymen in the said Parish twelve and no more.”4 Thus, the first vestry met in 1732, when George was about one year old. At that meeting, five vestrymen were elected, “having taken the oaths appointed by law, and subscribed to be conformable to the doctrine and disciple of the Church of England.” Truro Parish took its name from the parish in Cornwall, England, which became the Diocese of Truro.

There are those who have argued that Washington’s service in the vestry of the Anglican Church of Virginia really has little to do with his personal faith. For after all, it was a political position of prestige. And even Thomas Jefferson, hardly a strong role model for devout Christians, was elected as a vestryman.5 Author Paul Boller, Jr. is one such example. But there is a dramatic difference between vestryman Washington in the Truro Parish and vestryman Jefferson in St. Anne’s Parish that “passes through Charlottesville.”6 While Bishop Meade affirms that Jefferson was “elected to the vestry of St. Anne’s,” he adds, “though it does not appear that he ever acted.”7 To be merely elected a vestryman did not make one a “churchman.”

Paul Boller, for instance, writes, “it is not possible to deduce any exceptional religious zeal from the mere fact of membership—even Thomas Jefferson was a vestryman for a while.”8 He also added, “...it is impossible to read any special religious significance into his service.”9

But Washington’s long and faithful service stands in marked distinction from Jefferson’s mere election. Washington actually served with great fidelity. We do not want to read anything into this other than what the facts tell us, and the facts are that George Washington’s service as a vestryman is commensurate with the highest commitment to the Christianity proposed by the Anglican Church. George Washington’s service as a vestryman is summarized by Philip Slaughter,

The regularity of Washington’s attendance at the meetings of the Vestry is deserving of special notice. During the eleven years of his active service, from February, 1763, to February, 1774, thirty-one “Vestries” were held, at twenty-three of which he is recorded as being present. On the eight occasions when he was absent, as we learn from his Diary or other sources, once he was sick in bed, twice the House of Burgesses, of which he was a member, was in session, and three other times certainly, and on the two remaining occasions probably, he was out of the County.10

Washington’s commitment to service to the church was exemplary, even by modern standards, when we have faster and more convenient means of transportation.

What did it require to be a vestryman? If public surveyors were required to take oaths to serve,11 it was even more logical that those entrusted with the church sanctioned by the state would take oaths as well. George’s father, Augustine, had assumed the office of vestryman on November 18, 1735, when George, his first-born son by his second marriage, was only three years old. The oaths required of a vestryman for both Augustine Washington and his son George were the same: “I, A B, do declare that I will be conformable to the Doctrine and Discipline of the Church of England, as by law established.” This meant that they declare their faith in the key Christian doctrines, including the divinity of Christ, Christ’s death for sinners, and his resurrection from the dead.

Having been elected to the vestry of Truro Parish on October 25, 1762, some thirty years after his father, George took the same oath on February 15, 1763. The vestry book of Truro Parish has the following record: “Ordered, that George Washington, Esq. be chosen and appointed one of the vestrymen of this parish, in the room of William Peake, Gent. Deceased.”12 The Records of the County Court of Fairfax has under the date of February 15th, 1763, “George Washington Esqr. took the oaths according to Law repeated and subscribed the Test and subscribed to the Doctrine and Discipline of the Church of England in order to qualify him to act as a Vestryman of Truro Parish.”13 Speaking of the oaths taken by vestrymen, Slaughter writes, “they were oaths of allegiance and of abjuration of Popery and of the Pretender, etc., and were required of all Civil and Military officers by the laws of England and of Virginia. . . It seems to have required as many as six oaths and subscriptions properly to qualify a Vestryman in those days.”14

THE HISTORY OF TRURO PARISH’S VESTRY

The history of the vestry is significant to appreciate Washington’s role as a churchman. One of the initial duties the vestry had, when a new parish began, was to organize and build churches. So in 1733, the Reverend Lawrence De Butts was called to preach three times a month in various churches, one of those times being “at Occoquan Church,” which was the name for the “old Pohick Church.” His salary was to be “the sum of eight thousand pounds of tobacco, clear of the Warehouse charges and abatements.”15

Along with building churches and filling pulpits, the vestry had the duty to secure and to provide for the clergy of the established church. It was the practice for each Anglican church to have a farm. These were called glebes. Thus, one of the responsibilities of the vestry was to provide for these glebes. The Truro Parish glebe began in 1734.16 Because there were insufficient clergy for the pulpits, the vestry also hired readers. As their name implies, they were to read published Anglican sermons at services and read prayers from the Book of Common Prayer.17 Some of the sermons that would have been read were the Anglican homilies, these are listed in the Thirty-Nine Articles, the official confession of faith of the Anglican Church. The need for a resident clergyman was immediately apparent, and in 1734 the vestry began a search for a pastor.18

Seventeen-thirty-five was the first year that a Washington family member served on the Truro Parish. On November 18th, the record states, “Augustine Washington gent. being this day sworn one of the members of this Vestry, took his place therein accordingly.”19 The early history of Augustine Washington’s vestry shows that the vestrymen in Virginia were serious in their work, as they sought to honor the Anglican heritage and adapt it to the colonial context.

VARIOUS DUTIES OF THE VESTRY

Along with the many duties of the vestry in regard to church building and caring for the clergy, there were also the responsibilities to care for the poor, to protect the historic boundaries of lands, to collect tithables or church taxes, and to prevent and discipline moral violations.

Caring for the poor was especially the duty of the one who occupied the office of Church Warden. His duties included “binding orphan and other indigent children as Apprentices” and imparting “...the duties and morals of those apprenticed, their being taught to read English and the ‘Art and mystery’ of shoemaking, or of a Carpenter...”20

An ancient vestry duty continued in Virginia was the custom of renewing landmarks. This was termed “processioning.” Every four years, landowners in good standing were appointed by the vestry to “perambultate” the parish, going around the plantations and assuring the boundaries were still well marked.21

Since tobacco was the primary means of exchange for much of colonial Virginia, church funds were likewise paid by the crop. In order to raise the tobacco to pay for the glebe and its mansion house, as well as its resident rector, not to mention the general care and building of the churches themselves, a great deal of tobacco had to be collected. Records not only had to be kept, but the law complicated the collections by further specifying which persons were “tithables” or countable in a collection of the tithe on tobacco for the church’s many needs.

All male persons of the age of sixteen years or upwards, and also negro, mulatto and Indian women of like age, (“except tributary Indians to this government,”) were “tithable” or chargeable for county and parish levies. But the Court or vestry, “for reason of charity,” could excuse indigent persons from payment, and this was frequently done. In 1733 there were 676 tithables in Truro. Ten years later there were 1,372. This indicates the growth of the population. The Parish Levy varied widely year by year, the average being about 34 pounds of tobacco per poll.22

In view of these extensive financial and legal vestry duties, it is understandable why the records also show payments to a vestry clerk to keep the records, to collectors to secure the tithes, and to a church sexton to maintain the property and to bury the dead.

GEORGE WASHINGTON AS VESTRYMAN

Nearly twenty years would pass after Augustine’s death until George, at the age of thirty, would follow in his father’s footsteps and become a vestryman himself in 1762. During this time, the life of the parish quietly continued with some important intervening events.

In 1742, a new county was created out of Prince William County and was named Fairfax County. The boundary line of Truro Parish and the new county coincided.23 In 1748, an Act of Assembly established in the new county a town named Alexandria. This city was named for the three Alexander brothers, John, Robert, and Gerard, who had emigrated from Scotland and had there established tobacco warehouses, which had been known before its new name as Hunting Creek Warehouse or Belle-Haven. As early as June 4, 1753, the Reverend Charles Green had been preaching there every third Sunday.24

Given the presence of these Scottish businessmen, Alexandria also became a center for Presbyterian settlers, and a strong Presbyterian church community was established. Coming from these Presbyterian settlers was another of George Washington’s closest life-long friends, Dr. James Craik. Dr. Craik was Washington’s close friend, travel partner, army surgeon general, and personal physician. He was present when Washington died.

What responsibilities were church wardens charged with? In part, they were the protectors of public morals. As Reverend Slaughter states in the The History of Truro Parish,

Among the duties of the Church Wardens was that of presenting to the Court of the county persons guilty of gambling, drunkenness, profanity, Sabbath breaking, failing to attend church, disturbing public worship, and certain other offences against decency and morality. The fines imposed in these cases went to them for the use of the Parish, and sometimes mentioned in the annual statement, though usually they would be included in the Wardens account which are not given in detail. That the Church Wardens of Truro, Cameron and Fairfax Parishes did not fail in their duty of presenting offenders is abundantly shown in records of the county Court. Presentments were usually made through the Grand Jury, the offender’s Parish being designated, but sometimes the Church Wardens themselves are named as prosecutors.25

Washington was Church Warden in 1764, a year that saw some large changes in the Parish. One of his duties was to auction tobacco at the court house for the vestry, which is described in the vestry minutes,

Ordered that 31,549 lb. of tobo. In the hands of the Church Wardens for the year 1764, to wit, George Washington and George Wm. Fairfax Esqrs. be sold to the highest bidder, before the Court House door of this County on the first day of June Court next between the hours of 12 and 4, and that publick notice be given of the sale.26

One of the issues that occurred at this time was another division of Truro Parish, creating a new Fairfax Parish and the older continuing Truro Parish. Each Parish was to elect its vestry. But the result of the division was not well received by the continuing Truro Parish. Ultimately, the conflict boiled down to an equitable distribution of “tithables.” The issue had to be resolved by the House of Burgesses.

Washington was caught in the middle of the conflict. Again Reverend Slaughter notes:

It is evident that Washington himself, and his immense estate at Mount Vernon, was the principal bone of contention between the mother and daughter Parishes. The lines proposed ran, the one on the south, the other on the north, of the estate. The one finally adopted divided it leaving far the larger part, however with the mansion house, in Truro. That he would take an active interest in the settlement of the question was inevitable, and doubtless his direct agency is to be seen in the compromise petition which found favor with the House of Burgesses and was the basis of their legislation. The Act which was passed may well have been drawn by his own pen. In contrast with the previous Act it is unusually specific in its details, and would seem to indicate the hand of the Surveyor in its clearly described lines, and of the Church Warden in its accurate enumeration of the property and assets of the Parish.27

Another reference revealing Washington’s interest in this matter is a manuscript where he lists the results of both the vestry elections in March and the elections in July. It was confusion over seeing Washington’s name listed as elected in both that created the misunderstanding that he had been elected to and served in two vestries. Those historians today that deny Washington was a Christian ignore his deep commitment to serving the church. His keen interest in the church is seen by the fact that he was elected to serve in two separate parishes. When the parish he served in was ended and another started, he was immediately willing to serve in the new and was elected a second time.

Slaughter writes:

This paper shows that at the first election, in March, 1765, Col. Washington was elected a Vestryman of the first Fairfax Parish, he being, for the moment, a resident therein. The life of this Parish was exactly four months, and of this Vestry-elect two months and three days, even if its members never qualified or met for organization, of which there is no evidence. In July, Mount Vernon having, in the meantime, been restored to Truro, Col. Washington was again elected a Vestryman of Truro Parish, and was not eligible in any other.28

The result of the division was far more equitable since the result was 1,013 tithable in Fairfax Parish and 962 in Truro. But the good news of a successful division of the Parish was soon dampened when the Reverend Charles Green died.

Charles Green’s death had a significant impact on Washington. He lost a physician, since his letters reveal that there were times when his pastor also provided medical care, such as the time he wrote for a house call when he was in such pain he could scarcely write the letter, or when Mrs. Washington had contracted the measles.29 He also wrote to him from the Warm Springs, describing the location and potential health benefits.30 He clearly lost a long-standing friend from the days of his father’s service on the vestry. But the passing of “Parson Green,”31 as he called him on one occasion, also meant that he and the other vestrymen would have to search for another clergyman for Truro Parish.

The regular duties of the parish did not cease with the passing of Reverend Green. On February 3-4, 1766, Washington and fellow vestrymen determined to build a new church, and Washington was appointed to the building committee of this church.32 As the contract was signed for this construction project, an attorney named Lee Massey was present and served as a witness. But he also served the vestry in another important way. The vestry record of the same meeting states,

Whereas Mr. Lee Massey, an Inhabitant of this parish, having this day offered to supply the place of a Minister therein, and the Vestry being of opinion that he is a person well qualified for the sacred function, have agreed to recommend him to the favour of His grace the Bishop of London and of the Governor of this Colony, for an Introduction to this said parish, and to receive him upon his return properly qualified to discharge the said office.

In consequence of the aforesaid Resolve a Recommendation to his Lordship the Bishop of London, and an address to his Honour the Governor of this Colony in favour of Mr. Lee Massey being made out, are ordered hereafter to be recorded.33

Washington was present at this meeting, and, as can be seen from the minutes, he signed the letters that were sent to the Bishop and the Governor. Thus, with the approval of Church Warden George Washington, the well-respected Lee Massey was authorized to travel to London for Anglican ordination and thus take his first step to become the new minister of Truro Parish.

GEORGE WASHINGTON ON THE POHICK CHURCH BUILDING COMMITTEE

In 1767, Washington again served as Church Warden. In this very busy year for the parish, he saw the return and reception of the newly ordained Reverend Lee Massey as the new Minister of Truro Parish. He also was responsible for the oversight of the building of the Falls Church and its vestry house, the sale of the old glebe, and the accounts of the sale of the church’s tobacco and of the payments to the parish’s employees. But something even more dramatic happened at the annual meeting on November 20, which met to discuss the amount of Parish “tax.” This tax or levy was the assessment to be raised from the church members to build new churches and to operate the existing churches. In a vote that included every member of the vestry, since all were present, there was a split vote concerning the building of another new Church.

Resolved, that a Church be built at or as near the Cross Road leading from Holis’s to Pohic Warehouse as water can be had, which resolution was carried by a majority of seven to five.34

A tradition has come down from this meeting that was first given by Washington biographer Jared Sparks in his Life of Washington and has been repeated by many others, including Bishop Meade.

The Old Pohick Church was a frame building, and occupied a site on the south side of Pohick run, and about two miles from the present site which is on the north side of the run. When it was no longer fit for use, it is said the parishioners were called together to determine on the locality of the new Church, when George Mason, the compatriot of Washington, advocated the old site, pleading that it was the house in which their fathers worshipped, and that the graves of many were around it, while Washington and others advocated a more central and convenient one. The question was left unsettled, and another meeting for its decision appointed. Meanwhile Washington surveyed the neighborhood, and marked the houses and distances on a well-drawn map, and, when the day of decision arrived, met all the arguments of his opponent by presenting this paper, and thus carried his point.35

Pohick Church still stands today. You can visit it in Lorton, Virginia. As of this writing, the Reverend Donald S. Binder, Ph.D., serves as the rector. He notes:

Washington surveyed the land. He actually argued to have the church moved here because it was a more centralized location, had a surveyor’s map, drawn up so he could win the point with the rest of the vestry, and so the church was moved up here. It’s also on very high ground; you can really oversee the whole of Lorton Valley down below and so, he thought it was an appropriate place, to put a church, you know, closer to heaven, more or less, is the thinking.36

The old site was closer to Mason’s estate, Gunston Hall, while the new site was closer to Washington’s Mount Vernon. The first meeting may have occurred at the September 28, 1767, vestry, where four vestrymen were absent although Mason and Washington had been there. The strong opinions expressed on the location seem to be supported by the full attendance of the vestry at its next meeting, and the close 7-5 vote in favor of Washington’s location. It is easy to overlook how important the church’s life was in this era. At times the churchyard itself was the venue for important discussions and decisions regarding the future of America.37 It is certainly fascinating to consider that here we find neighbors, Mason and Washington, two statesmen who would become critical to the foundations of a new nation, debating over the location of their church building. Clearly, church and state were important concerns for our Virginian founding fathers. The building committee for the new Pohick Church included both Washington and Mason, which seems to indicate that their debate and its ultimate outcome did not end their ability to work together.

Washington’s commitment in serving the church was time-consuming. He spent many hours at these long meetings serving the vestry. An exceptionally long meeting occurred on March 3, 1769. Washington’s diary confirms the vestry record: “Mar. 3d. Went to a Vestry at Pohick church and returned abt. 11 o’clock at night.”38

GEORGE WASHINGTON’S FINAL VESTRY MEETING

With the arrival of 1774, Washington’s national leadership was to become a reality, and with it came the necessity to relinquish actual leadership in his local parish’s vestry, even though he was once again appointed Church Warden for the next year, 1775. His final meeting as an active vestryman makes clear that he did not leave his church with a spirit of indifference or unbelief. The last vote that he actually participated in says,

Ordered that the new Church near Pohic be furnished with a Cushion for the Pulpit and Cloths for the Desks & Communion Table of Crimson Velvett with Gold Fring, and that Colo. George Washington be requested to import the same, as also two Folio Prayer Books covered with blue Turkey Leather with name of the Parish thereon in Gold Letters, the Dimensions for the said Cushion and Cloths being left to Wm. Bernard Sears who is desired to furnish Colo. Washington with proper Patterns at the Expense of the Parish.39

The vestry adjourned to meet the next day, February 25th. The record states, “Bonds being taken yesterday from Colo. George Washington for himself, and also as Attorney in Fact for Colo. George William Fairfax, now in Britain, . . .”40

George remained a nominal vestryman until he resigned in 1782, at the end of the war. His public duties from this time on made it impossible for him to serve in any active way on the Truro Vestry. For example, on July 10, 1783, he wrote to his old friend and former vestryman, George William Fairfax, then residing in London, “I have not been in the State (Virginia) but once since the 4th of May, 1775. And that was at the siege of York. In going thither I spent one day at my own house, and in returning I took 3 or 4, without attempting to transact a particle of private business.”41 In 1784, two years after General Washington resigned, Lund Washington was elected to the vestry in 1784, thus keeping a Washington on the vestry.42

But Washington’s absence from the vestry and the church at Pohick did not end his influence or his interest. He provided funds for expensive decorations for the church that were done in gold leaf.43

NO MORE STATE FUNDS FOR THE CHURCH

When the eventful year of 1776 arrived, there was a profound impact on the parish. Eventually, there would be no state support for the church, which became a final reality in 1786 with Disestablishment. The clergy would now have to be supported by the voluntary contributions of the church. With George Fairfax in England and General Washington leading the Continental Army, the needs of the Truro Parish became so great, that Reverend Massey ceased to preach and began to practice medicine. (Reverend Massey was first a lawyer, then a pastor, and lastly a physician.) The inherent tension between his vow to the King and his loyalty to his congregation may have played a major role as well, given the fact that he concluded his practice of law because of his disdain for moral tension in many of the cases he had to address as an attorney.

The duties of leading an army away from his financial base of plantation life also made it a challenge for George Washington to honor his substantial commitments. His obligations for the Pohick pews also included that of his friend George William Fairfax, who returned to England before the hostilities of arms broke out. On November 22, 1776, the vestry book states,

Mr. Peter Wagener and Mr. Thomazen Ellzey appointed Church Wardens, and ordered to receive from former Wardens all balances due the Parish, including General George Washington’s Bond and that of Col. George William Fairfax for which the General is liable, and to pay the several sums due the Parish Claimants charged this day, amounting to 119 pounds six shillings and four pence.

While it is clear that Washington did not serve as a vestryman in two parishes, although elected to serve in two, it is also clear that Washington determined to have a family pew in both the new Fairfax Parish and the continuing Truro Parish. This may have been an expression of love for the new Christ Church that was being built in Alexandria at the same time as the new church was being built in Pohick, or it may have been due to a sense of duty, since his Mount Vernon estate had been divided between the two parishes by the final redistricting of the new parish. It is even possible that the earlier tensions that had occurred within the vestry over the placement of the Pohick Church, coupled with the departure of his friend George William Fairfax, and the physical infirmities of Lee Massey, were motives for George to have a pew in Christ Church.

What we do know is that Washington paid the highest individual price for the pews that he purchased in both of the new churches, even more than Robert Alexander, for whom the new city had been named. At Pohick, his bid tied that of George Fairfax, for which George became personally liable when the Fairfaxes quietly fled the country in the face of the looming revolution.44

The pew Washington purchased at Christ Church still exists and is in the front on the left, with a close view of the Communion table and altarpiece with the Creed, Commandments, and Lord’s Prayer. This pew is doubly historical, since Gen. Robert E. Lee later occupied it.45

WASHINGTON’S DEEP INTEREST IN THE CHURCH PEWS

Insight into Washington’s deep interest in the pew at Christ Church Alexandria is evident in one of the most passionate letters that he ever wrote. For some reason the vestry in the new Fairfax Parish was considering the setting aside of the sale of the pews—which would have been unfair to those (such as Washington) who had already paid goodly sums for such pews. Since Washington was not a vestryman in Fairfax Parish, he had not had a role in this decision. But when he heard that this was under consideration, he wrote a scathing letter in protest. The letter to the vestry is to the attention of John Dalton and is dated February 15, 1773. It was written from Mount Vernon and it shows that Washington’s interest in the pew was not a mere show of religiosity or cultural duty.

Sir: I am obliged to you for the notice you have given me of an intended meeting of your Vestry on Tuesday next. I am an avowed Enemy to the Scheme I have heard (but never till of late believed) that some Members of your Vestry are Inclined to adopt.

If the Subscription to which among others I put my name was set on foot under Sanction of an Order of Vestry as I always understood it to be, I own myself at a loss to conceive, upon what principle it is, that there should be an attempt to destroy it; repugnant it is to every Idea I entertain of justice to do so; ... As a Subscriber who meant to lay the foundation of a Family Pew in the New Church, I shall think myself Injured; ... as every Subscriber has an undoubted right to a Seat in the Church what matters it whether he Assembles his whole Family into one Pew, or, as the Custom is have them dispers’d into two or three; ...

...considering myself as a Subscriber, I enter my Protest against the measure in Agitation. As a Parishioner, I am equally averse to a Tax which is intended to replace the Subscription Money. These will be my declared Sentiments if present at the Vestry; if I am not I shall be obliged to you for Communicating them, I am, etc. 46

In no uncertain terms, Washington was decrying the proposal that the vestry of Fairfax County reallocate the church pews, even if he were repaid his subscription money. He had intended to establish a family pew. This vestry action would have removed the family spiritual legacy that George Washington had planned to create. This powerful missive apparently carried the day, since his family pew was awaiting him after the war, when he began his regular attendance in Alexandria, sometime around April 1785.

Washington’s place in the church clearly mattered to him. Scarcely any other letter in all of George Washington’s writings carries the passion he displays in the above letter for his place in the church.

CONCLUSION

When we think of George Washington, we think of a great leader. One of the places he learned to lead was in the context of the church. The leadership principles that the father of our country put into practice in the army, in presiding over the Constitution, and in the presidency were learned in part in the service to his church.

It should be abundantly clear that not only did the church play an important part in Washington’s life, but Washington played an important role in the church as well. The record reveals a faithful and intense commitment of Washington to his churches, far beyond what one might expect from a Deist.

There were substantial requirements for a serious vestryman. He had to affirm the creed of the Anglican Church, which at that time was orthodox Christianity. Did it cost anything in terms of time, energy, and emotion to be more than a figurehead vestryman like Thomas Jefferson? The answer is that it cost a great deal, especially in an intensely busy life like Washington’s. Yet, his commitment to his church was not just the highest price for a pew and gold leaf for the sanctuary, but it was consistent attendance at meetings that sometimes went into the wee hours of the unlit, dark, colonial Virginia nights. Boller’s mistake is to assume that Washington’s activity in the vestry did not reveal any special religious zeal. That assumption is not only refuted by the bare recital of the facts of Washington’s vestry service in comparison with Jefferson’s inactivity, but Boller’s unsubstantiated claim also fails to hear how George Washington chose to speak most loudly and clearly to his family, friends, and neighbors. It is the same way he still speaks to posterity. Deeds not words!