Washington led his patriot army to the wintry hills northwest of Philadelphia in late December 1777, after being defeated at Brandywine (September 11, 1777) and Germantown (October 4, 1777). In so doing, he did more than secure an outpost with a strategic advantage for the work of his army. He also forged the legacy and character of his nation.

The proximity and height of the hills of Valley Forge provided surveillance of the British Army enjoying a comfortable winter in captured and civilized Philadelphia. But the sheer barrenness of the woods and fields of Valley Forge, with its raw exposure to the inclement elements, created a daily and deadly enemy for Washington’s half-naked and undersupplied army. The frigid struggle for survival by the American Army in its “sacred cause” of liberty gave Valley Forge symbolic meaning, for the winter of 1777-78 would be the lowest “valley” of American hope and morale.

Yet the struggles and doubt endured were to “forge” the character of a nation. The anvil of perseverance struck by the unyielding blows of the hammer of suffering formed not just an army. When the hope of spring was buoyed with the commitment of aid by the King of France, Washington’s army left Valley Forge with a spring in its step and a character formed in the indelible likeness of General Washington. For it was his exemplary leadership and steadfast character that kept the beleaguered patriot army from disbanding in the face of deprivation, death, and despair.

WASHINGTON WAS PRESENT WHEN AMERICA OPENED IN PRAYER

Unaccustomed as most Americans have become to the beliefs of our founders, it may be a surprise to learn that America was begun in prayer. If that’s a surprise to us, it was not to Washington, because he was there. Remembering this fact helps to explain why Washington saw his Army as the champions of a “sacred cause.”

To set the stage for Valley Forge, we need to go back a little over three years and consider America’s first step toward independence begun in Philadelphia at Carpenter’s Hall. The First Continental Congress could not meet at the Pennsylvania State House, today called Independence Hall, because their discussions were viewed as too radical for the Pennsylvania legislature, which was loyal to the King. So the local carpenters’ guild shared their newly constructed building, Carpenter’s Hall.

When the American delegates gathered, they knew why they had come—to address the crisis that had begun in Boston. But how should they go about their work? The Congress decided that its first official act would be to open in prayer.

This was not a simple decision, as can be seen in John Adams’ letter to his wife Abigail, written from Philadelphia on September, 16, 1774:

…When the Congress first met, Mr. Cushing made a motion that it should be opened with prayer. It was opposed by Mr. Jay, of New York, and Mr. Rutledge of South Carolina, because we were so divided in religious sentiments, some Episcopalians, some Quakers, some Anabaptists, some Presbyterians, and some Congregationalists, that we could not join in the same act of worship. Mr. Samuel Adams arose and said he was no bigot, and could hear a prayer from a gentleman of piety and virtue, who was at the same time a friend to his country. He was a stranger in Philadelphia, but had heard that Mr. Duche (Dushay they pronounce it) deserved that character, and therefore he moved that Mr. Duche, an Episcopal clergyman, might be desired to read prayers to the Congress, tomorrow morning. The motion was seconded and passed in the affirmative. Mr. Randolph, our president, waited on Mr. Duche, and received for an answer that if his health would permit he certainly would. Accordingly, next morning he appeared with his clerk and in his pontificals, and read several prayers in the established form; and then read the Collect for the seventh day of September, which was the thirty-fifth Psalm. You must remember this was the next morning after we heard the horrible rumor of the cannonade of Boston. I never saw a greater effect upon an audience. It seemed as if Heaven had ordained that Psalm to be read on that morning.

…After this Mr. Duche, unexpected to everybody, struck out into an extemporary prayer, which filled the bosom of every man present. I must confess I never heard a better prayer, or one so well pronounced. Episcopalian as he is, Dr. Cooper himself (Dr. Samuel Cooper, well known as a zealous patriot and pastor of the church in Brattle Square, Boston) never prayed with such fervor, such earnestness and pathos, and in language so elegant and sublime— for America, for the Congress, for the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and especially the town of Boston. It has had an excellent effect upon everybody here...2

Dr. Jacob Duché’s prayer in Carpenter’s Hall, Philadelphia given at the first meeting of the First Continental Congress in September, 1774 says,

Our Lord, our Heavenly Father, high and mighty King of Kings, Lord of Lords, who dost from thy throne behold all the dwellers upon the earth, and reignest with power supreme and uncontrolled over all kingdoms, empires, and governments, look down in mercy, we beseech thee, upon these American States who have fled to Thee from the rod of the Oppressor, and thrown themselves upon Thy gracious protection, desiring to be henceforth dependent only upon Thee.

To Thee have they appealed for the righteousness of their cause. To Thee do they now look up for that countenance and support which Thou alone canst give. Take them, therefore, Heavenly Father, under Thy nurturing care. Give them wisdom in council and valor in the field. Defeat the malicious design of our cruel adversaries. Convince them of the unrighteousness of their cause, and if they still persist in their sanguinary purpose, O let the voice of Thine own unerring justice, sounding in their hearts, constrain them to drop their weapons of war from their unnerved hands in the day of battle. Be Thou present, O Lord of Wisdom, and direct the Council of the honorable Assembly. Enable them to settle things upon the best and surest foundation, that the scene of blood may speedily be closed; that order, harmony, and peace may effectually be restored, and truth and justice, religion and piety, prevail and flourish amongst Thy people.

Preserve the health of their bodies, the vigor of their minds. Shower down upon them, and the millions they here represent, such temporal blessings as Thou seeist expedient for them in this world and crown them with everlasting glory in the world to come. All this we ask in the name and through the merits of Jesus Christ, Thy Son, our Savior. Amen.3

Washington was part of this Congressional prayer meeting. In 1875, the Library of Congress produced a placard that summarized various reports from the founders on the impact that this first prayer had on the Continental Congress. It reads,

Washington was kneeling there, and Henry, Randolph, Rutledge, Lee, and Jay, and by their side there stood, bowed in reverence, the Puritan Patriots of New England, who at that moment had reason to believe that an armed soldiery was wasting their humble households. It was believed that Boston had been bombarded and destroyed.

They prayed fervently ‘for America, for Congress, for the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and especially for the town of Boston,’ and who can realize the emotion with which they turned imploringly to Heaven for Divine interposition and—‘It was enough’ says Mr. Adams, ‘to melt a heart of stone. I saw the tears gush into the eyes of the old, grave, Pacific Quakers of Philadelphia.”4

The rumor of Boston’s destruction turned out to be false. But the next year, 1775, at the Second Continental Congress, Washington was commissioned by Congress as the commander in chief and sent to defend Boston.

VALLEY FORGE: THE CRUCIBLE OF THE “SACRED CAUSE”

And it was in Boston where Washington made his first written and public claim that the American cause was fired by a holy flame. In August 1775, a potent salvo from Washington penned to General Gage criticized the unjust treatment of American prisoners:5 “I purposely avoided all political Disquisition; nor shall I now avail myself of those Advantages, which the sacred Cause of my Country of Liberty, and human Nature, give me over you.”6 The “sacred Cause” was a theme Washington spoke of to Gov. Jonathan Trumbull7 and his officers,8 and to the president of the Congress. As General Washington wrote to the president, he concluded with a brief prayer that focused on the “sacredness of the cause”:

I trust through Divine Favor and our own Exertions they will be disappointed in their Views, and at all Events, any advantages they may gain will cost them very dear. If our Troops will behave well, which I hope will be the case, having every thing to contend for that Freemen hold dear, they will have to wade thro’ much Blood and Slaughter before they can carry any part of our Works, if they carry them at all; and at best be in possession of a Melancholly and Mournfull Victory. May the Sacredness of our cause inspire our Soldiery with Sentiments of Heroism, and lead them to the performance of the noblest Exploits.9

But it was at Valley Forge that the true cost of the sacrifice for such a holy cause would be measured. Washington wrote to John Banister, a Virginia delegate to Congress from Valley Forge on April 21, 1778.

… for without arrogance, or the smallest deviation from truth it may be said, that no history, now extant, can furnish an instance of an Army’s suffering such uncommon hardships as ours have done, and bearing them with the same patience and Fortitude. To see Men without Cloathes to cover their nakedness, without Blankets to lay on, without Shoes, by which their Marches might be traced by the Blood from their feet, and almost as often without Provisions as with; Marching through frost and Snow, and at Christmas taking up their Winter Quarters within a day’s March of the enemy, without a House or Hut to cover them till they could be built and submitting to it without a murmur, is a mark of patience and obedience which in my opinion can scarce be parallel’d.10

Only their unity, courage, and the “sacred cause” could enable the men to make the required sacrifice. As a challenge to their faith in the cause, they began their trek to Valley Forge in conformity with the Congressional Proclamation, with “thanksgiving and praise” and “…grateful acknowledgements to God for the manifold blessings he has granted us.”11 Washington’s General Orders explained:

…the General … persuades himself, that the officers and soldiers, with one heart, and one mind, will resolve to surmount every difficulty, with a fortitude and patience, becoming their profession, and the sacred cause in which they are engaged. He himself will share in the hardship, and partake of every inconvenience. To morrow being the day set apart by the Honorable Congress for public Thanksgiving and Praise; and duty calling us devoutly to express our grateful acknowledgements to God for the manifold blessings he has granted us. The General directs that the army remain in its present quarters, and that the Chaplains perform divine service with their several Corps and brigades. And earnestly exhorts, all officers and soldiers, whose absence is not indispensably necessary, to attend with reverence the solemnities of the day. (emphasis added.)12

One of the sermons preached by the chaplains on that tenuous Thanksgiving Day was by Israel Evans, Chaplain to Gen. Poor’s New Hampshire brigade.13 Printed for the army and distributed free of charge, Evans’ sermon called on the soldiers to “look on” “his Excellency General Washington” “and catch the genuine patriot fire of liberty,” “and like him, reverence the name of the great Jehovah.”14

In Chaplain Evans’ mind there was an intimate connection created by Washington between the “genuine patriot fire of liberty” and “the great Jehovah,” the one who had given his name in sacred fire at the burning bush. Washington did not read Evans’ sermon immediately. But he did read it, and when he did, he wrote to Evans on March 13, 1778:

Revd. Sir: Your favor of the 17th. Ulto., inclosing the discourse which you delivered on the 18th. of December; the day set a part for a general thanksgiving; to Genl. Poors Brigade, never came to my hands till yesterday.

I have read this performance with equal attention and pleasure, and at the same time that I admire, and feel the force of the reasoning which you have displayed through the whole, it is more especially incumbent upon me to thank you for the honorable, but partial mention you have made of my character; and to assure you, that it will ever be the first wish of my heart to aid your pious endeavours to inculcate a due sense of the dependance we ought to place in that all wise and powerful Being on whom alone our success depends; and moreover, to assure you, that with respect and regard….

Washington promised to assist Evans in advancing the sacred cause by fanning the divine fire. It was a good thing he did, because there was little else that winter at Valley Forge to keep his men warm, as the uncharming sound of the whistling, winter wind pierced the freezing ears and ragged coats of General Washington’s soldiers.

Washington’s promise to Chaplain Evans proved to be more than mere pleasantries. After his March 13, 1778, letter promising to aid the chaplain in inculcating his men’s dependence on Jehovah, Washington makes one of his clearest calls for his men to be Christians. On July 9, 1776, he had called on his men to be “Christian soldiers.”15 But on May 2, 1778, six weeks after his letter to Evans, near the end of the Valley Forge encampment, he again challenged his men to be Christians. To their “distinguished character of Patriot,” which was a high calling, since they were after all the Patriot Army,16 it was to be their “highest glory to add the more distinguished character of Christian.”17

With this command, Washington began to assist the chaplains in their “pious endeavours to inculcate a due sense of the dependence” that he thought he and his Army “ought to place in that all wise and powerful Being.”

We should note well that when Washington selected the word “inculcate,” he chose a strong word. It meant “to teach or impress by urging or frequent repetition; instill.” It is derived from the Latin word inculcare, meaning “to force upon.” The literal meaning of the word is “to trample,” or “to stomp in with one’s heel” which is evident since it combines the words “in” and “calcare,” which in turn is built on the word “calx” meaning “heel.” Apparently, Washington’s efforts became a matter of discussion that traveled outside the ranks of the camp. According to the notebook of German Lutheran clergyman, Reverend Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, it seems that Washington did more than simply issue an order about becoming a Christian. Reverend Muhlenberg wrote,

I heard a fine example today, namely that His Excellency General Washington rode around among his army yesterday and admonished each and every one to fear God, to put away wickedness that has set in and become so general, and to practice Christian virtues. From all appearances General Washington does not belong to the so-called world of society, for he respects God’s Word, believes in the atonement through Christ, and bears himself in humility and gentleness. Therefore, the Lord God has also singularly, yea, marvelously preserved him from harm in the midst of countless perils, ambuscades, fatigues, etc., and has hitherto graciously held him in his hand as a chosen vessel.18

Reverend Muhlenberg was in a significant position to know of such activity in the camp, not only because he was a pastor in Trappe, near Valley Forge, but also because he was the father of one of Washington’s generals, Reverend John Peter Muhlenberg. The Reverend General Peter Muhlenberg had also been a Lutheran pastor in Virginia, where he had known Washington before the war.19

WASHINGTON’S UNDERSTANDING OF THE “SACRED”

Since Washington was calling on his army to support the “sacred cause,” it is important to understand what he meant by the word “sacred.” He used the word fifty two times in his writings. There were two primary senses of the word in Washington’s use. The first use implied that something was dedicated or set aside exclusively for a single purpose or person. Second, when something was sacred, it meant that it was holy or set apart as a duty to God, and thus the object was worthy of reverence or the utmost respect.

Examples of the first use, where something was dedicated or set aside exclusively for a single purpose or person, includes the time given by an employee to an employer,20 money to be saved,21 boats to be used only for the military.22 Other examples from the military include the loyalty of a soldier that prohibits desertion,23 the flag of truce,24 the honor of a promotion in rank,25 the administration of justice belonging only to the civil magistrate and not the military,26 the distribution of food,27 maintaining the secrecy of passwords,28 the boundary line with the enemy,29 and the soldier’s arms.30 Washington’s papers that he possessed31 and those that were in the government archives32 were also sacred in this sense.

There are also several examples of the second use, where something is holy or set apart as a duty to God, and thus the object or activity is worthy of reverence or the utmost respect. In the diplomatic arena, this included the safety of an ambassador33 or the King.34 In military life, this included the discipline and character of an officer,35 the honor of the officer.36 The life and protection of the prisoner of war was a “faith held sacred by all civilized nations.”37 The government had sacred compacts and treaties,38 and citizens had sacred privileges.39 The president’s use of the powers of the Constitution was a sacred duty.40 The nation and the citizens possessed sacred ties,41 and sacred engagements.42 Honor and veracity were sacred enough to “extort” the truth even from a devious person.43 The nation had a duty to keep a sacred regard for public justice44 and have a sacred regard for the property of each individual.45 When war was pending, everything dear and sacred was at risk.46 In the more spiritual sense, there were books ordered for children that contained sacred classics,47 the private and sacred duties of the office of the chaplain,48 and the sacred duties due from everyone to the Lord of Hosts.49

It is clear that when Washington spoke of the “sacred cause,” he was using the phrase in the second sense, of something that was holy due its relationship with God. In a letter written to John Gabriel Tegelaar, he underscored that heaven’s favor and protection were deeply concerned with the survival of liberty.

May Heaven, whose propitious smiles have hitherto watched over the freedom of your republic still Guard her Liberties with the most sacred protection. And while I thus regard the welfare of your Country at large, permit me to assure you, that I shall feel a very particular desire that Providence may ever smile on your private happiness and domestic pleasures.50

And ultimately, Washington even believed that the sphere of the sacred extended to the realm of politics. He claimed that even when freemen disagreed over political issues, this was not a fault, since “they are all actuated by an equally laudable and sacred regard for the liberties of their Country.”51

If Heaven guarded liberty with “sacred protection” it surely was appropriate for citizen soldiers to pursue the “sacred cause” on earth. Such a precious gift was worthy of the greatest sacrifice, the kind the patriot army made at Valley Forge.

“…WITHOUT A HOUSE OR HUT TO COVER THEM….”52

As the army prepared to move out to Valley Forge, the general sought to put on the best face he could to address his soldiers’ desperate circumstances. On Dec. 17, 1777, Washington explained the army’s success, failures and hopes,

The Commander in Chief with the highest satisfaction expresses his thanks to the officers and soldiers for the fortitude and patience with which they have sustained the fatigues of the Campaign. Altho’ in some instances we unfortunately failed, yet upon the whole Heaven hath smiled on our Arms and crowned them with signal success; and we may upon the best grounds conclude, that by a spirited continuance of the measures necessary for our defence we shall finally obtain the end of our Warfare, Independence, Liberty and Peace. These are blessings worth contending for at every hazard. But we hazard nothing. The power of America alone, duly exerted, would have nothing to dread from the force of Britain. Yet we stand not wholly upon our ground. France yields us every aid we ask, and there are reasons to believe the period is not very distant, when she will take a more active part, by declaring war against the British Crown. Every motive therefore, irresistably urges us, nay commands us, to a firm and manly perseverance in our opposition to our cruel oppressors, to slight difficulties, endure hardships, and contemn every danger. The General ardently wishes it were now in his power, to conduct the troops into the best winter quarters. But where are these to be found?

There were reasons why the “best winter quarters” could not be found:

Should we retire to the interior parts of the State, we should find them crowded with virtuous citizens, who, sacrificing their all, have left Philadelphia, and fled thither for protection. To their distresses humanity forbids us to add. This is not all, we should leave a vast extent of fertile country to be despoiled and ravaged by the enemy, from which they would draw vast supplies, and where many of our firm friends would be exposed to all the miseries of the most insulting and wanton depredation. A train of evils might be enumerated, but these will suffice. These considerations make it indispensibly necessary for the army to take such a position, as will enable it most effectually to prevent distress and to give the most extensive security; and in that position we must make ourselves the best shelter in our power.

And what would be “the best shelter in our power”?

With activity and diligence Huts may be erected that will be warm and dry. In these the troops will be compact, more secure against surprises than if in a divided state and at hand to protect the country. These cogent reasons have determined the General to take post in the neighbourhood of this camp;

To make it all work, it would indeed be a matter of the “officers and soldiers” working “with one heart, and one mind.” They would have to “surmount every difficulty, with a fortitude and patience” and not forget “the sacred cause in which they are engaged.” Washington’s commitment to “share in the hardship, and partake of every inconvenience” was surely one of the elements of the next day’s “public Thanksgiving and Praise.”53

So on the next day, Thursday Dec. 18, 1777, plans for the huts were disseminated:

A field officer was to supervise a squad of twelve. The dimensions were to be 14’ × 16’ of logs, roof of split slabs, sides with clay, 18” thick on inside fireplace, door at street, side 6’ high.54

On Friday Dec. 19, 1777, the cold wind began to blow, piercing the soldiers’ threadbare garments as the snow began to fall. At 10 a.m., the American Army began its march to Valley Forge and upon arrival immediately began to lay out the grounds for their respective cantonments.

Saturday Dec. 20, 1777 saw the beginning of felling trees: “Soldiers cutting firewood are to save such parts of each tree as will do for building, reserving sixteen or eighteen feet of the trunk for logs to rear their Huts with.”55 Commands for straw governed a seventy mile region, requiring straw for beds, whereby each farmer had to thresh half his grain by February 1st, and the other half by March 1st for use by the soldiers, otherwise the army would seize all that the owner had.

On Sunday Dec. 21, 1777, a model of a hut was ready to be viewed at headquarters. While no enemy bullets flew at Valley Forge, there were many battles to be fought nevertheless. The immediate battle was over shelter, or the huts. The generals, who longed to head for their own homes for winter quarters, were not permitted to leave until all huts were done (General Orders of Dec. 27.) Washington, of course, never left for Mount Vernon until the war was over.

About the time of the battle of Germantown (October 1777), the northern American Army had won an astounding victory at Saratoga, under General Gates, who had just replaced Gen. Schuyler. But this victory to the north added pain for General Washington, not only in what became known as the Conway Cabal, which we will review later, but it also caused pain for the soldiers at Valley Forge. It was sarcastically observed that “Genl Burgoyne and his defeated Army are to be returned to Britain to sit out the War in the cold discomforts of the London Coffee Shops while we shall remain here in our warm, cozy Hutts living en prince off this generous land and enjoying our liberty.”56 Such was the ordeal of crafting the huts that, as human nature is so apt to do to cope with a difficult situation, the men wrote a poem about the pain and progress of the task:

Of ponderous logs:

Whose bulk disdains the winds or fogs

The side and ends are fitly raised

And by dove-tail each corner’s brac’d;

Athwart the roof, young sapling lie

Which fire and smoke has now made dry-

Next, straw wraps o’er the tender pole,

Next earth, then splints o’erlay the whole;

Altho’ it leaks when show’rs are o’er,

It did not leak two hours before.

Two chimneys plac’d at op’site angles

Keep smoke from causing oaths and wrangles.

Three windows, placed all in sight

Through oiled paper give us light;

One door, on wooden hinges hung,

Lets in the friends, or sickly throng.57

Christmas Day saw the soldiers slowly finishing their huts, still shivering in their tents, with hot smoke in their eyes when they tried to warm themselves by a fire, and with cold, piecing wind to greet them when they tired of the smoke.

By New Years Day, many soldiers were covered with good huts, as the soldiers worked like “a family of beavers.”58 But all huts still were not finally finished until February 7, 1778.

THE SOLDIERS’ SUFFERING AT VALLEY FORGE

Alongside the battle for shelter was the battle for clothing. The need for clothing—since uniforms were utterly impossible to find—was dramatized by the order that required the soldiers immediately to return their tents once their hut was completed, lest they cut them into clothing. Clothing was so scarce that Washington was forced against his will to seize it from the surrounding countryside: “His Excellency regrets the necessity of the measure of seizure of Cloathing. It was unavoidable. The alternative was to dissolve the Army.”59 The capture of a British Brig enabled the arrival of some officers clothes.60

The lack of clothing became so severe that “The unfortunate soldiers are in want of everything; they have neither coats, hats, shirts or shoes. Their feet and legs have frozen until they become black, and it is often necessary to amputate them.61 The Cloathing of those who have died in the Hospitals is to be appraised and delivered to those who have recovered and who stand in need thereof.62 “We still want for uniformity of Cloathing. We are not, like the Enemy, brilliantly and uniformly attired. Even soldiers of the same Regiment are turned out in various dress; but there is no excuse, as heretofore, for slovenly unsoldierly neglect.63 The insufficiency of clothing impacted everyone: Our sick are naked, our well naked, our unfortunate men in captivity naked!”64

There were not enough shoes. “As reported the 23rd inst., not less than 2898 men are unfit for duty by reason of their being barefoot and naked. We want for shoes, blankets, stockings…65 Troops are still wanting in shoes. While we have hides, gained from the slaughtering of beef, there are few shoemakers.”66 No soap or vinegar had been had by the troops since the Battle of Brandywine, which was three months past. “Soldiers have no kettles for boiling oil and soap.”67 The lack of salt gave a whole new meaning to the saying “with a grain of salt”—that’s the most that anyone had.68 Leather and wax were almost unavailable. “Writing paper is still in short supply.”69

Since there was no cattle, there was no meat.70 One soldier wrote, “Our present situation is the most melancholy that can be conceived. No meat, and our prospect is of absolute want.”71 This scarcity of food created soldiers’ chants and imprecations. One soldier wrote, “Provisions are scarce. A general cry thro’ the Camp this evening among the soldiers, ‘No meat! No meat!’ The distant vales echoed back the melancholy sound, ‘No meat! No meat!’” One of the soldierly cadences heard at Valley Forge was the antiphonal chorus of hungry soldiers chanting.

‘What have we for dinner boys?’

‘Nothing but Fire, Cake & Water, Sir!’”72

“Our situation for want of Cloathing, while mending, is yet distressing. Supplies are scanty; to give one part of the Army is to take from another. The Soldiers also say, ‘No bread, no soldier.’”73

The very essentials of the military were in short supply. “This army is short of powder….There is a deficiency of wagons.”74 The horses had starved due to lack of forage.75 Consequently, artillery was simply left because it could not be moved.76 “The carcasses of horses about the Camp, and the deplorable leanness of those which still crawl in existence, speak the want of forage equal to that of human food.77 Forage is wanting. Our horses starve, as do their masters. If help does not arrive, and forage does not appear, we shall not have one horse left.”78 Wood was becoming scarce due to the huts, and the need to heat them. “Now the trees have been burnt and firewood is being carted from a distance.”79

Medical issues were always a concern. Fortunately, it could be said that “Sanitation has not become a Camp problem.80 The Commander in chief urges caution with the drinking water, hitherto gathered from the little springs about the Camp.”81 Prevention of small pox was a critical concern. “More than two thousand men in Camp are to be inoculated for the Small Pox.”82 The lack of blankets and the insufficiency of straw contributed greatly to the mortality of the troops. “Unprovided with straw or materials to raise them from the cold earth, sickness and mortality have spread through the quarters of the Soldiers to an astonishing degree.”83 One of the tools to soften the pain and to lighten the burden was an occasionally generous ration of spirits. “This morning a gallon of spirits was drawn for each Officer’s mess, in all Brigades, against these raw and bitter days. Each man is to have a Gill of Rum.”84

But there were many other nagging problems that Washington’s army had to face, which meant they were ever before the commander in chief. “The discontent prevailing in the Army, from various causes, has become all too prevalent. Unless some measures can be adopted to render the situation of the Officers more comfortable than what it has been for some time past, it will increase.85 The whole Army in general has three months pay in arrears, not counting the months extra pay voted by the Congress.86 His Excellency expressed his superabundant sentiments of compassion for the miseries of the soldiery which are neither in his power to relieve or prevent. He is said to have written his doubt that unless some great and capital change suddenly take place in the Commissary Department, this Army must inevitably be reduced to one or the other of three things: starvation, dissolution or dispersal in order to obtain subsistence in the best manner it can.87 The soldiers are scarcely restrained from mutiny by the eloquence and management of our officers.88 Unless our future efforts to provide clothing are more effectual it will be next to impossible to keep our Army in the field.89 Even our Officers are tempted to steal fowls,—if they could be discovered, perhaps even a whole hog.90 Diverse soldiers, some on horseback, have been plundering the inhabitants; this probably arises at least from the rolls not being regularly call’d.91 To prevent the commission of those crimes, the Genl positively orders: 1st, That no Officer, under the degree of Field Office, or Officer commanding a Regiment, gives passes to non-commissioned Officers, or Soldiers, on any pretence whatever; 2nd, That no non-commissioned Officer, or Soldier, have with him Arms of any kind, unless he is on duty; 3rd, That every non-commissioned Officer or Soldier, caught without limits of the Camp, not having a pass, or with his Arms, shall be confin’d and punish’d. 4th, That the rolls of each Company be called frequently, and that every evening, at different times, between the hours of eight and ten o’clock, all the men’s quarters be visited…”92 Extortion in the name of Washington even began to occur: “…making use of his Excellency’s name to extort from the inhabitants by way of sale (or gift) any necessaries they want for themselves.”93

Problems with officers began to surface. Resignations, often prompted by complaints from home, began to occur. “Patriotism is not enough to carry men through a long war which makes demands on the families and men.94 Yesterday upwards of fifty Officers of Genl Greene’s Division resign’d their Commissions. Six or seven in the Connecticut Regiments did so today. This is occaision’d by Officers families being so much neglected at home…95 One of the complicated causes of complaints in this Army is the lavish distribution of rank.96 Major Genl John Sullivan was today refused leave of absence. Strenuous exertions of all the Officers are wanted to keep this Army together. Personal disputes should be settled amicably and they should not be brought to Court Martial or to the Genl as arbiter and referee.”97

Problems from the non-military people also appeared. “Sutlers have been selling spirituous liquors near the several pickets and out-lines of the Camp, which practice is to be stopp’d.98 Our money daily grows more worthless, and prices have become so excessive as to cause infinite difficulties. This proceeds more from currency depreciation and from general avarice than from real scarcity of many essential articles.”99 Prostitutes disguised as nurses100 and incidents of venereal disease101 prompted various attempts to correct the problem. “Pernicious consequences have arisen from suffering [permitting] Persons (women in particular) to pass and repass from Philada to Camp under pretence of coming out to visit Friends in the Army, but really with an intent of luring the soldiers and enticing them to desert.”102 But the arrival of the women could also mean that needed supplies were available. “Ten teams of oxen, fit for slaughtering, came into Camp, driven by loyal Philadelphian women. They also brought 2000 shirts, smuggled from the City, sewn under the eyes of the enemy.”103

POLITICAL INTRIGUES AT VALLEY FORGE

And on top of all of the enormity of the human struggle for life itself, there were the political intrigues of those who desired to remove Washington from power. The blame game was in full force at Valley Forge. “The want of Provisions in this Army stems in part from the defect in the system, but more from the indolence, disaffection & arrogance of the Commissaries.104 Some are disposed to ask why cannot Genl Washington grasp Genl Howe in the same fashion that Genl Gates seized Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne.105 Rumors circulate that Genl Conway wrote to Genl Gates with these words: ‘Heaven has been determined to save your Country, or a weak General and bad counselors would have ruined it.’ It is said that the Commander in Chief himself copied these words into a paper and introduced them with “Sir” and concluded with “I am your humble servant” and sent it to Genl Conway.106 Genl Lee [who had been captured by the Britishin New Jersey the previous year] will be formally exchanged tomorrow…Genl Gates continues his machinations.107

“Rumors late today that Congress has appointed the Marquis de la Fayette, Genl Conway and Brigadier Genl Stark to conduct an eruption into Canada. This comes from the Board of War, of which Genl Gates is the President, and was made without the knowledge of his Excellency. Rumors also come that Genl Lee is to placed at the head of this Army. The calm of his Excellency in face of these efforts to detach valiant Officers from this Army or to replace them, move him not. He says that as soon as the public grows dissatisfied with his services in an office he did not solicit he will quit the helm with much satisfaction and retire to a private station with as much content as ever the wearied pilgrim felt upon his safe arrival in the Holy Land.”108

Even though the enemy armies were in winter quarters, the hostilities never completely ended. “News today that Dr. Franklin was assassinated by a person who had concealed himself in his lodging room. The good Doctor was not wounded so as to be mortal, although this was thought to be so by the perpetrator.109...The Senecas and Cayugas can no longer be regarded as friends.110 They are endeavouring to ensnare the people by specious allurements of peace.111 The Tory paper…presents a scandalous forgery. Under the guise of a genuine Act of Congress it puts forth a statement that all men drafted to serve in the Continental Army are to be forced to serve for the whole war. The Enemy seeks thereby to encourage desertion.”112

The pacifist Quakers refused to take an oath or affirmation of allegiance to the American cause.113 Loyalists or Tories sought to hamper the American cause.114 Punishments of civilians occurred giving instances of whippings, confiscation of personal property and real estate. Active Loyalists even faced military judges in court martial with severe sentences that could result in “hard labour” or even execution.115

Ultimately, the battles at Valley Forge were fought in big and small ways. Sometimes the humor of Washington helped.116 But the biggest help was in the hope for the assistance of France and her allies due to the loyalty of Lafayette: “…the accounts from France are that the French, Spanish, Prussian and Polish Courts all have declared for the Independency of America by acknowledging them, and that a Treaty of Commerce was concluded by Dr. Franklin and the French Court for thirty years.”117 Eventually British support for the war would have to end given the debt they were accumulating.118 Oaths of allegiance were signed forcing out Loyalists.119 Morals were enforced, “But for the virtuous few of the Army, we are persuaded that this Country must long before this have been destroyed. It is saved for our sakes, and its Salvation ought to cause Repentance in us for all our sins, if evil and Misery are the consequences of Iniquity.”120

Military discipline was dramatically increased through the arrival of Baron Von Steuben. “The impression which our Camp has made upon the Baron is another matter. Our arms are in horrible condition, covered with rust…A great many of the men have boxes instead of pouches,…His description of our dress is not easily repeated…121 Baron De Steuben…drills them himself twice a day, seeking to remove the English prejudice which some Officers entertain, namely that to drill a recruit is a sergeant’s duty and beneath the station of an officer.122 The old system of manoeuvres is today suspended, as uniformity of disciplinary exercises is being established under the new Inspector Genl.123 Daily this Army looks more like a military force and less like an armed horde. We parade clean, dressed in proper regimentals, with proper arms and accoutrements.”124

And through it all, Washington sought to never lose his grace. When one hundred medical books intended for a British physician were captured, the record states “His Excellency magnanimously allows these volumes to be return’d to the Doctor to show that we do not war against the sciences.125 I have not indulged myself in invective against the present rulers of Great Britain, nor will I even now avail myself of so fruitful a theme.”126 The presence of Mrs. Washington made a difference.127 The ministry support of the women of Bethlehem also helped.128 And there even was an occasional dance, or play to provide some entertainment.129

And finally the day came when “the Genl addressed his warmest thanks to the virtuous Officers and Soldiery of this Army for that persevering Fidelity and Zeal manifest in all their conduct.”130

Washington expressed his sense of gratitude at the end of this long winter when he wrote to fellow Virginian Landon Carter from Valley Forge on May 30, 1778,

My friends therefore may believe me sincere in my professions of attachment to them, whilst Providence has a joint claim to my humble and grateful thanks, for its protection and direction of me, through the many difficult and intricate scenes, which this contest hath produced; and for the constant interposition in our behalf, when the clouds were heaviest and seemed ready to burst upon us.

To paint the distresses and perilous situation of this army in the course of last winter, for want of cloaths, provisions, and almost every other necessary, essential to the well-being, (I may say existence,) of an army, would require more time and an abler pen than mine; nor, since our prospects have so miraculously brightened, shall I attempt it, or even bear it in remembrance, further than as a memento of what is due to the great Author of all the care and good, that have been extended in relieving us in difficulties and distress.131

As we conclude this chapter, we turn our attention to the question of whether Washington really prayed at Valley Forge. Given all of the above, it seems to us that a more legitimate question to ask is how he could have survived Valley Forge without prayer!

DID WASHINGTON PRAY AT VALLEY FORGE?

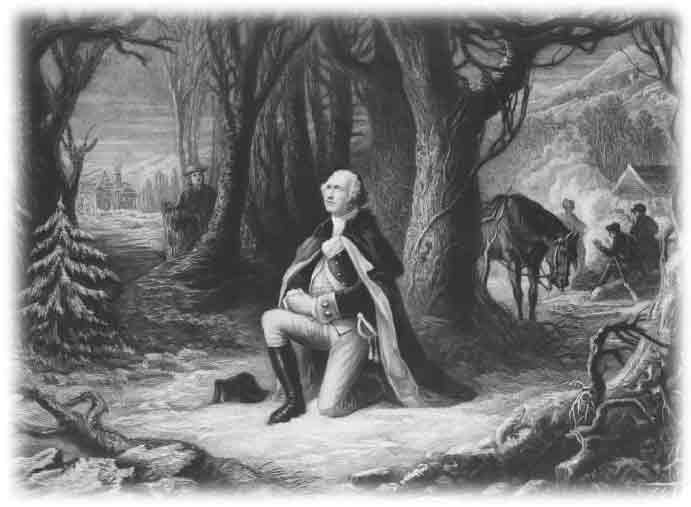

When Washington was at Valley Forge, during the brutal winter of 1777-1778, it was alleged that he was overheard in prayer by a Tory-sympathizer, a Quaker named Isaac Potts. This man supposedly came across General Washington in prayer in the woods and then came home and declared to his wife, “Our cause is lost.” He feared that the rebels would win the war, because he heard their leader in earnest audible prayer and had become convinced there was no way that God would not honor that prayer.

Boller discounts this story as part of unreliable oral tradition.132 Earlier generations of Americans, however, accepted it as historically reliable. Consider, for example, the 1903 Episcopal Washington Memorial Chapel in Valley Forge built to commemorate the story; a 1928 two-cent U.S. postage stamp of Washington in prayer at Valley Forge; a 1955 stained-glass window of the scene in the Prayer Room in the U.S. Capitol building; and a bronze rendition of Washington’s “Gethsemane” in the Sub-Treasury Building in New York City.

Why does Boller think this story is apocryphal? In part, because of differences that exist in the traditional story. One version has the man’s name as Isaac Potts. Other versions have a different name for the Quaker as well as his wife. Moreover, the Potts family that owned the house, still known as Washington’s Headquarters, have no records that would indicate that Potts made a trip that winter to Valley Forge, where he would have had the occasion to have stumbled on Washington kneeling in the snow in private prayer.

As Boller presents it, there is no hard evidence that the story ever occurred. All we have is the mythic legend preserved in the unsubstantiated story told by the Reverend Mason Weems. Yet, Boller admits that there were others who gave evidence to the account.133 Rather than engage them, he simply dismisses them with his uncritical remark, “…scores of witnesses attesting to the event (many years later) have been dug up by champions of the story; and many details have been added by later writers to Weems’s original account. . . .The Valley Forge story is, of course, utterly without foundation in fact.”134

What is the extent of Boller’s proof? Only the words just cited. That is all he has to say about the subject that built a million dollar church, created one of the best selling postage stamps in history, is reflected on two U.S. government buildings, and prompted President Ronald Reagan to say, “The most sublime picture in American history is of George Washington on his knees in the snow at Valley Forge. That image personifies a people who know that it is not enough to depend on our own courage and goodness; we must also seek help from God, our Father and Preserver.”135 Doubt and criticism are good tools for the historian, but when they allow a historian to fail to do his work and to reach a scientifically justifiable conclusion, they are no longer tools, but expressions of a hostile, prejudicial philosophy.

Our purpose here is not to do the extensive research that would be required to demonstrate what elements of truth are extant in the oral history and accounts that have preserved the tradition of Washington’s prayer at Valley Forge. Moreover, our argument for Washington’s Christianity is not dependent upon the validity of this anecdote in any way. The evidence we have employed is built directly on Washington’s own words. However, we believe that a respectable, historical discussion of this matter at least requires an awareness of the information that Boller simply sweeps under the rug of his skepticism.

All told, there are five different individuals who gave an account of Washington praying at Valley Forge. They are: Reverend Mason L. Weems,136 Washington historian Benson J. Lossing,137 Reverend Devault Beaver,138 Dr. N. R. Snowden, who claimed to have heard it directly from Isaac Potts himself,139 and General Henry Knox.140

Could this story be true? By the strictest, critical standards of historical investigation, we cannot establish its validity. We have no letter from Washington or Isaac Potts declaring that this is what happened. There is no contemporary newspaper account that relates these facts. By the standards of oral history, however, it appears to have a legitimate claim for being considered as a possible historical event. Oral history recognizes that rigorous, critical, historical proof is not the only way history is preserved. It is one thing to say that an oral report of an incident cannot be proven by an eyewitness or a participant’s written report; it’s another thing to say it did not happen. The multiplicity of testimony and the claim of a remembered interview recorded for posterity suggest that something may well have happened in the snowy woods of Valley Forge.

Our purpose here is not to prove the story, but to show that Boller’s cavalier approach to the facts of oral history also reflect his lack of consideration of the written record of Washington and his contemporaries. So even though Boller asserts, “The Valley Forge story is, of course, utterly without foundation in fact,” we wish to determine what are the critical and historical facts that we do know about George Washington as a man of prayer? And what we know argues decisively that Washington prayed at Valley Forge, whether Isaac Potts saw him or not.

First, there is indisputable, written evidence from George Washington that he fervently prayed for himself and for the success of his army only months before the painful winter of Valley Forge. In a letter to Landon Carter that Washington wrote from Morristown on April 15, 1777,

Your friendly and affectionate wishes for my health and success has a claim to my most grateful acknowledgements. That the God of Armies may Incline the Hearts of my American Brethren to support, and bestow sufficient abilities on me to bring the present contest to a speedy and happy conclusion, thereby enabling me to sink into sweet retirement, and the full enjoyment of that Peace and happiness which will accompany a domestick Life, is the first wish, and most fervent prayer of my Soul.141

Clearly, Washington wanted the war to end and had already been longing to go home. If Washington fervently prayed for this before the sufferings of Valley Forge, it seems certain that he prayed at Valley Forge, when all he had to count on for victory was the bare hope that God might answer his prayers. To show that this was not a misstatement on Washington’s part, it is significant that virtually the same words were used by Washington just three days earlier in a letter to Edmund Pendleton,

Your friendly, and affectionate wishes for my health and success, has a claim to my thankful acknowledgements; and, that the God of Armies may enable me to bring the present contest to a speedy and happy conclusion, thereby gratifying me in a retirement to the calm and sweet enjoyment of domestick happiness, is the fervent prayer, and most ardent wish of my Soul.142

Second, there are dire circumstances of Valley Forge found in Washington’s description already quoted of the sufferings of his men that winter of defeat and despair. The capitol city of Philadelphia lay in the conquerors’ hands, and Congress had been forced to flee to Lancaster and York. Clearly, this was an occasion for the deepest groanings of prayer for a man of faith. Given that Washington’s life and writings show he practiced daily prayer, it is no stretch of historical credibility to affirm that Washington was praying at Valley Forge. The point here is that we don’t need the alleged Quaker to prove that General Washington was given to “fervent prayer.” His own pen tells us that such was the case.

Also, if we are looking for testimonies of Washington’s prayer life by those who observed it, why pursue Isaac Potts, when there are so many other historical examples that are readily at hand? There are other traditional accounts of Washington praying at Valley Forge beyond those that we’ve mentioned so far, such as his prayer for a dying soldier at Valley Forge.143 But we will not appeal to this account, even if it may have an element of authenticity. After all, we have already seen that there are over one hundred written prayers in Washington’s writings, which we have already addressed in the chapter on Washington and prayer. Beyond this, there are the historical affirmations that Washington was a man of prayer.

…it was Washington’s custom to have prayers in the camp while he was at Fort Necessity.144

He regularly attends divine service in his tent every morning and evening, and seems very fervent in his prayers.145

Throughout the war, as it was understood in his military family, he gave a part of every day to private prayer and devotion.146

… the Reverend William Emerson, who was a minister at Concord at the time of the battle, and now a chaplain in the army, writes to a friend: There is great overturning in the camp as to order and regularity. New lords, new laws. The Generals Washington and Lee are upon the lines every day. New orders from his Excellency are read to the respective regiments every morning after prayers.147

Some short time before the death of General Porterfield, I made him a visit and spent a night at his house. He related many interesting facts that had occurred within his own observation in the war of the Revolution, particularly in the Jersey campaign and the encampment of the army at Valley Forge. He said that his official duty (being brigade-inspector) frequently brought him in contact with General Washington. Upon one occasion, some emergency (which he mentioned) induced him to dispense with the usual formality, and he went directly to General Washington’s apartment, where he found him on his knees, engaged in his morning devotions. He said that he mentioned the circumstance to General Hamilton, who replied that such was his constant habit.148

…when …Elizabeth Schuyler was a young girl, before her marriage to Alexander Hamilton, she was with her father, General Philip Schuyler, one of Washington’s aides, at Valley Forge, and saw the terrible sufferings of our men, and heard at that time Washington’s fervent prayer that all might be well.149

Third, Washington prayed in the winter following Valley Forge. Although Washington’s soldiers faced great sacrifice, in this instance provision came to meet the needs of the troops. And this prompted his “ardent” prayer. He wrote to Eldridge Gerry, from Morris Town on January 29, 1780,

With respect to provision; the situation of the army is comfortable at present on this head and I ardently pray that it may never be again as it has been of late. We were reduced to a most painful and delicate extremity; such as rendered the keeping of the Troops together a point of great doubt.150

Washington had not forgotten how difficult it was when the army’s needs had not been met. He prayed that the painful circumstances would not be repeated, though the need had been met. If he prayed in a time of provision, would it have been likely that he would not have prayed in the midst of great need in the first instance? Would we not expect him to have prayed, especially since the record of his consistency in prayer was written repeatedly in undeniable, historical records?

Finally, we can verify one time when Washington prayed at Valley Forge from his own writings. This is found in his General Orders for April 12, 1778, that called for prayer following the Congressional Proclamation.

The Honorable Congress having thought proper to recommend to The United States of America to set apart Wednesday the 22nd. instant to be observed as a day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer, that at one time and with one voice the righteous dispensations of Providence may be acknowledged and His Goodness and Mercy toward us and our Arms supplicated and implored; The General directs that this day also shall be religiously observed in the Army, that no work be done thereon and that the Chaplains prepare discourses suitable to the Occasion.151

CONCLUSION

The last time Washington wrote the phrase “sacred cause” was as his men were heading for Valley Forge. It was as if the sacred cause had been internalized, or become a reality. The next dramatic moment when he would return to this powerful image would be in his First Inaugural Address where his “sacred cause” had become the “sacred fire of liberty.” Not only had freedom’s holy light not gone out, but it was burning brightly ready to ignite other hearts and other nations.

So could a Quaker have found Washington on his knees in secret prayer, in the snow, at Valley Forge? If we could have asked the opinion of the colonial Lutheran minister Reverend Muhlenberg, he would have not have found the claim unbelievable about the one who was “graciously held” in God’s “hand as a chosen vessel.”

Thus, the question can no longer really be whether Washington prayed at Valley Forge and was seen by a pacifist Quaker who converted to the American cause. Those events may have happened, but they cannot ultimately be proven. The question instead must be whether Washington prayed at Valley Forge. The only possible answer consistent with all that we know is “yes.”

But perhaps the more relevant question is why scholars are insistent on telling the truncated secular version of Washington’s encampment at Valley Forge? Why would they tell the story of Washington’s great triumph in the battle over doubt and despair without reference to his “sacred cause?” without reference to Washington’s faith in Jehovah? without reference to his call for his men to be Christians? Were not these the things that produced “the sacred fire of liberty” that kept his men united in spite of their extreme exposure to the frigid winter winds of Valley Forge? Why then would scholars censure the sermon of Chaplain Israel Evans made at Valley Forge when it had the full approval of Washington? We can no longer tell the story of the Valley Forge encampment without looking on “his excellency General Washington” as Israel Evans admonished,

... Look on him, and catch the genuine patriot fire of liberty and independence. Look on him, and learn to forget your own ease and comfort; like him resign the charms of domestic life, when the genius of America bids you grow great in her service, and liberty calls you to protect her. Look on your worthy general, and claim the happiness and honour of saying, he is ours. Like him love virtue, and like him, reverence the name of the great Jehovah. Be mindful of that public declaration which he has made, “That we cannot reasonably expect the blessing of God upon our arms, if we continue to prophane his holy name. Learn of him to endure watching, cold and hardships, for you have just heard that he assures you, he is ready and willing to endure whatever inconveniencies and hardships may attend this winter. Are any of you startled at the prospect of hard winter quarters? Think of liberty and Washington, and your hardships will be forgotten and banished.152

Perhaps the reason the secularists have forgotten the inseparable connection between Washington’s “sacred cause,” his “patriot fire of liberty,” and his “all wise and powerful Being” is because they have been so intent on finding a Deist Washington. As a result of their quest, they clearly have not shared “the first wish of his heart.” This wish was “to aid pious endeavours to inculcate a due sense of the dependance we ought to place in that all wise and powerful Being on whom alone our success depends.” General Washington was here referring to Jehovah, the God of the burning bush, and the inexhaustible energy of the “sacred fire of liberty.”