Stephen Abram

Chapter 3, “Librarianship: A Continuously Evolving Profession,” highlights the many trends that impact information professionals today and emphasizes how information professionals must continuously adapt to change. As head of Lighthouse Consulting and with his background in leadership in special library organizations, Stephen Abram provides needed insight for information organizations as they adapt and evolve in response to the evolutionary trends of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Some changes, notes Abram, are easy to see, such as new technology, while other changes, such as social behaviors that impact information organizations, are harder to identify. A key challenge for information organizations today is that they serve a hybrid world where some people prefer the old ways and others race forward to new modes of behavior. Cooperation on a sustainable and scalable basis is another significant challenge emphasized by Abram.

Key professional competencies addressed by Abram include leadership, strategic planning, an understanding of the economic context, and the ability to embrace change. Abram not only concludes chapter 3 with an emphasis on the importance of lifelong learning but also provides the reader a wealth of essential resources, such as lists of LIS reports, statistical datasets for information organizations, and recommended readings. These resources are further extended in the online supplement.

* * *

Throughout history, libraries and other types of information organizations have continuously adapted to changing environments and technology—with collections evolving from scrolls to the codex, card catalogs to online catalogs, print indexes to full-text databases, and in-person reference support to virtual reference services. Add in huge interventions starting from the fringes (e.g., the internet, e-mail, social media, etc.), and you see adaptation and evolution on a very large international scale. As societies have grappled with the pressing issues of their time and place, information organizations have wrestled with those same challenges (e.g., should information organizations be places where racial segregation is practiced?). Information organizations today continue to adapt and evolve, not just as reflections of the changes in society but also as thought leaders in their communities and as places of research that drive those changes (see also chapter 2: “Libraries, Communities, and Information: Two Centuries of Experience”).

This chapter explores the evolutionary trends of information organizations and information professionals in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. After completing this chapter, the reader should have an understanding of how information professionals must continuously adapt to change—not only for survival but also to thrive as agents of change.

A “change agent” is anyone who helps an organization or community transform by improving business and learning processes and personal and professional interactions (see also chapter 20: “Change Management”). These changes expand beyond e-books and the web by representing a fundamental challenge to the underpinnings of the profession’s values and the basic business models and missions of information organizations.

While technology gets most of the attention when change is discussed, the main thrust of change in information communities is human behavior. Some changes are easy to see, such as new technology, while other changes, such as social behaviors that impact information organizations (e.g., web-savvy users who demand virtual access to resources), are harder to identify. Despite its complexity, change is important to the history of information organizations. As a wise person once said, dinosaurs did not die out because of climate change; they died out because they failed to adapt. A key challenge for information organizations is that they serve a hybrid world where some people prefer the old ways and others race forward to new modes of behavior. Libraries must have a foothold in all camps to succeed.

CHANGE AND ADAPTATION IN THE INFORMATION PROFESSION

The history of the information profession is characterized by the need to adapt to change. People who act as catalysts for change have five basic philosophies or skills: they have a clear vision, are patient yet persistent, ask tough questions, are knowledgeable and lead by example, and maintain strong relationships built on trust.1 Historically, change was easier to adapt to, since changes took place over a longer period, and society and technology did not transform as rapidly as they do today. For example, it took centuries for the book format, global literacy, and universal education to spread widely, and, indeed, more modern technologies such as television and the telephone took many decades to widely penetrate the market. Such is not the case today, with technological changes moving across the globe in mere years. And with each technological change, human behavior also changes—changes that can no longer be defined by generation.

“Information professionals used to have time to respond and evolve, but the information revolution is just that—a revolution where things change rapidly. This ever-evolving environment requires a stronger set of competencies and leadership skills to steer the institution and its staff. „

Information professionals used to have time to respond and evolve, but the information revolution is just that—a revolution where things change rapidly. This ever-evolving environment requires a stronger set of competencies and leadership skills to steer the institution and its staff. Bureaucratic processes, which have traditionally comprised best practices in the public sector to protect the public purse, have become the enemy of nimbleness, which is needed in this environment. Especially for those who work in the public sector, there is a need for cultural change within the information organization. Proactivity instead of reactivity is one place to start. Information professionals need to do more than just see the changes currently happening; they need to get out in front of them—forecasting what is to come and proactively moving ahead to adapt to these changes.

There are dynamic tensions in the information field between conservative approaches to change and a more aggressive approach. Balancing these tensions and having the ability to identify trends and adapt to change are rare and important attributes of leaders in the information profession (see also chapter 37: “Leadership Skills for Today’s Global Information Landscape”). Some of the critical and difficult questions that the profession’s leaders struggle with every day include:

• What trends are “real,” and which ones are fads?

• Which trends are relevant to information organizations and worth an investment of time and effort to explore?

• Which trends are more important than others, and how do information professionals set priorities?

• What strategies can be used to bring staff, management, and communities along the curve of innovation, especially when the future opportunities and threats are clear to some but not to others?

There are definite benefits to spotting trends early. As an example, those who saw the internet, mobile devices, or smartphones as opportunities early in their transformation were better prepared to respond to these trends. Similarly, the profession’s innovators who jumped in with both feet to the Second Life 3-D immersive environment or QR codes gained experience that helped them evaluate future gamification, geo-location, near-field communication (such as iBeacons for mobile phones), and 3-D learning environments. Today, for example, information professionals experiment with drones, Apple iBeacons,2 and gamification with augmented and virtual reality, visualization tools, and linked data. Each will follow its own arc; some will reach mass adoption, and some will be evolutionary distractions. Learning happens every step of the way, and the learning curve is usually too steep to start late.

The right strategy is to explore opportunities and take risks in a careful and controlled way through betas, pilots, experiments, and trials. One strategy is to work in partnership with vendors as they research and experiment. Another is to work through associations, collaboratives, and consortia to share the expense, effort, and risk with others. Information professionals can also pilot new ideas with small groups of targeted end users to get feedback on their ideas and innovations.

THE VALUE OF THE INFORMATION PROFESSIONAL

Two things help professionals choose to evolve: a focus on the core values that never change, and knowledge regarding the distinct value they deliver better than anyone else in their community.

Information professionals are fundamentally about transforming lives. Information professionals who focus on information transactions, such as circulating books and DVDs or answering in-person reference questions, are missing the opportunity to communicate the true contributions they provide to their communities. Information organizations should not define themselves solely based on their collections and services (e.g., web search engines, e-books, podcasts). Instead, the focus should be on the impact of information professionals on people’s lives. As such, the role of information professionals continues to evolve beyond the physical setting to one where they are positioned as drivers of change. Information professionals must continue to serve as advocates on important issues, such as the right to read, academic and intellectual freedom, digital rights and copyright, and censorship (see also chapter 28: “Advocacy”).

“The role of information professionals continues to evolve beyond the physical setting to one where they are positioned as drivers of change. Information professionals must continue to serve as advocates on important issues, such as the right to read, academic and intellectual freedom, digital rights and copyright, and censorship. „

DRIVERS OF EVOLUTION

To what extent are information organizations aligned with user expectations, trends, and best practices? What must change to better position the information organization to face the challenges of the next ten to fifteen years and to ensure that the organization continues to be a relevant and meaningful community institution? These are critical questions to consider in ensuring that the information profession continues to evolve and thrive in the future (see also chapter 4: “Diverse Information Needs”).

One way to critically assess the organization’s capacity to anticipate and respond to a changing world is through strategic planning (see also chapter 19: “Strategic Planning”). Strategic planning is about abandoning outdated practices and embracing change. A strategic plan needs to chart a bold new direction for the organization that is consistent with the changing needs of users (and, perhaps more importantly, nonusers) so it will be a useful tool for predicting and managing future service delivery.

A key component for planning for change is to review the economic context. There are macroeconomic trends that are big, global trends that affect information organizations, such as recessions, depressions, and stock market changes. There are microeconomic trends that are local, municipal, state, or national trends that affect information organizations closer to home, such as natural disasters, political changes in state and local government, and immigration/demographic changes. There are also economic changes on the organizational level, such as changes in executive leadership, mergers and acquisitions, or fiscal revenue or sales success. Regardless of their origin, each trend requires a thoughtful response. As is discussed later in the chapter, information professionals need to position the information organization effectively as having an important impact on the parent organization’s decision making and not just be viewed as a cost center. Forecasting the economic context of the organization or community will deliver insights regarding the strategic direction that the organization’s decision makers need to consider.

“A strategic plan needs to chart a bold new direction for the organization that is consistent with the changing needs of users (and, perhaps more importantly, nonusers) so it will be a useful tool for predicting and managing future service delivery. „

Looking at the big picture, major changes to the information profession are already taking place. The functions and roles of information organizations are changing with the surge of information and technologies. These organizations are no longer simply “warehouses” for print material that is borrowed by residents for off-site use—if they ever really were. Increasingly, these organizations are information, program, and cultural centers supporting a wide range of community, business, or research activities and objectives. The way people are using information is also shifting, with physical access plateauing and remote access increasing. The function and design of information organizations are evolving in response to these changing roles and demographic shifts, emerging technologies, and increasing consumer expectations for what they want out of the organization’s service portfolio.3

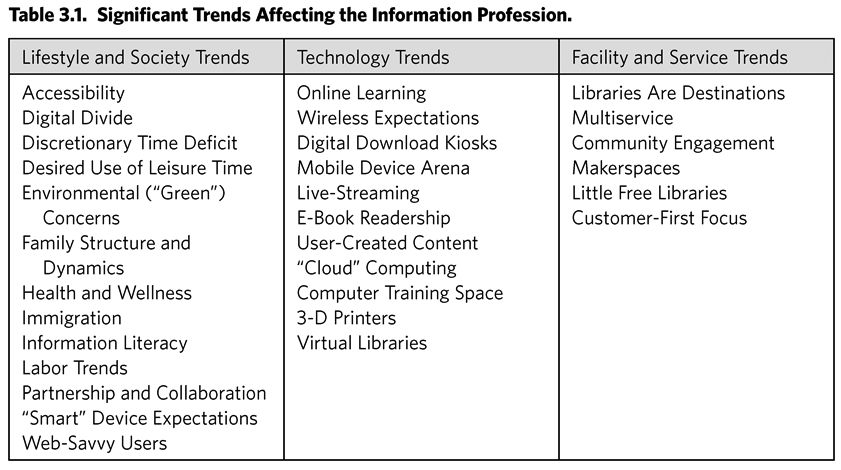

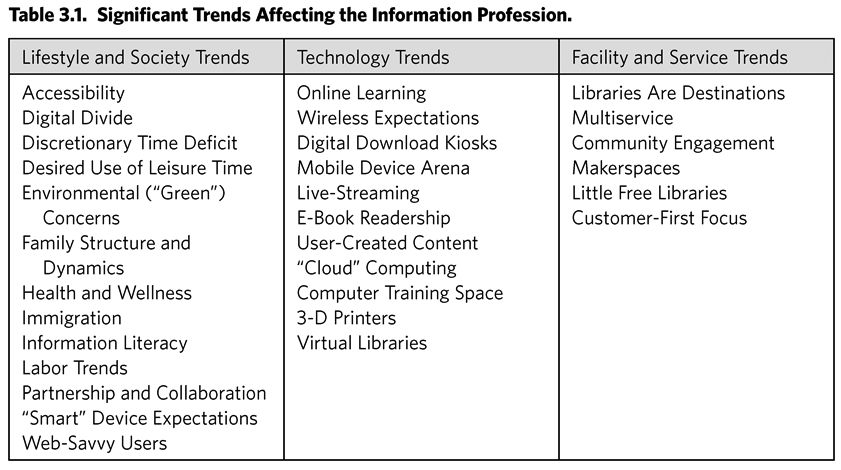

Looking specifically at the significant trends affecting information professionals and organizations today, these changes are grouped into three areas as demonstrated in table 3.1.

Lifestyle and societal trends have significant implications for ways that information organizations need to evolve. For example, changes in family structures and dynamics (the rise of nontraditional family structures, the declining predominance of two-working-parent households, a rise in commuter lifestyles, increased urbanization, and shared households) have implications for information organizations in terms of hours of operation, asynchronous (virtual) programming, and the delivery of programs and services both within and outside their physical location.4 (See appendix 3.1: “Lifestyle and Societal Trends” for a more comprehensive explanation of these trends.)

Technology trends are constantly and rapidly developing, making them hard to predict. One key trend, the growth of online learning and open education resources (OER), has created issues that, to date, have largely affected academic libraries (see also chapter 7: “Learning and Research Institutions: Academic Libraries”). However, e-learning is starting to influence services in public libraries too. For example, in the United States, the Los Angeles Public Library (LAPL)5 system offers a fully accredited online high school with full credits, diplomas, and graduations. LAPL provides a wonderful resource that offers users access to e-learning programs for adults and high school students and makes a huge difference at the individual level of impact (see appendix 3.2: “Technology Trends” for a more comprehensive explanation of these trends).

Facility and service trends point to an information organization that is much more integrated into the affairs of the community. The makerspace movement (see also chapter 18: “Creation Culture and Makerspaces”) is a good example of trends in this category, with information organizations providing spaces for users to collaborate, learn hands-on skills, and create and produce something such as music, videos, jewelry, games, robotics, and electronics (see appendix 3.3: “Facility and Service Trends” for a more comprehensive explanation of these trends).

FORECAST: EMERGING TRENDS AND ISSUES

The future trends and issues mentioned above will require information professionals to remain forward thinking—both for their organizations as well as their professional development. How will information professionals evolve and adapt in the coming years?

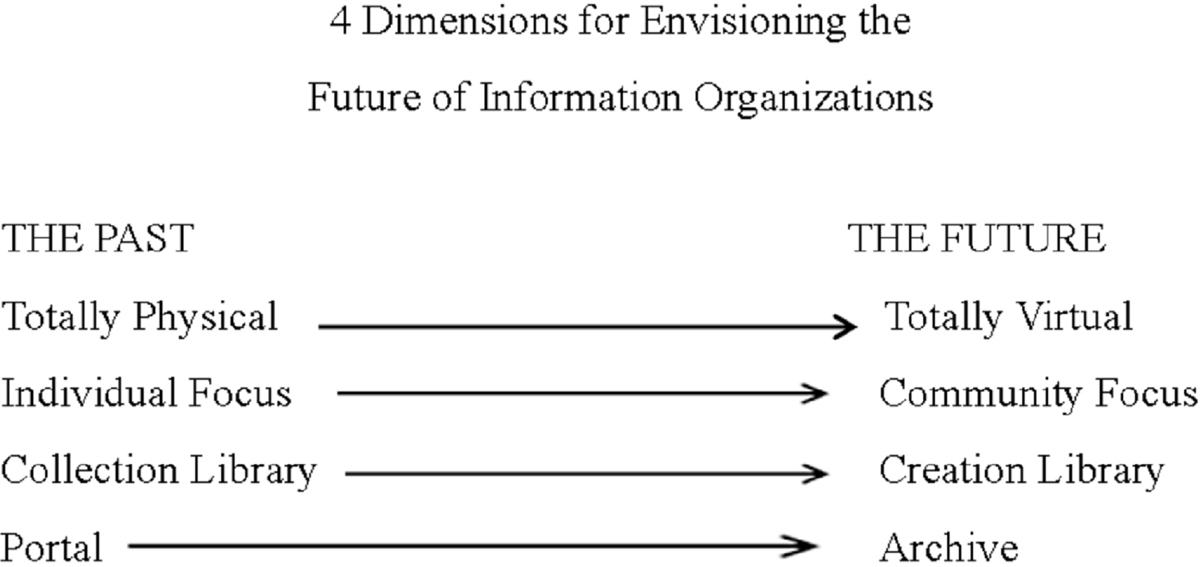

In his report, Confronting the Future, Roger Levien addresses the major issues facing information organizations and provides a framework for envisioning the future (see figure 3.1). Levien introduces four “dimensions,” each of which consists of a continuum of choices that lie between two extremes.6

While the framework was specifically designed for public libraries, these dimensions can also be applied to other information organizations (see also chapter 6: “Literacy and Media Centers: School Libraries,” chapter 7: “Learning and Research Institutions: Academic Libraries,” and chapter 9: “Working in Different Information Environments: Special Libraries and Information Centers”). To meet the challenges they will face in the future, information organizations must make strategic choices concerning their place on each of the four dimensions identified by Levien. These four dimensions are described below.

Figure 3.1 Four Dimensions for Envisioning the Future of Information Organizations. Adapted from Roger Levien, “Confronting the Future: Strategic Visions for the 21st Century Public Library,” American Library Association Policy Brief, no. 4 (2011).

Dimension 1: Physical to Virtual

This dimension relates to the form of the information organization as a facility and to the format of its collection. On one end of this spectrum is a purely physical organization; however, this sort of organization is no longer considered realistic. On the other end is the virtual organization—a space on the web that hosts all of the organization’s services and collections and is accessible to users through the organization’s web presence anywhere over the internet. On this spectrum, most modern libraries are somewhere in the middle, still offering a physical building and collection, while increasingly providing virtual features, such as e-books and online services.

Dimension 2: Individual Focus to Community Focus

This second dimension relates to the type of service provided by the information organization and the point of focus for its users. The extremes, in this case, are individual-focused organizations and community-focused organizations. Organizations that focus on the individual seek to accommodate each user independently with quiet study space, privacy, comfort, and minimal distractions. In this scenario, the primary relationship is between the information professional and the individual user. Those organizations that focus on the community look to provide space for community interaction and group work. These organizations, often identified as “community centers,” invest considerable resources in a broad range of services, events, and programs that engage the community. They also often contain archives of local records, artifacts, memoirs, and memorabilia.

Dimension 3: Collection to Creation

This third dimension relates to how information organizations interact with and engage their users. On one end of the spectrum is the collection-focused organization, where users come to enjoy and experience the materials in the organization’s collection. This organization is a repository of intellectual and recreational information available for the user to explore. The other extreme is an organization where, instead of simply exploring the works of others, users are encouraged to see the organization as a creative space where equipment and facilities are provided to produce their own creative products.

Dimension 4: Portal to Archive

This fourth dimension of Levien’s report relates to the ownership of the collection. In the portal model, the materials available to users are not the property of the information organization. Instead, the information organization acts as a facilitator between the user and resources that are available through other organizations. On the other end of the spectrum is an archive model, where the information organization’s role is to possess documentary materials in a range of genres and mediums. In the archive model, the information organization has an important role in assembling and disseminating local information (and not simply historical information). This information organization is a living community resource that tells the community’s story—past, present, and future.

“Planning and implementing successful strategies that span and engage the digitally literate and nonliterate, technology aware and technology phobic, and cover diverse kids, teens, and adults are big challenges. „

Today’s information leaders are not just managing organizations stacked with books and reference materials, but something far more complex and complicated. Leaders must now manage a hybrid organization with a market of users who display infinite levels of diversity (see also chapter 5: “Diversity, Equity of Access, and Social Justice”). Planning and implementing successful strategies that span and engage the digitally literate and nonliterate, technology aware and technology phobic, and cover diverse kids, teens, and adults are big challenges.

Discussion Questions

Using Levien’s typology, where is the library on these continuums today? In your view, where should the library be in ten to fifteen years? How can a strategic plan assist information professionals in repositioning themselves on these continuums?

SUSTAINABILITY OF TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY INFORMATION ORGANIZATIONS

Some challenges regarding the value and sustainability of information organizations remain—especially in terms of taking risks and influencing decision makers, building cooperative relationships, and ensuring adequate funding. While some information professionals can adapt and evolve to meet the challenges of a changing environment, too many information professionals still shy away from risk, avoid confrontation, and lack strong ties to decision makers. Information professionals must develop the leadership capabilities necessary to thrive in this dynamically changing environment, while encouraging staff to embrace change and fighting the need for too much control in an increasingly ambiguous future (see also chapter 37: “Leadership Skills for Today’s Global Information Landscape”). Information professionals also need to develop effective soft-management skills (e.g., vision, influence, presentation skills, professional networking, change and risk management strategies, strategic budgeting, and marketing) to improve their influence and positioning.

“Information professionals must develop the leadership capabilities necessary to thrive in this dynamically changing environment, while encouraging staff to embrace change and fighting the need for too much control in an increasingly ambiguous future. „

Another significant challenge is cooperation on a sustainable and scalable basis. Information organizations had a huge vision when the Online Computer Learning Center (OCLC) was created in the 1970s. This not-for-profit collaborative redefined the cataloging and metadata space and is a key part of such services as Amazon and Google Books. However, since then, no other entities have been created and continued on such a global scale to effectively address the challenges of scalability, content creation, systems, apps, websites, and more. For example, initiatives such HathiTrust,7 Digital Public Library of America,8 and Europeana9 show promise but still require maturing to achieve full utility. Consortia struggle with issues of scale. To get the best prices through cooperative buying, they must get bigger and more powerful as they bring information organizations to the table as buyers. The technological changes happening in the information field provide opportunities for consortia to become major infrastructure players for the information sector.

Sustainability of information organizations cannot be discussed without mentioning funding (see also chapter 21: “Managing Budgets”). Unfortunately, recent financial trends typically involve reduced funding for information organizations, while expecting the same level of services, or even expanded services. This situation puts information organizations in a difficult position. The solution to this problem is both complicated and complex. Some organizations and jurisdictions have been able to clearly articulate the case for adequate funding, and, as a result, they have thrived, while some have been forced to reduce services or close due to lack of funding. The long-term solution rests in better communication, advocacy, and relationships with decision makers, as well as efforts to drive productivity enhancements and cost efficiencies (see also chapter 27: “Communication, Marketing, and Outreach Strategies”). For example, initiatives, such as the Political Action Committee for libraries in the United States, have been very successful in public library levy votes, as has the Federation of Ontario Public Libraries Open Media Desk social media campaign. While libraries, for example, tend not to be businesses, they must behave in a businesslike fashion (using expected best practices) in today’s public funding environment.

Check This Out

Online Computer Learning Center (OCLC). Visit: http://www.oclc.org

Discussion Questions

What trends do you consider important that have not been touched on in this chapter or this book? Are they different for different types of libraries (special, academic, public, school)?

ESSENTIAL RESOURCES TO STAY AHEAD OF THE CURVE

So how can information professionals stay ahead of the curve and avoid fighting fires? How should information professionals learn about the future? It is simple really—read widely. Information professionals must engage in continuous environmental scanning to be successful and adaptive—and not just every five years as part of a strategic planning process. While it is important that information professionals read professional development content that comes from library and information science literature and sources, it is equally important that information professionals extend their learning by following publications in focused subject fields (such as user experience, copyright law, etc.) and experts in popular culture, technology, education, and other areas that are of interest. Print is rarely the right medium for exploring trends. Blogs, discussion boards, and conferences are where the real action takes place.

What resources, blogs, readings, strategies, and social media should be in the professional’s personal learning network (PLN)? While the real transformative trends tend to happen on the fringes, it is useful to read a variety of resources to gain insight regarding how innovators and early adopters are experimenting and pioneering with new methods, technologies, and ideas. Some examples of quality research organizations that cover the information profession are described below, and additional resources are covered in the book’s online supplement.

The NMC Horizon Reports: The NMC Horizon Project charts the landscape of emerging technologies for teaching, learning, research, and creative inquiry annually. Their reports cover trends in higher education, K–12 education, technology, museums, and academic libraries.10

Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Reports: The Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project examines how U.S. residents use the internet. They also track trends regarding views on the nation’s libraries every year in numerous reports. The project’s reports are based on nationwide surveys and qualitative research, including data collected from government agencies, technology firms, academia, and other expert venues.11

Discussion Questions

What resources are you adding to your PLN—personal learning plan? How much time will you devote daily or weekly to scanning the horizon?

OCLC Research: OCLC Research is an organization that focuses on helping libraries, archives, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions better understand a range of trends. For example, some of the organization’s recent research activities focus on metadata management (LinkedData), technology, user behavior, OER, standards, scholarly publishing, digitization, and collection sharing.12

Statistics: There are many primary sources for statistics related to libraries and other types of information organizations, offering a rich source of information to explore (see also chapter 3: “Statistical Datasets for Information Organizations” in the online supplement).

CONCLUSION

Today’s information professionals are charged with taking the reins of strategy and leading the charge for change. Hallmarks of dynamic information professionals in the twenty-first century include the ability to envision a better future, manage and lead change, and participate with their “tribe” of like-minded colleagues in building a better future—not just for their organizations but also for all information users. Choosing to make an impact is the first step. The resources described in this chapter can help professionals remain in a mode of lifelong learning—another hallmark of a great information professional. Ultimately, for information professionals to remain what they are—vital and essential hubs of their communities—they must continuously adapt and change to effectively address the ongoing changes in the world around them.

APPENDIX 3.1: LIFESTYLE AND SOCIETAL TRENDS

The following list of lifestyle and societal trends is not intended to be exhaustive, but it provides a flavor of some of the more prevalent trends and emerging issues that may impact information organizations. It is essential to keep an eye on social changes, government policy, and political trends, as issues such as health care, school funding, immigration, or national and state/provincial funding of libraries can create additional burdens on libraries to fill the gap or address the opportunities in increased attention on or funding for library programs and service portfolios.

Accessibility: Accessibility is the umbrella term for the ability to serve all users, including those with visual, auditory, learning, or mobility challenges. These issues will be at the forefront of information service delivery for years to come, especially as equitable access to digital resources increases in importance.

Digital Divide: Digital divide refers to differential access to digital resources and services caused by demographic, economic (poverty), geographic, and other issues. It is a complex issue that encompasses physical access, education, affordability, and more. Information users range from those who are the most intensive and capable web users (e.g., creating websites, writing blogs, uploading videos, and producing digital content) to those who are “inactive” participants who may be online but do not participate in social media or interactive content. Digital, semi-digital, and non-digital users will create tensions in equitable organizational strategies.

Discretionary Time Deficit: Trends over the past ten or more years suggest that “lack of time” continues to be a barrier to participation in all “discretionary” activities, including information usage. The growth in leisure time that was forecast in the 1970s has not materialized, and people are increasingly pressed for time.

Desired Use of Leisure Time: While commentators disagree on the extent to which people will have more leisure time in the future, they predict a significant shift in how people will use their leisure time.13 These projections see a relative decline in traditional recreational activities (team sports, stamp and coin collecting, etc.) and a significant increase in social networking, online entertainment, and virtual experiences in free time. Information organizations need strategies that tie their leisure collections beyond books on hobbies and recreational reading into a diversified program package.

Environmental and “Green” Concerns: There is a heightened awareness among the Millennial market for everything “eco-friendly” and “green.” This awareness may have significant implications for all aspects of information service delivery, including facility development and design, program development and delivery, materials development and processing, and information dissemination.

Family Structure and Dynamics: Statistical trends indicate a rise in nontraditional family structures (e.g., single parent, divorced parents, multiple-households, same-sex marriage, etc.), the declining predominance of two-working-parent households, a rise in commuter lifestyles, increased urbanization, and shared households. These dynamics have implications for hours of operation, asynchronous (virtual) programming, and the delivery of library programs and services.14

Health and Wellness: These concerns will continue to be a top-of-mind issue/concern to society and an increasing focus of government spending in the coming years. North American society has an aging population with corresponding health and aging issues simultaneously with a very large, young Millennial population in their child-rearing years. Information professionals who can provide accessible, high-quality health/wellness resources, or electronic information or links to other health information providers will be well positioned to meet growing demand for this type of information.

Immigration: New immigrants in search of affordable housing will continue to relocate in communities on the periphery of a country’s largest cities. Research has shown that immigrants may have different expectations of information organizations, public and social services, and technology. The public library and its partners will have a key role to play in orienting newcomers to the community and the range of services available. Information organizations are working on new immigrant orientation and partnerships with settlement agencies to drive program awareness and cardholder growth.

Information Literacy: Beyond Reading: Information organizations have a long-standing role in providing access to information and ensuring information literacy (i.e., teaching proficiency in finding information and assessing its relevance, authoritativeness, and value). There is no question about the need for information literacy in an unregulated and ever-expanding digital universe. Information organizations need to develop strategies for information fluency including the full range of digital literacies, reading literacies for all ages, and the ability to sift information for quality and usefulness in a too-much-information world (see also chapter 16: “Teaching Users: Information and Technology Instruction”).

Labor Trends: Growing employment opportunities tend to be in knowledge industries in North America including health care, technology/computer systems, professional services, and small/entrepreneurial businesses. Information organizations that can partner with other agencies to provide training and employment services and other collaborations in these areas will increase their profile and relevance in the community.

Partnership and Collaboration: Organizational partnerships are evolving and expanding, and the organization’s role in helping users navigate through the plethora of content and information available will continue to be an important one. Information organizations can make sense of multiple levels of government for citizens and residents to access the services their tax dollars pay for.

Private Schools, Alternative and Charter Schools, and Homeschooling: These options appear to be on the rise. The increased appeal for private schools, alternative and charter schools, and homeschooling imposes a challenge for many information organizations as the support systems for homework and learning. Some U.S. states have passed legislation requiring public schools to support home learners. That said, homework help is a growing part of the service portfolio for many information organizations as school library hours are cut or diminished altogether.

Smart Device Expectations: Smart devices go beyond smartphones and include tablets, phablets, and the internet of things. Those under the age of twenty-five are not “passive recipients” of education, media, or technologies; they learn differently and seek and use information differently than previous generations—having grown up in a twenty-first-century web world. The challenge for information organizations will be to engage the mobile user and adopt responsive design strategies.

Web-Savvy Information Users: Information users are increasingly participating in a variety of internet-based activities: browsing, borrowing, retrieving, downloading, and interacting with web content. Most internet users are experienced web users and have been online for more than five years. These experienced users have higher expectations of all types of information organizations. On the other hand, they may dismiss the need for information organizations altogether if they have an unclear view of how information organizations and information professionals can add value and deliver the goods.

Zoomers: The aging of the population is resulting in a new wave of older adults with different expectations, needs, and interests than the previous generation. Traditionally, seniors have been a key niche segment for many information organizations. This generation of retired baby boomers will demand more, placing pressure on information organizations to meet that challenge.

APPENDIX 3.2: TECHNOLOGY TRENDS

With rapid developments in the field of computers and information technology, predicting the future of technology as it affects information services is particularly challenging. Current trends, however, indicate that access to all forms of information and content will become increasingly associated with smaller, more powerful, and more versatile handheld wireless devices (see also chapter 25: “Managing Technology”). Some current and emerging trends and their implications for information organizations follow:

Online Learning: Although MOOCs (massive open online courses) and OER (open education resources) are creating issues that largely affect academic libraries, increasing opportunities are developing for public libraries. In the United States, many library systems have offered 24/7 learning resources that offer users online learning through access to e-learning programs, including Gale Cengage’s Gale Courses (online adult e-learning) and their accredited online high school that is offered through public libraries. Lynda.com offers technology training in a scalable way. Many users are not trying for full degrees but are ornamenting their résumés with nanodegrees, technology boot camps, online certificates, and other skills-based learning models.

Wireless Expectations: People expect all public areas, including information organizations, to have free Wi-Fi. Worktables with plug-ins for laptops or other mobile devices will be increasingly needed, and group workspaces wired for laptops are in high demand. Some information organizations are lending wireless hotspots. Some organizations are also taking part in beacon mesh networks throughout their communities or taking advantage of whitespace broadband to lower costs and increase diffusion.

Digital Download Kiosks: Kiosks started as e-vending machines that were placed in areas that could not support a full branch or high traffic areas like bus, train, and transit stations. They required power outlets and a connection to the organization’s network. Excitingly, beacons, like Apple’s iBeacon, serve as small hotspots that allow users to download e-books, audiobooks, videos, music, and games directly to their smartphones and handheld devices or tablets. Some beacons allow for twoway communications and engagement with users as well as data gathering. Others, like LibraryBox, can create a hotspot with content without the need for electricity or internet access.

Mobile Device Arena: The explosion of mobile device usage is replacing the laptop/desktop model and creating a post-PC era where BYOD, or “Bring Your Own Device,” is common.

Increasing Demand for Audio and Video Live-Streaming: These growing demands require reliable high-speed access. Users are increasingly downloading and/or transferring video and audio content to their own devices while video has begun to dominate web traffic. Recommendation systems are proliferating as a way that users make choices. Recent video streaming initiatives from Apple, Facebook, and Amazon are changing the world of video delivery along with micro-video services like Periscope and Snapchat.

Voice Response and Control: A proliferation of voice response communication tools like Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, or Microsoft’s Cortana are battling it out for keyboard-free interface.

E-Book Readership and Sales: Recent Pew Research indicates a growing influence of e-book readership.15 This phenomenon of print versus e-book sales seen over the last few years has started to slow and appears to have reached a plateau indicating that there will be a hybrid market for many more years.

Publishers, Information Organizations, and e-Books: There have been some promising pilots concerning evolving relationships between publishers and information organizations, but the challenges of accessing, owning, leasing, and affording “book” content is still a struggle. The Toronto-based start-ups Wattpad and Rakuten Kobo show the emergence of a large self-publishing portfolio in libraries and beyond.

User Contributions to Content: Information users are not only browsing, borrowing, and downloading, but they are increasingly creating and interacting with content available through the web. The information organization as publisher is a trend in some public libraries.

“Cloud” Computing: Cloud computing continues to be a major technology trend that is moving most content and software into the cloud—especially for public institutions in order to reduce costs of technology ownership. This trend places pressure on information organizations to identify cooperative solutions for information systems innovation and integration—forcing many more library systems into consortial organization structures. It will also create opportunities for greater collaboration on content acquisition and deployment.

Hardware Size Shrinking but Space Needs Growing: Although computer hardware is becoming more compact, the total amount of space for a computer workstation is not significantly reduced.

Computer Training Space and Equipment: The information organization’s role as a training center for hands-on instruction in the use of computers, application software, and internet-based resources will continue to grow.

Latest Technology Tools: 3-D printing has now reached the consumer market; consumers can now buy 3-D printers at retailers like Staples. This technology is being implemented in many makerspaces in information organizations (see also chapter 18: “Creation Culture and Makerspaces”). The Maker Movement aligns well with North American science, technology, engineering, arts, mathematics (STEAM) education goals.

Privacy: It is becoming a huge issue in some markets and within library and information science that user privacy data needs protecting, and libraries are a key place to receive privacy and computer safety advice.

Information Organizations as Centers for Technology and Innovation: The advent of the “virtual library” and technology, in general, has changed the way in which core information services are being delivered and will continue to have a major impact on future services (see also chapter 10: “Digital Resources: Digital Libraries”). Information organizations are offering more services online (and doing so at an accelerating rate by taking advantage of consortia to negotiate universal access), including virtual/digital reference services, electronic databases, and e-books. Most libraries find the majority of their usage is now virtual, but the type of usage is different. It is evolving.

APPENDIX 3.3: FACILITY AND SERVICE TRENDS

The facility and service trends discussed in this section are closely interrelated to other trends above. They point to an information organization that is actively integrated into the affairs of the community. It is an outward-looking information organization that is heavily invested in all aspects of community life and very closely linked to other community service providers. The key trends can be briefly listed as follows:

Information Organizations Are Destinations: Placemaking refers both to the process and philosophy of planning and creating a public space within a community—with a lot of thought given to cultural tourism, or “cultural capital,” and architectural design.

Information Organizations as Multiservice Providers: Information organizations are increasingly forums for community learning and expression, serving as technological, employment, business development, cultural, art, and heritage centers for their communities. Many European public libraries, such as Aarhus DOK1 in Denmark, DOK in Delft, Netherlands, and the Library of Birmingham, UK, have adopted these models. This trend has started in some North American libraries, for example, in Toronto, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Chattanooga.

Information Organizations Fostering Community Engagement: While information organizations have always been disseminators of information, innovative organizations are no longer content with one-way communication. Information organizations strengthen neighborhoods and communities by creating connections and understanding needs, going out into their communities, and fostering collaborative relationships to build relevant and responsive information services (see also chapter 17: “Hyperlinked Libraries”).

Information Organizations with Makerspaces: Provided with the space, tools, and encouragement, information organization users can come together in makerspaces to collaborate, learn hands-on skills, and create and produce music, videos, jewelry, games, robotics, electronics—and anything in between.

Information Organizations That Break the Box: Some pilot initiatives are challenging the idea of an information space. These include the Little Free Library movement, information organizations as vending machines in any location for borrowing content, bookmobiles that become book bicycles, book burros, or wireless access from a hybrid traveling car.

Information Organizations with a Customer-First Focus: Today’s information organizations are adopting a customer-first focus. For many, this has resulted in:

• improved hours of operation,

• self-checkout technology,

• online booking systems to pay fines, register for programs and computers, renew and reserve items,

• quiet spaces for study and work,

• partnership spaces—theaters, meeting rooms, social work staff, etc.,

• comfortable spaces for socializing,

• light food and beverage services,

• expanded programming and dedicated resources for target groups (e.g., children, teens, seniors, cultural groups, students, etc.),

• helpful, available staff who engage with the user in the information organization (“walk the floor”), and

• information-rich technology and training opportunities.

Not only do these improvements better serve the organization’s customers, but they also result in an operationally efficient organization and a functional work environment for staff.

1. George Couros, “Characteristics of a Change Agent,” The Principal of Change, last updated January 26, 2013, http://georgecouros.ca/blog/archives/3615.

2. Apple, Inc., iBeacon, accessed September 6, 2017, https://developer.apple.com/ibeacon/.

3. Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), “Academic Library Statistics,” 2015, http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/trends; Association of Research Libraries (ARL), “Statistics and Assessment Surveys (Canada & US),” 2017, https://www.arlstatistics.org/home; Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), “Research Data Collection,” 2014, https://www.imls.gov/research-evaluation/data-collection/public-libraries-survey; National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), “Surveys and Programs,” 2017, https://nces.ed.gov/; Public Library Association (PLA), “PLDS and PLAmetrics,” 2017, http://www.ala.org/pla/resources/publications/plds; Counting Opinions, 2017, http://www.countingopinions.com. In the United States and Canada, Counting Opinions is a private sector consulting service that specializes in library data and satisfaction and effectiveness studies.

4. MarketingCharts, “American Households Are Getting Smaller—and Headed by Older Adults,” 2012, http://www.marketingcharts.com/traditional/american-households-are-getting-smaller-and-headed-by-older-adults-24981/.

5. See Los Angeles Public Library, http://www.lapl.org/diploma.

6. Roger Levien, “Confronting the Future: Strategic Visions for the 21st Century Public Library,” American Library Association Policy Brief, no. 4 (2011), http://www.ala.org/offices/sites/ala.org.offices/files/content/oitp/publications/policybriefs/confronting_the_futu.pdf.

7. HathiTrust Digital Library, 2017, https://www.hathitrust.org/.

8. Digital Public Library of America, 2017, https://dp.la/.

9. Europeana, “Europeana Collections,” 2017, http://www.europeana.eu/portal/en.

10. New Media Consortium, “NMC Horizon Project,” 2017, https://www.nmc.org/nmc-horizon/.

11. Pew Research American and Life Project, “Libraries,” 2017, http://libraries.pewinternet.org/.

12. Online Computer Library Center, “OCLC Research,” 2017, http://www.oclc.org/research.html.

13. Mark Aguiar and Eric Hunt, “Measuring Trends in Libraries: The Allocation of Time over Five Decades,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 122, no. 3 (2007): 969–1006.

14. MarketingCharts, “American Households Are Getting Smaller.”

15. Andrew Perrin, “Book Reading 2016,” Pew Research Center, December 1, 2016, http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/09/01/book-reading-2016/.