Michael J. Krasulski

Chapter 15, “Accessing Information Anywhere and Anytime: Access Services,” identifies the many services that go into everyday operations in providing access to the information organization’s resources and services. Access services retains its historical roots in circulation and collection management but continues to change in response to technological and institutional changes. As a leader in access services and coeditor of Twenty-First Century Access Services: On the Front Line of Academic Librarianship, Michael Krasulski brings his extensive knowledge of this topic to his well-rounded discussion of access services.

Central to any discussion of access services is the integrated library system (ILS) because it handles various functions throughout the information organization (e.g., acquisitions, cataloging). Krasulski explains how the ILS works to facilitate a wide range of access services functions beyond collection management and circulation, such as maintaining privacy and managing the user database. Krasulski explains other technological changes in access services; for example, automated storage and retrieval systems have brought a technological solution to the shelving and housing of physical collections. The chapter covers other important topics including resource sharing and course reserves, as well as assessment.

Access services demands trained staff committed to creating positive interactions with users, notes Krasulski. Because of the multiplicity of roles often included in access services, information professionals in this field may need to be comfortable with everything from building maintenance to copyright, from security to signage. The takeaway from this chapter is that no matter what title the information professional possesses, this person will have a direct impact on the effectiveness of access services within his or her organization and therefore the user experience.

* * *

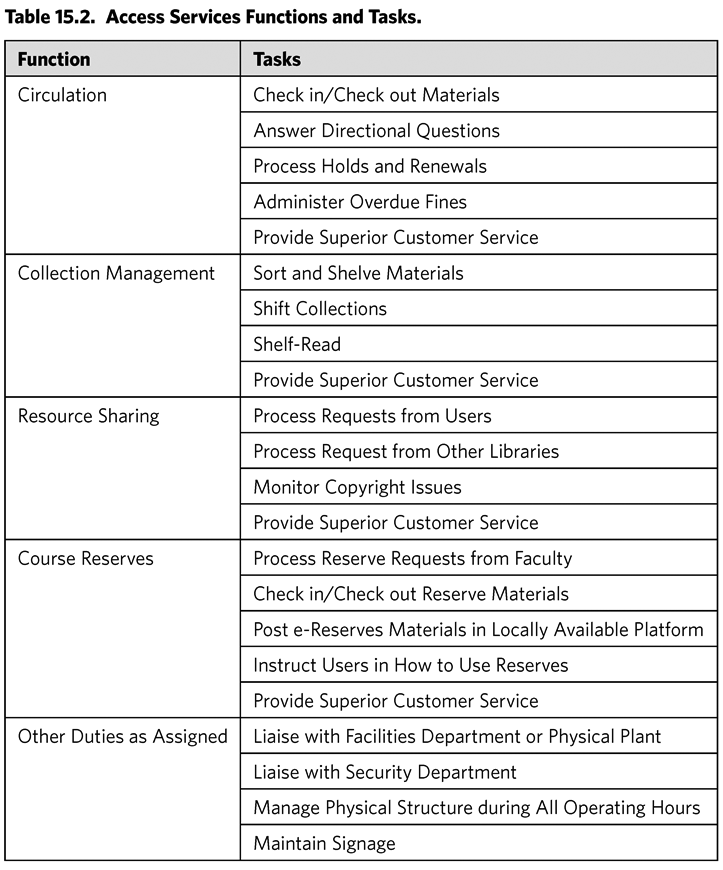

Access services is a catchall term to describe the circulation, course reserves, document delivery, collection management, and related tasks and functions found within an information organization.1 See appendix 15.1: “Access Services Functions and Tasks.” These often unseen and underappreciated functions are central to an information organization’s daily operations, and have been for a very long time. The exact impetus for the creation of access services as a concept is unclear and debatable; for example, few information organizations used the term access services before 1981.2 Regardless of its exact origins, there is some consensus that the creation of access services signaled “more emphasis on the user as a consumer of information who needs access to information in a variety of formats.”3 The implication is that access services help facilitate access to materials users need in a timely manner regardless of the source. After completing this chapter, the reader should have an understanding of circulation, collection management, resource sharing, course reserves, and related functions that are most common within information organizations, and have some familiarity with leading and assessing access services.

“Access services help facilitate access to materials users need in a timely manner regardless of the source. „

FACILITATING ACCESS

Access services is a sum of many disparate parts, and its operations impact every user of the information organization. In reflecting upon his over thirty years of experience in the profession, James G. Neal, university librarian emeritus, Columbia University, and American Library Association president (2017–2018) once noted:

Access services opens the library in the morning and secures it at night. It serves as our essential link to campus operations, like building maintenance, security, and food services. It oversees the quality and usability of library space. It manages our physical collections. . . . It circulates materials and technologies and supports the special facilities for distinctive formats, for group and class use. . . . It supports teaching and learning through traditional and electronic reserves, enabling a strong presence for libraries in course management systems and online education. It is the front line of our consortial relationships, managing an expanding array of regional, national and global interlibrary loan and document delivery services that support quality scholarship. It is the early warning system for building environmental issues and collection preservation and damage problems. It is the gatekeeper for the authorization and authentication of library users to the vast array of electronic resources we have leased and acquired. Access services is essential, fundamental, and pervasive.4

The functions that Neal details above are indeed essential—fundamental to and pervasive within the information organization. Besides a collection of functions and tasks, access services can also be an administrative umbrella where aforementioned tasks and functions reside within the information organization. The absence of access services from the organizational chart does not mean access services is absent from the information organization. Rather, access services functions can be diffused administratively across and throughout the organizational structure. As such, access services can appear to assume the persona of a refuge for services and functions that do not fall clearly under any other category.5 The fluidity of access services means being all things to everyone. The various functions described in this chapter are found in information organizations, in varying incarnations, regardless of type.

“The absence of access services from the organizational chart does not mean access services is absent from the information organization. Rather, access services functions can be diffused administratively across and throughout the organizational structure. „

Circulation and the Integrated Library System

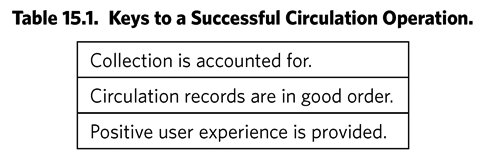

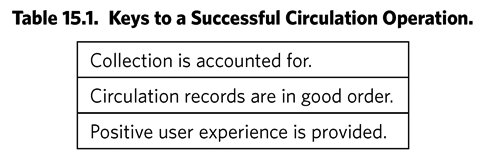

Circulation and access services are often used interchangeably since access services tends to be thought of as circulation activities plus other functions. Circulation fulfills the vital roles of administering who can use the information organization and what they can use therein, facilitating the access to physical items between the information organization and the user, and being able to identify the location of any item in the physical collection at all times. All of these roles are, in varying degrees, automated in and administered through the information organization’s integrated library system (ILS) (see also chapter 25: “Managing Technology”). Different modules exist within the ILS to handle various functions throughout the information organization (e.g., acquisitions, cataloging). The ILS demonstrates the interdependency of access services with other departments within the information organization. For example, cataloging and acquisitions, often labeled together as technical services, process materials into the ILS, and the systems department administers the ILS (see also chapter 12: “Metadata, Cataloging, Linked Data, and the Evolving ILS”).

The ILS manages the information organization’s user database and tracks what items have been loaned out, to whom, and when those items are due back, as well as the locations of items within the building. Each user has a unique record in the user database containing the user’s contact information, as well as information regarding any library use activity. The American Library Association’s (ALA) “Library Bill of Rights,” article IV, states, “Libraries should cooperate with all persons and groups concerned with resisting abridgement of free expression and free access to ideas”6 (see also chapter 35: “Intellectual Freedom”). One interpretation of Article IV is “when users recognize or fear that their privacy or confidentiality is compromised true freedom of inquiry no longer exists”7 (see also chapter 34: “Information Privacy and Cybersecurity”). The library has a responsibility to maintain the privacy and confidentiality of all user records. Not only is this a courtesy to the library’s users, in the United States, forty-eight states require by law that libraries maintain user confidentiality in its records. Many other countries have adopted such laws as well.8

As well as managing the user database, the ILS automates the bookkeeping and recordkeeping aspects of circulation, which include overdue fines, item renewals, and communications to users concerning overdue and recalled material via various means, including e-mail or short message service (SMS). Each information organization has its own loan rules and policies that govern who can borrow what and for how long. For example, in academic libraries, undergraduate users may have twenty-eight days to borrow an item, while it is not uncommon for faculty to have a semester-long borrowing period. The ILS takes the guesswork out of managing, administering, and remembering these rules and policies since the ILS is customizable to handle such institutional variability. The ILS is not just for managing traditional book and journal collections. Information organizations that circulate e-reading devices, laptops, audiovisual materials, and even Wi-Fi hotspots and makerspace equipment can track these materials in the ILS.9

It is common for circulation functions to be located at or near an information organization’s main entry/exit point. Consequently, access services, and circulation in particular, can be the first, and often only, point of contact between the majority of users and the organization.10 To state this reality another way, access services is the information organization’s original user interface. It is here that perceptions about the information organization are formed. Consider the variety of interactions at any circulation desk in any information organization on a given day. There is the potential for an interaction to go wrong. Such situations may be the result of a serious user infraction, like theft or mutilation of organizational property. Others are more benign, like enforcing fine policies. It is imperative for access services staff to be trained in creating a positive user experience (see also chapter 14: “User Experience”). Negative user interactions reflect poorly on the information organization. As corporations have learned in today’s digitally connected age, negative customer interactions can become viral thanks to various Web 2.0 technologies, such as blogging, Twitter, Yelp, or Facebook. Experiences with access services staff often shape how users view the organization.

The increased availability of electronic resources and the decline in book circulation have led many information organizations to rethink the role of the circulation desk. There has been a movement toward one-stop shopping, particularly in college and university libraries, by combining the circulation desk with the reference or information desk11 (see also chapter 7: “Learning and Research Institutions: Academic Libraries”). Streamlining service and freeing staff to do other things have been reasons for organizations to add self-check terminals at circulation desks, a change that can also improve service. These terminals allow users to check out materials with little or no staff involvement. However, no system is fool-proof; errors may occur and staff intervention may be needed. Thus, self-check machines are typically placed in close proximity to the circulation desk. While technologies, such as the ILS and self-check, have drastically changed how a circulation department operates, what has remained the same is the need for outstanding user interactions—whether that interaction is in person, over the telephone, or online.

“Access services is the information organization’s original user interface. It is here that perceptions about the information organization are formed. „

Collection Management

The storage, retrieval, and maintenance of the organization’s physical collections, also known as collection management, is a vital access services function (see also chapter 24: “Managing Collections”). Depending upon the organization, collection management functions may fall to volunteers, student workers, or paraprofessional staff. These employees typically:

• shelve returned items or new items added to the collection,

• check, from time to time, the items on the shelves to ensure items are shelved properly (often referred to as shelf-reading), and

• adjust items already on the shelves to accommodate changes in collection size, often referred to as shifting.

The decline of book circulation, the ubiquity of journals available electronically, and the calls to repurpose shelving space for other purposes have caused information professionals to experiment with various storage options that maximize existing space for the organization’s collections. Compact shelving stores more materials than traditional shelving because the space between the shelving units is largely eliminated. Think about having the entire book stacks compressed together and then having the ability to open a section of stacks to retrieve a needed book or journal. That is essentially how compact shelving works. Users still go to the shelves, call number in hand, and retrieve the item. However, instead of walking into the stacks, users operate a manual or automatic shelving system to open up the exact access point where the needed item is located.

Automated storage and retrieval systems (AS/RS) have brought a technological solution to the shelving and housing of physical collections. The first installation of such a system was at California State University, Northridge. The James B. Hunt Library at North Carolina State University is another example; it opened in January 2013 to much excitement. Because the building is designed to have more open and collaborative study and work space, the book stacks are largely removed and out of sight. Items are kept in a high-density storage facility within the library and retrieved using bookBot (a robotic, automated book delivery system). Users select the item they wish to use in the online catalog, and within minutes, the item is available for pickup near the library’s entrance. The online catalog permits virtual browsing so users can view like items that would be on the shelves around the item requested. The bound journal collection also utilizes the bookBot system. Users place a request for an article, and the article is delivered by e-mail in about twenty-four hours. AS/RS technology allows the Hunt Library collection to take up about one-ninth the space it would if the same items were stored on traditional shelves. Another notable example of AS/RS technology at work is the book train at the New York Public Library.12

Remote storage, as the term suggests, is the removal of physical collections to a site separate from the information organization. The distances can vary by organizations, with the remote storage sometimes located in a building next door and other times in another state. Users locate items in the catalog, request them, and then have these items delivered to a service point, likely the circulation desk, for pickup. Remote storage meets the goal of opening space for other purposes; however, users lose the ability to browse the shelves and may experience a delay between the placement of the request and the delivery of the item.13 While remote storage removes the serendipitous person’s ability to interact with the books on the shelves, the long-term future for preservation of books is actually better because remote storage facilities are often newer and are usually designed with careful temperature and humidity controls in mind (see also chapter 13: “Analog and Digital Curation and Preservation”).

Resource Sharing

Resource sharing, which is sometimes known as interlibrary loan (ILL), is the process that supplies users with materials not readily available at their own institution. A user places a request for a desired item. If the item is owned by another information organization, a request to borrow the item is sent; when the item is received, it is checked out to the patron for a loan period determined by the lending organization. Resource sharing complements materials owned by the information organization since the information needs of users are enhanced by the ability to obtain items outside those in their local collections. Increasingly, users are also allowed to request items that are owned in their local collections but that are otherwise unavailable. This allows multiple users to research the same topic without competing for resources,14

“Resource sharing complements materials owned by the information organization since the information needs of users are enhanced by the ability to obtain items outside those in their local collections. „

Resource sharing services offered for those materials that are held locally is called document delivery. Document delivery services were first offered in large academic libraries as a convenience to save faculty users the time and trouble of coming into the library and pulling and copying print journal materials themselves. Document delivery services allow faculty users to place requests and have these materials delivered to faculty offices via campus mail or scanned and e-mailed directly to them. The growth of remote storage collections in both academic and public libraries and the popularity of distance education in academic institutions have expanded the need of document delivery services. Usually, users place requests through the same resource-sharing system used for items not owned locally. Document delivery is also a way to abate any criticism that items in remote storage are not accessible. Additionally, document delivery demonstrates in a clear and convincing way that access services contributes to the success of the information organization by supporting distance education users.

Resource sharing is not without its costs and requires a significant investment on the part of the information organization in both human and financial resources. Staff intervention is required to locate, pull, and scan materials, especially when an article or book chapter (rather than the full publication) is requested. Additionally, the arranging, tracking, and managing of requests can be labor intensive, and many large information organizations invest in a separate information management system to administer resource sharing tasks. Shipping costs, fees to acquire items, copyright fees, fees for lost or overdue items, and costs from article providers are often absorbed by the information organization.

Discussion Question

Resource sharing and course reserves activities can infringe on copyright. In what ways can access services practitioners mitigate these potential infringements?

While book circulation may be declining, the need for resource sharing in information organizations is growing. The reason for this paradox rests in the fact that users want to use the information organization and its services, but not necessarily the materials provided for them on physical shelves. Additionally, advances in resource-sharing technologies have often reduced turnaround times for article and other nonreturnable requests from days to mere hours.15

Course Reserves

Course reserves are commonly found in college and university settings. Reserves can be either physical objects available at a service desk or digital resources available remotely, typically through a password-protected portal (e-reserves). When available at the service desk, access services staff purchase new or retrieve already owned materials from the stacks at the request of faculty members and place these in a restricted area, often behind the service desk. The materials are added to the faculty members’ course listings, and students can retrieve the items at the library. The loan period is generally short, typically no more than a few hours, and often accompanied by the threat of high late fees to ensure prompt return. Formats can include books, journal articles, DVDs, and even anatomical models. Course reserves can also utilize the academic library’s laptop and e-reader or other nontraditional format item-lending programs when these types of programs are locally available. Placing materials on reserve provides an ideal solution to the problem of managing materials in high demand. The service allows users equal access to the same materials.

Discussion Questions

Some have called access services the original library user interface. How can access services shape, both positively and negatively, the user experience? In what ways can access services help provide a positive user experience?

The rise of distance education and the general desire to provide an excellent user experience have prompted many academic libraries to provide remote access to reserve materials in digital form. In terms of process, electronic reserves differ considerably from print reserves. Faculty still identify the materials they want placed on reserve, but instead of photocopying those materials and housing them behind a service point, library staff make digital copies and make them available online (either hosted by the library or in the college or university’s course management system) or link directly to e-resource holdings.16 The library is still involved in the processing and maintenance of this service but its efforts are largely unseen by the user.

Other Duties as Assigned

The persona of access services as being all things to all people is perhaps best evidenced through the myriad ways in which it supports the information organization. Access services, as a reflection of the needs and idiosyncrasies of the larger information organization, can make discussions about common experience across institutions difficult. Yet, it is not uncommon for access services practitioners to assume the personas of library security, copyright experts (see also chapter 31: “Copyright and Creative Commons”), and building managers within their information organizations.

Access services can take on the persona of library security since it is often responsible for enforcing and defending various policies of the information organization, such as entrance, fines, food and drink, noise, and usage policies. Given the omnipresent nature of access services, it makes sense for access services to take on these responsibilities. Sometimes enforcing these policies can result in conflict. Frontline access services staff are usually several administrative levels below where policy or decisions are made, so this can create frustration when the reasons behind the policy/change are not fully communicated to the staff and when frontline staff do not have the opportunity to provide feedback to the administration before a policy is implemented. To successfully navigate these proverbial minefields, access services practitioners need to be familiar with both the information organization’s current policies and the various arguments made against said policies, and need training on the best ways to defuse potential conflicts with users.

Access services practitioners often have a fluency in copyright rules because of the very nature of resource sharing and course reserves. Within the information organization, it is not uncommon for others to look to access services staff to serve as the copyright “experts.” At the very least, those working in document delivery or course reserves must have a working knowledge of fair use and the various guidelines around fair use. It has been over forty years since the last major changes to the American copyright laws were made. Ever since, content producers and information practitioners have attempted to draw up guidelines or model practices to no avail, since neither side could agree. Information organizations often argued for more conservative interpretations of copyright law to remain in the good graces of the content providers.

TEXTBOX 15.3

Copyright Clearance Center and Association of American Publishers v. Georgia State University

In 2008, several publishers, with the backing of the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) and the Association of American Publishers (AAP) brought suit against Georgia State University, challenging the University’s use of copyrighted material for electronic course reserves. The original ruling and the subsequent appeals largely agreed with Georgia State University’s copyright interpretations. Even after this court case, many questions regarding copyright and resource sharing and course reserves remain. It is incumbent upon access services practitioners to continue to monitor the situation and apply any changes as necessary.

The persona of the building manager arises from access services staff being present during all the operating hours of the information organization. Access services often serves as the liaison between the information organization and the institution’s facilities or physical plant department (see also chapter 23: “Innovative Library and Information Services: The Design Thinking Process”). Problems with the building are typically reported to access services staff first.17 Additionally, access services staff possess a unique perspective from their frontline service point and are able to oversee certain facility-related issues within an information organization operation, for example, 24/7 staffing and the creation of signage for effective wayfinding.

Just as an information organization’s electronic resources are available twenty-four hours a day, the demand for access to physical collections has resulted in many academic libraries remaining open for twenty-four hours for five, or in some cases seven, days a week. Providing twenty-four-hour access is no small undertaking. The barrier to providing such a service often comes down to staffing overnight hours. Sometimes full-time access services staff take the overnight shifts, while other times it is the responsibility of student assistants or students receiving work-study funding. If few or no services are provided in these overnight hours, a member of the organization’s security department may be utilized to provide adequate staffing. The solution is based on local conditions, including funding (see also chapter 21: “Managing Budgets”) and building design considerations.18

The creation and subsequent revisions of signage for the organization can fall to access services staff. Responsibility for signage is a result of maintaining the signage at the ends of ranges of shelving units indicating the first and last call numbers of each row. Additionally, access services professionals should think about signage as a response to frequently asked questions. Clearly worded and well-placed signage can greatly reduce the number of directional questions received at service points and communicates a welcoming and inclusive atmosphere.19

ASSESSING ACCESS SERVICES

The above sections serve as an introduction to the various access services functions and illustrate ways access services contributes to the success of the information organization. However, contributing to the success of the information organization is no longer enough to remain vital or essential since the continuing relevance of information organizations is being questioned as never before in many arenas (e.g., academia and local and state governments). Every function or department in the information organization, access services included, must demonstrate and document its contributions in purposeful and meaningful ways. The process of systematically evaluating and demonstrating success and implementing improvement as needed is called assessment. As information organizations strive to become more user-centric, they are paying increasing attention to assessing user needs and designing services to meet those needs. Access services functions are often at the center of these assessment efforts. Additionally, academic libraries, for example, are required to participate in formalized assessment efforts across their campuses since accrediting bodies mandate that institutions of higher learning organize, document, and sustain assessment activities in order to, as the Middle States Commission on Higher Education has instructed its member institutions, demonstrate “periodic assessment of mission and goals to ensure they are relevant and achievable”20 (see also chapter 28: “Advocacy”).

“Every function or department in the information organization, access services included, must demonstrate and document its contributions in purposeful and meaningful ways. „

The most basic assessment measure is documenting use—that is, how and to what extent the services and functions of the information organization are being used (see also chapter 26: “Managing Data and Data Analysis in Information Organizations”). Put simply, gauging use involves gathering usage totals from various functions over a period of time, typically a year, compiling these data in a chart or table, and then comparing to data from the previous period. Such data can be gathered in a variety of ways, including entrance and exit counts or lending and borrowing statistics from both circulation and resource sharing.

Evaluating and tracking use over time are important; however, these data do not inform administrators if users are satisfied with the quality of services provided. User satisfaction studies, often performed via surveys, can answer such questions and help the organization measure the value of their services. Information organizations may choose to develop their own survey instrument or elect to use a standardized survey. Each approach has its own advantages. An instrument developed in-house is certainly cheaper and questions can be tailored specifically to the needs of the information organization. While a standardized survey is more expensive, these tools have the advantage of allowing for benchmarking across organizations. Two major survey instruments are LibQUAL+ and LibSat. LibQUAL+, developed by the Association of Research Libraries (ARL), asks respondents to rate a library on twenty-one different qualities that focus on quality of service, information access, and the library as place. Respondents also rate the minimum level of service they would expect versus the actual level received. ARL administers LibQUAL+ and provides initial analysis of the results for the library. LibSat, developed by Counting Opinions, is more focused on public libraries. LibSat is a continuous survey tool that measures user satisfaction and expectations and the importance of those expectations to users. Regardless of which instrument is used, user satisfaction studies provide valuable data that cannot be extrapolated from usage statistics alone.21

After collecting data, the information organization should close the assessment loop, that is, use the results to improve, change, or realign services. For example, knowing when users come to the building can be helpful in determining how much staffing is needed at a service point. Additionally, these data can also be useful in setting appropriate service hours or demonstrating the appropriateness of current levels of service should there be a clamor for additional service. User satisfaction data may reveal that underused services need to be promoted more heavily or are no longer needed. The utilization of assessment data varies from one information organization to the next. If improvements are made, the information organization should communicate those changes to the user.

LEADING ACCESS SERVICES

As stated earlier in this chapter, access services is both a collection of functions and tasks as well as an administrative umbrella within an information organization. Those tasked with leading access services may be paraprofessionals with significant experience or information professionals who have library and information science master’s degrees. Generally speaking, a dedicated course in access services is not taught in ALA-accredited library and information science graduate programs, though aspects of access services may be covered elsewhere in the curriculum.22 A recent study has shown that access services professionals typically learn the skills directly related to access services on the job.23 That is not to suggest, however, that library and information science education has no role in the development of access services professionals.

The same study showed that higher order managerial skills are equally as important as access services specific skills to the success of the access services information professional. The overwhelming majority of respondents reported that the ability to formulate policies; delegate responsibilities (see also chapter 37: “Leadership Skills for Today’s Global Information Landscape”); determine priorities; supervise and evaluate staff (see also chapter 22: “Managing Personnel”); utilize existing resources effectively; and collect, calculate, and analyze statistics were important to the success of the access services professional.24 Practitioners are likely to be exposed to these types of management and statistical skills during their library and information science educational experience.

Additionally, respondents were asked about their professional backgrounds in information organizations before becoming access services professionals. The study found no clear path to becoming an access services professional.25 Some of the respondents began their careers in access services paraprofessional positions and then moved into more administrative roles, while others began in other areas of the information organization, typically in reference or technical services, and moved into access services after sharpening their administrative skills. Although there is no single path leading to access services functions or units, the study demonstrates that both work experience and course work are necessary to acquiring the necessary skill sets. Students interested in access services should consider taking courses related to assessment, management, and statistics. Additionally, students should seek volunteer or intern opportunities in an access services unit. Having hands-on experience as well as the theoretical underpinnings gained from course work will provide a sound foundation for any access services practitioner.

CONCLUSION

Access services has moved well beyond the circulation desk to fill vital roles in the continued success of information organizations by connecting users with resources. As Trevor A. Dawes and the author of this chapter have argued, the present state of access services can be best summed up as “Like always, like never before,” which was used in the short-lived tagline to the mid-2000s Saturn automobile commercial. “Like always” because access services retains its historical roots in circulation and collection management and “like never before” because access services continues to adjust and change in response to technological and institutional changes.26

These types of changes will continue as the information organization continues to find its place in a twenty-first-century reality. However, there are several clear trends in access services that are worth noting:

• Coupling of information or reference desks and circulation desks into one service point is increasing. In organizations that have coupled their service points, access services staff tend to be present at the desk.

• Resource sharing usage continues to increase as information organizations continue to cancel journal subscriptions due to ever-increasing costs.

• Information organizations are exploring shared remote storage spaces and collections.

• Course reserves in academic libraries are declining as the responsibility is shifted to faculty end users.

• Access services practitioners are expected to educate their users on the nature of fair use, specifically, and copyright law.

• Access services work is becoming more interdependent, further blurring the lines between the various access services tasks and functions.

• Excellent customer service skills continue to remain paramount.27

Regardless of whether these predictions prove correct, one can be assured that access services will continue to grow, change, and adapt to meet the needs of a robust twenty-first-century information organization, and access services will continue to assume new responsibilities, sometimes finding itself in unfamiliar territory.

APPENDIX 15.1: ACCESS SERVICES FUNCTIONS AND TASKS

1. Duane Wilson, “Reenvisioning Access Services: A Survey of Access Services Departments in ARL Libraries,” Journal of Access Services 10, no. 3 (2013): 153.

2. Trevor Dawes, Kimberly Burke Sweetman, and Catherine Von Elm, Access Services: SPEC Kit 290 (Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 2005), 18.

3. Mary Anne Hansen, Jakob Harnest, Virginia Steel, Joan Ellen Stein, and Pat Weaver-Myers, “A Question and Answer Forum on the Origin, Evolution and Future of Access Services,” Journal of Access Services 3, no. 2 (2005): 15.

4. James Neal, “Foreword,” in Twenty-First-Century Access Services, ed. Michael J. Krasulski and Trevor A. Dawes (Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries, 2013), vii.

5. Nora Dethloff and Paul Sharpe, “Access Services and the Success of the Academic Library,” in Krasulski and Dawes, Twenty-First-Century Access Services, 174.

6. “Library Bill of Rights,” American Library Association, June 30, 2006, http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/librarybill.

7. “Privacy,” American Library Association, July 7, 2006, http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/librarybill/interpretations/privacy.

8. “State Privacy Laws Regarding Library Records,” American Library Association, May 29, 2007, http://www.ala.org/advocacy/privacyconfidentiality/privacy/stateprivacy; and see Zdzislaw Gebolys and Jacek Tomasczczyk, Library Codes of Ethics Worldwide (Berlin: Simon Verlag fur Bibliothekswissen, 2011).

9. Jenny Xie, “Two Major Public Library Systems Are about to Start Lending Wi-Fi Hotspots,” CityLab, June 23, 2014, http://www.citylab.com/cityfixer/2014/06/two-major-public-library-systems-are-about-to-start-lending-wi-fi-hotspots/373233/; and Bringham Fay, “MIT Libraries and MIT MakerWorkshop Launch Equipment to Go,” MITNews, March 9, 2017, http://news.mit.edu/2017/mit-libraries-and-mit-makerworkshop-launch-equipment-to-go-0309.

10. Mary Ann Venner and Seti Keshmiripour, “X Marks the Spot: Creating and Managing a Single Service Point to Improve Customer Service to Maximize Resources,” Journal of Access Services 13, no. 2 (2016): 104.

11. Pixey A. Mosley, “Assessing User Interactions at the Desk nearest the Front Door,” Reference & User Services Quarterly 47, no. 2 (2007): 160.

12. Jay Price, “NCSU’s Hyper-Modern James B. Hunt Jr. Library Poised to Open,” News Observer, December 18, 2012, http://www.newsobserver.com/2012/12/18/2553438/ncsus-hyper-modern-new-james-b.html; and Corey Kilgannon, “Below Bryant Park, a Bunker and a Train Line, Just for Books,” New York Times, November 21, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/21/nyregion/new-york-public-library-book-train.html.

13. Dethloff and Sharpe, “Access Services,” 180–81.

14. Bradley Tolppanen, “A Survey of Current Tasks and Future Trends in Access Services,” Journal of Access Services 2, no. 3 (2004): 7–8.

15. John B. Horrigan, “Libraries 2016,” September 6, 2016, PewResearchCenter, http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/09/09/libraries-2016/, 11; Shaneka Morris and Gary Roebuck, ARL Statistics 2014–2015 (Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 2017), 84, 89, 94 passim; Ian Reid, “The 2015 Public Library Data Service: Characteristics and Trends,” May 2016, Counting Opinions, https://storage.googleapis.com/co_drive/Documents/PLDS/2015PLDSAnnualReportFinal.pdf, 2, 5.

16. Steven J. Bell and Michael J. Krasulski, “Electronic Reserves, Library Databases and Courseware: A Complementary Relationship,” Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery, & Electronic Reserves 15, no. 1 (2004): 85.

17. Stephanie Atkins Sharpe, “Access Services within Campus and Library Organizations,” in Krasulski and Dawes, Twenty-First-Century Access Services, 129–30.

18. David W. Bottorff, Katherine Furlong, and David McCaslin, “Building Management Responsibilities for Access Services,” in Krasulski and Dawes, Twenty-First-Century Access Services, 88–89.

19. Ibid., 90–91.

20. Standards for Accreditation and Requirements of Affiliation (Philadelphia: Middle States Commission on Higher Education, 2013), 4.

21. David K. Larsen, “Assessing and Benchmarking Access Services,” in Krasulski and Dawes, Twenty-First-Century Access Services, 196–97.

22. David McCaslin, “Access Services Education in Library and Information Science Programs,” Journal of Access Services 6, no. 4 (2009): 485.

23. Michael J. Krasulski, “‘Where Do They Come From, and How Are They Trained?’ Professional Education and Training of Access Services Librarians in Academic Libraries,” Journal of Access Services 11, no. 1 (2014): 23.

24. Ibid., 21.

25. Ibid., 24.

26. Trevor A. Dawes and Michael J. Krasulski, “Conclusion,” in Krasulski and Dawes, Twenty-First-Century Access Services, 243.

27. Ibid., 244–45.