Martin L. Garnar

Chapter 30: “Information Ethics” offers a foundation for understanding the ethical principles that lie at the core of the information professions. Martin L. Garnar, past chair of the ALA Intellectual Freedom Committee and Committee on Professional Ethics, defines the terminology for discussing ethics, explains and identifies different ethical theories and principles that inform the profession’s ethical codes, discusses options for decision making, and highlights future trends and implications for ethical thinking.

Garnar defines ethics “as a set of principles that guide decision making in a specified setting.” He notes that when ethics are shared, the underlying principles must also be shared and agreed upon by those involved. Within the information professions, professional ethical codes have been established by several professional associations. Garnar examines the shared ethical principles across four professional associations in the information field. He further raises the issue of how well these ethical codes have held up given all the technological changes. He carefully examines issues pertinent to changes in technology, including filtering, net neutrality, and equality of access, and raises questions about the ethical issues involved. These questions lead to more questions, which, Garnar notes, is often the state of ethical dilemmas.

These ethical codes provide a useful framework that can assist in decision making on central issues in the information professions. However, knowing ethical codes does not necessarily give answers, particularly since the ethical codes are intentionally lacking in specificity. Given this challenge, information professionals need to think carefully before applying ethical principles to current situations, and they may need some help. Knowing when and where to get this help is important. Garnar provides the reader with resources that information professionals may access for guidance.

* * *

Information ethics is “a field of applied ethics that addresses the uses and abuses of information, information technology, and information systems for personal, professional, and public decision making.”1 For information professionals, this subset of ethics has the most direct application to their daily work, and its primary concerns are well represented in the profession’s ethical statements. By understanding the ethical principles at the core of the information science profession and by referring to those principles when making decisions or facing dilemmas, information professionals can strive to ensure that their everyday actions are consistent with the field’s professional values. In addition, discerning how those principles apply to new trends and situations helps keep the profession vital and relevant in a constantly changing world. After completing this chapter, the reader should have an understanding of how to:

• define the terminology for discussing ethics,

• explain different ethical theories,

• review the principles that inform the profession’s ethical codes,

• identify evidence of those principles, and

• discuss future trends and implications for ethical thinking.

INFORMATION ETHICS: KEY CONCEPTS

Defining terms is the first step in understanding ethics. For the purposes of this chapter, ethics is defined as a set of principles that guide decision making in a specified setting. Ethics can be personal or shared, which impacts the source of the principles at the heart of an ethical system. Principles may also be referred to as morals, values, or beliefs—and people may have these instilled by their family, culture, and society. People may also choose to adopt their own principles based on personal experience and study. When ethics are shared, such as in a professional setting, the underlying principles must also be shared and agreed upon by those involved. As different settings may have distinct areas of concern, there are subsets of ethics, such as information ethics, which may be tailored to various fields.

ETHICAL THEORIES

Before ethics can be approached from a professional perspective, it is important to understand different theories for applying ethics. Though there are multiple ethical theories, this chapter focuses on three dominant schools of thought: utilitarianism, deontology, and the ethics of care.

Utilitarianism

As defined by Henry R. West, utilitarianism is “the theory that actions, laws, institutions, and policies should be critically evaluated by whether they tend to produce the greatest happiness.”2 First espoused by Jeremy Bentham, utilitarianism is associated closely with John Stuart Mill, whose writings popularized the concept.3 A layperson’s approach to utilitarianism may be summed up by the exchange between Captain Kirk and Mr. Spock in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, when Spock tells Kirk why he is sacrificing his life in the damaged engine room: the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few [or the one]. Something that is beneficial for the majority is ethically acceptable if the people disadvantaged by such a decision are in the minority. Critics of utilitarianism observe that negative consequences can too easily be justified in this system of thought.

“The utilitarianism theory emphasizes that ‘something that is beneficial for the majority is ethically acceptable if the people disadvantaged by a decision are in the minority.’„

Deontology

Deontology, from the Greek deon meaning duty, refers to an ethical system based on adherence to rules (i.e., duty-bound to follow the rules). Immanuel Kant4 is considered to be the preeminent proponent of a deontological approach to ethics. In contrast to utilitarianism, deontology focuses not on the consequences of a decision, but on the rightness of the action taken. An action is ethical if the rule guiding the action depends on an underlying principle of validity as applied to everyone regardless of the consequences.5 Deontology falls short when all the choices of action are right, leaving the actor in the difficult position of having to decide which rule to break in order to preserve another rule.

“In contrast to utilitarianism, deontology focuses not on the consequences of a decision, but on the rightness of the action taken.„

Ethics of Care

Another approach to ethical thinking is care-based ethics, which may be easily summed up with what is commonly known as the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Though often associated with Christianity, this tenet can be found throughout a variety of world religions and philosophical traditions, including Confucianism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, and classic Greek and Latin texts, so considering it a universal value is not beyond reason.6 Additionally, the “ethics of care”7 is a feminist concept offered as a correc tive to the dominant paradigms of utilitarianism and deontology, as both of those approaches represent the patriarchal hegemony in modern ethical thought.

“Given the service orientation of the library and information science professions, a care-based approach to ethical thinking can be seen as complementary to overall goals.„

Given the service orientation of the library and information science professions, a care-based approach to ethical thinking can be seen as complementary to overall goals. However, as with other approaches to ethics, flaws can be found with care-based thinking. “Do unto others” stops being effective when the other is an evildoer. Even the Platinum Rule (“Do unto others as they themselves would have done unto them,” or more simply, “Treat people how they want to be treated”) coined by Milton Bennett8 has its critics, as some people may wish others to do them harm or may not have the capacity to make appropriate decisions, so there are limits to the universal applicability of care-based thinking.

All the aforementioned approaches to ethics can be discredited with examples of scenarios that fall outside of their paradigms. Rather than focus on the merits or deficits of a specific ethical approach, it is helpful to know that there are multiple ways of approaching ethical dilemmas, as specific situations may require the consideration of a variety of solutions before a decision can be made.

PROFESSIONAL ETHICAL CODES

Having a clearly defined ethical code is a hallmark of a true profession.9 In the library and information science profession, there are several ethical codes that correspond with specialties within the profession. The Code of Ethics of the American Library Association (ALA), the earliest professional code for information professionals, was first adopted in 1939 and establishes broad principles to “guide the work of librarians [and] other professionals providing information services.”10 The Code of Ethics for Archivists from the Society of American Archivists (SAA) and the Code of Ethical Business Practice from the Association of Independent Information Professionals (AIIP) cover many of the same topics, but also address issues that are unique to their respective situations.11 A relative newcomer on the scene, the IFLA Code of Ethics for Librarians and Other Information Workers from the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) was first adopted in 2012 and is the most detailed of these four examples, as it must establish some principles that are taken for granted in individual countries.12 While these statements cannot provide guidance in every situation, they serve as reminders of the principles that are the foundation of the information profession. See textbox 30.1.

TEXTBOX 30.1

Professional Codes of Ethics

• Code of Ethics of the American Library Association: http://www.ala.org/tools/ethics

• Code of Ethics for Archivists from the Society of American Archivists: http://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics

• Code of Ethical Business Practice from the Association of Independent Information Professionals: http://aiip.org/About/Professional-Standards

• IFLA Code of Ethics for Librarians and Other Information Workers: http://www.ifla.org/news/ifla-code-of-ethics-for-librarians-and-other-information-workers-full-version

The Profession’s Shared Principles

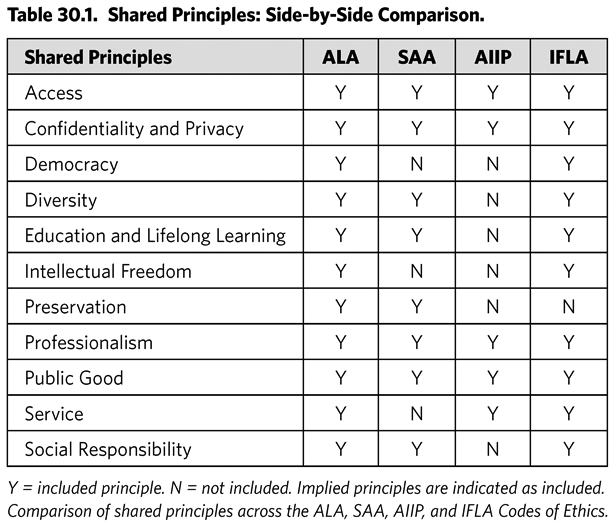

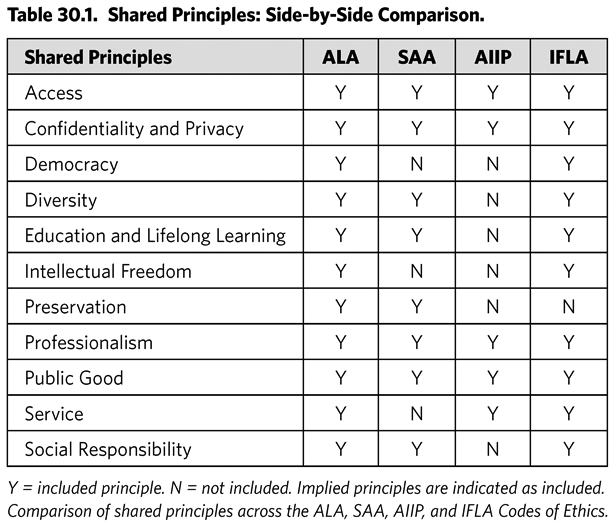

When faced with an ethical dilemma, one of the first steps is to determine what principles are in conflict. In a professional setting, it is imperative for shared principles to be identified and articulated. Of the four professional codes mentioned previously, only the SAA Code of Ethics for Archivists is explicitly paired and presented with a statement of core values: the SAA Core Values of Archivists.13 This statement is essential to understanding the full commitment of archivists to their principles. Though not presented in tandem with the ALA Code of Ethics, the ALA Core Values of Librarianship statement is a good starting point for a broad list of shared principles and is used as the framework for comparing how these principles are represented in the four ethical codes.14 Table 30.1 presents these comparisons in a side-by-side format with detailed comparisons following.

Access

ALA mentions equitable access in the very first article, denoting its importance among principles.15 Likewise, the first section of the IFLA code is titled “Access to Information” and details why access is so important.16 “Access and Use” is an entire section within the SAA code and includes an acknowledgment that access may be restricted due to donor agreements based on protecting confidential information, thus highlighting how competing principles may sometimes cause an ethical dilemma.17 Though access does not necessarily apply to the client of an independent information professional, AIIP’s code includes “giv[ing] clients the most current and accurate information,” which is similar to ensuring good access to information18 (see also chapter 15: “Accessing Information Anywhere and Anytime: Access Services”).

Confidentiality/Privacy

All four codes reference confidentiality and privacy for users regarding information use.19 As it did with access, the SAA code spells out special responsibilities for both donor and user privacy (see also chapter 34: “Information Privacy and Cybersecurity”).

Democracy

Alone among the codes, the preamble to the ALA code notes that information professionals are in a “political system grounded in an informed citizenry” and states that the profession has a “special obligation to ensure the free flow of information.”20 Given the specialized roles of archivists and independent information professionals, and given that democracy is not the only form of government in countries represented by IFLA, the absence of a specific mention in the other three codes is not a surprise. It is worth noting that the SAA Core Values of Archivists statement does make a clear reference to the relationship between democracy and archives when they document “institutional functions, activities, and decision-making” for purposes of accountability.21

Diversity

The IFLA code has the only explicit reference to diversity, noting “that equitable services are provided for everyone whatever their age, citizenship, political belief, physical or mental ability, gender identity, heritage, education, income, immigration and asylum-seeking status, marital status, origin, race, religion or sexual orientation”22 (see also chapter 5: “Diversity, Equity of Access, and Social Justice”). The IFLA code also calls for respect for language minorities. Though the SAA code’s preamble states that archives “provide evidence of the full range of human experience” and the ALA code mentions serving “all library users,” these references to diversity are implicit at best.23 However, the SAA core values statement includes an entire section on diversity.24 The AIIP code does not address diversity.

Education and Lifelong Learning

Article VIII of the ALA Code notes the importance of continuing education for members of the profession.25 IFLA includes education as one of the core missions of libraries and specifically mentions increasing reading skills and teaching information literacy and also notes the importance of professional development.26 Though the SAA code does not mention education and lifelong learning, it is part of the SAA core values statement27 (see also chapter 16: “Teaching Users: Information and Technology Instruction”).

Intellectual Freedom

The ALA code specifically states, “We uphold the principles of intellectual freedom,” while the IFLA code references the importance of “freedom of opinion, expression and access to information”28 (see also chapter 35: “Intellectual Freedom”). Neither the SAA code nor its core values statement makes explicit reference to intellectual freedom, though elements of intellectual freedom such as privacy and access have been noted above. The AIIP code does not mention intellectual freedom.

Preservation

Not surprisingly, multiple sections of the SAA code and core values statement refer to the importance of preservation29 (see also chapter 13: “Analog and Digital Curation and Preservation”). The ALA code implies that preservation is a responsibility in its preamble when it states that librarians have “a special obligation to ensure the free flow of information and ideas to present and future generations.”30 While the need to publicize preservation policies is mentioned in the IFLA code’s section on neutrality and professionalism, the purpose of preservation is not discussed.31 The AIIP code does not include preservation.

Professionalism

All codes include professionalism as a concept. ALA, SAA, and IFLA all call for fairness and respect when dealing with other members of the profession, while AIIP gives clear direction about respecting the rules of libraries, not accepting projects that would be “detrimental” to the profession, and upholding the profession’s reputation.32 The SAA core values statement also includes a section on professionalism.33

The Public Good

This core value may not be easily understood without some context. The ALA core values statement affirms that “libraries are an essential public good” in light of movements to outsource and/or privatize library services.34 In this sense, none of the codes address this value beyond previous mentions of connections to democracy. The SAA core values statement does explicitly mention the public good with reference to social responsibility, but in the context that archives have a responsibility to the public good, not that archives are a public good.35

Service

All codes except SAA highlight service as a primary value of the profession, though SAA’s core value statement does include a section devoted to service.36

Social Responsibility

Like the concept of the public good, this concept may benefit from context. The ALA core values statement says that “The broad social responsibilities of the American Library Association are defined in terms of the contribution that librarianship can make in ameliorating or solving the critical problems of society.”37 The IFLA code is the only one that specifically mentions social responsibility as inherent to the profession because of the importance of information service to “social, cultural and economic well-being.”38 The SAA core values statement includes a section on social responsibility, explaining that archivists are responsible not only to their employers and institutions but also to the greater society because of their custody of the cultural record.39

Reflecting on the four professional codes, the choice between brevity and detail can make a big difference in what principles or values are clearly stated and what needs to be inferred. IFLA, with the longest code at almost 1,600 words, has the most inclusive approach when it comes to explicating shared principles. The choice to pair an ethical code (of just over 800 words) with a core values statement (of just over 1,400 words) allowed SAA to have a shorter code, though some of those core values were not reflected in that shorter code. That some issues were still not covered in the combined statement shows that a specialized professional statement can get into great detail on matters of special concern while still ignoring areas of broader concern. The AIIP code shows a very different approach to a specialized statement. At 187 words, it is the shortest of the four and is focused exclusively on the concerns of this subset of the profession. Finally, the ALA code favors brevity over detail at 380 words. Twelve of those words were added in the latest revision to expand upon an issue not previously discussed in this chapter, as this topic (intellectual property) was not included in either of the core values statements. Yet, three of the four codes (ALA, IFLA, and AIIP) state that information professionals should respect intellectual property, and ALA and IFLA go on to discuss the rights of information users (IFLA, of course, in much greater detail).40 This is an example of how codes of ethics may sometimes include principles of how information professionals ought to act regarding a topic that may not be at the spiritual heart of a profession but nevertheless is vital to the profession’s work. It is also an example of how ethical codes can adjust and change in response to current trends.

Discussion Questions

The principal, in response to a parent’s complaint about a book in the school library, removes the book and puts it in her office without following the official policy for handling challenges. Do you say anything? If so, what and to whom?

KEEPING PACE WITH A CHANGING WORLD

As noted earlier, the ALA Code of Ethics was first created in 1939. Though it has been revised three times since its adoption to address necessary changes, is it possible that some of the values are no longer relevant? In other words, do print-based principles apply to a digital world? The short answer is yes, but not without recognizing how the world has changed or explaining why the principles are still relevant.

Digital Content

Information organizations continue to shift their collections from print/analog to digital content. While some library users provide their own devices for accessing the content, there will always be some people who need to use or borrow library-provided devices, as they do not have anything suitable (or at all). It may be technically equal access to say that everyone has the same right to download content, but the professional ethical codes call for equitable access, which means that information professionals need to bridge the gaps created by individual needs. Whether those needs take the form of equipment, skills deficits, or other barriers to accessing content, information professionals must do their best to remove those barriers. At the same time, if information organizations spend too much money on devices, they will have less money for increasingly expensive content. Meanwhile, licensing continues to supplant purchasing as the model for acquiring content, especially when it is in digital form. If information professionals leave behind the limits on copyright that allowed their organizations to lend and reproduce portions of purchased content, how are they ensuring the free flow of information to future generations?

Diversity

A 2012 study of diversity in the library profession showed a 1 percent increase (from 11 percent to 12 percent) of ethnic and racial minorities working as degreed librarians. In response, ALA president Maureen Sullivan observed that, “Although the findings show some improvement in the diversity of the library workforce, [the profession] clearly has a long way to go. . . . To continue to serve the nation’s increasingly diverse communities . . . libraries and the profession must reflect this diversity.”41 Is the profession actively recruiting underrepresented people? Can users truly feel they are receiving the highest level of library service when no one speaks their language or if they cannot find materials that are relevant to their communities? Is digital content accessible to those using adaptive equipment? If diversity is one of the profession’s shared principles, then it is imperative the information professional move beyond statements of openness and learn how to live it. The adoption of equity, diversity, and inclusion as a fourth strategic direction of the ALA42 is a promising development and may signal a commitment to action, but it is still too early as of this writing to judge the success of this initiative.

Internet Filtering

Since the upholding of the Children’s Internet Protection Act43 in 2003, the use of internet filters in public (see also chapter 8: “Community Anchors for Lifelong Learning: Public Libraries”) and school libraries (see also chapter 6: “Literacy and Media Centers: School Libraries”) has become ubiquitous. A recent study by the ALA reveals a tendency for information organizations to over-block content beyond what is required by law and that the use of internet filters has a disproportionate impact on access to information for those library users without internet access at home.44 Additionally, filters continue to be imperfect, blocking appropriate content and letting other materials through, so there are still concerns about censorship. How do information professionals balance the desire to save money through the e-rate discounts that come with adopting a filter with the ethical imperative to ensure equitable and unfettered access to information?

User-Created Content

Information organizations have become places where users interact with and create content, rather than just consume it (see also chapter 18: “Creation Culture and Makerspaces”). If information organizations allow users to add their own reviews and comments to library materials in the catalog or through library social media outlets, is it censorship to remove a racist or sexist remark? At what point do organizations place limits on the use of 3-D printers and other makerspace equipment? When does someone’s hobby turn into a library-supported business? What obligations do information professionals have to educate users about the copyright implications of their latest video mashup made on library equipment?

Privacy

Many pundits have stated that privacy is dead, and the continuing convergence of online services and resources makes it increasingly difficult to maintain a private persona without opting out of the online world completely. Social media allows individuals to broadcast and document the minutiae of their lives, and many do so voluntarily. Yet, the profession still invests significant resources and political capital in the public defense of privacy, and the public outcry over revelations of the National Security Agency’s data collection practices demonstrates that not everyone undervalues privacy. Is it right for ALA to continue to invest in educational efforts like Choose Privacy Week45 when its resources are stretched thin? Is it right to abandon a principle that has been enshrined in the Code of Ethics since its inception?

Check This Out

Choose Privacy Week. Visit: www.chooseprivacyweek.org.

Service Models

The first article of the ALA Code of Ethics states: “We provide the highest level of service to all library users through . . . equitable service policies [and] equitable access.”46 The term “service” can be looked at in several ways. A move toward self-service has freed up staff to work on other projects. Some users might like the increased sense of privacy that comes with using a self-check machine, while others are concerned that their materials on open hold shelves are identified with their names for all to see (see also chapter 14: “User Experience”). Information organizations of all types have seen an increase in online users, including those who never step foot in a physical library. Do online users get the same level of service as walk-up users? Alternatively, if information professionals move away from the traditional reference desk to a more centralized service center, are they offering the highest level of service to the technology-averse user encouraged to “live chat” with their reference questions? How do information organizations strike a balance between supporting traditional services and testing innovative ideas? How do information professionals evaluate services and programs when funding is tight and cuts must be made?

Discussion Question

A vendor recently changed its platform to restrict printing of documents to one page at a time. You discover a work-around that restores the ability to print in larger quantities. Do you share this information with your colleagues? Your users? The vendor?

Neutrality

Article VII of the ALA Code of Ethics states, “We distinguish between our personal convictions and professional duties and do not allow our personal beliefs to interfere with fair representation of the aims of our institutions or the provision of access to their information resources.”47 This has often been interpreted to mean that information professionals must be neutral and cannot take positions on any issue. However, while the profession has aimed to be neutral about what is included in the content of collections, the profession has not been neutral about who should be able to access the content of those collections. In an increasingly divided political climate, some information professionals have called for restricting hate speech in their institutions, whether that means placing restrictions on user conduct or removing (or not adding) materials deemed to be hateful to others. When does selection turn into censorship? How can an organization support equity, diversity, and inclusion while keeping or adding materials that contradict those values? Should racists or any other group promoting hatred feel welcome at the library?

For all of these trends, there is a common theme: rather than finding answers, more questions arise. This is usually the case with ethical dilemmas. As noted in the preamble of the ALA Code of Ethics, the “principles of this Code are expressed in broad statements to guide ethical decision making. These statements provide a framework; they cannot and do not dictate conduct to cover particular situations.”48 Therefore, being comfortable with the profession’s ethical principles is important to good decision making, as is knowing when to seek assistance.

GETTING HELP

Ethical dilemmas are by nature difficult to resolve—if it is easy to resolve, it is not truly a dilemma. There are resources from ALA that can help. The Office for Intellectual Freedom offers assistance to the library profession when dealing with ethical challenges and other issues related to core principles. The ALA Committee on Professional Ethics provides guidance on ethical issues through interpretative statements of the ALA Code of Ethics in a question-and-answer format, covering such topics as social media, conflicts of interest, and workplace speech, and in 2014 issued the first-ever interpretation of the Code of Ethics on copyright.

The best strategy for resolving ethical dilemmas is preparation. All information professionals should be aware of policies and procedures at their institutions, and regular reviews of policies and procedures serve as both a refresher on content and an opportunity to address new developments. Since professional values should be at the heart of these policies and procedures (e.g., access, privacy, balancing copyright and fair use), openly discussing these issues can educate new staff as well as remind others about what is truly important. In addition to knowing policies and procedures, an effective training method for resolving ethical dilemmas is by using scenarios. Participants are given a scenario that poses an ethical dilemma and are asked to discuss all the issues before deciding on what they would do. In addition, manag ers should keep track of issues happening in the workplace and discuss them at regular staff meetings to evaluate what was done well and what could have been done differently. It does not have to be a life-or-death situation to be good practice of how to resolve a dilemma.

Check This Out

The Office for Intellectual Freedom and the ALA Committee on Professional Ethics provides guidance on ethical issues through interpretative statements of the ALA Code of Ethics. Visit: http://www.ala.org/oif.

THINKING AHEAD

As the challenges facing information professionals continue to change and evolve, it is essential to stay on top of the latest news, updates, and resources so that actions can be forward thinking and not just reactive. There are many ways that information professionals can be proactive in the ethical realm:

• Join a professional organization (local, state, regional, national, international) and get involved, as active participation provides opportunities to learn about the latest trends facing the information professions through committee work and networking.

• Attend professional conferences, webinars, and other educational opportunities to stay current in the field and discover how colleagues are addressing shared concerns. Likewise, read blogs, articles, and books to continue learning in an informal setting.

Check This Out

The Intellectual Freedom Committee of the Colorado Association of Libraries has developed many scenarios that are freely available through their website, along with other training materials. Visit: www.cal-webs.org/?page=IFCTraining.

• Subscribe to updates from organizations devoted to job-related issues, such as the ALA Washington Office Newsline49 for the latest on government policies and legislative initiatives or the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom’s Intellectual Freedom News50 for news on censorship, privacy, and information access.

• Develop and use professional networks for regular conversations about ethical concerns and to learn from each other’s experiences.

By staying connected and current, information professionals will be better prepared to fight for their communities’ right to access information and to address ethical issues as they arise.

CONCLUSION

Change is a constant in the library and information science profession (see also chapter 20: “Change Management”). Information organizations are constantly adapting to new technologies, new demands on services, and new opportunities for serving their communities. At the same time, tradition plays an important part in what the profession represents. Collections represent the cultural heritage of society, and many information organizations have been at the heart of their communities for time immemorial. Along with the need to balance the competing needs of change and tradition comes the need to balance the competing interests of the latest ethical dilemma. Ethical codes serve as a reminder of the industry’s principles, but the intentional lack of specificity requires information professionals to think before applying these principles to current situations. Reviewing past challenges and current issues demonstrates that there have been ample opportunities to apply ethical principles, and the future will surely bring new and unpredicted controversies. Information professionals can, however, depend upon these principles to remain applicable to whatever comes their way, provided they face each ethical dilemma as it comes and not rely on past practice to supply the only answer.

NOTES

1. Edwin M. Elrod and Martha M. Smith, s.v. “Information Ethics,” in Encyclopedia of Science, Technology, and Ethics (Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005).

2. Henry R. West, “J. S. Mill,” in The Oxford Handbook of the History of Ethics, ed. Roger Crisp (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), doi:0.1093/oxfordhb/9780199545971.013.0025.

3. John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism (London: Parker, Son, and Bourne, 1863).

4. “Immanuel Kant Biography,” Who2Biographies, accessed August 12, 2017, http://www.who2.com/bio/immanuel-kant/.

5. Andrews Reath, “Kant’s Moral Philosophy,” in The Oxford Handbook on the History of Ethics, ed. Roger Crisp (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199545971.013.0021.

6. Andrew H. Plaks, “Golden Rule,” in Encyclopedia of Religion (Detroit, MI: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005).

7. Virginia Held, “The Ethics of Care,” in The Oxford Handbook of Ethical Theory, ed. David Copp (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195325911.003.0020.

8. Milton J. Bennett, Basic Concepts of Intercultural Communication: Selected Readings (Yarmouth, ME: Inter-cultural Press, 1998), 212–13.

9. Kenneth McLeish, ed., “Profession,” in Bloomsbury Guide to Human Thought (London, UK: Bloomsbury, 1993).

10. “Code of Ethics of the American Library Association,” American Library Association, last modified January 22, 2008, http://www.ala.org/tools/ethics.

11. “Code of Ethics for Archivists,” Society of American Archivists, last modified January 2012, http://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics; “Code of Ethical Business Practice,” Association of Independent Information Professionals, last modified April 20, 2002, http://aiip.org/About/Professional-Standards.

12. “IFLA Code of Ethics for Librarians and Other Information Workers,” International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions, last modified August 2012, http://www.ifla.org/news/ifla-code-of-ethics-for-librarians-and-other-information-workers-full-version.

13. “Core Values of Archivists,” Society of American Archivists, last modified May 2011, http://www2.archivists.org/statements/saa-core-values-statement-and-code-of-ethics.

14. “Core Values of Librarianship,” American Library Association, last modified June 29, 2004, http://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/corevalues.

15. “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” art. I.

16. “IFLA Code of Ethics,” art. 1.

17. “Code of Ethics for Archivists,” Access and Use.

18. “Code of Ethical Business Practice.”

19. “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” art. III; “IFLA Code of Ethics,” art. 3; “Code of Ethics for Archivists,” Privacy; “Code of Ethical Business Practice.”

20. “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” preamble.

21. “Code of Ethics for Archivists,” preamble.

22. “IFLA Code of Ethics,” art. 2.

23. “Code of Ethics for Archivists,” preamble; “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” art. I.

24. “Core Values of Archivists,” Diversity.

25. “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” art. VIII.

26. “IFLA Code of Ethics,” arts. 1, 2, and 5.

27. “Core Values of Archivists,” Professionalism.

28. “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” art. II; “IFLA Code of Ethics,” preamble.

29. “Code of Ethics for Archivists”; “Core Values for Archivists.”

30. “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” preamble.

31. “IFLA Code of Ethics,” art. 5.

32. “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” art. V; “IFLA Code of Ethics,” art. 6; “Code of Ethics for Archivists,” Professional Relationships; “Code of Ethical Business Practice.”

33. “Core Values of Archivists,” Professionalism.

34. “Core Values of Librarianship,” The Public Good.

35. “Core Values of Archivists,” Social Responsibility.

36. “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” art. I; “IFLA Code of Ethics,” preamble, arts. 1, 2, and 5; “Code of Ethical Business Practice”; “Core Values of Archivists,” Service.

37. “Core Values of Librarianship,” Social Responsibility.

38. “IFLA Code of Ethics,” preamble.

39. “Core Values of Archivists,” Social Responsibility.

40. “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” art. IV; “IFLA Code of Ethics,” art. 4; “Code of Ethical Business Practice.”

41. “Diversity Counts,” American Library Association, accessed August 1, 2017, http://www.ala.org/offices/diversity/diversitycounts/divcounts.

42. “About ALA,” American Library Association, accessed August 1, 2017, http://www.ala.org/aboutala/.

43. “The Children’s Internet Protection Act (CIPA),” American Library Association, accessed August 12, 2017.

44. Kristen R. Batch, “Fencing Out Knowledge: Impacts of the Children’s Internet Protection Act 10 Years Later,” American Library Association, last modified June 2014, http://connect.ala.org/files/cipa_report.pdf.

45. “Choose Privacy Week,” American Library Association, accessed August 1, 2017, https://chooseprivacyweek.org.

46. “Code of Ethics of the ALA,” art. I.

47. Ibid., art. VII.

48. Ibid., preamble.

49. “#ALAWO Newsline,” American Library Association, accessed August 1, 2017, http://ala.informz.net/ala/pages/ALAWON.

50. “Intellectual Freedom News,” American Library Association, accessed August 1, 2017, http://ala.informz.net/ala/profile.asp?fid=3430.