KOOPMANS-DE WET HOUSE

Strand Street

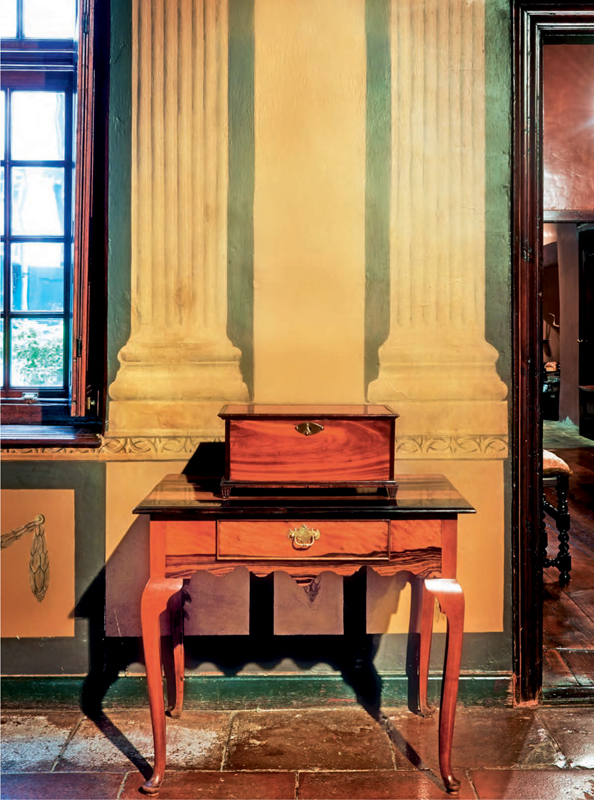

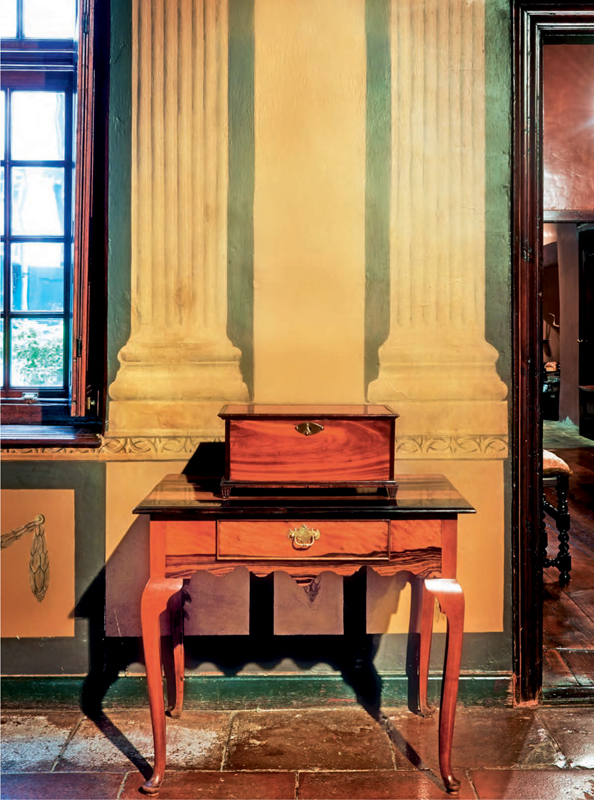

In the gaanderij, or lower hall, the neoclassical wall decoration behind the Cape coromandel side table (c.1780) is original – first uncovered around 1913 by Dr William Purcell, whose aim was to restore the house to its original 18th-century appearance.

The fact that this house survives at all is something to celebrate. Once at the seafront, Sea Street, now Strand Street, was lined with dwellings of considerable architectural merit and this was one of them.

Neoclassicism emerged in the Cape in the 1780s, probably following the lead of French-born architect Louis Michel Thibault. Some of the finest townhouses of the period were built at this time; Koopmans-de Wet is one of the very few to have survived comparatively unaltered. Maybe Thibault’s work, maybe not, the façade is perfectly classical: four fluted pilasters support a heavy cornice, the inner two a pediment, and beautiful fenestration is symmetrical about a pilastered door case mounted on a raised stoep made out of pretty little Dutch klinker bricks and Robben Island slate.

Marie Koopmans-de Wet inherited the house from her father, whose family had owned it since 1806. She was a society hostess, and many of the leading political and cultural figures of the day were entertained here. But she’s remembered for having worked untiringly for the preservation of South African antiques and historic buildings long before any conservation body was established. She helped save the derelict Castle from partial demolition to make way for the new railway, and was instrumental in preserving Groot Constantia. By 1905, for many white Capetonians, English and Afrikaans, a South African identity was interwoven with a pride in a neglected Cape heritage, the rediscovery of which resulted in the preservation of some of its oldest structures. This is the context to Koopmans-de Wet House’s own survival. A few years after Mrs Koopmansde Wet’s death in 1906, the house and its contents became a museum.

Where else in the old city can you examine the interior of an 18th-century mansion retaining not only its original layout and decoration, but replete with an assortment of furnishings, porcelain, textiles and paintings that you might have found in the 1770s in Cape Town, ‘that great inn, on the highway to the east,’ said Charles Darwin. The nucleus of its collection was bequeathed by Mrs Koopmans-de Wet.

But, perhaps most poignantly in the context of modern South Africa, the origins of the divisions between white and non-white are nowhere clearer than at Koopmans-de Wet House. The psychology of division began in houses like this: the white burghers with their dark-skinned slaves; the superiority of the one, the enforced subservience of the other; the illicit liaisons and the half-breed offspring. People aren’t really aware of how everybody was put together all those years ago, and we live with the results now. And when those slaves were emancipated, the stereotypes didn’t just vanish. Places like this built this nation. Life inside Koopmans-de Wet House was a microcosm of the world outside. And it’s all the more poignant here because, while conscious efforts have been made to preserve the domestic context of prosperous 18th-century gentry, unwittingly the life of the slaves with whom they co-existed has been preserved too – although you need a far richer imagination to bring that to life.

Amongst the more tangible legacies is a vernacular urban building style that was adapted to prevent arson by rebelling slaves: the removal of thatch from roofs and wooden shutters from façades; the integration of exterior lighting with door cases to lighten the streets at night; and water channels in front of many of the homes to provide water in case of fire. And in the kitchen, what language were the slaves using, and what were they cooking? Here the so-called ‘kitchen Dutch’, evolving on ships amongst seafarers of Dutch, Portuguese and Indonesian origin, emerged, a sort of lingua franca amongst domestic slaves known as ‘Afrikaaps’ – eventually to become Afrikaans. And the food from kitchens such as this is at the core of what would one day give South African cuisine its peculiar character and originality. Here, at houses like this, it all began.

The dining room, a formal room at the front of the house, is furnished with a mixture of pieces. The dining table is English Regency (1810–1820), while the display cupboard containing Cape and Dutch silver is Cape (1775–1800). On the table is part of a late 18th-century Chinese dinner service. The windows look onto Strand Street.

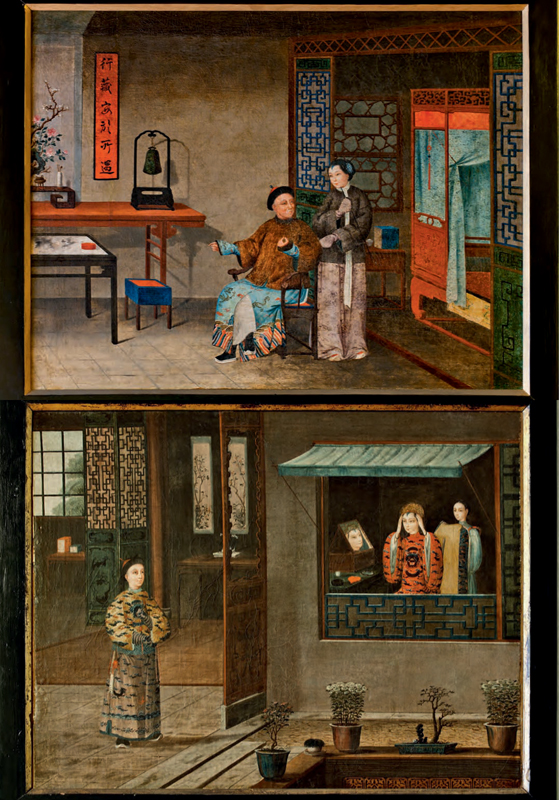

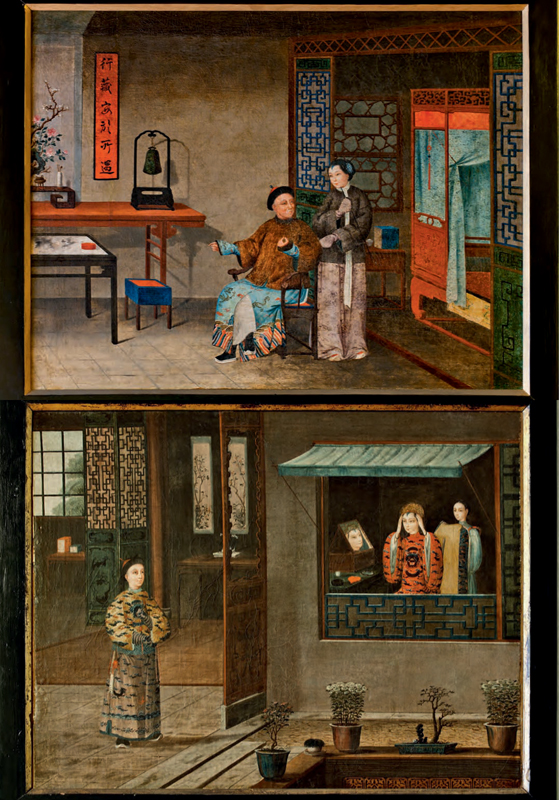

Chinese export art painted in the so-called Jesuit tradition (c.1820). Two paintings hang in the dining room, and two in the drawing room opposite.

The windows in the gaanderij, or lower hall. From here, the mistress of the house could keep an eye on her slaves’ activities in the kitchen courtyard.

From her vantage point in the gaanderij, with its view onto the front door, the stair and the kitchen, as well as the doors to all the other rooms, the mistress was able to supervise the household activities and see who was coming and going. Both the gate-leg table, made of Burmese teak and stinkwood (c.1750), and the Queen Anne-style stinkwood settee (c.1770) are Cape.

A detail of the trompe l’oeil fire surround in the music room. The faux marble is bordered by ‘wooden’ mouldings and adorned with ‘applied’ gesso detail. The wall decorations in this house are an exceptional survival.

A collection of landscape paintings hangs in the morning room. Thought to be Italian, they date from the late 18th century.