LODGE DE GOEDE HOOP

Stal Plein

Looking east to the Master’s chair, a large part of this chamber, the Temple, was destroyed by fire in the 19th century and rebuilt. Cut into the barrel-vaulted ceiling is the Firmament. Before the fire, four larger-than-life-size statues by sculptor Anton Anreith stood against the flanking walls.

Just to the left of the Tuynhuis, on the edge of the Company’s Garden and behind a huge, antique tree, there’s a glimpse of it. Mostly out of sight, you’d never know it was there. It’s on the other side of the Stal Plein gate, Louis Thibault’s extraordinarily simple, whitewashed ‘triumphal arch’ that hides what was once a garden, in the middle of which stands the old Fountain of Hope. Like the Lodge itself, hidden from view and out of sight, you’d never know it was there unless you’d set out to look for it. Completed in 1803, the Lodge de Goede Hoop, a Masonic temple, is the work of the three greats of early 19th-century building in Cape Town: Louis Thibault, Anton Anreith and Hermann Schutte, respectively architect, sculptor and builder – all of them Freemasons. Unusual, eccentric, odd – these are all words that have been used to describe the Lodge’s appearance. In fact, it’s a harmonious display of geometric shapes rising upwards and spreading outwards, the severity of its inherent neo-Classicism skewed only by latent Mannerist madness characterized by a stylish ingenuity.

Within, the walls of a handsome octagonal foyer are faced with Coade stone blocks, and there’s a niche in each corner. This simple, striking chamber leads to the Robing Room, where two sets of 12-foot double doors, flanked with perfect symmetry by an apse on either side and two pairs of decorative columns, are on axis with the main entrance. Opened, these massive doors reveal the barrel-vaulted Temple Chamber itself, a black-and-white paved rectangle whose dimensions are reputedly based on those of the inner sanctum of King Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem. At the far end of it, on axis with the entrance, is the Master’s throne. Placed at intervals along its walls are four late 19th-century statues depicting Wisdom (a copy of the Giustiniani Minerva, the original of which is in the Vatican), Strength (a copy of the Lansdowne Hercules), Beauty (a copy of the tinted Venus by John Gibson) and Hope (which was a local creation). These statues were put in place in the late 1890s to replace four by Anreith that, along with much of this chamber, were destroyed by a fire in 1892.

But there’s more, and this time it’s the real thing. To the left of the foyer is the Preparator’s Room with stairs up to the organ loft. Continue going, and you enter the Chamber of Meditation from which, further into the depths of the building, a low, sloping corridor leads to the Middle Chamber. While the Chamber of Meditation is dark, with Anreith’s life-size sculpture of Hiram Abiff lying dead in a niche, the Middle Chamber is completely black. Gothic tracery, gilded and marbled, adorns the walls. It’s like something out of an early Gothic novel – Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto springs to mind. In a little chapel at the far end is the statue of Bereavement, in which a mother laments her dead son, also by Anreith.

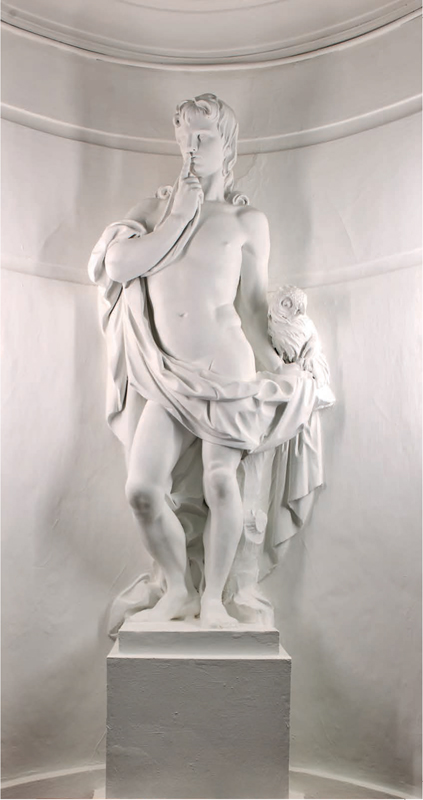

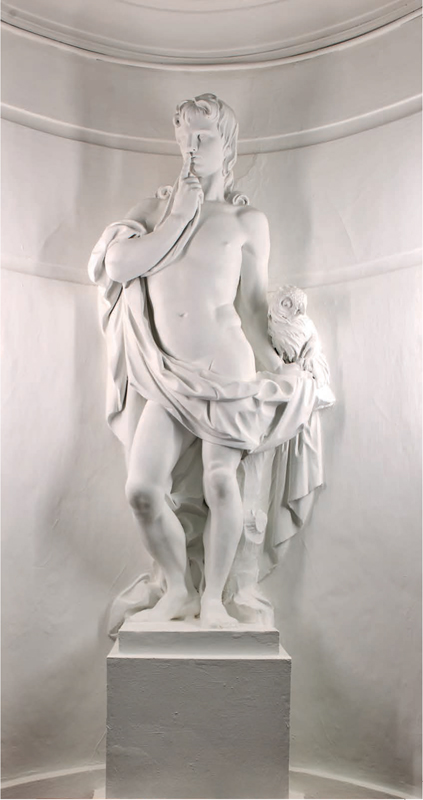

On the foyer’s right, an anteroom leads to the Chamber of Silence, in which a small table and chair for contemplation are placed in front of Anreith’s massive figure of Silence, his finger to his lips, an owl on his left arm, revealed if you lift the curtain concealing it.

The Robing Room is the anteroom separating the entrance foyer and the Temple. Here, members of the Lodge change into their ceremonial regalia.

Through the portal of the Temple, with its neo-Classical plasterwork, a rigid sightline connects with the front door.

The Chamber of Meditation, a portion of the Lodge undisturbed by the fire and therefore entirely original, houses Anton Anreith’s lime plaster figure of Hiram Abiff, seen through the low passageway that links it with the Middle Chamber.

Hiram Abiff in Death, one of the three statues by Anreith to have survived the 1892 fire at the Lodge, and largely unknown to a public well aware of the sculptor’s other extant work at the Groote Kerk, the Evangelical Lutheran Church, and elsewhere in Cape Town.

The Middle Chamber, viewed from the passageway linking it to the Temple itself.

The Chamber of Silence houses Anreith’s Silence, his finger to his lips. Filled with symbolism, as are the other sculptures at the Lodge, here the owl on his arm signifies watchfulness.

One of the most extraordinary rooms in Cape Town (1802), the Middle Chamber, with its dark paint and Gothic detail, is entirely original. In the chapel at the east end is Anton Anreith’s striking Bereavement, in which a widow laments the death of her son.