In the early 10th–14th centuries, before the consolidation of the Siamese kingdom, the peninsula was a confluence of diverse cultural and religious influences fought over by local warlords and a vassal state to regional powerhouses.

In the beginning

The earliest known civilisation in Thailand dates from around 3600 BC, when the people of Ban Chiang in the northeast developed bronze tools, fired pottery and began to cultivate rice. The Tai people, after whom the kingdom is named, did not even inhabit the region of present-day Thailand during this time, but are thought to have been living in loosely organised groups in what is now southern China.

An artist’s impression of Bangkok in 1846.

Mary Evans Picture Library

Little is known of the history of Thailand’s coastal regions until around two millennia ago, by which time it seems certain that Malay peoples had settled in southern peninsular Thailand, along both the Andaman Sea and Gulf of Thailand coasts. Inland, in the wild hills and jungles of the central spine, small groups of Negrito hunter-gatherers eked out a precarious living. Further to the north, Mon people had settled the Tenasserim region and the southern Chao Phraya valley, while further east the Khmers had settled along the southeastern Gulf Coast and in the Mekong delta. Of the Tais, still living far to the north, there was as yet no sign.

The first civilisations to develop on Thailand’s coasts and islands were not Tai, but Malay, Mon and Khmer, each shaped by the advanced Indian and Chinese civilisations that came to exercise powerful and distinct influences across Southeast Asia.

Grand Palace mural depicting Thai history in Wat Pho.

iStock

The Golden Land and Srivijaya

As early as 300 BC, the Malay world, including peninsular Thailand, was already being Indianised by visiting traders in search of fragrant woods, pearls and especially gold, leading the Indians to name the region Suvarnabhumi or ‘Golden Land’. By about AD 500, a loosely knit kingdom called Srivijaya had emerged, encompassing the coastal areas of Sumatra, peninsular Malaya and Thailand, as well as parts of Borneo. Maharajas, or kings, ruled its people, who practised both Hinduism and Buddhism and flourished through brisk trade with India and China.

A series of wars with the Javanese from the 10th century weakened Srivijaya, and the power of the Hindu maharajas was undermined in the region by the arrival of Muslim traders and Islam. By the late 13th century, the new Siamese kings of Sukhothai brought much of the Malay Peninsula under their control.

Head Singha mystical lion Dvaravati style 8th–9th Century AD.

Alamy

The Mon kingdom of Dvaravati

At about the same time that Srivijaya dominated the southern part of the Malay Peninsula, the Mon people established themselves as the rulers of the northern part of the peninsula and the Chao Phraya valley. The kingdom of Dvaravati flourished from the 6th to the 11th century, with Nakhon Pathom, U-Thong and Lopburi its major settlements. Much like Srivijaya, Dvaravati was strongly influenced by Indian culture and religion, and the Mon played a central role in the introduction of Buddhism to present-day Thailand and, in particular, the Andaman Coast. It is not clear whether Dvaravati was a single unitary state under the control of a powerful ruler, or a loose confederation of small principalities. By the 12th–13th centuries, the Tais had moved south, conquering Nakhon Pathom and Lopburi and absorbing much of Mon culture, including the Buddhist religion.

The Kingdom of Pattani

The Kingdom of Pattani was formerly a Malay sultanate comprising the present-day provinces of Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat. It became Muslim in the 11th century, but Siamese influence increased until, in the mid-17th century, Pattani became a tributary state of Ayutthaya. It later rebelled against Thai control during the reign of King Rama I, and its ruler, Sultan Muhammad, was killed in battle. Then, a series of attempted rebellions prompted Bangkok to divide Pattani into seven smaller states. Despite a long association with Thailand, the Malays of Pattani were never culturally absorbed into mainstream Thai society, and the area remains fractious even today.

The Khmer empire

As the coastal regions of western Thailand were dominated by Srivijaya and Dvaravati, another major power was asserting its control over what is now eastern Thailand. This was the Khmer empire of Angkor, forerunner of present-day Cambodia.

Strongly influenced by Indian culture, Khmer civilisation reached its zenith under the reign of Suryavarman II (1113–50), during which time the temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia was built. He united the kingdom, conquering Dvaravati and the area further west to the border with the kingdom of Pagan (modern Burma), expanding as far south into the Malay Peninsula as Nakhon Si Thammarat, and dominating the entire coast of the Gulf of Siam.

The next great Khmer ruler was Jayavarman VII (ruled 1181–1219), who defeated the Chams and initiated a series of astonishing building projects. Yet this was to be the last flowering of Khmer independence until modern times, as the Khmer empire fell victim to the emerging power that would later become known as Thailand.

Sukhothai, the first Thai kingdom

Sukhothai was part of the Khmer empire until 1238, when two Tai chieftains seceded and established the first independent Tai kingdom. This event is considered to mark the founding of the modern Thai nation, although other less well-known Tai states, such as Chiang Saen and Lanna in north Thailand were established about the same time. Sukhothai expanded by forming alliances with the other Tai kingdoms. It adopted Theravada Buddhism as the state religion with the help of Sri Lankan monks. Under King Ramkhamhaeng (ruled 1279–98), Sukhothai enjoyed a golden age of prosperity. During his reign, the Thai writing system evolved and the foundations of present-day Thailand were securely established. He expanded his control over the south, as far as the Andaman Sea and Nakhon Si Thammarat on the Gulf Coast, as well as over the Chao Phraya valley and even southeast into what is within the borders of present-day Cambodia.

A bas relief at Angkor depicting King Suryavarman II holding court.

Rex Features

With the creation of the Sukhothai kingdom, a new political structure came into being across mainland Southeast Asia. At the same time, the Thai newcomers, an ethnically Sinitic people, intermarried with the inhabitants of the states they had supplanted and adopted their Indianised culture.

The kingdom of Ayutthaya

The glories of Sukhothai were short-lived, however. In the early 14th century, a rival Thai kingdom began to develop in the lower Chao Phraya valley, not far from present-day Bangkok. In 1350, the ambitious ruler U-Thong moved his capital from Lopburi to a nearby island on the river – a more defensible location – and gave the new city the name Ayutthaya, proclaiming himself King Ramathibodi (ruled 1351–69). He declared Theravada Buddhism the state religion, invited monks from Sri Lanka to help spread the faith, and compiled a legal code, based on the Indian Dharmashastra, which remained in force until the 19th century.

The Sukhothai King Ramkhamhaeng.

Fotolia

Ayutthaya soon eclipsed Sukhothai as the leading Thai polity. By the end of the 14th century, Ayutthaya was the strongest power in Southeast Asia. In the last year of his reign, Ramathibodi seized Angkor in what was the first of many successful Thai assaults on the Khmer capital. Forces were also sent to subdue Sukhothai, and the year after Ramathibodi died, his kingdom was recognised by China’s Hongwu Emperor, of the newly founded Ming dynasty, as Sukhothai’s rightful successor.

During the 15th century, much of Ayutthaya’s energies were directed southwards toward the Malay Peninsula, where its claims of sovereignty over the great trading port of Malacca were contested. The Malay states south of Nakhon Si Thammarat had become Muslim early in the century, and Islam served as a unifying symbol of Malay solidarity against the Thais thereafter. Although Ayutthaya failed to make Malacca a vassal state, it established control over much of the peninsula.

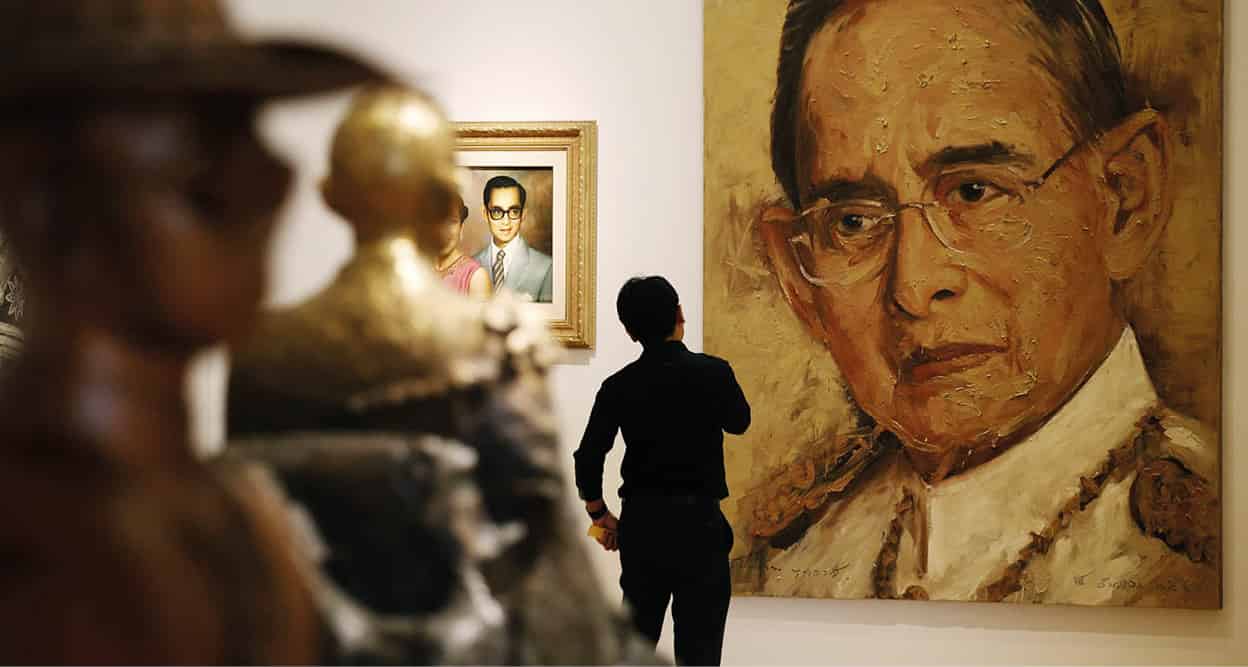

The Monarchy

Since the first independent Thai kingdom was established in 1238, the Thais have been ruled over by kings. To this day, the monarchy is loved by the people.

Although Thailand is officially a constitutional monarchy, an army-led bloodless coup in 1932 having removed the absolute powers of Thailand’s King Prajadhipok, the monarchy remains one of the most influential institutions in the land, and its presence is felt everywhere.

The official representation is seen in the blue bar of the Thai tricolour (red is nation, white is religion); photographs of the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej and his successor Vajiralongkorn adorn government buildings and public spaces; and lese majeste laws carry a penalty of imprisonment for anyone convicted of insulting the royal family.

Radio and TV stations play the national anthem regularly, as do schools, cinemas and railway and bus stations, when people will stand respectfully for the duration.

The king’s subjects have a famed love of his late father and will generally take offence at anyone speaking ill of the monarchy. King Bhumibol’s photograph is frequently found in shops and homes of Buddhists and non-Buddhist minorities alike. In many Muslim homes it is common to find a print of the king next to a picture of the Kaaba at Mecca, as a statement of both spiritual and secular loyalty. There may even be photos of his predecessors hanging alongside, particularly King Mongkut and King Chulalongkorn, the modernisers of Thailand in the late-19th and early 20th centuries.

Books and films about King Mongkut based on The English Governess at the Siamese Court, the memoirs of Anna Leonowens, are all banned in Thailand, including Hollywood favourite The King & I. Leonowens was a tutor of the royal children, but is regarded as having misrepresented her role and life in the palace.

King Bhumibol ascended the throne in 1946 after the mysterious death of his brother King Ananda Mahidol. He died in 2016, having served for over 70 years. It remains to be seen how his successor, King Maha Vajiralongkorn, will be received by the Thai people.

Man of the people

Respect for the king was enhanced by a sense of his morality and representation of traditional Thai values in the face of corrupt governments. He was seen as the ameliorating figure in the conflicts of 1973, 1976 and 1992, when the army and police killed many civilians. In recent years, though, he was criticised by some supporters of Thaksin Shinawatra, who believe elements of the traditional elite were involved in the overthrow of the fugitive ex-prime minister. The lese majeste laws have been used more widely than usual during recent years to silence political rivals of all sides. They will probably continue to be used often as the new king is, thus far, a rather controversial figure.

King Bhumibol was also seen as a man of the people, particularly through his work in the King’s Project, which helped small agricultural communities. His subjects were genuinely proud of his achievements in the field of jazz; he jammed with players Stan Getz and Benny Goodman. Huge crowds would turn out for the king’s birthday celebrations in Sanam Luang each December.

Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra.

Narong Sangnak/EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

The rise of Burma

The 16th century witnessed the rise of Burma, which, under a powerful and aggressive dynasty, waged war on the Thais. In 1569, Burmese forces captured the city of Ayutthaya. King Naresuan the Great (ruled 1590–1605) succeeded in restoring Siamese independence, but in 1767, the Burmese armies once again invaded Ayutthaya, destroying Siam’s capital.

Despite this, Siam made a rapid recovery. A noble of Chinese descent named Taksin led the resistance. From his base at Chanthaburi on the southeast coast, he defeated the Burmese and re-established the Siamese state. Taksin also set up the capital at Thonburi and was crowned king in 1768. He rapidly reunited the central Thai heartlands, and marched south to re-establish Siamese rule over all southern Thailand and the Malay states as far south as Penang and Trengganu.

Although a brilliant military tactician, Taksin was, by 1779, in political trouble. He alienated the Buddhist establishment by claiming to have divine powers, and attacked the economically powerful Chinese merchant class. In 1782, a rebellion broke out, and Taksin was murdered.

The city of Ayutthaya was ruined by the Burmese invasion.

Alamy

The Chakri dynasty of Bangkok

In 1782, General Chakri assumed the throne and took the title Phra Phutthayotfa (King Rama I). One of his first decisions was to move the capital across the Chao Phraya River from Thonburi to the small settlement of Bang Makok, the ‘place of olive plums’, which would become the city of Bangkok. His new palace was located on Rattanakosin Island, protected from attack by the river to the west and by a series of canals to the north, east and south. Rama I restored much of the social and political system of Ayutthaya, promulgating new law codes, reinstating court ceremonies and imposing discipline on the Buddhist monkhood. Six great ministries headed by royal princes administered the government, one of which – the Kalahom – controlled the south.

In 1785, underestimating the resilience and strength of the new king, the Burmese once again invaded, driving far to the south to attack Phuket, Chaiya and Phattalung before being defeated by Rama I near Kanchanaburi. By the time of his death in 1809, Rama I controlled the Malay Peninsula as far south as Kedah and Trengganu, as well as the Gulf Coast as far east as the Cambodian frontier with Vietnam. Siam had become an empire considerably larger than Thailand today.

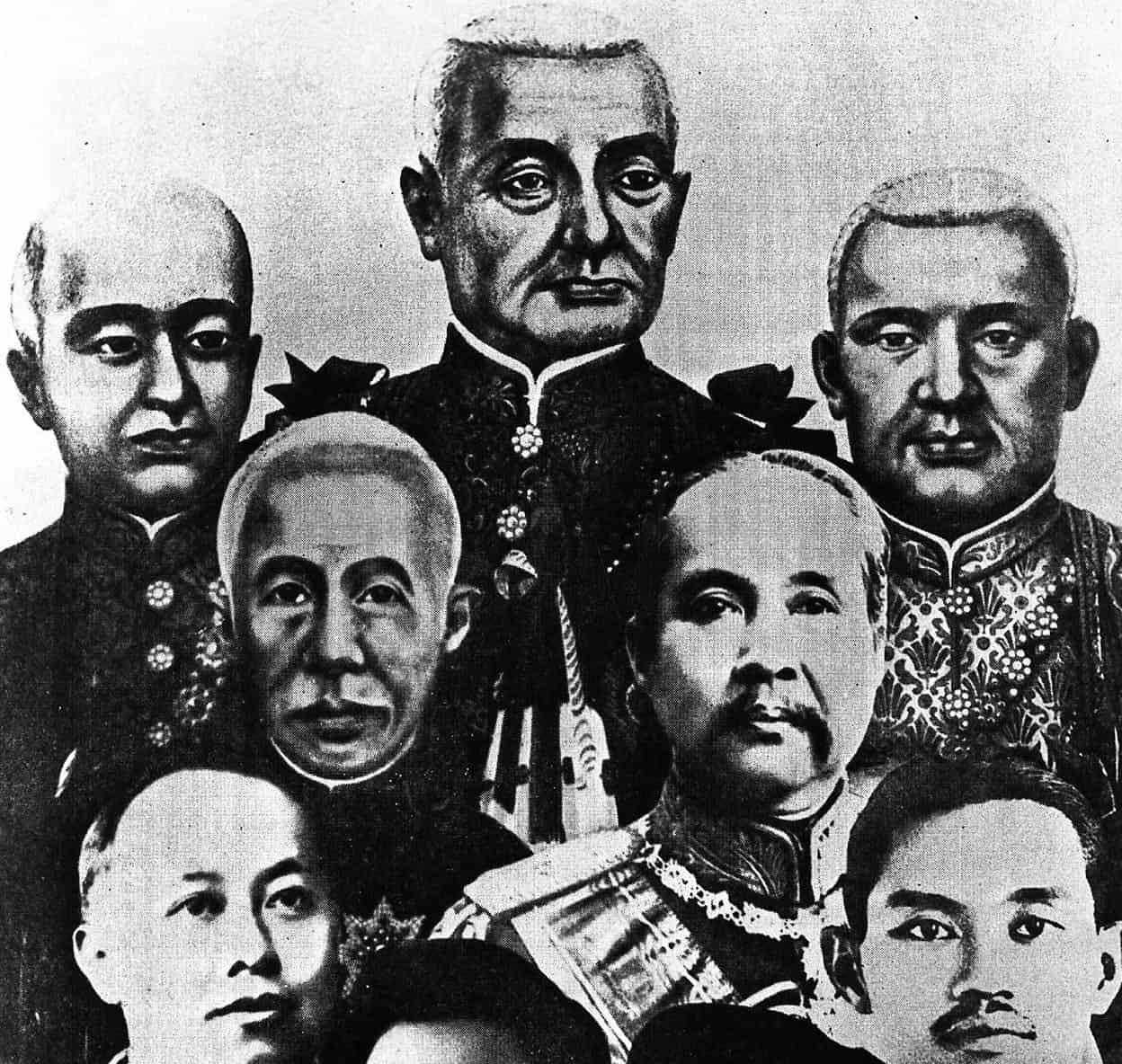

Chakri monarchs in order of reign (left to right, from top), kings Mongkut (Rama IV), Chulalongkorn, Vajiravudh, Prajadhipok, Ananda and Bhumibol.

Getty Images

But despite these amazing successes, Thailand’s present frontiers were not yet fixed. In 1825, the British sent a mission to Bangkok. They had annexed southern Burma and were extending their control over Malaya. The king was reluctant to give in to British demands, but his advisers warned him that Siam would meet the same fate as Burma unless the British were accommodated. In 1826, therefore, Siam concluded its first commercial treaty with a Western power. Under the treaty, Siam agreed to establish a uniform taxation system, to reduce taxes on foreign trade and to abolish some of the royal monopolies. As a result, Siam’s trade increased rapidly, many more foreigners settled in Bangkok and Western cultural influences began to spread. The kingdom became wealthier and its army better armed, but it now faced new challenges from Europe, rather than the old rivals Burma and Vietnam.

Under the threat of military pressure from France, a colonial power in Indochina since 1883, King Chulalongkorn (Rama V) was obliged to yield territory in the east, including western Cambodia, to the French. The British interceded to prevent further French aggression, but their price, in 1909, was British sovereignty over Thai-controlled Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis and Terengganu (part of present-day Malaysia) under the Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. Only when this had been signed did Siam finally assume its present frontiers.

Reel life beach

Numerous scenes from the movie The Beach (2000), starring Hollywood heart-throb Leonardo DiCaprio and based on the critically acclaimed novel by Alex Garland, were filmed on Phuket (at Surin, Ko Kaew and Kata beaches, Laem Promthep and Thalang), while the major part of the movie was shot at Maya Bay, Ko Phi Phi Ley. The film put the spotlight on the country in a positive way – indirectly promoting the attractions of Phuket to a worldwide audience – although at the time the filmmakers provoked criticism for allegedly altering the landscape. The main criticism today, ironically, is that the film caused excessive tourism on the island.

Military rule and modern times

In 1932, the Thai military staged a coup and ended the absolute power of the Chakri dynasty. Three years later, in 1935, King Rama VII abdicated, and Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII, 1935–46), who was then at school in Switzerland, was chosen to be the next monarch. For the next 15 years, Siam was without a resident monarch for the first time in its history, and power lay with the military. In 1939, military strongman Luang Phibunsongkhram ordered that the name of the country be changed from Siam to Thailand and adopted the current national flag.

In 1940, moving to align Thailand with the Japanese, Phibun launched a small-scale war against the Vichy French in Indochina, retaking western Cambodia, including Angkor and much of the coast. Subsequently, on 8 December 1941, Japan invaded Thailand as a springboard for its attack on the British in Malaya and Singapore. The Thai armed forces resisted for a few hours, but Phibun, now confident of a Japanese victory over the Allies, decided to enter a formal alliance with the Japanese. As a reward, he was permitted to occupy certain territories lost to the British, including northern Malaya. But in 1945, following the defeat of Japan, the new Thai government of Khuang Aphaiwong withdrew unilaterally from Malaya. Two years later, Thailand withdrew from western Cambodia as well.

In June 1946, King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) ascended the throne, and remained king until his death in October 2016. He was the longest reigning head of state in the world at the time of his death (for more information, click here).

Thai leader Phibunsongkhram (bottom right) with US President Eisenhower in the 1950s.

US National Archives

The Post-war era

Since 1932, Thailand has endured 19 coups and had nearly 60 prime ministers, although some have served several terms. All governments were led by the military between 1946 and 1973, when a clique of generals dubbed ‘the Three Tyrants’ employed martial law. Clashes on 14 October 1973 between troops and protesting students at Democracy Monument left many students dead, and the Three Tyrants fled to the US.

After a brief civilian government, in 1976 one of the generals, Thanom, returned, sparking protests. On 6 October, police, troops and paramilitary organisations stormed Thammasat University. Within hours, the army regained power.

For the next decade, relatively moderate military rule laid the foundations for new elections, which ushered in a civilian government, until another coup, this one bloodless, in 1991. The following year, more than 100 pro-democracy demonstrators were wounded or killed.

King Bhumibol brokered reconciliation, and a series of elected governments followed. In 1997, Thailand’s economic crash triggered the Asian financial crisis.

Pattaya and sex tourism

Tourism really began to develop along Thailand’s southeast coast in the 1970s, gradually transforming and enriching a region that had traditionally been dependent on farming and fishing. Perhaps the most infamous and uncontrolled transformation occurred in Pattaya, where prostitution is rife.

Prostitution was made illegal in 1960, although the law is rarely enforced, and sex is openly for sale in go-go bars, brothels and massage parlours. In part this is because it is an accepted and common practice for Thai men to patronise prostitutes or have a mia noi (‘little wife’).

Sex tourism escalated with American troops taking R&R during the Vietnam War, and, by the 1980s, planeloads of men were flying in for the purpose. Many sex-workers, both male and female, come from northeast Thailand, where incomes are the lowest in the country. Many cross-cultural marriages have started in a brothel, and government figures often cite foreign husbands in northeastern villages as being significant contributors to GDP.

NGOs estimate between 200,000 and 300,000 sex workers in Thailand. Having found that few are motivated to leave the business, extricating workers is no longer their primary focus. Organisations such as Empower instead educate workers about the dangers of HIV, and teach them English so they are less likely to be exploited by clients.

Thaksin Shinawatra

Following the 2001 elections, the new prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra proved immediately controversial. He faced corruption charges and was condemned for suppressing the media and for his ‘War on Drugs’, in which hundreds were killed. But he also introduced loans and cheap health care for the poor. As he became wildly popular in poorer rural areas, he was irritating traditional powers in Bangkok.

In 2005, anti-Thaksin demonstrators adopted the colour yellow to show allegiance to the monarchy, becoming known as the Yellow Shirts. In September 2006, Thaksin was ousted in a military coup.

As Thaksin lived in exile, his followers, calling themselves the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD), and wearing red shirts, also protested. A Thaksin proxy, the People Power Party (PPP) won the next general election in December 2007, and Thaksin returned the following year, only to later skip bail on corruption charges and flee once again to London.

Thaksin spearheaded a goodwill gesture in 2004 to airdrop paper cranes over the troubled south.

Getty Images

Red Shirt, Yellow Shirt

Yellow Shirt demonstrations resumed and, during late 2008, they seized the airport, bringing the country to a standstill. In December 2008, the courts disbanded the ruling party and, in a deal widely seen as brokered by the army, the Democrat Party took office, with Abhisit Vejjajiva as prime minister, bringing the Red Shirts back to the streets.

In April 2009, the Red Shirts disrupted the ASEAN summit in Pattaya, and heads of state were airlifted to safety; Songkran riots erupted in Bangkok; and PAD (Yellow Shirts) leader Sondhi Limthongkul was shot, but survived.

In February 2010, Thaksin was found guilty of abuse of power and had assets of B46 billion confiscated. In April and May, thousands of Red Shirts occupied parts of Bangkok, closing Pathumwan shopping malls for several weeks. Eighty-five people were killed and nearly 1,500 injured in clashes with the army.

In 2011, the Thaksin proxy Pheu Thai Party, led by his sister Yingluck, won a landslide election victory and Yingluck became Thailand’s first female prime minister. Her early months, already difficult, were severely tested by the worst floods in decades, which saw large parts of the north, northeast and central regions inundated. The government endured heavy criticism for diverting flood waters towards poorer communities to save central Bangkok.

During 2012 the government pushed for a change to the Constitution and a general amnesty for post-coup events. This was seen as an attempt to return Thaksin’s confiscated assets and allow him a comeback to the country. It led to 100,000 people taking to the streets in protest in 2013.

The amendments to the amnesty bill were not passed, but the protests did not stop. A new movement called the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) emerged. As the movement gained popularity, it made increasing demands. As a result, parliament was dissolved and an election scheduled for February 2014. Voting was disrupted by the PDRC and the election annulled. Yingluck was removed from her office on 7 May 2014.

On 22 May, two days after the Royal Thai Army introduced martial law, General Prayuth Chan-ocha took power in a military coup. The junta dissolved the government and senate and repealed the constitution. On 26 May, the King formally acknowledged the coup and appointed General Prayuth Chan-ocha to run the country.

Death of the king

On 13 October 2016, King Bhumibol Adulyadej passed away after a long illness. The country was wrapped in mourning for a year, until the late king’s cremation ceremony on 26 October 2017.

The king was succeeded by his second child and only son, Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn. He is not as popular or respected by the Thai people, being criticised for living a ‘playboy’ life; he has been married three times, each ending with a divorce.

King Vajiralongkorn’s reign started at a difficult time; the country fractured by a decade of political clashes and two coups which led to military rule. The country is also preparing for a general election which is scheduled for 2018.

Phuket’s Vegetarian Festival

Devotees striking their heads with axe blades, cutting their tongues with knives and rolling in broken glass are common sights at the Vegetarian Festival.

According to legend, early Chinese settlers who arrived in Phuket 200 years ago witnessed the origins of the island’s most unusual event, the Phuket Vegetarian Festival. The festival is celebrated in the first nine days of the ninth month of the Chinese lunar calendar, usually in late September or early October.

During the event devout Taoist Chinese and many other Thais abstain from eating meat. In Phuket Town, the festival’s activities centre on six Chinese temples, with Jui Tui Temple (for more information, click here), on Thanon Ranong, the most important, followed by Bang Niew Temple and Sui Boon Tong Temple. The festival is also observed around the country, including Kathu Town in Phuket (where the Vegetarian Festival is believed to have originated), Bangkok and also at Trang Town in Trang Province.

Bizarre and extraordinary

Devotees at the Vegetarian Festival organise processions, make temple offerings, stage cultural shows and consult with mediums. They also perform a series of bizarre and extraordinary acts of self-mortification that, to the uninitiated, seem scarcely credible. Devotees enter into a trance designed to bring the gods to earth to participate in the festival, then walk with bare soles on red-hot coals, climb ladders made of razor-sharp sword blades, stab themselves with all manner of sharp objects, and pierce their cheeks with sharpened stakes, swords, daggers and even screwdrivers. It can be a bloody and disconcerting sight. Miraculously, little permanent damage seems to be done.

The opening event is the raising of the 10-metre (30ft) -tall lantern pole to notify the gods that the festival is about to begin. Meanwhile, altars are set up along major roads bearing offerings of fruit and flowers, incense, candles and nine tiny cups of tea. These are for the Nine Emperor Gods of the Taoist pantheon invited to participate in the festival and in whose honour the celebrations are held. Thousands of locals and visitors line the streets to observe the events, which are accompanied by loud music and frenzied dancing.

Phuket’s Chinese community claims that a visiting theatrical troupe from Fujian almost two centuries ago first began the festival. The story goes that the troupe was stricken with a strange illness because its members had failed to propitiate the Nine Emperor Gods. In order to recover, they had to perform a nine-day penance, after which they became well.

Everyone can enjoy specially prepared vegetarian food at street stalls and markets all over the island. Strangely, these vegetarian dishes, in Thai or Chinese style, are made to resemble meat. Though made from soy or other vegetable substitutes, the food looks and often tastes very much like chicken, pork or duck.

Ritual self-mortification at the festival.

Getty Images