Thailand is an overwhelmingly Buddhist nation. Around 95 percent of the population follow Buddhism, and its influence is apparent almost everywhere. Only in the very far south of the country, on the border with Malaysia, does Islam predominate.

Khao Luang cave temple, Petchaburi.

Alamy

The Way of the Elders

The main form of Buddhism practised is Theravada, or the ‘Way of the Elders’, though in Chinese temples, the Mahayana, or ‘Greater Vehicle’ tradition, may be found alongside Taoist and Confucian images. Both traditions teach that desire for worldly things leads to suffering, and that the only way to alleviate this suffering is to cast off desire. Theravada Buddhism emphasises personal salvation rather than the Mahayana way of the bodhisattva, which is the temporary renunciation of personal salvation in order to help humanity achieve enlightenment. The goal of the Theravadin is to become an arhat, or ‘worthy one’.

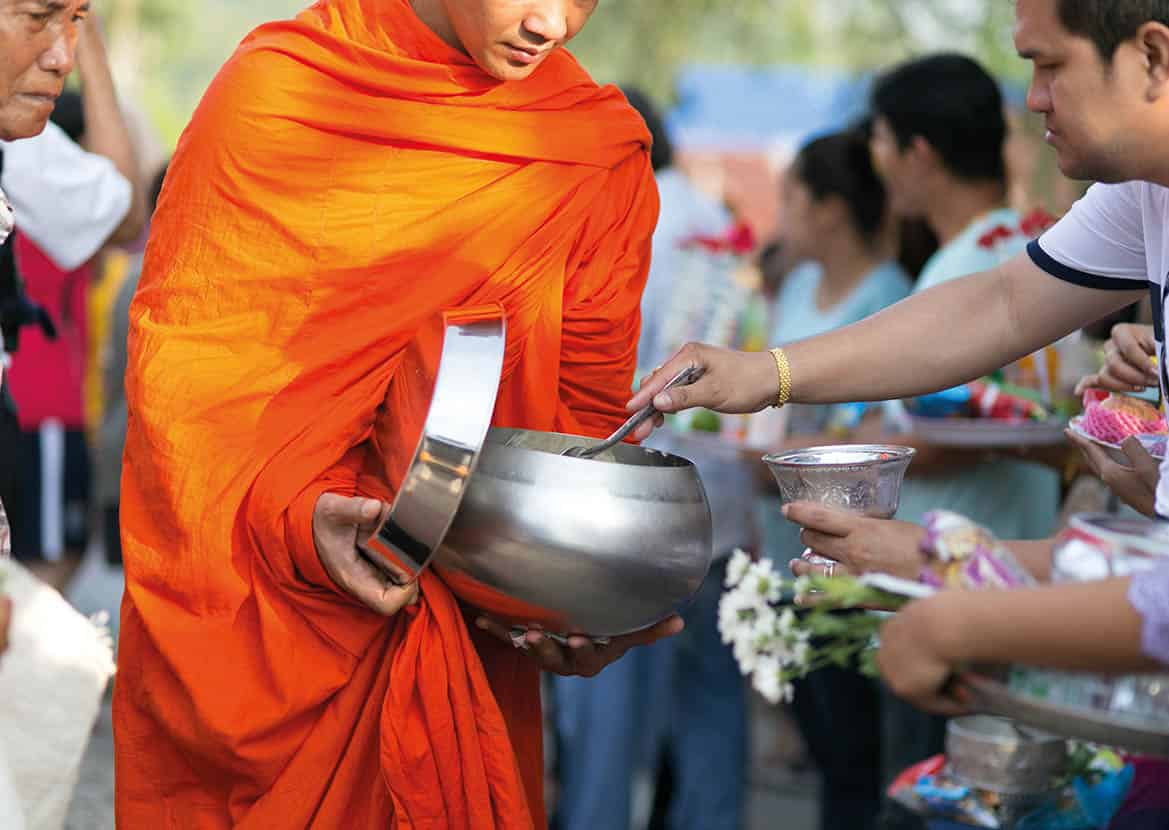

A monk collecting alms food.

Shutterstock

In practice, most Thais hope that by ‘making merit’ and honouring the triratna, or ‘Three Jewels’ – the Buddha, the sangha (order of monks) and the dharma (sacred teachings) – they will attain a better rebirth and ultimately attain nirvana, or enlightenment. To do this, one should strive to build up positive karma. This may best be achieved by not taking life, abstaining from drinking alcohol and other intoxicants, avoiding gambling and sexual promiscuity, keeping calm and not becoming angry, as well as honouring the elderly, monks and the Thai monarchy. Most Thai Buddhist men will join the sangha and become monks at least once in their lives. Women, too, may be ordained as nuns, though fewer are, and the act is usually delayed until old age, when the task of raising children has been completed.

Appeasing the spirits

Spirit worship plays a major, if informal, role in Thai religious life, alongside the practice of Buddhism. It is widely accepted that there are spirits everywhere – spirits of the water, wind and woods, and both locality spirits and tutelary spirits. These spirits are not so much good or bad, but are powerful and unpredictable. Moreover, they have many of the foibles of humans, being capable of vindictiveness, lust, jealousy, greed and malice. To appease them, offerings must be made, and since they display many aspects of human nature, these offerings are often what people would value themselves.

The city foundation pillar of Bangkok.

Alamy

To counteract the spirits and potential dangers in life, protective spells are cast and kept in small amulets mostly worn around the neck. Curiously, the amulets are not bought, but rather rented on an indefinite lease from ‘landlords’, often monks considered to possess magical powers. Some monasteries have been turned into highly profitable factories for the production of amulets. There are amulets that offer protection against accidents while travelling or against bullet and knife wounds; some even boost sexual attraction. All this has no more to do with Buddhism than the protective blue-patterned tattoos sported by some rural Thais to ward off evil.

Consecrating a spirit house

Setting up a spirit house, or san phra phum, is not a casual undertaking, but one that requires the services of an experienced professional. Usually, this is a Brahmin priest called a phram (dressed in white, in contrast to the Buddhist saffron robes), or at least someone schooled in Brahmin ritual.

The consecration ritual is commenced by scattering small coins around the site chosen for the new spirit house, and in the soil beneath the foundations. Then the spirit house is raised and offerings are made. These include flowers (usually elegant garlands of jasmine), money, candles and incense – the last often stuck into the crown of a pig’s head.

The phram, together with the householder and his various relatives and friends, then prays to the spirits, beseeching the local chao thii, or Lord of the Locality, to take up residence in the new spirit house.

Spirit houses are often beautifully decorated, and to entice the chao thii into its new home, various inducements are generally added. These may include traditional offerings such as statues of dancers, ponies, servants and other necessities made of plaster or wood. In more recent times, items such as cars and other modern consumer desirables have been offered as well, each carefully chosen to catch the spirit’s fancy.

The city pillar

It is not known exactly when the Thai people first embraced a belief in spirits, but it was most probably long before their migration south into present-day Thailand, and certainly before their gradual conversion to Buddhism around 700–1200 AD. When the first Thai migrants established themselves in the plains around Sukhothai, their basic unit of organisation was the muang, a group of villages under the control and protection of a wiang, or fortified town. Of crucial importance to each muang, and located at the centre of each wiang, was the city pillar, or lak muang. To this day, it is a feature of towns in Thailand.

The lak muang – generally a rounded pole thought to represent a rice shoot – is the home of the guardian spirits of the city and surrounding district. It should be venerated on a regular basis, and an annual ceremony, with offerings of incense, flowers and candles, must also be held to ensure the continuing prosperity and safety of the muang. Long ago, during the region’s animist past, the raising of city pillars was often associated with brutal rituals involving human sacrifice.

Fortunately, such rituals have long since disappeared from the scene, as gentler traditions associated with Theravada Buddhism have modified spirit beliefs. Today, some lak muang are topped by a gilded image of the Buddha.

A typical spirit shrine in Thailand.

Marcus Wilson Smith/Apa Publications

Spirit houses

For many centuries, offerings have been made when land had to be cleared for agriculture or building. After all, the spirits of a place are its original owners, and their feelings have to be taken into consideration. At some point, it was decided that an effective way of placating a locality spirit was to build it a small house, or san phra phum, of its own. That way, it would be comfortable, content and, above all, would not want to move in with its human neighbours!

Thai Buddhists believe that every human house should have its own spirit house for the wellbeing of the locality spirit. These may be anywhere in the garden (even, in big cities, on the roof), with the important proviso that the shadow of human habitation should never fall on the spirit house. Shops and commercial establishments have their own spirit houses as well, often positioned to counteract the power of rival establishments’ spirits.

Phallus shrine

Certain spirit shrines, or their residents, are thought to have powers to redress specific problems. An example is the shrine of Chao Mae Thapthim, a female deity considered to reside in a venerable banyan tree, just behind Bangkok’s Swissôtel Nai Lert Park. Mae Thapthim has the power to induce fertility, and many young women seeking to become pregnant visit the shrine. They leave the usual presents of flowers and incense, as well as a less common type of offering – wooden phalluses that come in all sizes, from a few centimetres long to giant representations extending over a metre and a half, standing on legs or even wheels.

The association of Buddhism with spirit worship has been a two-way process. There is hardly a Buddhist temple in the country that does not incorporate an elaborate spirit house in its grounds – built at the same time as the consecration of the temple in order to accommodate the displaced locality spirits.

Bangkok’s Chao Mae Thapthim shrine.

Jason Lang/Apa Publications

As if this weren’t enough, the Thais also feel obliged to consider the world outside the muang. If the lak muang is the centre of civilisation and safety, the jungled hills and inaccessible mountains are the opposite. It is no surprise that the Thais erect spirit houses along the roads linking their settlements, paying particular attention to threatening or ominous landscapes. Even today, every pass or steep section of road is topped by a spirit house to accommodate the inconvenienced locality spirit. Passing drivers beep their horns in salutation, and many stop to make offerings. Spirit houses are also raised in fields to ensure the safety of the crop.

Boys at a Muslim school in Kamala, Phuket.

John W. Ishii/Apa Publications

Islam in the south

It is only in the furthest south of peninsular Thailand, in Malay-speaking territory, that temples and spirit houses disappear, replaced by minarets and mosques. Islam first came to this region in the 8th century. Carried across the Indian Ocean by Arab and South Indian traders, it found fertile ground among the region’s Malay-speaking people. The Muslim tradition of Thailand’s deep south is Sunni Islam of the Shafi’i school, as in neighbouring Malaysia.

When the first Muslims arrived, they settled and intermarried with the local Malay population, most of whom at the time practised a syncretic Hindu-Buddhist belief. By Islamic law, the children of such unions were raised as Muslims, and, over the centuries, a combination of intermarriage and proselytising led to the conversion of almost all the indigenous Malay peoples.

Witch doctors

There is an older spirit tradition practised by many Thai Muslims in the Malay-speaking south. Though widely believed in by most ordinary folk, it is officially condemned by orthodox Muslim teachers. This tradition is represented by the bomoh, or Malay ‘witch doctor’, who can foretell future events, cure physical, mental and spiritual diseases, curse individuals or lift such curses. The witch doctors rely on a fascinating mix of folk Islam overlaying a deep vein of other traditions that predate Islam in the region. Because of this syncretism, which is completely forbidden in orthodox Islam, much of bomoh practice is concealed from outsiders.

Comprising less than 5 percent of the population, Thai Muslims are a tiny minority, only dominant in the four southern provinces of Satun, Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat. In this region, the people are conservative, generally working as farmers or fisherfolk, studying the faith in religious schools, and saving to go on the haj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca. The Shafi’i school is traditional and not overly rigorous. However, home-grown radicalism and fundamentalist influences from abroad have injected new fervour into the small insurgent groups behind the increasingly violent separatist movement in Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat provinces. Satun Province, although largely Muslim, has steered clear of such strife and unrest, and is safe to visit.

From Buddhism to modern spa

Massage, with its Buddhist origins, is an inherent part of normal life in Thailand and this makes spa treatments a natural Thai experience.

Travelling monks arrived in Thailand in the 2nd or 3rd century AD, bearing not only Buddhism, but also nuad paen boran (ancient massage), which legend says was developed from Indian Vedic treatments by Shivakar Kumar Baccha, the Buddha’s own medical adviser. Nearly 2,000 years after it entered the country, the world now calls it simply Thai massage. It is one of many treatments that are now available in the modern spas that are an enticing feature of the Thailand beach holiday.

The association with the country’s religious philosophy means that the most dedicated masseurs still perform the service within the Buddhist concept of mindfulness. Before they start, true adherents will make a wai (a slight bow with hands clasped together) to pay respects to their teacher and focus on metta (loving kindness), thought to be the ideal state of mind in which to give massage.

Places of healing

For centuries, throughout Thailand, temples were places of healing, and they administered many of the treatments we now associate with modern spas, such as herbal compresses and herbal medicines.

As it is based on ancient Indian teachings, Thai massage includes the stretching elements of yoga alongside acupressure and reflexology. There should also be a meditative quality, although low-budget shops may have music or TV playing that scupper this. The massage principle revolves around 10 energy lines, called sip sen, believed to carry physical, emotional, and spiritual energy between meridian points around the body. When the lines become blocked, illness or emotional stress occurs, so they must be reopened.

The experience is usually vigorous, employing push-and-pull stretching of tendons and joints and deep-tissue kneading with elbows, knees and feet and fingers, so it is not a suitable treatment for people with back, neck or joint problems. Bow bow, kap/ka is a useful phrase, meaning ‘softer, please’. Sometimes an ointment is used on painful muscles – Tiger balm is the most famous brand – but generally there are no oils involved.

The most common operations are in small houses consisting of little more than several mattresses on the floor, curtained off from each other. These places can be found on many streets, particularly in tourist areas, and provide exquisite relaxation for as little as B250 an hour.

Urban spas, often in traditional teak houses, may include beauty elements such as body scrubs and facial treatments, while luxurious resort spas offer the gamut of ‘wellness’ options, from massage to Traditional Chinese medicine, reiki, meditation, hypnotherapy and New Age treatments such as crystals and floral essences.

Massages in Thailand aim to reopen blocked lines of energy around the body.

iStock