4

Showstopper

Courtesy of the author

My biggest problem growing up . . . was that I wasn’t growing up. I was a titch. A short-arse. Vertically challenged, as the condition is probably known today. I’d always been one of the smallest in my class, of course – and my ‘little’ brother Maurice had always been a few inches taller than me. But by the time I started at Dunston Hill Secondary Modern, most of my friends were five-foot-something and counting . . . while I was stuck in the mid-fours. Even Victor had shot up past me, and the way things were going, I was worried that my little sister Julie would be catching up soon.

With every week and month that passed – without so much as a fraction of an inch in growth to show for it – my situation became more desperate.

Then one day I was skimming through the back pages of a boys’ magazine when I came across an advertisement for a ‘practical book’ that seemed like the answer to all my prayers. The Morley Method of Scientific Height Development was the title – written by a world-famous authority on childhood growth named John Morley. So, of course, I rushed down the Post Office, bought myself a postal order for the price of the book, and sent it off to the address in the advertisement.

A week later, the book was waiting for me on the front mat when I got home from school. ‘Congratulations!’ read the inside cover. ‘You are holding in your hands The Famous Morley Method, with which you can increase your height in just twelve days!’

I almost cried, I was so relieved.

The book turned out to be even more helpful than I’d expected. Within just a few chapters, I’d learned that the best way to grow taller was to harness ‘nature’s magnetic forces’ and sleep with my head pointing north and my feet pointing south. Why hadn’t anyone told me this before? So off I went to find my dad’s compass, and when it was time for bed, I arranged myself on the mattress accordingly. I couldn’t get the angle exactly right, mind you, because there were two other Johnsons in the same bed – both of whom seemed to be getting bigger by the day. Maybe that’s why it wasn’t working, I thought, as Day Twelve came and went.

Then another twelve days passed.

Then another.

And guess what?

I was still four-foot-six.

Now, at this point, as you might expect, I was starting to wonder if John Morley really was a world-famous authority on childhood growth. I mean, when I looked in the back of the book at the other titles he’d written, I discovered that he was also a world-famous authority on balding, healthy feet, magnetic super-strength, profitable stamp-dealing, weight-gain, jiu-jitsu, building a powerful chest, strong sight (without glasses), ‘scientific boxing’ and bashfulness. Meanwhile, he claimed that the most common cause of shortness was ‘slouching’, which was enough of a leap to make even my gullible pre-pubescent mind go . . . what? Surely, whether you were slouching or not, you were still the same height. Then I noticed that all of the endorsements on the back were from kids who said they’d risen by several inches after reading the book, which, when I thought about it for a second, was exactly what would have happened anyway through natural growth.

But I refused to believe that I’d been conned. So, I kept reading and re-reading each chapter, staying up later and later every night, searching for missed advice, a hidden clue, anything . . . until my dad realized what was going on and sat me down for a talk.

‘Son,’ he growled, ‘you’ve always been a t’arse, and you always will be a t’arse.’ (My dad never swore, so ‘t’arse’ was his version of ‘short arse’.) ‘Now, for God’s sake get your nose out of that stupid book and start making the best of what you’ve got.’

To be fair to my old man, he did give me some helpful advice about my height – mainly because he was worried that in a town full of hard men who liked to pick fights, a kid of my size was a walking liability. I mean, my dad was short too, but he was an absolute pit bull of a guy, which was how he’d managed to survive five years of death and destruction during World War II.

But he was under no illusions about my fighting skills. ‘You’re just not big enough, son,’ he told me, ‘so, if you find yourself in any trouble, turn around and walk the other way. And if you can’t do that, nut them as hard as you can on the nose . . . then run.’ This tried-and-tested manoeuvre, my dad added, was called ‘a Newcastle kiss’.

He’d been right to worry, it turned out, because I soon found myself having to fend off an attacker.

I had a part-time job as a milk delivery boy at the time, which meant getting up at 5 a.m., running up the hill to Youens’ Dairy, loading up a little Austin A50 van – they also had a horse and cart – and hanging onto the back of it, delivering bottles to the houses as we passed them. It was a tricky job because there were all kinds of milk – silver top, red top, green top, gold top and, most expensive of all, brown top from Jersey cows, which only went to doctors and headmasters. So, you had to pay attention, and you also had to make sure you didn’t fall off the back of the van – and usually you had to do both of those things even when it was raining, sleeting or snowing, and while a North Sea wind was trying to take off your face.

The second my milk round finished, I should add, I had to dash over to the newsagent’s and start my paper round. By the time I got to school, I’d already been at work for more than two hours. But I loved my jobs. Especially on Saturdays, when the milk van driver, Lettie, would take me to the baker’s after our round, and I’d get a meat square straight out of the oven, which would burn my mouth and tongue, but it didn’t matter because I’d wash it down straight after with a half-pint of full-cream milk. Then I’d get paid and I’d go and buy myself a model aeroplane.

Ah, just fantastic stuff.

Anyway, the trouble started with the last milk round before Christmas, when people would come out of their houses and give me tips. I collected £2 in total that morning – which I’d decided to spend on Christmas presents for my ma and dad.

But there was a big, nasty bully of a kid who also worked at the dairy – I won’t mention his name – and he must have heard about my tips because he followed me out of the building after my shift, cornered me in a shop doorway, and demanded that I hand over the money. No reason. He just thought he could get away with it.

No.

So, he drew himself up to his full height, pulled me up by the collar so my face met his, and went, ‘I’ll ask you one more time, you little shit . . . give me your money.’

All I could think of were my dad’s words about turning around and walking away. But I was up against a door, so there was no escape. And as a matter of principle, I wasn’t going to give this guy a single penny. So, without even thinking – as a surge of pure animal rage took over me – I nutted him so hard, right between the eyes, it broke his nose and his cheekbone. The scream he let out was awful. Even I was shocked. Then he started to cry, and of course there was blood dripping everywhere. But I didn’t feel sorry for him. He’d tried to rob me because I was small, and as my dad would say, he had it coming. So, I left him there and legged it home, looking over my shoulder all the way, just in case he’d followed me.

The police were never called. But when I went back to work after Christmas, Lettie’s sister tore into me, calling me every name that she could think of. ‘You little Italian pig,’ she spat. ‘you should be ashamed of yourself, fighting like a dirty foreigner.’

Lettie pointed out that it was the older boy who’d started it by trying to steal my tips – and that he had a long history of being lazy and rude and nicking milk from the van.

‘Aye, but we cannit sack him,’ came the reply. ‘He’s English.’

I kept my job, and he didn’t. Lettie was a hero to me. She stuck up for me, and that meant everything, at a tough time.

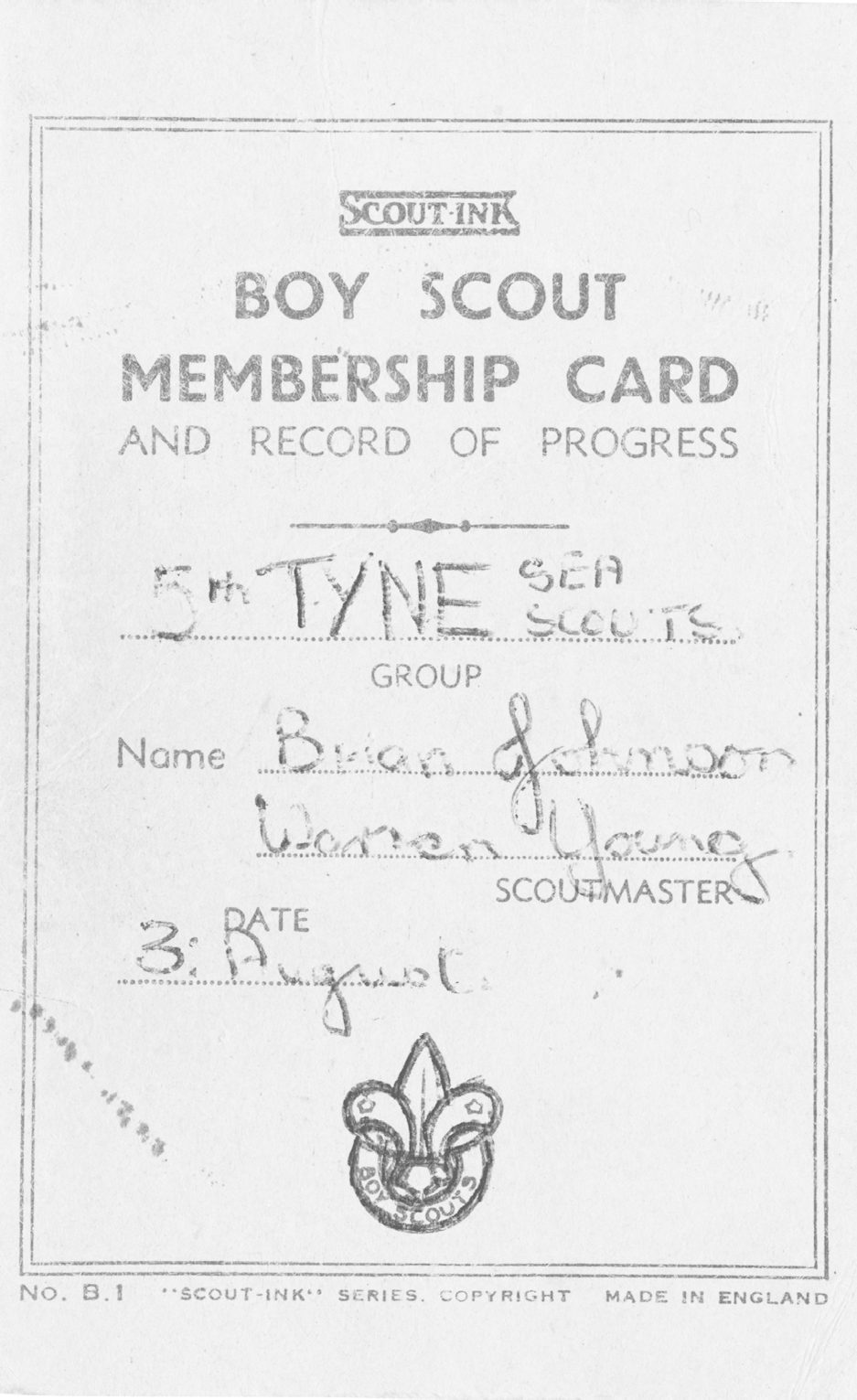

The one shining beacon of light for me during my late childhood and early teenage years was the Fifth Tyne Sea Scouts. If you’re not familiar with the various branches of the Scouts, the Sea Scouts are just like the ordinary Scouts, but with a focus on boats and water – and, of course, there are plenty of both in Tyneside, which once stood alongside Glasgow and Belfast as one of the shipbuilding capitals of the world. But the purpose of the little troop I joined was really more to introduce working-class kids like me to the world beyond our grey, polluted and increasingly rundown industrial surroundings. Which is exactly what it did.

Without the Sea Scouts, I’m pretty sure that my life wouldn’t have turned out the way it did.

A lot of this was down to our Scoutmaster and my first mentor, a young guy who went by the name of Warren Young . . . because apparently when I was born, the clouds parted, a shaft of light shone down, and God boomed, ‘AND LO, EVERY IMPORTANT FIGURE IN THE LIFE OF THIS CHILD BRIAN SHALL BE CALLED “YOUNG”.’

I mean, granted, Warren Young was a bit of an oddball – a bachelor who still lived with his mother in a big old house in Gateshead – but he was the loveliest, kindest, most thoughtful man that I’d ever met. He didn’t shout at you if you made a mistake. He’d always listen to what you had to say. And he’d always help you if he could.

To understand just how rare that was back then, bear in mind that it was entirely normal in those days – expected, even – for figures of authority to treat kids in ways that would get them locked up today. Back at Dunston Hill juniors, for example, I was once reading out loud in front of the class and got it a little wrong, and the teacher came up behind me and smacked me on the side of the head so hard I fell down and couldn’t get back up.

It was criminal, the force he used. And he kept screaming at me to get up, but I couldn’t, so he had to ask one of my classmates to get the school nurse. I thought he’d get into trouble for it, but not at all – he was back to knocking kids around the next day.

The point being that Warren Young was halfway to a saint because he was so patient and kind – and we respected him all the more for it. We also loved him because he was always coming up with new games and activities for us, including endless rounds of ‘British Bulldog’, during which we got to knock the living shit out of each other in the Scout hut for half an hour at a time, even though one of the Little ones would nearly always end up going home with half of his teeth in a paper bag.

But the games weren’t my favourite part of the Sea Scouts. Not by a long shot. What I loved the most . . . was the singing. Because it wasn’t the boring, stodgy singing that we did at school or in church. It was boisterous, sitting-around-a-campfire, bellowing-it-out-at-the-top-of-your-lungs singing – the kind that makes your spine tingle and puts a huge grin on your face, no matter what kind of mood you’re in.

Another reason I liked the singing so much was because I was starting to realize that I was good at it.

It’s funny, looking back, that I could belt out a tune even though my voice hadn’t broken yet and I was still so underdeveloped. I suppose I just got the ‘huge pair of lungs’ gene from my dad. Where my pitch came from, though, I’ve no idea. My dad couldn’t hold a tune to save his life. My mother, God bless her, was even worse.

So, there I’d be in the Scout hut every week, and sometimes even at the weekends, dressed up in my little neckerchief and woggle, my knees and arms all bruised and grazed from British Bulldog, singing my heart out, imagining myself somewhere on the plains of Africa . . . just loving every second of it. And then one day, Warren Young took me aside and told me something that would change my life forever.

‘Brian, son,’ he said, ‘I want you to come back here on Tuesday afternoon – for an audition.’

‘An audition?’ I said, my face dropping – I wasn’t quite sure if this was a good thing or a punishment for something that I’d done wrong. ‘What d’you mean . . . audition . . . ?’

‘Well, the Scout leaders have had a meeting and we’ve decided it’s high time we put on a Gang Show,’ he said. ‘And with that voice of yours . . . I think you should be in it.’

Of course, the whole Scout troop would be in it, but he said he wanted me to sing a song solo.

That stopped me in my tracks a tadge.

Now, Gang Shows in those days were pretty awful events – like school pantomimes, only worse. But entertainment was hard to come by in the early 1960s, so everyone wanted to pile into the Scout hut to watch two hours of lads cracking jokes, dancing and singing songs that everyone knew by heart.

Gang Shows had started thirty years earlier with the songwriter and producer Ralph Reader, the guy who wrote ‘We’re Riding Along on the Crest of a Wave’.

So, getting the chance to be a part of this great British institution was a massive honour – and an opportunity that could very well change my life. But first I had to get through my audition with the show’s ‘musical director’, a much older guy named Mr. Tedd Potts, who had greased back hair and a very affected, theatrical manner.

I was so nervous, I barely ate or slept for days.

I shouldn’t have worried, though, because it turned out to be a mass-audition of Scouts from all kinds of different troops, from all around the area – and all we had to do was skip around in a circle while a guy played the piano and Mr. Tedd Potts watched our every move in a slightly unsettling way. Later on, I was told that I’d passed with flying colours and would be getting four songs to sing. A chance to sing in front of a live audience for the first time.

And then we were taught very roughly how to dance. It wasn’t dancing, it was more marching and waving hands. It was George, Raymond, Carl – all friends of mine from the Scout troop and Beech Drive. My voice wasn’t broken, it wasn’t anything to shake the world, but I held a note true. There were a lot of warblers, but I seemed to be able to hold onto a note without thinking about it. The songs were ‘Stay after School’, ‘The Morning of My Life’, ‘Sisters’ and one other.

The first dress rehearsal was in the church hall and we were all dressed up, with the piano and lights. Even though there wasn’t anybody there, it was quite nerve-wracking. We had to make costume changes, running downstairs to a room buzzing with activity. All the mothers were helping with makeup, and the makeup was bad because of how bad the lights were. We had to have red cheeks and we looked like mannequins. The wonderful thing was the excitement, which I’d never felt before, like I was part of something. People were tripping up, walking off stage and walking into things, and boys were getting a bollocking. It was just a fantastic feeling; I knew this was the life for me.

I was nervous because there was this one song, ‘Stay after School’, that was quite rocky. I had to wear jeans, but I didn’t have any at the time so I was given a pair with a T-shirt. When we went out to do it on the live show, the girls were screaming, which we loved. Our hair was slicked back, and we wore sneakers. I was so wrapped up in our performance that I didn’t think about the parents, but my mother thought we were lovely. To me, it was like there were thousands there in that church hall.

The awful thing was that we only had two performances, a Friday night one and a Saturday night one, and then it was over. I felt like I had nothing to do because before the show we would rehearse twice a week and now, nothing.