CHAPTER 2 The Sash My Father Wore

Cursèd be he that curses his mother. I cannot be

Anyone else than what this land engendered me:

… I can say Ireland is hooey, Ireland is

A gallery of fake tapestries,

But I cannot deny my past to which my self is wed,

The woven figure cannot undo its thread.

Louis MacNeice, “Valediction” (1934)

IN THE SMALL HOURS OF the morning of Tuesday, April 2, 1912, before the electric trams with their recently added roofs commenced their shuttle into the city center, a Renault motor-car waited on tree-lined Windsor Avenue in south Belfast.1 The residential street, full of alternating white and redbrick mansions, ran between the Lisburn and Malone roads, the axis of upwardly mobile prosperity that was both child and parent of the city’s most affluent suburb. Like Windsor Avenue’s homage to Britain’s most famous castle, many of Malone’s public spaces had adopted royally inspired names which proclaimed the area’s loyalty to the throne along with, perhaps, a faint sense of self-identified social kinship with its incumbent. Twenty years earlier, the residents had ditched the workaday address of Stockman’s Lane, at the bottom of the Malone Road, to rechristen it Balmoral Avenue, in a nod to Queen Victoria’s favorite home.2 Nearby, various streets and stations were named in honor of Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, William IV’s queen; Belvoir and Deramore honored a late Tory baron; the Annadale embankment, which lines the slow-flowing waters of the Lagan River where young medical students practiced their rowing on weekend mornings, was named for another deceased local aristocrat, Anne Wellesley, Countess of Mornington.3 Later, when a school was founded near the Annadale embankment, it was called Wellington after Anne Wellesley’s son, the 1st Duke of Wellington.4 Shaftesbury Square, the urban gateway to south Belfast, bore the name of an earldom with historic influence in the north of Ireland, while multiple streets and buildings paid tribute to the Chichester family and their marquessate of Donegall.I There were various parks, roads, and avenues with the prefix of Osborne in honor of Queen Victoria’s former summer house on the Isle of Wight, while Sans Souci Park, near the top of the Malone Road, widened the geography of homage, if not the class, by choosing as its inspiration the baroque palace built for King Friedrich the Great of Prussia.

In neighboring Stranmillis, the suburb that intersects Malone, a new street was given the name Pretoria to commemorate imperial victories in southern Africa. On the other side of the river, the Ormeau neighborhood created roads called Agra, Baroda, and Delhi, after areas of the British Empire in India. Botanic, the final stretch of land before south Belfast gave way to the city center, contained new avenues named after seventeenth-century British generals or, like Candahar Street, to celebrate successful colonial expeditions into Afghanistan.5

From his home on Windsor Avenue, Thomas Andrews, the thirty-nine-year-old managing director of the Harland and Wolff shipyards, stepped into his waiting car before it turned towards the Malone Road.6 He left behind his wife of four years, Helen, and their two-year-old daughter, Elizabeth. Andrews, who would be gone for several weeks supervising the maiden voyage of the Titanic, was ambitious and almost fanatically dedicated to his career, but when he traveled he suffered dreadfully from homesickness, particularly after the arrival of little Elizabeth.7 One of the five servants they employed was a nurse for the toddler.8 His car turned left onto Malone to continue its journey towards east Belfast, where the Titanic was docked in preparation for her sea trials.

Thomas Andrews, c. 1912.

Tall and softly handsome, with a trim build, dark hair, and brown eyes, Andrews—known as Tommy to his family and closest friends—had the elegant manners and unfailing kindness with which even the most exacting of aristocratic etiquette experts would have struggled to find fault. His work in the shipyards brought him into regular contact with men from all walks of life—be they industrialists, like his uncle Lord Pirrie, or semiliterate laborers from east Belfast, some of whom brought their seven- or eight-year-old sons to work in the shipyard because they could not afford to send them to school. Andrews’s total lack of snobbery, his sense of fairness, and his gentle tone in conversation endeared him to most of his colleagues and helped spare him from accusations of nepotism.9

As Andrews’s automobile moved down the gentle slope that marked the end of the Malone Road, he passed the still-slumbering accommodation of the four hundred or so students of Methodist College.10 A boarding school with a white Maltese cross for its crest, “Methody,” as it was known by locals and alumni, had a stellar reputation for academics and sports. Two weeks earlier, its rugby team had competed in the Ulster Schools’ Cup Final, a match held annually in Belfast on St. Patrick’s Day, in which the two best squads in the north of Ireland play against one another. That March, rather gratifyingly for Tommy Andrews, Methody had played and lost 11–3 against his own alma mater, the Royal Belfast Academical Institute.11

“Inst,” as it was and is referred to for reasons of ease, laziness, and affection, lay less than a mile from Methody. Tommy Andrews, like his brothers John, James, and William, was proud of their status as “Old Instonians,” regularly contributing to fund-raising for the school sports and prizes. Cricket had been one of Andrews’s favorite clubs as a pupil and he retained a keen interest in the sport.12 Between them, Methody, Inst, and Victoria, the all-girls school which then had its campus halfway between them, were consciously turning out sons and daughters of the British Empire.13 It was one generation’s duty to prepare the next. In east Belfast, the late textile magnate Henry Campbell had left a bequest to found an all-boys college that bore his name. Every year, Campbell College, which operated an Officer Training Corps as part of its extracurricular activities, celebrated Empire Day, during which the head prefect would plant a tree in the school grounds, symbolizing with each passing year and each new tree the empire’s continued growth and the shelter it would provide to its obedient subjects. Its founder’s will stated that Campbell was “to be used as a College for the purpose of giving there a superior liberal Protestant education,” and flowing from all the schools that dotted the emerging or established suburbs of middle- and upper-class Belfast, there was a steady stream of young men and women who would “Fear God and serve the King.”14

Tommy Andrews had benefited from this kind of education, which inculcated Protestantism, patriotism, and propriety in almost equal measure. Like many residents of Malone in 1912, Andrews displayed the easygoing grace popularly associated with the patrician classes, but, again like Malone itself, he was in reality a product rendered in its final form by the plutocracy, the expansion of the British Empire and its Industrial Revolution. The other prominent families in Malone were, like Andrews, tied to trade. His wife, Helen, came from the Barbour family of linen merchants. The Johnstons and MacNeices had been made rich by tea; the Andrewses’ immediate neighbors, the Corrys, were in timber. The Stevensons ran Ireland’s largest printing press and its second-largest glue factory. The McDonnells, father, son, and grandson, were lawyers. Most of Maryville Park’s grand homes were occupied by Andrews’s similarly well-paid colleagues from Harland and Wolff. The former south Belfast home of Lord Deramore was now rented by the Wilsons, who had made their fortune in the property boom of the 1890s. By 1912, the aristocracy’s influence in the day-to-day life of Belfast looked set to contract to matters of taste and prestige by proxy.

It was a trend in time that had worked in the Andrewses’ favor. Tommy had learned to ride to hounds, becoming a skilled horseman and hunter, and he had played cricket at his local club—where his love of the sea earned him the nickname “the Admiral”—but despite these activities neither he nor his ancestors had ever been part of the Ascendancy.15 The family had been based in the village of Comber, eleven miles outside Belfast, since the seventeenth century, when another Thomas Andrews had established the local corn mill, which turned near their pretty house, Ardara, a product of its profits. By the time Tommy Andrews was born at Ardara in 1873, the house and its lawns had acquired a mature grace, and they were reached by an avenue lined with rhododendrons leading down to the gleaming waters of Strangford Lough.16 The Andrewses’ sustained upwards trajectory over the course of the nineteenth century had been part of Britain’s quiet revolution in local government, as the increasing complexity and size of modern bureaucracy saw power shift permanently from the hands of the landed classes to those of useful local businessmen, who became loyal politicians. Along with ownership of the mill and serving as chairman of the Belfast and County Down Railway Company, Tommy’s father was high sheriff of the county, chairman of the Down County Council, and president of the Ulster Liberal Unionist Association.17 His uncle, William Andrews, was a judge in the Irish High Court; both had been made privy councillors during the celebrations for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897.18 Tommy’s maternal uncle, Lord Pirrie, remained chairman of Harland and Wolff while being twice elected lord mayor of Belfast and elevated to the peerage for his philanthropy, and Edward VII had approved his induction into the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick, a chivalric order of knighthood once reserved for sons of the Hibernian nobility.19

Tommy’s car progressed from the quiet avenues of Malone to a city center dominated by sprawling temples to commerce. During working hours, this part of Belfast was a hive of activity, described by The Industries of Ireland as a place of “crowded rushing thoroughfares [where] we find the pulsing heart of a mighty commercial organisation, whose vitality is ever augmenting, and whose influence is already world-wide.”20 No other town in Ireland had benefited so significantly and unambiguously from the successes of the British Empire. As Britannia’s boundaries were set “wider still and wider,” Belfast had boomed and its growth seemed only to accelerate. Its population had risen seventeen-fold over the nineteenth century, with the biggest spurt occurring in the final twenty-five years, when it had doubled.21 From a town that still, in 1800, had operated as a fiefdom of the marquesses of Donegall, Belfast had, by 1900, become one of the largest urban centers in the United Kingdom, dominated and defined by its industries.22 Granted city status in 1888, a mere three years later Belfast had outstripped Dublin in terms of population and living standards.23 To celebrate, Belfast’s City Council, with the hungry and gaudy vitality of a newly enfranchised adolescent, approved the construction of a Grand Opera House, where audiences sat beneath a dome decorated with paintings of cheerfully obedient life throughout Queen Victoria’s Indian dominions as gold-leafed elephants gazed down from the front-facing corners of the proscenium arch.24

The Opera House had been part of a building mania that swept Belfast in the twenty years preceding the Titanic’s construction. The spires of the seven-year-old Protestant St. Anne’s Cathedral were visible as Tommy Andrews’s car turned right from his former school to motor down Wellington Place and pass the new City Hall, a looming quadrangle in Portland stone, with ornamental gardens, stained-glass windows, turrets, and a soaring copper dome. Completed two years after St. Anne’s, the City Hall had cost more than £350,000, a sum that had not been without controversy, especially for some of the city’s more parsimonious Presbyterians. But there were many more, including Belfast’s Chamber of Commerce, who had applauded the council’s extravagance on the grounds that a powerhouse like Belfast, “a great, wide, vigorous, prosperous, growing city,” needed to be represented with appropriate splendor.25

As a younger man, Andrews had been there to witness the surge of capitalist confidence in Belfast’s heartlands. The journey from Comber to the city was too long for the early morning starts required by the shipyards, so after he had secured his apprenticeship, aged sixteen, Andrews became a boarder in the home of a middle-aged dressmaker and her sister on Wellington Place.26 From there, he had witnessed the construction of the City Hall in the same years as Belfast inaugurated its new Customs House, a Water Office built to imitate an Italian Renaissance palazzo, and four banking headquarters.

Belfast’s Donegall Square North. Robinson and Cleaver is on the left.

Directly in front of City Hall, between its imposing entrance and its wrought-iron gates, a statue of Queen Victoria stared unseeing towards the sandstone turrets of Robinson and Cleaver, one of the most expensive and prestigious department stores in the United Kingdom. Inside the “Harrods of Ireland,” three thousand square feet of polished mirrors lined the shop’s interiors, spread over four working floors, all connected by white marble staircases, at the top of which stood statues of Britannia.27 Belfast’s well-heeled customers flocked to Robinson and Cleaver, as did prosperous members of county Society, who were prepared to pay for goods shipped “from every corner of His Majesty’s Empire.” Reflected in Robinson and Cleaver’s mirrors were busts of the store’s most august clients, including the late Lady Lily Beresford and Hariot Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, one of the bluest of the Ascendancy’s blue bloods as Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava, who had used her time in India as wife of the British Viceroy to campaign for better medical care for Indian women and introduce Robinson and Cleaver’s produce to the Maharajah of Cooch-Behar, who now also stood beside her in bust form, along with Queen Victoria’s German grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II, and his consort, Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, who had temporarily overcome her pathological hatred of Britain to place repeated orders with the firm.28 Many of the craftsmen who worked on the construction and decoration of Robinson and Cleaver, and then on the interiors of City Hall, had also labored on the ships designed by Tommy Andrews for Harland and Wolff.29 His car passed the earliest rising of these workers as they traveled on foot, by bicycle, or by tram over the bridges linking the city center to the east, Queen’s Island, and the shipyards. The majority of these dawn risers were on their way to work on Andrews’s latest and grandest creation, the Britannic, whose hull had been laid amid the driving Belfast winter rains six months earlier.30 As the journey of a million miles begins with a single step, the foundation of the largest ship built on British soil for the next two decades was already taking shape in her embryonic form. Britannic was not due to grace the waters of Belfast Lough for another two years, and her maiden voyage to New York was scheduled for the spring of 1915, at which point she would become the flagship of the White Star Line, completing the Olympic class.31

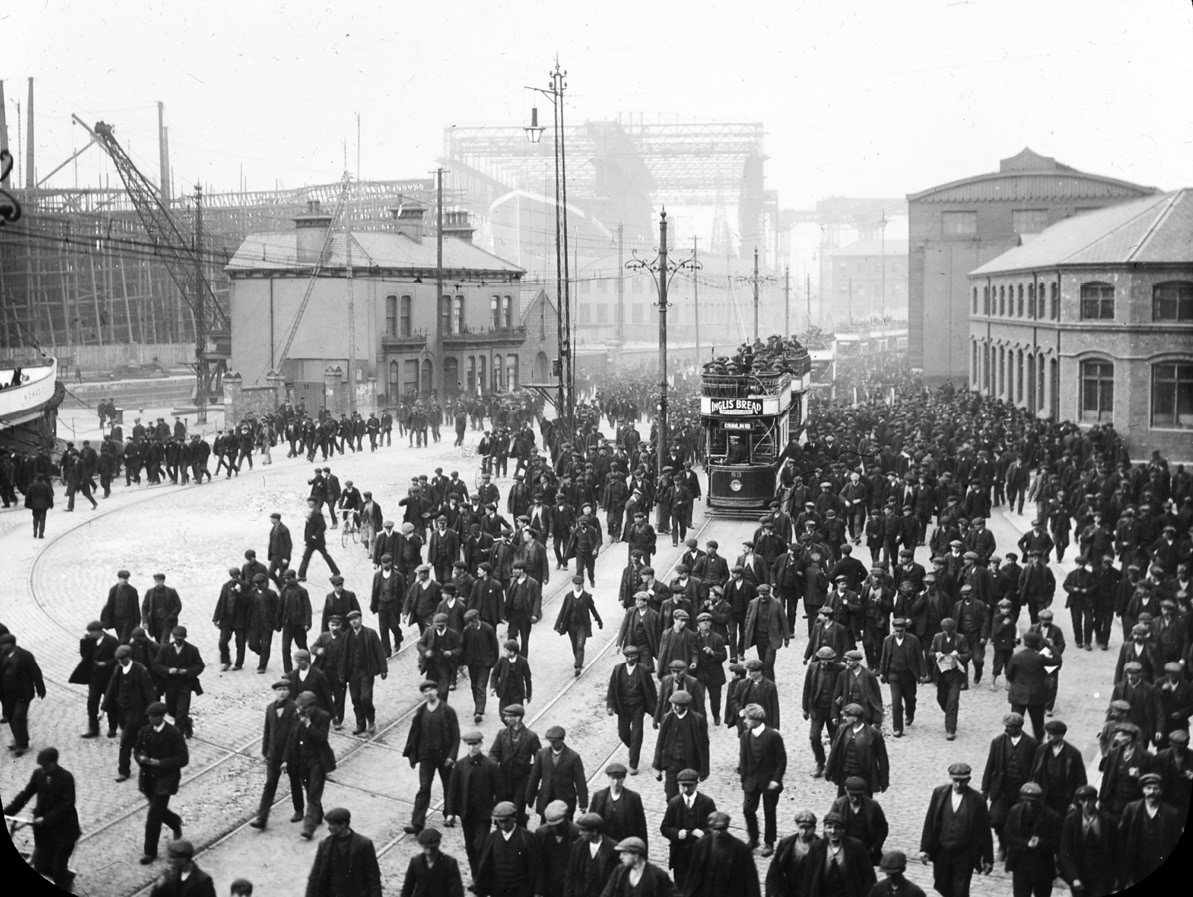

End of the day: workers from Harland and Wolff with an under-construction Titanic in the background.

The relationship with White Star Line was a source of pride to many in Belfast, which was hardly surprising considering the employment and revenue it generated, both of which were regularly cited in speeches by city officials and businessmen as among the many reasons for Belfast’s superiority over other Irish cities, a conclusion with which Andrews wholeheartedly concurred.32 Even in the very poorest parts of Belfast, all houses were single-occupancy units for families. Unlike Dublin or Cork, Belfast’s leaders had worked hard to avoid the horrors associated with the special strain of poverty bred in tenements. Alongside the thick brogue of natives, Scottish and English accents could be heard in the jostling crowds that poured from the Protestant working-class neighborhoods, their owners lured to Ulster by promises of affordable, good-quality housing through jobs at Harland and Wolff, in one of Belfast’s 192 linen manufacturers, or in its behemoth-like rope or tobacco factories.33 Belfast had one of the lowest urban rates of infant mortality in the British Empire; with eighty-two state-funded schools, it also had the highest rate of literacy for any area in Ireland, and it implemented provisions for the care of the deaf and dumb long before most other towns.34 As its two synagogues, built by the migrant turned merchant turned city mayor Sir Otto Jaffe, attested, Belfast was also so far the only section of Ireland to truly welcome and nurture a Jewish community.35 In the eyes of the loyal, all this was abundant proof that Belfast had benefited from the spirit of dynamic, self-fulfilling conservatism that guided its civic authorities and indelibly separated it—in spirit and soon, God willing, in law—from the south.36

Five years earlier, this march of progress and prosperity had been interrupted by strikes that erupted in Harland and Wolff and then spread to the adjacent dockyards. For Protestants to protest was, by 1907, an event so remarkable it shocked even seasoned observers. The dock riots erupted as work on the first of the Olympic class was due to commence. Tommy Andrews, while concerned about his timetable being disrupted, was also protective of the workers who turned his projects into a reality.37 He was appalled by some of the conditions in the yard, particularly on the gantries, where men too often fell to their deaths, lost limbs in preventable accidents, or were dismissed when they burned themselves badly on the rivets. His argument that paternalism must remedy the situation before socialism seized it had been ignored by his superiors, including his uncle Lord Pirrie, though Andrews took no pleasure in being proved right.38 At the height of the dispute, about thirty-five hundred workers were on strike, most of them organized by the charismatic trade union leader James Larkin.39 Initially, the demonstrations had looked for support from their cousins across the Irish Sea—the 1907 dock protesters voiced many left-wing sentiments, but they did so in the spirit of British social democracy, expressing implicit faith in British trade unionism, rather than Irish republicanism. However, cries of “Go back to work!” and even “Traitors!” grew louder after the strike’s opponents, aided by most of Belfast’s newspapers, painted the protest as furthering a crypto-nationalist agenda which could lethally weaken Ulster’s economy, ultimately leaving it at the mercy of the Home Rule movement. These conspiracy politics were given regrettable credibility by the behavior of certain Irish nationalist politicians, particularly west Belfast’s Joseph Devlin, who actively attempted to turn the protests into displays of anti-British sentiment.40 The strike collapsed and Larkin left Ireland, repulsed by the sight of people in working-class districts taking to their streets to celebrate the strike’s defeat. The passing years did not lessen the contempt directed at those who had betrayed the side by striking. Weeks after the Titanic’s completion, six hundred “rotten Prods” were driven from their jobs at Harland and Wolff by their own colleagues for daring to sympathize with left-wing movements that allegedly threatened the productivity of the yard and, through it, Ulster’s unchecked evolution further and further away from the agrarian economies of the southern three provinces.41 Incredibly, given its position as a major industrial city, there was no serious interest in trade unionism from Belfast for another twenty years. It was seen as somehow disloyal, destructive of the greater good. Nor were the six hundred rotten Prods of 1912 expelled alone. At the same time, a sectarian pogrom in employment forced the shipyard’s twenty-four hundred Catholic employees to quit.42

Belfast’s growth was as remarkable as it was undeniable, but to pretend that the fruits of that progress were evenly distributed is absurd. There were no laws in Edwardian Ulster that mandated discrimination against the province’s Catholic minority, but equally there were none to stop it, and this left Protestants free to hire those of their own preference, who were, overwhelmingly, their coreligionists. Protestant jobs were often marginally better paid and nearly always significantly more secure than a northern Catholic’s. As the Home Rule crisis accelerated, so too did Protestants’ antipathy towards their Catholic neighbors, resulting in appalling events like the aforementioned expulsion of thousands from their jobs at Harland and Wolff. Belfast’s reputation for anti-Catholic discrimination was so widespread that San Francisco’s civic authorities refused to name one of their streets in the city’s honor, despite a petition from Ulster-born immigrants.43

From the route Andrews’s car took, just visible on the horizon was the spire of the Church of the Most Holy Redeemer, another product of the construction bonanza, but one which a man like Tommy would likely never see save from a distance. Located in west Belfast, Holy Redeemer was described at the time of its completion as “a noble Church in the most Catholic quarter of a bitterly Protestant city.”44 The two communities’ decisions to congregate themselves into working-class neighborhoods in the west and east was a prophylactic kind of social engineering, which, like all such things, had the potential to fail.

Religion gave a toxic, defining flavor to this political quarrel. It was true, as many in the north of Ireland so strenuously insisted, that the troubles of their region were not caused by religion, in so far as no one ever rioted in defense of consubstantiation or tossed a brick over whether there are seven sacraments or two. But that is to miss the point, in that religious affiliation defined the boundaries of division. Although it was not universally true, overwhelmingly Protestants favored retaining union with Britain, while Catholics hoped for the opposite. The years preceding the Titanic’s construction had witnessed an intensification of this trend. A series of mid- and late-nineteenth-century evangelical missions into the working-class areas of Belfast had deliberately solidified a view of Catholicism as backwards, tyrannical, and superstitious.45 Just as they pointedly began to eschew the adjective “Irish” in favor of “northern Irish” or simply “British,” many of the more zealous Ulster Protestants began to redefine the etymology of the word “Christian” to mean axiomatically, and solely, “Protestant.” When a Catholic converted to Protestantism, the phrase “He has become a Christian” was launched with depressing frequency. Meanwhile, the Gaelic Revival, a rejuvenated and sustained interest in the Celtic culture of Ireland, created a series of societies that defined being Irish in opposition to that which was British, all the way down to what sports should be played.46 Some of these groups made an effort to reach out to Irish Protestants, but others made an effort to do the exact opposite by helping “to embed the myth that Ireland was a religiously and ethnically homogeneous society.”47 This idea that to be Irish meant being Catholic played into the hands of unionists in the north who claimed that a compromise with Home Rule would be tantamount to collective suicide, particularly since unionists insisted that the moderate proposals for Home Rule would inevitably result in full independence. The nineteenth century’s torturous preoccupation with race birthed apparently “scientific” justification of each side’s respective prejudice; the “Two Nations Theory” insisted that there were insuperable racial, moral, cultural, and intellectual differences between Irish Catholics and Protestants. Even academic publications like the Ulster Journal of Archaeology promulgated the idea that Irish Protestants, particularly those in the north, were essentially Anglo-Saxon, while Irish Catholics were predominantly Celtic, giving both a distinct set of characteristics which made political union between them an absurdity. Protestants were hardworking, law-abiding, and stalwart; Catholics, as Celts, were lazy, dishonest, and prone to drunkenness. Nationalists often accepted this racial hogwash, but rejigged it to class Hibernian Catholics as hospitable, artistic, and passionate, while Protestants were dour, miserly, and cruel.48

By the time the Titanic had been completed, the question of Irish independence, whether in part or in full, was the blood seeping beneath a closed door in Belfast. Fear of it preoccupied everybody, including Thomas Andrews. In his own political views, Andrews was described by family friends as “an Imperialist, loving peace and consequently in favour of an unchallengeable Navy. He was a firm Unionist, being convinced that Home Rule would spell financial ruin to Ireland.” However, he was uneasy with the perceptible drift towards Irish politics being governed by “passion rather than by means of reasoned argument.”49 Many Ulster Protestants sincerely believed, and were proved correct in their suspicions, that Irish independence would constitute a major triumph for Catholicism in the island, with an Irish government choosing to grant special status to the Catholic faith.50 Ironically, the north’s fevered insistence on absenting itself from independence was the behavior of Laius after the Oracle since Ulster’s secession would mean the removal of the majority of Irish Protestants from a future Irish state, whatever the strength of that state’s ties to Britain, thus enabling many of the events they claimed to fear. As a southern lawyer practicing in Belfast tried in vain to warn his unionist friends, if the predominantly Protestant north separated from the predominantly Catholic south, “you would have not one, but two, oppressed minorities.”51

Protestant fears of being outnumbered and thus overruled by their Catholic compatriots were lent unfortunate credence by Pope Pius X’s issuing of the Ne Temere decree of 1907. The decree ruled that any marriage between a Catholic and a Protestant was invalid unless it was witnessed by a priest, implicit within that stipulation and often explicit in its application being a priest’s refusal to officiate unless an undertaking was given that any children born to that couple were raised Catholic. Ne Temere seemed particularly unhelpful in the Irish context because it negated a papal rescript, issued by Pius VI in 1785, which had allowed for the legality of mixed marriages in Ireland, even if they were not solemnized before a Catholic priest.52 Viewed as pastoral care by its defenders and lambasted by critics as prejudice by stealth, Ne Temere resulted four years later in the McCann case, when the marriage between a Belfast resident called Alexander McCann, a Catholic, and his Protestant wife, Agnes, fell apart. A private sorrow became a public circus when McCann’s local priest allegedly encouraged the separation and certainly helped Mr. McCann gain sole custody of his children, despite the fact that the McCanns had married before the publication of Ne Temere. Agnes McCann went to her local minister, Reverend William Corkey, who had already regularly waxed apoplectic in his sermons about the “foul” Ne Temere decree and saw in the McCann case the inevitable fruition of Pius X’s edict.53 As such things often did in Edwardian Belfast, the issue moved from the pulpit to the press to protests, the latter of which spread from Belfast to London, Dublin and Glasgow.54 At one rally, the McCanns’ marriage certificate was held up before the crowd, as a Presbyterian clergyman roared, “I hold in my hand a marriage certificate bearing the seal of the British Empire, and recording the marriage of Alexander McCann and Agnes Jane Barclay. This certificate declares that according to the law of Britain these two are husband and wife. This Papal decree says their marriage is ‘no marriage at all.’ Which law is going to be supreme in Great Britain?”55 The pursuit of the answer had already fractured lifelong friendships, and it looked, in 1912, as if it had the potential to destabilize an empire.

As he boarded the Titanic, Andrews received a note from one of his colleagues informing him that there was a problem in one of the boiler rooms. Since this was their first full run, that was to be expected. A fire had started raging when some of the coal stored in one of the bunkers had caught fire and there was no chance of putting it out before the ship was due to start her tests. Should they postpone them? No, not if the fire in question could be contained. An extra squadron of stokers and firemen was deployed to monitor the troubled boiler room, the others were fired up, and, without fanfare, the Titanic took to the ocean for the first time, beginning six hours of technical maneuvers and trials.

The sea trial had originally been scheduled for the previous day, but was postponed in the face of high winds which would have made it impossible to vet properly the Titanic’s speed and her turning and stopping capabilities in calm seas. The winds had since died down, allowing for the leviathan to undertake maneuvers which saw her tested at a variety of speeds, ranging from 11 to 21½ knots, the latter being close to her expected full speed. She was also halted at 18 knots, coming to a stop three minutes and fifteen seconds later, at just three and a half times her own length, which, for a ship of her size traveling at that velocity, was judged yet another encouraging indicator of her safety.56 On board, Andrews meticulously watched each maneuver, joined by some of the colleagues who knew the ship almost as well as he did, chief among them Francis Carruthers, the British Board of Trade’s on-site surveyor, and Edward Wilding, the yard’s senior naval architect. As the Board’s eyes at Harland and Wolff, Carruthers had made hundreds of trips to the Titanic over the course of her construction. Wilding, like Carruthers an Englishman who had relocated to Ireland for his job, was not just a colleague but a friend, who had been a guest at Andrews’s wedding in 1910. Together, the three men had watched Titanic’s “vast shape slowly assuming [her] beauty and symmetry.” She was, thus far, the crowning glory of Andrews’s and Wilding’s careers, “an evolution rather than a creation,” according to one of their contemporaries, “triumphant product of numberless experiments, a perfection embodying who knows what endeavour, from this a little, from that a little more, of human brain and hand and imagination.”57

The Titanic in Belfast Lough during her sea trials.

On her way back into Belfast, Titanic passed the seaside town of middle-class Holywood on one side of the Belfast Lough and working-class Carrickfergus on the other. In both towns, it was time for local chapters of the Orange Order to be out on the streets practicing their music, hymns, and configurations in preparation for the start of marching season, an annual series of parades held to commemorate the anniversary of King William III’s victory over his Catholic uncle at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 and the ensuing establishment of a legal Protestant ascendancy in Ireland for the next century. The Orange Order, founded as that ascendancy had cracked open in defeat at the end of the eighteenth century, organized itself somewhere between masonic and military lines, claiming nearly one-third of northern Protestant men as members.58 Each was required, by oath, to “love, uphold, and defend the Protestant religion, and sincerely desire and endeavour to propagate its doctrines and precepts [and] strenuously oppose and protest against the errors and doctrines of the Church of Rome; he should, by all lawful means, resist the ascendancy of that church.” A later extension to the formula, added in 1860, prohibited members from ever attending a Roman Catholic religious service.II59

Disruption, intimidation, and violence at Order events had resulted in legislation curtailing its parades in the middle of the nineteenth century, and its reputation for disruptiveness had lasted, even among many Protestants, until the 1870s.60 By 1912, however, its influence in the north of Ireland was enormous. Even politicians and clergymen who were indifferent or hostile to the Order’s aims, like the MP Sir Edward Carson, who privately compared it to an ancient Egyptian mummy, a preserved and desiccated corpse of something that had mattered long ago, “all old bones and rotten rags,” felt that they had to join if they stood any chance of appealing to working-class voters.61 Andrews and his brothers came from a family with a long association with the Order who marched with its orange sashes around their necks, every year.62 Andrews would be back in Belfast by the time of the Order’s parades at the high point of marching season, July 12.III Each lodge had their own banner, depicting a vividly rendered moment in Irish Protestant history—a particular favorite was an image of drowning settlers, usually women and children, piously clutching a cross as they were butchered, with the slogan “My Faith Looks Up to Thee,” victims of anti-Protestant massacres carried out in 1641. On the reverse of all banners, long-dead King William forded the waters of the Boyne River atop his white steed, his sword already drawn for the children of the Glorious Revolution and their descendants, who would defend its legacy. As the Order’s most famous song proclaimed:

For those brave men who crossed the Boyne have not fought or died in vain,

Our Unity, Religion, Laws, and Freedom to maintain,

If the call should come we’ll follow the drum, and cross that river once more

That tomorrow’s Ulsterman may wear the sash my father wore!

By April 1912, the Order had helped rebrand Home Rule as “Rome Rule.” On the day the Titanic conducted her trials, a letter to the Belfast News-Letter from a local headmaster opined, “Under Rome Rule, there is no possible future for unionists, but despairing servitude or its preferable alternative—annihilation.”63 Hysteria had trumped civic virtues. Rome was on the march. Upper-class Protestants had forgotten their fears of the radicalized workers and had instead given themselves over to the giddy novelty of Protestants straining together in common cause, as they had in days of old—or so the banners of the Orange Order told them. A paramilitary organization, the Ulster Volunteer Force, was formed, with thousands of recruits training on aristocratic estates as guns were smuggled into the island to arm them. One of Andrews’s compatriots wrote with moist-eyed pride that it was “indeed a wonderful time. Every county had its organisation; every down and district had its own corps. The young manhood of Ulster had enlisted and gone into training. Men of all ranks and occupations met together, in the evenings, for drill. This resulted in a great comradeship. Barriers of class were broken down or forgotten entirely. Protestant Ulster had become a fellowship.”64

The sound of these flute-serenaded battle cries followed the Titanic in and out of her home waters. She was born in this heartland of an industrial miracle, with its rich and explosive confusion. We might look back now and think it unutterably bizarre that Ulster was prepared to immolate itself to prevent a quasi-independence that might never have matured to full secession if the north had chosen to be a part of it, but to the participants in this quarrel they were contenders in a Manichean struggle for the very soul of Ireland. In London, the new king was frantically trying to organize a preventative peace conference at Buckingham Palace, hopeful of exploiting unionism’s atavistic attachment to the Crown to force its adherents back into line, and three days before the Titanic left Belfast the constitutional nationalist Sir John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, gave a speech in Dublin, squarely aimed at his compatriots in the north—“We have not one word of reproach or one word of bitter feeling,” he promised. “We have one feeling in our hearts, and this is an earnest longing for the arrival of the day of reconciliation.”65

No one was listening. It was a man of action who flourished in April 1912, drowning out men of prudence. Unionism was now dominated by leaders like the lawyer Edward Carson, who had once served as the prosecuting counsel against Oscar Wilde, and the Andrewses’ family friend, the ferociously uncompromising Sir James Craig. To make explicit how far they were prepared to go if Home Rule was extended to Ulster, the Ulster Volunteer Force, the Orange Order, and the heads of the north’s major industries were organizing one of the largest mobilizations of political sentiment in Irish history, a covenant due to be paraded through the province to an enormous final rally outside Belfast City Hall.66 Agents were sent out to help those in the smaller towns and countryside who wanted to sign. Tommy Andrews and the men in his family intended to sign this declaration:

Being convinced in our consciences that Home Rule would be disastrous to the material well-being of Ulster as well as of the whole of Ireland, subversive to our civil and religious freedom, destructive of our citizenship, and perilous to the unity of the Empire, we, whose names are underwritten, men of Ulster, loyal subjects of His Gracious Majesty King George V., humbly relying on God whom our fathers in days of stress and trial confidently trusted, do hereby pledge ourselves in solemn Covenant, throughout this our time of threatened calamity, to stand by one another in defending, for ourselves and our children, our cherished position of equal citizenship in the United Kingdom, and in using all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland. And in the event of such a Parliament being forced upon us, we further solemnly and mutually pledge ourselves to refuse to recognise its authority. In sure confidence that God will defend the right…67

Partly from despair and frustration that unionism would never willingly give so much as an inch in compromise, and partly in tune with the mounting radicalization of nationalist politics across Europe, Irish nationalism was evolving and splitting into republicanism, itself increasingly shaped by diehards like Pádraig Pearse. Moderation had become a tarnished virtue, a tired or even pathetic concept. Although he begged his followers to “restrain the hotheads,” Edward Carson simultaneously urged them to “prepare for the worst and hope for the best. For God and Ulster! God Save the King!”68 On the other side of the soon actualized barricades, Pearse urged his followers to hope for civil war, to pray for rebellion, and for all of British Ireland to vanish in flames regardless of the human cost, because “blood is a cleansing and sanctifying thing, and the nation that regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood.”69 From their respective demagogues, all sides in Ireland heard the sibyl cry of their pasts, promising them the future glory of a war without ambiguity. Protestant and Catholic, loyalist and nationalist, Ireland would willingly wrestle itself off a cliff edge, plunging the entire island into the unknown. The head of the police service, the Royal Irish Constabulary, told the Chief Secretary of Ireland, “I am convinced that there will be serious loss of life and wholesale destruction of property in Belfast on the passing of the Home Rule bill.”70

When he arrived back in Belfast that night, after the sea trials, Andrews sent a note to his wife in Malone. Everything had gone well; there were one or two problems, which would no doubt be fixed by the time the ship reached Southampton three days later. Francis Carruthers had been duly satisfied by the Titanic’s performance and he had granted her the Board of Trade’s standard twelve-month certificate as a passenger ship.71 Andrews and Wilding spent the night on board, to prepare for the early morning departure to England. The Union Jack fluttered from one of the Titanic’s flagpoles as the sun set around the slumbering leviathan with the fire burning unchecked within her interiors.

I. Created as the earldom of Donegall by Charles I in 1647 and elevated to a marquessate by George III in 1791, the title retains the antique spelling of “Donegall,” though the county itself is usually spelled “Donegal” in English today. The heir uses the courtesy title of Earl of Belfast.

II. At the time of writing, these injunctions remain in place.

III. This is sometimes colloquially known as “the Glorious Twelfth” in the north of Ireland, although the term originally applied to the start of the grouse-shooting season for the landed classes on August 12. Whether the appropriation of this nickname for July 12 originated as a joke or a mistake is unclear.