CHAPTER 3 Southampton

[The Titanic] was so much larger than one even expected; she looked so solidly constructed, as one knew she must be, and her interior arrangements and appointments were so palatial that one forgot now and then that she was a ship at all. She seemed to be a spacious regal home of princes.

Ernest Townley, interview given to the Daily Express (April 16, 1912)

ONE WEEK AFTER HER MIDNIGHT arrival at Southampton, the Titanic’s main mast ran the company’s red flag with its eponymous white star, fluttering over final preparations for her first commercial voyage.1 The day of departure, Wednesday, April 10, was overcast in the south of England, with the sun occasionally appearing from behind the scudding clouds to provide a mild temperature of about forty-eight degrees Fahrenheit as the crew, numbering about nine hundred, were divided into three groups for the muster. Firemen, seamen, and those assigned to care for the soon-to-board passengers went through their final medical checks and a head count, carried out under the watchful eye of another representative of the Board of Trade, who then proceeded to observe as two of the ship’s twenty lifeboats were lowered down the side with eight trained crew wearing their life jackets. Typically, this inspection would involve the tested lifeboats unfurling their sails, but an uncooperative breeze put pay to that, so the white-painted wooden craft were successfully raised back onto the deck and into their davits with their virgin sails left unfurled. Vast quantities of luggage were being maneuvered on board. Pieces bound for the first-class quarters bore White Star–provided labels with variants of CABIN or STATEROOM, to indicate that they should be taken to the passenger’s bedroom; BAGGAGE ROOM or WANTED, if they were not to go immediately to their accommodation but contained items which might be required later in the voyage, a helpful utilization of space given the upper classes’ minimum requirement of three outfit changes daily; and NOT WANTED, if the pieces were to go into the hold until disembarking.2

Thomas Andrews had arrived on board half an hour or so after dawn that morning, checking out from his interim accommodation at the nearby South-Western Hotel, where he had stayed in the week since leaving Belfast.3 The days in between had been spent overseeing the last touches to the Titanic’s accommodation, which produced the kind of productive mania at which Andrews excelled. The ship’s schedule had already been altered, and then squeezed, by her elder sister’s accident in the Southampton waters a few months earlier when, moments after departure, the Olympic had collided with the British warship Hawke.4 Mercifully, there had been no serious injuries, but a trip to Belfast for repairs was required, with the result that construction on the Titanic temporarily halted for a few days, tightening the preparation time allowed for the maiden voyage. Andrews himself did not doubt that “the ship will clean up all right before sailing on Wednesday,” but with the door hinges and paint still being applied to the Titanic’s Parisian-style café on Wednesday morning, White Star had ordered in vast quantities of fresh flowers which went straight into the Titanic’s cold storage to be brought out over the course of the voyage to disguise any lingering smell of varnish.5 Fixtures in some of the second-class lavatories needed to be attached, furniture bought from firms in England had to be delivered, the furniture in the Café Parisian still was not the right shade of green, and the pebble dashing in two of First Class’s most expensive private suites was too dark.6 Andrews had overseen everything he could. His secretary, Thompson Hamilton, who had joined him from Belfast for the week, noticed, “He would himself put in their place such things as racks, tables, chairs, berth ladders, electric fans, saying that except he saw everything right he could not be satisfied.”7 Meanwhile, a hose was working away on the contained fire in one of Boiler Room 5’s coal bunkers, with the source expected to be extinguished in the next few days.8 By the evening of the 9th, everything of note had apparently been taken care of and Andrews could write to his wife, “The Titanic is now about complete and will I think do the old Firm credit to-morrow when we sail.”9

With their tasks accomplished, Andrews said a temporary farewell to colleagues, like Edward Wilding, whose work on the Titanic ended in Southampton, and Thompson Hamilton, who was traveling back to Belfast to handle any correspondence during Andrews’s absence. “Remember now,” Andrews told his secretary, with that second word ubiquitous to an Ulster dialect, “and keep Mrs. Andrews informed of any news of the vessel.”10 From the deck, Andrews could see other ships, moored together in greater numbers than usual. The British Miners’ Federation had voted to end a six-week strike only four days earlier, and the impact on an industry as dependent on coal as shipping had been temporarily significant—many smaller liners had their voyages rescheduled to facilitate coal being reallocated for the on-time departures of the leviathans.11 The red-white-and-blue-capped funnels of the American Line’s St. Louis, Philadelphia, and New York were moored next to White Star’s Majestic and Oceanic. After twenty-two years at sea, the Majestic had been withdrawn from regular service and designated a reserve ship, while the Philadelphia and the New York were about to have their first-class quarters removed entirely for an increase of Second and Third Class, as the drift of first-class clientele to larger, more modern ships had rendered them superfluous.12 For Andrews, the most significant of the slumbering ships in the harbor was White Star’s former flagship, the Oceanic, berthed alongside the New York. After working his way up from his post-school apprenticeship at Harland and Wolff, Andrews had first been attached to a design for the White Star Line in the late 1890s, helping to produce the Oceanic, praised then and later as a “ship of outstanding elegance both inside and out.”13 The Oceanic was still in service in April 1912, but shipbuilding’s technological strides in the thirteen years since her debut had left that pretty ship far behind; the Titanic was nearly three times heavier than Andrews’s first ship, with room for almost twice as many passengers and crew.

Far below, the process of boarding the third-class passengers began shortly after the crew’s muster was completed. Since many in Third Class traveled as emigrating families, there were usually more children, necessitating a longer boarding process, combined with the delay-inducing medical inspections required by American immigration authorities.14 Those on the dock that day were a few hundred of the 23,000 immigrants who would sail on White Star ships to America over the course of 1912–13.15 Although it was, and is, often used to describe this collective, the word “steerage” did not properly apply to those in the Titanic’s Third Class. The noun sprang from the earlier days of mass migration to the United States, and it could still in 1912 apply to the cheaper class of accommodation offered by other, often less prestigious travel companies, but there was an appreciable difference. Hamburg-Amerika’s soon to be launched Imperator would provide four classes of travel, delineating Third and Steerage as two different sections of the ship.16 To qualify as steerage, there had to be communal dormitories, something that the Titanic did not offer. Every third-class passenger was in a cabin, albeit with bunk beds and, if the passenger was traveling alone, typically shared with others of the same gender. The White Star Line had a reputation for offering the best third-class accommodation then available, with the result that tickets on the Titanic or the Olympic could cost as much as Second Class on other liners.17 Thus a contemporary travel guide could confidently assert that the White Star Line carried “a better class of emigrant.”18

Nonetheless, following a cholera epidemic among immigrants at the German port of Hamburg twenty years earlier, the United States had introduced firm policies on who could be admitted at Ellis Island.19 This meant that all third-class passengers had to undergo medical examinations at embarkation and that there could be no contact between them and the two more expensive classes, because if there was, those passengers would also have to be inspected before leaving the ship in New York.20 For first- and second-class passengers this meant that barring any glances from their promenade decks down to the outdoor areas at the stern for Third Class, boarding was likely to be the only time they had a sustained opportunity to see third-class passengers. Even leaving aside the quarantine issues set by the American government, contemporary travel guides insisted that it was the height of bad manners for a first-class passenger to play the tourist by asking to see the third-class public rooms during the voyage: “It cannot be urged too strongly that it is a gross breach of the etiquette of the sea life, and a shocking exhibition of bad manners and low inquisitiveness, for passengers to visit unasked the quarters of an inferior class… the third-class passengers would be within their rights in objecting to their presence… they expect to have the privileges and privacy of their quarters respected also.”21

Unlike the tickets held by passengers who could afford to cross the ocean annually or travel far and wide for their holidays, a third-class ticket was usually a one-way experience, a fact which produced particularly heartrending scenes on the dock. While viewing the boarding process of another of the “floating palaces” in 1912, the contemporary travel writer R. A. Fletcher asked one of the crew for the reasons behind a much longer embarkation window for Third Class, which the latter explained had something to do with how often immigrants ran back across the gangplank to embrace loved ones who had come to wave them off. “It’s a nuisance, you know,” the crew member remarked,

when you want to be off, but after all its [sic] human nature and you can’t blame them. If I were a woman I’d be as bad myself. You see, it comes harder to a married woman to pull up stakes and to make a new home in a new country than it does to a man or children. A man makes a new home and the children grow up in new surroundings and become accustomed to them; but God help most of the mothers. They go for the sake of husbands and children, but they leave their hearts behind them, in another sense, as often as not.22

For the Countess of Rothes, the purpose of her transatlantic jaunt was also for the sake of her husband, albeit in happier and less permanent circumstances. The Earl had been in the United States since February, when he had sailed from Liverpool on the Lusitania, to go on a fact-finding mission, comparing the efficiency of the privately operated American telegraph system with that of its publicly owned British equivalent. After his work was finished, Norman took the opportunity to tour, and he had invited Noëlle to join him in the United States to celebrate their twelfth wedding anniversary with a visit that would culminate with a stay in a rented cottage on an orange grove in Pasadena, California, one of the properties Norman was allegedly interested in purchasing.23

Trading the inconsistent loveliness of an English spring for the beautiful monotony of California’s had not presented Lady Rothes with an easy task when it came to packing. She had been piecing together a new wardrobe for her American sojourn up until the day before she left London, including a last-minute dash to Zyrot et Cie, a milliner’s near her townhouse on Hanover Square, where she picked out some new hats and motoring veils.24 Most of those would go into one of the two steamer trunks that Noëlle would not need during the voyage, sequestered in the cavernous chill of the hold until they reached Manhattan. London was wrapped in its own brand of unseasonable frigidity, with the result that most of Noëlle’s fellow passengers had boarded the train that morning wearing top coats and hats.25

Noëlle was boarding en famille in a traveling cabal held together by affection, vaguely complementing itineraries, and curiosity about the Titanic. Her companion as far as New York was her husband’s cousin Gladys, a vivacious and unmarried fixture of the London social scene who had decided to keep Noëlle company for the voyage and visit her brother, Charles Cherry, an aspiring theater actor who had moved to New York two years earlier. Gladys and Noëlle were friends and, following the convention of most families at the time, referred to each other as “my cousin” after Noëlle and Norman’s marriage. They were joined by Noëlle’s parents, Clementina and Thomas Dyer-Edwardes. Thomas had taken long voyages before—indeed, arguably one of the longest possible when he had sailed from England to Australia in the 1860s to spend ten years increasing the family’s fortune—but this trip on the Titanic was not to add to the roster of his far-flung travels. He and Clementina were only going as far as the Titanic’s first port of call, the town of Cherbourg in northwestern France. From there, they would travel to Château de Rétival, their eighteenth-century house in Normandy, which they were opening up for the summer. Since they usually made the first annual trip to expel Rétival’s dustcovers in spring, the Dyer-Edwardeses had decided to combine their cross-Channel trip with Noëlle’s departure for America. It would be a chance to wish their only child Godspeed before she was gone for several months, with the added attraction of traveling, however briefly, on the inaugural voyage of the world’s largest liner. There seems to have been a slight delay with the boat train from Waterloo, which did not reach Southampton until about eleven thirty, thirty minutes before the ship’s scheduled departure.26

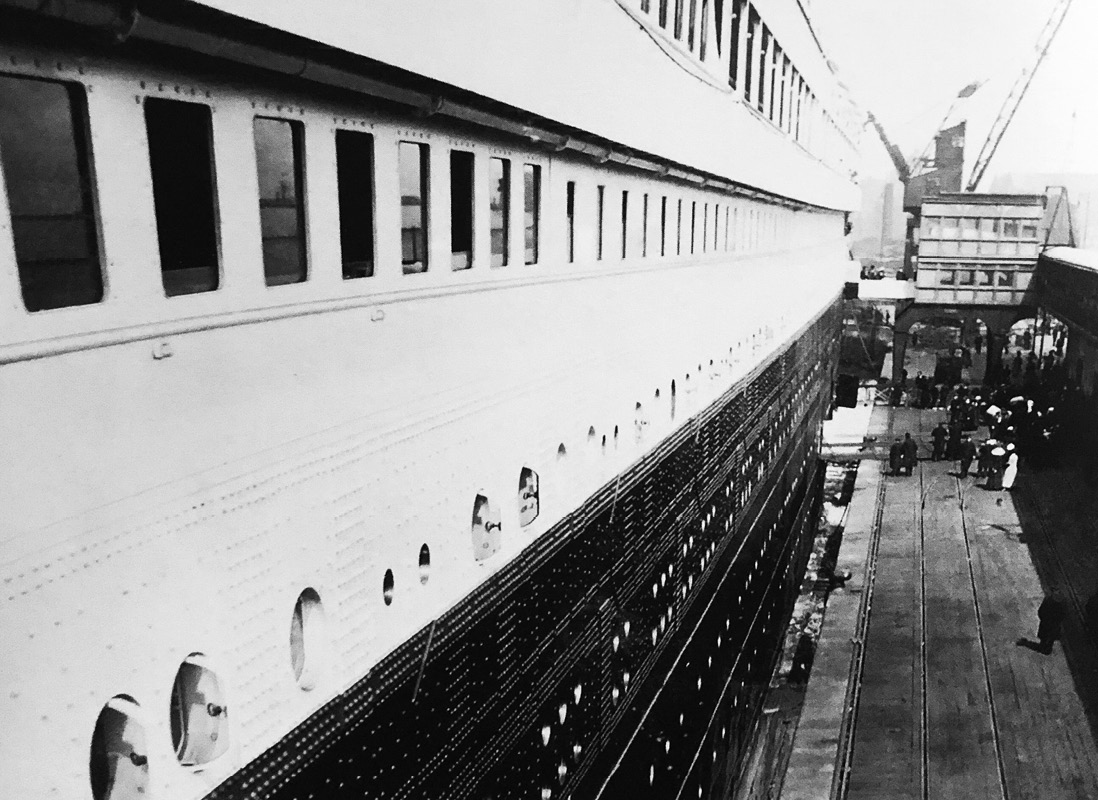

When the train came to a halt on tracks running parallel to the Titanic’s towering hull, the Countess’s party stepped out into a large shed, nearly seven hundred feet in length, where a small, industrious army of porters were dealing with the last of the ship’s cargo and luggage.27 Noëlle’s steamer trunks were added to their task as she, her parents, and Gladys and Noëlle’s lady’s maid, Cissy Maioni, crossed under the skylights and up the stairs to an enclosed balcony, where they presented their tickets.28 They were ushered over the twenty-eight feet of the gangplank, from which, turning right, they could see the second-class walkway, on the same level but five hundred or so feet aft, and one of the third-class gangways, three decks below.

The view from the first-class gangplank on departure day. Those used by Second (ABOVE) and Third Class (BELOW) can be seen in the distance.

They arrived to see crew members waiting for them in a white-paneled vestibule with a black-and-white-patterned floor, which had such a gleaming finish that some passengers initially mistook it for marble.29 Several of the Titanic’s officers were required to be on meet-and-greet duty for the first-class passengers, a piece of etiquette that had survived in transmogrified form from the days of sail when the owners of ships had often escorted prominent passengers on board themselves.30 However, it was the stewards and stewardesses, not the officers, who offered practical help by escorting the passengers to their rooms. Since they were only going as far as France, Noëlle’s parents had a ticket that entitled them to lunch and afternoon tea, but no cabin. Noëlle herself and Gladys were to spend six or seven nights as roommates in cabin C-37.31

The Titanic’s decks were labeled with alphabetical efficiency. Unlike many other liners, where decks were often given a name indicating their purpose, like “Shelter,” “Saloon,” or “Upper,” the Titanic’s top deck, which was open to the elements and housed her lifeboats, was called the “Boat Deck,” but after that her levels were ranked in consecutive descent from A- through to G-Deck, the final point accessible to passengers, below which were the boiler and engine rooms.32 A common misconception about the allocation of space for the respective traveler classes was that the liners’ architecture directly replicated the concept of social hierarchy, with First Class occupying the top decks and Third spread over the lowest. In reality, the most stable parts of a liner are amidships, since they are the least prone to pitching during inclement weather. On the Titanic, First and Second Class were located amidships, running downward through the ship and linked for the crew by various corridors. Both classes had access to the air on the Boat Deck, with a low dividing rail separating Second Class’s aft promenade from First’s more expansive, forward-facing space. First-class cabins, generally referred to by the slightly grander adjective of “stateroom,” ran from A- to E-Deck, while the public rooms were dotted around, from the Gymnasium, through a door off the Boat Deck, to the Swimming Pool, Squash Court, and Turkish Baths down on F-Deck. Their public rooms generally lay on either side of the two sets of staircases, one forward and one aft, running through every level of first-class accommodation. The space between the staircases was connected by the stateroom corridors.

Every passenger with a first-class ticket had access to the same amenities and food included in the tariff, but there were significant gradations of luxury and corresponding cost when it came to the staterooms. The most expensive single class of ticket on the Titanic, one of the two suites with their own private verandas, was located on B-Deck, and it was on B- and C-Deck that the ship’s most lavish accommodation was located. The only noticeable difference between the two decks’ staterooms was their windows—B-Deck was the lowest level of the Titanic’s white-painted superstructure, enabling her cabins and suites to offer rectangular windows. Immediately below and also painted white, C-Deck was the highest deck in the Titanic’s otherwise black hull; all cabin windows in the hull were the more traditional nautical portholes.

At Southampton, the Countess of Rothes and the other first-class travelers boarded straight onto B-Deck and, having confirmed their cabin numbers, were escorted by stewards from the vestibule, immediately turning right. They would then either have walked down the stairs or, less probably given how short the distance was, taken one of the three elevators to C-Deck. It was possible for first-class passengers traveling with their own servants, as Noëlle was with Cissy Maioni, to book them into cabins in Second Class, but Noëlle had evidently decided that that was rather mean-spirited, with the result that Cissy was to occupy a first-class cabin of her own, two levels below, on E-Deck.33

Between the train and the gangplank, the Countess had been asked for a comment by the English correspondent of a foreign gossip column, who wanted to know what the doyenne of the beau monde felt about “leaving London Society for a California fruit farm.” With her imperturbable no-nonsense cheer, the Countess had smiled back, “I am full of joyful expectation.”34 Unfortunately, joyful expectation experienced its first stutter when the door to C-37 was opened for them. The Titanic’s surviving deck plans give several possible reasons for Noëlle’s request to be moved—the first being C-37’s location so close to the stairwell and elevators. It was located in the corridor immediately leading off from them, which may have made Noëlle worry unnecessarily about possible noise and disturbance. There was also the issue of C-37’s size, which offered comfortable if standard first-class accommodation, different from the more splendid options profiled in the White Star Line’s advertising.35 It has been suggested that Lady Rothes’s parents decided to treat their daughter and her companion to an upgrade; it has also been suggested that the room was unsuitable for the Countess. The two explanations are not wholly contradictory. The Purser’s Office was on the same deck and requests to be moved were not uncommon. An admiring captain with the Cunard Line thought that pursers and their staff on board the great liners “do most of the clerical work of this floating city; the purser’s office is a kind of ‘enquire within’ bureau for passengers; it is a reception office; it is the place where complaints are ventilated, and where official oil is poured on the sometimes troubled waters that are bound to occur in a ship that carries, as she often does, thirty different nationalities—including people of widely different tastes, customs, temperaments and requirements.”36 Upon hearing that the request for a new room concerned Lady Rothes, Purser McElroy seems to have moved with breakneck speed.

They were escorted past the staircase, the Purser’s Office and its Enquiry Desk, which functioned much like the lobby of a modern hotel, and into long white-paneled corridors leading to stateroom C-77. It was a particularly convenient relocation for Cissy, since her employer’s new room was opposite the small but comfortable special dining room set aside for maids, valets, and other servants traveling with their employers.37 Lady Rothes was, by European standards, the highest-ranking person on the ship, a silken-voiced embodiment of the empire of manners which the British aristocracy still commanded. With her caste’s social influence still tangible, Noëlle was not an anachronism on the Titanic, but she was an anomaly in being the only member of the nobility on board.38 An old world silently passed a new one as the Countess’s party walked among the self-made millionaires and plutocrats who occupied most of the other C-Deck staterooms.

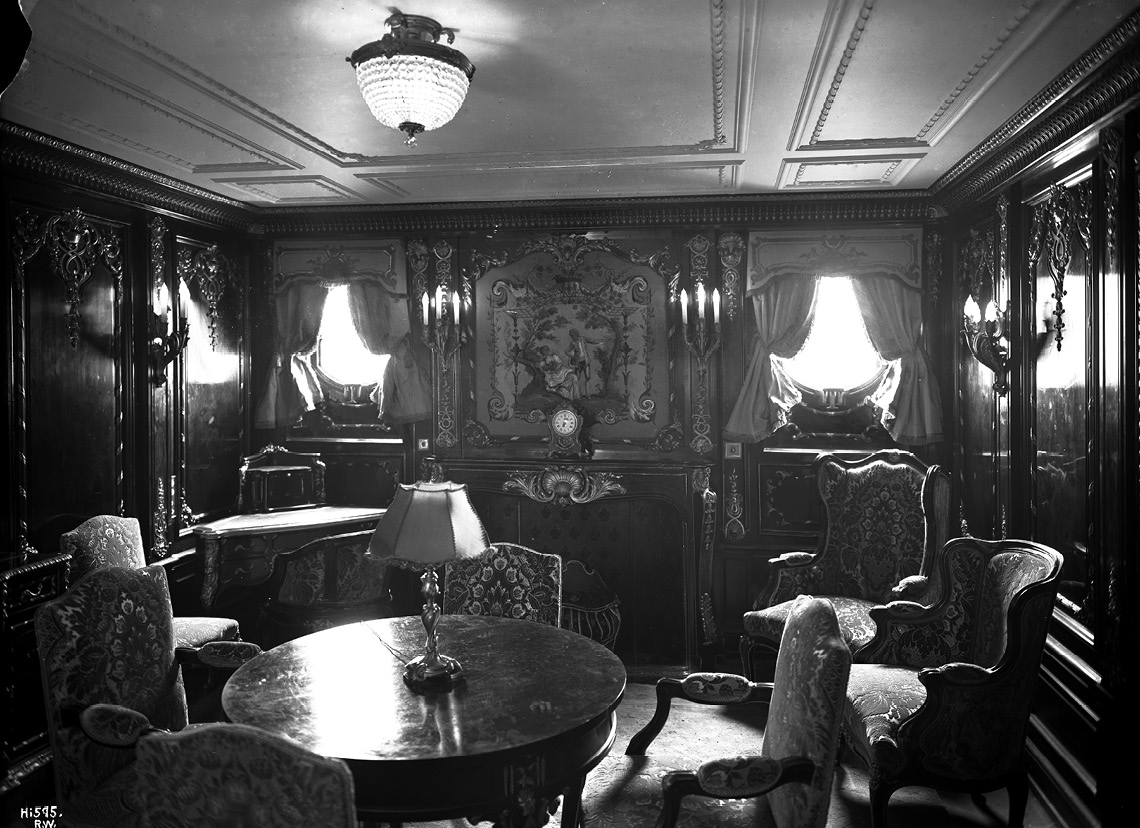

The parlor in the Strauses’ suite on the Titanic was identical to its counterpart on the Olympic. The desk where Ida wrote her letter to Lilian Burbidge can be seen on the far left.

Ten doors up from the Countess’s new stateroom, sixty-three-year-old Ida Straus, traveling with her husband, Isidor, a former Democratic Congressman for New York and co-owner of Macy’s department store, was thrilled with her quarters. The Strauses had taken a parlor suite, which gave them a bedroom, a drawing room, a bathroom, and ample wardrobe space. The layout of their rooms, C-55 and C-57, was almost identical to the same suite on the Olympic, from which several photographs fortunately survive showing in detail the parlor and bedroom occupied by Ida Straus and her husband.I39 The drawing room was decorated in an Edwardian take on the Regency era, with three-armed candelabra mounted throughout on the room’s mahogany walls, flecked with interweaving gold leaf. A tapestry of a pastoral scene, vaguely in the style of Fragonard, was displayed between two curtain-draped portholes and above the fireplace with its electric heater. On a table in the center of the room, a large bouquet of flowers had been waiting for Ida when she arrived, a gift from Lilian Burbidge, wife of Richard Burbidge, managing director of Harrods. The two couples had spent some time together during the Strauses’ recent stay in London, during which the Burbidges had taken them to the theater and supper, favors which Ida planned to repay when the British couple visited New York the following summer.

The Atlantic Ocean had framed Ida and Isidor Straus’s life together. Both were first-generation Americans, having immigrated to the United States as children—in Isidor’s case from the kingdom of Bavaria and in Ida’s from the grand duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt, two decades before both territories were incorporated with varying degrees of unwillingness into a unified Imperial Germany. Transatlantic travel then had been fraught with possible dangers and certain discomfort, but it had already begun its meteoric sequences of improvement when the couple first met in New York in the 1860s, at a time when their families were on opposite sides of the American Civil War and Isidor, who had then lived in Georgia, was preparing to sail back to Europe to work as a blockade-runner for the Confederacy. He had called on old friends of his family in New York, including the young Ida Blun’s parents, before booking passage to England, while maintaining the pretense of being a Northerner under which he had arrived. By the time they met again and fell in love, the Confederacy as a political actuality had been wiped from the face of the earth and the Strauses had emigrated once more, this time trading Georgia for New York. Since then, there had been numerous trips across the Atlantic for the couple, initially because of Isidor’s desire to remain in touch with his German relatives and to visit London, a city he had fallen in love with during his time there in the 1860s.40 Ida preferred Paris, partly thanks to her love of shopping; her husband tolerated rather than enjoyed their stays there.41

Isidor remained fascinated by liners and their technology, so the couple made their way on deck for the send-off, stopping at the end of their corridor to chat with a stewardess, who had once attended to them on the Olympic and thought them “a delightful old couple—old in years and young in character—whom we were always happy to see join us.”42 When they reached the deck, they fell into conversation with their friend Colonel Archibald Gracie IV, who like Isidor came from Confederate stock—his father, General Archibald Gracie III, had been killed by a Union shell at the Siege of Petersburg in 1864.43 Knowing that mail would be taken off the ship at Cherbourg in a few hours’ time, Ida wanted to make sure she sent a prompt thank-you note to Lilian Burbidge for the flowers and, since the Strauses had been spending the winters in Europe away from their New York home every year since 1899, the anchors-away moment no longer held much of a thrill for Ida.44 While Isidor stayed up top with Gracie, Ida, by 1912 plump and elegant with a cloud of dark hair beginning to show streaks of gray, with a prominent flesh-colored mole on the lower left-hand side of her face and a warm smile which many people considered her best feature, made her way back to their suite, sitting at its little escritoire beneath one of the portholes, while her new maid, Ellen Bird, and Isidor’s English valet, John Farthing, began the long process of unpacking.45 Ida was a particularly hands-on housewife, who was almost alone among the wealthy women of Manhattan in never having hired a housekeeper; Isidor was constantly urging her to take on fewer responsibilities.46 It had been a series of nervous complaints and then problems with Ida’s heart, flaring up with regularity over the previous three years, that had turned their annual migration to the French Riviera into something approaching a necessity. When they could not spend too much time away from America, Ida had gone to relax at their beach house in New Jersey and once to California.47 That year, they had left New York in January aboard the Cunard Line’s Caronia, which plied the route from Manhattan to the Mediterranean, and spent most of their holiday at a quiet hotel in Cannes, which Ida in a letter home to her married daughter, Minnie, had described as “a lovely spot for old people.”48 But Ida had made something of a poor swap, since New York had one of the mildest winters that anyone could remember, while the Riviera was pelted by rain for most of February and March.II

From five decks beneath her, the Titanic’s engines roared to life, producing a quiet hum beneath Ida’s feet and in the walls around her. Many of the passengers would remark later that the ship was so well designed that they were barely aware of the vibrations, although they certainly noticed them when they stopped, since the engines muffled much of the noise flowing between the relatively thin walls of the cabins.49 The Strauses’ rooms, like the Countess’s, were on the Titanic’s starboard side, facing away from the pier, but the noise would have given Ida a general idea of what was going on. Far above her, the scream of the ship’s whistles and the cheers of the crowd announced that it was time for the Titanic to make her midday departure, only a few minutes late.50 Then, a silence fell as the engines cut out and the Titanic floated adrift in the River Test, until the reassuring growls of the machinery eventually returned and the journey continued.

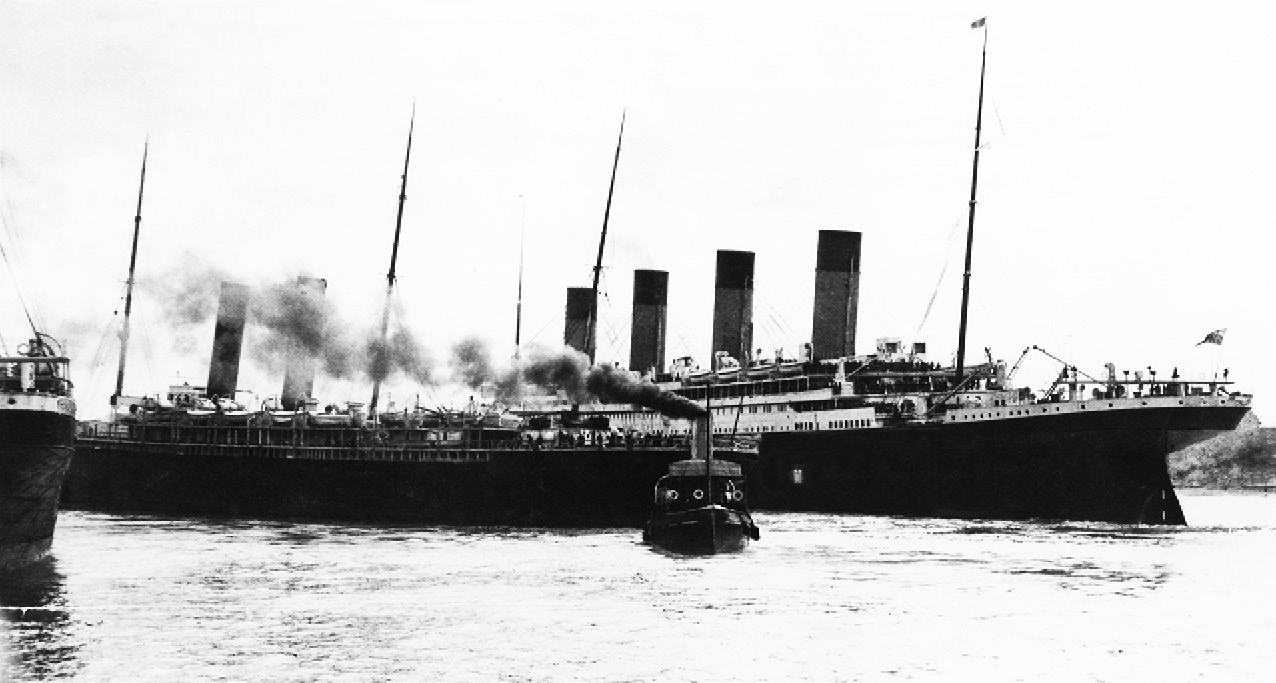

This photograph caught from the pier shows just how close the New York came to colliding with the Titanic.

An explanation for this arrived when her husband returned. Sixty-seven years old, bald, with a well-trimmed white beard and occasional pain in his legs, Isidor told Ida that, as the Titanic set off, the suction from her three enormous propellers had caused the New York to break free from her moorings and drift towards her. A quarter of a century earlier, Isidor had sailed on the New York’s maiden voyage from Liverpool, when she had been considered “the last word in shipbuilding.”51 In a harbor overcrowded by ships laid up by the miners’ strike, the coils of the ropes mooring the New York had snapped with a noise like gunfire, whipping back onto the docks to lacerate a woman in the crowd, who had to be rushed away to receive medical attention. For one horrible moment, it looked as if there would be a repetition of the Olympic’s accident the previous year, with a smaller ship sucked into a voyage-canceling collision.52 The Titanic’s Captain had moved quickly to halt the churning of the propellers, giving those in the guiding tugboats time to maneuver the New York back to safety.53

The Titanic’s schedule had been dented before she even left her home waters, but she was intact. Later, many chose to reinterpret the near miss as an omen, such as the large flock of seagulls that Cissy Maioni noticed following the Titanic overhead as the ship resumed her journey.54 Ida, however, turned back to her letter to Lilian Burbidge, as the waters of the Test became the Solent and then the Channel:

On Board R.M.S. Titanic

Wednesday

Dear Mrs. Burbidge,

You cannot imagine how pleased I was to find your exquisite basket of flowers in our sitting-room on the steamer. The roses and carnations are all so beautiful in color and as fresh as though they had just been cut. Thank you so much for your sweet attention which we both appreciate very much.

But what a ship! So huge and so magnificently appointed. Our rooms are furnished in the best of taste and most luxuriously and they are really rooms not cabins. But size seems to bring its troubles—Mr. Straus, who was on deck when the start was made, said that at one time it stroked painfully near to the repetition of the Olympian’s [sic] experience on her first trip out of the harbor, but the danger was soon averted and we are now well on to our course across the channel to Cherbourg.

Again thanking you and Mr. Burbidge for your lovely attention and good wishes and in the pleasant anticipation of seeing you with us next summer. I am with cordial greetings in which Mr. Straus heartily joins,

Very sincerely yours,

Ida R. Straus55

I. The counterpart of their suite on the Olympic was later offered to the future King Edward VIII when he returned on board from his visit to the United States in 1924. He asked to be moved to another room, because it was “too pretty for me.” The rooms were then assigned to the Prince’s groom-in-waiting, Brigadier General Gerald Trotter. Why the Prince felt this way is unclear, given that his famous future home in the Bois de Boulogne did not exactly reek of the spirit of Sparta.

II. There remains some confusion about the Strauses’ itinerary that spring, with several modern accounts stating that they also visited Jerusalem and Palestine. However, it was Ida’s brother-in-law, Nathan Straus, who made the trip to Jerusalem in 1912, with his wife, Lina. En route, they stopped to spend several days with Ida and Isidor, but there was no time for the latter to join them as they traveled further east. They were still in Cannes when Ida and Isidor’s youngest daughter, Vivian Scheftel, briefly joined them with her husband and children.