CHAPTER 4 A Contest of Sea Giants

To the battle of Transatlantic passenger service, the Titanic adds a new and important factor, of value to the aristocracy and the plutocracy attracted from East to West and West to East. With the Mauretania and the Lusitania of the Cunard, the Olympic and Titanic of the White Star, the Imperator and Kronprinzessin Cecilie of the Hamburg-Amerika, in the fight during the coming season, there will be a scent of battle all the way from New York to the shores of this country—a contest of sea giants in which the Titanic will doubtless take high honours.

The Standard (April 5, 1912)

PASSENGERS WAITING TO BOARD THE Titanic at Cherbourg, the first of two European ports of call after Southampton, were told of the delay that had arisen as a result of the New York incident by Nicholas Martin, manager of the White Star Line’s main French office, who had accompanied the firm’s boat train from Paris earlier that day.1 He broke the news in an uncomfortably pitching tender, the Nomadic, built in Belfast two years earlier and boasting several decorative features like bronze grilles on the doors as aesthetic anticipations to the interiors of her destinations—either the Olympic or the Titanic, both too large to dock in Cherbourg’s harbor. First- and second-class passengers were ferried to the waiting liners on the Nomadic; Third Class and mail were brought out by her partner, the Traffic.2 Embarkation had been tentatively rescheduled by about ninety minutes for about five thirty, at which time, despite the fact that the Titanic had still not actually come into view, the Nomadic’s skipper moved her off from the little quay and out into the breakwater, where it unhappily became clear that the lovely spring weather had obscured a strong breeze and equally lively currents. Many of the Nomadic’s 172 passengers became nauseous, either from the pitch or from the enforced coziness of the crowded boat.3 Several false sightings of the Titanic raised hopes whose disappointment nurtured irritation. Those with better sea legs distracted themselves with a “slight and passing interest in a fishing boat—[then] more waiting.”4

Grouped together in the Nomadic’s stultifying saloon were names that had already earned the Titanic’s crossing a press-created nickname of “the Millionaire’s Special”—Astors on the final stretch of their honeymoon, a Guggenheim ending his winter on the Riviera, a presidential adviser emerging from a recuperative stay in Rome, and a celebrated art historian returning to fractious negotiations about the design of the proposed Washington, DC, memorial to President Lincoln. By a considerable margin, Americans constituted the majority of the Titanic’s first-class ticket holders, and the reason for this lay in the approaching summer Season. The East Coast upper class’s Season in the United States fell at about the same time as that of their British counterparts, but with far greater precision, lasting from Memorial Day, then commemorated on May 30, until Labor Day, on the first Monday in September, at which point wearing white slipped from a proclamation of belonging to an advertisement of bad taste. Well serviced by railways from the Paris terminals, Cherbourg proved a convenient point of embarkation for those who had spent their winters in the South of France or, equally popular with traveling Americans, Italy.

John Thayer, second vice president of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company.

Heavy-jawed, thickly but tidily mustachioed, and eleven days short of his fiftieth birthday, John Borland Thayer Sr., second vice president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, was, like many on the Nomadic that afternoon, a beneficiary of, and participant in, perhaps the greatest sustained economic expansion in recorded history. The assets of the most fantastically beneficed courtier at Versailles in the middle of the eighteenth century would have paled in comparison to the wealth of the American industrialists created in the nineteenth. The first few generations of American millionaires had led the surge that took their country from being the British Empire’s most rebellious child to becoming its competitor and, in the years after 1912, its successor—in 1800, American factories produced just one-sixth the amount churned out in the United Kingdom; by the time the Titanic sailed, they were making 230 percent more, accounting for 32 percent of global industrial production, compared to 14 percent from the admittedly far smaller Britain.5 This growth had been sustained, at least initially, by an appalling humanitarian cost to America’s laborers—“the cost of lives snuffed out, of energies overtaxed and broken, the fearful physical and spiritual cost to the men and women and children upon whom the dead weight and burden of it all has fallen pitilessly,” in the words of Woodrow Wilson, the soon to be Democratic nominee for the US presidency.6 When the heir to the Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, visited the United States in 1893, he had praised the Great Republic’s federalist structure but expressed horror at the treatment of the country’s workers, who, he believed, endured conditions far worse than anything seen in the more technically unequal kingdoms and empires of Europe. It was after his stay in New York that Franz Ferdinand concluded that in America, it seemed to him, “for the working class, freedom means freedom to starve.”7 The Archduke’s depressing conclusions were unknowingly corroborated by one of his uncle’s former subjects, an immigrant to New York called Faustina Wi´sniewska, who wrote home to her parents in the same year to tell them that “here they exploit the people as they did the Jews in Pharaoh’s time,” and by several prominent American industrialists, like bosses at the Carnegie steel conglomerate who issued advice to avoid placing orders with foreign factories, not for any reasons of national loyalty, but because foreigners, particularly the British, were “great sticklers for high wages, small production, and strikes.”8

By the turn of the century, many of the children and grandchildren of the plutocratic pioneers had sought to beautify and perhaps exorcise their legacy with a gilding borrowed from the once rejected hierarchies across the Atlantic. Palatial homes were built in imitation of the Trianon, Grand and Petit, albeit with modern plumbing, wiring, and far better heating. The tribe was demarcated with rules as rigid as Habsburg Spain’s and a similar sense of self-worth. One of the Astors boarding the Titanic was a son of the famous socialite whose ballroom’s capacity of four hundred had set the parameters of what constituted polite New York Society, known thereafter as “the Four Hundred”—“If you go outside that number you strike people who are either not at ease in a ballroom or else make other people not at ease,” explained one member of the sacred band. In that rarefied milieu, Mrs. Astor had been compared by one admirer to Dante’s version of the Virgin Mary in The Divine Comedy, only here the “circulated melody” surrounding the blessed lady was the Manhattan elite rather than the heavenly host, and the sparkle of the twelve celestial stars in the Virgin’s crown had been replaced by so many family diamonds that Mrs. Astor was likened to a chandelier by a guest at one of her annual January balls. There she greeted guests sitting in a thronelike chair before a life-size portrait of herself, with her Fifth Avenue mansion staffed by footmen dressed head to toe in a livery inspired by that worn by the British Royal Family’s servants at Windsor Castle.9 The fashions, sports, and manners taught at Eton, Harrow, and Winchester were imported and applauded, as were countless art treasures which were bought, shipped, and quite probably saved from crumbling European palazzos, manors, castles, and monasteries.

Following the Anglophile trend had come easily for John Thayer. Both he and his wife, Marian, ten years his junior, were scions of old-money families from Philadelphia, America’s first capital, where Society predated the War of Independence. There had been born a class that would later jokingly be dubbed the acronymic WASPs, since they were all white and nearly all Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Thayer’s life had played out along the paths paved by this self-created aristocracy, beginning with prep schools and then an Ivy League education, where he had excelled at lacrosse. His summers had been divided between the family’s main home on the outskirts of Philadelphia and their sprawling mansion-size cottage by the beach. He had pursued his love of cricket at their local club, Marion, in Haverford, which he represented in 1884 on a team sent to compete in England. That trip had apparently solidified Thayer’s belief that it was only in Europe that one could learn the “correct” way of doing things. After he and Marian Morris married in 1893, jaunts across the Atlantic had become a regular part of their annual routine. That year, they had been accompanied by their eldest son, John Thayer III, known as “Jack” in the family.10 Seventeen years old, tall, blond, athletic, and an excellent swimmer, Jack was sitting next to his parents on the Nomadic, returning to his three younger siblings and home, where as a student of the nearby Haverford School he would begin the application process for Princeton, after which he would be sent back to Europe for a few years of apprenticeship in private banking. In his words, “It could be planned. It was a certainty.”11

As the Nomadic and the Traffic made their way slowly towards the arriving Titanic, Tommy Andrews watched from the deck, anxiously inspecting their progress. A year earlier, the White Star Line had retired their antiquated tenders in favor of new constructions from Harland and Wolff to service the Olympic’s maiden stop at Cherbourg.12 Relieved that the ferries still seemed to be working as expected, Andrews went back to his cabin to pen a brief letter to his wife, containing the observation, “We reached here in nice time and took on board quite a number of passengers. The two little tenders looked well, you will remember we built them a year ago. We expect to arrive at Queenstown about 10:30 a.m. to-morrow. The weather is fine and everything shaping for a good voyage.”13

The Titanic arrived just at the dying of the afternoon light with the sun setting behind her, and by the time of the last embarkation the liner’s decks, windows, and portholes were illuminated against the night. As they approached, Edith Rosenbaum, an American fashion journalist returning from the Paris spring shows, observed, “In the dusk, her decks were 11 tiers of glittering electric lights. She was less a ship than a floating city, pennants streaming from her halyards like carnival in Nice.” One of the Astors opined, “She’s unsinkable. A modern shipbuilding miracle.”14 The Nomadic’s passengers gazed up at a ship weighing just over 46,000 tons, nearly 883 feet long and 92 feet wide, rising roughly to the height of an eleven-story building beneath four funnels, their top quarters painted black and the rest in the buff yellow that constituted the White Star Line’s livery.15 The last of those funnels was a dummy, used for ventilation, obviating the need to build as many on-deck ventilation shafts as were required on other ships. This decision by Andrews and his team had helped create in the Titanic and her sisters three extraordinarily elegant ships. They had more in common with the smooth lines of the private yachts of European royalty than with their often bulky commercial rivals. Particularly when seen in profile, the Olympic-class liners were blessed with a clean and appealing gracefulness, a fact frequently praised in shipbuilding journals and contemporary travel guides.16 The earliest designs for the Titanic had apparently suggested only three funnels, but the White Star Line concluded that four were indelibly associated with great ships in the traveling public’s mind, thanks largely to a class of ships that had emerged from the Thayers’ last stop before Cherbourg.17

Prior to boarding the Titanic, John Thayer and his wife had spent some time visiting Berlin as guests of both the US Consul General, Alexander Montgomery Thackara, and the new American Ambassador, John Leishman, who had previously served as the US representative to Switzerland, the Ottoman Empire, and Italy. Although it had existed for hundreds of years as Prussia’s capital, as Germany’s Berlin remained new, high on hustle and low in majesty, with most traces of the provincial capital vanishing in pursuit of modernity. Berlin, like Belfast, seemed ever expanding; Mark Twain had once quipped, “Next to it, Chicago would appear venerable.”18 Nonetheless, it was European and, like Thayer, Leishman was persuaded of the European way of doing things, at least when it came to manners if not to business. Unhappily, by the time the Thayers arrived as guests of the embassy the Ambassador had run aground on some of the Old World’s less appealing attributes. His eldest daughter had already married a French count when her younger sister, Nancy, received a proposal from Prince von Croÿ, who was in the happy and increasingly unusual position of possessing both a fortune and a pedigree like Midas’s. Nancy, as an American and a commoner, was counted as defective on two fronts by the Prince’s formidable aunt, the Archduchess Isabella of Austria, and in her crusade to prevent the nuptials, the Archduchess enlisted the help of the German Kaiser, who was traditionally required to give his blessing to the marriage of a subject as high-ranking as von Croÿ.19 This the Kaiser declined to give, causing a rupture with the American Ambassador, who was understandably mortified by the insult to his daughter. As the newspapers buzzed with the scandal, relations between the Kaiser and the Ambassador deteriorated to the extent that, after Nancy and the Prince married without imperial permission in October 1913, Leishman felt he had no choice but to resign.20

For the Thayers, their trip to Germany had also offered an opportunity to see one of the world’s most prosperous states. With plenty of fertile agricultural land, huge natural reserves of coal and iron ore, and population growth sustained by an increasingly excellent health-care system, Imperial Germany also stood at the forefront of new industries like electrical engineering, as well as steel and chemical production. Germany’s public education system was superior to those in Britain, France, and America, while conditions for its working classes, particularly after the development of its sophisticated welfare state, meant that a German factory worker’s average life expectancy was about five years longer than the British equivalent’s and nearly two decades longer than a Russian’s. This spate of progress was rendered all the more remarkable by the fact that Germany had existed as a political entity for only forty-one years by the time the Titanic sailed on her maiden voyage.

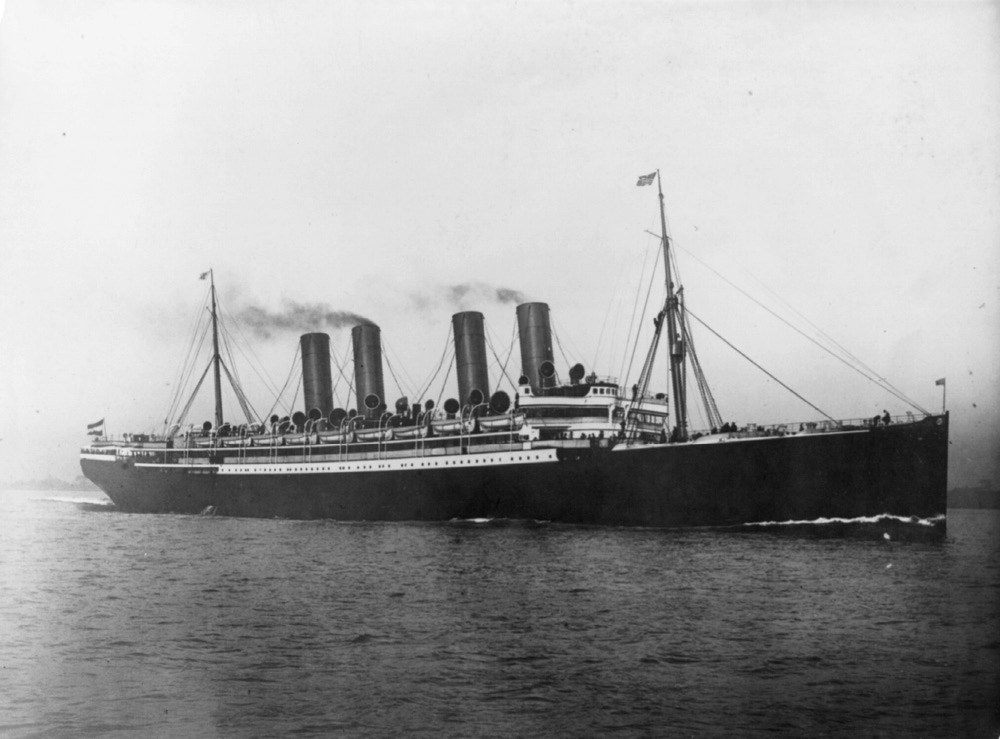

The recession of Habsburg influence in Germany after the Napoleonic Wars had allowed the northern kingdom of Prussia, ruled by the House of Hohenzollern, to assume primacy and eventually, in 1871, to unite the many kingdoms, grand duchies, principalities, and states into the Second Reich, with the King of Prussia installed as hereditary German Emperor.21 The other pre-unification German rulers kept their wealth, titles, prestige, and varying degrees of regional influence, but it was the culture of Prussia—confident, militarist, and expansionist—that dominated the new empire. This caused particular concern in London, Paris, and eventually St. Petersburg. Despite being the son of a British princess, upon his succession to the German throne in 1888 Kaiser Wilhelm II did little to allay British fears and much to exacerbate them. In some ways, the Titanic’s genesis lay with the Kaiser’s dichotomy when it came to his mother’s homeland—devout emulation grinding against suspicious competition. Wilhelm II’s passionate interest in the mercantile marine had, in fact, begun thanks to a White Star liner, the Teutonic, when, during the Kaiser’s 1889 visit to the United Kingdom, she had been picked to underscore Britain’s commercial and military dominance of the oceans. Wilhelm had been invited to a naval review at Spithead and then, in the company of his uncle, the future Edward VII, offered a tour of the Teutonic. If the intention had been to intimidate the German Emperor, or gloat, it backfired spectacularly. Instead, as he viewed the Teutonic, the Kaiser was apparently heard to remark, “We must have some of these.”22 In 1897, imperial encouragement, the sustained economic miracle of the Second Reich, and a booming eastern European migrant trade for which the German ports proved more convenient points of embarkation to America than their rivals in Italy, France, and England, wove together to create the Kaiser Wilhelm der Große, the first transatlantic liner with the soon to be iconic four funnels. Christened after the Kaiser’s late grandfather, the ship was a sensation—hugely popular with all classes of travelers, particularly European emigrants and affluent Americans—and lavishly decorated with the fantastically overwrought designs of Johann Poppe. A contemporary joke described the aesthetic as “two of everything but the kitchen range, and then gilded.”23 Six months after her maiden voyage, she took the Blue Riband, the award for the fastest commercial crossing of the North Atlantic.24 Her success was sufficient to inspire her owners, the Norddeutscher Lloyd, to commission three running mates over the next decade, all likewise named for, and launched in the presence of, members of the German Imperial Family.25 A testament to how important these ships were to the German Empire’s sense of self was delivered via Our Future Lies upon the Water, a large allegorical mural painted for the first-class Smoking Room of the Kronprinz Wilhelm; it depicted conquering sea gods in aquatic chariots, holding aloft tridents and a banner that looked suspiciously like the German flag.26 There seems to be no truth in the story that the last of the quadruplets, the Kronprinzessin Cecilie, bearing the name of the Kaiser’s daughter-in-law, Cecilia of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, which should logically have been the largest of the four, had her gross tonnage registered as one ton less than that of the third ship in the series, the Kaiser Wilhelm II, in deference to the Kaiser’s enormous yet fragile ego. In fact, the Kronprinzessin Cecilie was publicly listed as the heaviest of the four sister ships, with 19,400 tons against the Kaiser Wilhelm II’s marginally smaller 19,361.27

The first of the greyhounds: the Kaiser Wilhelm der Große.

Nicknamed “the German greyhounds” and “the Hohenzollerns of Hoboken” after Norddeutscher Lloyd’s piers on the Hudson, the Kaiser class transformed the transatlantic trade by proving the idea of the commercially viable super-ship.28 Norddeutscher Lloyd’s home-grown rivals, the Hamburg-Amerika Line, retaliated with their own four-stacker speed queen, the Deutschland. Reflecting on the race thirty years later, the maritime historian Gerald Aylmer wrote, “By 1903 Germany possessed the four fastest and best appointed merchant ships afloat, with another on order. This state of affairs was not palatable, to put it mildly, to Britain, a country which had always prided itself on its steamship construction and speed.”29 Aylmer was right; the success of the Kaiser class inflamed within the British a fear born of the belief that their place in the world was tied inextricably to mastery of the sea-lanes, which had as much to do with their passenger and cargo ships as it did with their dreadnoughts and destroyers. During the Second Boer War, between 1899 and 1902, the White Star Line had donated several of its ships to temporary military service with the Royal Navy, which, combined with unease at the success of the German greyhounds, helps explain the British reaction when White Star was purchased by J. P. Morgan’s conglomerate in 1903.30

A few years earlier, the writer and apostle of British imperialism J. A. Froude had sounded like the voice of Cassandra when he warned his compatriots, “Take away her merchant fleets, take away the navy that guards them; her empire will come to an end; her colonies will fall off like leaves from a withered tree; and Britain will become once more an insignificant island in the North Sea.”31 In 1903, despite assurances that it was only White Star shares and not her ships that were passing into American control, the sale was sufficiently worrying to inspire speeches in Parliament, a mood turned brilliantly to their advantage by White Star’s main British competitors, the Cunard Line, who intimated that they too were considering joining Morgan’s International Mercantile Marine. Suppressing the news that they had in fact already passed on a too low offer from Morgan, Cunard presented themselves as the firm who could gladly recapture Britain’s seagoing pride if only they had sufficient funds to prevent the ugly necessity of selling out to an American.32 The government and the press took the bait. To help with their plan to outshine the Kaiser class, Parliament voted Cunard a £2.5 million loan to be repaid over the next twenty years at 2.75 percent interest, materially and obviously below the base rate of 3–4 percent, coupled with an annual £150,000 operating subsidy.33 In the autumn of 1907, Cunard delivered on the investment with the creation of the Scottish-built Lusitania and then her English-constructed sister, the Mauretania.34 The latter was marginally larger and ultimately proved slightly faster as well, but with both sisters weighing in at about 32,000 tons, each was almost twice as heavy as the largest of the German greyhounds.35 For the next three years, the Lucy and the Maury, as they were nicknamed by their legions of loyal customers and ship enthusiasts, cheerfully passed the Blue Riband between them until, in 1910, the Mauretania decisively took the prize with a crossing time of four days, ten hours, and forty-one minutes, a record she would hold for the next nineteen years.36

Outflanked by the Germans and then by Cunard, Morgan and the White Star Line felt called upon to respond in similarly bombastic fashion, with three floating palaces to Cunard’s two, each of which was to be half as heavy again as the Mauretania. Thus was the Olympic class born. In retaliation, Cunard had ordered a third behemoth, the Aquitania, due to sail from Liverpool to New York for the first time in 1914. Piqued and hitherto overlooked, the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique was preparing to unveil their “château of the Atlantic,” the France, on her maiden voyage a few weeks after the Titanic’s, around the same time as the Kaiser planned to travel north to Bremerhaven to launch the Imperator, which, a year later, would pluck the sobriquet of “world’s largest ship” from the Titanic by a margin of six thousand tons, a development that had forced a change of name for the Titanic’s youngest sister, even as she was being built in Belfast. Just as the names of Cunard ships, prior to the 1930s, ended with -ia thanks to the company’s policy of making use of provinces of the Roman Empire, White Star vessels were typically branded with an adjective transformed into a noun, ending with -ic. The Titanic and her two sisters were named after great species in Greek myth, respectively the gods of Olympus, the titans, and the giants. However, the original name of Gigantic for the third sister never made it past a few provisional poster ideas and excitable press articles. In May 1912, the White Star Line filed the necessary papers to reserve the off-theme but patriotic name Britannic for their forthcoming flagship.

For decades, this shift has popularly been attributed to White Star’s desire to distance the third sister from the tragedy of the second by abandoning a too similar name. This is a logical explanation for how the Gigantic became the Britannic, especially in light of White Star officially filing for the new name a few weeks after the Titanic sank, but it is also incorrect. The alternative name of Gigantic seems to have been genuinely considered by the White Star Line only at the earliest stages in the vessel’s development, and some of their contractors continued to use it even after it had been abandoned—the order books for the English firm that made the liner’s anchors referenced her as Gigantic as late as February 20, 1912—as did several Harland and Wolff employees, who remembered the original name in interviews given in the 1950s. Rumors that the ship was to be christened Gigantic were current and firmly denied by the White Star’s managing director, both in his testimony to the American inquiry into the loss of the Titanic and subsequently in a letter to a British newspaper.37 Those printed denials may have been the company’s response to letters they had received from concerned members of the public, begging them not to tempt fate by giving the new ship a name so similar to the Titanic’s, although at least one of the latter’s survivors was sufficiently hardy to dismiss that as superstitious nonsense, “almost as if we were back in the Middle Ages.”38 More prosaically, it was almost certainly the Imperator that prompted the rechristening. Since, by 1915, the Britannic would “only” be the third largest ship afloat, behind the Imperator and her 1914-projected running mate, the Vaterland, to call her Gigantic under those circumstances seemed foolhardy.39

The Titanic’s looming black-painted hull, summoned into being by capitalist competition and the diplomatic thrombosis of prewar Europe, greeted the Thayers as the Nomadic at last docked alongside the Titanic. The tender’s gangplank could not safely reach the B-Deck embarkation doors used at Southampton and so Tommy Andrews had designed another, two decks lower, reaching a vestibule which opened onto the first-class Reception Room, where stewards waited to guide first-class passengers to their cabins and second-class travelers aft to their section of the ship. Standing in front of the Thayers as they boarded was J. Bruce Ismay, son of the White Star Line’s late founder and managing director since its merger with the IMM. If the Titanic’s legend has a two-dimensional caricature, it is Ismay, cast as both vulpine villain and a serial weakling in the hysterical aftermath of the sinking. So complete was Ismay’s historiographical evisceration that when a consultant first saw the script for what became a multi-Oscar-winning cinematic romance set on the Titanic and queried the characterization of Ismay as a megalomaniacal moron, butt of penis-envy jokes he cannot understand, and shameless manipulator of the Captain in the dangerous quest for more speed, he was told there was no point in changing it because “the public expects” a heinous Ismay.40 That is not to say that Ismay was incapable of moments of mind-boggling stupidity, but he was also astute, devoted to his company, and, like Tommy Andrews, obsessed with detail.41 A complex man whose inherent shyness produced acts of great kindness and flinch-inducing obtuseness, Ismay’s thoughtfulness had won out on April 10 as he bore down on the Thayers’ traveling companions and lifelong friends, Arthur and Emily Ryerson, who were returning home to America unexpectedly after hearing that their son, Arthur Junior, had been killed in a car accident during his sophomore spring at Yale. He had gone home for the Easter weekend to Bryn Mawr in Pennsylvania, where he had died, along with his classmate John Hoffman, two days before the Titanic sailed.42 Ismay took over from the Thayers as temporary chaperone of the grief-stricken by informing the Ryersons, who were traveling with their three younger children, a maid, and a governess, that he had arranged for them to be given an extra stateroom adjoining those they had already booked, along with a personal steward to look after them during the voyage.43 A broken Emily Ryerson intended to spend the trip in her cabin with her family, avoiding everyone else on board except the Thayers.

Less solemnly, a middle-aged New York widow, Ella White, was carried past the boarding passengers. She had fallen and sprained her ankle as the gangplank swayed in the winds.44 A few stewards had been summoned to help Mrs. White’s chauffeur lift her to her C-Deck stateroom, the same deck where the Thayers were also settling into their accommodation on the opposite corridor to the Strauses and the Countess of Rothes. The latter escorted her parents down to the Reception Room to see them off onto the Nomadic. Noëlle, Thomas, and Clementina descended the staircase into the Reception Room. At the bottom of the stairwell, they turned left at a wall mounted with a reproduction of the Chasse de Guise tapestry, depicting a hunting party, the original of which had been owned by the French aristocratic family unfairly accused of poisoning the 4th Earl of Rothes in the sixteenth century.45 From two sets of double doors leading off the Reception Room into the Dining Saloon, the Countess and her parents heard hundreds of passengers tucking into their second meal of the voyage. They walked over dark Axminster carpets, past settees, armchairs, white cane chairs with green side pillows, potted palms, and a Steinway piano, one of six on board, into the small vestibule that opened onto the gangplank and the night air.46 Thomas and Clementina said their farewells, but at the last minute the normally reserved Clementina turned on impulse and dashed back to give her daughter a final embrace.47 When the Dyer-Edwardeses joined the Titanic’s thirteen other cross-Channel ticket holders in the tender, the gangplank was disengaged and the boarding doors were closed. After they had been locked, crew members pulled wrought-iron gates back into place to shield the utilitarian steel from the passengers’ view.

The usual expectations governing dinner, including the formal dress code, were typically eschewed on the first night out.48 Wearing the dress in which she had boarded, Noëlle left the vestibule for the Saloon, which has since become one of the Titanic’s most recognizable rooms thanks to its frequent depiction in silver-screen dramatizations of the voyage.49 Meals in the Saloon were run on the same lines as they might be in a country house on shore, with limited options, generous portions, set times for each course every evening except the first, and placement decided by the host—in this case, the ship’s Purser, who assigned passengers to one of the 115 tables which variably sat two, three, four, five, six, eight, ten, or twelve. His decisions with this social roulette could introduce a passenger to delightful weeklong shipboard acquaintances or purgatorial companionship in a multicourse dinner that moved with the sprightliness of a state funeral. You could, of course, ask the Purser’s Office to move you to another table if you found the company particularly stultifying but, as a passenger on the Queen Mary noted later, “the cost of [which] would be the contempt of those still seated at the table you had spurned, and the frozen stares with which they’d greet you on deck for the rest of the trip.”50

Where to put a countess and her companion would have been one of Purser McElroy’s main priorities, and it seems, from a letter sent by one of their stewards, that they won the lottery in their three gastronomic companions. A steward was assigned to every three diners and it was considered proper for those in his care to leave a gratuity at the end of the voyage, the amount of which very often outpaced his wages. The Countess’s steward, Ewart Burr, described her group as being “very nice to run.” He was particularly pleased to have an aristocrat at his table and he made a point of mentioning it in the note he penned to his wife that evening, writing, “I know, darling, you will be glad to know this. I have got a five table, one being the Countess of Rothes, [who is] nice and young.” Burr predicted that they would be generous at journey’s end or, as he put it, “I shall have a good show.”51

The decor in the Dining Saloon was loosely inspired by Elizabeth I’s childhood home at Hatfield Palace and the dukes of Rutland’s house at Haddon Hall. Despite both those buildings being Elizabethan and the Tudor roses in scrollwork on the Saloon’s roof, trade journals described the Titanic’s Saloon as reflective of “early Jacobean times.”52 The green-leather chairs with their oak frames were heavy enough for White Star to do away with the bolted-to-the-floor chairs used on the Kaiser class and the Cunard sisters. This was the only significant innovation in a room that several industry experts dismissed as conventional almost to the point of staid. One admittedly biased observer was Leonard Peskett, designer of the Lusitania and the Mauretania, whose disapproval was laced with a vigorous dose of delight when he saw the near-identical Dining Saloon during his tour of the Olympic in 1911. The Titanic’s Dining Saloon may have been the largest room afloat but it was not, by any stretch of the imagination, the finest, at least not in Peskett’s view or that of many of his colleagues, especially when compared to the two-storied domed Rococo equivalent on the Lusitania.I There was also a problem of overheating caused by the Saloon’s 404 light bulbs, although the chill outside meant that this was unlikely to be a problem on April 10.53

Stewards served the first course on the fine bone-china plates, edged with twenty-two-karat gold and bearing the White Star logo at the center, setting them down amid the small forest of silver-plated cutlery, while water was poured and wine decanted into crystal glassware.54 At 8:10 p.m., some diners began to debate when they would leave Cherbourg; their steward leaned in to inform them politely, “We have been outside the breakwater for more than ten minutes, Sir.”55

I. Peskett’s assertion that the first-class cabins were similarly inferior to the Cunarders’ did not, however, meet with general agreement.