CHAPTER 5 A Safe Harbor for Ships

And doesn’t old Cobh look charming there

Watching the wild waves’ motion,

Leaning her back up against the hills,

And the tip of her toes in the ocean.

John Locke, “Morning on the Irish Coast” (1877)

TO REDUCE THE DELAY CAUSED by the London boat trains and then by the New York, the Titanic’s speed was increased as she made her nighttime crossing of the Celtic Sea from France to Ireland.1 Twenty of her twenty-nine boilers were eventually operational that evening, during which the Captain stayed on the Bridge, rather than make an appearance at his table in the Dining Saloon.2 He did not, apparently, miss much. Even the smoothest of travel days are liable to produce their own special brand of fatigue and many passengers retired early, abandoning the Titanic’s main after-dinner haunts like the Reception and the Lounge, three decks above, long before their respective closing times of 11 and 11:30 p.m.3 One passenger recalled later that their day had been spent “unpacking, making the cabin homelike, getting the lay of the public rooms, trying to determine fore and aft, port and starboard [and] getting the feel of the ship.… Many passengers are so exhausted with farewell parties and preparations for the voyage.”4

At bedtime, those who wanted a restored shine on their shoes left them to be collected from the stateroom corridors, a service that was not required by Ida Straus’s husband as he was traveling with his own valet, Farthing, a man with several years’ service to the Strauses.5 Such familiarity was not yet possible for Ida with her maid, Ellen Bird, who had celebrated her thirty-first birthday two days earlier while packing for a new chapter of her life, in America, after Ida’s maid Marie had quit to marry a barber she had met during the Strauses’ winter holiday on the French Riviera. The weeks during which Marie served out her notice had not apparently been pleasant for anyone involved, and the normally magnanimous Isidor was offended on his wife’s behalf since, as Ida told a relative, Marie had begun “behaving very badly over here. When Papa sours on a girl you know there is good cause, and he is disgusted with her.”6 She had intended to replace Marie with another French lady’s maid, but none could be found by the time the couple left for Britain, where, after another was retained and quit upon changing her mind about moving to America, Ida had hired Ellen on the recommendation of the housekeeper at Claridge’s, their hotel during their London stay. Like the Countess of Rothes’s maid, Cissy Maioni, Ellen came from a family with a history in domestic service and she had been a maid in various households since her early twenties. Although Ida remained worried, as she had been with Marie, about “whether I can count on her,” so far she was pleased with Ellen, whom she described in a letter home as a “nice English girl.”7 Ellen helped prepare Ida for bed, then left for her own cabin, which was in First Class and on the same corridor as the Strauses’.8

The Strauses’ bedroom, located between their parlor and their private bathrooms, was decorated in the style of the First Napoleonic Empire, to which any curve left ungilded was regarded as a curve wasted. They slept in two single beds on opposite sides of the room, separated by the door to the parlor and a marble washstand; there was a dressing table on the other side of the room, along the wall that led to their wardrobe and bathrooms. At sea, as on land, many upper-class couples had separate bedrooms, and so to put them in a double bed when they were traveling was considered infra dig. The Strauses’ decision to share a cabin, if not a bed, thus emphasizes their closeness rather than the opposite. They had shared a room on their previous crossing on the seven-year-old Caronia, which still had bunk beds in some of its best first-class accommodations. Isidor had taken the top berth, and one morning after he had risen, its corner fell, missing Ida’s head by inches. The ship’s purser attributed its collapse to “some peculiar bend or twist of the ship,” although the fact that bunks existed at all on the Caronia showed how far ocean liners’ accommodations had evolved in a relatively short period.9

Their mattresses on the Titanic were firm, on the instructions of J. Bruce Ismay, who had ordered a change throughout First Class after sailing on the maiden voyage of the Olympic, when he had observed, “The only trouble of any consequence on board the ship arose from the springs of the bed being too ‘springy’; this, in conjunction with the spring mattresses, accentuated the pulsation in the ship to such an extent as to seriously interfere with passengers sleeping.”10 While all first-class cabins were located amidships, where the ship was most stable, this was also directly above, albeit far above, most of her elephantine engines, hence Ismay’s insistence on a new type of bedding to cushion any vibrations when the Titanic ran at high speed, as she incrementally began to do after Cherbourg. That evening, the extinguishing of the lamps installed over most of the Titanic’s first-class beds left a nocturnal gloom gently pierced by the glow from the electric heaters provided in every stateroom. The cold in London and the breeze in Cherbourg had followed the Titanic and combined to strengthen.11 In cabins with portholes or windows, even if closed and latched, the chill was felt to some degree and so the heaters hummed in successful combat.12 Fortunately, even as the wind whistled around their temporary home, few of the Titanic’s inhabitants experienced seasickness—she remained on an even keel.IAs one of them put it a few days later, they slept contentedly thanks to “the lordly contempt of the Titanic for anything less than a hurricane.”13

This beacon of lordly contempt was sailing between Land’s End in Cornwall and the Scilly Isles when the sun rose through broken clouds; around the same time, nearly fifty of the ship’s clocks swung in silent unison from about 5:40 to 5:15 a.m.14 As the ship sailed westward, two master clocks in her Chart Room, both displaying time to the second, were adjusted for the crossing of the time zones. Clocks throughout the crew’s quarters and the passengers’ public rooms were linked to these master clocks and adjusted automatically with them. Known as the Magneta system, it did away with the need for crew members to move through the ship manually adjusting individual timepieces.15 Usually the reclaiming of an hour was calculated and implemented for about midnight during the voyage, but in 1912 Ireland operated under Dublin Mean Time, twenty-five minutes behind Greenwich, and the Titanic did not clear English waters until sunrise or shortly after.II As the ship awoke, a small battalion of stewards and stewardesses brought morning tea to the staterooms or breakfast trays for those, like Ida Straus, who had the option of taking the first meal of the day in their private parlors.16 For the rest, the Dining Saloon revived for a two-hour window, beginning at eight o’clock.17

Shortly after breakfast, southeastern Ireland came into view with “the brilliant morning sun showing up the green hillsides and picking out groups of dwellings dotted here and there above the rugged grey cliffs that fringed the coast,”18 according to one passenger’s memoirs. The port they were heading for had first been referred to as “the Cove of Cork,” its nearest city, in the middle of the eighteenth century, which had inspired the town’s subsequent name of Cóbh, an Irish rendering of the English “cove” and pronounced in the same way.19 Following a visit by the young Queen Victoria in 1849, Cóbh had been rechristened Queenstown. However, opponents of the Union with Britain continued to refer to the town by its pre-Victorian name, which was legally restored following Irish independence in the 1920s. Queenstown’s motto, Statio Fidissima Classi (“A Safe Harbor for Ships”), reflected its long history as a busy port, particularly as it became the main boarding point for the millions who emigrated from Ireland in the nineteenth century. By 1912, the Irish diaspora to America had slowed to a steady trickle compared to the anguished flood of previous decades, and the Titanic’s call at Queenstown had more to do with fulfilling the obligations of White Star’s mail contract, through which the ship gained her prestigious prefix of RMS, or Royal Mail Steamer.20

Ports like Liverpool, New York, and Southampton had frequently been dredged to accommodate the recent leaps in liner size, but Queenstown, like Cherbourg, still relied on tenders. The Ireland and the America beetled out into waters turned a murky brown as the seabed sand was churned to the surface by the Titanic’s slowing propellers.21 Sacks of mail, luggage, and 191 new passengers were moved from tenders to the ship, while those taking the air on the Titanic’s Boat or Promenade decks joked about the seemingly minuscule size of the ferries, “tossing up and down like corks” in the swell.22 Many admired the view of Queenstown, particularly the turrets, buttresses, and three-hundred-foot spire of its Catholic cathedral, St. Colman’s, a generation-long endeavor then seven years from completion.23 This idyllic vista, particularly the green hills hugging Queenstown and running to the shore, justified Ireland’s nickname of the Emerald Isle, a phrase allegedly first committed to paper by one of Tommy Andrews’s maternal ancestors, the republican writer William Drennan, who had, to the embarrassment of his Edwardian descendants, sided with the ill-fated 1798 rebellion against the Crown and launched the famous moniker in his poem, “When Erin First Rose.”24

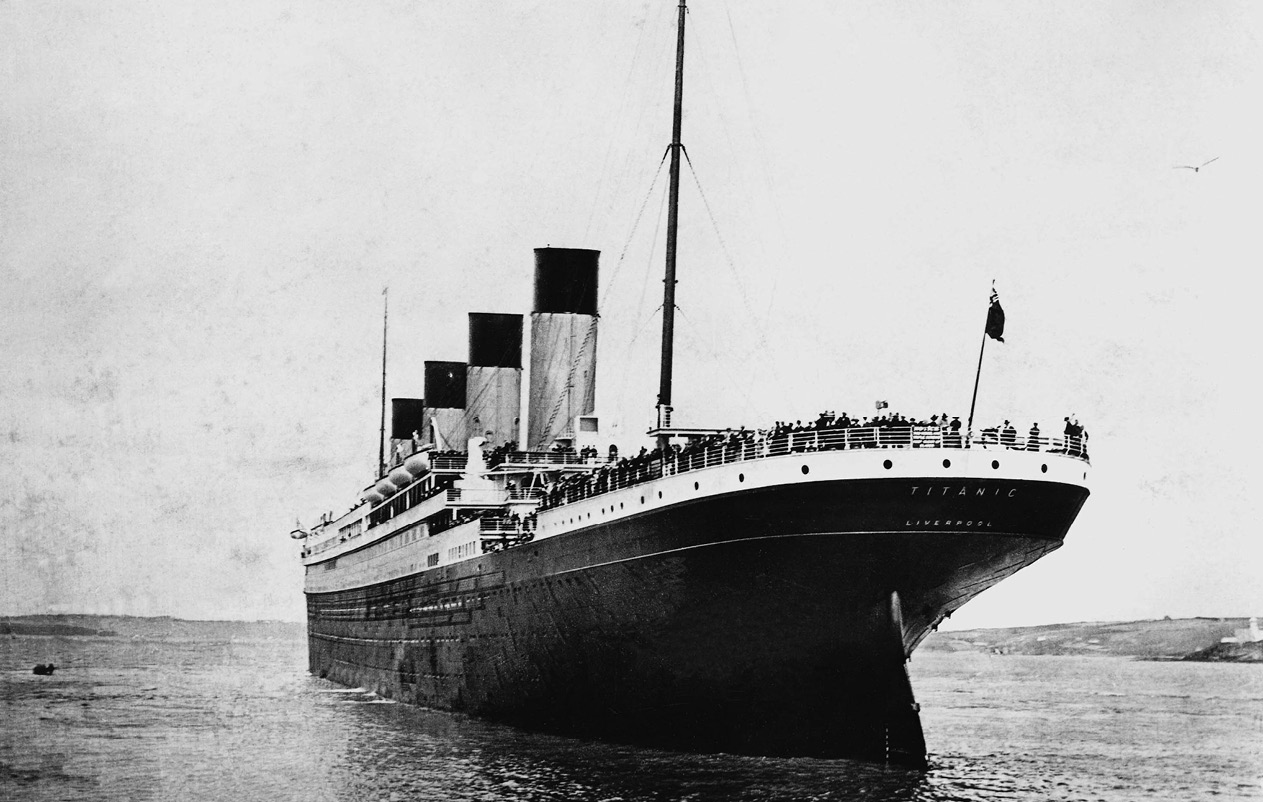

At anchor off Queenstown: many of the passengers visible on the stern were Irish immigrants who had boarded the Titanic in Third Class that morning.

The stop at Queenstown vacated cabin A-37, directly opposite Andrews’s A-36 and occupied by a devout Irish Catholic, thirty-two-year-old Francis Browne, a charming amateur photographer who had gone to boarding school with James Joyce and was later immortalized as “Mr. Browne the Jesuit” in Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake.25 Browne evidently had not lost his ability to make an impression, since at dinner the previous evening two of his companions in the Saloon, a wealthy couple from New York, had been so captivated by his eloquence that they offered to pay his fare if he wished to remain on the ship and at their table until America. Browne, who was reading Theology in Dublin with the aim of pursuing a vocation as a priest, had to ask his superior for the necessary permission to miss his studies for a few weeks. He received a sharply worded reply in telegram form: “Get off that ship.”26 Had the Jesuit professor reached the opposite decision, Andrews might have grown accustomed to seeing Browne’s face throughout the voyage. As it was, the trainee priest was up as early as the ship’s designer to snap away on his camera, mostly in the better lighting provided on the Boat Deck.27

Andrews’s morning produced less picturesque sights, particularly through his inspection of the watertight doors between the ship’s boiler rooms.28 The doors had already been repeatedly tested in Belfast, but a subsequent trial at sea was considered sensible. Almost in unison, the heavy mechanized doors slid into place, sealing the Titanic’s sixteen watertight compartments off from one another, as they would if the hull was ever breached. Joined by the ship’s Chief Officer, Henry Wilde, Andrews then watched to see if the crew could open and close the watertight doors manually with a large specially purposed wrench, in the event of the failure of the doors’ electric controls operated from the Bridge. This too was successfully executed, removing another item from Andrews and Wilde’s to-do list.29 The latter’s posting to the Titanic had been very much last-minute and it was attributed to his service in the same role on the Olympic, where he had been liked and trusted by Captain Smith, who had also been transferred to the Titanic. It may have been Smith’s friendship that prompted Wilde’s appointment only seven days before the Titanic sailed from Southampton, bumping William Murdoch down to first officer and Charles Lightoller to second. There were six officer posts on the Titanic, but since the third officer’s task functioned largely as an apprenticeship to serving as second officer, this meant the previous second officer, David Blair, had become surplus to requirements upon Wilde’s arrival. Wilde, who preferred the Olympic and said he had a “queer feeling” about the Titanic, was no more happy at being summoned than Blair was at leaving “a magnificent ship. I feel very disappointed I am not to make the first voyage.”30 This reshuffling of command had an important, if subsequently exaggerated, impact in the Crow’s Nest, the vantage point on the forward mast. As theirs had not yet arrived, Blair had offered to lend the lookouts his binoculars, which he innocently took with him when he left. When this was brought to Wilde’s attention, he hunted around the ship but there did not seem to be any permanent spare pair to loan to the Crow’s Nest for the duration of the voyage. Some of the lookouts refused to let the matter drop and approached Second Officer Lightoller, around the time the ship reached Queenstown. Lightoller agreed that binoculars would be helpful and went searching for an extra set, though with the same lack of success as Wilde. Other crew members, however, thought the lookouts were creating a fuss over nothing, that one’s eyes ought to be sharp enough to do without binoculars or that they would be a hindrance rather than an aid, since they might seduce a lookout into a sense of complacency or encourage undue focus on a faraway point at the expense of more immediate dangers.

The notoriety of the Titanic’s failure to provide binoculars entered the popular mythology of the tragedy as another potent example of incompetence-laced hubris. The origins of that claim lay with one of the surviving lookouts, Frederick Fleet, who insisted at both subsequent inquiries into the disaster that if he had been provided with binoculars it would have given him more time to warn the Bridge, perhaps “enough to get out of the way.”31 However, modern tests conducted in similar conditions seem to corroborate the views of contemporary seamen who countered Fleet’s testimony by stating that on dark and cold nights on open water binoculars are ineffective to the point of uselessness in spotting objects, particularly ones that are already dark, like a growler iceberg.32

While the Titanic’s anchors remained dropped at Queenstown, journalists from local newspapers and enthusiastic members of the Royal Cork Yacht Club skimmed out in crafts to photograph and admire the liner before, at one thirty, her anchors were raised, the seabed sand was disturbed again as the triple-screw propellers spun back into motion, and she turned slowly to point her prow to the Atlantic. By the time afternoon tea was served, three hours later, the coast of Ireland was fading from view.33 There were four venues in which first-class passengers could take tea, one of which afforded spectacular views towards the stern.34 The Verandah Café, split into two rooms, one that allowed smoking and the other, particularly popular with mothers and their children, that did not, was located on A-Deck as the furthest aft of the first-class public rooms. Inspired by the “winter gardens” popular on the German greyhounds, the Verandah was lined with bronze-framed windows and green trellises covered in growing plants. White wicker chairs and tables cluttered the room, reminiscent of a conservatory on land. As Ireland melted into the horizon, a passenger who had boarded there went up onto the Poop Deck, the area at the stern used as the promenade for Third Class. There, on his uilleann pipes, an Irish instrument similar to the Highlands’ bagpipes, the young man played “Erin’s Lament” and “A Nation Once More,” paeans to the Irish quest for independence and, in the case of the former, sharply critical of the landed classes.35 It is unlikely that anyone at tea heard him; the doors into the Verandah were designed to stifle a chill breeze and any sounds from the outside.36

I. An early exception was Lady Rothes’s maid, who felt queasy shortly after departure from Cherbourg.

II. Dublin Mean Time was abolished in 1916 after it had caused confusion in relation to reports and reactions to an anti-British uprising in Dublin, generally known later and today as the Easter Rising. Until 1978, France also operated under its own time zone, which was nine minutes and twenty-one seconds ahead of Greenwich Mean Time.