CHAPTER 6 The Lucky Holdup

Eustacia Vye was the raw material of divinity. On Olympus she would have done well with little preparation. She had the passions and instincts which make a model goddess.

Thomas Hardy, The Return of the Native (1878)

AFTER DINNER ON THE DAY the Titanic visited Queenstown, printed copies of her passenger list were delivered to the first-class staterooms, facilitating, for those so inclined, an eagle-eyed hunt for on-board friends, established or intended.I1 Showing only those traveling in First Class, the manifest was printed alphabetically, running in this case from twenty-nine-year-old Elisabeth Allen, returning to her native Missouri to pack up her life in preparation for her forthcoming marriage to a British doctor, through to New Yorker Marie Young, who had once taught music to President Theodore Roosevelt’s youngest, and allegedly favorite, daughter, Ethel, and was returning from her European vacation as a companion to Ella White, she who had sprained her ankle while boarding at Cherbourg.2 Few subsequent accounts of the Titanic’s career agree on her passenger capacity, and the quest for a precise figure is in some sense a fool’s errand. Some of these discrepancies arise from the facts that both First and Second Class had blocks of their cheapest cabins that could, in moments of high capacity, be reassigned to the class below them and that several cabins had room for a cot or child’s bed, adding a further variance.3 Broadly speaking, the Titanic had room for about 900 passengers in First Class, 550 in Second, and 1,100 in Third.4 The lists passed out in First Class on April 11 confirmed that there were 324 traveling in the most expensive part of the ship. Despite the fact that the Titanic is described as fully booked in several dramatizations and popular accounts of her voyage, the reason why Purser McElroy had been able to move the Countess of Rothes with such ease at Southampton was because nearly two-thirds of the Titanic’s first-class cabins were unoccupied. Second Class was about half-empty and Third Class just under two-thirds occupied once the full complement was on board after departure from Queenstown. With 891 crew members, this meant that about 2,208 people were on the Titanic after Thursday the 11th, not allowing for stowaways, if any had avoided the ship’s eagle-eyed officers.

Different reasons for the “Queen of the Ocean” sailing at about 50 percent of commercial capacity have been suggested, with the recent British miners’ strike popularly identified as having caused enough uncertainty in the traveling public that many decided to wait until the coal-dependent steamers were certain to sail.5 Equally possible is the fact that the Titanic sailed in spring, just before the more popular summer season, which might explain the dip in occupancy. Eastward crossings at that time of year, back from New York, also seem generally to have been busier than those westward—a comparison with the Olympic’s maiden crossings a year earlier shows broadly similar numbers with 489, 263, and 561 in the respective classes from Europe compared to 731, 495, and 1,095 for the return trip.6

For John Thayer, a glance at the roster was unlikely to produce too many surprises. The majority of Americans in First Class had, like the Thayers, boarded at Cherbourg via the Nomadic. There was another railway tycoon in Charles Hays, the American-born general manager of Canada’s Grand Trunk Pacific Railway, who was traveling home from a board of directors’ meeting in England in time for the opening of his company’s new railway hotel, the Château Laurier, in Ottawa.7 There was also a healthy number of fellow Pennsylvanians, nearly all of whom were friends of the Thayers, including George Widener and his family, sailing in a C-Deck suite a few doors down from theirs. The Wideners’ money came from banking, which had been used by George as the springboard to a Philadelphia streetcar monopoly, while the bulk of the family fortune remained with his seemingly immortal father, Peter. The richest man on board, by a considerable margin, was Colonel John Jacob Astor IV; his military rank came from his service in the Spanish-American War of 1898, and his $87 million bank balance, broadly equivalent to just over $2 billion in 2019, from being born into a family who owned so much of the city that they were nicknamed “the landlords of New York.”

If the sight of Lady Rothes’s name on the passenger list excited those attracted to the allure of the titled, a similar thrill was generated for devotees of the emerging cult of celluloid celebrity by the name of Dorothy Gibson, sandwiched in the passenger list between her redoubtable mother and Arthur Gee, the British-born manager of a printworks in southern Mexico.8 Dorothy’s most recent movie, The Lucky Holdup, was released in the US and France on the day the Titanic left Queenstown. Ordinarily, Dorothy tried to turn up at her various premieres, the first actor to make a regular habit of doing so, but she had been so busy and successful in recent months that she could afford to skip the promotions for her latest opus. Even to those unfamiliar with the burgeoning movie industry, Dorothy Gibson had made an impression since boarding at Cherbourg the previous evening. Unaware of her name, the Washington, DC–based socialite and author Helen Candee, having spotted Dorothy when they were sequestered on the Nomadic, was almost certainly referring to her when she wrote later of “the most beautiful girl” and perhaps when she recalled the “indispensable American girl.”9 Publicly, Dorothy was self-deprecating about her appearance, but in private a colleague confirmed that she considered it almost a gift from God “by the grace of which she earns an honest living.”10

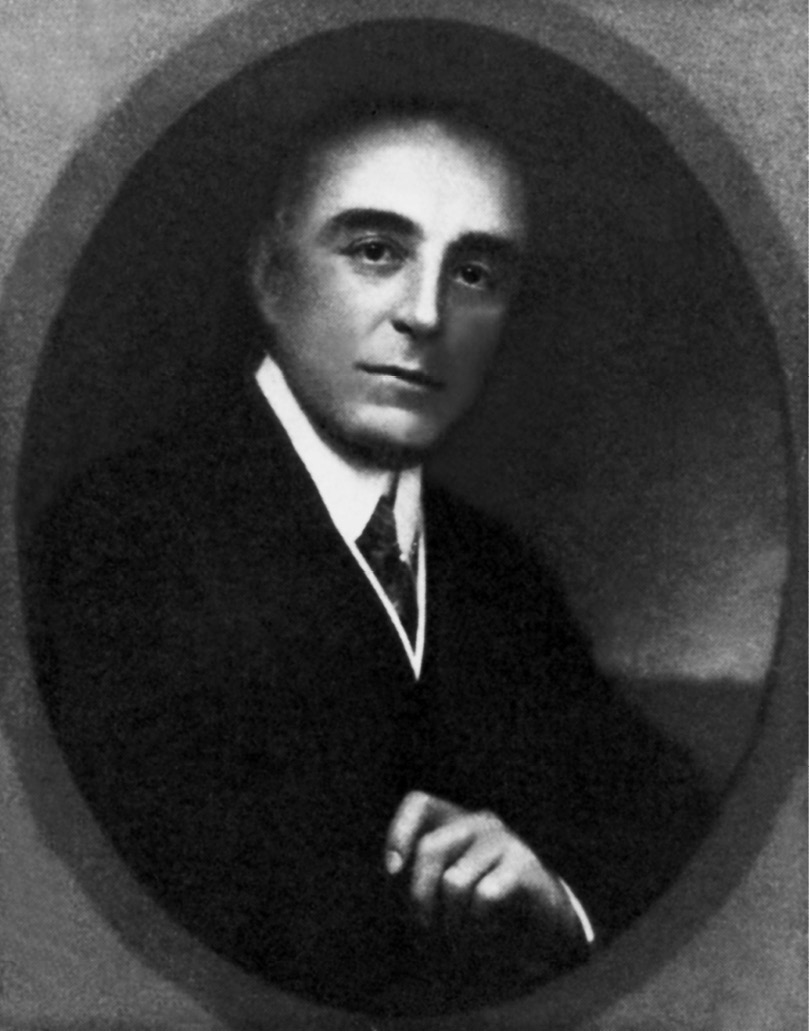

Dorothy Gibson, photographed c. 1911.

To describe Dorothy’s career as “an honest living” implied a humbleness as theatrically misleading as her demure claims regarding her looks. At five weeks short of her twenty-third birthday, Dorothy was one of the highest-paid actresses in the world on a weekly salary of $275, nearly double that of her most prominent competitor, “America’s Sweetheart” Mary Pickford.11 It was, to her relief, an income that had taken Dorothy far from her comfortable lower-middle-class childhood in Hoboken, New Jersey, which, fittingly for a woman who was to forge her first great successes by marketing herself as the “all-American girl,” was also “the birthplace of baseball, the Tootsie Roll and the ice cream cone,” in the charming phrase of one of her modern biographers, Randy Bryan Bigham. Her Scottish-born father, John Brown, had been a contractor until his death aged twenty-five in February 1891, when Dorothy, his only child, was twenty-one months old. Brown’s death certificate gives the cause of death as bronchopneumonia at the family home on Bloomfield Street in Hoboken.12 Almost exactly three years later, his twenty-seven-year-old widow, Pauline, married an Irish shopkeeper, Leonard Gibson, who adopted Dorothy, at which point she was given his surname.13 She was eight when the Kaiser Wilhelm der Große docked in her home city at the end of its first crossing of the Atlantic, and over the next decade the “Hohenzollerns of Hoboken” came and went from a city with a thriving German immigrant community. Dorothy grew into a popular child and teenager, who was praised at parties given by family friends for her beautiful singing voice. In a later interview with a journalist, she claimed, “It was singing that I loved. But I had not the slightest inkling of the stage as a profession. In those days, a girl was expected to act in amateur theatricals for charity but never was she to think of it as an occupation, and I didn’t.”14

This particular claim does not entirely convince when one considers that Dorothy made her Broadway debut at the age of sixteen. Her stepfather, a devout Baptist, insisted that Pauline act as a chaperone at their daughter’s rehearsals and evening performances, a task at which she proved so woefully inadequate that one can only suspect her apparent negligence was deliberate strategy. As a further sop to her nervous stepfather, who had moved the family from New Jersey to New York to launch the career of the allegedly reluctant Dorothy, she initially appeared under the stage name of “Polly Stanley,” which she later misremembered as “Polly Stanton.” Polly Stanley was abandoned in favor of Dorothy’s real name around the time her early vaudeville performances caught the attention of one of the great theatrical producers of the era, Charles Frohman. Sickly, slender, and brilliant, Frohman offered Dorothy a part in The Dairymaids, a show he was then in the process of bringing over from London for its Broadway premiere, which she accepted, landing her first review in the New York Times.

Despite that review’s praise, Dorothy’s professional relationship with Charles Frohman ended after The Dairymaids. Why remains unclear, although subsequent accounts of her career have hypothesized that Frohman’s notoriously obsessive attitude towards the morality of his female actors may have caused the rupture. Dorothy was flirtatious and well liked. The most serious of her beaux was a young pharmacist from Memphis, Tennessee, George Battier, who delivered gifts to her dressing room, something which may not have sat well with Frohman. It did not matter. Her career had already started its upwards swing. On the back of the show’s success, and the compliments of the New York Times, Dorothy was signed by the Shubert Brothers agency, who launched the eighteen-year-old into a manic schedule of theatrical tours throughout 1907 and 1908, and then again in 1909 when she was asked to reprise her role in a comedy titled The Mayor and the Manicure. It was not exactly her Ophelia, but, like her next play, Sporting Days, in Dorothy’s words, “It was a hit.” Her wonderful singing landed her another tour in 1910, this time to Boston and Philadelphia with the Metropolitan Comic Opera Company. She and her mother were thrilled with her success, but she remained refreshingly unpretentious about the kind of plays she was doing. “All we did,” she joked, “was stand around in pretty hats, lean on our parasols and purr through some ditties.” On February 10, 1910, she married George Battier and they moved into an apartment in Manhattan. By summer, she had left him. The religious zeal she admired in her stepfather proved suffocating in her husband, a fervent evangelical who was both possessive and perpetually suspicious of her.

She was back to standing, leaning, purring, and being applauded in A Trip to Japan when there was another knock on her dressing-room door. She remembered that the caller, Harrison Fisher, arrived with no gifts and shook her hand, rather than kiss it. She appreciated that, especially in light of his opening offer of “Miss Gibson, I admire your face. May I paint it?” She laughed, but consented once she realized he was serious. Fisher was already known as “the king of the magazine covers,” and according to Harper’s Bazaar, he was “the greatest portrayer of American womanhood.” His paintings offered the country a fantasy of idealized femininity, full of beautiful clothes in everyday scenarios, by turns playful, alluring, romantic, and doe-eyed. Fisher’s critics characterized his work as so sweet it could induce cavities, but he was phenomenally successful and Dorothy was impressed with his “very gentlemanly and businesslike” attitude towards her. Gossip swirled, then and later, that she and Fisher were lovers, but there is no evidence for that or for most of the other stories in circulation about the pair, such as the deliciously absurd claim that at their first meeting, far from a handshake, Fisher “went down on his knees and begged the lovely Miss Dorothy to come away to his studio so that he might at once commit to canvas her gorgeous features, glorious curves and glamorous youth. She consented and resigned her post on the spot to become Mr. Fisher’s latest muse.”

As she had been with her plays, Dorothy was dismissive about her modeling career, describing the whole thing as “a terrific bore” and joking, “I believe I have a permanent crick in my neck from the strain” of having frozen so often in poses of head-tilting adoration. However, as with her professed nonchalance towards her roles on Broadway, it is difficult to believe that Dorothy was as indifferent as she claimed about becoming one of the most recognizable models in America. She was certainly peeved when other “Harrison Fisher girls” were given precedence over her and incensed when, for one cover, Fisher merged some of her features with those of another model, Rita Rasmussen. Later, she saw the humor in it—she told journalists, “The first picture I recall seeing my features mixed up with hers in was one where I was in furs with a pug dog to my chin”—and she was pragmatic enough to let Fisher ply his trade without too much interference. When he put her on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in April 1911, her face was sent out to over a million readers, and in both June and July of that year she was in radiant isolation on the cover of Cosmopolitan magazine. The June cover became one of her most memorable incarnations—her blue eyes gazed at the unseen artist, her lightened blonde hair was caught up beneath a huge beribboned hat, and she wore a white afternoon gown and sipped sarsaparilla through a straw. It was Americana, in a haute couture hat, and it inadvertently took her back to New Jersey when she received an offer of work from the Independent Motion Picture Company.

It was not, initially, a happy exchange. After the attention she had deservedly received for her work in the theater, Dorothy was surprised and then distressed to realize that her new employers wished to harvest her fame for their advertising, while relegating her to the life of a glorified extra. She signed a new contract with the Lubin Studios in Philadelphia, where the press office twice confused her work with that of another actress on their books with the same surname. The main American movie studios were still on the East Coast in 1911, with the great move west several years off, which brought the Société Française des Films et Cinématographes Éclair to Fort Lee when they decided to establish their first American base. They were already celebrated for their work in Europe, where they had merged highbrow historical pieces with commercial success. Their new studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey, was the largest in the United States, serving as the base for the company’s self-proclaimed mission to “marry the appeal of American acting with French technical mastery.” For their first American-made picture, Éclair hit upon the ingenious idea of producing a costume drama chronicling the founding moment of Franco-American cooperation—Louis XVI’s support for the War of Independence. There was a frenzy of competition among actors to be seen by Éclair, from which Dorothy remained majestically aloof since she had already been offered a contract after securing a private interview with Harry Raver, one of Éclair’s American administrators. She quit her unsatisfactory job at Lubin and left Philadelphia for a larger salary and better exposure.

For its time, Hands Across the Sea was, as described in a review by the Motion Picture News, one of the “masterpieces of motion picture photography and intelligent artistic production.” It re-created for impressed audiences George Washington’s fêtes at Mount Vernon, Benjamin Franklin’s reception by the French Royal Family, and the revolutionary battles of Monmouth, Brandywine, and Yorktown. In an early section of the movie, Dorothy glittered on the screen in jewels, a wig, and a ball gown, cast as the most beautiful noblewoman at Versailles, dramatizing a historical incident when Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette had honored Benjamin Franklin by permitting a court belle to crown the first American ambassador with laurel leaves.15 In the second segment, Dorothy appeared as Molly Pitcher, an iconic if possibly apocryphal American revolutionary war widow who fought at the Battle of Monmouth.16 Elsewhere in the reel, Dorothy played the victim of attempted rape by theatrically villainous redcoats and then a politician’s wife who, wholly fictitiously, catches the eye of George Washington.

Dorothy’s lover, Jules Brulatour.

Hands Across the Sea, sometimes advertised as Hands Across the Sea in ’76, was a triumph both for Éclair and for its star. The movie was still playing to packed houses across the country, with some cinemas requesting extra reels to mount two or three showings simultaneously, when Dorothy accompanied Harry Raver to the Motion Picture Distributing and Sales Company ball in October 1911. What it lacked in a catchy name, the party more than made up for in glamour and amusement. At the ball, Dorothy was introduced to Jules Brulatour, a forty-one-year-old producer at Éclair whom she had not yet had the opportunity to meet. Brulatour was tall with dark eyes and a strong physique. He had been brought up in New Orleans and retained the accent. He also carried with him an unsavory reputation for blackmail and double-dealing in furthering his career, but he could be charming, as he was at his first meeting with Dorothy in the Alhambra’s ballroom. He complimented her on introduction with the remark that he recognized her from her “lovely photo in the papers.” They struck up a conversation and Dorothy lost interest in Raver’s company or anybody else’s. “It was,” she said, “the kind of immediate acquaintance where no one else exists.” Their romance began almost immediately, with discreet rendezvous at the St. Regis and Great Northern hotels in the city.

Somebody else did exist, however, namely Mrs. Brulatour, who had, on the night of the ball, been at home with their three children: sixteen-year-old Marie, six-year-old Ruth, and their four-year-old brother, Claude. Despite the fact that she too was still legally married to the pious Battier, Dorothy was unwilling to accept that her love affair with Brulatour should remain adulterous and covert. During filming for her next picture, a Society-set comedy called Miss Masquerader, she initiated her own divorce proceedings and Brulatour promised he would do likewise, when the time was right. There was no denying that the pair were infatuated. She nicknamed him “Julie,” a teasing pun on Jules, and he called her “Mutsie.” Pauline Gibson knew all about her daughter’s liaison and actively encouraged it; Brulatour had made a fortune in his previous job as a distributor for the Eastman Kodak Company.

It would, however, be wrong to suggest, as some have, that the next stage of Dorothy’s career was simply the result of her affair with Brulatour. She was already established and admired when they met. If anything, the relationship nearly derailed her success. Miss Masquerader was another triumph, with a syndicated column in the Hearst press singling out the comic ability of Éclair’s “new leading lady, Miss Dorothy Gibson,” and she was again compared to Pickford for the naturalism of their performances, eschewing the typical melodramatic gestures of most other silent movie actors, a style which Dorothy seemed to regard as demented puppetry on the part of her fellow actors. More offers came and were accepted. Even accounting for their reduced running length, with many popular films lasting no longer than ten or fifteen minutes, it is hard to fully appreciate the speed with which movies were made, produced, and distributed in 1911 and 1912. Over the course of a few months, Dorothy appeared as a fairy godmother in The Musician’s Daughter, a sweatshop-trapped widow in The Wrong Bottle, wives respectively suspicious of adultery and guilty of it in Mamie Bolton and Divorcons, a down-on-her-luck debutante in Love Finds a Way, wounded love interests in The Awakening and The Guardian Angel, a gambling addict in Bridge, an unlikeable snob in the didactic domestic drama It Pays to Be Kind, and, in art mirroring life, a young woman who falls in love with an older man in A Living Memory. These were followed by a return to her natural strength, comedy, for Getting Dad Married and The Kodak Contest. Her salary had doubled and she was queen of the Éclair lot, hosting numerous parties for the studio’s staff and talent, but by the spring of 1912, when she played a lovelorn cooking teacher in The White Aprons, she was also exhausted. A real shove towards a nervous breakdown came when Jules turned up to one of her soirées with his wife, Clara, as his plus one.

Unraveling under the pressure of a frenetic work schedule and torturously confusing private life, Dorothy’s performance in Brooms and Dustpans was panned as “flat and absurd” by the formerly admiring critics at the Dramatic Mirror. Brulatour, perhaps remorseful for his behavior at the party, was worried about Dorothy’s health, as was her mother. Dorothy arranged another tête-à-tête with her friend and erstwhile boss Harry Raver to impress upon him her need for a vacation. During their meeting, she became so upset that she expressed a seemingly sincere desire to quit permanently. Raver, in a fairly repugnant display of manipulation, promised to release her temporarily from her contract only on condition that she film three more comedies before she left. Victim of a tiredness that had crept into her bones, Dorothy agreed and raced through halfhearted performances in The Easter Bonnet, The Revenge of the Silk Masks, and The Lucky Holdup, the last being a Gilded Age take on Romeo and Juliet, with a happier ending. Brulatour was handling the logistics of her proposed trip to Europe and Egypt, with her mother as a companion, when Dorothy discovered Raver had snuck a fourth movie onto her schedule, the second screen adaptation of Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. She filmed it and left for New York, from which, as the city’s Irish community was celebrating St. Patrick’s Day, she and her mother sailed in choppy weather for France.

No one can know for certain if Dorothy’s journey to Europe was motivated more by her professional or personal considerations. Given her fatigue, it is highly unlikely that she herself could have known for certain. It was later suggested by some of those who knew the couple that, after the embarrassment of the party and his foot-dragging over his divorce, Dorothy engineered the entire trip to reinspire Brulatour’s pursuit of her through pain at her absence. This assessment of Dorothy’s motives seems unnecessarily suspicious, especially in light of her distress at the schedule inflicted upon her by Harry Raver. However, that Brulatour remained Dorothy’s priority is suggested by a telegram he sent to her when, after a week spent in Venice, she and Pauline reached Genoa on Monday, April 8. Although her recuperation was supposed to have lasted months, Dorothy agreed to Jules’s suggestion that she return to New Jersey so they could make a movie together. Her trips to Naples and Egypt were canceled and the Gibson women moved with lightning speed to return to the United States. The journey from Genoa to Paris required at least two trains and one of those overnight, but they had arrived in time for a shopping spree on the Rue de la Paix on Tuesday the 9th and caught the boat train to Cherbourg the following day. On the train journey from Paris, Dorothy told one of her companions that she was “overjoyed” to be traveling home on the Titanic.17

As famous as she was, Dorothy was still part of a nascent industry, and the considerable wealth enjoyed by movie stars was nearly a decade away. A salary of $275 was huge to most of Dorothy’s generation, but not to many of the Titanic’s other first-class passengers. Tellingly, she remained preoccupied with a need for permanent security, for which she looked to marriage and not her career, which she always, perhaps not unfairly, regarded as inherently and terrifyingly unstable.

Dorothy and her mother shared cabin E-22, one of the cheapest rooms available in First Class. The Countess of Rothes’s maid was traveling on the same corridor. Nonetheless, Dorothy was impressed by the Titanic, which she described as “glorious.” The three manned elevators for First Class, running from A- through E-Deck, opened on the latter opposite the ladies’ bathroom since, like most of the Titanic’s cabins, even in First Class, the Gibsons’ room did not have its own lavatory. Sinks were provided in all first-class staterooms, but only a few of the suites on B- and C-Deck, like the Strauses’, had their own private bathrooms. Communal toilet facilities, similar to those in a restaurant, were provided in lieu, and this was to remain the norm in First Class until the arrival in 1938 of a Dutch luxury liner, the Nieuw Amsterdam, after which en-suites throughout First Class came to be expected.18 Accessible from a small corridor within the E-Deck lavatory block were two ladies’ bathrooms, which could be reserved by passing on a request to one’s steward or stewardess, who would in their turn talk to the ship’s bath steward about booking a slot on the passenger’s behalf.19 Immediately around the corner from this block was Dorothy and Pauline Gibson’s two-berth white-paneled cabin, with its oak dressing table, wardrobe, and chest of drawers, over which their porthole looked out to the sea.20 The voyage would offer Dorothy her final few days of rest before she met “Julie” for another bout of filming. At Cherbourg, she had assured a reporter from the Moving Picture News that she felt “like a new woman” and was “so happy at the prospect” of getting back to America that “I couldn’t think.”

Well versed in the hyperbolic politesse of the movie industry, Dorothy had also once assured a journalist, “I am a daughter of Hoboken. There is a pride in that.” Only she, and perhaps her mother, ever knew how much truth there was in that statement. On another occasion, Dorothy contrasted her stepfather’s evangelicalism with her ambition in what sounds like a more frank admission of why she had struck out from the paths expected of a girl from her background in Hoboken: “My father is a great man of the spirit and is contented with the simple life. But I and my mother are bohemians and we find the pleasures of this lovely world irresistible!”21 Whether she would find permanent access to the pleasures of the world through the career she had won for herself or the marriage she wanted remained to be seen.

I. An equivalent list was also passed out in Second Class, although, according to the recollections of passenger Kate Buss, it was not issued there until just after the next day’s breakfast.