CHAPTER 9 Its Own Appointed Limits Keep

Part of the afternoon had waned, but much of it was left, and what was left was of the finest and rarest quality. Real dusk would not arrive for many hours; but the flood of summer light had begun to ebb, the air had grown mellow, the shadows were long…

Henry James, The Portrait of a Lady (1880)

ON SUNDAYS AFTER BREAKFAST, STEWARDS pushed back several of the Dining Saloon’s tables and rearranged chairs for a nondenominational service, led by the Captain since, like most ships at the time, the Titanic did not provide a designated chaplain. Amid the spiritual labyrinth of Protestant denominations, some differences are so slight as to be discernible only to a skilled theologian—Thomas Andrews’s Presbyterianism, for instance, was technically Non-Subscribing Presbyterianism, a northern Irish creedal detour reached via rejection of the Westminster Confession of Faith of 1646, with its most significant theological deviation, the embracing of Unitarian as opposed to Trinitarian theology, making little difference to its everyday forms of worship. Other denominations, however, are sufficiently distinct as to prevent any kind of meaningful ecumenicalism. There was very little by way of similarity between the typical Sunday worship of the Anglican-Episcopalian Thayers and Lady Rothes, and the Baptist services attended by Dorothy Gibson and her mother. However, although the forty-five-minute religious service in First Class was pragmatically nondenominational, it was not nonconfessional.1 It was Protestant. Mass was celebrated in the second-class Library and afterwards in the General Room for Third Class, but it was not typically offered in British passenger liners’ first-class quarters until the 1930s, and it was offered on the Titanic only after a Catholic priest, traveling in Second Class, volunteered his services. Similarly, although kosher food was provided, no form of non-Christian worship was offered in the ship’s public rooms.

Protestantism ringed and, to a large extent, defined the Anglo-American upper classes. There were a few old families in the British nobility, principally the Howard dukes of Norfolk, who had remained Catholic since the time of the Reformation, with their faith regarded either as an eccentric quirk by their Anglican peers or as grounds for disqualifying them from various positions in public service.2 In rare instances, its oddity proved useful; prominent Catholic families in the British and American upper classes were often recruited to serve on diplomatic missions to the Vatican or Vienna.3 However, while many Protestants from a similar background were quite happy to be friends or colleagues with Catholics or Jews, they drew the line at in-laws and there remained a feeling that, when it came to non-Protestants in the elite, they were “not quite one of us.” So long as the outward signs were adhered to, a genuine lack of Protestant faith from those who publicly professed it did not carry the same subtle yet firm social penalties, which explains why Dorothy’s mother, Pauline, had continued her regular attendance at the First Baptist Church of Hoboken, even after both of Dorothy’s younger brothers died in infancy, a double tragedy that had dealt a body blow to Pauline’s faith from which it never recovered. She had gone to church to placate her husband and to maintain her circle of friends, nearly all of whom were active in the spiritual and social organizations of Hoboken First Baptist.4

The two hymns sung in the first-class Saloon on Sunday, April 14, were “O God, Our Help in Ages Past” and “Eternal Father, Strong to Save,” both traditionally associated with the Merchant Marine and Royal Navy.5 The latter is still known in Britain as the “Hymn of Her Majesty’s Armed Forces” and it has since been adopted and adapted by both the US Marine Corps and the US Coast Guard. With its place in maritime tradition, there was nothing unusual about “Eternal Father, Strong to Save” being selected by Captain Smith that morning, but there is something unavoidably haunting in its opening verse:

Eternal Father, strong to save,

Whose arm hath bound the restless wave,

Who bidd’st the mighty ocean deep

Its own appointed limits keep;

O hear us when we cry to Thee,

For those in peril on the sea!6

Ida Straus and her husband were used to Protestantism’s sacerdotal powers of bestowing respectability and demarcation. At the very least, organized Christianity had left a few bruises on the lives of most European and American Jews in the early 1900s. Isidor’s youngest brother, Oscar, had been the first Jew to serve in the US cabinet, as Secretary of Commerce and Labor under the first Roosevelt administration; before that he had been a US Minister abroad, but initial suggestions of postings to Russia or Switzerland had to be rethought in light of the anti-Semitism prevalent in both countries. The Tsar would almost certainly have refused to receive Oscar, and the Swiss government did not give Jewish businessmen or diplomats, even if American citizens, the same rights it extended to others.7 Eventually, Oscar had represented his adopted country at the court of Sultan Abdul Hamid II in Constantinople, where the government under the Caliph of Islam proved more welcoming to a Jewish diplomat than either the Russian emperor or the secular cantons. On North American soil, Isidor’s other brother, Nathan, had been denied a hotel room during a trip to Lakewood, New Jersey, and when Ida’s youngest son, Herbert, applied to join the Triton Fish and Game Club near his Canadian summer home, he was blackballed on the grounds that a previous member had been “objectionable and Jewish” and so they did not want another one.8 The most personally aggrieving slight had come in 1909 when the Strauses’ grandson was rejected as a prospective student by St. Bernard’s Academy. When Isidor, as a former congressman and co-owner of New York’s largest department store, took up his pen to lobby the Manhattan prep school into changing its mind, the headmaster had written back, “I take it as a great compliment that you wish your grandchild to attend St. Bernard’s. Though it is most painful to me, it seems only honest to tell you frankly that we dare not take a child of Hebrew parentage. I cannot say anything in extenuation, except that we have reason to know that we should lose our Gentile pupils were we to accept Hebrews.… The writing of this letter to you gives me real distress.”9

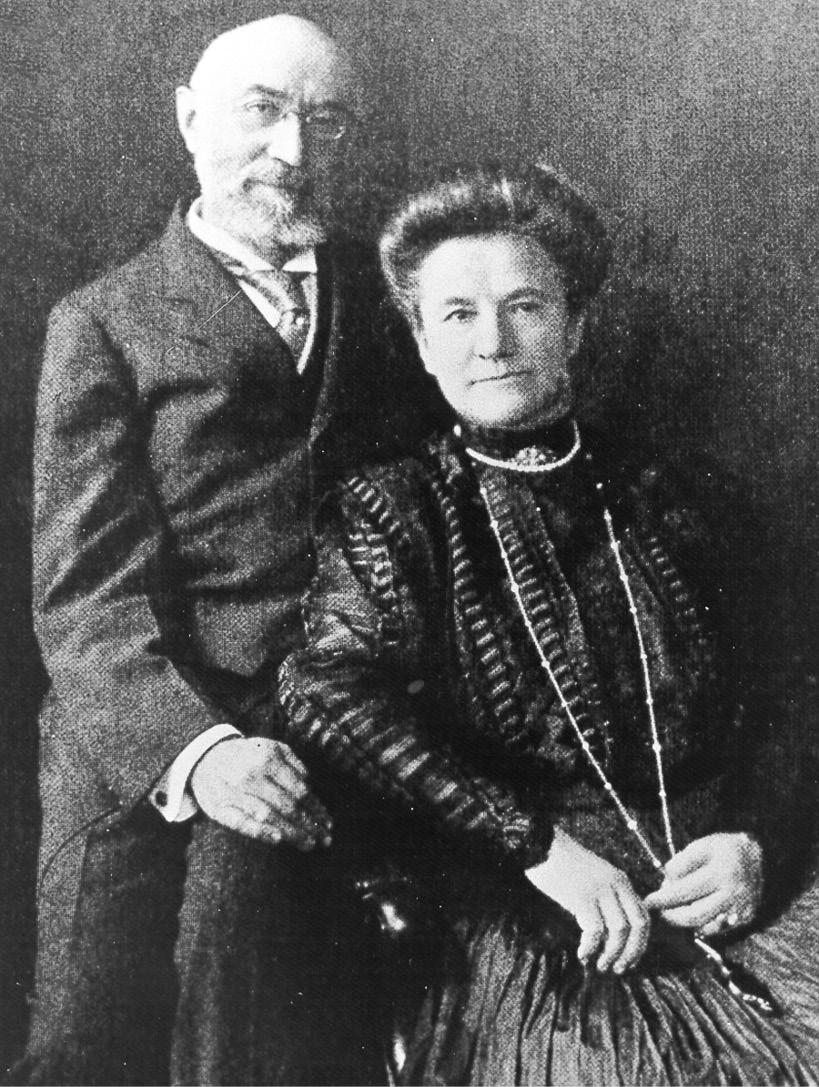

Ida and Isidor Straus, photographed shortly before their trip on the Titanic.

For most of her time on the Titanic, Ida had tried to relax as much as possible. Her heart problem had flared up again that winter, despite the restorative powers expected of the French Riviera, and she had spent much of the voyage thus far indoors.10 Her husband was worried about her and their business. As he had aged, Isidor had delegated more of his responsibilities at Macy’s to their sons, but a renovation of the sixth floor, now offering cheaper goods than the others, had failed to turn a profit, even over the busy holiday season. Their son Jesse was due to take a break from Macy’s to bring his wife and infant daughter, Beatrice, to visit relatives and begin familiarizing the child with European languages. They planned to sail from New York on April 11.11 Rather than have them cancel their trip, Isidor decided to return early to see what could be done with the underperforming sixth floor.12

This change in the Strauses’ schedule may explain the later story that they had originally booked passage home on one of the smaller liners temporarily laid up as a result of the British miners’ strike. However, a letter Isidor wrote to his brother Oscar on March 12 mentions that he and Ida had taken a suite on the Olympic, which was due to make a westbound crossing from Southampton on April 19. Jesse’s impending departure for Germany and concerns about Macy’s apparently prompted Isidor to switch their booking from the Olympic to the Titanic, scheduled to depart nine days earlier, thereby getting them home only two or three days after Jesse and his family left.13 It may have been that the miners’ strike removed from operation certain ships that the Strauses had considered because they had been scheduled to sail even earlier than the Titanic, but the easiest option would have been to switch to another White Star ship, with the Titanic as the obvious choice. The Strauses were in a hurry, if not quite a panic.

Jesse was traveling to Europe on the German liner Amerika, another creation of the Harland and Wolff shipyard and one which was to sail within range of the Titanic’s wireless that Sunday afternoon.14 Passengers could pay at the Purser’s Office to send personal telegrams to shore or other ships, and Ida and Isidor planned to send one to Jesse, Irma, and Beatrice. Until then, they went to the Titanic’s underused Lounge, which had been decorated as an homage to Versailles and was unfortunately sporting a similarly in-keeping feel of an abandoned state apartment.15 No one criticized the appearance of the Lounge, described by a trade journal as “a magnificent salon” and “the finest room ever built on a ship.” In the center of the room, a chandelier nestled in an oval cupola. Armchairs, sofas, and settees with green silk-covered cushions were dotted across the green-and-gold carpet, and there was a small bar that served refreshments.16 However, its location and utility had both been poorly thought out. The chief problem affecting the Lounge’s popularity was that nearly everything it offered to passengers was provided in other rooms on board. Stewards collected letters from its ornamental postbox, carrying them down to the Mail Room for sorting, and there were writing desks, stocked with pens and White Star–headed stationery, but elsewhere on the same deck there was a dedicated Writing Room and the men’s Smoking Room, which likewise contained some desks and supplies for letter writing. Tea was served every afternoon in the Lounge, just as it was in the ship’s two cafés, both of which had better views of the passing ocean, and while the Lounge stayed open late for after-dinner drinks, so did the Reception Room, which had the added benefits of playing host to the evening concerts and dances and of being adjacent to the Saloon, rather than three decks above. The Reception Room had proved popular enough on the Olympic to be expanded on the Titanic, while the Lounge remained of dubious utility and splendid appearance. Its only unique feature was its mahogany bookcase, which functioned as a lending library for first-class travelers and brought the Strauses regularly to the room, along with their friend Colonel Gracie, whom they saw there at about noon, before they sent their telegram to the Amerika and after he had sung and prayed in the Dining Saloon.17 Gracie affectionately blamed the Lounge and its collection of books for his uncharacteristic sloth since leaving Southampton: “I had devoted my time to social enjoyment and to the reading of books taken from the ship’s well-supplied library. I enjoyed myself as if I were in a summer palace on the seashore, surrounded with every comfort.”18 By Sunday, Gracie had been sated by languor and rectified matters by getting up before breakfast to meet “the professional racquet player in a half hour’s warming up, preparatory for a swim in the six-foot deep tank of salt water, heated to a refreshing temperature.”19

Like Ida, the Colonel had boarded the Titanic in a state of fatigue. He had recently completed an enormous work of revisionist military history, The Truth About Chickamauga, a Civil War battle so bloody that the Tennessee river on whose banks it had been fought was briefly renamed “the River of Death.” With 36,000 casualties, two Confederate generals had been suspended for refusing to carry out orders which they claimed would have substantially increased the body count to little tactical advantage. Colonel Gracie’s father had served in the battle and his tome had garnered criticism for its failure to engage honestly with the split in the Confederate command and its strong antipathy towards the Union armies.20 On the first day of the voyage, he had loaned a copy of his book to Isidor Straus, “in which he expressed intense interest,” and Isidor had finished reading it by the Sunday.21 Since renewing their acquaintance during the departure from Southampton, when together they had witnessed the New York incident, Gracie and Isidor had taken daily walks on deck with their principal topic of conversation set by Gracie’s admiring curiosity about Isidor’s “remarkable career, beginning with his early manhood in Georgia when, with the Confederate Government Commissioners, as an agent for the purchase of supplies, he ran the blockade of Europe. His friendship with President Cleveland, and how the latter had honoured him, were among the topics of daily conversation that interested me most.”22 Isidor’s family shared Gracie’s fascination and, the previous spring, Jesse Straus had encouraged his father to write his memoirs, overcoming Isidor’s objections that to do so would be self-indulgent and of limited interest to others.23 Isidor had started the project in June, “jotting down from time to time, as the spirit moved me, such occurrences as happened to present themselves to my mind,” but left the manuscript in New York when he and Ida sailed for Europe in January.24

Decades later, one of Isidor’s grandchildren remarked to a historian that Isidor and the first generation of Strauses to settle in America had lived a life that sounded, to him, like something from “the world of Gone with the Wind.”25 It was not a wholly inaccurate observation. Gone with the Wind provides a backstory for Gerald O’Hara, the fictional paterfamilias, which has him fleeing to the United States after running afoul of an aristocratic agent in his native Ireland. Having been forced across the Atlantic by politics, Gerald initially enters a career in trade, migrating to the southern state of Georgia where, over a game of cards, he wins an unloved plantation and a slave from a drunken opponent. Initially something of an outsider thanks to his Catholicism, Gerald is eventually accepted into the land- and slave-owning classes, who grow to like and trust him; he settles down, buys more slaves, raises a family, and pledges allegiance to the Confederacy when, two decades later, Georgia secedes from the Union. Isidor’s father, Lazarus Straus, came from a respected Jewish family in Otterberg, and he had sided with the uprisings of 1848, a wave of unrest that swept across Europe amid industrial downturn and political frustration. Unlike its Orléanist counterpart in France, the Bavarian monarchy weathered the crisis and retaliated by making life difficult for its former opponents. Later, both Isidor and his brother Oscar believed that this had been the direct cause of their father’s emigration to America. Isidor wrote in his memoirs that “my father, who was active in the revolution of 1848, finding life burdensome after the collapse of the movement, long contemplated emigrating, but his ties were so many that he found it most difficult to tear himself away, and not until the spring of 1852 could he bring himself to take this decisive step,” while Oscar, who was too young to remember the events personally, had been told of “petty annoyances and discriminations which a reactionary government never fails to lay upon people who have revolted, and revolted in vain.”26 However, historians who have written that Lazarus Straus had to move because of the hostility of the Bavarian government are perhaps taking too literally the brothers’ recollections. Of the two accounts, Isidor’s is the more restrained, mentioning only that his father’s life in Otterberg became “burdensome,” while his citation of Lazarus’s responsibilities as an explanation for why he did not emigrate until 1852 suggests that there were various reasons behind the Strauses’ departure. The 1848 revolution had failed in Bavaria, but not completely; the collapse of the uprising did not equate with the simultaneous re-establishment of the status quo. In the immediate aftermath, the previous King of Bavaria, Ludwig I, had abdicated in favor of his son, Maximilian II, who initially attempted to pursue a moderate course between middle-class liberalism and the conservatism of the Catholic clergy and the aristocracy. It was not until 1852, when Lazarus Straus left Bavaria, that the powers of the police began to be increased to their pre-1848 levels and 1859 before the triumph of reaction with the garroting of the electoral laws.27 While life in Otterberg was less pleasant for Lazarus Straus after 1848, there is little in the history of the wider region to suggest he had to leave specifically because of his political views. There was an acrimonious inheritance dispute with several of his thirteen siblings, which may have been one of the “many ties” vaguely remembered by Isidor. The argument seems to have soured relations with his family, making migration a potentially less wrenching prospect than it had been before.28

Lazarus left behind his wife, Sara, and their six children—Karolina, Isidor, Hermine, Nathan, Jakob, and Oscar.29 They were to follow when he had established a home and saved enough money to send for them. From his disembarkation at Philadelphia, Lazarus moved south to Georgia, where he found work as a peddler, an integral part of the nascent American economy through its role in bringing goods to rural homesteads.30 They were particularly necessary in the South, where plantations were often separated by significant distances from the nearest towns and stores. It was his father’s experiences in the antebellum South that permanently convinced Isidor of the virtues of Southern hospitality and that anti-Semitism was both more pernicious and more widespread in the North. He told his own children that their grandfather had been

treated as an honoured guest and his visits were looked forward to with real pleasure. Another feature, which sounds almost like fiction, respecting the relationship between even the wealthiest and most aristocratic families and the comparatively humbler peddler, was the chivalrous spirit of hospitality that refused to take any pay for board and lodging of the man and made only a small charge for the feed of the horses, which gives an idea of the view entertained by the southern people regarding the proper conduct towards the stranger under his roof… [thus] a bond of friendship sprang up which in this part of the country and at this time seems difficult to understand.31

Within two years, Lazarus had saved enough to book passage for Sara and the children to sail from Le Havre to New York, and during the voyage the nine-year-old Isidor was excited to spot two icebergs in the distance.32 The family settled in Talbotton, Georgia, where Lazarus opened a store and made friends.33 Isidor’s subsequent assertion that Jewish immigrants who settled north of the Mason-Dixon Line experienced more prejudice than those who migrated south is supported by most histories of Judaism in America.34 The local Baptist and Methodist preachers were regular guests at the Strauses’ dinner table, where they often discussed the risks of poor translations of the Old Testament from the original Hebrew and asked Lazarus for his help with the language.35 Isidor remembered these meetings with fondness and continued the tradition; by 1912, one of his closest friends was the Episcopalian Bishop of Tennessee, the Right Reverend Thomas Gailor.36 Privately, Lazarus Straus and his youngest son, Oscar, always believed that their acceptance into Southern society owed much to the fact that the family’s white skin trumped any other considerations. The latter wrote in 1922 that Lazarus “was treated by the owners of the plantations with such a spirit of equality that is hard to appreciate today. Then, too, the existence of slavery drew a distinct line of demarcation between the white and black races. This gave to the white a status of equality that probably otherwise he would not have enjoyed to such a degree.”37 Again, their interpretations are supported by the research of later historians like Bertram Korn, who argued that the caste system in the Old South was so immeasurably weighted towards color that “this very fact goes a long way towards accounting for the measurably higher social and political status achieved by Jews in the South than the North.”38

One of the main conversational labors of the preachers who befriended the Strauses was to convince them of the morality of slavery.39 Other German-Jewish immigrants to the region in the 1850s recalled being told that “the peculiar institution” was “not so great a wrong as people believe. The Negroes were brought here in a savage state; they captured and ate each other in their African home. Here they were instructed to work, were civilized and got religion, and were perfectly happy.”40 In his memoirs, Isidor passes over the issue almost in silence; Oscar wrote, decades later, that neither of their parents had truly believed in slavery and that they had first bought slaves after hiring them from another plantation for a season’s work in their home, whereupon the hired slaves begged the Strauses to buy them, since they were treated better by them.41 The Strauses were well known later for their kindness to those who worked for them, which, when set in the context of the brutality frequently experienced by slaves in other households, lends some credence to Oscar’s story. We know that the Strauses taught their slaves a trade, as well as literacy, the latter of which was vehemently opposed by most slave owners.42 Secondly, by the 1850s, choosing to prioritize race over economics even in the face of mounting evidence that slavery was in fact retarding the South’s economy, most Southern state legislatures had tightened legal restrictions on manumission until it was “virtually impossible to free a slave except through stratagem or deceit.”43 Finally, Lazarus Straus’s initial opposition to slavery seems to have been worn down in the course of social interactions in his new home. A process by which he evolved through degrees of acceptance fits with hiring and then “purchasing slaves one by one from their masters” because some begged him not to send them back to their previous owners.44

For Isidor and his siblings, the issue was less complicated. They arrived as children in the antebellum South, where, in Oscar’s words, “as a boy brought up in the South I never questioned the rights or wrongs of slavery. Its existence I regarded as [a] matter of course, as most other customs or institutions. The grown people of the South, whatever they thought about it, would not, except in rare instances, speak against it.”45 Where the family’s later recollection of events is incomplete is in detailing how far their acceptance of slavery eventually went. It seems clear that Lazarus and his wife, Sara, participated in the slave-owning system reluctantly, but on at least one occasion, a teenaged Isidor and his middle brother, Nathan, were sent to represent their father at a slave auction, where they wrote home to inform their parents that they had nabbed a bargain in buying a pregnant slave; the phrase “two for the price of one” danced horribly in the image conjured by the letter.46 By the time the 1860 census was conducted and the rage militaire was sweeping the Southern states, the Strauses have been described as owning thirteen slaves, although on closer inspection the relevant entry for the census seems to be referring to the age of one slave, rather than the overall size of the household.47 Claims of a significant number of slaves by 1860 have been contested on the grounds that Oscar later mentioned that after the Civil War his parents took two of the slaves north with them because they “were too young to look out for themselves, and so far as they knew they had no relatives.” However, that was by 1865, and elsewhere in his memoirs, he mentions several other slaves, including two men who were taught a trade—tailoring for one and cobbling for the other—on Lazarus’s orders.48 It may be that the Strauses’ habit of hiring slaves from other masters explains, at least in part, the discrepancies in recollections about the size of the Strauses’ household.49

The issue of Jewish involvement in the history of slavery, and then in the Confederacy, is a tortured one. Then and now, there were those who questioned how a community composed primarily of first-generation immigrants, most of whom were themselves fleeing varying degrees of state-sanctioned persecution, could have come to support a system of government under which the right to own human beings was presented as an inviolable part of the rights to private property. The Strauses’ experience of being slowly convinced after moving to, or being raised in, a culture that increasingly came to define itself by the need to sustain the institution of slavery and which then, to a very large degree, willed itself into being as a nation and then into battle in order to defend it, was fairly common. There was also a slew of reasons that competed with the defense of slavery as motivation for enlistment in the Confederate armies after 1861. Another Jewish Southerner explained that he had volunteered because he was ashamed of staying at home while his compatriots went off to fight: “I could no longer stand it. I could no longer look into the faces of the ladies.”50 Others felt that the South was their home, it had been invaded, and, regardless of one’s personal views on slavery or any other political dispute with the North, duty required a fight under the banner of “Death before dishonour.”51 There were also those who hoped that Jewish service in the military would prevent the spread of various anti-Semitic tropes from Europe, principally the canard of the “Wandering Jew,” which perversely turned the centuries of diasporas and pogroms on their heads by suggesting that Jews were incapable of true loyalty to a country, as evidenced by the fact that they were always moving from one to another. After the war, the Hebrew Ladies’ Memorial Association for the Confederate Dead justified their foundation, set up to care for the graves of dead Jewish Confederate soldiers, on the grounds that “in time to come, when our grief shall have become, in a measure, silenced, and when the malicious tongue of slander, ever so ready to assail Israel, shall be raised against us, then, with feeling of mournful pride, will we point to this monument and say: ‘There is our reply.’ ”52

With the exception of the latter, none of these reasons was particularly different from the myriad that motivated American Christians to take up arms between 1861 and 1865. Approximately three thousand Jewish Americans fought for the Confederacy, against seven thousand for the Union. As a split percentage, this was similar to that of Gentiles.53 Just as there were anti-slavery Southern Jews who enlisted, several Confederate Christian generals whose families had been in the South for generations but who were themselves opposed to slavery felt that honor required them to fight for their home states. There were rabbis who exhorted their congregations to remember the Exodus and the plagues visited on Egypt for the sins of slave owning; there were also preachers like Rabbi Morris J. Raphall, based in New York, who harangued abolitionists attending his synagogue, “How dare you… denounce slaveholding as a sin? When you remember that Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Job—the men with whom the Almighty conversed, with whose names he emphatically connects his own most holy name—all these men were slaveholders.”54 Across the United States, there were priests, ministers, vicars, and pastors who articulated the same dichotomy among Christians. Moses, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Job were once again woven into sermons, so were Christ, Noah, and St. Paul—the Lamb of God against the obedience demanded of a slave; mercy and free will against proper deference to the law of the land. Where the verses were needed, they could be found, mined, molded, and fired.

It was his service to the Confederacy that first brought Isidor into Ida’s life. The Northern navy had blockaded most of the Southern harbors, slowly strangling a struggling economy and birthing the necessity of blockade-runners, who soon counted Isidor Straus among their number. Aged eighteen, Isidor, explaining to his worried mother that his decision to serve was prompted by “my honor & due respect,” made it out of Charleston on the Alice, a small steamer that carried him to Nassau.55 From there, he sailed to Havana, where he hoped to catch a boat to England and the mills desperate for Confederate cotton. No ships were making the trip from Cuba and so Isidor, pretending to be a Northerner, bought a ticket on the Trent, a ship sailing to New York, where many transatlantic ships would be available to him. En route, the Trent’s occupants heard a garbled report of the Battle of Gettysburg, initially incorrectly relayed to them as a Confederate victory. For Isidor and another disguised blockade-runner, the news “produced such elation on the part of the two rebels on board that we had great difficulty in restraining ourselves from jubilation.”56 They arrived in New York to newsboys shouting on the streets that it was the other American army that had triumphed at Gettysburg and that the Confederate forces under General Robert E. Lee were retreating south. Nearly fifty thousand men lay dead on the battlefield in Pennsylvania and even the victorious Northerners had endured such heavy casualties that the federal government wanted to enforce a draft to replace those lost.57

Since crossing the Atlantic as a young boy, Isidor had been fascinated by the sea and he hoped to take advantage of the opportunity presented by being in New York to sail for England on the Great Eastern, then the largest ship in the world. In the meantime, he called discreetly on old family friends, the Bluns, at their home in midtown Manhattan, where he met their fourteen-year-old daughter, Rosalie Ida, who was nearly always known by the second of her two names. Ida’s elder sister, Amanda, had married a Southerner and they had not seen her since the outbreak of hostilities. Isidor brought news from Amanda and best wishes from his parents, and impressed everyone with his exquisite Southern manners and his maturity, but it was a brief introduction as Isidor changed his booking to a smaller ship, scheduled to leave several days earlier than the Great Eastern. The collective mood in New York in the wake of Gettysburg had taken on an ugly, pained, vicious hysteria. Both the loss of life and the draft had presented different targets for the collective fury. One focus, fairly obviously, was against Southerners and Isidor could not count on his ruse of a Northern identity holding for much longer. Another, perhaps less predictably, was black people, whose liberation was now blamed by some in New York as the cause of the war and, thus, their suffering. Isidor left the city on the same evening that rioters torched a Fifth Avenue orphanage for African American children and lynched black people in the streets.58

The defeat at Gettysburg was followed by a swift progression of disasters for the Confederacy. Vicksburg and Port Hudson fell to the advancing Union armies and, from what was reported in the British press, Isidor was sufficiently well informed to predict by the autumn of 1863 that the South would lose the war, with both the Confederacy and slavery vanishing in consequence. He was also well versed enough in history to appreciate the chaos that would ensue in the wake of societal disintegration. On November 14, 1863, he wrote a letter home in which he advised his family to “buy real estate, land, houses and lots. Don’t buy shwarze,” a Yiddish word for black people.59 Not everyone in the Confederacy seemed to appreciate the reckoning approaching with each new defeat. Brutality against slaves actually increased as the new republic unraveled. One particularly hideous anecdote among hundreds came from a Georgian general who told his wife that after he had caught one of their slaves attempting to steal some food, he had personally inflicted the sentence of four hundred lashes. “Mollie,” he wrote, “you better believe I tore his back and leg all to pieces.”60

Southern Jews too now found themselves the objects of collective prejudice. This was not exclusively from their Confederate compatriots. After a slew of victories, the Northern General Ulysses Grant issued a notorious order expelling all Jews from the military district under his command in Mississippi, Kentucky, and Tennessee, claiming that Jews in the Northern-occupied areas were still trading with the Confederacy and that “Jews, as a class, [are] violating every regulation of trade established by the Trade Department.”61 The order was rescinded only when the Jewish community in Paducah, Kentucky, invoked the protections of the Constitution through representatives they sent to speak directly with President Lincoln in Washington.62 While General Grant punished Southern Jews for their alleged loyalty to the Confederacy, some in the South condemned them for supposed disloyalty. As the Confederate economy imploded and it became impossible for even blockade-runners to get in or out, profiteering became a plague and then a target for public dissatisfaction. Rather than acknowledge it as a region-wide problem, several Southern communities insisted that it was a uniquely Jewish crime, including the Grand Jury of Talbot County in Georgia, where the Straus family lived. They issued a presentment lambasting Jews for their “evil and unpatriotic” activities. Since Lazarus Straus was the head of the most prominent Jewish family living in the town of Talbotton, where the statement had first been published from the local courthouse, he took it as a personal insult. He sold his shop and announced his intention to move. Isidor, stranded in Europe with other Confederate blockade-runners, only heard what happened later, recounting how the leading figures of Talbot County had assured Lazarus that they did not mean him, or any Jews they knew personally, and that they were distressed by his plan to leave:

Father’s action caused such a sensation in the whole county that he was waited on by every member of the grand jury, also by all the ministers of the different denominations, who assured him that nothing was further from the minds of those who drew up the presentment than to reflect on father, and that had anyone had the least suspicion that their action could be so construed, as they now saw clearly it might be construed, it would never have been permitted to be so worded.63

Their entreaties did not convince and by the time Isidor could return to America he found his family stranded at their new home in Columbus, Georgia, which they had moved to in time for the area to become part of the region desolated by the Union armies’ 1864 “March to the Sea” through Georgia.

Although he always retained fond memories of his childhood in the South and its sense of community, Isidor never publicly indulged in nostalgia for the Confederacy after its final collapse in April and May 1865. By 1912, there were millions who did, Colonel Gracie being one of them. A school of historiography had arisen in the 1890s, first called the Objectivist movement and later the more revealing Reconciliationist approach.64 Proponents of this interpretation of the recent American past objected strongly to the idea that the Confederacy was a republic christened by the tears of slaves and sustained by their blood. They underplayed both the necessary savagery of slavery and its importance as a motivating cause for secession. Instead, the South was presented as having been the custodian of the legacy of 1776, when the thirteen original colonies had seceded from the British Empire in objection to a central government felt to be unjustly expanding its authority. The “Lost Cause” developed and gained traction, depicting the Old South as an agrarian civilization doomed to collapse in the face of brute, industrialized Northern might. It inspired the erection of hundreds of rapidly produced monuments to Confederate warriors in public places, coinciding with the judicial strengthening of racial segregation in the South under the misnamed doctrine of “Separate but Equal.” The Confederacy had become more enduring and successful in death than it ever had in life.

The only key tenet of the “Lost Cause” myth to be rehabilitated by modern historians has been its depiction of the postwar South as an economic wasteland.65 On his return from Britain, Isidor gradually took over their businesses from his father, who insisted the family work themselves to the point of exhaustion to raise enough money to settle their prewar debts with Northern firms in New York and Philadelphia, most of whom had given up on ever receiving payments from those trapped in a scorched economy. The Strauses’ actions were so admired that they never had subsequent problems securing credit; if they could pay back a loan after backing the losing side in a civil war, they could presumably be counted upon in most other circumstances. Isidor’s trips to New York brought him back into regular contact with Ida Blun, who became “as good a wife as ever man was blessed with” in a wedding at the home of Ida’s parents on July 12, 1871, with their ceremony delayed by riots between Manhattan’s Irish Protestant and Irish Catholic communities, which claimed the lives of thirty-two rioters and two police officers.66

As Isidor moved his parents and siblings to New York, worked for, befriended, and bought out at his retirement the owner of Macy’s department store, served as a Democratic congressman for the state’s 15th district, became a political confidant to President Grover Cleveland, and bankrolled his brother Oscar’s burgeoning diplomatic career, Ida became the mother of seven children between 1872 and 1886—Jesse, Clarence, Percy, Sara, Minnie, Herbert, and Vivian.67 Her greatest heartbreak came in 1876 when her second son, Clarence, died in her arms, shortly before his second birthday; years afterwards, his father concluded that the cause had been undiagnosed appendicitis.68 Ida took great delight in her family, particularly their holidays, and when she and Isidor were apart they wrote to one another daily. After a fishing trip with their son Percy, during a summer when Isidor was serving as a congressman in D.C., Ida wrote to her husband, “I with my own hands landed six trout. I am very proud of my achievement as I have to the best of my knowledge and belief broken all former records of ladies fishing. We remained all day and of course lunched out. This is one of the best parts of the fishing or of the excursion.”69 When their children had grown up and married, they were all invited to dine once a week at their parents’ homes with their respective spouses and children.70 Ida also acquired a reputation in New York as a consummate hostess, who frequently invited to her dinner parties people whose achievements she had read about and been impressed by. One guest was Virginia Brooks McKelway, a graduate of the 1899 Women’s Law Class of New York University, who thought Ida’s “hospitality was marked by generosity and elegance rather than by great elaboration. At her board one met with the finest minds of the day, people interested in the things which stand for progress, both Jew and Gentile.”71 Another invitee, who became a close friend, was Julia Richman, first female District Superintendent of Schools for the Lower East Side.72 Isidor, who had insisted his daughters receive the same level of education as their brothers, supported Ida’s friendship with Richman and her subsequent fund-raising for local public schools.

In one of his letters to Ida, he gently urged her to “be a little selfish; don’t always think only of others.”73 They were one of New York’s most prolifically generous couples when it came to charitable donations. The Strauses had helped fund the foundation of the Recreation Rooms and Settlement to alleviate the impact of poverty in Brooklyn; Isidor sat on the board of the Montefiore Home for Chronic Invalids and the Manhattan Hospital. He aided organizations that provided low-income loans to working-class applicants. He and his brothers supported the Hebrew Orphans Society; he advised the Federation of Jewish Farmers of America, funded Jewish cultural organizations, joined a fund-raising committee to erect a memorial to New York firefighters who lost their lives in the line of duty, and he served as treasurer of the Clara de Hirsch Home for Working Girls in Manhattan.74 The New York Times estimated their wealth in 1912 at around $3.5 million, although a later article in the Atlanta Constitution put it at $4,565,106.75 Isidor had set a significant sum of money aside in his will for Ida and the children, as well as earmarking which charities various sums should be distributed to. Of those latter bequests, by far the most substantial went to the Educational Alliance, which Isidor had cofounded in 1889.76 The Alliance sought to provide shelter, education, and English-language lessons for Jewish immigrants to America, and its work quickly became a passion of Ida’s, as well as fueling a mounting sense of anger at the injustice she witnessed. The intensification of Ida’s political awareness, and an eventual sea change in contemporary American attitudes towards both mass immigration and Jews, stemmed from the assassination of Tsar Alexander II of Russia in 1881. Like Captain Smith’s supposed last voyage, a story sprang up that the pro-reform Tsar had been en route to grant Russia its first democratic constitution when he was killed. In reality, he had been returning from a military revue.77

The anti-monarchist bomb thrown at the feet of the “Tsar-Liberator” ushered him off the political stage and, instead of inspiring the revolution hoped for by the assassins, replaced him with his ultra-conservative son, Alexander III. Much was made later of the Grand Guignol of Alexander II’s final moments as an explanation for the ensuing reaction. Carried dying into his study at the Winter Palace, the Tsar had been surrounded by relatives jolted from their everyday routines—his wife appeared in her negligee; his eldest daughter-in-law arrived carrying a pair of ice skates. Convinced that the assault on the Emperor presaged a wave of similar attacks against other members of the Imperial Family, the grand duchesses refused to be separated from their children, with the result that they too were ushered to his deathbed, remembering for the rest of their lives how “large spots of black blood showed us the way up the marble steps” to the study, where they were left clutching each other in terror.78 The future Nicholas II, then the thirteen-year-old Grand Duke Nicholas, stood shaking in his schoolroom sailor suit, watching his grandfather hemorrhage to death in front of him. The family’s chaplain performed the last rites, while the soon to be Tsar knelt down to hold his father’s hand until he passed.79 It was a wretched scene that permanently hardened the attitudes of several of the Romanovs towards revolutionaries, and even liberals, as “mindless malefactors who… won’t be satisfied by more concessions, they’ll become crueller.”80 However, any attempts to identify Alexander II’s death as either reason or justification for Alexander III’s policies towards his Jewish subjects is a hopelessly naive, or equally disingenuous, piece of revisionism. Long before the assassination, the man who became Alexander III had been the acknowledged head of the reactionary clique at the Russian court and he had vehemently opposed his father’s tentative steps towards constitutionalism. One courtier attempted to square the circle of how Alexander III, “an excellent husband, a loving father, an economical and conscientious master of his house,” could simultaneously be “almost impervious to counsel and opinions of other people,” as well as callously indifferent to the suffering of those he deemed unworthy of sympathy.81 He was not impervious to the counsel of his former tutor, Constantine Pobedonostsev, a devout Orthodox Christian, “so honourable and pious that he makes no secret of his bigotry,” who distrusted Protestants, disliked Catholics, hated democracy, and loathed Jews.82 Dry, petty, and dour enough to have allegedly provided inspiration for Tolstoy’s Alexei Karenin, Pobedonostsev had an impact on Russian life that was uniformly negative, as was Alexander III’s decision to entrust to him the management of both the Russian Orthodox Church and his eldest son’s education. From Pobedonostsev, Alexander III had learned to be a ferocious anti-Semite, and, as a fish rots from its head, anti-Semitism, already energetic in Imperial Russia, took on a new vigor thanks to the Tsar’s undisguised attitudes. Within a year of Alexander III’s accession, 225 Jewish communities in the Russian Empire had been targeted in pogroms. Twenty years later, Jewish leaders admitted they could no longer keep count.83 In the margins of government reports detailing the violence of the pogroms, Alexander III scribbled, “Yes, but we must remember that people are entitled to feel anger to those who crucified Our Lord and spilled His precious blood.”84 The new reign was marked by economic rejuvenation, massive foreign investment in Russian industries, and resurgent nationalism that limited the rights, language, and culture of the empire’s Finns, Ukrainians, Poles, Letts, Lithuanians, and Estonians and brutalized most of its Jews.85 A particularly horrifying policy was enacted after the Tsar appointed one of his younger brothers, the Grand Duke Sergei, as Governor-General of Moscow, who ordered the city’s Jewish residents to label themselves in preparation for deportation. Jewish women who had married Muscovite Christians and begged for permission to stay with their husbands were told they could do so only if they legally reregistered themselves under the classification of prostitutes. Rewards were offered for those who betrayed any Jews in hiding. The Grand Duke temporarily halted the expulsions when stories circulated of hundreds of Jews collapsing in the December snows as they waited for the chartered trains to take them out of Moscow. The deportations resumed in the spring. There were spikes in anti-Semitism elsewhere in the Old World, most prominently with the resurrection of the Blood Libel by Christian and Islamic communities in Syria, but nothing influenced the wave of emigration to the United States as heavily as the policies of Alexander III, most of which survived his death from kidney failure in 1894.86

Many of the eastern European Jews arrived in New York poverty-stricken, uneducated, and traumatized. Isidor, who during his career as a congressman had campaigned for English to be recognized as the official language of the United States, was a champion of assimilation and he prioritized funding educational programs for the new arrivals. Ida shared her husband’s beliefs, as well as focusing on establishing and funding orphanages and women’s shelters. The stories told of the pogroms, particularly by those who escaped the Ukrainian cities of Kiev and Odessa, were chilling and they took a toll on both Ida’s physical health and her mental well-being. She was incensed by Tsar Nicholas II’s failure to protect his Jewish subjects, and in the summer of 1910 she wrote an open letter to him in the form of a poem, “To the Czar: A Prophecy,” which was first published anonymously in the New York Times on September 11:

How canst thou face thy Maker, how canst thou even dare

With all the guilt upon thy head to turn to Him in prayer?

Thou rearest thy religion to cloak thy evil deeds,

The tortures thou inflicted on those of other creeds,

The exilings, the pogroms, the persecutions all,

Thou plannest with thy minions, within thy palace wall.

To thy corrupt officialdom, thou givest a free rein

To murder, pillage, harass thy subjects for its gain.

With olden-time barbarity, with cruelty unsurpassed,

Thou rulest o’er an Empire, so wonderful, so vast,

Whose boundless wealth lies buried for ages, ’neath the soil,

Whose undeveloped resources wait but for honest toil,

While sore distress and famine go stalking in the land

All enterprise, initiative, stayed by a tyrant’s hand.

Bright shines the torch of progress in every land but thine,

Illuming every pathway that leads to Freedom’s shrine,

In thy realm superstition and ignorance hold sway,

Grim allies of oppression that darken every way;

That foster crime and vices of all the vilest sort

And make of human beings a beastly dangerous horde,

Thou art a shame, a byword among the nations all,

Thy subjects’ executions hang o’er thee like a pall!87

…

The influx of these immigrants did not excite sympathy in everyone. Anti-Semitism increased in America, alongside nativist opposition to mass immigration.88 For some American Jews, including Isidor’s brother Nathan, this was a sign that the historical dangers they had escaped in Europe were slowly following them to the United States and thus proof that only the creation of a specifically Jewish homeland could offer permanent safety. When he visited Isidor and Ida at their hotel on the Riviera a few weeks before they boarded the Titanic, Nathan had been on his way to Jerusalem to view both the progress of various charities he had established to help the local poor during previous visits and to research Zionism, accompanied by Dr. Judah Magnes, whose zeal had recently resulted in him being ousted from Temple Emanu-El on the Upper East Side to take over as rabbi for the more conservative congregation at B’nai Jeshurun.89 Nathan and Dr. Magnes tried but failed to convert Ida and Isidor to their way of thinking. A few months earlier, Isidor had explained their opposition on the grounds that:

I look upon Zionism as a dangerous dogma for us in this country. If the new immigrants who arrive here by the hundreds of thousands during the course of a few years, and of whom the Educational Alliance is trying to make good American citizens, are met with the dogma that this country is only a tarrying ground for an ultimate home in Palestine, it places in the hands of anti Semites, as well as those who are opposed to immigration, a weapon which can be used.… Zionism is incompatible with patriotism.… If Zionism means a home for the Jews, I am radically opposed to it. If it simply means a spiritual hope for the oppressed and persecuted people of Russia, Roumania, and Galata, then it is a different proposition. But political Zionism, or Zionism in shape, manner or form, as propaganda in this country, I have no patience with, and I am utterly and irrevocably opposed to it.90

Unlike Nathan, Isidor was not particularly religious. Comments made towards the end of his life, in which he expressed support for a guiding spiritual morality over the strictures of organized religion, suggest that his beliefs may have lain closer to deism than Judaism, and unlike Ida, who had noted that their London hotel did not offer matzoh for Passover, Isidor had not kept to a religiously based diet since he left Germany as a child.91 More important, however, in explaining their hostility towards Zionism was the phrase that appears frequently in Isidor’s correspondence in the 1890s with President Cleveland: “The American people are good people.”92 The Strauses believed, passionately, in America, and their lives are fascinating windows into episodes that nurtured, divided, brutalized, traumatized, and revitalized their adopted country. They trusted in America’s capacity to renew itself and to offer safety from the extremism they had seen damage so many lives in Europe. In a letter to their children, Isidor mentioned Nathan’s support for Zionism, while insisting that a difference in opinion should not lead to a rupture among friends or family: “None of us is perfect and we can always detect little shortcomings in others more quickly than we will recognise greater ones in ourselves. Difference of opinion will arise between thinking persons. Whoever may have been right should not exalt [sic] and taunt the other for having been wrong.”93

Ida (FAR LEFT) and Isidor (FAR RIGHT) celebrating their silver wedding anniversary in 1896, with their children. Isidor’s father, Lazarus, is seated in the center.

Above all, there is no doubt that Ida and Isidor loved one another. Before they left for their vacation in Europe, a friend had noticed that Ida still darned Isidor’s socks, despite their wealth. “If you had a husband like mine,”94 she had apparently replied, “you would do far more than this for him.” Colonel Gracie, whose marriage had suffered since his eldest daughter was killed when elevator cables snapped in 1903, envied and admired the Strauses for the happiness they still took in each other and their children. When he saw them later in the afternoon of Sunday, April 14, a few hours after their earlier rendezvous in the Lounge, Ida told him that they had sent their telegram to their son, daughter-in-law, and granddaughter on the Amerika. Telegrams were generally encouraged to be kept short, so the Strauses had opted for “fine voyage fine ship feeling fine what news,” to which they received a cheering reply.95 Jesse’s message to his parents was the first of two telegrams sent from the Amerika to the Titanic that day. The second, between the respective captains, informed the Titanic that, like the ship that had carried Isidor to the United States in 1854, the Amerika had passed “two large icebergs.” The Titanic’s wireless operators dutifully relayed the warning to other ships in the vicinity and transcribed one from the Baltic, which they delivered to the Bridge.96