CHAPTER 14 Vox faucibus haesit

Entreat me not to leave thee, or to turn from following after thee; for whither thou goest, I will go…

Ruth 1:16

THE COUNTESS, HER MAID, AND Gladys Cherry did not go into the Lounge and obeyed the Captain’s earlier request to them that they congregate on the Boat Deck, where they again heard the din created by the ferocious screams from the forward three funnels as the safety valves attached to the Titanic’s boilers continued to release steam from below.1 “The noise when we got up was appalling,” Noëlle wrote, an assessment supported by one of the Titanic’s officers who compared the roar from the funnels to “a thousand railway engines thundering through a culvert.”2 From where they stood, the Countess, like Jack Thayer on the opposite side of the deck, saw white distress rockets streak hundreds of feet into the sky above her.3 The bellowing of the funnels finally stopped as her party were marshaled into lines by Second Officer Charles Lightoller in preparation for loading lifeboats 6 and 8.4 By this point, it is possible that the Countess, at least, had begun to appreciate something of the seriousness of the situation, since Cissy had apparently also heard and repeated the rumor about the flooding in the Squash Court.5

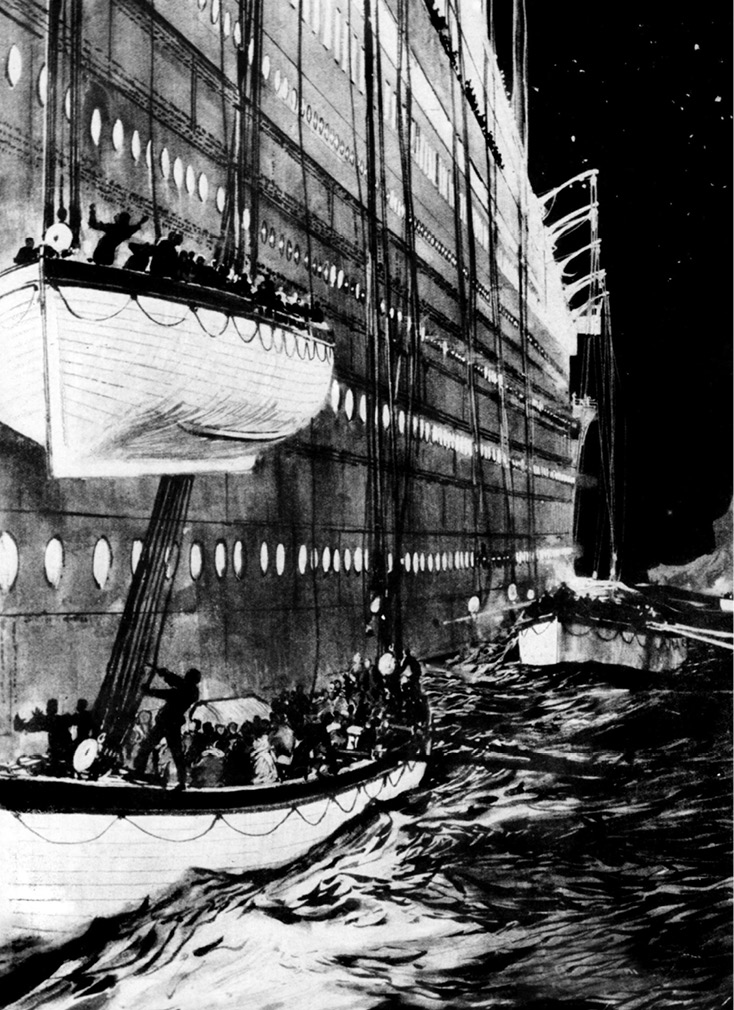

The Titanic’s Lifeboat 8 is in the foreground. It was here that Ida Straus and the Countess of Rothes gathered for the lowering of lifeboats 8 and 6, which was behind 8 but is out of sight here.

Lightoller’s stringent application of “the rule of the Sea” to evacuate women and children inspired panic in the couples standing near the Countess, including a pair she recognized as the Spanish newlyweds, Victor and María-Josefa de Peñasco, whose cabin had been on the same corridor as Noëlle’s. Realizing “they could not speak any English & were terrified,” Noëlle stepped out of line for the lifeboat to talk to them, correctly guessing that they might have a mutual language in French, which Peñasco used to beg Noëlle to “take his wife with me.” María-Josefa clung to her husband, her terror morphing into a hysteria she could not control. Perhaps it was the sight of the distress rockets that explained the shift in mood, a perceptible shaking of certainty, prompting another woman, next to the Countess but unknown by her, to turn away from the boats at the last minute saying, “I’ve forgotten Jack’s photograph and must get it.”6 Whoever she was, Noëlle did not see her again and her attention was soon taken by the Captain, who she thought “looked to be under a terrible strain.”7 As they were loading the lifeboat, Smith told the occupants to “row to the steamer whose lights we could see & leave our passengers & return for more.”8 Both Lady Rothes and, later from a different vantage point, Marian Thayer saw the mastheads of a much smaller vessel on the horizon. It turned out to be a British cargo ship, the Californian, which had turned off her wireless for the evening and whose crew had embraced permanent timidity in dealing with their draconian commander, Captain Stanley Lord. Either missing or misinterpreting the Titanic’s rockets from a distance, they decided there was no point in waking Lord from his slumber, and the scale of their “reprehensible” mistake did not become clear until the next morning when they turned their wireless back on for the day.9

As she got into the lifeboat, Lady Rothes heard Ida Straus say from the deck, “I am not going without my husband.”10 Her account makes no mention of the anecdote recounted in the New York World five days later that Ida’s foot was already in Lifeboat 8 when she turned to ask, “Aren’t you coming, Isidor?”11 The Countess, who was only feet away from Ida, wrote that “tho’ we all begged her to get into the Boat, she refused & went back to join her husband.”12 The Strauses’ friend Colonel Gracie was one of those who tried to persuade Ida to join the ladies in the boat, but “she promptly and emphatically exclaimed: ‘No! I will not be separated from my husband; as we lived, so will we die together’; and when he, too, declined the assistance proffered on my earnest solicitation that, because of his age and helplessness, exception should be made and he be allowed to accompany his wife in the boat. ‘No!’ he said, ‘I do not wish any distinction in my favor which is not granted to others.’ ”13 There are several variations on Ida and her husband’s responses, none of which deviate from her refusal to leave him and his refusal to violate his honor by stepping into a boat ahead of other male passengers.14 Several survivors heard her say to Isidor, “We have lived together for many years. Where you go, I go.”15 It may be that Ida’s heart problems and Isidor’s poor health helped influence their decision not to take a place in the lifeboats. Then again, it seems obtuse to miss the most obvious point and the one articulated by Ida: they did not want to live without one another. First-class passenger May Futrelle, standing nearby and likewise refusing to part from her husband, reported that on other occasions that night, when husbands had begged their wives to go, crew members had physically wrestled the women into the lifeboats: “It appears the officers let the husbands decide that point. Straus was the only one who chose to let his wife stay. We had watched them on the boat and noticed what a sweetly affection[ate] old couple they were. He did the highest thing he knew to let her die in his arms, and it was sweet and beautiful according to his lights.”16

Lady Duff Gordon, who survived the sinking, was openly contemptuous of the rules obeyed by the Strauses and others that night. When her husband, Sir Cosmo, was denied entry to the lifeboats on Lightoller’s watch, she refused to leave the Titanic without him, and so they crossed to the other side of the ship, where Murdoch allowed them to get into Lifeboat 1. In her memoirs, written twenty years later, Lady Duff Gordon claimed that she remained “filled with wonder at nearly all the American wives who were leaving their husbands without a word of protest or regret, scarce of farewell. They had brought the cult of chivalry to such a pitch in the States that it comes as second nature to their men to sacrifice themselves and to their women to let them do it.”17 It was a markedly unkind assessment of the Titanic widows, especially since many of the wives who stepped into the majority of lifeboats trusted in the reassurances of the crew and their fellow passengers that this was a temporary rather than a permanent farewell. Lady Duff Gordon also had an ax to grind in rubbishing the concepts of honor adhered to by Isidor Straus, principally because her husband’s life had been haunted by accusations that he ought to have drowned on the Titanic.18 This was a charge that plagued many male survivors, several of whom were accused of dressing as women in order to facilitate their escape.19 Even today, the Toronto home of Major Arthur Peuchen, who left the Titanic at the request of an officer by scaling down a sixty-five-foot rope to help an undermanned lifeboat, is still frequently referred to as the house of the “man who should have drowned on the Titanic”; there were also colorful stories that he donned women’s clothes to get into a boat.20 There is only one recorded incident of a man cross-dressing, or something akin to it, while leaving the Titanic—Daniel Buckley, a young third-class passenger who had boarded at Queenstown and who jumped into a lifeboat during the later stages of the sinking. At that point, a first-class lady gave him her shawl to wear and told him, “Lay down, lad, you are somebody’s child.”21

In the aftermath of the sinking, the playwright George Bernard Shaw entered into a war of words with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, via printed letters to one another in a national newspaper, about the nobility of the Titanic’s evacuation procedure. Shaw poured scorn on what he saw as the mawkish celebration of a policy that had resulted in the needless deaths of dozens, if not hundreds, of men:

What is the first demand of Romance in a shipwreck? It is the cry of Women and Children First. No male creature is to step into a boat as long as there is a woman or child on the doomed ship. How the boat is to be navigated and rowed by babies and women occupied in holding the babies is not mentioned. The likelihood that no sensible woman would trust either herself or her child into a boat unless there was a considerable percentage of men on board is not considered. Women and Children First: that is the romantic formula. And never did the chorus of solemn delight at the strict observance of this formula by the British heroes on board the Titanic rise to more sublime strains than in the papers containing the first account of the wreck by surviving eye-witness, Lady Duff Gordon. She described how she escaped in the captain’s boat [sic]. There was one other woman in it, and ten men: twelve all told. One woman for every five. Chorus: “Not once or twice in our rough island history,” etc. etc.22

For Shaw, it was the apogee of a lethal idiocy that compelled the male passengers to stand back while boats left half-empty, when no other women or children were present on that part of the deck. All subsequent praise for the men’s actions was, to Shaw, hagiography to hide futility. For Conan Doyle, Shaw’s rubbishing of the sacrifices was proof that “his many brilliant gifts do not include the power of weighing evidence; nor has he that quality—call it good taste, humanity, or what you will—which prevents a man from needlessly hurting the feelings of others.”23

Finally accepting that Ida Straus would not go without Isidor and that Isidor would not go, “several male passengers lifted Miss Bird into the boat.”24 Ida removed her life belt to take off her fur coat, which she handed to her maid with the words, “I won’t need this anymore. You take it.”25 Ellen Bird was helped into the lifeboat, “which was lowered with all haste.”26 As it prepared to go, a gentleman handed his address over to the Countess and asked her to contact his family in Torquay if he did not make it, and Victor de Peñasco dragged his sobbing wife to where Gladys Cherry and Lady Rothes were sitting and “threw her in our arms,” repeating his request that they take care of her.27 Two days afterwards, Gladys wrote that “the lowering of that boat 75 feet into the darkness seemed too awful, [and] when we reached the water I felt we had done a foolish thing to leave that big safe boat, but when we had rowed out a few yards, we saw that great ship with her bow right down in the water.”28 The settling forward as the Titanic was slowly dragged under was far more obvious when seen from the lifeboats than it was to those still on board. Gazing back at the Titanic as their lifeboat rowed away in the direction of the apparent light of another ship’s masthead, the occupants could see that the water had risen far enough to cover up the Titanic’s name on her bow.29

Over the course of the next hour, there were several further attempts to get Ida Straus into a lifeboat. At some point between 1:00 and 1:30 a.m., May Futrelle “saw Mrs. Straus clinging to her husband Isidor, the New York banker [sic]. I heard her say to an officer who was trying to induce her to get into a boat: ‘No, we are too old, we will die together.’ ”30 The disgraced British investment banker Hugh Woolner, who helped escort women to the lifeboats until just after 2:00 a.m., remembered “a very handsome old gentleman, Mr. Isidor Straus, and his wife were there and declined to be separated and when we suggested that so old a man was justified in going into the boat that was waiting, Mr. Straus said: ‘Not before the other men.’ His wife tightened her grasp on his arm and patted it and smiled up at him and then smiled at us.”31

One anecdote about the Strauses, in keeping with their character yet suspect nonetheless, comes from second-class passenger Imanita Shelley, who had spent most of the voyage complaining of how cold her cabin was and of how her health had been damaged in consequence. Imanita Shelley was a voracious social climber, widely disliked and so dense that after she had been rescued from the Titanic’s lifeboats she “took pains to inquire of steerage passengers as to whether or not they had heat in the steerage of the Titanic.”32 Mrs. Shelley claimed that as she and her mother were being escorted to the boats with the other second-class passengers, the Strauses, who had heard of her illness, “met them on the way and helped them down to the upper deck, where they found a chair for [Mrs. Shelley] and made her sit down.” A sailor ran up to their deck chairs and implored them to leave because “it was the last boat on the ship.”33 Isidor and Ida allegedly accompanied the two ladies to a boat on the port side, number 12, and Ida waited to wave goodbye to them as it was lowered.34

The flaws in Imanita Shelley’s account of Ida’s solicitousness are numerous, beginning with provable falsehoods, such as the fact that there were still nearly a dozen lifeboats left to launch from the Titanic when number 12 was lowered at about one thirty, which means no sailor was running up and down the Promenade proclaiming it “the last boat on the ship.” She lied, prolifically, about the sinking later, including glibly responding to a letter from the grieving relative of a lost passenger, “You ask if he wore a life-belt. Alas! no, they were too scarce.”35 It was an appallingly insensitive lie, considering that the Titanic in fact had thousands of life belts, far more than her capacity for passengers and crew. However, Mrs. Shelley pursued a publicity feud against the White Star Line in the weeks after the sinking, constantly returning to the apparent outrage that they had not upgraded her gratis from a cabin “that could only be called a cell,” an assessment she saw fit to stress even when called to testify at the Senate inquiry, which sought to understand how so many lives had been lost rather than investigate the woes of Imanita’s malfunctioning radiator.36 It is also doubtful that the Strauses, for whom there is no record of any previous friendship with Imanita Shelley or her family, could have heard that a passenger in Second Class was claiming to have tonsillitis and then, during the evacuation, known where to find her. Ida and her husband had spent about thirty minutes “mingling with the other passengers” near the Grand Staircase and first-class Promenade Deck after the initial call to the boats, without expressing any worry about, or knowledge of, Imanita Shelley.37 Keen to link her name to that of some of the Titanic’s most prestigious casualties, Imanita also dubiously claimed to have been the last person to see the journalist William Stead alive, “alone, at the edge of the deck, near the stern, in silence and what seemed to me a prayerful attitude, or one of profound meditation.”38

One of Tommy Andrews’s preoccupations was the need to start moving the third-class passengers up to the Boat Deck as quickly and as efficiently as possible.39 After stewards had passed over more blankets and Lifeboat 5 had left, Andrews went back inside to continue his mission to move passengers to the Boat Deck. As he had with Annie Robinson, he told Mary Sloan, still knocking on passengers’ doors, to put on her life belt “and go on deck.”40 Retracing Andrews’s movements with precision after this point in the sinking is unfortunately not always possible. However, given that he had gone through every corridor of accommodation in First Class before journeying to Scotland Road, where he allegedly urged stewards to shepherd third-class passengers “up on deck,” it seems unlikely that he did not also use Scotland Road to visit Second Class.

Unlike the aesthetic kaleidoscope in First Class, the Titanic’s Second Class was decorated with somber, wood-heavy similarity. All three of its main public rooms—its Smoking Room, Library, and Dining Saloon—were paneled in mahogany or “handsomely carried out in oak”—as was its staircase, up which its 284 passengers were ushered from their cabins and out onto the Boat Deck with relative ease.41 Of all the classes on the Titanic, it was Second that had the clearest path to the lifeboats—unlike First, with its numerous exits onto different parts of the Boat and Promenade spaces, and unlike Third, which was split into two sections, one in the bow and the other in the stern, and kept from easily accessible distance of the other two classes in order for the Titanic to conform with US quarantine laws.

Andrews’s instructions to the stewards concerning Third Class speak to one of the most distressing and horrible parts of the Titanic’s legend, in which those traveling in Third Class were deliberately locked below until the other passengers were safely in the lifeboats. Cited in support of this wretched scenario are testimonies from two survivors. The first, and most frequently referenced in passing if not in specifics, is from the twenty-one-year-old Anglo-Irish immigrant Daniel Buckley.42 When looked at in detail, Buckley’s statement to the American inquiry mentions only one locked gate, not inside Third Class but at the top of a short stairwell of about nine or ten steps, leading from a third-class promenade space to that of Second Class.43 He mistakenly, though understandably, assumed it led to First. This gate, low enough for a man to step over comfortably, was unlocked at the time of the collision, although a crew member, one of hundreds who did not realize the Titanic was sinking until it was too late, locked it when he saw dozens of passengers walking through in what he assumed was a contravention of the US immigration laws that the crew were under strict instructions to uphold. After he had bolted it, some passengers continued to clamber over it until one third-class gentleman decided that it being locked was discouraging the more conservative or nervous travelers from going up to the boats, at which point he kicked the lock open.44 This was the only incident of obstruction that Buckley recalled. To the question “Was there any effort made on the part of the officers or crew to hold the steerage passengers in the steerage?” Buckley answered, “I do not think so.”45 When asked, specifically, what he thought a third-class passenger’s chances of survival had been, Buckley told the querying Senator, “I think they had as much chance as the first and second class passengers.”46 Single men traveling on a third-class ticket were housed in cabins in the bow, separated by a long corridor from families and unmarried ladies, who were accommodated in the stern. It was thus in these cabins that the first passenger sightings of flooding occurred, and Buckley recalled that, as soon as that became clear, far from discouraging them from going to the lifeboats, stewards rushed through the single males’ corridors shouting, “Get up on deck, unless you want to get drowned!”47

The second eyewitness testimony to recall locked gates on the night of the sinking comes from Norwegian farmer Olaus Jørgensen Abelseth, who in a letter written to his father four days after the sinking made no mention of being trapped, but who later remembered that while on his way from cabin G-63 to find his unmarried sister, Karen, he encountered barriers between various corridors, which he had to ask the crew to open.48 These were the gates locked every night between the two sections of Third Class, used as a selling point to convince female travelers that they would be safe from harassment on White Star ships.

There is thus no account from any survivor mentioning iron grilles being bolted into place to keep the classes separate after Captain Smith gave the order to fill the lifeboats, much less of staff physically beating the passengers to keep them belowdecks. When pressed about unhelpful crew members, Daniel Buckley mentioned only one sailor, who became irate after he saw the promenade gate’s lock being kicked open.49 Furthermore, at no point during the hundreds of exploratory dives to the Titanic’s wreck conducted since its discovery in 1985 have the gates to and from Third Class been found in their locked position, whereas many have been photographed or filmed unlocked and open.

While there is no evidence whatsoever that crew members actively conspired to hold them below, and much to the contrary, Daniel Buckley was nonetheless profoundly incorrect when he told the Senator that those in Third Class “had as much chance as the first and second class passengers” of surviving. Basic mathematics disproves him when one considers that 62.5 percent of those in First Class were saved, against 41.2 percent in Second and 25.3 percent in Third. It should, for fairness’ sake, be pointed out that not all historians or statisticians would accept that these figures are as damning as they appear on first inspection, instead arguing that the defining contributory factor to surviving the Titanic disaster was gender rather than class—with 68 percent of female passengers saved, against 31.9 percent of the men, while 44 percent of those in First Class were women, compared to only 23 percent in Third.50 Gender was a major component in explaining the comparative loss of life in each of the Titanic’s three classes of accommodation. Nearly half of third-class women were saved, compared to only 16.2 percent of the men; yet 97.2 percent of first-class women lived, which leaves room for three further explanations for why Third Class suffered a higher casualty rate than the others.

The first is the crew’s ignorance of the situation. The recollections of Daniel Buckley and Olaus Jørgensen Abelseth refer to crew members, posted to the bloc of third-class cabins for single men, hurrying their passengers on deck. Those cabins were located close to the site of the ship’s impact with the iceberg, while the rest of Third Class, including its two public social spaces, the General Room and the Smoking Room, were positioned in the stern, the last point on the Titanic that night where it became obvious that something was physically wrong with the ship. To describe Captain Smith’s handling of this particular aspect of the sinking as a dereliction of duty seems charitable for, while he had found time to personally encourage the Countess of Rothes and Gladys Cherry to return to their stateroom and dress warmly for the impending drama, he had somehow failed to muster the crew to inform them that the ship, according to her designer, had around ninety minutes left to live. The Countess of Rothes again proves a useful point of reference, when one bears in mind that after she rang for her steward to help her find a life belt, he professed ignorant surprise that the call to the lifeboats had been issued. This steward’s attitude was replicated hundreds of times across the Titanic, with many of his colleagues hearing garbled accounts of what had gone wrong and only realizing around the same time as their passengers that the ship was genuinely in danger. In light of their failure to be furnished with the facts, some sailors panicked at the sight of third-class passengers coming up to, or over, the small dividing gate between the stern and the second-class promenade. They also failed to nurture any sense of urgency among the families or unmarried women who congregated in the General Room, awaiting instructions and not noticing a marked tilt in the deck until the last forty-five minutes or hour of the sinking.

Secondly, unlike First and Second Class, most third-class passengers did not have English as their first language. About nine out of every ten first-class passengers and eight out of ten in Second Class were native English-speakers, while the same was true of only two-fifths in Third.51 The overwhelming majority of the Titanic’s crew, and all of its internal signs, had English as their only language. Third Class’s labyrinthine corridors frustrated the evacuation even more when crew struggled to impart directions to the German, Magyar, Arabic, French, Dutch, Bulgarian, Chinese, Danish, Finnish, Greek, Italian, Norwegian, Portuguese, Russian, Swedish, and Turkish speakers in Third Class. The Countess of Rothes had noticed how “terrified” and confused the Peñascos were while waiting to board the lifeboats; she was able to offer help and information to them only thanks to their having French as a shared language. María-Josefa de Peñasco’s paralyzed bewilderment played out in hundreds of third-class passengers, without the fortuitous coincidence of standing next to someone who could communicate properly with them.

Finally, there were the problems posed by the geography of Third Class. No one can reasonably fault the White Star Line for designing the respective classes of accommodation to conform with the laws put in place by the US government concerning immigration. The alternative to compliance was to eradicate Third Class as an option on board their ships. However, that is not to say that there were not grave errors in other decisions regarding its design. While Third Class could not be granted access in ordinary circumstances to the adjoining promenades provided for First and Second Class, there was no reason not to install a set of davits on the Poop Deck, to which they did have easy and frequent access as their designated on-deck space. That this was a wretched mistake was evidenced by subsequent alterations made to the Titanic’s younger sister, the Britannic, which had davits positioned on her third-class outdoor decks. The failure to envisage any collision damaging enough to require the evacuation of everyone on board in a relatively short period of time meant that third-class passengers, speaking over a dozen languages between them, needed to be guided to a part of the ship of which they had no prior experience since it was constructed to discourage their interaction with it, by crew members who struggled both to communicate with them and fully to appreciate the danger until it was too late. It was thus egregious if commonplace incompetence in design and command, rather than malevolent snobbery, that helps explain the heavier loss of life among third-class passengers. Without lessening its tragedy, it at least serves to make the final figures less gut-wrenchingly, intentionally monstrous.

A rumor later circulated that the Thayer men had attempted to use their position as first-class ticket holders to board the lifeboats ahead of other passengers. However, it seems that during the early stages of the evacuation, they, along with most passengers, assumed that there were sufficient lifeboat spaces for everyone on board and that their questions to the crew were to establish which of the lifeboats on the Boat Deck had been set aside to evacuate passengers from different parts of the ship. Each crew member they asked seemed to be sufficiently unsure to send them to inquire from another officer at a different lifeboat.52 An unpleasant appreciation that there was no such organization at play began to dawn when Thayer, his son, and Milton Long, having briefly returned to the warmth of the Grand Staircase, were approached by one of the stewards, who had waited on their table in the Dining Saloon since Wednesday, and gave them the unwelcome news that Marian was still on the Titanic.53 They found her on the port side, in a towering bad temper, still accompanied by Margaret Fleming, her maid, Elizabeth Eustis, and Martha Stephenson. In the course of the previous fifteen or twenty minutes, they had been moved between the Boat and Promenade decks as orders arose in contradiction of one another about their lifeboat’s point of loading. Marian had snapped at one of the crew, “Tell us where to go and we will follow you. You ordered us up here and now you are taking us back.”54 Thayer decided to stay with them until he could see all the ladies safely into a boat, so he escorted the party indoors, cutting through a Lounge still “filled with a milling crowd” to reach some of the forward port-side boats.55 In that milieu, their group became separated and, theorizing that Jack had a companion in Milton, Thayer pressed ahead with the four women. His failure to go back immediately to locate his son need not be judged an act of paternal neglect since, by all accounts, the two Thayers shared a close and loving relationship. Rather, by the time Thayer and the four women rushed through the Lounge the situation on the Titanic had deteriorated significantly.

Most passengers had a moment in which complacency was replaced by concern or justified fear. For Marian Thayer, it had been as “rockets were going up beside us, and the Morse signal light had begun” and she turned to see stokers standing next to her, bedraggled and some soaked in their sleeveless white work shirts, then third-class passengers coming up onto the first-class decks, carrying their uninsured luggage with which they hoped to start their new lives in the United States. No suitcases were permitted in any of the Titanic’s lifeboats, leading to anguished scenes of begging, “struggling and fighting, deliriously” between the officers and some of the third-class passengers. A few second-class passengers were overheard laughing at the sight of the suitcases, until another second-class traveler told them to shut up.56

Elsewhere, there were signs of collective unraveling. The band had quit the Lounge and relocated to one of the entrance halls between the Boat Deck and the Grand Staircase.57 Although the ship’s secondary post-collision list, to starboard, had gently been righted when Boiler Room 5 flooded to capacity, the Titanic had since, in addition to the gradually more perceptible dip forward, taken on a noticeable list to port due to the renewed unevenness of the belowdecks deluge. In the thirty or so minutes since the Countess of Rothes’s lifeboat had left, eight more had departed at closer intervals than that between hers and Dorothy Gibson’s.58 Fifth Officer Lowe had fired shots into the air to discourage pushing at Lifeboat 14, pleading with a male passenger who climbed in to “get out and be a man—we have women and children to save.”59 When that did not work, Lowe turned to the crowd and shouted, “Stand back! I say, stand back! The next man who puts his foot in this boat, I will shoot him down like a dog.” A second-class passenger, helping his wife and sobbing seven-year-old daughter over the gap between the deck and the boat, assured Lowe, “I’m not going in, but for God’s sake look after my wife and child.”60 When it was finally lowered, number 14 caught in its ropes, which had to be cut to allow it to drop the final five or six feet into the water.61 Thayer, who helped some passengers into the neighboring Lifeboat 10, almost certainly saw these scenes, and they may explain why he decided to move his wife, her maid, and their friends through the Lounge to the forward-positioned boats. During the boarding of number 10, they saw a woman fall through the gap between the deck and the lifeboat. She was caught, mercifully, by an eagle-eyed passenger on the Promenade Deck below, who dragged her on board and escorted her back to the Boat Deck, where she successfully made it to the safety of the lifeboat.62 Worse screams were heard from further below when Lifeboat 13 was hit by water pouring out from one of the Titanic’s condenser exhausts and pushed into the path of the descending Lifeboat 15, which nearly crushed everyone in 13, before the latter’s occupants managed to shove their craft away from the Titanic’s hull with their oars.

Based on the accounts of eyewitnesses, this sketch depicts the moment when Lifeboat 13 was nearly crushed by the lowering of number 15.

Thayer’s decision to relocate his party paid dividends when they were directed down, once again, to the Promenade Deck, where Second Officer Lightoller successfully had some of the windows pried away. There was another brief delay on account of the Titanic’s deepening list to port, which had opened up a gap between the deck and the boats. “Ladders were called for,” according to Marian, “but there being none, it was necessary to lash two steamer chairs to serve as a sort of gang plank to enable the women to get into the boat.” Marian’s maid, Elizabeth, and Martha were helped over this improvised walkway, held together by rope and faith, before Thayer told Marian he would go back to look for their son and gave her his arm as she stumbled into the boat. Several of the Thayers’ acquaintances had gathered to help the crew with the lifeboats, including Marian’s new friend, Major Archibald Butt, and his companion Frank Millet. The Ryersons, the Thayers’ friends who had lost their son to a car crash earlier that week, were among those boarding Lifeboat 4. Mrs. Ryerson prepared to follow Marian, with her thirteen-year-old son, also called Jack, attempting to join her until Second Officer Lightoller put out his arm and declared, “That boy can’t go.” Arthur Ryerson, on deck with Thayer, stepped forward and said, “Of course, that boy goes with his mother; he’s only thirteen.” Lightoller backed down and Jack Ryerson was passed to a sailor in the boat, joining his two sisters, his mother’s lady’s maid, and his governess. If Emily Ryerson had been asked to leave her only surviving son on the Titanic, she almost certainly would have refused. Instead, as she recalled later, “I turned and kissed my husband, as we left he and the other men I knew—Mr. Thayer, Mr. Widener, and others—were all standing there together very quietly.” They were soon joined by two colonels, Gracie and Astor, the latter of whom had changed his mind about the dangers posed by the lifeboats. He passed his pregnant wife to Gracie, who helped her into Marian Thayer’s lifeboat, while Astor spoke quietly to Lightoller, asking if he could accompany Madeleine in light of her condition. According to Gracie, Lightoller replied, “No, sir, no men are allowed in these boats until the women are loaded first.” Astor “did not demur, but bore the refusal bravely and resignedly, simply asking the number of the boat to help find his wife later in case he also was rescued.” Kornelia Andrews, an occupant in one of the lifeboats Thayer assisted with, was deeply and patriotically moved by the sight of

that unbroken line of splendid Americans, not allowed to get into the boats before the women and children were off. It would make you proud of your countrymen. There was Mr. Thayer, [vice] president of the Pennsylvania Railroad; Col. Astor waving a farewell to his beautiful young wife; Major Archibald Butt, Taft’s first aide; Mr. Case, president of the Vacuum Oil Co., all multi-millionaires, and hundreds of other men, standing without complaint or murmur, not making one attempt to save themselves, but happy to think wives and relatives were in the boat. Was that not chivalry for you?

Astor lingered with the other husbands for a few moments, until the lifeboat was lowered, and then he walked away. There are no firmly corroborated sightings of him after that.63

The continuing evacuation, with the shouting of the frightened and the commands of the officers, was now illuminated only by the ship’s electric lights, still burning thanks to the engineers from Ireland and England who had chosen to stay below to keep the power running as long as possible. The last distress rocket was fired around the time Marian Thayer left the Titanic. Thayer stayed on the Promenade with George Widener, Colonel Gracie’s friend James Smith, and, for a brief time until they wandered off, Astor, Butt, Millet, and Gracie. Realizing that nearly all the lifeboats had gone and that in any case there were not enough for everyone still left on board, Gracie wrote that their group “experienced a feeling which others may recall when holding the breath in the face of some frightful emergency and when ‘vox faucibus haesit,’ as frequently happened to the old Trojan hero of our school days.”I64

Looking at the Titanic from her place in the lifeboat where she had been for forty-five or fifty minutes, Lady Rothes kept her word to look after María-Josefa de Peñasco, “trying to soothe her & keep her spirits up by saying I was sure her husband would follow in the next boat, tho’ I knew by this time there was no chance of that & very little hope for anyone.”65

I. From Virgil’s Aeneid, referring to the moment when Aeneas’s voice catches in his throat.