The astonishing percentage of the genome that didn’t code for proteins was a shock. But it was the scale of the phenomenon that was surprising, not the phenomenon itself. Scientists had known for many years that there were stretches of DNA that didn’t code for proteins. In fact, this was one of the first big surprises after the structure of DNA itself was revealed. But hardly anyone anticipated how important these regions would prove to be, nor that they would provide the explanation for certain genetic diseases.

At this point it’s worth looking in a little more detail at the building blocks of our genome. DNA is an alphabet, and a very simple one at that. It is formed of just four letters – A, C, G and T. These are also known as bases. But because our cells contain so much DNA, this simple alphabet carries an incredible amount of information. Humans inherit 3 billion of the bases that make up our genetic code from our mother, and a similar set from our father. Imagine DNA as a ladder, with each base representing a rung, and each rung being 25cm from the next. The ladder would stretch 75 million kilometres, roughly from earth to Mars (depending on the relative positions of their orbits on the day the ladder was put in place).

To think of it another way, the complete works of Shakespeare are reported to contain 3,695,990 letters.1 This means we inherit the equivalent of just over 811 books the length of the Bard’s canon from mum and the same number from dad. That’s a lot of information.

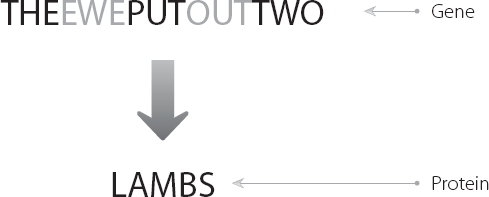

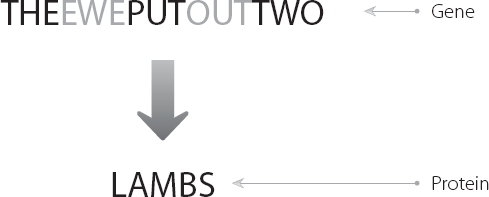

If we extend our alphabet analogy a bit further, the DNA alphabet encodes words of just three letters each. Each three-letter word acts as the placeholder for a specific amino acid, the building blocks of proteins. A gene can be thought of as a sentence of three-letter words, which acts as the code for a sequence of amino acids forming a protein. This is summarised in Figure 2.1.

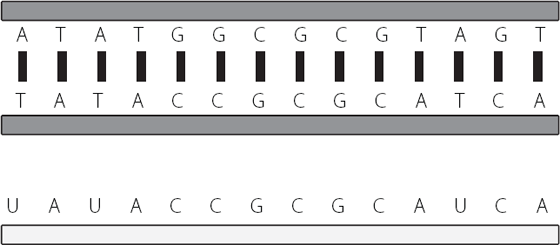

Each cell usually contains two copies of any given gene. One was inherited from the mother and one from the father. But although there are only two copies of each gene in a cell, that same cell can create thousands and thousands of the protein molecules encoded by a specific gene.

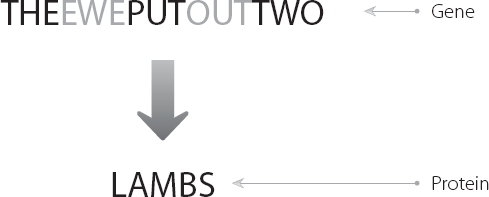

This is because there are two amplification mechanisms built into gene expression. The sequence of bases in the DNA doesn’t act as the direct template for the protein. Instead, the cell makes copies of the gene. These copies are very similar to the DNA gene itself, but not identical. They have a slightly different chemical composition and are known as RNA (ribonucleic acid, instead of the deoxyribonucleic acid in DNA). Another difference is that in RNA, the base T is replaced by the base U. DNA is formed of two strands joined together via pairs of bases. We could visualise this as looking a little like a railway track. The two rails are held together by a base on one rail linking to a base on the other, as if the bases were holding hands. They only link up in a set pattern. T holds hands with A, C holds hands with G. Because of this arrangement, we tend to refer to DNA in terms of base pairs. RNA is a single-stranded molecule, just one rail. The key differences between DNA and RNA are shown in Figure 2.2. A cell can make thousands of RNA copies of a DNA gene really quickly, and this is the first amplification step in gene expression.

Figure 2.1 The relationship between a gene and a protein. Each three-letter sequence in the gene codes for one building block in the protein.

The RNA copies of a gene are transported away from the DNA to a different part of the cell, called the cytoplasm. In this distinct region of the cell, the RNA molecules act as the placeholders for the amino acids that form a protein. Each RNA molecule can act as a template multiple times, and this introduces the second amplification step in gene expression. This is shown diagrammatically in Figure 2.3.

We can visualise this using the analogy of the knitting pattern from Chapter 1. The DNA gene is the original knitting pattern. This pattern can be photocopied multiple times, akin to producing the RNA. The copies can be sent to lots of people who can each knit the same pattern multiple times, just like creating the protein. It’s a simple but efficient operating model and it works – one original pattern resulted in lots of soldiers with warm feet in the Second World War.

Figure 2.2 The upper panel represents DNA, which is double-stranded. The bases – A, C, G and T – hold the two strands together by pairing up. A always pairs with T, and C always pairs with G. The lower panel represents RNA, which is single-stranded. The backbone of the strand has a slightly different composition from DNA, as indicated by the different shading. In RNA, the base T is replaced by the base U.

Figure 2.3 A single copy of a DNA gene in the nucleus is used as the template to create multiple copies of a messenger RNA molecule. These multiple RNA molecules are exported out of the nucleus. Each can then act as the instructions for production of a protein. Multiple copies of the same protein can be produced from each messenger RNA molecule. There are therefore two amplification steps in generating protein from a DNA code. For simplicity, only one copy of the gene is shown, although usually there will be two – one inherited from each parent.

The RNA molecule acts as a messenger molecule, carrying a gene sequence from the DNA to the protein assembly factory. Rather logically it is therefore known as messenger RNA.

Taking out the nonsense

So far, things might seem very straightforward but scientists discovered quite some time ago that there is a strange complication. Most genes are split up into bits that code for the amino acids in a protein and intervening bits that don’t. The bits that don’t are like gobbledegook in the middle of a string of sensible words. These intervening bits of nonsense are known as introns.

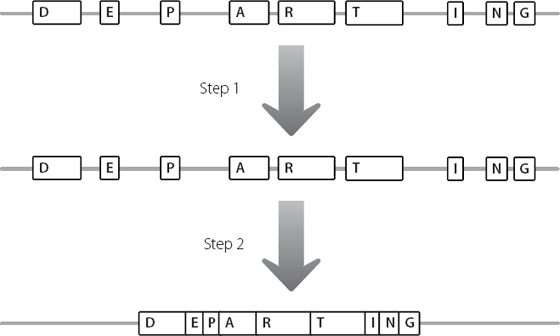

When the cell makes RNA, it originally copies all of the DNA letters in a gene, including the bits that don’t code for amino acids. But then the cell removes all the bits that don’t code for protein, so that the final messenger RNA is a good instruction set for the final protein. This process is known as splicing, and Figure 2.4 shows diagrammatically how this happens.

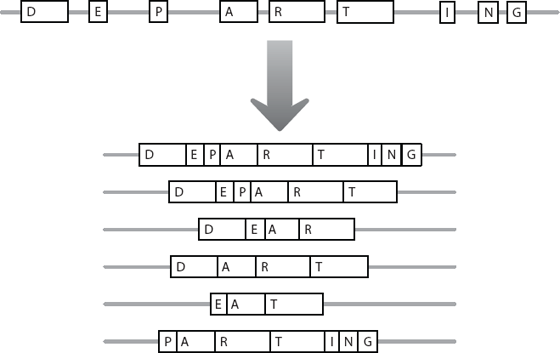

As Figure 2.4 shows, a protein is encoded from modular blocks of information. This modularity gives the cell a lot of flexibility in how it processes the RNA. It can vary the modules which it joins together from a messenger RNA molecule, creating a range of final messengers that code for related but non-identical proteins. This is shown in Figure 2.5.

The bits of gobbledegook between the parts of a gene that code for amino acids were originally considered to be nothing but nonsense or rubbish. They were referred to as junk or garbage DNA, and pretty much dismissed as irrelevant. As mentioned earlier, from here on in, we’ll use the term ‘junk’ to denote any DNA that doesn’t code for protein.

Figure 2.4 In step 1, DNA is copied into RNA. In step 2, the RNA is processed so that only the amino acid-coding regions, denoted by boxes containing letters, are joined together. The intervening junk regions are removed from the mature messenger RNA molecule.

Figure 2.5 An RNA molecule can be processed in different ways. As a result, different amino acid-coding regions can be joined together. This allows different versions of a protein molecule to be produced from one original DNA gene.

But we now know that they can have a very big impact. In Friedreich’s ataxia, which we met in Chapter 1, the disorder is caused by an abnormally expanded stretch of GAA repeats in one of the junk regions, between two sections that encode amino acids. This raised the perfectly reasonable question – if the mutation doesn’t affect the amino acid sequence, why do people with this mutation develop such debilitating symptoms?

The mutation in the Friedreich’s ataxia gene occurs in the junk region between the first two amino acid-coding regions. In Figure 2.5, this would be between regions ‘D’ and ‘E’. A normal gene contains from five to 30 GAA repeats but a mutated gene contains from 70 up to 1,000 repeated GAA motifs.2 Researchers showed that when cells contained this expanded repeat, they stopped producing the messenger RNA encoded by the gene. Because they didn’t make messenger RNA, they couldn’t make the protein either. If you don’t send out the copies of the knitting patterns, the soldiers don’t get socks.

In fact, the cells didn’t even make the long, unprocessed RNA copy of the gene.3 The big GAA expansion acts as a ‘sticky’ region, which prevents good copying of the DNA. It’s analogous to trying to photocopy a 50-page document, when pages four to twelve have been glued together. They won’t feed into the copier, and the process grinds to a halt, for that particular document. In the case of the Friedreich’s ataxia gene, no copying means no RNA, which means no protein.

It’s not completely clear why lack of the protein encoded by the Friedreich’s ataxia gene causes the disease symptoms. The protein seems to be involved in preventing iron overload in the parts of the cell that generate energy.4 When a cell fails to produce the protein, the iron rises to toxic levels. Some cell types seem to be more sensitive than others to iron levels, and these include the ones affected in the disease.

A related but different mechanism accounts for Fragile X syndrome, the form of learning disability we encountered in Chapter 1. The mutation in Fragile X syndrome is the expansion of a CCG three-base repeat. Similarly to the Friedreich’s ataxia mutation, there are usually fifteen to 65 copies of the repeat on a normal chromosome. On a chromosome carrying the Fragile X mutation there are from around 200 to several thousand copies.5,6 But the expansion lies in a different part of the gene in Fragile X compared with Friedreich’s ataxia. The mutation is found before the first amino acid-coding region, essentially in the junk to the left of block ‘D’ in Figure 2.5. When the junk repeat gets very large, no messenger RNA is produced, and consequently there is no protein produced from this gene.7

The function of the Fragile X protein is to carry lots of different RNA molecules around in the cell. This gets them to the correct locations, influences how these RNAs are processed and how they generate proteins. If there is no Fragile X protein, the other RNA molecules aren’t properly regulated, and this plays havoc with the normal functioning of the cell.8 For reasons that aren’t clear, the neurons in the brain seem particularly sensitive to this effect, hence the learning disability in this disorder.

An everyday analogy may help with visualising this. In the UK, a relatively small amount of snow can incapacitate the transport networks. The snow covers the roads and the railway tracks, preventing cars and trains from moving. When this happens, people can’t get to their place of work and this creates all sorts of problems. Schools can’t open, deliveries aren’t made, banks can’t dispense cash, etc. One starting event – the snow – has all sorts of consequences because it ruins the transport systems in society. A similar thing happens in Fragile X syndrome. Just like snow on the roads and railway tracks, the effect of the mutation is to mess up a transport system in the cell, with multiple knock-on effects.

Switching off the expression of a specific gene is the key step in the pathology of both Friedreich’s ataxia and Fragile X syndrome. Support for this hypothesis has been provided by very rare cases of both disorders. There are small numbers of patients where the repeat in the junk regions is of the same small size found in most healthy people. In these patients, there are mutations that change the sequence in the amino acid-coding regions. These particular amino acid sequence changes actually make it impossible for the cell to produce the protein. In other words, it doesn’t matter why the protein isn’t expressed. If it’s not expressed, the patients have the symptoms.

Just when you have a nice theory

So far it might seem like there’s a nice straightforward theme emerging. We could speculate that expansions in the junk regions are only important because they create abnormal DNA. This DNA isn’t handled properly by the cells, resulting in a lack of specific important proteins. We could suggest that normally these junk regions are unimportant, with no significant role in the cell.

But there is something that argues against this. The normal range of repeats in both the Fragile X and Friedreich’s ataxia genes is found in all human populations, and has been retained throughout human evolution. If these regions were completely nonsensical we would expect them to have changed randomly over time, but they haven’t. This suggests that the normal repeats have some function.

But the real grit in this genetic oyster comes from myotonic dystrophy, the disorder that opened Chapter 1. The myotonic dystrophy expansion gets bigger as it passes down the generations. A parent’s chromosome may contain the sequence CTG repeated 100 times, one after another. But when they pass this on to their child, this may have expanded so the child’s chromosome has the sequence CTG repeated 500 times. As the number of CTG repeats gets larger, the disease becomes more and more severe. This isn’t what we would expect if the expansion just switches off the nearby gene. All cells of someone with myotonic dystrophy contain two copies of the gene. One carries the normal number of repeats, and the other carries the expanded number. So, one copy of the gene should always be producing the normal amount of protein. That would mean that the most the overall levels of the protein should drop would be about 50 per cent.

We could hypothesise that as the repeat gets longer there is progressively less gene expression from the mutant version of the gene. This could lead to a gradual decline in the amount of protein produced overall. This could range from a 1 per cent drop overall for fairly small expansions, to a 50 per cent final decrease for the large ones. This could lead to different symptoms. The problem is that there aren’t really any inherited genetic diseases like this. We just don’t see disorders where very minor variations in expression have such a big effect (all patients with the expansion develop symptoms), but with such fine tuning between patients (the symptoms becoming more extreme as the expansion lengthens).

It’s worth looking at where the expansion occurs in the myotonic dystrophy gene. It’s right at the far end, after the last amino acid-coding region. In Figure 2.5, this would be on the horizontal line to the right of box ‘G’. This means that the entire amino acid-coding region can be copied into RNA before the copying machinery encounters the expansion.

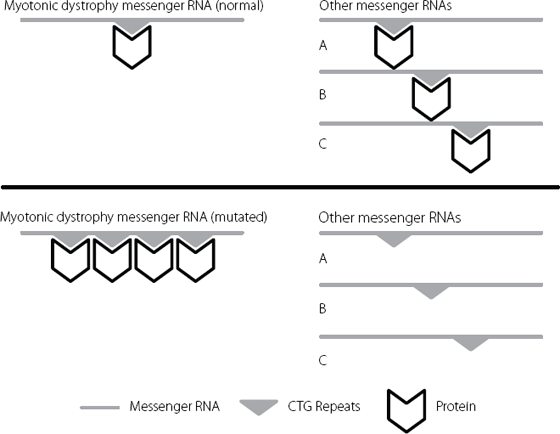

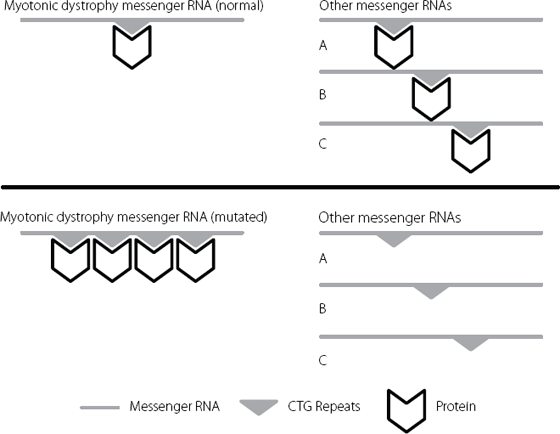

It’s now clear that the expansion itself gets copied into RNA. It is even retained when the long RNA is processed to form the messenger RNA. The myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA does something unusual. It binds lots of protein molecules that are present in the cell. The bigger the expansion, the more protein molecules that get bound. The mutant myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA acts like a kind of sponge, mopping up more and more of these proteins. The proteins that bind to the expansion in the myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA are normally involved in regulating lots of other messenger RNA molecules. They influence how well messenger RNA molecules are transported in the cell, how long the messenger RNA molecules survive in the cell and how efficiently they encode proteins. But if all these regulators are mopped up by the expansion in the myotonic dystrophy gene messenger RNA, they aren’t available to do their normal job.9 This is shown in Figure 2.6.

Again an analogy may help. Imagine a city where every member of the police force is engaged in controlling a riot in a single location. There will be no officers left for normal policing, and burglars and car thieves may run amok elsewhere in the city. It’s the same principle in the cells of people with the myotonic dystrophy mutation. The CTG repeat sequence expansion in a single gene – the myotonic dystrophy gene – ultimately leads to mis-regulation of a whole number of other genes in the cell.

Figure 2.6 The upper panel shows the normal situation. Specific proteins, represented by the chevron, bind to the CTG repeat region on the myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA. There are plenty of these protein molecules available to bind to other messenger RNAs to regulate them. In the lower panel, the CTG sequence is repeated many times on the mutated myotonic dystrophy messenger RNA. This mops up the specific proteins, and there aren’t enough left to regulate other messenger RNAs. For clarity, only a small number of repeats have been represented. In severely affected patients, they may number in the thousands.

This is because the expansion mops up more and more of the binding proteins as it gets larger. This leads to disruption of a greater quantity of other messenger RNAs, causing problems for increasing numbers of cellular functions. This eventually results in the wide range of symptoms found in patients carrying the myotonic dystrophy mutation, and explains why the patients with the largest repeats have the most severe clinical problems.

Just as we saw in Friedreich’s ataxia and Fragile X syndrome, the normal CTG repeat sequences in the myotonic dystrophy gene have been highly conserved in human evolution. This is consistent with them having a healthy and important functional role. We are even more convinced this is the case for the myotonic dystrophy gene because of the proteins that bind to the repeat in the messenger RNA. These also bind to shorter repeat lengths, of the size that are present in normal genes. They just don’t bind in the same abundance as they do when the repeat has expanded.

It’s clear from the myotonic dystrophy example that there is a reason why messenger RNA molecules contain regions that don’t code for proteins. These regions are critical for regulating how the messenger RNAs are used by the cells, and create yet another level of control, fine-tuning the amount of protein ultimately produced from a DNA gene template. But what no one appreciated when the myotonic dystrophy mutation was identified, almost ten years before the release of the human genome sequence, was just how extraordinarily complex and variable this fine-tuning would turn out to be.