Various tales told of the hero are composed of recurrent motifs, contrasting the self and its reflected image. The role of the entheogen is essential in bringing the two personae into an alliance. This reconciliation is the fundamental objective of psychotherapy. Myth provides a pathway for self-discovery.

Weird folk who materialize from the entheogen and act as guides are not the strangest creatures you encounter on a trip. The strangest encounter is with yourself. The mirror casts back a beguiling likeness where everything is reversed. Narcissus was so entranced with his reflected image that he fell into a ‘narcosis’, which is a word derived from the psychoactive narkissos flower. He never returned, but plunged down through the watery reflection into the world beyond. Some claimed that it was actually his sister he saw, a twin—his opposite.

Myth provides a pathway for self-discovery.

Lewis Carroll’s sequel to Alice in Wonderland, Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There, popularized a divining technique of the 19th Century elite. Advances in the manufacture of mirrors had made it possible to produce full wall-sized mirrors. Such a mirror could be installed behind a blank door. Guests, suitably medicated with opiate tinctures, could hallucinate upon their own assembled party reflected in the opened doorframe.

In the paradigmatic myth of the hero, this reflected image or alternate persona represents all the attributes rejected in the defining of the self, a being composed of all the opposite dichotomous characteristics that define one’s dominant identity. It is the essential polarity in order for one to be who one is, for without it, one cannot be: the male, who is not female; the adult, who is not the child; the human, who is not the beast; the living, who is not the dead. As the opposite, it is the ultimate enemy, the far point of the journey. It is not simply the enemy, however, since it is one’s other half. It is also the ultimate beloved. As the other half of the self, it lurks forever on the fringes of perception, yearning to reengage in an agonistic embrace that is both battle and love.

This other person is a mythological theme worldwide. The Germans called it the Doppelgänger or ‘double walker.’ The Norse and the Finnish peoples thought it walked in front of one as a view into the future. It is commonly seen as a harbinger of misfortune and has overtones of clairvoyant altered perception, a glimpse of oneself caught in peripheral vision. It is probably derived from the shamanic access to the experience of bilocation, the ability to be simultaneously somewhere else, or distant vision, seeing things somewhere else.

Everyone carries a Shadow, and the less it is embodied in the individual’s conscious life, the blacker and denser it is. If it is repressed and isolated from consciousness, it is liable to burst forth suddenly in a moment of unawareness.

—C.G. Jung

Psychology and Religion

In psychotherapy, this unrecognized and rejected other may encroach upon the self and enact its hostility by manifesting itself as various psychoses. A cure is accomplished by a journey into the forgotten past, whose contents have been repressed into the subconscious. There one must confront oneself.

The original state of spiritual confusion experienced by the seekers leads in modern therapy to an analysis and interpretation of irrational thoughts expressed in dreams and fantasies (anamnesis). The acceptance of this material from the unconscious widens the perspective and awareness of the conscious mind, and enables the enriched personality to better cope with its environment.

—C.G. Jung

The Personification of the Opposites

A battle ensues of heroic dimension. The outcome cannot be surrender by either side, since that would result in only half a person. The confrontation must end in reconciliation, so that the rejected self plays a proper recessive role in a bipolar stability expressing total integration. Such a person is an adult at peace with the child within, no longer subject to infantile fits of tantrum, or a male who can mediate with his own traits of femininity.

An effective guide for this journey, which can be experienced either in psychoanalysis or in rites of initiation, is another of these strange creatures one encounters on a trip, the half-person or unilateral figure, a worldwide metaphor for the entheogen. It is also the face reflected in the mirror.

The Greek version of this unilateral creature is described in Plato’s Symposium. The comedic playwright Aristophanes offers the myth of the half-person or one-sided creature as his contribution to the discussion of love at the drinking party. Originally, there were three sexes, male, female, and the hermaphrodite. These beings were total and perfect, spherical, with two faces in opposite directions, two sets of genitals, and eight limbs on which they could roll about with ease. The gods were jealous of their strength and spherical perfection, and they cut each in half to make them only half as strong. Then they turned each half’s face and four remaining limbs inward, drawing the perimeter of the severed skin together with a drawstring like a purse at what is now called the navel. Forever after, they would have to see the scar left from their severance and seek to repair the separation by embracing their other half.

Narratives featuring the half-man are found all over the globe…. It did not arrive at its vast distribution by way of diffusion… but it gives every indication of being a spontaneous expression of the imaginative unconscious.

—Rodney Needham

Circumstantial Deliveries

Hermaphroditic deity of creation

The poor creatures were doing this, but they were dying off, withering away, since their genitals were still on their backsides. The gods took pity on them and also moved the sex organs to the inner side. Thus the male could embrace his male counterpart, and the female her female other half. These were gay men and Lesbian women, but they might also under duress couple with the opposite sex and reproduce heterosexually, allowing the race of humans to continue in existence. The severed hermaphrodite, however, had a physical linkage with its other half in the corresponding sex organs of its opposite. Sex was really great for them. These half-hermaphrodites became creatures with an inordinate sexual drive: wanton women and profligate men, hypersexuality, as the psychologists label it, which is termed nymphomania in women and satyriasis in men.

Half-hermaphrodites became creatures with an inordinate sexual drive—wanton women and profligate men—hypersexuality which psychologists call nymphomania in women and satyriasis in men.

Plato put this speech in the mouth of the great comedian of the Dionysian theater. It is meant to be hilarious and outrageous. It is also, however, meant to encode something very true in the total context of the argument of the Symposium, which is the pathway to transcendent knowledge or revelation as the greatest of all loves. In Platonic philosophy, this is termed anamnesis, recognition and remembrance of one’s former existence in the empyrean, one’s truest other half.

The myth of the hermaphrodite is the tale of the origin of humankind, and it is a version of the Greek myth that humans were created out of mushrooms. The original spheres cut in half, with the skin drawn to the navel, radiating out with wrinkles, is a perfect likeness of the gill structures on the underside of the mushroom’s cap, suitably anthropomorphized by the addition of a head, arms, and legs. If these new mushroom people did not behave themselves, the gods threatened to slice them in half again, leaving them with only a single leg on which to hop up and down, as mushroom one-foots.

A similar myth describes the twin sons of Zeus known as the Dioscuri, who were born from a single egg. They are so similar, although dissimilar, that one is mortal and the other immortal, but they have vowed to share each other’s fate on alternating days. They, too, are anthropomorphized mushrooms, characterized by their mushroom caps and mushroom shields, which are the remnants of their split eggshell, and by a horizontal beam or pillar that connects the two.

The mushroom grows from an egg shape that separates into a lower and upper half by the thrust of the extending stipe, so that it comes to resemble a dumbbell. The navel of the radiating gills becomes the interconnection of the upper and lower halves, as the expanding cap, that at first appeared phallic, turns into the receptive vulva, and it appears now to copulate with itself as a hermaphrodite. This dumbbell plant was also known as the magical Promethean herb, a plant that grew with a double stem, half up, half down, to the hemispherical remnants of the split eggshell. No other plant can boast a double stem.

The original role for drugs like LSD when it was offered to the market was its potential use in facilitating psychoanalytic analysis and in allaying the anxiety of patients suffering from a terminal illness. Classical mythology lay at the onset of the new science of psychoanalysis in the 19th Century since it seemed to encode some of the most basic paradigms of human existence as experienced in the Western world. However, because of the condemnatory reaction of professional Classicists to the Psychedelic Revolution, its rich compendium of significant tales was placed largely off limits for people trying to comprehend the meaning of their visionary experiences, and they were forced, as we have said, to seek out more exotic myths and religions.

Rodney Needham draws attention to the wide dissemination of the ‘Unilateral Figures’ that are scattered around the world, from the Eskimos of the extreme North to the Yamaha of Tierra del Fuego, from the Nahua of Mexico to the folklore of Greece and Romania. If in the cultures where Needham finds ‘unilateral figures’ there was knowledge of the entheogens, here then will be proof that this ancient religion has existed even more widely than I thought.

—R. Gordon Wasson,

Persephone’s Quest

This was unfortunate because not only are the Classical paradigms among the most perfected and best documented exemplars and, in addition, indigenous to the Western tradition, but they also evolved from ancient shamanic rites with psychoactive sacraments that were still practiced in the religions of the Classical and Hellenistic Greco-Roman periods, including Christianity. The Greek hero and heroine tales are potentially as significant to the psychic traveler as they were to the scientists who used them to map the human psyche. They also, as we shall see, are equally applicable for initiatory preparation for the terminal journey.

There is only one story, although the actors involved have many faces. In what follows, we will establish the themes that never change, the story that is the only story ever told, what Joseph Campbell termed the ‘monomyth.’ Its therapeutic value is there for anyone willing to confront the image reflected in the mirror or to journey like Alice into the rabbit hole. We add to it the central theme of the entheogen, which burst onto the scene after Campbell’s formulation of the pattern. We also make more explicit what Freud and Jung, as scientists, were reluctant to confess publicly. What we reveal was also known to the great Sir George Frazer, author of The Golden Bough and Jane Ellen Harrison, of Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, but except for tantalizing bits, students will seek in vain for them to mention openly anything so lowly as the fairies’ mushroom.

There is only one story, although the actors involved have many faces.

The best example of the paradigm from Classical mythology is the story of the hero Perseus. He was the first of the many heroes who followed and he performed only one essential task, and hence he is the easiest to understand. He harvested the Medusa’s head. He picked the sacred mushroom. All the heroes that came after him, however, are variations upon the same mythic pattern. The shamanic motif of an entheogen is central to all these tales, but has gone largely ignored.

As with all the heroes, Perseus is ‘liminal,’ which is to say, he stands on the threshold or limen of a doorway that opens into different worlds on either side. In each he has an identity that mirrors the other, so that actually there are two heroes, one in either world, who would meet each other from opposite sides as they approach the doorway like a mirror. Since Classical Greek mythology evolved as reconciliation between an indigenous Anatolian-Mediterranean religious tradition where a goddess was supreme and an imported colonizing tradition occasioned by the immigration of a male dominant Nordic Indo-European culture with a supreme god, the hero has two possible roles to play. He can be either the subservient male of the former goddess or the male who dominates her in the service of the new presiding god.

The shamanic motif of an entheogen is central to all these tales, but has gone largely ignored.

It should be pointed out, however, that the cult of the mushroom was a shamanic tradition already established both among the Mesopotamian, Anatolian, Minoan Mediterranean, Egyptian, and Semitic peoples, and among the northern so-called Hyperborean immigrants. The ubiquity of the mushroom cults cannot be explained by physical contact between different cultures. It is most easily seen as the result of shamanic communion with the plant itself, reinforced by notions common to humanity, what Jung called the archetypes and Plato termed the remembrances and re-cognitions—anamnesis—from the empyrean.

The dual potential of the gateway is personified in the Roman god Janus, with a face in either direction. His epithet was ‘two-face’—bifrons. Sometimes, like the hermaphrodite, his other face is female. He lends his name to the month of January, looking back at the year past and forward to the coming year. The janitor is named after him, not as the person who cleans the building, but as the one who controls passage through his doorway. The Egyptians had a similar deity who controlled the terminal passage across the marshlands that divide this world from the other. He was the boatman named ‘Face-in-front-face-behind.’

Standing on the threshold, betwixt and between, is the zoomorphic anthropomorphism of the key that opens the gateway. It is the actual reflected image of the entheogen. The reflection of the mushroom in the mirror of the doorway would be the olive tree. Reflected also is the dual potential for the hero who is consubstantial with it and its deities. In one world, that of the goddess, there is the Medusa, queen of the sisterhood of Gorgons. In the other, that of the god, there is the subjugated goddess, Athena reborn as the daughter of the god, a female with no mother. She can forever testify that the male is the more important parent in procreation.

In fact, well into the Renaissance it was thought that the female contributed nothing to the developing embryo but her body as an alchemical vessel. The invention of the microscope seemed at first to confirm this, since it made the spermatozoa—semen-animal-visible to the eye. The early scientists were thus enabled to see the ‘little man’ or homunculus, or the ‘little animal’ or animalcule as proof of the male’s total contribution, an entire being already present in the male seed, even before it entered the womb.

If Athena viewed her face in a mirror, she would see the Medusa. The same would happen on the other side as the Medusa looked upon her own reflected image. In fact, the Medusa, as we have said, was not really a terrifying monster. She was ravishingly beautiful, and was so depicted sometimes even in ancient art. Cellini’s famous Florentine bronze statue of Perseus indicates that the tradition of her beauty persisted into the Renaissance: the only thing monstrous in the depiction is that the blood flowing from the decapitated head is metamorphosing into coral, as an indication of her fungal identity. Her beauty was the reason that she was so dangerous to men, who would not be able to resist her attractiveness or separate themselves from her after intercourse. It was Athena who made her appear ugly. On the other side of the mirrored image is Athena, a beautiful female that no man would fantasize as a sexual partner. She dressed as a man and was accepted as man’s best companion, attending him as a non-sexual girl friend on his masculine pursuits.

As the hero stands on the threshold, he is consubstantial with the entheogen and with the goddess and the god on either side. Here he is the half-creature, with a foot in either world. Here he has a botanical identity that partakes of the plant on either side. In one world is the mushroom of the Gorgon head. In the other is the olive tree of Athena. The creature in the doorway is both male and female, guardian of the passage through, either blocking the way or affording access to the shamanic flight.

It helps you open doors to yourself. You can see yourself for what you are.

—Ann Shulgin

Psychedelic Lay Therapist

This is the full ambiguity of the heroic persona. In psychedelic psychoanalysis, the psychoactive drug unlocks the door so that you pass through and ‘see yourself for what you are.’

Freud analyzed the complex dynamics of the nuclear family that resulted in the foundling fantasy. The child feels somehow out of place, unlike the siblings, alienated from the parents, probably somebody else’s child: a found child or foundling, like Oedipus, picked up by a herdsman on the mountainside where he had been abandoned by his parents; or like Moses, abandoned in the basket floating down the Nile. In the lore of the fairies, such a child is a changeling, a child of the fairy folk left in exchange for the one they stole away. A fairy child would have a secret botanical identity, a consubstantial shamanic sacrament.

This ambiguity about the hero’s parentage is essential to the mythical paradigm, often the reason why the hero passes through the doorway to find his other self. The hero on each side, in the reflected worlds, has a different set of parents.

Androcentric Scenario: As [the Watchers] continued looking at the women, they were filled with desire for them and perpetrated the act in their minds. Then they were transformed into human males, and while the women were cohabiting with their husbands they appeared to them.

—Testament of Reuben

Ritually, this was enacted in two ways. In androcentric theologies, a priestess could experience non-ordinary reproduction with a god. The human male through the agency of an entheogen became a surrogate for the god, possessed by the divine spirit as he inseminated the female. This is clearest in the myth of Hercules’ mother, who slept with Zeus, who had assumed the appearance of her husband.

Gynocentric Scenario: From the muses one separated. She came to a high mountain and spent some time seated there, so that she desired her own body in order to become androgynous. She fulfilled her desire and became pregnant from her desire. He [the illuminator of knowledge] was born.

Revelation of Adam

—Marguerite Rigoglioso

The Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece

In gynocentric theologies, the priestess through the agency of an entheogen generated the spontaneous meiosis of her ovum, mimicking the ultimate parthenogenic capacity of the creator goddess in birthing the cosmos from the Void of her vulva, essentially cloning or replicating herself. This latter scenario, although beyond ordinary human experience, is apparently possible through the use of various toxins, probably derived from serpent venoms, to stimulate the division of the ovum. If this proved impossible, it was at least the mythologized history of the event. In both birthing scenarios, the entranced state is essential. The cloning might replicate the mother as her daughter, but it could also yield the birth of a divine son demonstrating the containment of the male within the female, a return to hermaphroditic unity.

In the mythic paradigm, the hero actually has two fathers, a mortal and a divine surrogate. The phrase is italicized here as the first of an enumeration of recurrent motifs that we will develop. The father of Perseus was either his mother’s uncle—Proëtus or Proïtos, or the god Zeus. A maternal granduncle, which is the relationship of Proëtus to Perseus, is seen as an intensification of female lineage. The surrogacy of the divine father is always indicated by the chthonic or human circumstances of the god’s intervention, since in actual fact the entranced human enacted the divine inseminator. In the case of Perseus’s mother, Danaë, she had been buried beneath the earth, but Zeus inseminated her via a shower of golden rain. Alternatively, the mortal and physical Proëtus may have found his way into the subterranean confinement and became the father of the hero.

In the Renaissance, Titian depicted the dual agency as an alchemical theme. The heavens open above for the rays of divine empyreal illumination to impregnate Danaë. Beside her, the physical midwife catches a shower of golden coins. The painting was so popular that Titian made five versions for his noble patrons.

The mortal version of the two fathers motif, moreover, always has connotations of the gynocentric scenario. In addition to being the maternal granduncle, Proëtus has a wife with an honorific name of female dominance. She is called Stheneboea or ‘Cow-strength.’ Apart from being the twin of Danaë’s father and the putative father of Perseus, Proëtus is a figure of no importance. Stheneboea is the dominant force in their union.

There are also two mothers in the paradigmatic hero tale, but the mother is more problematic. No one can ever be sure about the father, but there were witnesses for his physical emergence from his mother. So the mother is a historical event, but what kind of woman is she? There are always two different possibilities, which thematically indicate two different mothers.

She always has a background that would indicate that she was the dominant partner in the sexual relationship with her mate. The weakling mortal father and dominant female could have been the parental couple, producing a son beholden to his mother. This was the case with one version of Perseus. He repeatedly had difficulty separating himself from her. Thus, he was born in an underground chamber sequestered with her. Then, no sooner born than he was confined with her in a chest and set adrift on the sea. Ultimately, this sequestration with the mother derives from the gynocentric scenario. He really is just an extension of her hermaphroditic self-sufficiency.

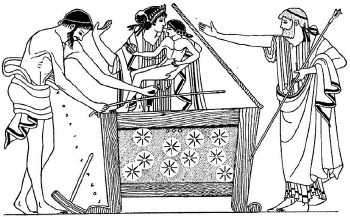

Danaë being confined in a chest with her baby Perseus and Acrisius, Danaë’s father

Danaë came from a whole sisterhood of women who rejected sex with males. They were called the Danaïds as a group, and Danaë is one of them, three generations later. They so dominated their unloved and unnecessary partners that they slaughtered them in their bridal beds—all except for one. She turned against her own kind and was named Hypermnestra, a name that designates her as a female who accepts her role as a ‘courted’ woman, open for the androcentric scenario of matrimony.