Francis Grasso

The groundbreaker

Interviewed by Frank in Brooklyn, February 4, 1999

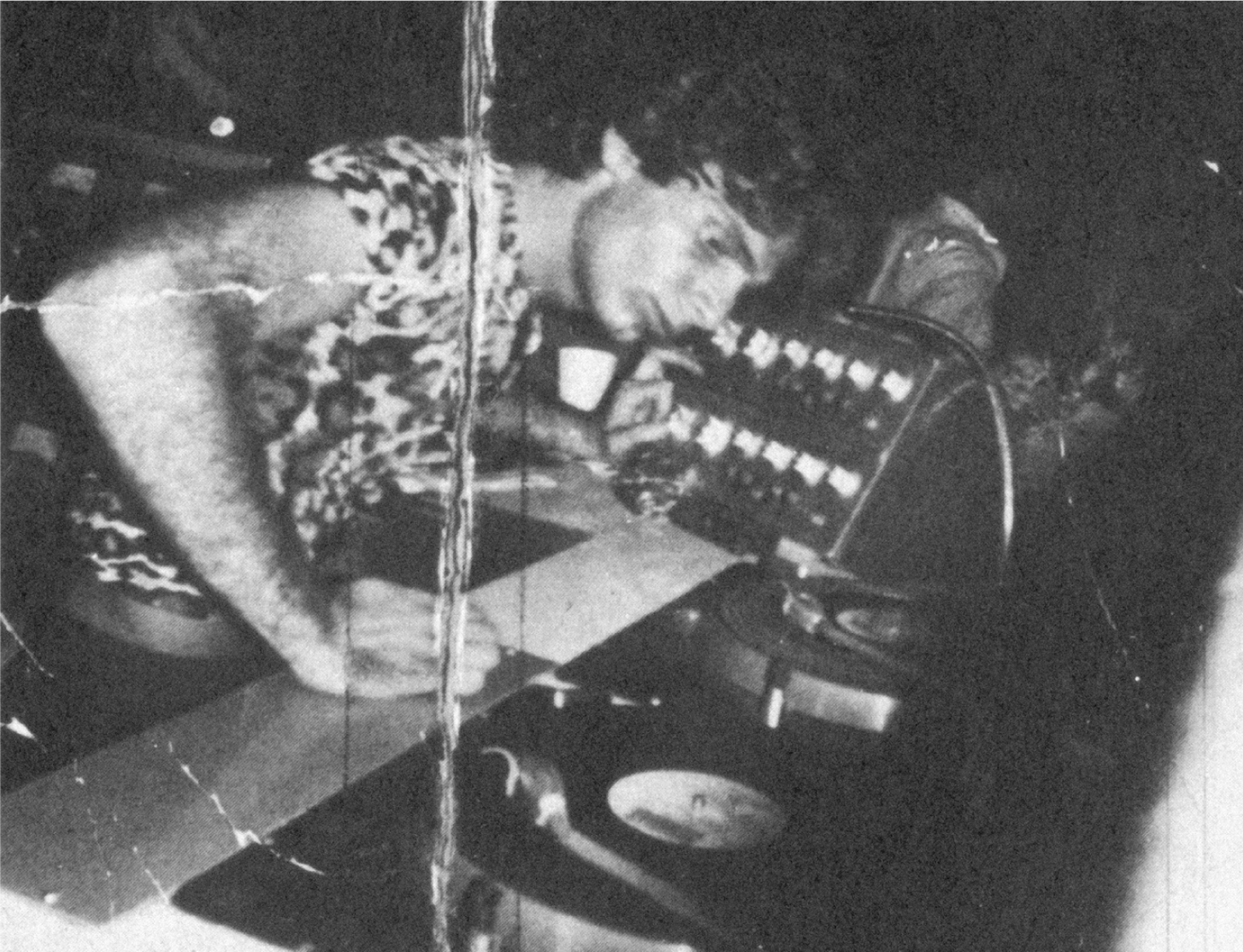

We found him in the phone book – the grandaddy, the pioneer, the first DJ to do what DJs do today. Before Francis, disc jockeys were technicians playing records one after another; after him they were performers programming whole nights of music, leading their dancers on a journey, and making them submit to an endless beat. He wasn’t the first to mix records, but he made it an essential skill as he stitched rock, soul, Latin and African tracks together for an adoring crowd. The central inspiration for the DJs who would create disco, Francis Grasso founded modern DJing by showing everyone just how much was possible.

The subway ride is a full hour into Brooklyn. The plan was to meet outside the Carvel ice cream store. But what will he look like? His voice on the phone conjured a big fatso bum. Anyone male, white and middle-aged gets the once-over, and then a 50-something groover, skeletally trim, with a brown leather jacket and a mane of long, fuzzy grey hair comes into view. Somehow it’s DJ Francis without a doubt. His face is a little skewed from the infamous mob beating, and he is obviously missing a few teeth, with several others in the wrong place altogether. This makes his voice sloppy, nasal and very quiet. Straight into Joe’s bar, to interview the godfather of DJing, downing glasses of draft Bud at 10am.

“There wasn’t really guys before me. Nobody had just kept the beat going.”

So you’re from New York originally?

Brooklyn. Born and bred, lived in many different places.

And you started off dancing, didn’t you?

Yep. One of the original Trude Heller go-go boys. Dancing on a little platform with a live band. It was in the Village, Sixth Avenue, on the corner of 9th Street. You had 20 minutes on and 20 minutes off, and you could only move your ass side to side because if you went back and forth you’d bang off the wall and fall right onto the table you were dancing over.

What were you wearing?

Slacks, you know and you’d have a partner, and they’d play ‘Cloud Nine’ by the Temptations for about 38 minutes [laughs]. It was the most exhausting job I’d ever had in my life. I was beat that night.

What was Trude Heller’s like? Was it ritzy?

Kind of. Kind of date-oriented. Couples, very few recorded records. She was just somebody who became famous, had her own nightclub. It was the hardest $20 I ever made in my life. I’m going home, my muscles were killing me. I remember on the train it was…

How did you get into that?

What? Dancing? I got three major motorcycle accidents, so I couldn’t co-ordinate my feet and the doctor suggested for therapy that I try dancing.

So it was a therapeutic thing?

Yeah, sort of. Very, very wacky sort of way. I never thought I’d go down that sort of trail, ’cos I’d gone to college for literature.

Where were you at college?

Long Island University.

You studied English Literature

No, I started out in math, I’d gone to a basically math high school: Brooklyn Technical. But I changed into literature. ’cos I had an English literature teacher she said I belonged there.

How did dancing turn into DJing?

Well, I was managing a clothing store on Lexington Avenue between 57th Street and 58th Street. It was upstairs. And the bartenders used to come in from a club called Salvation II, and I’d become familiar with Salvation and [manager] Bradley Pierce. So they said come by. Back then it was couples only. Eight dollars minimum. At that time they wanted to distract from loners, you know somebody who’d dance with the waitress. Because somebody dancing makes people who are a little laid back get off their buns and move. If they had a couple of drinks.

And there was a disc jockey named Terry Noel in Salvation II, and I went there on a Friday night, and he didn’t show up for work. Which later I found out why when he showed up at 1.30 and he’d taken acid. It’s not a good start to a Friday night! And they so liked me, they asked me if I wanted to try. I was pretty familiar with the music, and I had a ball.

“ I was at the Haven the night of the Stonewall riot. They locked the doors, the cops were clubbing people, they were throwing bricks and bottles. ”

What was the set-up? What were the turntables?

It was a Rek-O-Cut fader with two Rek-O-Cut turntables and the fader was just somewhere in the middle of both turntables. They were Rek-O-Cuts, probably not even in existence now, like radio quality at the time, motor driven. Not belt driven.

And all you had was a switch to cut between the two?

No. It was a knob, a fader. It was a fader, so you could do mixes. Sort of. If you knew what you were doing. But this was my first night.

And you took to it like a duck to water?

Basically, yeah.

Do you remember the first record you played?

I don’t know, but I had a hell of a good time. And they paid me a lot of money, and I said ‘Wow, they paid me this much money,’ and I would have paid them. I had that much fun. I know when Terry showed up he was fired.

Because he was unreliable and you were the new kid?

Well, I played better too. He used to do really weird things. Like he’d have the whole dancefloor going and then put on Elvis Presley. I kept ’em juiced. He would play bizarre records… He’s still bizarre, but anyway. But he showed up at 1.30, which is now Saturday morning, the club closes at 4. It’s not the right time to show up for work. And the owners had probably had enough of his attitude.

Can you remember the kind of records you were playing the first few times?

‘Proud Mary’ [by Creedence Clearwater Revival] was very popular. I played things like ‘96 Tears’ [by? and the Mysterians], Temptations, Four Tops, Supremes. There was no Jackson 5 then. Umm…

Can you remember the date when you first played?

Ooh no.

You remember the year?

1967 or ’68. Then Salvation II closed. So I was out of work. I was doing air conditioning work. And I was at this club in Union Square called Tarots, on 14th Street. And I asked them if they needed a disc jockey one night and they said go. And he just had a switch, he didn’t have a fader. You went from one to the other. And back then it was basically the same tunes. ‘Knights In White Satin’ was very popular.

How long did you play there?

Until the bouncer from the Sanctuary came to the club on a Sunday night. He turned around and said to me, ‘You know the guy we’ve got at The Sanctuary really sucks, so would you like to, you know, audition?’ I said sure. And at the time I had Brian Auger & the Trinity and Julie Driscoll. I went there with eight records; I thought if I can’t do it in eight I’m not going to do it all night long. And they were practising for a fashion show, with models. And in eight records I had the job. Next thing I knew I was at the Sanctuary.

And they were the wild years.

No. Those were the quieter years. It was when the Sanctuary was straight and it was mostly couples like Salvation II. What was really funny was that the manager of Sanctuary used to be the manager of Trude Heller’s. And we all thought the day manager and the night manager hated each other. But in reality they were shacking up, and they took off with like $175,000.

This is from Sanctuary?

The original Sanctuary, the original owners. The one in the church. It’s the one that was called the Church first. Open two weeks and the Catholic church got an injunction to close us down. ’Cos we had this mural that I would face that was unbelievably pornographic. And what was interesting about it was the devil, no matter where you stood in the club he was looking at you. Angels were fucking and… So what they did was they changed the name to the Sanctuary and reprinted the menus, and they stuck plastic fruit in various places, bunch of grapes here, you had red grapes, you had green grapes.

To cover everything up.

Yeah, ’cos it used to be some kind of German protestant church. But because this guy took the $175,000 they had to change hands. So they wanted to make the first gay bar. And they fired everybody, ’cos they didn’t want women, ’cos this was after Stonewall, suddenly… Well, it was the first time they’d taken the concept of a gay bar without a jukebox.

And not being secret…

Well, I remember the Stonewall. I was at the Haven the night of the Stonewall riot. I remember seeing the police come in a city bus. It was like wacky. They locked the doors, the cops were clubbing people, they were throwing bricks and bottles. It was a wacked out night that night.

Anyway, at Sanctuary, Shelley and Seymour came in [as new managers]. They had to get a new crew, or at least see who they were gonna keep or let go. So it became evident that I had the job. We used to close Mondays and Tuesdays, now we’re open seven days a week. And we’re packed.

I remember one time at the Sanctuary, when it was all gay, it was so crowded, and they were passing poppers around. Even if anybody wanted to pass out, there was no room. They were literally holding each other up it was so packed. ’Cos then we had a maximum occupancy of 346 people; we stopped counting at 1,600 at the door.

I used to go to the men’s room, and customers always tried to pick me up. I remember one time I was in a urinal pissing and this guy was in a business suit, and he said something to me, I said, ‘Employer policy is that employees cannot date customers.’ Then I started going to the ladies’ room ’cos there were no ladies. I remember one time there was a fellow named Alan who used to stand by the door and greet people. And somebody was doing an article and they said, ‘Do you get straight people here?’ and he went, ‘Yeah, there he goes.’

I had such power at that time. Two female friends of mine came to visit. They were just friends. At 2 o’clock in the morning, a weekday night, and I had James Brown Live At The Apollo on, 25 minutes and 32 seconds, and I said, ‘If you don’t let them in, you better get somebody up there to change that record.’ So after about five minutes of this stalemate, they let them in.

“ They didn’t know how to bring the crowd to a height, and then level them back down, and to bring them back up again. ”

Jane Fonda filmed the movie Klute there. She had a big argument with Seymour and Shelley because they wouldn’t permit lesbians in the club. I’m the disc jockey in the movie, and I had like three weeks work, doing the whole thing. It was fascinating to watch. Only thing is I was doing double duty: I was showing up at the movie set at 7.30, driving home, to Brooklyn, walking my dog, shave and showering, going back to work, till 4 o’clock in the morning. It took its toll.

I bet.

It was summertime and they would have a big table with coffee and bagels and doughnuts and everything you wanted. And then the cops came in, ’cos to get the feel of real hookers they had real hookers. Then they sent the cops in ’cos there was a lot of drug-dealing going on – in between takes! It was a lively crowd.

How was it through those times being the only straight guy?

Occasionally I had… fantasies! They would mistake you smiling hello as an answer back. But those were good years because I wasn’t engaged and I could devote all my time to my work. And I used to lift weights. I would do that every night, before I went to work. And I had my dog.

So you didn’t play at the Sanctuary that long?

Oh, about a year.

From what I’ve read, the Sanctuary was a wild place. Did it change?

It got wilder. In the summertime they were having sex in people’s hallways.

What about in the club? Did that go on?

Only me! ’os we were open all night. We’re a juice bar now. We lost the liquor license. So they had to be doing something. We were staying open till 12 o’clock in the afternoon – Saturday afternoon, and Sunday afternoon. And they’d be so smashed. In the summertime they’d be in peoples vestibules, in their hallways… It was a very… I have articles on it. Daily News used to call it a ‘drugs supermarket’.

What drugs were people doing back then?

Back then? The biggest drug people were doing back then was Quaaludes, the small ones, 300 milligrams, the pills. And you had the capsule which was 400 milligrams, and back then they went for $5 apiece. I had a pharmacist friend of mine and he used to get them in a sealed bottle and I’d sell them for a buck a piece, to my friends who came in. Made a lot of swaps for tapes, back in those days.

You would play high?

Oh yeah.

But no-one knew.

No-one knew. The idea was to show up, give yourself a facial, shave, shower. And talk to people like you’re a hundred percent normal. They never knew. I remember the first time I came clean with my mother. I said, ‘Didn’t you ever wonder?’ I had bought a house in New Jersey. ‘Didn’t you ever wonder, how I could come from work, take you someplace in Brooklyn, and drive back to New Jersey and go to work. Didn’t you ever wonder how I stayed awake?’

And what did she say?

‘Good point.’

And you had quite a following?

I’d get into a club with eight or nine people, didn’t pay, drink all night. I’d be out walking my dog, people would scream out my name on the street, in the supermarket. I would do average things, they’d yell ‘Francisss’.

That must have been great! Was it people you knew from the clubs?

You’d be surprised. If you put an average of 1,500 people in a room, for however many years I was playing: 17 years, a lot of people are gonna get to see you. I made a lot of fans in New Jersey. I made a lot of fans everywhere.

You were pretty much the first DJ that had that kind of following, but there were guys before you, so what were you doing differently?

There wasn’t really guys before me. Nobody had really just kept the beat going. They’d get them to dance then change records, you had to catch the beat again. It never flowed. And they didn’t know how to bring the crowd to a height, and then level them back down, and to bring them back up again. It was like an experience, I think that was how someone put it. And the more fun the crowd had, the more fun I had. See I really loved the atmosphere. I just wouldn’t have wanted to have been a customer. I loved being in the room, but I couldn’t see myself like being amongst one of the customers, being on the dancefloor, because I couldn’t handle that. I really hate crowds. But it’s fun to absorb it.

And to be in control.

Basically, yeah.

So how did you develop all of that?

I was a dancer! I was a dancer, so it was rhythmically… not hard. And I play a few instruments.

What do you play?

Well, I started on the accordion. I was young then. Then I went to guitar and then drums and saxophone.

Did you play in bands at all?

I played in high school.

You say musically it wasn’t a problem, and I can understand that: if you’re a dancer you know what you want to dance to. But technically it must have been a real problem… with the equipment you had back then.

Today you’ve got a disc jockey that puts on a 20-minute 12-inch. I’m changing records every 2 minutes and 12 seconds, on average. These guys don’t really work today. Unh-uh. I mean if you’re playing mostly 45s… If you’re dealing with seconds and minutes you’ve got to time everything. I had certain bathroom records, certain records you played only when you had to go to the bathroom.

What were they?

James Brown Live At the Apollo, then I used to play the Befour album, Brian Auger & the Trinity. I played a lot of English music. I had gotten a lot of imports over my time. I had a deal with the record store where I used to live. He would let me take all the new 45s, go in the back with this little portable Victrola, listen to them. And I’d buy them. And if I didn’t buy them I’d put them back. So I had a shot at all the new 45s that came out. Basically that was all there was back then. It had to be really good for me to buy an album. You had Booker T and the MG’s, you had Sam and Dave, you had your Memphis sound, had your Detroit sound, the Motown sound. You had to mix it up.

“ I dated Liza Minnelli for a while. I ran into her husband at the Salvation, he was at the urinal and he’s like, ‘I understand you kept my wife company while I was in Kentucky.’ ”

You pretty much invented slip-cueing, right? How did that come about?

Well, to tell you the truth, my good friend Bob Lewis was a disc jockey on the radio, at CBS, before they went to oldies, way back when they played rock’n’roll, and his engineer had taught me. But I found with the two slide faders, that I had gotten so good. You see the reflection off the record, you can see the different shades of the black. And I got so good I would just catch it on the run.

You would just drop the needle on it?

No I could catch it in the beat. The record’s spinning, you put the needle in it, right into it. And you just practised. I practised live, I guess.

So when did slip-cueing come in with felt pads?

Not till around the disco convention started [1975]. And the Bozak started coming in, the Bozak mixers. But I never liked the knob faders. The Bozak may have technically been more perfect, but you couldn’t do what you could do with slide faders. I don’t know why. You had to do the thing of turning your whole wrist, as opposed to just moving… With a slide fader one hand could do everything.

How did you programme the records?

You can’t be shocking in any way with sound. You can’t be overpowering, ’cos then too many people would notice. You start out with records like, say, The Staple Singers’ ‘I’ll Take You There’, now that’s a slow beat, and you build slowly and slowly, till you get them dancing fast. Like I used to play ‘Immigrant Song’ by Led Zeppelin, I loved playing that. I discovered a lot of records too: Abaco Dream, which was really Sly And The Family Stone, their tune called ‘Life And Death In G&A’ was a biggie. I discovered James Brown’s ‘Sex Machine’.

So what year were you able to beatmix, and completely segue?

I was able to beatmix right away.

That must have been so difficult with the records back then.

It was very difficult.

Did you have to remember exactly what tempo they were all at?

Well I know I had a basic variety of certain records in stacks. You bumped them into stacks; certain stacks would play a certain beat, like 2:4 beat, 4:4 beat, and you’d increase it. And when the drugs kicked in you just got crazy and the crowd got crazy.

So which club was the craziest?

I can’t really single out one.

They were all pretty wild?

Yeah. When I was at The Machine I really couldn’t see what was going on, ’cos it was like a stadium, the seating was on the left and right of me, and I was up there in my booth, and with the lighting in the booth over the turntables, I couldn’t see what they were doing, but the bouncers would tell me what they were doing: fucking and sucking, all that shit. Compared to these days, back then people were doing it a lot older. They were flaunting it, and carrying it around.

You mean the drugs.

And sexually and everything else.

What were your peak records?

‘You’re The One’ by Little sister, which was also Sly And The Family Stone. ‘Hot Pants’ was very big, by James Brown, when it came out.

How long were you at the Haven?

From ’69 to er… I can’t remember. Things were starting to happen. People were approaching me with business deals and stuff, always wanting to make a dollar quick. And I would make a deal with them, that they invest it in equipment, ’cos I had always believed I was only as good as my equipment. The only limitations I would put on myself was the equipment I was working with.

Who were you working with equipment wise, Alex Rosner?

At first it was Alex Rosner, then it was Dick Long. Not Bob Casey that much; he came in later on. Richard Long used to be Alex Rosner’s fix-it man. If something happened during the night, he’d send Dick Long out. Then they had some kind of disagreement or whatever and Richard, he outbid him, he outperformed him, and he out-equipment-wised him. Dick and I used to have some really serious conversations about sound. Dick was into perfecting it and making it more and more reliable. ’Cos you know if you have nothing [in back up], and it goes, you’re screwed. I didn’t even have a tape recorder back then.

Alex Rosner built you the ‘Rosie’ at the Haven, didn’t he. The prototype DJ mixer in a nightclub. What did Richard Long build for you?

I would say the first one was the one I had in my apartment. It was called Disco Associates; it had a triple volume control, single headset. Richard was really on the cutting edge. And gave me separate microphone input, and he was always toying with improving it.

When did you first have cueing?

I had that at Salvation II, but Tarot was sheer luck. They just had a switch. You didn’t have a fader so you couldn’t hear it coming in.

Was it a celebrity scene at Sanctuary? Did famous people come in?

Oh yeah, all the time. I dated Liza Minnelli for a while. When it’s people like that you’d just nod hello. Recognition is like… people think it’s really cool to say hi, but a lot of times it isn’t ’cos you’re expected to be always on. My second fiancée took a picture of me once, waking up. My hair was like this, you know. She’s caught me in the middle of a yawn. And she went, ‘This is the real Francis.’ Because I was so vain and my hair always had to be impeccable. Even my dungarees had a crease. I’m serious.

That’s what you wore in the booth.

At Sanctuary? No, I wore dress clothes. But at the Haven I made dungarees popular. The 501 Levis. Button fly.

“ I was caught so many times getting oral sex in the booth it was disgusting. I would tell the girls, ‘Bet you can’t make me miss a beat.’ ”

How did you meet Liza Minnelli?

In Salvation II, when I was starting out. She left me for a coke dealer. Her husband at the time was playing in a piano bar in Kentucky, Peter Allen, and I ran into him at the Salvation, and he was at the urinal – people like to discuss things at urinals… I don’t know. He’s like leaning over my shoulder, he’s like, ‘I understand you kept my wife company while I was in Kentucky.’ Back then I didn’t snort anything. Back then a wild night to me was a wine and a little 7-Up in a glass.

I knew a lot of famous people. Knew Jimi Hendrix very well. In fact when he died, his main old lady, after she flew his body back to Seattle, when she came back to New York, she moved in with me. She wasn’t a fiancée, a little off the wall for my taste! Not too stable. But nobody was stable back then.

I remember one time I ran into Jimi in the mens room at Salvation II. He was so stoned, he had his dick out and he couldn’t remember what to do with it after he’d finished peeing. It wasn’t a very large bathroom, so I said ‘Jimi, it’s Francis, what are you doing?’ ‘Trying to wash my hands.’ I said, ‘don’t you want to put something away first?’

That’s when he started hanging out with Buddy Miles, got into that heroin shit. Buddy Miles had the gang with the dark sunglasses at night, the long leather coats, the hoodlum look. People like Jimi they get run out of the way, over the deep end. I remember a time he was playing in Houston, and going over to the stadium he took five tabs of sunshine acid. And to him he sounded good. They booed him like crazy.

Were you able to see your influence on other DJs?

Yeah. I taught two of the most prominent: Michael Cappello and Steve D’Acquisto.

How did you meet up with them?

Hanging out. From them coming in as customers. I basically needed somebody reliable and who knew what they were doing, at least had an idea. I had to teach somebody. I was teaching in secret because it was really hard to do what I do. I may teach you the basic moves, but it’s your interpretation that makes or breaks you.

Steve D’Acquisto has stories of the three of you staying up for three or four days.

Just three or four? [laughs]. I remember the first time they replaced me. Of course I had to teach somebody, when I had the walking pneumonia, in Sanctuary. And I went to work that Sunday night. I was in another room, I was so sick. The family doctor came to my bachelor apartment, and he said, ‘You got walking pneumonia, you can’t go to work.’

Oh shit!

That’s what I said. But having a dog always kept me, you know, stable. Responsibility! I’d never stay out and party. Go home. Probably why I’m still alive today.

Wasn’t there a story that you got really badly beaten up? What was that?

That was opening up Club Francis. It had to be around ’73, ’74. Over the old Cafe Wha. My nose has been broken about 12 times. Least that’s when I stopped counting.

Was it another club behind it?

Yeah, the Machine.

Because you were so successful.

Yeah, they didn’t want me to leave. And they had the Mafia sit-down. The guy in the corner had instructions not to hit me, but to scare me. Only the guy they sent got carried away.

Shit! How bad was it?

“ Michael would constantly scratch my records. He’d pass out on Tuinols on the turntable; we had to get another copy. ”

Bad. Kept me home for three months. I remember sitting in St. Vincent’s hospital. I told the cops that I had went out to get a breath of fresh air, from the club, and these guys were coming up MacDougal Street, and they hit me with beer bottles. And I remember, these two doctors, in the emergency room of St Vincent’s hospital in Manhattan, they said, ‘Shame, must have been a good looking guy.’ I had to reinvent myself so to speak, sitting at home for three months. And really when I walked my dog people thought I was Frankenstein. I was a teenage Frankenstein, with the bandages the whole bit.

Was that the end of Club Francis?

No that was the beginning. That was the first night of Club Francis.

You must have been pretty discouraged

Well, I broke up with my fiancé. I was gonna get married. Broke up with her.

That was fiancé number…?

Well, we never quite got it, we just sort of eloped one night actually. My cousin walked into Club Francis and he was with this ex-nun. And I said, ‘Dierdra, let’s get married.’

She was an ex-nun?

No, my cousin’s girlfriend was an ex-nun. Dierdra was a Playboy bunny; she worked in the gift shop. And she said, ‘Are you serious?’ and I said, ‘Yeah.’

So where did you play after Club Francis?

I went back to the Sanctuary. And they were starving, they were dying. It had become a juice bar. When I left it had had alcohol, they were open til like seven in the morning.

It was still a gay place?

Basically, but they had more women there. ’Cos they were harder up for money. It was like a dungeon: depressing. And I just turned it back on again. This is ’72, ’73 maybe. Like I say I went back and forth to Sanctuary a lot.

And were they the real wild years?

Oh, I was caught so many times getting oral sex in the booth it was disgusting.

While you were playing?

I would tell the girls, ‘Bet you can’t make me miss a beat.’ Gave them a little challenge and away they go! In fact in the Sanctuary one time the manager walked in. He walks into the disc jockey booth, and he sees this girl on her knees, chick’s head’s going up and down, and I says, ‘Don’t bother me now. If you’re gonna yell, yell later.’ I had such an amazing experience with women over the years.

What were the other rewards? You got pretty well paid?

Oh I was making a lot of money. I think my drug bill was – at that time drugs were a lot cheaper – was about 250 a week. And that was for what I’d give away. I’d go to work I’d have 20 joints. I’d buy pot by the pound, bring 20 joints to work with me. Buy an ounce of speed.

What kind of kick did you get out of DJing personally?

It was just feeling, the excitement, the electricity that was in the air. It was just phenomenal. I would have paid them. It was that much fun.

What were you aiming for when you were playing?

That high. People should have the same amount of fun I’m having.

Did you practise a lot.

I never felt that I’d done a good job. I always felt I could have done it better. I still do that today. Always doubting myself. There’s always room for improvement. It wasn’t until I moved to this neighbourhood that I didn’t have a disc jockey set up. I built a booth in my living room.

What were the best times?

I try to learn something from everything. Even after the beating I tried to learn something from it. Taught me a lot of lessons in life – for what use I have no idea.

Did you feel like you were really connected with the dancers?

For years. For years I felt like that. Then that line dancing shit started. And that syncopated sound. They put everything to a disco beat. Like ‘What A Difference A Day Makes’, they had some great tunes, but making disco out of it, it just didn’t work. It didn’t have the real live sound. And in my opinion today’s musicians are nowhere near as good as my generation’s musicians. I mean back then it was magic. It was great until the middle ’70s when everybody got into disco and Saturday Night Fever, and then it became so routine and mundane, and everybody wanted to be a disc jockey. Like, hey, everybody’s a disc jockey. Everybody and their mother’s a disc jockey actually.

You made mixing an important part of DJing. Can you tell me some of the records you were mixing together?

I had been known to make mixes like Chicago Transit Authority’s ‘I’m A Man’, the Latin part, into ‘Whole Lotta Love’ by Led Zeppelin. I played a lot of African music. I started African music in nightclubs. Michael Olatunji’s ‘Drums Of Passion’. It bothered me when Santana came out because they didn’t give Michael Olatunji credit for ‘Jingo’, and it’s not even pronounced that way. It’s pronounced J-I-N-L-O-B-A and in Santana’s album it’s J-I-N-G-O, and it wasn’t until the third release of their album that they put M. Olatunji credit for ‘Jingo’. Probably the best thing Santana’s ever done.

What were some of the other big mixes you would do?

I was responsible for bringing Osibisa’s ‘Music For Gong Gong’, Earth Wind And Fire, ‘Sweet Sweetback’s Badaaaasssss Song’. Mitch Ryder went with the Memphis sound. Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels went to Memphis and it was called the Mitch Ryder Experiment, which was very good. I would lay down say ‘Soul Sacrifice’ by Santana, and then put the live Woodstock version on top of it. And extend it, and go back and forth. The Woodstock version is just a little bit faster.

You would totally overlay the two things? How did that sound?

Phenomenal! It was actually the first reverb anybody had ever heard of. But it wasn’t. And the owner had these wooden discs coming out of the wall, where I would hang my 45s, ’cos back then you played 45s.

This is where?

The Haven. I used to have junk records, you know, so whenever I’d throw a temper tantrum I’d take a record, and the wall was brick, and I’d throw it and break it off the wall: ‘See what I think of that idea?’ It was a good effect. He didn’t know they were junk records.

Did you ever use two copies of the same things and extend things?

‘You’re The One’ [by Little Sister] was similar, with part one and part two on the other side.

So how would you work that?

Well, you always get two copies, ’cos you only had like two minutes.

You had two copies of everything?

Mostly. If they were really big, like James Brown’s ‘Hot Pants’, that was big, ’cos people wanted to dance, it’s summertime, the tube tops were in, no bras, the whole bit.

If you had two copies, how long would you work it?

I’d never push it more than three times. On Little Sister’s ‘You’re The One’, part one ended musically, part two would begin with a scream, so you could blend right into the scream, and then go back to ‘…You’re the one…’ Or the scream twice. Play it twice, part two, flip it over and play it, twice. They didn’t know I was playing two 45s.

But you didn’t cut it up any more. You didn’t say, ‘Right I’m gonna play the intro, then another intro,’ that kind of thing. Did you do that?

Occasionally. It would depend. I just basically tried everything there was to try.

Did you get any interest from the record companies recognising the promotional value of what you did?

Yeah, some, but back then everyone was caught up in their own thing. It was like, I’m doing my thing, leave me alone.

Did you know any of the producers or the musicians?

I was an upstart. I went to Colony Records just like everybody else, and I bought my records and then I went to work.

There was no way you could tell the labels: why don’t you extend things or make it like this…?

I told them: the manager of the radio station, CBS FM; I said ‘What you need is to stop putting commercials between records, and tie records together.’ I made a tape for CBS, of what I could do. And they did adopt that idea, but then the station changed to oldies. But I did have my own radio show.

When was that?

1968 ’69?

On CBS?

No, WHBI. Michael used to come with me…

Michael Cappello?

Yeah. We broadcast from Jersey City, but we used the Empire State Building transmitter. So I’d have to go through the Holland Tunnel, it was a couple of blocks from there. That was pretty interesting, couple of times I brought my great dane in the booth, you could hear the rustling of the dog under the table. I’d say things and I didn’t realise the mic was on, and I was on the air. Got a letter from the FCC. I wrote back on the inside cover of a pack of rolling papers. A quote about freedom.

And you never got into remixing or production work?

I sort of did that live! You know they went to 16 tracks, then to 32. Equipment, technologically, things were going just so fast, leaps and bounds on the nightclub scene.

What were the big changes in the booth, technologically?

You had the crossover network separating the midrange, treble and bass.

Did you play with that?

Oh yeah.

When did that come in?

I was doing that way in the beginning. They just didn’t know I was doing it.

You had crossovers back then?

Not crossovers, I’d just play with the treble. If a song was poorly recorded, and needed treble, just crank it up, and lower down the bass a bit. ’Cos back then a lot of 45s were poorly recorded.

It was funny because I’d listen to dance music when I got home. I listened to the Moody Blues, or King Crimson, Yes, Zeppelin. I discovered this record Andwella, ‘Hold Onto Your Mind’. I always felt that if you had a little bit of a Latin beat it made it easier to dance to. It catches the audience’s ear. Andwella was like that. Colony Records didn’t even know they had it in the basement.

And the club had the records at that time; they didn’t belong to the DJ?

The club had the records. For a long time that was the way it always was.

So you changed that.

I changed that.

That meant you were more independent then, because you had your own collection.

I also had a friend that worked at Colony. He charged me a dollar a piece. ’Cos Michael would constantly scratch my records. He’d pass out on Tuinols on the turntable; we had to get another copy. If you fall on top of the needle you’re gonna gouge out the grooves of the record. One record I got through seven copies. Jimi Hendrix and Buddy Miles, the first album they did together at the Fillmore, had a lot of copies of that.

So what happened to your records then?

They were stolen when I was in hospital. And my equipment.

Do you think that was connected?

It was my next door neighbour. He convinced my family he was gonna hold onto them for me. He didn’t tell anybody he was moving.

That must have been heartbreaking.

Well, considering I took such care of my records.

And you had so many

Yeah, over the years you get quite a collection.

Have you built it back up.

I just mix cassettes now and again. I really don’t listen to dance music.

“ Back then if you met somebody at 3 o’clock in the morning, they were a freak like me. Now they’re just a degenerate. ”

You don’t have the old records you used to play?

Not that much. I remember… When Barry White came out I said he’s the poor man’s Isaac Hayes. Saw him a lot. Used to see – I forgot his name – from Blood Sweat and Tears, used to meet him in the Village. Back then if you met somebody at 3 o’clock in the morning, they were a freak like me. Now they’re just a degenerate. And they’re looking to rob you.

When did you call it a day?

1980, ’81.

And that was because…?

I didn’t quit ’cos it was a money issue; it just wasn’t the same any more. It became work. I got disgusted… this bullshit. And the people had changed. As it turns out I was lucky to get out, ’cos it was just the advent of AIDS and I had always thought that AIDS would develop into a heterosexual disease. And Richard Long died of AIDS. I lost 38 friends. Then I found out Richard Long died, made it 39, all of AIDS.

What’s your greatest memory behind the booth?

I remember when I was working at the Haven, the Sanctuary manager, Michael Crennan, called me up and said somebody’s been fooling around with the cartridge in the back. And could I take a look. I said I could stop up there before I go down to the Haven to work. And when I walked in and the customers saw me behind in the booth, they all applauded; there was this big cheer. People stood up, the house lights were all on. I’m like [shrugs] I’m not staying.

Did you sell tapes back then, mix tapes?

Well people didn’t want to spend the money. They’d want to buy a reel-to-reel. If you had to buy the records, it’d cost you 500 dollars. Without my talent. People were interested, they just weren’t into the money.

Did you ever make tapes and sell them?

I traded. For clothing. I’d make like cassettes for clothing and things like that. But as far as going into making a tape, I’d do it for friends. If somebody… Albert Goldman had a 4th of July party one time; I made a tape, reel-to-reel that he played at his party.

You were friends with him?

Yeah.

Did he get it right in his book Disco? Is that all correct?

Basically he got it right. The Penthouse article that it was taken from, my mother went out and bought so many copies. She framed the picture of me. Its like a centrefold, they took the staples out. So you see this naked broad Ginger and then the next page is me.

How did you meet up with him.

He called me up. And he came to work one night and sat in the booth, and he said, ‘Now I see what they mean.’ He said he’d spoken to a lot of disc jockeys and nobody could exactly explain what they did, and I was the only one that was able to… that made sense.

How come you never wrote a book about it all?

It’s not over yet. My life is an adventure.

What do you think makes a great DJ?

A lot of persistence. And a lot of being aware of your surroundings, and you gotta have a natural feel for rhythm.

What makes a bad DJ then?

[laughs] The wrong records.

© DJhistory.com

FRANCIS GRASSO 26

IRON BUTTERFLY – In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida

RARE EARTH – Get Ready

FOUR TOPS – Don’t Bring Back Memories

LITTLE SISTER – You’re The One

CHICAGO TRANSIT AUTHORITY – I’m A Man

FOUR TOPS – Still Water

OLATUNJI – Jin-Go-Lo-Ba (Drums Of Passion)

BOOKER T & THE MG’S – Melting Pot

TEMPTATIONS – Ball Of Confusion

ANDWELA – Hold On To Your Mind

ABACO DREAM – Life And Death In G&A

OSIBISA – Music For Gong Gong

JAMES BROWN – Hot Pants

MITCH RYDER & THE DETROIT WHEELS – Liberty

BRIAN AUGER, JULIE DRISCOL & TRINITY – Indian Ropeman

SANTANA – Soul Sacrifice (live)

CAT MOTHER & THE ALL-NIGHT NEWSBOYS – Track In ‘A’ (Nebraska Night)

THE MARKETTS – Out Of Limits

TIMEBOX – Beggin’

ELEPHANT’S MEMORY – Mongoose

THE DOORS – The End

CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVIVAL – Proud Mary

? & THE MYSTERIANS – 96 Tears

LED ZEPPELIN – Whole Lotta Love

MOODY BLUES – Knights In White Satin

TEMPTATIONS – Law Of The Land