Steve D’Acquisto

Disco’s radical

Interviewed by Bill in Manhattan, October 5, 1998

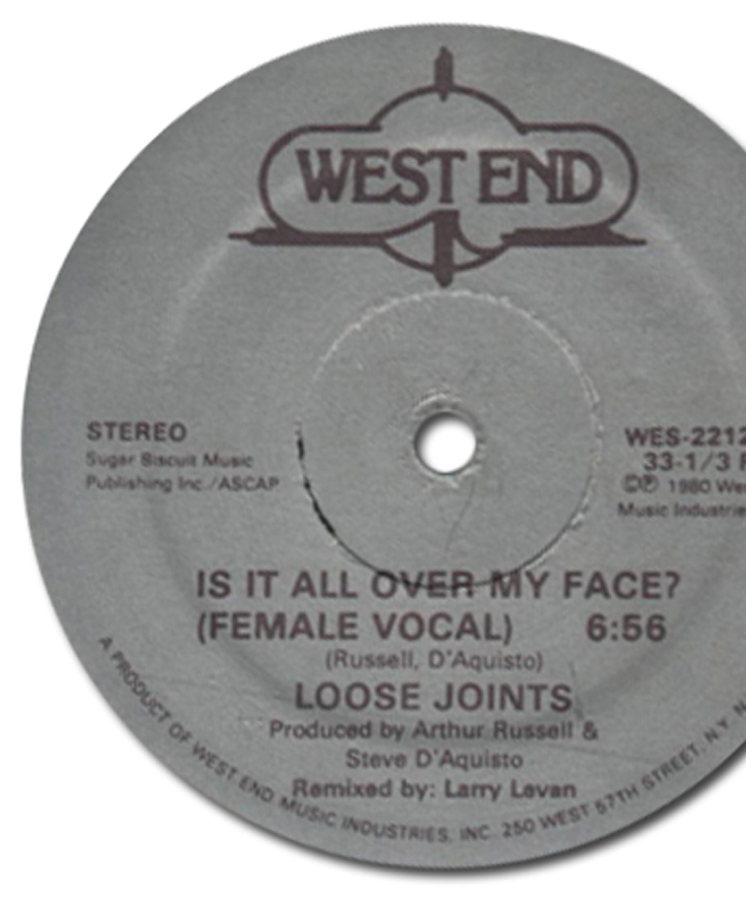

Steve D’Acquisto was disco’s firebrand, a revolutionary who saw it as much as a movement as it was a style of music. Steve saw a DJ booth in place of the soapbox and found his own Communist Manifesto in the lyrics of Gamble and Huff. He is from the very first generation, a sparring partner of Francis Grasso and Michael Cappello. Although he built a reputation as a great DJ at places like The Haven and Tamburlaine, it’s as a facilitator and cheerleader that he will be remembered, nurturing and helping DJs and artists like David Mancuso and Arthur Russell, with whom he made the Loose Joints records for West End.

Sadly, Steve died of a brain tumour in 2001. He played what was probably his last ever gig at the New York launch party for our book Last Night A DJ Saved My Life, an incredible honour, not least because his mother had passed away a day or two earlier. With a beautiful set of fragile, poignant disco, he made the music a tribute to her.

Our paths first crossed in 1996 at a convention in Chicago where, despite his greying hair, he had an incredible enthusiasm for music. The second time we meet is in New York in Charlie Grappone’s Vinylmania store on a beautiful fall morning. He’s tall, with spiky hair and a gentle yet distinct New York accent. Although he’s very laidback, you can still feel a personality coming through that’s as spiky as his hair, and indeed down the years his militancy has alienated some and pissed off plenty. Today is Steve’s 55th birthday.

“Discotheques were going to become temples. They’ll replace religion. You stay at the party all night, and that’s how you get your religious training.”

Tell me little about your background.

I was born in Brooklyn, my dad would be 102 years old if he were alive today and he had quite a record collection. A lot of Italian music and waltzes. He was born and raised in Sicily. He was a merchant seaman. He bought gramophones. I have an older brother and sister and they also loved music. I was born in 1953. I’m 55 today actually. My brother bought me an old Traveler Victrola which was electric as opposed to crank up. My parents told me that by the age of three they had a party trick where they would ask me to put on a record and I would. I was born before TV, so I listened to radio dramas and comedy shows.

So I started collecting records as a kid. Other kids would ask for toys on their birthday. I asked for records. When I was eight, nine, 10 I could name what was going to be number one. I had an ear for public taste. I have 6,000 78s. I can’t even count the 45s.

Tell me about the radio DJs you listened to.

The first one was Martin Block. This was before rock’n’roll. He was an institution here in New York. He was on WNAW-AM. He was also influential in terms of live broadcasts of swing bands and one of the first people to start playing records on radio, as opposed to live music. Because of Alan Freed I fell in love with Elvis. But I was also buying Doris Day. I heard ‘I Want You, I Need You, I Love You’ by Elvis, which blew me away. That was the last 78 I bought. And the first 45 I bought was ‘Let The Good Times Roll’ by Shirley and Lee, which was also an Alan Freed record. Ultimately it got banned because of the lyrics. It’s a great party tune. It’s all about sex and fucking. But those things existed on records before, like Bessie Smith’s ‘Nobody In Town Can Bake A Sweet Jelly Roll Like Mine’. That’s all about getting fucked. Fats Waller’s ‘Hold Tight’ is all about cunnilingus. ‘Hold tight I want some seafood mama.’

I had Little Richard records. The Platters. All the doo-wop comes from what the Ink Spots and Mills Brothers were doing. Penguins, Cleftones, Orioles. Alan Freed took us into a whole new world. Subsequently, there was Peter Tripp. When Alan Freed left, or got fired, which we thought was bizarre, Murray the K came in and took over from Freed.

Do you think Freed was persecuted because he championed black music?

Yes. Absolutely. No question about it. They went after him because he was ruining the youth of America. He was taking their children and turning them on to this bizarre music, because at that point in time it was considered the devil’s music. I saw an Alan Freed show at the Brooklyn Fox on Fulton Street – now torn down – with Fats Domino, Everly Brothers, Joanne Campbell, The Platters and Little Richard. The crowd was mostly black. That is etched in my memory. They were trying to kill it, but it just wouldn’t go away.

Where did you hear Symphony Sid?

He was on the fifteens on the AM dial. At that point I was into Billie Holiday. We would listen to it at a friend’s house. I’d already started to collect Billie Holiday and Bessie Smith records. The first album I bought of Billie Holiday was The Golden Years, a two-record set on Decca. She said on the liner notes her influence was Bessie Smith, so I went and sought out those records, too. Here I was going between jazz, rock’n’roll and pop.

What we’re you doing for living after you left high school?

I’m a licensed funeral director. At 17 a friend from childhood had a father who was opening up a funeral parlour a couple of blocks from my house. His father took a liking to me and I was there for seven years. Then in the ’60s I took LSD and that completely changed my life.

“ I was driving my cab and taking amphetamines so that I could drive 12 hours straight. People had to get in the car while it was still moving; that’s how fast I was moving! ”

When did you first take that?

In 1966 or ’67. At that point we were listening to Rosko on WNEW [not to be confused with Emperor Rosko] and Scott Muni early on. Roskoe was the most influential of the ’60s DJs. He played rhythm and blues, long tracks, really WNEW was the first station to start playing album tracks rather than just the singles. You started hearing five, six and even ten minute tracks. ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’ by Iron Butterfly was probably the longest record to be on the radio; ‘MacArthur Park’ was another one [by Richard Harris]; ‘Get Ready’ by Rare Earth. Ultimately, we would end up playing these records in clubs. Early on we played ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’; we played ‘Get Ready’.

Before I go on I should go back to Francis [Grasso].

So here I was, infatuated with LSD and marijuana. Smoking and dropping acid all the time. Started to go out to clubs, gay bars like Stonewall. So I was around when the Stonewall riot happened. I was there a few nights before, but not on the night. I was on blue cheer LSD that night; beautiful colour, beautiful colours as well.

While I was waiting for my license I went out and drove a cab. I didn’t want to do embalming, but my parents had spent all this money. I was driving my cab and taking amphetamines so that I could drive 12 hours straight. I was the highest cab driver at the company. People had to get in the car while it was still moving; that’s how fast I was moving! I dropped somebody off at the Haven, at 1 Sheridan Square, which I later found out was where Café Society was, where Billie Holiday had her biggest successes.

So what did this guy say when you were dropping him off?

I asked him, ‘Where you going?’

He said, ‘Oh, it’s an after-hours.’

It was an illegal after-hours, because they used to sell alcohol. Didn’t have a license. Mmm, wonder what this is all about? So I went down there…

Was this after Stonewall?

I believe it was. Or around the time of Stonewall. It was late ’68, early ’69. I had long hair right down my back at this point. So they let me in, figuring I was some kind of freak. And I met Francis, who was the disc jockey there, and it was a whole new world to me. Here was this guy, playing records, mixing records, doing all these great things that had never happened before. On radio, basically the fade would come and the new one would come in. Francis had a lot of records, but I had more. And we used to chat, and we got friendly. By that point I’d be going every night. I’d book the cab till 3am, didn’t have to bring the cab till 5.30 or 6, so for two hours I’d go hang out with Francis. And we’d speed together. He was a speed-freak as well, loved speed. I always had good drugs, he always had good drugs and we became very friendly to the point where I was doing lights.

For six months that went on. One night I was at Francis’s house and he’d been playing for two weeks straight and his alternate hadn’t showed. They called Francis and told him he had to come in; it was a Monday night and Monday and Tuesday were the off nights. So Francis says, ‘I can’t do this.’ You have to remember these weren’t six-hour nights, they were 12-, 14-hour nights and it would depend on how high people were as to how late the club stayed open. He looked at me and said, ]Do you wanna go play some records? Just make believe you’re me.’ So I did and I liked it.

What equipment did they have there?

They had two Rek-O-Kut turntables, two piggy-back Dynaco amps and they also had these giant speakers that belonged to Felix Pappalardi, who was one of the producers of the band Mountain. Somehow or other, Nicky Di Martino, who was the owner of the club, was owed money from someone, or whatever, ended up with these giant speakers. Great-sounding things. So we were actually using high-end, hi-fi amps.

Did you have a mixer?

No, it was two integrated amps, literally on top of each other: piggy-back. They had bass and treble controls and volume controls. Both connected to that same set of speakers. No cueing system. You had no clue about the record coming in. You had to listen over the record that was playing, so you could hear. You could actually hear over the PA what was happening. You really had to know your records. Because a lot of these things had long intros, which you didn’t want to have, like some of these Gladys Knight records, if you listen to ‘You Need Love Like I Do’, there’s a long intro before it comes in. We used to use the downbeats where the record came in to actually introduce it. I guessed we worked for about a year-and-a-half without headphones. We were always trying emulate radio DJs, listening to the radio, Francis and I.

Michael Cappello started a few weeks after I did. Michael was a patron at the Haven. Michael was a fabulous person, extraordinarily handsome and just a good buddy. Michael and I were brothers for years and years. I met Michael sitting on a stoop over on Jones Street; he was completely whacked out of his mind on speed and LSD, and I was stoned. I’d seen him at the club and we started to chat, and I found out that he had a lot of records as well. And Francis was moving, and I was taking over the Haven, so I said to Michael, ‘Come and play records.’ That was when Francis moved to the Sanctuary. Michael ultimately went to the Sanctuary. I ultimately went to the Sanctuary. We were all moving back and forth. The three of us running clubs in the city.

Francis is straight isn’t he?

Yes, Francis is straight. Although everyone used to think about it. But he is straight, though I think he would have gone to bed with Michael Cappello at some point. He was going with a woman at the time; she was taking care of him. He was really handsome and had such sex appeal it was scary. He handled it pretty well. Michael was just a kid. He was like 16 years old when he was playing records, and as far as I’m concerned Michael Cappello was the best DJ who ever did his thing. I could listen to Michael hour after hour, night after night and he never bored me. Always inventive, always genius, extremely clever.

Although he was young he was very worldly. He’d been hanging out in the city a long time and because he was so beautiful and handsome, girls would take advantage of him when he was 12 or 13 years old. By the time he was 16, he’d seen a lot. Women, staying out all night, moving in with women at 14 or 15. Francis was also his senior but not as old as me. But Michael was just phenomenal. He was a great DJ and a spectacular entertainer and a terrific head for music. He discovered some things: ‘Give It Up Turn It Loose’ was one of Michael’s. We would all go out looking for records together.

Where were you getting your records from?

Well, Francis used to have this place on Church Avenue and Flatbush avenue in Brooklyn, where he used to buy a lot of his records, and at that point this was a transitional period where it was becoming a more black neighbourhood. This guy had a lot of good stuff: Dyke & The Blazers, original Kool & The Gang stuff on De-Lite like ‘Funky Man’, Lou Courtney’s ‘Hot Butter ’N All’ and ‘The Chicken’ by Jackie Lee. All these funk obscurities. And all these album cuts too. We would all go there. Then we started going to Downstairs Records on 42nd Street, where Nicky worked. Nicky was just a great guy, and he turned us on to a lot of good music. We’d go to Dayton which was on Broadway and Twelfth, and find albums there.

Where you still playing some of the psychedelic rock stuff, too?

We sure were. We were playing Rolling Stones’ ‘Sympathy For The Devil’. From Let It Bleed we’d play ‘Live With Me’ and ‘Gimme Shelter’, we’d play Led Zeppelin like crazy: ‘Whole Lotta Love’. The Doors’ ‘Peace Frog’. ‘The End’ was the closing record for years.

At the Haven?

At the Haven, the Sanctuary and all kinds of places. It was a tremendous record, really long and people would just… come down. At least come down enough to go to the next place! There were other after-hours joints that started at eight in the morning. The 220 on Houston Street was one.

Were these primarily gay?

All the freaks. You’d have gangsters, drag-queens, there were absolutely no barriers. I come from an era where men couldn’t dance with each other. There would be a light system which I ultimately introduced to the Loft when we were having trouble with the police in the mid-’70s. They would flip a light into the back rooms because all these places had bars and they had dancing jukeboxes in the back and listening jukeboxes in the front. So they would just turn the lights on and you knew you’d have to stop dancing with each other. And they would pipe in the music from the front jukebox and stop the music from the back jukebox. And we used to put money in the jukebox to dance. This was called the Magic Touch in Long Island, in Oceanside. Gay people used to find these friends, men, women, whatever, and say come with me to this bar and there would be 20 of us in the bar and the straight guys would accept us and it would be a cool experience.

So when did Fire Island start to happen?

Fire Island happened when I was at Tamburlaine. I remember Bobby DJ turning me on to ‘Shaft’. He was the first person to play ‘Shaft’ and he was playing at the Monster and other places on Fire Island, like Ice Palace. Before the transition to mostly black music, when rock’n’roll started to peter out there wasn’t really a radio station where you could listen to all of these odd records that we were finding. We would sit at Nicky’s place [Downstairs Records] for hours on end and just play records. We’d be speeding. Sometime, Michael, Francis and I wouldn’t sleep for three or four days at a time. Go on and on, snorting speed and crystal meth. We were very serious about our speed! We had to though: we were playing 12 or 15 hours in a night, every single night. We all hung out together: Francis at Sanctuary, Michael and I at the Haven.

Did you go to the Sanctuary or were you working?

If I got off early, or Michael was playing I would go to Sanctuary. Go back, listen to Michael. Life was a club, 24 hours a day.

Describe the Sanctuary.

Sanctuary was the most incredible of all the places in its appearance and the structure. The DJ booth was on the altar, so it was a real ego trip. And they had these four giant speakers hanging from the rafters. It was a peaked roof and these four big speakers facing down on to the dancefloor. Then they had, on both sides, these balconies with tables and chairs. Then the bar, you’d have to walk through these two big archways. So you’d come in, you’d go through the bar, go through the two archways and there would be the dancefloor. And at the very end, there would be the DJ booth. That was the first time we had cueing systems.

Who came up with the idea?

Francis I guess, but I really don’t remember. The first time there were speakers in the booth, like they have now, was through Alex Rosner.

What was the composition of the crowd?

Sanctuary was mixed again, because Francis took some of the crowd from the Haven; and Sanctuary had its own people from before – I think Don Findlay was DJing there, maybe even while Francis was still happening. Don was an alternate. Don was very handsome man, loved records, and I have some Don Findlay tapes that I treasure.

“ Sometimes, Michael, Francis and I wouldn’t sleep for three or four days at a time. We all hung out together. We were playing 12 or 15 hours in a night, every single night. ”

Do you have any tapes of your sets?

Yeah, but I don’t know… We were so busy making cassettes, but the cassettes only go back to Le Jardin really. Never really made tapes at Sanctuary or Haven, we didn’t have the facilities. When some of these clubs got cassette recorders in, they started making tapes. I don’t believe I have a tape of Tamburlaine. Michael has a lot of tapes. John Addison [owner of Le Jardin] used to sell our tapes. We never got a penny from it. We weren’t making any money.

Was the crowd at Sanctuary quite druggy?

All the crowds were druggy. Drugs and alcohol. Speed the drug of choice, LSD second, downers – Tuinal, Seconal – third. There were these Lotusites, god they make you do things; extraordinary pills. Slim, oblong, purple pills.

Musically, what was Sanctuary about?

Originally, it was like Haven, but it became more black.

Incorporating some of the early funk you mentioned earlier?

Yeah. We still played some rock’n’roll there. I can remember doing ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough’ at Sanctuary. Drag shows with Princess doing Diana Ross. That was later on, when it became a juice bar, after it lost its license. When Shelley got murdered. They shot one of the quasi-owners. They were the owners, but they were also involved with the…

Mob?

Yeah. He got shot, I guess, because he was holding back money or something. Then it was fuck you, you’re dead.

And that’s when they lost the license?

They lost the license because he was murdered on the premises.

Oh shit. Pretty scary.

Very scary. I was at Tambourine one night when one of the bouncers got shot and they lay him across my feet. I used to have a booth at Tambourine which was elevated slightly. They laid him across my feet with his legs dangling on the floor. I put on James Brown Live At The Apollo, collected my records and left. Never worked there any more. We were living in a very… Cocaine had just started getting fashionable then, and cocaine is a terrible ego drug. I hate cocaine. I only did cocaine twice in my life and each time I hated what it did to me. I highly opposed it whenever I saw people doing it. I used to turn people on to LSD when I saw them doing coke. Straighten them out, you know. Have some of this!

Tamburlaine was where it all started to come to the forefront. At Tamburlaine it became popular for the intelligentsia to go to clubs. They weren’t going to Sanctuary or Haven, these were still very underground things. At Tamburlaine, because it was an east side location, it wasn’t a very big place – 300 capacity; 2,000 in Sanctuary. You had people like Peter Max, Truman Capote, Jackie Kennedy, Andy Warhol, Keith Moon. Rock’n’rollers started to come. It was the precursor to what Studio 54 became, but on a smaller scale. People still talk about Tamburlaine. I think it was the high point of my career as a disc jockey.

“ You had politics, you had funk, you had love. You had all these different subject matters to go through. I’d also try to be intelligent, I’d try to be sophisticated. But it was all about the music. ”

What kind of stuff were you playing?

Anything that people could dance to.

Which was?

Everything. It didn’t matter to me what my sources were. In fact, I had rock’n’roll records which I thought were amazing. ‘Rock The Boat’, that was a good record, but it was considered a bubblegum record. I also had a bit of an immature streak in me; still do. So my music was always youthful. We’d play ‘Looking For A Brand New Game’ by The Eight Minutes or ‘Streetdance’ by Fatback Band. I was a freak and a hippie, but I was also a radical. So I’d play these you know. I used to try to tell stories, that was my gig. I used to try and talk with the music. It changed from one story to another: I love you; I need you; you’re hurting me; I’m going to leave; But I want you back again. Then it would be: The Government is going to kill us!

Explain how you would tell a political story?

‘Law Of The Land’ by the Temptations is extremely political. ‘Papa Was A Rolling Stone’ is actually a political record. Jesus, ‘Sympathy For The Devil’ is a political record. But you were also trying to create an atmosphere with the music, too. ‘Black Skinned, Blue Eyed Boys’ by the Equals. That was extremely political. You had politics, you had funk, you had love. You had all these different subject matters to go through. I’d also try to be intelligent, I’d try to be sophisticated. But it was all about the music.

When I stopped playing records in the mid-’80s, it bored me, because I found that people were paying so much attention to the mix that they weren’t paying attention to the music. Some of these guys had these books with beats-per-minute and they’d match the songs with the bpm without figuring out that these two records had nothing to say together. Not a shred of a link apart from a tempo. They’d speed up and slow down records which we never did. We always tried to play them at the speed they were recorded. If you wanted to get fast, you played an uptempo record.

How did you come across David Mancuso?

David met me at… I guess it was at Tamburlaine or Tambourine. He introduced himself to me and gave me one of his cards and said, ‘I have parties, I love your club, why don’t you come down one night.’ I went there on my own one night and I walked into a whole other world. I walked into a world of unbelievable sound. Tremendous beauty. Just special as can be. There was nothing like the Loft. The Loft was a small little place. But it was just unbelievable. The appearance of it: it had this mirrored ball, when we didn’t have them. The whole lighting thing was much more theatre than the clubs were. The clubs were a whole lot of blinking and flashing.

That’s what Terry Noel told me.

Well, Terry was really the very first of all of them. Terry’s the guy that Francis got it from. Anyway going back to the Loft… I went to this place and it’s only black people. It wasn’t mixed at all, mostly all-black. Maybe six or seven white people out of total of 200. It used to go on to 7 am; that’s when the party stopped. The law in New York was bars could stay open till 4 am, every night except Saturday, when they had to close at 3 am. So at 3 am we’d rush down to the Loft. Ultimately, from there I took Nicky Siano and a bunch of other people. If the Loft became famous it’s because of the people I brought there. The way he operated the place was always the same. You had to have an invitation or be invited by a guest. But then people started wanting cards, so he expanded into the next loft.

What do you think separated him from the others?

David took not only the music, he knew the sonics of the records. So he’d not only match music, he’d match sonics. Because of his very sophisticated sound system. He had a really great home hi-fi, the ultimate home hi-fi: huge. But he wasn’t mixing when I met him. He had two turntables, but when one was stopping the other was starting. He’ll tell you. He did mix eventually, for a lot of years. The most popular years of the Loft where when he mixed. I said to him, you should never let the music stop and he took my advice. He had a cueing system, but he mixed like we were mixing years ago. I could always work on his hi-fi because I didn’t need to have the earphones. We got very friendly. David and I are soul brothers.

Do you think the Loft has been the most influential club then?

I think the Loft has been – absolutely and completely – the most influential club ever to see the light of day. Larry Levan, Nicky Siano, Richard Long, all these people basically wanted to duplicate what the Loft was doing, but they didn’t realise that they weren’t David. They were too stupid and to egotistical to realise that the Loft was David Mancuso playing the records, and David Mancuso creating an atmosphere. His whole head, his sophistication, worldliness, they just didn’t have it.

What did you do after the Tamburlaine?

I went to a place called Tambourine. From there, I went to Canada for a few months in 1972 because the same person who ran Tamburlaine and Tambourine ran a place called the Ginza, but I didn’t wanna work for him any more. He slapped me around. Strong-arm tactics. So I thought fuck this, and I went away. I was never attached to money or anything but playing records. I went to Montreal and worked in a place there called the Limelight, which became a huge club. Owned by George Cucuzzella, who now runs Unidisc. I walked into the club and some guys recognised me – they’d been down to Le Jardin or somewhere – and they asked me whether I wanted to work there. I can remember bringing them ‘The Love I Lost’ which they’d never heard before. They gave me ‘The Mexican’ by Babe Ruth. I brought that back here. Rob Ouimet gave it to me. I worked with him in a place called Love on Route D. I was Rob’s alternate. That was the mid-seventies, then I went back to Le Jardin. The Loft. We started the Record Pool.

David’s?

David and I, you mean. Let’s get the chronology straight. Judy Weinstein had nothing to do with the origination of the record pool. She didn’t come until about a year-and-a-half later. I’ve got the incorporation papers at home. I basically organised it. David put up the Loft as a space to organise it. I got the people together. Michael Cappello and I would go to the record companies trying to get promotional records. Bobby DJ’s the one who wised us up to that. Bobby was the first person I know to get promotional records. Bobby was very clever. Clever about the record business. So I was pretty well-known as a DJ; Michael, too. We were both at Le Jardin, because I replaced Bobby DJ at Le Jardin. David and I started the Record Pool. Please get that straight.

I was already gone by then. Twenty years later it’s still running and still pretty influential. David and I had had a bit of a disagreement. Judy came about long after I’d gone. We were such radicals! We thought we were Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin. The reason pools came about… Tony Serafino who used to work for Kudu Records which was part of Creed Taylor’s CRT had this record, ‘What A Difference A Day Makes’ by Esther Phillips. He wouldn’t give me a copy of a test pressing, because he said I wasn’t big enough. That outraged my friends. Certain companies would set up these times when you could pick up your records and these times were not conducive to the way we ran our lives. We were out till six in the morning, we didn’t wanna be going and picking records up at 11. There was this big meeting at Hollywood, Sharon Haywood ran it, which degenerated into this big screaming match. And in the middle of it, David turned round and said, Why don’t we start a record pool?’ We chatted amongst ourselves and I stood up and invited everybody down to the Loft. This was all the DJs.

Who?

Everybody. Richie Kaczor, Joey Palmentieri, Nicky Siano. I said it was pointless arguing here. We needed to get our act together. Suddenly we were standing up for ourselves. And we had this DJ meeting and we wrote this declaration of intent. I still think they’re a good idea, although record companies were supposed to contribute money to keep the pool going, but then what happens is that all turned around and they start asking for dues.

How did you get involved in production?

Through DC LaRue. I was working at Le Jardin and DC LaRue came in. I was the hot DJ at the time. Anyway, DC invited me into the studio when he was doing Cathedrals. The tempo of Cathedrals, and the conga track are my doing with Aram Schefrin. I got a credit on the second album, but I should’ve got one on Cathedrals. But I loved it. Then I got a job working at Pyramid Records, which was part of Roulette, which released Cathedrals.

Was Morris Levy still there?

Morris Levy was still the owner. They gave me a job doing promotion. Walter Gibbons had started doing these wonderful mixes. I worked for Roulette for a while. I started being DC LaRue’s buddy.

What was Morris Levy like?

He was a gentleman.

Because he’s had a bad rap hasn’t he?

He was a nice guy. He gave a lot of people breaks when they didn’t stand a chance. I’m sure he did some bad things as well, but I had no privy to that. So we had Whirlwind on Roulette. Roy B was the in-house guy, and I did promotions. I was approached to do a mix by H&O Records. They wanted me to do promotion for them and do a mix of a Sandy Mercer record. So I asked Walter Gibbons to go along. I played him the track. I like to collaborate. I wanted to work with someone I admire. So I asked Walter. We worked on this Sandy Mercer record, ‘You Are My Love’ and ‘Play With Me’ which was an even better record, but no-one ever got on it. Then I met Corey Robbins at one of these disco conventions. He was cute. He was working at MCA Publishing. Anyway, he invited me to work with this guy, Joe, who did Gary’s Gang.

Eric Matthew?

Yeah, except his name isn’t Eric Matthew, it’s Joe Tucci. Italian guy, with a studio in his garage in Queens. So I’m driving out there one night, and in the car this ‘love dancing’ thing comes into my head. You know, ‘Can you see the expression on my face?’ So I go to everyone, I’m supposed to be working on something else and I say, ‘I got this great idea, let’s do this.’

And he’s like, ‘Love dancing? What you talking about, it’s bullshit.’

Couple of months later, there’s this record by Gary’s Gang called ‘Let’s Lovedance Tonight’ produced by Eric Matthew. So I told Arthur Russell who I’d met at the Gallery. I told Arthur this story. A couple of nights later, Arthur comes back and says, ‘We’ve written a song.’

So we wrote some more words to it, and there’s a whole other part, another verse, that you won’t have heard. So one night at the Loft, there’s this back room we used, and Arthur brings his guitar and plays these songs. I said, ‘Look I can get money for this.’

So Mel Cheren [of West End Records] gave us money. He gave us $10,000, and then he gave us another. We spent $20,000. We did 14 reels of two-inch tape. We made a two record set. I said to him we were working on the equivalent of the White Album. It was all with really fine musicians. David Van Tieghem was on those tapes. Peter Gordon, the sax player. The four Ingram brothers, who I found.

“ Even before singing, there was dancing, just moving your body to rhythms. It’s one of the closest things to God. The whole experience was almost religious, we used to feel that way. ”

Who sang the vocals?

Three people from the Loft that I picked off the dancefloor. Robert Green, Melvina Woods, Leon McElroy. In one night we laid down ‘Is It All Over My Face’, ‘The Only Usefulness’, ‘Dawn Sunny’, and ‘No Heart Free’. Then we cut ‘I Wanna Tell You Today’, ‘The Only Usefulness’ and a couple of others. I was supposed to be a partner in Sleeping Bag Records. We met Will Socolov at the Loft. His dad was a lawyer. That’s later on. Arthur went along with him, I didn’t like Will’s dad. Arthur, who was constantly the starving artist, went wherever the money was. And because we had such a poor relationship with Mel Cheren…

Why?

Because he never paid us! We never had a royalty statement from West End Records, and that record’s been selling all over the world. Whatever. He keeps promising that he’ll give me my tapes back. Then he was going to make us partners in the new West End, me, Kent Nix and all these guys that he fucked over all of these years. He’s got ‘Love Dancing Part 2’ and ‘Pop Your Funk’. Actually, ‘Go Bang’ and all those sessions are the Loose Joints band. That’s why Loose Joints is so enduring though, because that shit’s all live. It was made like jazz. It’s some of the great dance music of all time. It was cut in the studio with good musicians; it wasn’t structured, it wasn’t planned. I wanted to be John Hammond, which is another reason I sought out Arthur, because Arthur was recorded by John Hammond.

CBS’s John Hammond [legendary A&R man]

Yeah. John loved him, I’ve got a couple of reel-to-reel tapes with John talking to Arthur and everything. Arthur taught Allen Ginsberg how to play guitar. And Allen was a friend of John Hammond. He was playing with Ernie Brooks of the Modern Lovers, all those guys. Arthur used to think David Byrne stole his style from him. Arthur played on Laurie Anderson records, Philip Glass. He’s been the greatest thing I’ve known in my life. Even more so than the Loft. He had this energy and the beauty of his music: the strength, the tenderness, the visuals. He was an abstract painter, really.

What do you think the legacy is that you’ve left as a DJ?

I wrote this thing in the early ’70s for [disco fanzine] Mastermix that basically said that discotheques were going to become the temples of the ’80s. They’ll replace religion. You stay at the party all night; and that’s how you get your religious training: from the spiritual aspects of music. The spiritual aspect of music was very important to us. ‘What’s Going On’ [by Marvin Gaye], that was political. So much politics in music, and we were very committed to it. We knew that some people were just coming up and they were getting their education from what we were doing. That they weren’t going to church, they weren’t going to a temple. They were learning from us. All of us thought that dancing was the first form of expression. Even before singing, there was dancing, just moving your body to rhythms. And then we found our voice. It’s one of the closest things to God. There was never a fight at the Loft, or any club I played in. The whole experience was almost religious, we used to feel that way.

© DJhistory.com

STEVE D’ACQUISTO SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

PHILLLY CREAM – Motown Review (producer)

LOOSE JOINTS – Is It All Over Your Face? (producer)

LOOSE JOINTS – Pop Your Funk (producer)

LOOSE JOINTS – Tell You Today (producer)

ARTHUR RUSSELL – In The Light Of A Miracle (producer)

BILLY NICHOLLS – Give Your Body Up To The Music (producer)

SANDY MERCER – Play With Me (remixer)

DEPT. OF SUNSHINE – Rude Boys (producer)

DC LARUE – Cathedrals (uncredited production)

RECOMMENDED LISTENING

VARIOUS – Original Soundtrack from the documentary ‘Gay Sex In The ’70s’ (CD only)

VARIOUS – David Mancuso Presents The Loft if all else fails