Grandmaster Flash

Scientist of the mix

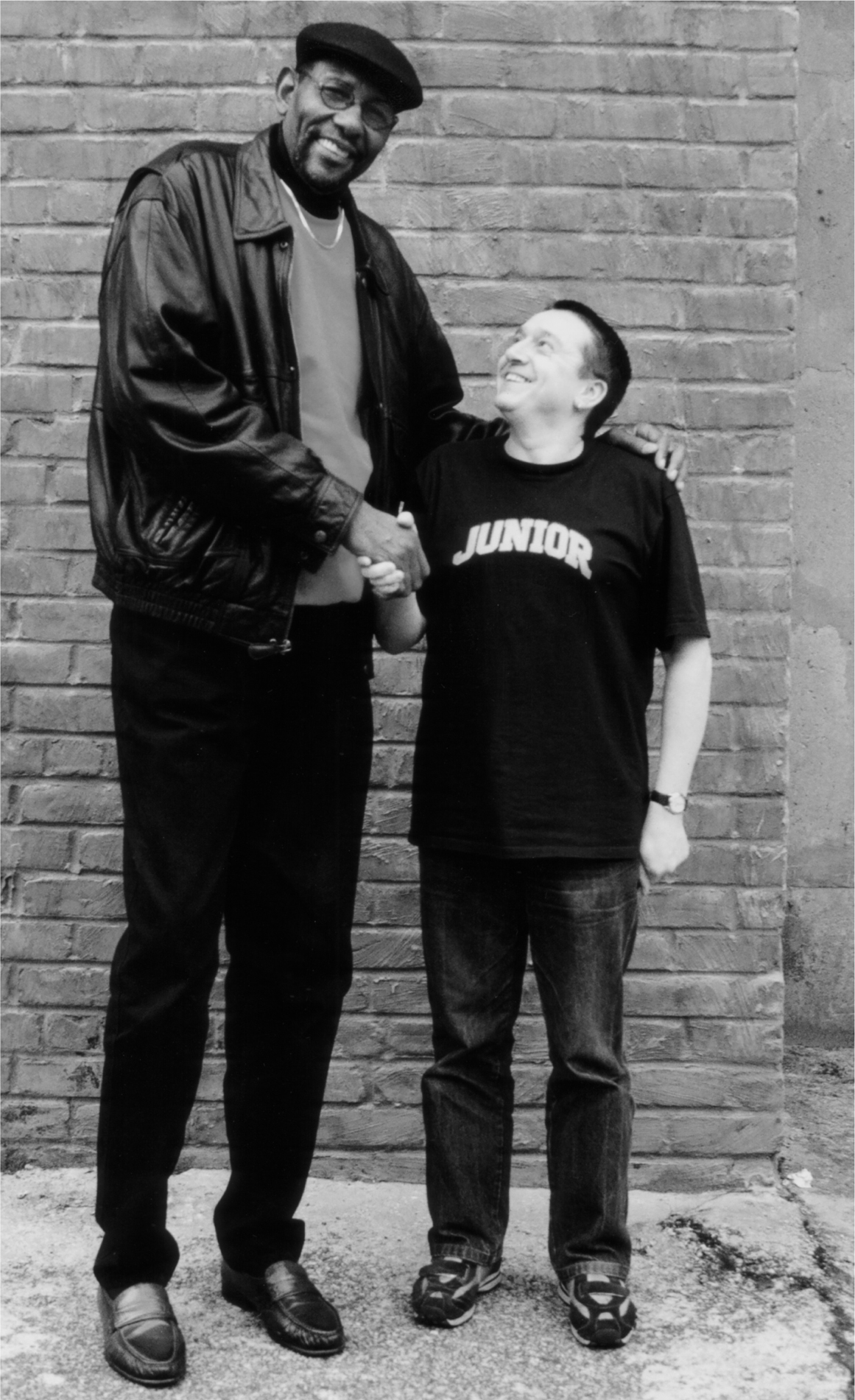

Interviewed by Frank in Long Island, October 10, 1998

Flash made hip hop possible. He took Kool Herc’s idea of playing a string of breaks and turned it from an explosive but haphazard party trick into a precise and astonishing DJ technique. In the process he revolutionised DJing because he showed how a DJ could use records to make new records. So as well as laying the foundations of a world-sweeping genre, he shattered the notions of what it is to be a musician and what it is to make original music.

The task was clear to him: work out a way of playing just the funkiest few bars from a record, then repeat that little chunk, and repeat it, and repeat it, all the time keeping the beat. In other words, manually sample a section of music and loop it into an unshakeable backing rhythm, the perfect soundbed for breakdancers to go wild to, or for rappers to rhyme over.

What makes Flash’s achievement even more astonishing is that it was no accident. He knew what he wanted to achieve without having any idea if it was possible, and then locked himself away like a scientist experimenting with potential solutions. With his cautious unemotional delivery, you can’t deny there’s a strong element of scientist in Flash. His resulting Quick Mix technique works like this: take two copies of the same record and stick a marker on each so you can see where the break starts. While one’s playing you’re rewinding the other one. Now cut from one record to the other using the mark to start them in exactly the right place, bang on the start of the beat. Practise every waking moment for about a year and you’ll have it nailed.

These days the turntablists have made it a martial art, slicing vinyl into ever tinier slivers and cutting Flash’s speed into tenths. But what they rarely have is expression. Hear Flash and it’s all about poise and pause, as he uses the cleverest slips of time and rhythm to give everything life and bounce.

“If I take the most climactic part of these records and string ’em together, on time, back to back to back…”

You got into music by sneaking records from your dad’s collection?

Yeah, that’s probably where it all started. I have to say I was pretty fortunate. My father was into primarily jazz, like Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, Miles Davis, Stan Kenton, people like that. One of my sisters was into the Latin thing: Tito Puente, Eddie Palmieri, Joe Cuba. Then I had a sister who was into the Motown sound, Jackson 5, Sly and the Family Stone, Martha and the Vandellas, Supremes. So I been pretty fortunate to grow up in a household where I heard all this. Most of my stealing came from my father’s collection. But I would also go steal my sisters’ records. And I was mostly in my room being a scientist, but on the times when I did date, I would date women whose mother, or brother, had records in their house.

So there was an ulterior motive.

Yeah, there was always a motive. If I met a person, if I met a female, in a club or whatever, and I went to meet up and go to her house, and meet her people, I’d look around. Or I’d enquire, ‘’Scuse me do you have any records?’ ‘Oh these old things? I been trying to get rid of them for years.’ And they’d open the closet and it’d be a goldmine in there, and I’d be, ‘OK this person has to be my girlfriend for a minute.’

When did you start buying records?

I started buying records when I started getting my head knocked off by my father. Because he was getting pissed off that I would take his records while he was at work. And my sisters would beef about me taking their records. If I had a girlfriend and she found out what I was doing she’d cut me off. I thought, screw this, I’m gonna buy my own records.

At this time I was going to a school that catered to electronics: Samuel Gompers Vocational and Technical High School. Now in school we were taught what mono was and what stereo was. I think the first record that I bought was this Barry White record: ‘I’m Gonna Love You Just A Little Bit More’. And what was interesting about it was I really got to hear – like we learned on the blackboard – what stereo was, and to hear how the cellos were in the left speaker, and the drums up in the middle, and the guitars was on the right. I was like: this is some shit.

That’s what propelled me to get deeper into electronics. And start getting in my sister’s room and tearing up her radio and finding out how it worked and why. And going into the backyards and looking for electronics stuff, and looking for burned out cars, and looking for capacitors and resistors.

Where were you growing up?

South Bronx. 163rd and Fox, on Fox street.

What made you want to be a DJ?

I was gonna be a breakdancer, right. But when I tried to learn it I did some moves and landed on my back and hurt it a whole lot. I tried the breakdancing thing; I was kinda wack at that.

But when I see Mr Clive Cambell, Kool Herc, sit up on his podium, heavily guarded, and all these people around enjoying themselves, from five years old to age 50, in one park, for a certain amount of hours, I said, ‘I want to do that, I wanna be that, I wanna do that.’ So with my electronic knowledge, and my ability to take what was considered junk and sort of jury-rig it together, I started to put together some sort of makeshift sound system. And it was a piece of shit, but it was mines.

At the time Herc had this pair of Shure Vocal Master columns, and these two black bass bottoms. He was always up high on a platform so you couldn’t see what he was playing. His music, some of it my sisters had in their collection, some of it I never heard before. But it had such a great feel to it.

Was he the first DJ you saw doing block parties?

He was the first, and what intrigued me about Herc was, he was playing the music that I loved, and he was playing duplicate copies of a record, he was repeating these sections, but I noticed the crowd: if they were into a record they would have to wait until he mixed it, because it was never on time. And I didn’t understand what he was doing, at the point, because I could see the audience in unison, then in disarray, then in unison, then in disarray. I said, ‘I like what he’s playing but he’s not playing it right.’

So it was more his music than his technique?

I didn’t find the way he played exciting. It was what he was playing. The music of the time was disco: like Trammps, Donna Summer, the Gibbs brothers. Herc didn’t play that kind of music, he played the songs that weren’t considered hits. The obscure records. I found that quite exciting.

What was he playing?

What was I hearing? Like ‘Shack Up’ by Banbarra. He’d play [James Brown] ‘Funky Drummer’, or ‘The Mexican’ [by Babe Ruth], a certain section, but you could see the crowd: unison, disarray, unison, disarray, unison, disarray. So the thought was to not have disarray, to have as little disarray as possible. But I didn’t know how I was gonna do it.

And there was another DJ who had a big influence on you…

Yeah, Pete DJ Jones.

And he was a disco DJ?

He was a disco DJ. What I liked about his style is that he kept the music continuous. He didn’t take out a certain section of the record or continuously go back and forth, but I just liked the way he just kept everything going. A lot of DJs at that time would just let the record play, let it end, and then bring in the next song, with no regards of beats per minute.

So he was very much programming things and building up the tempo?

Yeah.

And you became friends

When I got a chance to see his sound system, I was quite nervous. But he was very nice. Herc wouldn’t let me get close to him. But Pete DJ Jones and I became real good friends.

Were there other DJs who impressed you?

I had one chance one time to see a DJ by name of Flowers, Grandmaster Flowers. There was a DJ by the name of Ron Plummer. But my inspiration was Kool Herc and Pete DJ Jones.

And your masterstroke was to combine their two styles

How I created my style is watching Pete blend one record into another, versus Herc, who played, I call it the hit and miss factor. Timing wasn’t a factor with him, but the type of music he was playing I was quite interested in.

“ A lot of DJs at that time would just let the record play, let it end, and then bring in the next song, with no regards of beats per minute. ”

And Herc was already playing sections where he’d repeat breaks over and over?

He was taking a part of it, but his timing was not a factor. He would play a record that was maybe 90 beats a minute, and then he would play another one that was 110. He would play records and it would never be on time.

With the two different styles that Herc and Pete had, I sat there thinking about it, I said to myself there’s got to be a way to keep it on time, to take just a part of the record and keep it on time. That’s where that theory started. My thing was basically, to take a combination of both and create a style out of it.

I had to go into my room and figure out how can I make the music that I love the most seamless? So I would listen to records and I would notice something: wow the breaks on these records are really short. Like, either they were short or they were at the end of the song. Or it was a problem where the best part is really great, but it would go into a wack passage after. I could never allow myself to go into a wack passage or go off. So I had to create something that would allow me to pre-hear the track prior. That’s when I came up with something, I called it the peekaboo system.

This is something you got from Pete Jones.

Because I knew he had headphones, I guessed that he was hearing the track before, and that’s why he had no disarray. So what I had to do was build a peekaboo system. Peekaboo system consisted of a cueing system as we know it today, where I was able to pre-hear. With my electronic knowledge I was able to tap into the cartridges of both sides, run it through an amplifier, put a single-pole-double-throw switch up the middle and just split the two signals. In the centre position it would be off. Click it to the right and you’d hear the right turntable, two clicks to the left, this is where you’d hear the other one. I had to Krazy Glue it to the top.

You built your own cueing system from scratch?

Basically, yeah.

Once you had cueing, you locked yourself away. How long?

Two years.

From when?

Maybe early ’74.

So straight after you’d heard Herc and Pete Jones you’re like, ‘I got to figure this out.’

Yeah. I got to go away now.

And you totally stopped going out?

No. I didn’t play at all. I just stopped. Maybe for like a year or two. I basically didn’t have no childhood. No girlfriends, no basketball, no hanging out, straight to my room.

You were working as a messenger?

Yeah, I was working as a messenger at Crantex Fabrics. So between my allowance and my mother and my allotment for my clothing…

“ I had to figure out how to manually edit these records so that people wouldn’t even know that I had took a section that was maybe 15 seconds and made it five minutes. ”

By this time you had decks? What kind, pretty basic?

SL20s, Technics.

That’s the belt drive?

I would go through the backyards and rip out the turntables in the old floor-model stereos. I tried those and put ’em in wooden cases. I tried to do that. Of course they were horrible. I even tried Fisher Price, which is a toy company, they came up with this thing called a Close and Play.

That little briefcase thing?

Yeah. I tried that, and that was wack of course. But there was a club around the corner from my house called the Hunts Point Palace. And in this club that I was not able to go to because I was too young, the word on the street is that the sound system in there was incredible. They had the very best of amplifiers, very best of mixers, very best. And I was told by the thieves in my neighbourhood, ‘Yo Flash, I can get you a pair of turntables, that’s like the best in the world.’ I’m like, ‘Whatever, whatever,’ but I said, ‘Find out what they are.’ So they found out, they wrote it down and brought it to me – I’m into research! I found out that they were the Thorens TD-125Cs. Turntables around that time were around $1,000. They had the swinging weights and the gimbals on the back of tone arm.

So when I said I want them, they went and got them, and they brought them to my house. And I looked at my turntables and I looked at their turntables and I was like, okay now I can continue my science.

Did you just lock yourself in a room and just practice and practice?

Yeah. A lot of my friends… I had a best friend by the name of Truman, had a best friend by the name of Easy Mike who later became one of my boys and DJed with me. I had a best friend by the name of Gordon. And that’s how I came up with my name Flash. And these friends of mines used to come to my house and say, ‘C’mon, let’s go to the park, let’s go hang with girls.’ I’m like, ‘Naw man, I can’t do that. I’m working on something.’

I didn’t know what I was working on, didn’t have a clue. All I know is that with each obstacle there came an excitement on how to figure it out. How to get past it. How to get past it, how to get past it.

You knew what you were trying to do technically, but what was your goal in terms of the music and the crowd?

I’m watching Pete and watching Herc, when the song got to the climactic part, which was later to be called the break, I watched what the audience did: they got a little more physical. I’m like, ‘Oh, okay.’ So that was what the feeling was. If I could go right to the meat of the sandwich, if I could get right there… But timing was a factor, because a lot of these dancers were really good, they did their moves on time. Timing was really a factor.

So I said to myself: I got to be able to go to just the section of the record, just the break, and extend that. So these people that danced, they could just dance as long as they wanted. I got to find a way to do this. I had to figure out how to take these records and take these sections and manually edit them so that the person in front of me wouldn’t even know that I had took a section that was maybe 15 seconds and made it five minutes.

And I started to run into so many obstacles. The type of needle: I discovered that elliptical, which is built like a backwards ‘J’, although it sounded better, would not stay inside the groove. Conical, which is shaped more like a nail, although it didn’t sound as good as an elliptical, it would stay inside the grooves, and it would do damage to a record, but that’s part of the territory.

Then I had to figure out how to recapture the beginning of the break without picking up the needle. Because I tried doing it that way and I wasn’t very good at it. And that’s how I came up with the Clock Theory, and that’s what DJs do today, they mark a section of the record. And then you gotta just count how many revolutions went by. I called it the Clock Theory because you can put it at 12 o’clock, 1 o’clock, 2 o’clock, whatever, and all you do is count in reverse, how many times it passed, did it pass my cartridge, that’s my marking point. And that’s how many times I would bring it back, whether I would use what I call the Dog Paddle, which is spinning it back [fingers on the edge of the record], or what I call the Phone Dial Theory, where you would get it from the inner [fingers on the label of the record] and then bring it back. Once I figured that out, it was just a case of getting breaks. No matter how long…

Which records were the first that you were doing this with?

The early ones? Oh boy, there were so many… ‘Do It’ by Billy Sha-Rae, early Barry White records, because his joints had drums in the middle. Erm, one that probably stands out the most to me. It wasn’t an early one, but it was ‘Lowdown’, Boz Scaggs.

That wasn’t when you were first starting?

No that was later. But that was my standard. What else? ‘Funky Drummer’ [James Brown]. Actually ‘Funky Drummer’ was… It’s like a person who works out. Sometimes he’s using 40lbs and some days he wants to push 100lbs. ‘Funky Drummer’ was like 100lbs. But you had to really be in the mood. Because the way this record is, the drummer played for two bars, then the record would be off.

So if ‘Funky Frummer’ was a 100lbs, what was an easy one, when you wanted to do a lot of reps?

Ummm Barry White. ‘I’m Going To Love You Just A Little Bit More’. The break went forever, so you didn’t have so much rush. Another one that was pretty easy is, ‘Mardi Gras’ Bob James. ‘Pussy Footer’ [by Jackie Robinson], those were the easy ones.

What about the other hard ones.

‘Rock Steady’ [Aretha Franklin] was another one that was really a pain in the ass. That song, ’cos it went ‘rock… uh-uh-uh… steady… uh-uh-uh…’ then it went into that wackness. So you had to really be ready.

Any others in the Flash gymnasium?

Ace Spectrum did a song we called the piano song. It was like [hums a low pitched breakbeat rhythm] and that was it, then it went into some other piano wackness, and you had to get out of that real quick. You had to be in a real good frame of mind.

What was your schedule, you would just get up in the morning and do this?

I guess I would walk Caesar, my miniature doberman pinscher. I’d walk him, that was my best friend, Caesar. Walk him. Then I’d come in, that’s it. If it was a school week I would go to school and come right back. If I had to go to work I’d go to work and come right back. There wasn’t too much playtime, because whenever I would run into an obstacle it would nag me so much so I had to go back to it. So if I had to go to school, if I had to go to work I would immediately come back, because it was something undone.

You were approaching this whole thing in a really scientific way. What’s amazing is that you had this vision. You were so sure that if you worked out this new style, when you came out people would be amazed?

Yes.

How come you were so certain?

Because I seen people gathered from miles around just for one individual, playing music. And I seen what we used to call the ‘get-down part’ [the break]. I seen Herc play the get-down part of a record and see an audience lose their mind, but it was always unison, disarray, unison, disarray. And then when I seen Pete and his style I seen the people that followed him, I seen them lose their minds. So I knew that if I could just come up with the formula in between I would have something.

“ It was quiet, almost like a speaking engagement. I was quite disenchanted. I was quite sad. I cried for a couple of days. What did I do wrong? What’s going wrong? ”

And eventually you did exactly that.

I called my style Quick Mix Theory, which is taking a section of music and cutting it on time, back to back; in 30 seconds or less. And do that over and over, which has now become the style of DJing.

That’s the standard…

That’s the standard now. It’s my creation. This is my contribution to hip hop, to the DJing aspect, is to take a particular passage of music and rearrange the arrangement. Rearrange the arrangement by way of rubbing the record back and forth or cutting the record, or back-spinning the record. And that’s where cutting, which was later to be called scratching, came about.

When did you first play that way in public

After maybe a year I didn’t have the science down, but I had enough to go test. I was able to test on a audience. The first person I tried to show was my partner Disco B, but he didn’t quite understand it. Next person I tried to show was a gentleman by the name of Gene Livingstone, which was later to be called Mean Gene. We hooked up together and made a crew, a DJ thing.

What I said to myself is, if I take the most climactic part of these records and just string ’em together and play ’em on time, back to back to back, I’m going to have them totally excited. If I play the get-down part of 10 records in succession and keep em on time, I’m gonna have the audience in this total uproar. I’m gonna be the man. I’m gonna beat Kool Herc. But when I went outside, it was totally quiet.

Really?

Almost like a speaking engagement. I was quite disenchanted. I was quite sad. I… you know, I cried for a couple of days. I’m like, what did I do wrong? What’s going wrong?

What were the records that you played that time?

‘Johnny The Fox’ Thin Lizzy, Billy Squier ‘Big Beat’, ‘I Can’t Stop’ John Davis and the Monster Orchestra, ‘Disco Flight ’78’, and I was on time with these things.

Were you playing a set of records first to warm them up?

No I went straight in. Playing one behind another.

So maybe they were just shell-shocked.

Maybe. They just didn’t dance. And that amazed me, and it saddened me.

How did you win them over?

At first I tried to talk – wack! wack! wack! wack! wack! Once I knew I was wack, I couldn’t do that at the same time. Cut, and talk. Too wack.

That’s what Herc would do.

But if I did it the break would go into the wack part.

“ ‘Flash is on the beatbox!’ The first time we did it, we didn’t get screams and yells; it was ‘Oh shit! Flash got this new toy. Flash is making music – drum beats – with no turntable.’ ”

So you got other people to rhyme for you instead?

I will put a microphone on the other side of the table and see if anyone could vocalise to this rearrangement of an arrangement. And nobody could, until Keith grabbed the mic. Keith Wiggins, who was known as Cowboy. And he wasn’t technically good, like he wouldn’t go into any thesaurical, dictionarial, heavy words; he was simple. And he was more like the ringleader of a circus. So it kind of averted the attention away from me, ’cos that’s what I didn’t like. Although I was in the park physically, mentally I could go in my room because nobody’s paying me any attention. So now I could set up 290 records, back to back.

And that’s where Disco B came in, because now the problem was I can’t play and look for the record at the same time. So that’s where the pass came in. I called it the pancake factor, because its like flying pancakes. ‘Okay I’m done with this,’ bam! ‘I’ll throw you this, you throw me that, I’ll pass you this one, you slide me this onto the turntables,’ and it was me and B doing this passing thing. So physically to see it was some thing. And with Cowboy saying the things that he did, he made it credible.

And then you had Theodore

Theodore was the icing to the cake. That not only could a teenager [Flash] do it, but so could a little kid.

How did he learn?

The system was in Gene’s room, his mother’s stereo was in the living room, and it was this little kid that… Where I would repeat a record by spinning it back, and repeating, spinning it back, he would pick up the needle and just repeat it with one turntable. He would just pick it up, and go right to the beginning of the break, and it was quite amazing.

And how about scratching. Because between you and Theodore it’s a little fuzzy as to who started it and who popularised it?

Well the way I see it is, if I didn’t create the style, there wouldn’t be no style. You can only invent something one time. You can always put an extension on it. I think I’d have to say, rearranging a passage of music is mines. Which meant cutting, rubbing the record back and forth. But Theodore, he put another rhythm on it. Just like between Cash Money and DJ Jazzy Jeff, somebody put another rhythm on it, which is transforming [using the volume faders to cut up a scratch sound]. So it’s actually taking a record and moving it back and forth, that’s where it basically starts, but then it’s a matter of the rhythm and how do you work the fader.

How you want to draw the conclusion, that’s up to you, but this thing, on a whole I created on my own. There was no blueprint, no draft, it was nobody else doing it. Period. End of story. There was a little kid on the living room who I invited in against my partner’s wishes, to learn this. If I had kept that room closed, and kept it shut, he might not have learned it. I would give Theodore credit. I would rub it, I might go zuh-uh, zuh-uh. He might have went zuh-huh, uh-huh, uh-huh. So…

It’s one of those things. You’re hearing the scratch in the headphones, you’re going to think, ‘Oh that’s a good noise’.

It’s just my theory, that you can only invent the car one time. You could make a round car, a square car, a car with jets. A car with two engines…

How about the beatbox?

It’s my invention. There was a drummer that I knew. At the time it was sort of, not really a battle, I don’t use that word too much. It was basically for who had the most showmanship between Bam, Herc and Flash. Bam had the records, Herc had the sound system. My sound system was pretty cheesy, so I knew I had to constantly keep adding things and innovating just to please my audience. Because once they’d go to hear a Herc sound, then heard my sound – eurggh! It was OK.

So, there was this drummer, who lived on 149th Street and Jackson. I think his name was Dennis. He had this machine, this manually operated drum machine, a Vox percussion box. Whenever he didn’t feel like hooking up his drums in his room, he would practise on this machine. It was manually operated. You couldn’t just press a button and it played, you had to know how to play it. And he would use it for fingering. It had a bass key, a snare key, a hi-hat key, a castanet key, it had a, erm, timbale key. And I would always ask him if he ever wanted to get rid of it I would buy it off him. He sold it to me and I gave it a title: Beatbox. My flyer person at the time, my agent at that time, which was Ray Chandler, put this on the flyer: ‘GRANDMASTER FLASH INTRODUCES THE BEATBOX. MUSIC WITH NO TURNTABLES!’ As a drawing attraction.

When was that?

I think maybe ’74, ’75. Once I learnt how to play it, I stayed in my room for a month. And myself and my MCs became a routine, ‘Flash is on the beatbox!’ So the first time we did it, we didn’t get screams and yells and whatever; it was ‘Oh shit! Flash got this new toy.’ It probably got back to Bam, it probably got back to Herc: Flash is making music – drum beats – with no turntable.

Did you play records over the top?

No, what I would do is play it, play it, play it, play it, stop. DJ. So like [a little rhythm] doomm ah da-da uh-hah. Stop, zoom play in a record. So it was like I had both of them ready and I would just kinda like, while the MCs was MCin’, where you would fade the beat out for a minute, I might switch back to the turntables. Or I would fade that out and the MCs would be doing a routine and I would go back to the beatbox. It was a real high part of our performance. A real high point.

And there was a lot of competition for records, too.

Herc and Bam and me. That’s what separated us; that’s what made us the shit for a minute: who had that record, who had that real special record. Like Herc had the Incredible Bongo Band, ‘The Rock’ [‘Bongo Rock’]. Grandmaster Flash had Bob James. Bam might have the Pink Panther with a drum beat.

Amongst the three of us – matter of fact there was even one more, which was DJ Breakout, and the Funky Four, which was way, way, way uptown. We were in a mad scramble for that song that would just get ’em going. I would never forget, me and Herc… Herc wouldn’t show me ‘Bongo Rock’ for a long time. But then he wanted to know ‘Sound Of A Drum’ by Ralph McDonald. And I wouldn’t show him that.

Which were the other ones you had first?

I don’t know, My Ralph McDonald, ‘Sound Of A Drum’, which I called ‘Crackerjacks’, Bob James ‘The Bells’ [‘Take Me To The Mardi Gras’], actually I bumped into that from a friend that was a friend of mines, I got ‘Big Beat’ from DJ Breakout which was Billy Squier. I couldn’t get too much from Bam because Bam’s shit was so deep and so powerful I just didn’t know where he got it. A lot of shit I just got on my own. Or I got ‘The Mexican’ from Kool Herc.

Where did your name Grandmaster come from?

Came from a fellow that used to come to my club. Fellow by the name of Joe Kidd. Said to me you need to call yourself a Grandmaster by the way you do things on the turntables that nobody else could do. It sounded good, but I wasn’t going to do anything that didn’t mean something. Flash was my favourite cartoon. I liked things that moved fast.

When did you start being called Flash, before you started playing records?

My buddy Gordon gave me Flash. And that’s way before I started DJing. So I became Grandmaster in 1975, January 1st. Actually it was ’74 maybe. It connected with Bruce Lee which was the leading box office draw for movies at the time, and it connected to this guy that played chess, and these guys were very good at their craft. I felt I was very good at my craft. I found it fitting: Grandmaster. Flash. Grandmaster Flash. And that’s when it became Grandmaster Flash, Scientist of the Mix. And that was my tag.

How did you feel when the first records came out? For a long time people didn’t even think this was something you could put on a record.

I was asked. I was asked before anybody. And I was like, ‘Who would want to hear a record which I was spinning re-recorded, with MCing on it?’ I told these record companies, these small mom-and-pop record companies, just leave me alone. I’m not interested

What changed your mind?

I guess it wasn’t until I heard this song: ‘What you hear is not a plate I’m rapping to the beat.’

Sugarhill Gang.

Yeah.

People never heard of them.

Never heard of them. They didn’t pay no dues at all. Like if they’re not from any of the five boroughs, where are they from? One of the members was a bouncer for Kool Herc, at one of his clubs. So he was able to get a real close look at this rhyming thing.

They pretty much took all the rhymes that were going around.

Yeah basically. He was able to see Cas from the Cold Crush Brothers, he was able to hear Melle Mel, he was able to hear Coke La Rock. He was able to hear the best, do this. And he was working in a pizza shop out in Englewood [New Jersey], and he was asked to be a part of the group, and he was kind of asked can he do that stuff, and he said sure. It was somebody else’s stuff but he was able to do it. And that’s how he became part of the group.

What was your reaction when you saw that someone had made a record?

I was like, ‘Damn I coulda been there first.’ I didn’t know. I didn’t know the gun was loaded like that. Blew up. It was a huge record for them. It was okay though. ’Cos we were gonna come later. We had the talent, and they didn’t.

“ Joe Kidd said to me you need to call yourself a Grandmaster by the way you do things on the turntables that nobody else could do. ”

You did make records pretty early on. How did ‘Superrappin” come about? Was it a version of what you would play in the clubs?

It was more like our added attraction into our act. At that time [DJ] Hollywood did something to the industry, instead of taking a sound system to a building and playing from 10 till four, Hollywood would be on four flyers in one night, make four or five times the money. So eventually all of us put away our sound systems so we would do two to three parties a night. We could do this: if we went to Staten Island, then we might go to Manhattan, then we might go to the Bronx. So what we would do is our normal party thing but then we would perform ‘Superrappin” as an added bonus.

The record is…

Tyrone Thomas and the Whole Darn Family ‘Seven Minutes Of Funk’. It’s the beat that we used as a backing, and when Bobby Robinson said can you make a record…

It was made with a session band?

Yeah. It was a band.

You asked them to cover the record the way you would play it as a DJ?

Yeah we showed them what it was and they played it over. That was it. And that was our extra added bonus, to go round and do two or three extra parties. Not only were we doing what everybody else was doing, but we had a record.

How did you feel when you’re a DJ and you get offered the chance to make a record and you have very little to do with it?

Quite frankly, once I walked into this huge room and seen how it was made, I was like okay, well maybe that’s how it was done. Because I knew the end result, when they pressed it I was gonna be the one that set it off anyway. So it didn’t really threaten me. I didn’t even know better enough to really be angry. And that’s what I seen on both occasions. At Enjoy, they had a great house band, and at Sugarhill. Had a great house band so I was like okay that’s how it’s done.

I knew that eventually when it became wax I would get special versions of it that only I had, that we would perform. Live. No vocals. No nothing. Raw track. And we would do it live. And that’s what I would have. And that’s what we did. We also made a show where they would disappear for a while, go off into the wings and I would do my thing. It was a show. A show.

“ Hip hop is not perfect. That’s what makes it dope, the imperfections. It’s strategically where it’s placed that makes it hot, makes it fat. ”

Did you suggest making those early records from records instead?

I think at the time I was trying to show Sylvia how you would take it directly from the record but she wasn’t with it. And it would have been a long laborious process, because it would have been: record 30 seconds, hold the tape, then punch, then segué… It would have been a long process just to get it on tape. Especially if it was a short 15-second break and you needed five minutes, that’s like maybe 80 takes, 100 takes, 200 takes, and who was to say they were gonna be on time? She didn’t want to do that.

Because of the studio time

Yeah. Didn’t want that deal. She preferred to have it recreated by a band. And the band was excellent though. I wasn’t too mad at that.

Did you feel, ‘That’s taken my role away’?

Basically I did. I did feel that way, but at the time it was my group, my concept. I was part of the group. It was cool.

But eventually you made ‘Adventures On The Wheels Of Steel’, which is a totally different thing, because it’s actually a snapshot of you as a DJ. How did it come about?

I spoke about it with Sylvia quite a few times. And then eventually Mel and I talked to her about it, and then she agreed to take a shot with it. We came up with the compilation of records we wanted to use. You know, all the hit records of that time. And with some of the Sugarhill product. And we did it.

How did you put it together?

It took me three hours. I had to do it live. And whenever I’d mess up I would just refuse to punch. I would just go back to the beginning.

So how many takes?

It was a few. Because now it was a matter of no mess-ups allowed. Timing was critically a factor. ’Cos this was going on a record. So I dunno, 10, 15 takes to get it precise.

How many decks did you have set up?

Three. Three decks, two mixers.

Can you remember how you felt when you heard the playback?

I was scared. I didn’t think anyone was gonna get it. I thought they might understand this. DJs’ll probably love it because at that time, this style, my style of what I do on turntables was not fully saturated. People still didn’t know what I did, or knew who I was, or thought I was a rapper, or whatever. So, to put the record out, it did okay. It didn’t take too well in America, because people could not quite understand what it was I was doing. Frankie Crocker used to play it on WBLS quite a bit. So in New York I had gotten some small recognition for it. But in Europe the record was huge.

It did demand that I do it live. I’ll never forget that. Sometimes I would be so nervous that I would mess up, and I’d stop and say, ‘Can I try it one more time?’ and the crowd would say ‘Yeahh.’ Cos it was like three decks, two mixers, there was some shit to do. The precise passing of the records, everything had to be where it had to be. Records had to be off. Shit was just flying. It was cool though.

You’re very much a perfectionist.

Yeah, sometimes that hurts me.

Why do you say that?

Because hip hop is not perfect. That’s what makes it dope, the imperfections. It’s strategically where it’s placed that makes it hot, makes it fat.

What’s the thrill you get from playing to a live audience?

The adrenalin flow. I guess. The screams, the yells.

What do you think when you see these turntablist guys and they’ve taken what you started and run with it? I mean Roc Raida, someone like that?

I love it. I love it. Just to see them break it down and do some of that crazy shit. In between the beat, in between the fly’s ass. I love it, it’s fucking great. I love it.

And that’s all from your idea.

I like to remain modest about this accomplishment that I did, but there seems to be so much confusion about who started what and who did whatever. This is my contribution to this.

Without a doubt.

Nobody from old school or wherever can take this from me. It’s three years of my life that I took to do this. You see, this is what’s important to me. I don’t care who’s better, who’s worse… First! My contribution is first. Because first is forever.

© DJhistory.com

GRANDMASTER FLASH SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

GRANDMASTER FLASH & THE FURIOUS FIVE – Superrappin’ (writer)

GRANDMASTER FLASH & THE FURIOUS FIVE – Adventures On The Wheels Of Steel (architect)

GRANDMASTER FLASH – Flash To The Beat (writer)

GRANDMASTER FLASH & THE FURIOUS FIVE – It’s Nasty (writer)

GRANDMASTER FLASH & THE FURIOUS FIVE – Scorpio (writer)

GRANDMASTER FLASH & THE FURIOUS FIVE – Black Man (writer)

GRANDMASTER FLASH & THE FURIOUS FIVE – Fly Girl (remixer)

MICHAEL VINER’S INCREDIBLE BONGO BAND – Apache (remixer)

GRANDMASTER FLASH & THE FURIOUS FIVE – Gold (producer/writer/scratching)

GRANDMASTER FLASH – Larry’s Dance Theme (producer/writer)

DOOM – Shake Your Body Down (producer)

RECOMMENDED LISTENING

VARIOUS – Grandmaster Flash: Essential Mix Classic Edition (CD-only)

VARIOUS – Grandmaster Flash Presents Salsoul Jam 2000

GRANDMASTER FLASH – The Official Adventures of Grandmaster Flash