Marshall Jefferson

Leader of the jack

Interviewed by Frank in Billericay, February 22, 1999

A friend described Marshall Jefferson as someone who’s still excited that he’s not a postman any more, and sure enough, he seems constantly thrilled that he gets to do things like make music and do interviews and play records for money, bursting out with wild snickering laughter like a naughty kid after school.

As cheap electronic instruments revolutionised music-making, Marshall was one of the first in line for a synthesiser. And as Chicago dancefloors became the testing ground for home-made dance music, stripped-down to the basics, and made by clubbers instead of musicians, he became one of the city’s leading producers. With no musical training, in the space of a couple of years or so he’d made classics that had made it round the world to soundtrack Britain’s acid house revolution.

Bizarrely we meet in deepest Essex in a tiny Brooksidey close in a little country town that has played host to some of the biggest names in American dance music for the last 10 years. Pierre stays here, so does Tony Humphries and so apparently do loads more DJs from the Windy City, thanks to the fact that the house is owned by a DJ agency. It looks like your mate’s just-left-school, boys-only crash-pad. There’s a copy of Playboy on the sofa and a shelf with every single Star Trek episode on video. Serbia’s biggest DJ is upstairs in a home studio and some American guy is knocking up health juices in the kitchen.

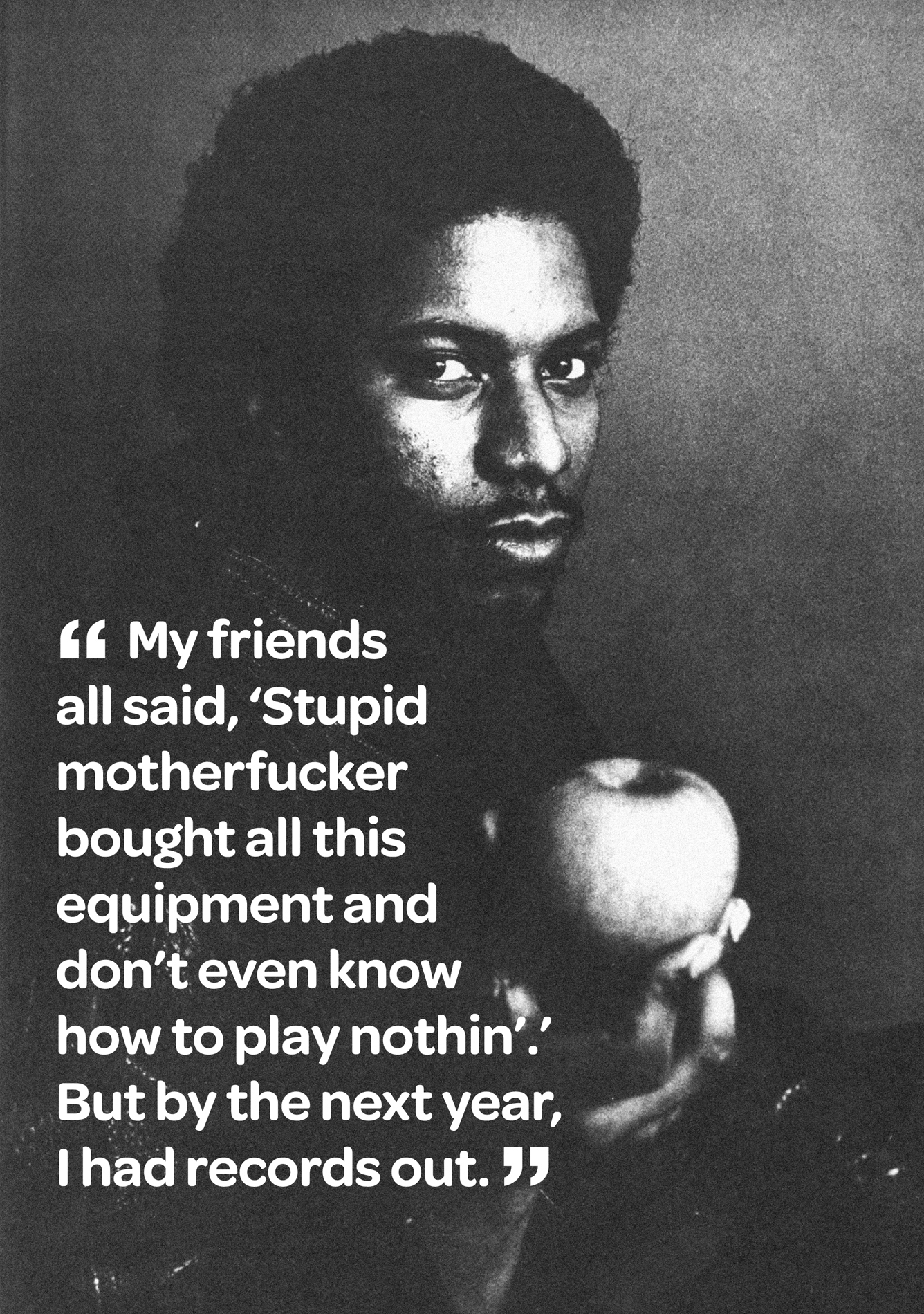

“My friends all said, ‘Stupid motherfucker bought all this equipment and don’t even know how to play nothin’.’ But by the next year, I had records out.”

One thing I can’t get is that the name house music…

…Comes from the Warehouse.

But the music that Frankie Knuckles was playing at the Warehouse at that time was pretty much straight-up disco.

Disco, yeah, yeah, yeah.

He was editing it, extending it, but it was disco. So how come the same name was then used for these tracks that everyone started making?

Okay…

How come they didn’t call it something else?

Because they ripped off old disco songs. And also, by then they would call anything that was played in that type of club, ‘house music’, right. Underground music was ‘house music’ to us. It was house music because of where it was played, not because of what it sounded like. The name house music got its name from Frankie’s club. Just like garage got its name from Larry Levan’s club, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that he was making the music. It’s like, Tony Humphries don’t make no music, right, but suppose somebody made some music and called it Ministry music. Right, boom, that’s it. So that’s the thing.

Did the scene feel very special?

Hell yeah, we would hear music that nobody else would hear… in the world!

Did people realise that?

We would walk down the street and see somebody and say [dismissively], ‘They don’t know what’s happening.’ We had that pride about our musical taste.

And people would actually say, ‘He’s house but he’s not house’?

Right.

You could tell by what people looked like?

The clothes and the styles, the same thing, you know. You could tell who had a clue and who didn’t. Or what they were listening to on the radio. If they were listening to the Gap Band they weren’t house [collapses in laughter].

What kind of things were people wearing?

It was hard to explain. You would have to ask somebody else about the fashion aspect. I was automatically house because I was making the hippest records in the city [cackles uncontrollably].

So who started house music as we know it?

Jesse Saunders is behind every thing in your interview. He did the first house record and the significance behind that, right, is, it got non-musicians into making music. Everything came from that. See, Jesse was a DJ. He was one of the top club DJs in the city. And the next step for him was to make records. Vince Lawrence talked him into it.

“ It was Jesse made everybody want to go and get a drum machine and start making records, because… Jesse’s shit wasn’t that good. ”

Making records for his own dancefloor.

Yeah, for his own dancefloor.

That was his track ‘On And On’.

Yep. I’m telling you the amount of stuff that comes from Jesse, that you can trace back to Jesse Saunders, is every single thing that’s happening now.

So what made him start making music?

He wanted some pussy!

Simple as that?

Him and Vince Lawrence, because Vince Lawrence’s dad had the record company, and Jesse Saunders was the star DJ. He was the biggest DJ in Chicago. Jesse Saunders actually put out a record. That’s what got me started in house music. That’s what got everybody started in house music.

But people were making tracks before they were making records. People were making tracks and bringing the reels straight to the DJ.

Yeah, Jamie Principle. But, the thing is, right, nobody started making music because of it. Jamie’s stuff was too good. Nobody thought they could duplicate it. Everybody thought that Jamie was somebody from Europe.

But he was pretty much the first?

Actually, Vince Lawrence was the first ’cos his dad owned the record company. And, if you listened to Vince’s first record, ‘I Like To Do It In Fast Cars’, it sounds like house music, but at the time it wasn’t considered house music.

Why not?

Nobody paid attention to it. He wasn’t a star DJ. He just put out records.

So Vince made some records that got ignored, and then Jamie Principle started making tracks and giving them to Frankie Knuckles to play?

Right.

And was that what made everyone suddenly want to go and get a drum machine?

No – it was Jesse made everybody want to go and get a drum machine and start making records, because… Jesse’s shit wasn’t that good. You know what I’m saying? It made it more accessible. When Jamie’s stuff was played in the clubs, everybody was like ‘Fuck that’s too good! I can’t do anything like that.’ But when Jesse did it everybody says ‘Fuck! I could do better than that!’ When Jesse did his stuff everybody started making music. You see?

Exactly, you feel ‘Well I could have a go.’

That’s what got me involved. That’s what got everybody involved. You got all these DJs starting to make records.

If it wasn’t great music, what was its power to inspire?

Okay, supposing there were no porno movies and then people started making porno movies, and they were all the rage, and you knew the main porn star, right, and your dick was twice as big as his, and he turned out to be a millionaire. Now wouldn’t you consider to give it a shot? Hell, you know what I’m saying. That’s what’s inspiring. Somebody make it big…

…but not be that great.

Yeah. You see what I’m saying?

Exactly, exactly.

And that’s how it was. That’s what inspired everybody. It gave us hope, man. When Jamie was doing it, nobody thought of making a record. His shit was too good. It’s like seeing John Holmes in a porno movie. You know you can’t do better than him. But if porno movies were just starting, and you see a guy with a three inch peter, and all the women are swooning all over him and he’s a fucking millionaire, you would seriously consider it, wouldn’t you?

When Jesse made his first tracks, how was he getting them out there?

Man, Vince Lawrence and Jesse were totally driven by pussy. Now I’m gonna tell you something… [stops his thought] No I’d better not say it.

Jesse’s stuff started playing on regular radio in Chicago. He was bigger than Prince in Chicago, man! And next to Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, it would sound like bullshit. It would sound like tin cans, man. But, everybody knew Jesse, so it was popular shit. And by the time he finally did ‘Real Love’, which was one fifth the quality necessary to make the radio – everything else was like one twentieth; that shit came out, it was huge! But none of it left the city. Because Jesse didn’t leave the city. If Jesse would have left the city, or if the States had a national radio station, and a female programmer on there… [Laughs fit to bust]

He’d have been off the hook!

Yeah, man, oh it was so fucking exciting, to see, behind the scenes. To see all this shit coming together, and Jesse was, he was the king, man. But nobody knows about Jesse, That’s the thing.

Why not? He’s in LA, isn’t he.

Well see, this is the thing right: everybody started making better house music.

Who was next out of the gate?

Me, Farley ‘Jackmaster’ Funk, Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley, Larry Heard and Adonis. When us five came out, all at the same time, house music left Chicago. And that’s when Jesse stopped doing house music. For some reason. Well the reason was… he got a major label deal. So he was, ‘Aw fuck house music. Been there, done that, I’m gonna start doin some R&B now.’ And when all this shit started happening, when everybody started saying ‘HOUSE MUSIC, HOUSE MUSIC, HOUSE MUSIC’, there was no fuckin’ Jesse Saunders.

He’d already left town?

He’d already left town. He was going for the big shit.

He missed all the fun

See that’s the thing. Everybody’s gonna tell you what they did, and all that shit, but nobody woulda got started without Jesse. Nobody. Jesse Saunders and Vince Lawrence…

Vince’s father owned a record company.

Yeah, Mitchbal records. Mitch is still around.

Wasn’t that an old soul label?

I don’t know what it was but he put out the first house records.

So that was even before Jesse had stuff on vinyl.

Yeah.

How come Vince didn’t get any recognition?

Nobody really knew Vince, ’cos Vince didn’t sing. Jesse sang on his shit. And Jesse Saunders was a star DJ. Jesse wouldn’t have made records if it wasn’t for Vince, you see because Vince’s dad owned the record label right. Vince, went to Jesse and said ‘Hey man we could get a lot of pussy, man, putting out records. We could be fuckin’ superstars.’

They were pushing each other forwards.

Well, it was like, Vince pushed, man. Vince was the pusher. Jesse, said okay. Jesse was driven, but nobody was driven like Vince. ’Cos if you meet Vince, he ain’t gonna get laid unless he got an edge.

So what about your clubbing days? You went to the Music Box right?

Yeah. I wasn’t even into dance music before I went to the Music Box. I was into rock’n’roll. I was a postman. We used to get drunk and stoned after work every day. We would call it a different holiday. ‘It’s… hmmm… Kiss the Nuns Day’, woo-hoo! And we would get drunk and listen to rock’n’roll. We were like ‘Disco Sucks!’ and all that. I hated dance music ’cos I couldn’t dance. The only reason I got into dance music was there was this girl at work, she took me to the Music Box, and I thought dance music was kind of wimpy, until I heard it at Music Box volume.

What was the difference?

The volume, man. The way Ron Hardy played. I had never heard music at that volume since. It was really amazing. And in like 15 years I have not heard a single club that even came close to that volume, and the reason being, there would be loads of lawsuits from damaging your hearing. Because the Music Box was so loud anywhere in the club, not just on the dancefloor, anywhere in the club, the bass would physically move you.

How big was it?

I guess, maximum you could fit up in there would be about 750.

So who took you there the first time?

This girl, her name was Lynn, she’s really religious now, but she was a stripper back then. Great body, right, and she liked me, and stuff. I never jumped on her, ’cos she was working at the Post Office right next to me every day. That was a little too close. I wanted to be a bachelor, I wanted to like spread myself around. Anyway, she took me to the Music Box. I just wanted to go ’cos I wanted to see her body in action. She was wild, you know. She would talk about all the stuff she did, it was really wild stuff, so I wanted to go to the wild club she was going to.

What was the crowd like?

It was mostly gays, and you know man, I got in there, I never heard any music like this, I was like, fuck! Damn! This is brilliant, great, and that’s when I got into dance music.

You found religion.

Yep.

Did it feel like that?

Yeah, man. One night I got converted to dance music, by Ron Hardy.

Did a lot of people feel that way? You get the impression that it was church for people.

Yeah.

Can you remember the songs he was playing that night?

‘Let No Man Put Asunder’ [by First Choice], ‘I’m Here Again’ by Thelma Houston, ‘I Can’t Turn Around’ by Isaac Hayes. All of those.

“ I hated dance music. The only reason I got into it was this girl at work, she took me to the Music Box. I just wanted to go ’cos I wanted to see her body in action. ”

How would you describe Ron Hardy’s style?

Well, I’ll tell you sir. There was two distinctly different styles. Frankie played more disco. He didn’t get into the new wavey stuff like Ron Hardy did.

What sort of things?

Well, you know stuff like, ‘It’s My Life’ by Talk Talk, the ABC stuff, Eurythmics, all that shit, ‘Frequency 7’ by Visage. Frankie wouldn’t play none of that shit. Frankie would play like more straight-up disco, the black disco stuff. But Ron hardy would play it all, man, at really high speeds.

Really?

It was rockin’, man. And Hardy was busier with the records, too. He would fuck with the EQ more. Frankie would just mess with the bass occasionally; Hardy would mess with every fuckin’ thing.

And he would extend everything for ages?

Both of them would extend everything for ages, to tell you the absolute truth. But I would watch Hardy sometimes, editing songs, man, and he would do it with just a cassette player, he would play the record, ssst, pause and then whmp play it again, the same part and pause whmm then do it again.

He would make loops with a cassette deck?

Yeah. Right on a cassette deck. Then when the party come, he would play the cassettes.

Was he playing a section of disco and a section of new wave, or mixing it all together?

Mixing it all together. Hardy… did every single drug known to man. How the fuck you gonna programme that? He didn’t give a fuck about programming.

He was just for the moment.

Yeah. And when I saw Larry Levan later, I wasn’t impressed, because I’d already seen Ron Hardy. Same type of DJ, but Larry Levan passed out while he was playing. Ron Hardy never passed out while he was playing. As high as he got, he never passed out, ’cos he was so pumped up.

Right.

Larry Levan would pass out, fall asleep on the decks, you know all of a sudden you hear a [needle scratch noise] somebody grab him, move him out of the way, ‘okay I’ll take over,’ Larry Levan would have on nights, where…

…Where it worked.

Yeah. But he played the records at their proper speeds.

So how fast was Ron Hardy playing them?

Well… Shit man, Hardy would do shit plus six, plus eight, you know, fast as he could play it.

Must have been a crazy atmosphere in there.

Yeah, the energy man, the energy. Since Larry Levan played everything at the proper speed, there’s no way he could duplicate Ron Hardy’s energy.

After Jesse Saunders inspired you, how quickly did you get into making tracks?

I would say after Jesse’s first record came out, in about two months, I bought equipment. In two months I started making tracks. I was working at the Post Office; I had a good job. You should see how the sales people in America treat people from the Post Office, because they know it’s the closest thing to impossible to get fired from. So I was able to buy the equipment. We went to a music store, me and a friend of mine who played guitar, and this guy at the music store showed us a sequencer. Told me, with this thing you can play keyboards like a real keyboard player. And my friend was like, ‘That’s bullshit, you gotta take lessons.’ And I was like ‘No, man, I believe him. I’m gonna buy it.’ He said, ‘No man, don’t buy that shit,’ ’cos it cost like $3,000. But since I was working at the Post Office I got instant credit. The only reason I bought it was I thought that must be what Jesse Saunders must be using. I didn’t know he had a keyboard player playing all his shit.

“ Hardy never waited for the record, you gave it to him on cassette. ”

So I said, man I want to be like Jesse Saunders, ‘Okay, I’ll take this sequencer’. He said ‘Wait a minute, you don’t want this sequencer and not have a keyboard to play, do you?’ ‘Oh yeah, you’re right.’ So I bought the keyboard too. And he said, ‘Hey, you don’t want to have this sequencer and this keyboard and not have a drum machine?’ I said ‘Oh yeah you’re right.’ He said, ‘You don’t want to have this sequencer and this keyboard and this drum machine and not have something to hear it all on, do you?’ I said, ‘Yeah you’re right.’ So I bought this mixer. ‘You don’t want to have this sequencer and keyboard and drum machine and mixer and not have something to record it all on, do you?’ So I bought this recorder, right. And he said, ‘You want to have a good monitor system, and you want to have a second keyboard, and this bassline, this 303. I was like yeah, yeah, yeah. Well I ended up spending about nine grand.

What did you end up with?

A JX-8P keyboard, which I still have. A TB-303, which I think I got for under a hundred dollars; sold it for a thousand to Bam Bam. Sucker! A Korg EX-8000 module, a Roland 707 drum machine, a Roland 909 drum machine, Roland 808 drum machine…

The whole works.

Oh man! I got a Tascam 4-track recorder. I got a whole bunch of shit.

So you took all these goodies home. How long did it take you to start making tracks?

Er, two days. Because that night my friends all gave me grief, they came over and laughed at me, said, ‘Stupid motherfucker bought all this shit and don’t even know how to play nothin’.’ But by the next year, I had records out. ‘Move Your Body’ came out and all the DJs in the world when they found out about house music, they started hiring keyboard players to play like Marshall Jefferson. So there! [Uproarious laughter]

So how did you do it?

Well ‘Move Your Body’ was at 122 beats per minute, right. I must’ve recorded those keyboards at 40, 45 bpm: Dumm dum DER DER DUM bom-bom-bom. Then I speeded it up: ‘Oh Marshall’s jamming! Oh man!’ You know.

That wasn’t the first track you made?

No man. I made a rhythm tracks album. I made Sleezy D ‘I’ve Lost Control’, before that.

Which was the first one that got played in the clubs?

Sleezy D ‘I’ve Lost Control’ was huge at The Music Box, man. Yeah, man. ’Cos Hardy could relate to that. Frankie didn’t know what the fuck was going on.

He was always in control!

Yeah. You know. He didn’t know what to do about that. So he wouldn’t play it. When I did ‘Move Your Body’, he liked that. But ‘I’ve Lost Control’, you should have heard it man, they used to go ballistic when that shit came on. ‘I’ve lost control… AAAAArghhhghggghgg!’

And he played it from a reel, or did he wait for the record to come out?

Hardy never waited for the record, you gave it to him on cassette.

On just a regular cassette?

On a cassette, man. I would take the cassette down. I would put it on the DJ booth. Ron Hardy wouldn’t even see me come up there. I would just put it there and – whoo – leave. So I had this mysterious thing about me. Plus I had to stop going to the Music Box because they put me on the graveyard shift at work. So my friend Sleezy started taking the tapes to the Music Box. And of course he told everybody down there he did it. Right. So at first everybody thought Sleezy did the stuff until I got my hours changed at the Post Office.

So you didn’t even see how people were reacting to it.

No.

What was it like when you walked in and they’re playing your track?

The first time I went to the Music Box – and heard my stuff playing? ’Cos I had gone to the Music Box before, that was the inspiration for all of my music…

You were making it thinking of that crowd and that place?

Yeah. That crowd and that place, man! Every record that was coming on they were screaming! He played seven of my records in a row. Seven! And by the time the fifth one got on, it was ‘I’ve Lost Control’, and that was the biggest reaction. They ran onto the dancefloor. It was like a stampede, everybody going aaaarghhh, and I was thinking ‘Oh man. Yes!’ ‘Lost Control’ wasn’t the only song. But it was the biggest hit out of all of all the songs I did. Ron Hardy played all of them.

What were the other ones?

Shit, I don’t know man.

They never came out.

Well, they got covered. Illegally. A lot of the Chicago stuff that came out, were like remakes of other people’s tracks, or in some cases, the actual track itself.

Dubious ownership.

But you know, I didn’t care. Everybody knew I did it anyway, but Sleezy of course told everybody he was doing the tracks… ’cos he was sleazy! So when the record came out we had to call it Sleezy D, ‘I’ve Lost Control’. He was really pissed off about the D.

Why?

Cos he was just Sleezy, man. Everybody called him Sleezy. But at the last minute, guy from Trax Records, Larry Sherman, he put ‘Sleezy D’ on there because of Chip E. And Sleezy, he hated it, he said, ‘Man, I’m just Sleezy,’ he said, ‘Fuck that D.’

So you’ve got all these kids running around making tracks and giving them to the DJs to play. Did some people take them to Ron and some to Frankie?

Well, Ron was more accessible than Frankie, because Frankie had Jamie Principle.

He was a little more discerning?

It was better quality than what everybody else was bringing.

You couldn’t take him a cassette I’d imagine.

Well, he took a cassette of ‘Move Your Body’. See Jamie’s stuff was higher quality to everybody, so after that it wasn’t too much he would play, but Hardy would play everything. He wouldn’t care what kind of quality you were. If it rocked the crowd then he would play it. He was more accessible than Frankie.

Frankie had that aura about him. If you’ve ever met Frankie he’s like a toned-down character. He’s really even keel. He doesn’t seem that approachable, while Ron Hardy was a screamer. And Ron Hardy would sell his tapes – because he was a drug addict – he would sell his tapes. You’d say [desperate], ‘Ron can you make me a tape, Ron, please can you make me a tape.’

He’d say ‘$50.’

‘$50?!’

He’d say, ‘It’s worth a hundred.’ It was so fuckin’ funny when I finally got to know Ron Hardy.

So how much of an inspiration was Frankie Knuckles. Him coming to Chicago in ’77 and bringing the New York music. Was that important to Chicago?

Frankie Knuckles, yeah man. But you know Ron Hardy was playing in Chicago before Frankie Knuckles.

Yeah, back in the ’70s he played at a place called Den One.

Yeah, but then he went off to California.

Do you know why he went?

Who knows, man? But when he came back Frankie was the king. And Frankie went with some other guys and they opened the Power Plant. The owners of the Warehouse on the other hand, opened a new club called the Music Box. Now, of course they’re gonna have this rivalry thing right. For somebody to follow Frankie Knuckles, because all of Frankie’s people said, ‘Oh they’re opening a new club but they don’t have Frankie.’ So for Ron Hardy to make the Music Box like it was, was quite a feat.

To come in after Frankie.

Yeah, to come in after Frankie was something, ’cos he was ruling the roost. They were calling it house music now, and that was because of Frankie. And for Ron Hardy to come in there, and steal Frankie’s thunder, was really something. They were competitive: like two gunslingers. The Power Plant closed down, because of the Music Box. The Music Box just took everything; it took the Power Plant’s crowd.

Wow, they deserted Frankie?

It wasn’t deserted. People still liked Frankie, But it split off into two different crowds. The people that really liked loud, wild-ass music, and they were kids. When you have a situation like that, the kids are always gonna go to the wild-ass shit. You see this in rave music. And Frankie’s crowd turned into the people with like a more distinctive, a higher class of musical taste…

So the Music box was younger than the Power Plant.

Yeah, yeah, more energetic. And Frankie opened another club, CODs, right after Power Plant, and that closed down after a few months. Then he went to DJ at the Power House, which was owned by Italians. And before that they got the Music Box closed down.

Mobster stuff?

They didn’t want to be bothered.

Radio was really important, too: the Hot Mix 5. We’re they playing the same stuff you’d hear in the clubs?

They didn’t play the same records. The Hot Mix 5 would play more commercial stuff, a lot more European stuff. Like Falco, and stuff like that, Doctor’s Cat ‘Feel The Drive’, Klein & MBO. Well, Hardy would play Klein & MBO too, but Hot Mix 5 would play shit like Divine. You know, commercial shit. And more vocal stuff. A lot of stuff that came out of England. Hardy would play like your funkier disco stuff, underground stuff. ‘Optimo’ and ‘Cavern’ by Liquid Liquid. ‘Moody’ ESG, Atmosfear: that’s the kind of stuff Hardy would play. They wouldn’t go near that with the Hot Mix 5. But if you went by straight up mixing ability, the Hot Mix 5 would mix circles around fuckin’ Ron Hardy.

Did they play all together with a bunch of turntables, or did they take it in turn?

They would take turns, one of them at a time.

So just two turntables

Yeah just two turntables

A lot of people, like Pierre, said that was the first time they heard mixing.

Yeah.

“ For Ron Hardy to come in there, and steal Frankie’s thunder, was really something. They were competitive: like two gunslingers. ”

Was there anybody else who was really important but forgotten. Unsung heroes?

Oh shit? Unsung? Wayne Williams. Wayne was actually the guy that brought house music [ie underground disco] to the masses. Because Wayne would go to the Warehouse, and he really liked the stuff that Frankie was playing – the disco music. When Farley and Jesse heard it they were like, ‘Oh that’s that old fag music. That’s that old house music shit.’ you know they would joke about it. Jesse went off to college right. When he came back Wayne had made house music big. He brought it to the straight kids, right. And he was a damn fucking good DJ. And powerful minded too, because when he first did it, he used to clear the floor.

Because they dismissed it as fag music?

Yeah, but man he started banging it and banging it and banging it and, wheeeeew.

Where was his club?

He played all over, man.

When people started making records did you just take your masters into the pressing plant and ship things out yourself, and go sell them in the stores?

That’s what I tried to do. I don’t want to get into that too much…

There was a lot of shady dealing.

Yeah,

So if you wanted to press it up yourself, you still had to go to Larry Sherman at Trax, ’cos he owned the pressing plant.

So he had the option, at any time, to change whatever I brought him, to his record label.

And he had all the masters.

Yeah. And if you notice not a single record came out on my record label. I paid him to press up three fuckin’ songs [laughs]. You know.

So you gave him the labels and everything.

Yeah.

You had them printed up.

Yeah. Oh, you know about the labels. We got the labels, Adonis has the labels, of all those records. He saved them all these years.

What about royalties? Did you ever get any royalties from them?

No.

Nobody ever did, right?

No.

Did you know that when you went into…?

I didn’t care.

So you’d just get a one-off payment for a track?

I just wanted recognition. And I wanted to get pussy like Jesse and Vince. That’s what I wanted out of it.

So people were ready to be ripped off. They didn’t really care about money so much?

After me and the first generation got ripped off, the guys that came after us were a lot more wary, and they made sure they got money. For instance, like I talked to Pierre, and he was talking about getting $5,000. $6,000, $7,000 advances from Larry. I was [outraged], ‘You got WHAT?’

So they benefitted from your mistakes.

Yeah. A lot of stuff I really had to fight to get out out on Trax records. Like Fingers Inc ‘Can You Feel It’. Larry didn’t want to put it out. Like the ‘Virgo’ EP and ‘I’ve Lost Control’ and even ‘Move Your Body’. When I did ‘Move Your Body’, Larry Sherman said [Elmer Fudd voice], ‘That’s not house music, house music doesn’t have that fuckin’ piano in it.’ So I called it a house music anthem, you fuckin’ weener, you don’t know. He don’t have a fuckin’ clue. [Hilarity ensues] See!

“ I would hear people saying, ‘Yeah, I’m a buy me a acid machine so I can make some of that bullshit and make me some money.’ ”

How did you get into producing tracks for other people?

I was a songwriter, I needed people to sing. And that’s when I ran into Byron Stingily, you know I was already working with my friends from the Post Office. Curtis McClain sung ‘Move Your Body’, but that wasn’t really working for other people, he was my buddy.

What happened to him?

I don’t know. Curt wasn’t really a hard worker. He would always say he could do something but he would never do it. I was the hardest working guy, out of my friends from the Post Office, ’cos there was bout five of us, and we all wanted to make records, but I was the only one that wound up making them.

You helped a lot of people get their music onto record.

I helped everybody. I started everybody. I started damn near everybody off, man. I gave Steve Hurley his first major label remix, and Frankie Knuckles his first major label remix. Lil Louis, I physically did his first record, ‘The Video Clash’. DJ Pierre. Man, a lot of the Trax Records guys. Fingers Inc ‘Can You Feel It’, would have never come out if it wasn’t for me. I just knew it was special.

You helped Pierre produce ‘Acid Tracks’?

Yeah, yeah. Yeah. That shit wouldn’t have come out if it wasn’t for me. Pierre gave me a tape, of ‘Acid Tracks’. And I called him the next day, I said, ‘Okay let’s do it.’

You didn’t know him before that

Never heard of him.

What did you think of the acid sound?

I liked it when Pierre did it. I didn’t like it when everybody else did. I would hear people saying, ‘Yeah, I’m a buy me a acid machine so I can make some of that bullshit and make me some money.’ It’s that attitude.

Was the money because the acid sound had started making it in the UK?

Well, that’s what started separating house music. Acid house was the start of them separating it into different things. ’Cos shortly after acid house you had techno, and you had the New Jersey sound, and trance, and all that shit. It split. And before that it was just house music.

When was the first time people in Chicago realised it was hitting in other places?

Shit, when everybody started coming to the city wanting to interview everybody and talking about house music. That’s when we knew.

1986?

Yeah. That’s when everybody started panicking, tripping over each other, and holding each other back.

What would have happened if there hadn’t been any powerful DJs in Chicago. Would kids have still made all these tracks?

No. Definitely not.

It’s funny how you say that Jesse was the guy who started it off by inspiring people because his music was so basic.

Jesse changed music, man. Even though I was listening to dance music, I wouldn’t have made any of it if it wasn’t for Jesse Saunders. I wouldn’t have thought that I had the ability, or the chance, to get music out there.

That’s what got Todd Terry into it. That’s what got Masters t Work into it. That’s what got David Morales into it, man. Because they thought, ‘Fuck I can do that.’ When that shit came out, all them New York guys got into it. Said, ‘Fuck, man, I can do this.’ And the same thing when it hit London: ‘Fuck, I can do this. This is great.’

© DJhistory.com

MARSHALL JEFFERSON SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

MARSHALL JEFFERSON – Move Your Body (The House Music anthem) (producer/writer)

ON THE HOUSE – Pleasure Control (producer/writer)

VIRGO – R U Hot Enough (producer)

KYM MAZELLE – I’m A Lover (producer)

TEN CITY – Devotion (producer/writer/arranger)

STERLING VOID – It’s Alright (producer)

SLEEZY D – I’ve Lost Control (producer/writer)

ON THE HOUSE WITH MARSHALL JEFFERSON – Ride The Rhythm (producer/writer)

HERCULES – 7 Ways (producer/co-writer)

ON THE HOUSE – Give Me Back The Love (producer/writer)

JUNGLE WONZ – The Jungle (producer/co-writer)

MARSHALL JEFFERSON PRESENTS TRUTH – Open Our Eyes (producer)

JUNGLE WONZ – Time Marches On (producer/co-writer)

TEN CITY – That’s The Way Love Is (producer)

JUNGLE WONZ – Bird In A Gilded Cage (producer/co-writer)

TOM TOM CLUB – Oceana (remixer)

TEN CITY – Superficial People (producer)

UMOSIA – We Are Unity (producer)

WHAT IT IS – Do You Believe (producer)

RICHARD ROGERS – Can’t Stop Loving You (producer)

DUSTY SPRINGFIELD – Nothing Has Been Proved (remixer)

MARSHALL JEFFERSON VS NOOSA HEADS – Mushrooms (vocals)

RECOMMENDED LISTENING

MARSHALL JEFFERSON – Timeless Classics

VARIOUS – Tribal Gathering ’96

VARIOUS – Chicago House 86-91: The Definitive Story