Juan Atkins

Techno rebel

Interviewed by Ben Ferguson by phone to Detroit, April 21, 2010

Given the huge impact he has had on music worldwide, Juan Atkins is possibly the most overlooked black artist in America. Of the fabled Belleville Three (with Kevin Saunderson and Derrick May), Juan is the key to techno, the sound that emerged from this leafy Detroit suburb. Son of a concert promoter, the young Atkins played in high school funk bands and most days was to be found padding around his house with a bass guitar more or less permanently slung round his neck. When his grandma bought him a synth his focus changed completely and he spent days at a time programming beats in the image of the European electronic bands he loved.

Juan began making records with Rik Davis in the early 1980s under the name Cybotron. In another universe it could have been their eerie ‘Alleys Of Your Mind’, rather than a broadly similar (and slightly later) record called ‘Planet Rock’ which ignited electro worldwide. His subsequent solo productions as Model 500, although clearly inspired by a European aesthetic, are among the most inspired productions to come out of black America.

While Derrick May wanted to call this music ‘high-tech soul’, Juan was insistent that it should be ‘techno’. At the last minute the compilation which introduced it to the UK – originally to be called The New House Sound Of Detroit – was renamed along these lines. And techno, of course, went on to conquer the world. If any one person could be said to have started it, it must surely be Juan Atkins.

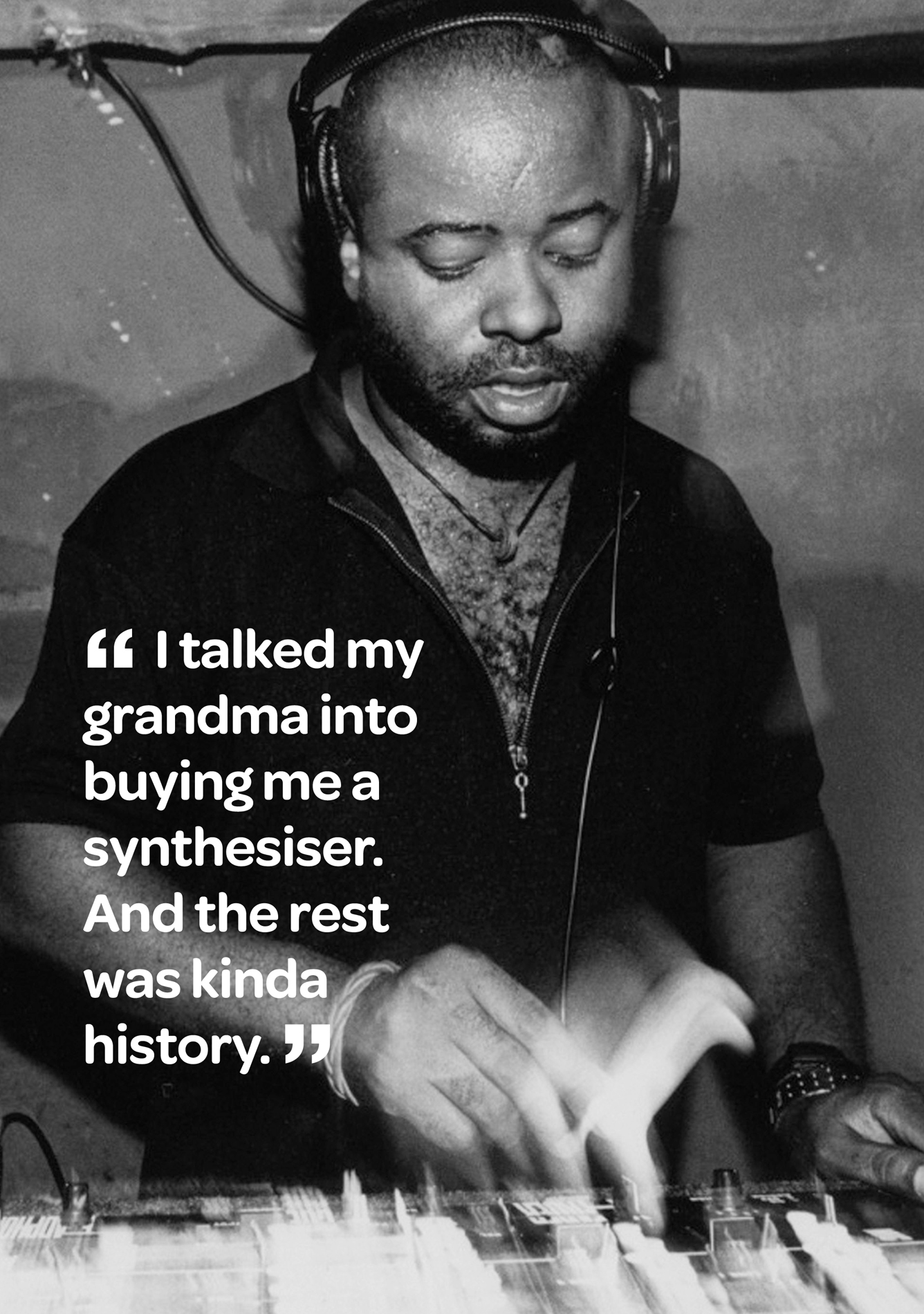

“I talked my grandma into buying me a synthesiser. And the rest was kinda history.”

You moved to Belleville when your parents split. What was surburbia like?

Well actually what happened was, we were about to move to California but then my father’s ma, my grandmother, called us at the last minute and said they’re building a new house down the road from me. And talked him into it. It was very very different from inner city life. We lived in Detroit before that.

How old were you?

Like 14, 15.

Were you already listening to a lot of music?

Yeah, yeah, I’d always listened to music. In Detroit I was playing in funk bands, garage bands with friends of mine off the street and around the block, and we’d get together and play in the garage. I played bass guitar. Some lead guitar. So we’d all get together and watch people. This was when I was 12, 13.

Who else played in these bands?

A guy named Jimmy Smith, Chris… I can’t remember his last name, Keith Jameson, a couple of other people. I can’t remember everybody’s names.

Did you keep in touch with them after moving?

Not really. When I moved to Belleville it was kind of a wrap for them. When I went to Belleville I started a whole new band.

Still playing funk?

Yeah. Well that was the era. It was the funk era – ha! And a little disco. But then funk became disco, then disco became new wave, then new wave and disco became house and techno.

Your dad was a concert promoter wasn’t he.

Yeah, he’d run people like Norman Connors, Michael Henderson, Barry White; he did a big Barry White show down at Cobo Hall.

Did you meet any of the stars?

No, we just went to the show and that was it.

But the shows must have been good.

Yeah, I remember Michael Henderson particularly, because I liked ‘Wide Receiver’. That was a big track for me in high school so when he ran that definitely it was memorable for that one track.

And did you ever think about stardom of this sort?

You know, we were just having fuuuun [southern accent]. We didn’t think about stardom or being famous. We were just kids doing what we liked to do. I would have imagined that there was a little bit of that but really we were just stars in the garage. So you know… When you pick up an instrument there’s a bit of you that definitely dreams of being a superstar. That goes without saying. But we wouldn’t get around in a group discussion and say, ‘Hey, let’s try be superstars.’ I mean, it was just something that was an unspoken rule. Unspoken rule to be famous basically…

Like how nobody is allowed to admit that they want to make money.

Well, not everybody.

And your brother was living with you as well. By the sound of it he made a big impression on Derrick May, especially the day when he rolled up in his Cadillac with Parliament pumping out of the speakers

[Laughs] Well my brother was a year younger than me. He and Derrick were in the same class ’cos Derrick is a year younger than me too. He would prowl around with my brother before we became friends.

How was your relationship with him?

He’s my younger brother. I love him, we’re one of the same. But the funny thing is back then I’d hang out with an older crowd. We didn’t hang out with the same sort of people.

Were these guys much older than you?

Yeah. Mostly neighbourhood friends.

Did they play you stuff you might not have heard if you hung out with kids your age?

Probably, probably, probably.

So it wasn’t long before you put down the bass and picked up the synth?

Basically, when I moved to Belleville I started playing the keyboard. My grandmother owned an organ, this hammered old B3 thing. She’d go into the music shop, Brunel’s, for this organ. And right at this time they’d introduced the Minimoog, the Korg NS10, these were small, smart monophonic synthesisers. I’d go into the back room and play these synthesisers and eventually I was able to talk her into buying me one. And the rest was kinda history. I was so wrapped up in this sound, with playing around with these synthesisers. I made drum sounds, drum kicks, everything, all on this one synthesiser. And that’s how I started doing my demos and my electronic music demos. And by the time I got to college I had full-blown demos that I played for classmates.

How old were you then?

15, 16.

What did your dad make of this?

By this time my father wasn’t around too much. He was into the street and wasn’t really paying too much attention to what was happening at home. Whatever I did in my bedroom that’s what I did was my own and no one would come in, especially my dad.

Were you not getting on with each other?

No, no, we were great but he was in control of the nightlife and he wasn’t at home a lot.

One difference between playing in bands and using a synth is that music can be made alone. All you needed was your bedroom, yourself and the machine.

Yeah. Well the thing is, being in Belleville the next person I could play with was 10 miles away. It was hard for me to get together with other musicians.

Did it feel like you were doing something unusual?

There weren’t too many other people doing that. I was very innovative when I was young. I knew I was doing stuff that was not the normal thing to do.

Was this in reaction to anything? The high school parties perhaps?

No. Not a reaction. This wasn’t happening in Belleville. Belleville was different to the inner city schools.

Did you go to these parties?

Yeah, of course.

“ I was very innovative when I was young. I knew I was doing stuff that was not the normal thing to do. ”

What did you think?

It was great. All the pretty girls were there.

Did you find out about music from there as well?

Well I grew up to funk. But basically on the radio, where Electrifying Mojo was playing a lot of stuff that influenced my early years. Sometimes I’d just go in the record store and buy stuff based what the album looked like.

Electrifying Mojo inspired a lot of people. What made him different?

He owned his own show, he was in control of whatever he wanted to play. He didn’t have a format imposed on him by the programme director. He was an individual, a personality. And quite a personality he was. He played a huge variety of music and exposed a people in Detroit to a lot of different things that they probably wouldn’t have otherwise heard.

Like what?

He would play a half-hour of James Brown then turn around and play a half-hour of Jimi Hendrix and then turn around a play a half-hour of Peter Frampton, Parliament Funkadelic. You name it. He brought Prince here. First place I heard Kraftwerk. Believe it or not he’d play America, ‘A Horse With No Name’.

Really?

Yeah [laughs], he’d place ‘A Horse With No Name’, stuff like that.

Where did his style come from?

Mojo was on the radio in Vietnam and when you ask him he’d say that’s where he got his eclectic format. He had to play a variety of stuff to his soldiers in Vietnam. I can’t remember what city he was in but it had something to do with that. In fact, he was in the Philippines. It must have been playing to all soldiers, that’s where he got his strong host of Hendrix, Frampton, America.

Another guy who’s famously a Vietnam vet is Rik Davis, your bandmate in Cybotron. How did you meet him?

I met him in my first year at community college. In one of my music courses. I brought my electronic demos to school and when I played ’em everybody wanted to hook up with me because they were so different. So wild. So Rik wanted to hook up with me and play music because he was an electronic musician like myself.

Did he play anything to you?

No, it was only at his house that I got to hear his stuff. He was much older than me, like 10 years and didn’t bring anything in to college to show.

Did he have all kinds of tales from the war?

Yeah he had a couple of stories. He told me one time that him and a whole brigade went into the bush and he was the only one that survived. He saw stuff like that. All of his friends in the army got killed.

Was there something that made you click with one another?

I’m sure there was. There must have been for us to come together and put Cybotron together but what that thing was I can’t quite put my finger on. There was definitely something.

I was a kid though – 17. He was like a father figure to me. He taught me a lot. We didn’t have so much in common. I was in awe with him. My father was in jail at the time.

“ Jesse Saunders, Chip E, these guys started coming out with records at around the same time as Metroplex started. It was like a cultural exchange between Detroit and Chicago. ”

Techno is often seen as white music. Did you and Rik ever talk about race in relation to your music?

No. Why would we do talk about race? We talked about music, and race didn’t come into it. I mean we knew we were black, and we were in America. There was nothing to talk about, those were our circumstances. We had a white guy in the band in fact. He played guitar, controlling the synth with his guitar. If you listen to records like ‘The Line’, ‘Industrial Lies’ and ‘Enter’, all of that guitar work was Jon 5. A lot of my core persuasion was funk music. That could be considered to be black music but we never said, ‘Hey we’re making black music.’ No, we were making electronic music.

And then ‘Clear’ spent nine weeks on the black music chart!

Okay, well we knew we weren’t making rock’n’roll. We were playing in someone’s church and it wasn’t rock’n’roll.

I guess that’s where you and Rik went your separate ways, when he wanted to take it in a rock’n’roll direction.

I think that that was where his mind was. He was heavily, heavily Jimi Hendrix-influenced. You could call him Jimi Hendrix on the synthesiser. I think that was where he more wanted to be in that album-orientated rock.

Meanwhile you had these bubbling aspirations for Metroplex.

Yeah. I started Metroplex in order to release my sound. It was a continuation of the more funk, bass, electro-bass tracks.

You knew you were going to do that from a young age.

Yeah.

Did Cybotron help you realise Metroplex?

Yeah, for sure.

Hopping back a little bit, can we talk more about your relationship with Derrick?

Okay, well he came to live with us after high school. After ‘Alleys Of Your Mind’, ‘Cosmic Cars’. Right around that time Derrick was very instrumental in helping me promote the records. I was living in Detroit with my grandmother and Derrick was living with us there.

Tell me how Deep Space came about.

Well it was the label that Rik and I released Cybotron out of, but then Derrick and I took the name and it became the sound company that we did parties under and it worked well for me and Derrick.

So you were back in Detroit. Did the move home effect what you thought about music?

Probably not.

Did it change the way you thought music should be heard? You started putting on parties.

Yeah but I don’t think the move to Detroit changed something.

What were your parties like?

It was the same. It was only a couple of years after we were going to the parties; the only difference was we were now spinning the parties. Same mix of people, same crowd but this time we were DJing.

Did you play your own music?

Yeah – we played ‘Alleys Of Your Mind’, ‘Cosmic Cars’ and got a great response. Those records were huge. By then Mojo was playing the records, we were famous in Detroit.

How did Mojo get your records?

We gave them to him. He heard the demos of our stuff, and liked the demos and that was what really prompted us to play the records was that Mojo liked them. He was like ‘I like it’, and we went away and pressed it, took it back and he kept his word and played the records.

And did you think from then on things had changed?

No. But I loved the music, I was very confident but where we were going was a mystery to me. The thing is, Just ’cos I liked it didn’t mean that another person on the planet had to like it. So I didn’t know. I figured it was going to be good.

I don’t think the record got the recognition it should have got. Actually. Because of different radio politics, it was hard to get a record distributed nationally in different cities in the States. It’s not like the UK where you’ve got Radio 1 and everybody hears everything all at the same time. Especially during the early ’80s when radio was fragmented. Now it’s more across the board, if a record is big in New York it gets passed across the cities. Back then you had more personality style DJs and radio would sound different from city to city, you didn’t have one radio station across the country. A record that was popular in Detroit might not necessarily even be heard in Chicago or Cleveland and vice versa. There’d be records that if you went on a road trip and you went to Chicago that you thought. ‘Wow I never heard this record,’ simply because it never made it to Detroit.

That sounds like another world now.

Yeah, yeah. Even before the internet in the last 10 years, I mean radio has become more centralised but back then it was more fragmented.

Had you ever left Detroit by then?

Well what happened was Derrick’s parents had moved to Chicago but he was still in high school so he had to stay here to finish up his high school. But he would go there and he would tell these stories about the clubs and who he met and about the radio. And that was my first introduction to Chicago. By the time I started Metroplex he took some of my first records down there, my first copies of ‘No UFO’s’ – my first release on Metroplex – and took it down there and gave it to Farley Jackmaster Funk and Farley broke that record over there and played it in his mix. Farley made it the biggest record in Chicago; Farley made it bigger than it was in Detroit.

Did you know about Chicago house?

Well, there wasn’t any house at that time. There was nobody there making records in Chicago. I honestly believe our record… When Derrick went down there and gave it some of the guys like Jesse Saunders – which was kinda like the first house record – Chip E, these guys more or less started coming out with records at around the same time as Metroplex started. It was like a cultural exchange between Detroit and Chicago.

Clubs in Chicago were playing disco?

Yeah, mainly disco. I mean if you listen to some of the early Hot Mix 5 it was just a continuation of disco. A lot of the Hot Mix 5 mixes were Italo-disco tracks because Italians kept making disco records after 1981, and that was the stuff the Chicago boys were playing. And ultimately after that they started making their own stuff. But when you listened to the Hot Mix 5 mixes 80 percent of it was Italo disco.

So it was way more Italo than in New York?

Well New York was earlier. New York was West End, Prelude, Salsoul. All of that stuff fell to the wayside when disco left. They were the disco kings.

Was there any Italo being played in Detroit?

No. Detroit was a hick town compared to Chicago. We had the social club parties, where we heard a little bit of that. Not on the radio though.

“ We just wanted to DJ. Our thing was about the music. Even to this day. We haven’t hosted that many parties but we definitely wanted to DJ at as many we could. ”

For people who were making music, were parties the thing to aim for? Did you want to become the tastemakers?

Yeah, but we didn’t want to necessarily host our own parties, we just wanted to DJ. We didn’t care who hosted the party. You know? Our thing was about the music and it’s always been about the music. Even to this day. We haven’t hosted that many parties but we definitely wanted to DJ at as many we could.

Ken Collier was the best-known club DJ in Detroit. And there was a party where you guys opened for him.

Yeah, that was very enlightening because he was the king. We learned a lot from Ken.

Did it seem like a big deal?

Yeah, there were stints when he had mixes on the radio during the disco era but when disco died they didn’t want mixes anymore. But Ken was a main guy when they did have the mixes. He was an icon. We were honoured to play with him; we were glad that he wanted to play with a couple of unknown DJs.

What happened when you started to focus on producing music as Model 500?

I took a step back from DJing for a while. Derrick continued to DJ because he wasn’t making music but when I started Metroplex I did take a step back for a few years. And then records got exported to the UK so I started back up then so I could go to Europe.

So you were inspired by a band from Europe, Kraftwerk, and you then found yourself going back over there.

Yeah. But you gotta remember that the electro thing had kicked of in Europe. ‘Clear’ and ‘Techno City’ were included on a set of Essential Electro compilations so it wasn’t like it was the first time I was exposed to Europe.

Did you think about ‘Techno City’ as a Detroit export?

No, I had no idea that it was as big in the UK as it was.

Europe was maybe a bit more open to experimental electro. Do you think you added some soul to it?

I guess you could say that.

But is that what you’d say?

Erm, I guess you could say that.

You’d heard a lot of European stuff, like Kraftwerk, obviously, and Manuel Göttsching?

‘E2-E4’ was a great track. It was more on an ambient vibe. Like a summer breeze.

Not dance music

No.

There was something about your rhythms that turned this style into dance music.

Well my style was always dance music. I think that from the beginning everything I had done was very danceable. My first record ‘Alleys Of Your Mind’ was very danceable.

Did you always want to make dance music?

That’s my forte.

© DJhistory.com

JUAN ATKINS SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

CYBOTRON – Alleys Of Your Mind (writer/producer)

CYBOTRON – Cosmic Cars (writer/producer)

CYBOTRON – Clear (writer/producer)

CYBOTRON – Techno City (writer/producer)

X-RAY – Let’s Go (remixer)

MODEL 500 – No UFO’s (writer/producer)

JUAN – Techno Music (writer/producer)

TRIPLE XXX – The Bedroom Scene (producer/mixer)

NASA – Time To Party (Engineer/remixer)

MODEL 500 – Night Drive (Thru Babylon) (writer/producer)

KREEM – Triangle Of Love (writer/producer)

MODEL 500 – Testing 1-2 (writer/producer/mixer)

INNER CITY – Big Fun (remixer)

THE BELOVED – Your Love Takes Me Higher (remixer)

DR ROBERT & KYM MAZELLE – Wait (remixer)

MODEL 500 – Interference (writer/producer)

VISIONS – Is This Real? (producer)

INNER CITY – Good Life (remixer)

3MB FEATURING JUAN ATKINS – Die Kosmischen Kuriere (writer/producer)

JACOB’S OPTICAL STAIRWAY – The Fusion Formula (producer)

RECOMMENDED LISTENING

VARIOUS – Techno! The New Dance Sound Of Detroit

MODEL 500 – Classics