By 1944 Japan was well and truly on the defensive. The glorious victories of 1941 and 1942 all across the Far East and the humiliation of the Allies were now just dim memories. In Burma, their offensive towards Imphal and Kohima had failed. By July, British and Commonwealth troops were pushing them back into central Burma.

President Roosevelt met with Admiral Nimitz and General MacArthur in July 1944 in Honolulu, Hawaii, to discuss Operation Stalemate, the planned assault on the Palau islands group, A target date of 8 September was set; this was subsequently revised to 15 September.

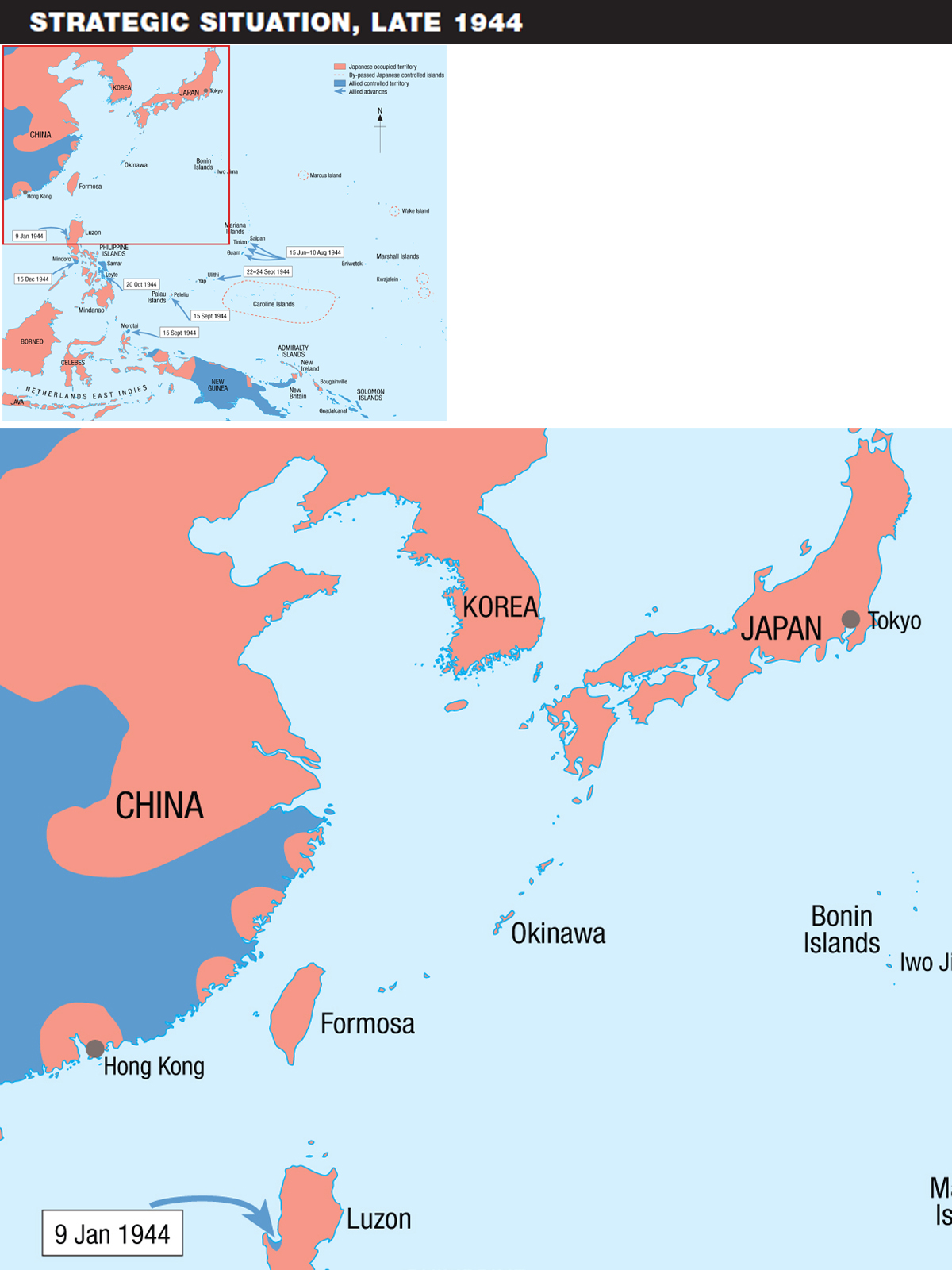

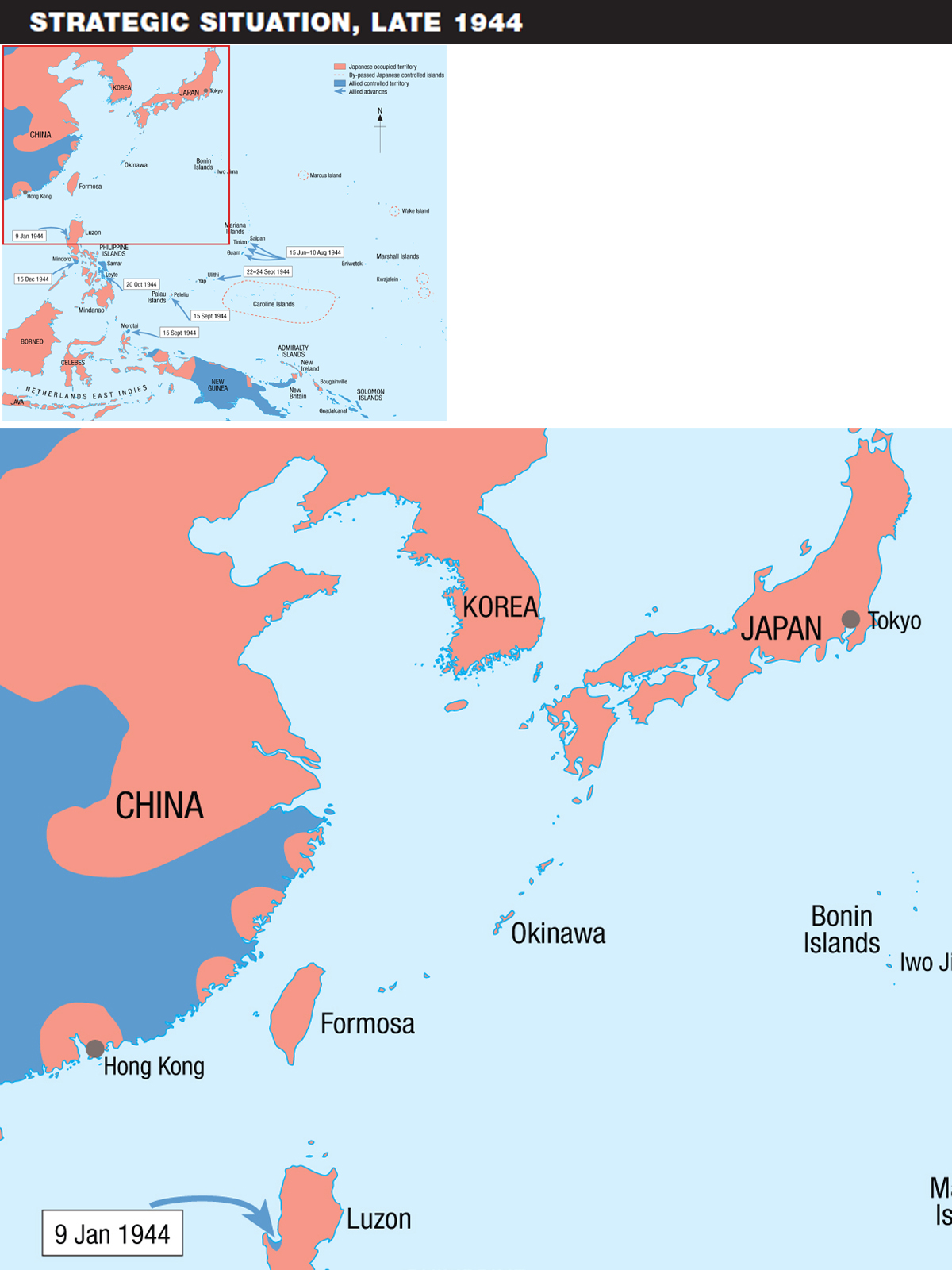

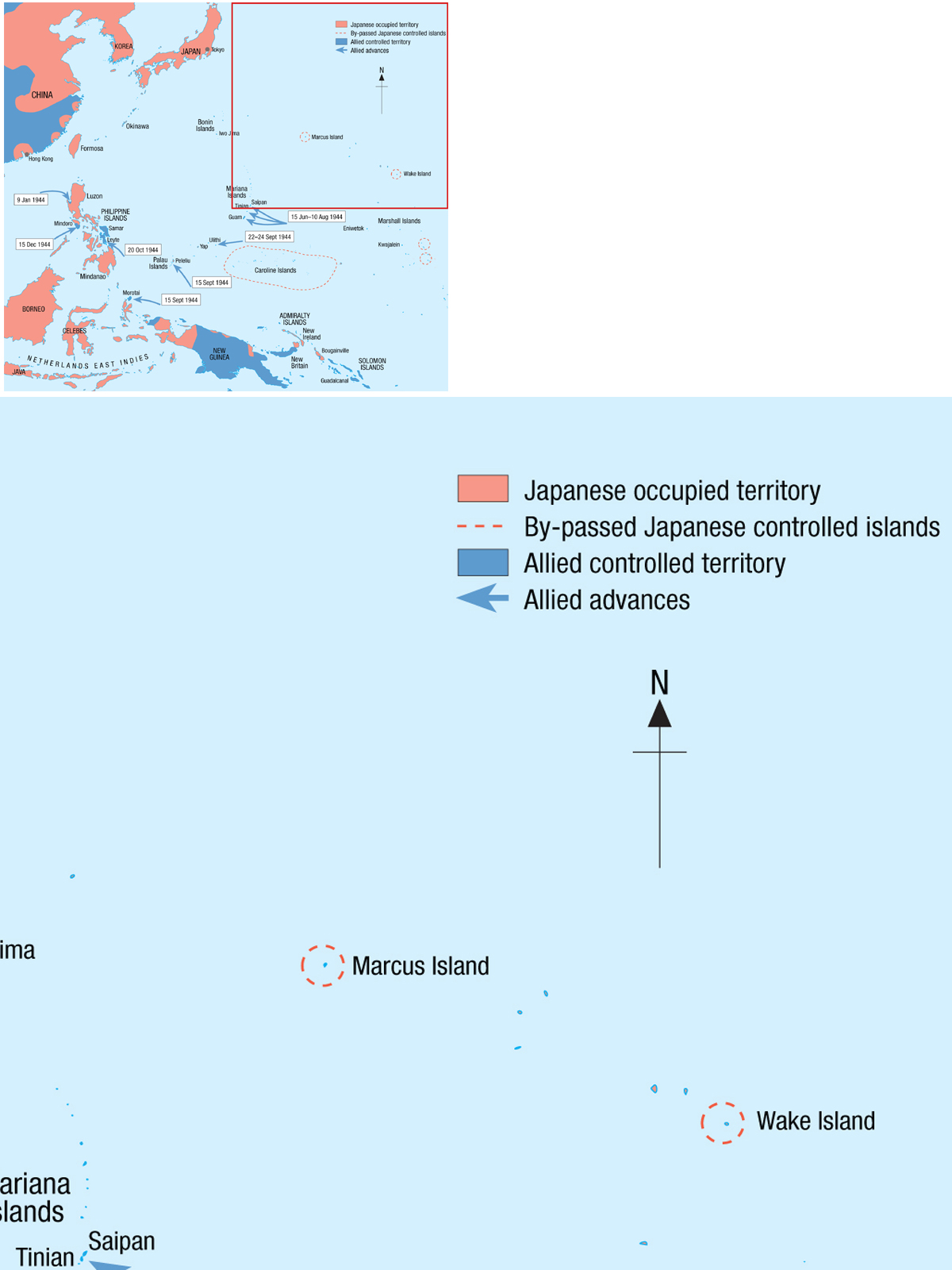

In the Northern Pacific, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s forces had successfully “island hopped” from Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands in November of 1943, on to Kwajalein and Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands in early 1944 and to Guam, Saipan and Tinian in the Marianas, which were secured by August of 1944. Now Nimitz and his team had their sights set on Iwo Jima and Okinawa and the final objective, the Japanese Home Islands.

The delays in securing the Marianas would have two effects upon the Peleliu operations; firstly the delayed arrival of the III Amphibious Corps Commander, MajGen Roy S. Geiger, USMC, to take up his post, by which time planning for the Palau Islands operation was complete and he would have little time to change anything. Secondly, the inter-branch rivalry between the Army and the Marine Corps came to a head when LtGen Holland (“Howlin Mad”) Smith, USMC, relieved MajGen Ralph C. Smith, US Army, of his command of the Army 27th Infantry Division for “defective performance.” This act was to have serious repercussions all the way back to Washington, DC and the smoke from this serious bust-up was still much in evidence by the time of the Palaus operations. It must be said however that the two major players in the forthcoming operations, the 1st Marine Division (Mar. Div.) and the Army’s 81st Infantry Division (Inf. Div.), would perform very well together with no repetition of what occurred on the Marianas.

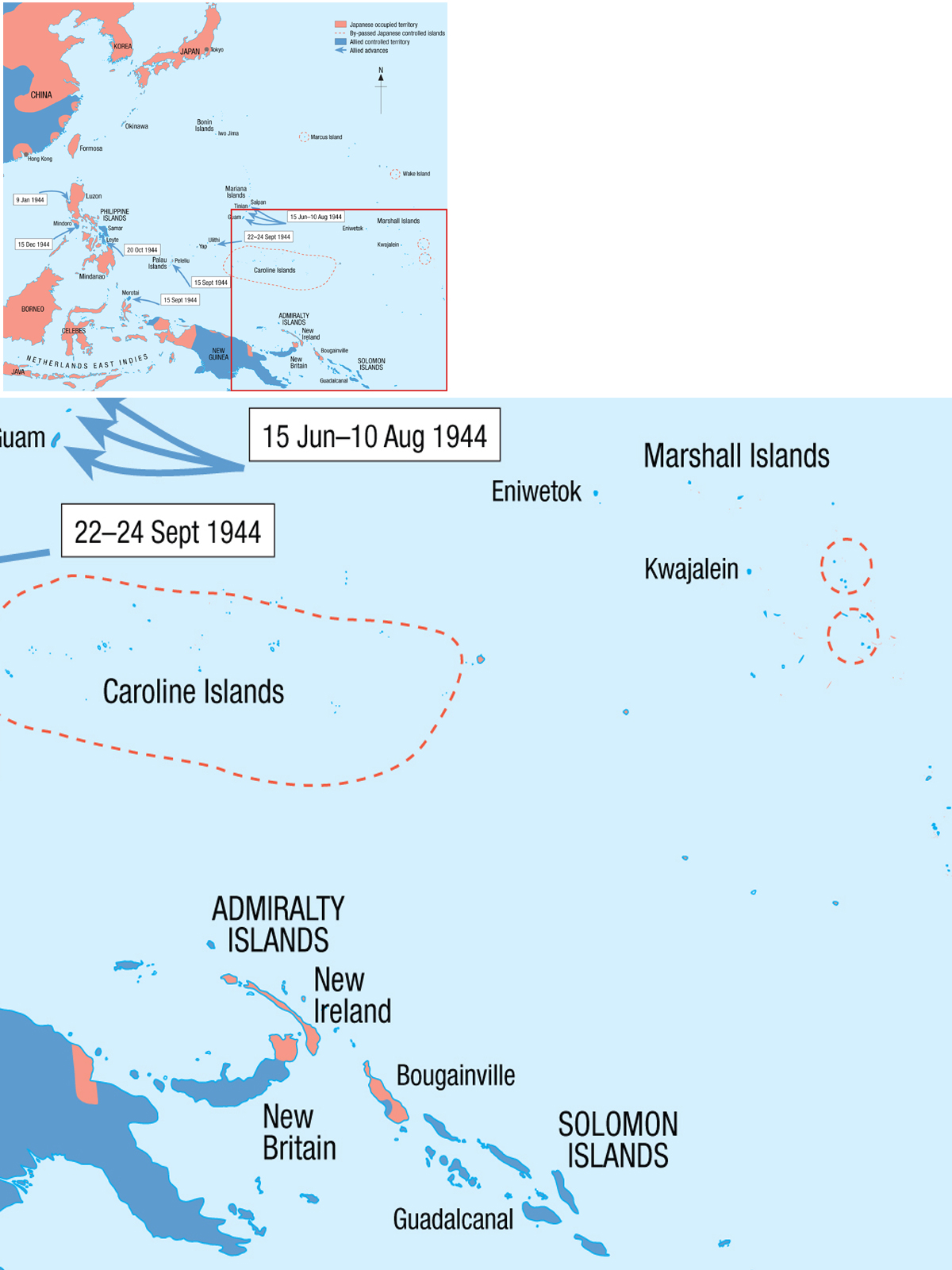

In the Central Pacific, General Douglas MacArthur’s forces had, since August 1942, worked their way from Guadalcanal up through the Solomons chain of New Georgia, Bougainville, New Britain, and across New Guinea. General MacArthur was now ready to fulfill his promise of “I shall return,” made to the Philippine people when he was ordered to leave by President Roosevelt in the dark early days of 1942.

The successful carrier-based air strikes on the Japanese naval bases at Truk in the Caroline Islands and at Rabaul in the Solomons had neutralized them sufficiently to allow them to “wither on the vine.” They were no longer a barrier to progress. MacArthur was determined to return to the Philippines as early as possible and in July of 1944 met with President Roosevelt and Admiral Nimitz in Honolulu. He argued that his failure to fulfill his pledge to return at the earliest possible moment would not only have an adverse psychological effect on the Philippines, but would also seriously diminish America’s prestige amongst her friends and allies in the Far East. MacArthur was so persuasive that he even won over Admiral Nimitz, to the extent of once again securing the loan of the 1st Mar. Div. as he had done for the re-taking of the Solomon Islands. Earlier in May 1944, Admiral Nimitz had already issued a warning order for the invasion of the Palau Islands group under the codename of Operation Stalemate. The target date was set for 8 September 1944.

Admiral Chester Nimitz, as Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet and Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas (CINCPAC – CINCPOA), was in overall command of Operation Stalemate II and it was his final decision that the invasion of Peleliu would go ahead.

Initial plans were for MacArthur to push north from New Guinea to Morotai and then on to the Philippines. With the Philippines back in US hands, the decision could then be made whether to assault the Japanese mainland via Formosa and China, favored by MacArthur, or from Okinawa and the Ryukus Islands as favored by Nimitz. On the same day as MacArthur’s troops landed on Morotai Island in the Netherlands East Indies between the Philippines and New Guinea, the 1st Mar. Div., supported by the 81st Inf. Div., were to make landings in the southern Palaus on the islands of Peleliu and Angaur, as part of Operation Stalemate II, the revised plan for assaulting the Palau Islands. The original plan, Operation Stalemate, had to be revised due to the delays in the Marianas campaign the troops and shipping from which constituted a large portion of the resources for Stalemate. The revised target date for Operation Stalemate II was to be 15 September 1944.

Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, as Commander of Western Pacific Task Force, was in overall charge of the supporting operations and, whilst the invasion force was plowing towards the Palaus, he carried out air strikes with carrier-based planes on the southern and central Philippines, as well as air strikes against the Palaus, all part of the pre-invasion preparations.

One thing was becoming apparent as a result of these air strikes; although inflicting heavy damage to enemy shipping and aircraft, the raids on the Philippines were only lightly contested. This suggested to Halsey that they were not as heavily defended as everyone had at first thought. So convinced was he that he was right, Halsey ordered his chief of staff, Rear Admiral R.B. Carney, to send an urgent message to Admiral Nimitz on 13 September, just two days before the planned assaults on Morotai and the Palaus, recommending:

1. Plans for the seizure of Morotai and the Palaus be abandoned.

2. That the ground forces earmarked for these purposes be diverted to MacArthur for his use in the Philippines.

3. That the invasion of Leyte be undertaken at the earliest possible date.

Upon receiving the urgent communiqué, Admiral Nimitz reacted quickly to Halsey’s suggestions and in turn sent his own communiqué to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who were then in Quebec for the Octagon Conference with President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill. The Joint Chiefs consulted with General MacArthur and on 14 September, the day before D-Day on Peleliu, it was decided to speed up the landings on Leyte by two months – confirming point 3 of Halsey’s recommendations to Nimitz. Points 1 and 2 of Halsey’s recommendations were, however, ignored. This would have little effect on the 31st Inf. Div. assaulting Morotai, which cost little in blood, but for the 1st Mar. Div. and the 81st Inf. Div. this decision would cost them over 9,500 casualties.

Several new innovations were tried as part of the assault landing phase on Peleliu to overcome the obstacle of the coral reef, which was impassable for conventional landing craft. These included amphibious trailers towed by LVT amtracs and fully waterproofed Sherman tanks that could wade the 700 yards from the reef to the beaches. Also engineers’ barges with crawler cranes were employed at the reef’s edge for speedy transfer of supplies and ammunition to the beachhead by LVT amtracs.

Admiral Nimitz never fully explained his decision to overrule Halsey, saying only that the invasion forces were already at sea, that the commitment had already been made and that it was too late to call off the invasion. The Palau Islands had excellent airfields from which an invasion force against the Philippines could suffer air attacks. Also, there were several thousand first-rate troops who could be sent to reinforce the Philippine garrison. Both factors, Halsey insisted, could be dealt with by the use of air strikes and naval bombardments, without having to commit ground troops, but Nimitz overruled him.

Halsey would always disagree with Nimitz’s decisions regarding Morotai and the Palaus, claiming that whatever the value of the airfields and anchorages afforded by the Palaus, the cost of taking them would be too high. A view many a soldier and marine on Peleliu would agree with.

From the Japanese perspective, the loss of the Marshall Islands and the heavy raids on Truk and the by-passed Caroline Islands necessitated serious consideration to the defense of the Home Islands. On all fronts, the Japanese were being pushed back and it was becoming apparent that a different approach would be required in the light of the pending invasion from the Allies.

The result of these serious deliberations was what became known as the “Absolute National Defense Zone.” A line drawn in the sand, to be held at all costs. Part of the “National Defense Zone” was the Palau Islands. In 1944, after meetings and consultation, Premier Tojo summoned LtGen Sadao Inoue. Sadao’s 14th Division had been transferred from Manchuria to the Palau Islands. There, Sadao was to prepare defenses and ready himself for the anticipated Allied invasion.

LtCol Nakagawa Kunio, Commander of the 2nd Infantry Regiment (Reinforced), appointed to the defense of Peleliu and Angaur. A most able tactician, as he was to prove on Peleliu, and probably ranking with General Kuribayashi, the defender of Iwo Jima, as Japan’s most talented tacticians.

Beach Scarlet photographed after the island of Peleliu had been taken. This was one of the beaches discarded as a possible landing beach, due to the danger of troops converging on fellow assault troops advancing from Orange Beach. As can be seen from this photograph, Beach Scarlet was covered with antiboat obstacles including coconut log barriers, barbed wire entanglements, and hundreds of antiboat mines.

The Palau Islands and the rest of the Japanese Mandated Territory (Marshall, Mariana, and Caroline Islands) had first been seized by the Japanese after declaring war on Germany in August 1914, with Admiral Tatsuo Matsumara landing on Koror in October of that year. In spite of American opposition, the League of Nations mandated control of the islands to Japan in 1920, effective in 1922. Japan established the South Sea Defense Force to secure the Mandate and it was administered by the South Sea Bureau with all commercial enterprises run by Japanese firms. Coconuts and fish were the main exports. By the early 1930s Japanese colonists far outnumbered the native population.

During the intervening years between World War I and the outbreak of World War II, Japan established a major presence on the Palaus, centered around Koror, with a civil government and a major Japanese commercial activity, but the islands always remained somewhat shrouded in secrecy. In fact it was on Koror Island that LtCol Earl (Pete) Ellis, USMC, died under mysterious circumstances in 1922 whilst “touring” the Pacific (he was in fact spying for the US Government). Ellis had argued the inevitability of a clash in the Pacific between the United States and Japan.

Japan withdrew from the League of Nations in 1935 and closed the Mandate to westerners. Japan began establishing military and naval installations throughout the Mandate, but with the exception of Truk, where a large forward naval and air base was built, most of these installations were minor. They included airfields, seaplane bases, submarine bases, and minimal coast defenses. The 4th Fleet, and amphibious force, was organized in 1939 to defend the islands.

But, following the outbreak of hostilities in December 1941, the Palau Islands took on a more important role, first as a forward supply base and training area for the Japanese conquests of 1941 and 1942, but now in 1944 they were on the front line of the defense of the homeland. Before the arrival of General Sadao and his forces, the Palau Islands were defended by troops under the command of MajGen Yamaguchi. Yamaguchi’s troops would bolster Sadao’s forces for the defense of the Palaus.

The Japanese, after detailed surveys, assumed correctly that the Allies would probably assault from the south, with landings on Peleliu (for the airstrip) and Angaur, then make their way up the Palaus chain, heading for Koror and Babelthuap. As events would transpire, though, this would prove unnecessary to the Allies, being able to neutralize the Japanese forces on these islands with the use of air and naval supremacy from their newly acquired bases on Peleliu and Angaur.

MajGen Murai Kenjiro, sent from Koror island headquarters by General Inoue to Peleliu to add rank to Col Nakagawa, who was experiencing severe difficulties in cooperation from the naval garrison under the command of Vice Admiral Seiichi Itou. It would appear that Murai acted to all intent and purposes as an advisor to Nakagawa, not taking over command as a General should. Murai would serve on Peleliu throughout the battle at Nakagawa’s side, eventually the two committing suicide.

The Palau Islands, or Parao Shoto as the Japanese called them, are on the extreme west end of the Carolines. Yap is 350 miles to the northeast, Truk just over 1,000 miles to the east, Guam is 730 miles to the northeast, and the Philippines are 600 miles to the west. Tokyo is 2,400 miles north and Hawaii 4,600 miles east-northeast.

The Palaus contain some 100 islands and islets about 100 miles from southwest to northeast. A barrier reef runs along the west side of the islands from just northwest of Peleliu, looping out from the central islands, along the west side of Babelthuap, and around the island’s north end at the Kossol Passage. The reef provides a protected lagoon suitable for a fleet anchorage. The largest island in the group is Babelthuap at 10 by 16 miles. Hilly and densely forested, its highest elevation is 794 feet. An airfield was built near the southeast end. Scores of small islands stretch from the southwest of Babelthuap. Among these are Koror Island, home of the Palaus’ administrative center, naval headquarters, and a submarine base. Another submarine base and a seaplane base were on neighboring Arakabesan Island.

Peleliu Island is 25 miles southwest of Babelthuap. The Japanese called it Periryu and the Allied codename was “Earthenware.” An extremely irregular-shaped island, Peleliu has been likened to a lobster’s claw. From its northeast end to its southwest it is approximately 6 miles long and slightly over 2 miles wide in the south. That area is relatively low and flat and the Japanese built a fully developed X-shaped naval airfield there. Good landing beaches, fronted by a reef up to 1,600 yards wide, lie on the west shore. Most of the deeply indented southeast shore is lined with dense mangrove swamps, shallow bays, and a fringing reef. A few small, low islands lie offshore. A 3,500-yard long, approximately 1,000-yard wide peninsula runs to the northeast with a wide reef on the island’s northwest side. In 1944 roads followed the shores on both sides of the peninsula. Low, flat, scrub tree-covered Ngesebus and Kongauru Islands lie off the end of the peninsula. Ngesebus was connected to the northeast end of the peninsula by a 600-yard timber causeway and a 100-yard causeway connected Kongauru to Ngesebus. A 60cm (24in.) narrow-gauge railroad crossed the 600-yard causeway. The Japanese were constructing an airstrip on Ngesebus. More small islands, called the Northern Islands by the Americans, were scattered to the northeast of Ngesebus and Kongauru.

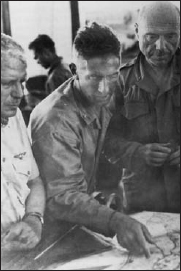

Col Harry D. “Bucky” Harris, Commander, 5th Marines, seen here on Peleliu conferring with MajGen Roy S. Geiger, Commanding General, IIIAC (left), and William H. Rupertus, Commanding General, 1st Mar. Div. (right), prior to 5th Marines operations in northern Peleliu.

The southern end of Peleliu and its eastern peninsula are low, fairly level, and mostly covered by brush and scrub trees. The beaches where the Marine landing occurred were covered with coconut palms. North of the airfield and approximately one-third the way up the northeast peninsula are the Umurbrogol Mountains. These are extremely rugged raised coral and limestone hills and ridges honeycombed with outcroppings, gorges, crags, sinkholes, and caves. Faced with cliffs up to 60ft high, they rose to 550ft above sea level. The low “mountains” were covered with dense forests and US intelligence had no idea of how chaotic the terrain was beneath them and even assessed them as being low rolling hills. The Japanese turned these craggy terrain features into fortifications and built scores of concrete pillboxes and bunkers providing interlocking fields of fire and mutual support. Virtually every cave was turned into a strongpoint and often interconnected to others by tunnels. It proved to be impossible to attack one position without coming under fire from two or more other positions. Most of the vegetation in the area was blown away during the weeks of the battle. It proved to be an attacker’s nightmare and a defender’s dream.

Col Herman H. (“hard headed”) Hanneken, Commander 7th Marines. Veteran of pre-war campaigns in Haiti and Nicaragua and had served as an enlisted Marine during WW1 and in October of 1919 as a captain in the Haitan Gendarmerie, earning himself the Medal of Honor for almost single-handedly killing a Cacos guerilla leader. Hanneken had served as Chief of Staff and Assistant Division Commander, 1st Mar. Div., prior to being given command of the 7th Marines in February 1944.

The Umurbrogol Mountains stretched part-way up the northeast peninsula and then tapered out into separate limestone ridges and hills of the Kamilianlul and Amiangal Mountains, all densely covered by forest. These too would have to be cleared, but did not pose the obstacle that the Umurbrogol Mountains did. They retained much of their vegetation through the battle although it was blasted clear in some areas.

Beside the airfield, the Japanese had built hangars, support facilities, administrative buildings, barracks, and warehouses. There was also a radio direction finder station north of the airfield and near the end of the northeast peninsula was a radio station and a phosphate processing plant – the island’s main commercial value. Most of these buildings were made of reinforced concrete, but for the most part were destroyed during the battle. The peninsula had a narrow-gauge railroad system to haul phosphate.

The 81st Inf. Div.’s objective, Angaur Island, is 7 miles to the southwest of Peleliu and the southernmost of the Palaus. The Japanese called it Angsuru and the Allied codename was “Domestic.” Angaur is 2½ miles across north to south and 1½ miles wide across the center. It is covered mainly by gently rolling terrain, but the northeast portion consists of extremely rugged and jagged coral outcroppings and limestone ridges up to 200ft in elevation. From this area was mined phosphate. Saipan Town and the phosphate plant were on the west central coast. An extensive narrow-gauge railroad system served the northern and central portions of the island. Much of it had been pulled up though to build fortifications. Most of the island was covered with scrub brush although the center was heavily wooded. A few small lakes and swamps were scattered about the island. There were no permanent military installations on the island other than the Japanese defenses.

So, the stage was set for one of the most controversial campaigns of the Pacific War and one of the bloodiest battles in US Marine Corps history.

A few words on pronunciation. Pelau is pronounced “Pelew” and Peleliu is “Pel-la-lew.” Numerous place names begin with “Ng,” unique to the local native blend of Polynesian and Melanesian. Americans tended to pronounce this as a syllable, “Neg,” as in “Negesbus” for Ngesebus Island, but a closer approximation is “N’y” as “N’yesbus.” Umurbrogol is pronounced approximately “Um-er-bro-gol.”