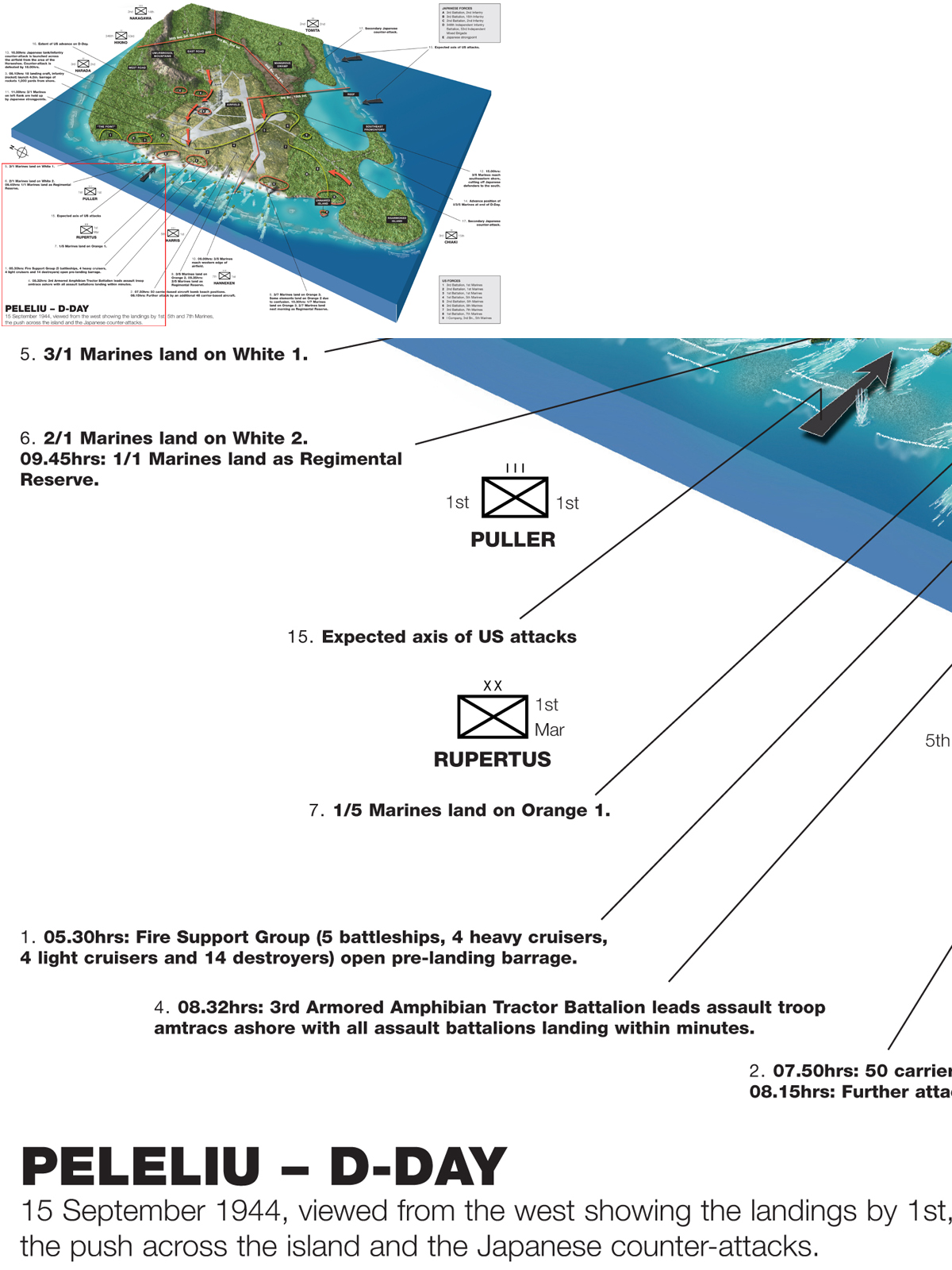

15 September 1944 – D-Day on Peleliu. After an uneventful 2,100-mile voyage from their practice landings on Guadalcanal, men of the 1st Mar. Div. and the 81st Inf. Div. prepared for battle. In the pre-dawn light, on board troop transports, men checked and re-checked weapons and equipment. Breakfast of steak and eggs was a tradition that was often regretted by many a marine as he churned towards the beach in an amtrac or flat-bottomed Higgins boat – and cursed by many a ship’s surgeon as he operated on the wounded. They climbed into LCVPs (Landing Craft, Vehicle and Personnel or “Higgins boat,” after its inventor Andrew Higgins) and LVTs (Landing Vehicle, Tracked – better known as amphibian tractors or “amtracs”).

Practice landings had demonstrated shortcomings, including troops hurriedly loaded onto wrong transports who had to be swapped over at sea. Above all, the area chosen for the practice landings did not have a fringing reef, so the often hazardous task of transferring from landing craft to amtrac could only be simulated and in no way demonstrated the rough sea conditions at a reef’s edge. The practice landings resulted in several casualties from broken bones, including the Commanding General, 1st Mar. Div., MajGen Rupertus, with a broken ankle.

Starting three days earlier (12 September), frogmen of Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT) 6 and 7 began clearing submerged obstructions and blasting pathways through the reef for the assault troops. UDT 8 was doing the same at Angaur. This dangerous work was often carried out under direct small arms fire from the Japanese defending troops on the beaches. The Kossol Passage north of Babelthuap was swept for mines resulting in the loss of a minesweeper; a destroyer and another minesweeper were damaged in the effort.

A wrecked DUKW lies totally destroyed on the beach after hitting one of the multitude of mines sown by Nakagawa’s men on practically all potential landing sites. The resistance was far fiercer and vehicle losses higher than the Marines had expected.

7th Marines CP established in a large Japanese tank trap just inland from Beach Orange. This later became General Rupertus’s first CP upon his landing on D+1.

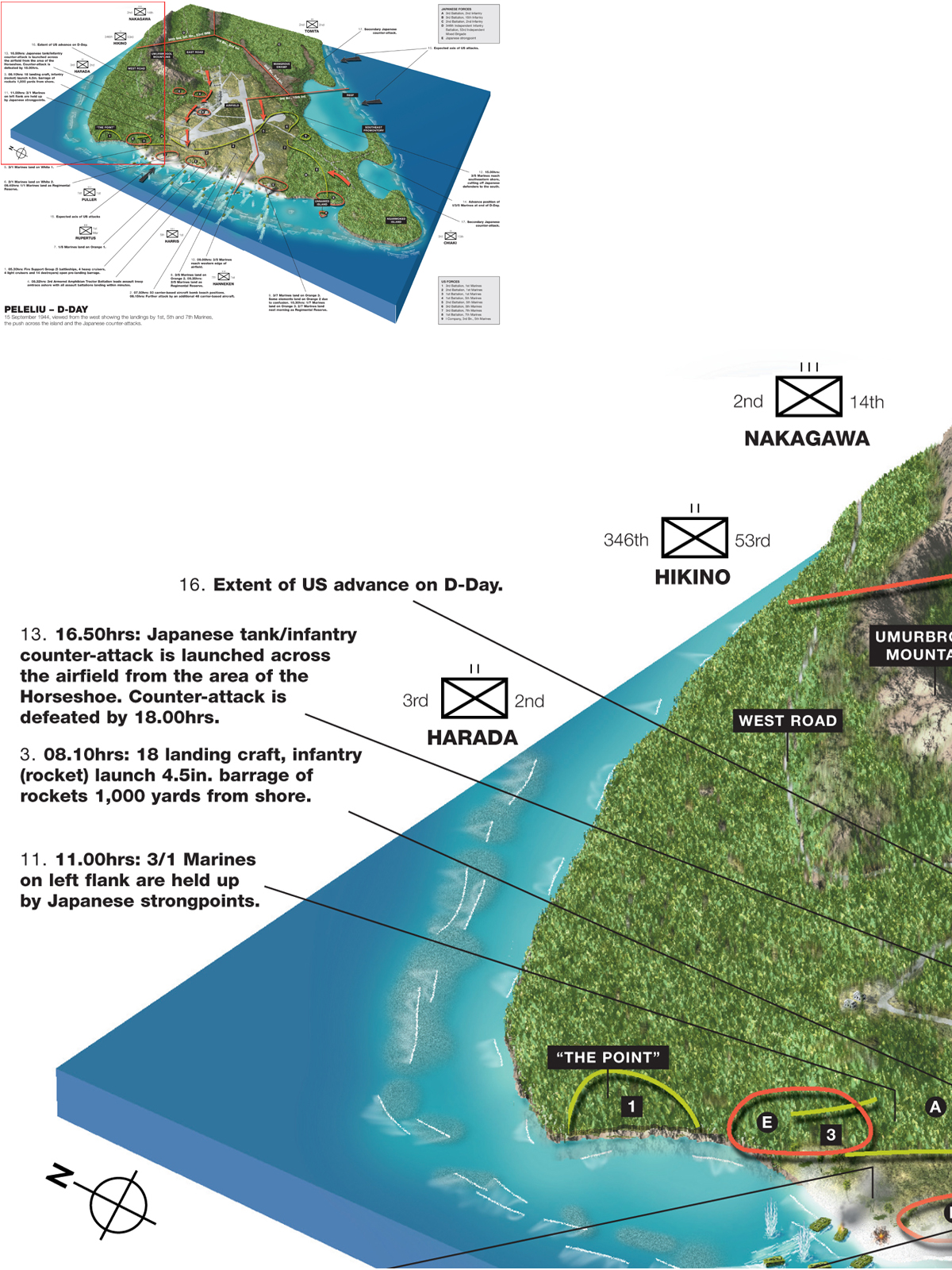

At 0530hrs naval support ships had begun the pre-landing bombardment of the beaches from a range of 1,000 yards. This lifted at 0750hrs to make way for carrier-borne aircraft to strafe the beaches in front of the first landing waves, whilst the naval bombardment moved to targets inland. White phosphorous smoke shells were fired to screen the assault waves from the Japanese on the high ground inland to the north of the airfield.

The plan called for the first assault waves to be in amtracs. Subsequent support waves would transfer at the reef’s edge from LCVPs to amtracs, returning from the beaches. This was basically the same plan as at Tarawa in 1943, and more than one marine had thoughts of their comrades in the 2nd Mar. Div. wading several hundred yards under murderous fire to the beaches when insufficient numbers of amtracs survived the return trip. This time, however, the first waves would be preceded by armored LVTs, which were specially produced amtracs with additional armor and a turreted 37mm gun, LVT(A)1, or 75mm howitzer LVT(A)4 to act as amphibious tanks to suppress beach defenses for the initial assault waves.

Preceding the first assault waves were 18 landing craft, infantry (gun) (LCI(G)) equipped with 4.5in. rocket launchers. Each of these fired a salvo of 72 rockets onto the beaches. When the third assault wave passed them, they retired to the flanks to deliver “on call” fire. In addition, four landing craft, infantry (mortar) (LCI[M])s armed with three 4.2in. mortars, stood off the northern portion of Beach White to fire continuous salvos onto the area inland of the beach.

Admiral Oldendorf’s confidence in his pre-assault bombardment proved misplaced. As the LVTs crossed the line of departure and raced for the beaches, it soon became apparent that there were still plenty of live Japanese on Peleliu. Artillery and mortar fire began to fall amongst the amtracs, several receiving direct hits; 26 were destroyed on D-Day. Smoke from the Japanese fire and burning amtracs, combined with the drifting smokescreen, completely obscured the beachhead for some time from the following assault waves and the transports off-shore.

An individual marine’s account of what followed paints an almost surreal picture of how young men respond to the unprecedented fierceness of assaulting a well-defended beach.

Sterling Mace was a BAR-man in Company K, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines (K/3/5). He was in one of the first waves to go in on Beach Orange 2. Twenty years after D-Day, he wrote:

“Into the ship’s hold we descended to find the amphibian tractors waiting with their diesel engines roaring. The sound was deafening. The smell of the acrid fumes was sickening. The noise of the engines, men and equipment reverberated off the steel hull. We huddled, thirty-six men and a 37mm field piece to a tractor, waiting for the bow doors to open. Suddenly, the doors opened wide letting the dawn’s light shed on us. Out the bay doors poured the ‘Alligators,’ which was a nickname for the amphibian tractors. One after another they splashed into the sea and, in full throttle, left the LST behind in its wake. I couldn’t give you a count on the amount as I was not in a position to look over the bulkhead of the tractor I was in. We were jammed elbow to elbow. Not to mention the rise and fall in the waves. It seemed as if the ‘Alligators’ were like rubber balls bobbing up and down in the ocean swells. As we rode up one crest I caught a glimpse of several sailors on board the LST drinking from coffee mugs and watching us depart. I thought, then, maybe I was in the wrong service. But looking at the faces of my buddies around me, I had mixed emotions. We had come so far together. I knew them. And to see their expressions of concern for themselves and each other, I was proud to be alongside of these men. Some were dead serious with furrows across their brows. Some were laughing and nervously joking. However, if the tractor made an uncommonly groan or hit a high peak of an underwater coral reef, the look of borderline panic would flush their faces.

Seabees with heavy construction equipment intended for reconstructing the airfield on Peleliu first spend time clearing the beaches of debris and disabled LVTs and DUKWs. In addition to all their sophisticated weaponry the Marines also made use of some very simple technology such as the two-man handcart shown here, used by the US Marines since before WWI.

Aftermath of the Japanese armored counterattack on the afternoon of D-Day. The light Japanese Type 95 Ha-Go tanks were no match for the Marine artillery, anti-tank guns and particularly the Shermans. The Marines also had half-track-mounted 105mm guns, which were particularly useful against fixed defenses such as bunkers and pillboxes as well as tanks.

“The amphibians began to circle and gradually drawing closer to the island. The beach master was organizing the numerical order of the tractors for the different waves to land and follow the battle plan. The 1st Marines was to land on our left. While the 7th [Marines] would be on our right. The 5th [Marines] would head straight, hitting Orange Beach 2. The beach was a little stretch of white sand with a backdrop of solid black smoke hiding the silhouette of tropical terrain of trees and mountains.

“Off in the distance a flag is waved and the amphibians turn their course toward the shore. Some 500 yards off shore were a line of LCIs launching 12,000 rockets onto the beach. The great battleships on the horizon are, also, firing away at the island. Someone in the outfit notices the tractor is fifteen yards in front of the main wave. Which brings about a chorus of ‘Slow down! You’re going too fast.’ Nervous laughter.

“There comes the sound of grating sand and coral from the bottom of the tractor. The rear door drops down and we exit. One after another we step out, turn to the right or left to run toward the beach…”

Mace’s feelings were typical of many Marines on D-Day.

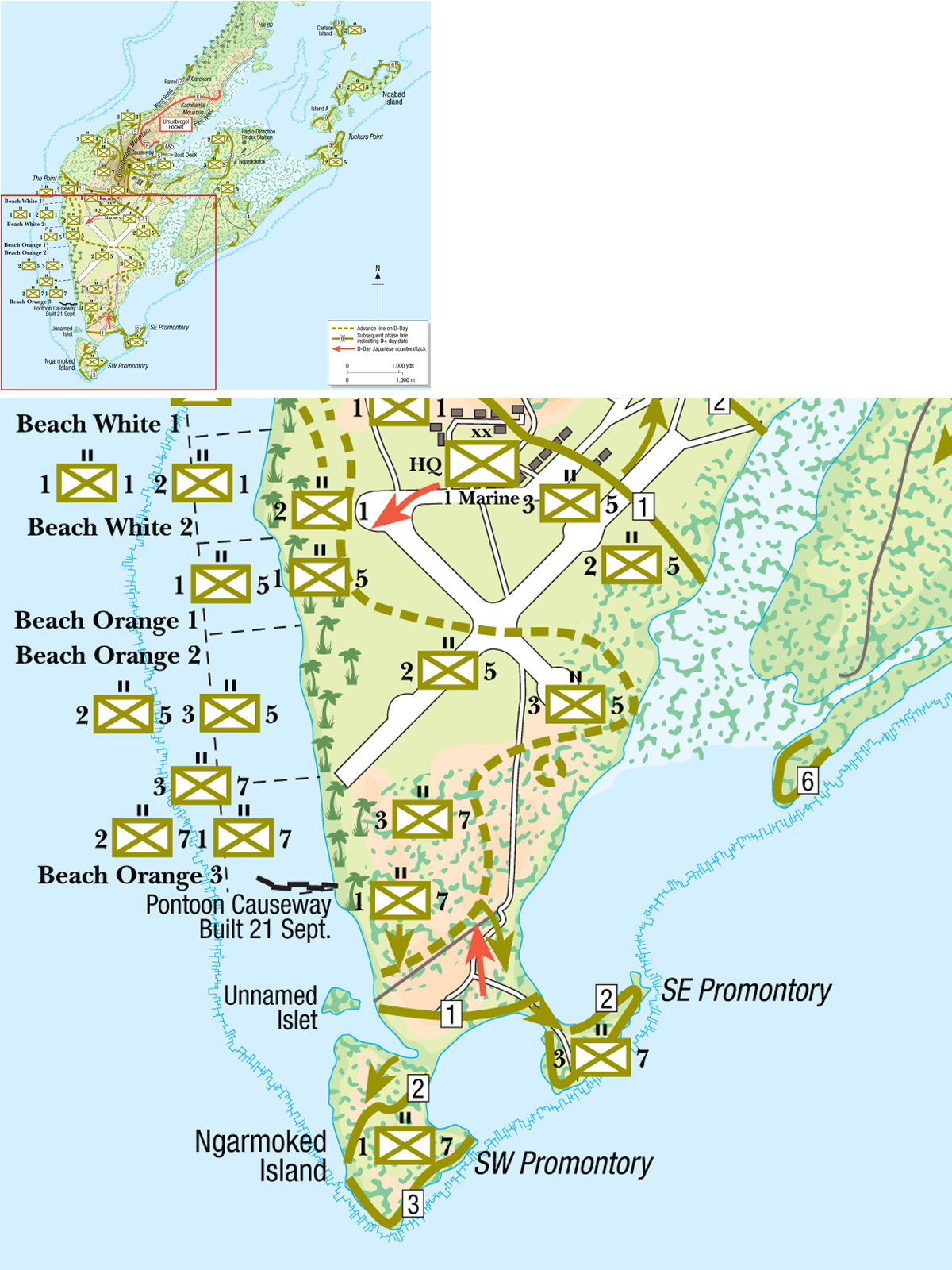

The first Marines to hit the beaches were men of the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines (3/1). They landed on Beach White 1 at 0832hrs, just 2 minutes behind schedule, and within the next 4 minutes there were Marines on all five landing beaches.

On Beach White the 1st Marines landed as planned, with the 2nd Battalion on the right and the 3rd on the left, with the 1st Battalion scheduled to land at approximately 0945hrs as regimental reserve.

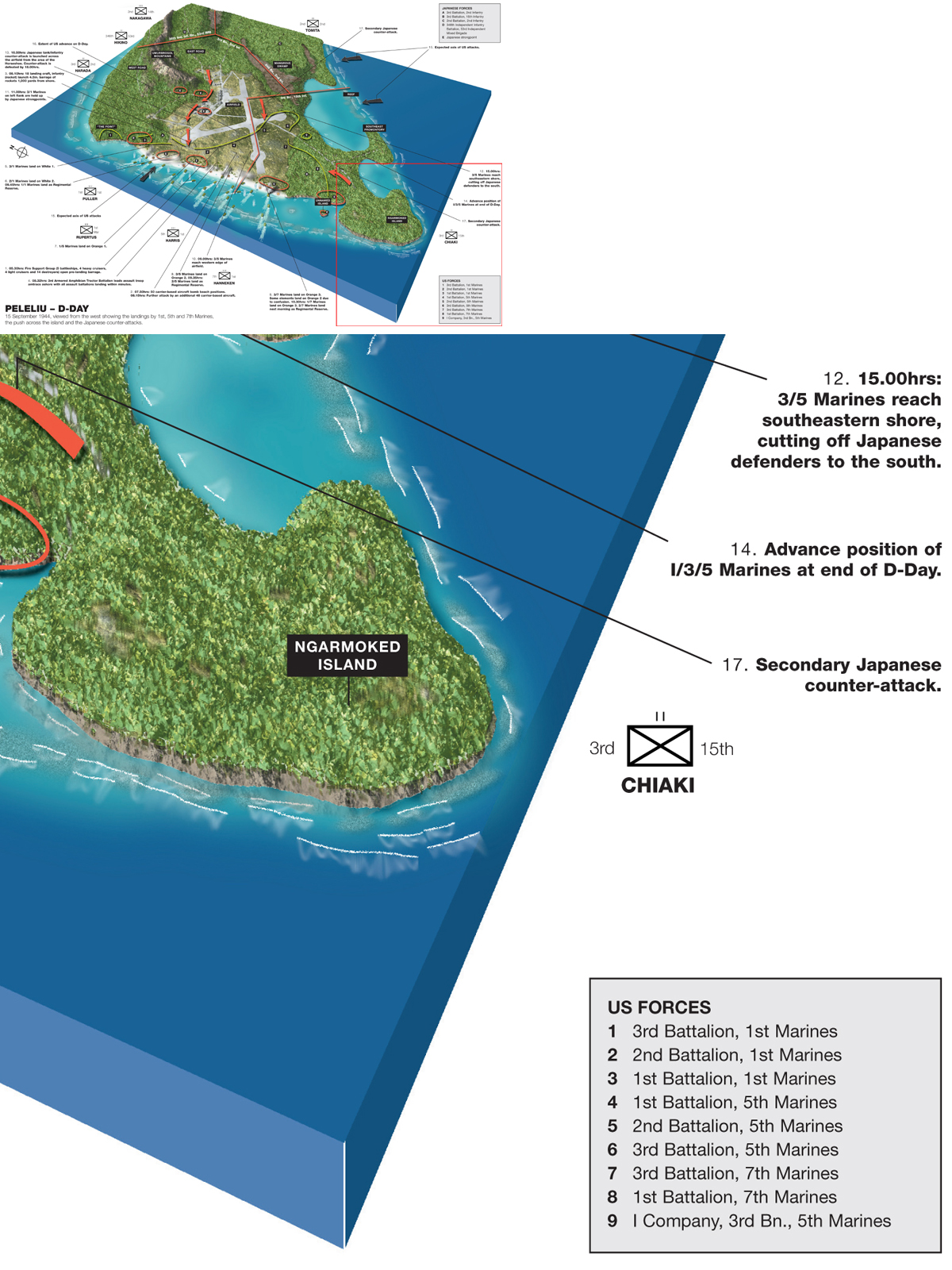

BEACH ORANGE 3, 08.34HRS, D-DAY (pages 46–47)

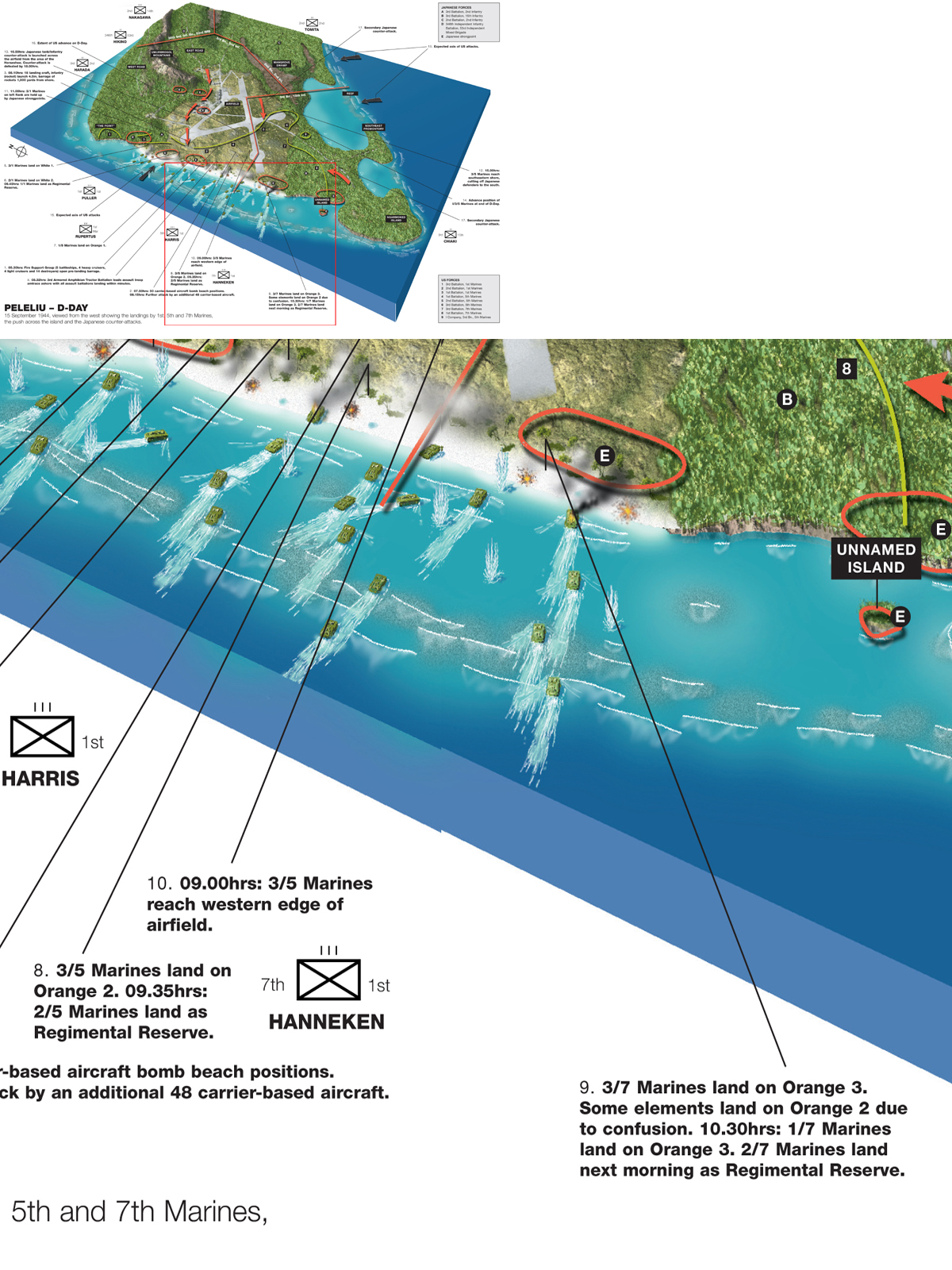

On the extreme right flank of the beachhead, the 7th Marines came ashore in a column of battalions with 3rd in the lead. This battalion bore the full brunt of machine gun, antiboat gun, and mortar fire enfilading the beach from Unnamed and Ngarmoked Islands on Peleliu’s south tip. LVT(4) amphibian tractors (1) were essential in delivering troops ashore as they carried more personnel than the earlier LVT(2)s, although these were used as well because of the shortages of LVT(4)s. This allowed five battalions to be landed by the first waves. The LVT(4) was the first LVT provided with a ramp. The firing wires for scores of command-detonated aerial bombs planted on the ½-mile wide reef had been cut by the bombardment sparing many amtracs. Indirect fire had inflicted little damage on the amtracs, but as they neared the beach large-caliber automatic weapons (13.2mm, 20mm, 25mm) and antiboat guns began to take their toll. 26 LVTs were knocked out on the first day with dozens damaged. As the LVTs came ashore the troops shoved ammunition boxes (2) and water cans (3) over the sides. These were to be picked up later by litter-bearers returning to the frontline after evacuating casualties. Two deficiencies encountered by the Marines on Peleliu were insufficient replacement combat troops and inadequate medical support. One reason for this is that it was expected that the island would be secured within five days. What was available was stretched to support the Marines’ 44-day fight. Only two approximately 150-man replacement companies were deployed. They were attached to the 1st Pioneer Battalion as Companies D and E to assist with unloading until D+3 (9 September) when they were released as replacements to the regiments. They proved inadequate to replace the losses suffered by that date. Company C, 1st Tank Battalion deployed without its tanks and served as replacement crews. No more replacements were forthcoming for the remainder of battle. This forced the relief of the 1st Marines on D+16 (22 September) by the Army’s 321st Infantry and the relief of the 1st Mar. Div. by the 81st Inf. Div. between 15 and 20 October. Two approximately 1,350-man replacement drafts were later attached to each Marine division landing on Iwo Jima and Okinawa, but even these proved inadequate. The Division relied on organic medical support. Each infantry battalion possessed a two-officer, 42-enlisted man aid station manned by Navy personnel. Medical corpsmen (4) from this element were attached to rifle platoons and also operated small rifle company aid stations. The infantry regiments each had an aid station with five officers and 19 enlisted men. While mostly Navy personnel, it had five Marine drivers for the ¼-ton jeep ambulances. A 102-man medical company was attached to each combat team for additional support, which in-turn attached a clearing section to each battalion to support the aid station. Company B, 1st Motor Transport Battalion deployed without its vehicles to serve as litter bearers and a 29-man band section was attached to each combat team for the same purpose. There were no higher echelon medical units ashore. Casualties were evacuated to troop transports by landing craft and amtrac. Well-equipped surgical hospitals were operated aboard these ships. (Howard Gerrard)

The exact numbers of tanks involved in the attack is uncertain, probably between 13 and 17. It is said that in the aftermath there were not enough pieces of some of the Japanese tanks left to make an accurate count possible.

On White 2, the 2/1 landed successfully and proceeded to push inland against Japanese resistance described in their after-action report as “moderate.” The 2/1 advanced, supported by some of the armored LVTs until their M4A2 Sherman tanks could get ashore, to reach a line approximately 350 yards inland through heavy woods by 0930hrs. Their hour’s progress was not without casualties. Here 2/1 halted, at the far side of the woods and facing the airfield and buildings area. Tying in with the 5th Marines on their right flank, they held pending a solution to the problems the 3/1 were facing.

As soon as 3/1 hit Beach White 1, they faced stubborn and violent opposition from strongly emplaced Japanese small arms fire to their immediate front, as well as from artillery and mortar fire that was blanketing the whole beach area. To make matters worse, no sooner had the lead elements of 3/1 landed and advanced less than 100 yards inland, than they found themselves confronted by a most formidable natural obstacle, a rugged coral ridge, some 30ft high. This had not shown up on any maps. Worse, the face of this ridge (christened “The Point” by the Marines) was honeycombed with caves and firing positions which the Japanese had blasted into the coral and had turned into excellent defensive positions which resisted all initial assaults. Even after tanks arrived to support the assault troops attempting to storm the northern portion of the ridge, they stumbled into a wide, deep anti-tank ditch, dominated by the ridge itself. Here they came under severe and accurate enfilading fire and were pinned down for hours.

A/1/1 of the regimental reserve battalion was committed early in the day to support 3/1, followed by B/1/1 late in the afternoon. Still, all efforts failed to close the gap which had developed on the left. Late in the afternoon, a foothold was gained on the southern area of the point, which improved the situation somewhat. But the situation still gave great cause for concern, compounded by the fact that five LVTs carrying the 1st Marines command group had been badly hit whilst crossing the reef, with resultant loss of communications equipment and operators. Only much later in the day did divisional command become fully aware of the precariousness of the 1st Marines’ position.

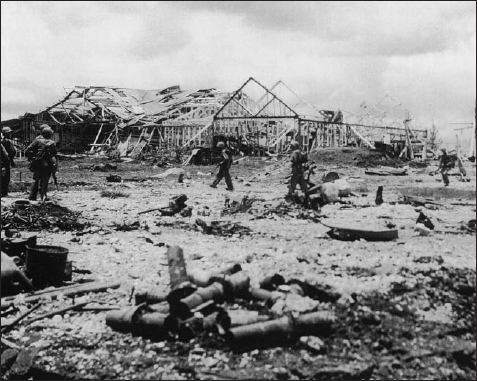

Marines among the ruins of the barracks area on the edge of the airfield. Not much was left of the buildings after the pre-landing bombardment, but the runways themselves were not targeted and remain relatively unscathed.

After more than eight hours of possibly the most fierce fighting of the Pacific War so far, two gaps in the 1st Marines’ lines were so serious as to endanger the entire Division’s position on D-Day. Indeed, so precarious was the situation that all possible reserves were committed, including headquarters personnel and at least 100 men from the 1st Engineer Battalion. Together they formed a defense in depth against the threat of a Japanese counterattack that could possibly roll up the entire line and sweep down the now congested landing beaches. Fortunately for the Marines, no such counterattack was planned by the Japanese.

It became apparent to the Marines that The Point was unassailable from the front and so eventually units fought inland and assaulted The Point from the rear. These units, commanded by Capt George P. Hunt, fought their way along The Point for nearly two hours, during which time they succeeded in neutralizing all of the enemy infantry protecting the major defensive blockhouses and pill boxes. The principal defense installation was a reinforced concrete casement built into the coral, mounting a 25mm automatic cannon, which had been raking the assault beaches all morning. This blockhouse was taken from above by Lieutenant William L. Willis, who dropped a smoke grenade outside the blockhouse’s embrasure, to cover the approach of his men, and Corporal Anderson who launched a rifle grenade through the firing aperture. This disabled the gun and ignited the ammunition inside the blockhouse. After a huge explosion, the fleeing Japanese defenders were mown down by waiting Marine riflemen.

Capt Hunt and his surviving 30 or so men would remain isolated on The Point for the next 30 hours, all the time under attack from Japanese infiltrators trying to take advantage of the gap in Company K’s lines. When relieved, Hunt only had 18 men standing to defend The Point and Company K had in total only 78 men remaining out of 235.

In the center, on beaches Orange 1 and 2, the 5th Marines fared a little better. The deadly antiboat fire on the way in had been less effective than elsewhere, though they too suffered losses in assault boats and amtracs from artillery and mortar fire.

1/5 landed on Orange 1 and 3/5 on Orange 2. On both beaches they met only scattered resistance, and little more as they moved inland. Instead of the unmapped coral ridges faced by the 1st Marines, the 5th Marines advanced through coconut groves which afforded ample cover, reaching their first objective line and tying in with 2/1 on the left by 0930hrs in front of the airfield.

A bizarre detail of Orange 2 was recalled by Sterling Mace:

“There, as we’re heading towards shore, a small dog is wagging its tail and barking at us. The sound of the dog’s bark is suddenly unheard as the tractor’s gunner opens fire. His fifty caliber machine gun blazing away at the vegetation along the beachfront. The last time we saw the dog, the little guy was in a mad dash down the beach…

“In the time it took from the amphibian tractor in the surf to the beach everything was in mass confusion.”

Here, 1/5 halted. Partly, this was because of the lack of progress by the 1st Marines on the extreme left against The Point, and partly due to the murderous Japanese artillery and mortar fire which was sweeping the airfield and open ground to their immediate front.

On Orange 2, 3/5 did not fare as well as 1/5 on Orange 1. Lieutenant Colonel Austin C. Shoftner, commander of 3/5, lost his executive officer Major Robert Ash within minutes of landing, killed by Japanese artillery fire. The LVT carrying most of the battalion’s communications equipment and personnel was also destroyed on the reef.

According to plan, Company I landed on the left and Company K on the right, with Company L landing shortly afterwards as battalion reserve. On the left, all went comparatively well with Company I making contact with 1/5 and advancing inland along with them.

On the right however, Company K ran into difficulties when elements of the 7th Marines landed on beach Orange 2 instead of landing on their intended beach of Orange 3. This caused some confusion on the beach and delayed Company K’s advance. They did not draw abreast of Company I until 1000hrs.

The 3rd Battalion’s situation deteriorated somewhat after the advance inland was resumed at 1030hrs. Company K advanced through fairly dense scrub which provided concealment from the Japanese shelling. As a result they began to pull ahead of Company I and eventually broke contact with them. Company L was committed in an effort to close the gap, but this line remained dangerously extended for most of D-Day. By the afternoon, the regimental reserve, 2/5, had landed and it relieved Company I who in turn were ordered to pass around Company L and tie in with them and Company K. Easier ordered than done as there was some confusion due to the poor quality of the maps of that area.

More bad luck befell the 3rd Battalion when, at about 1700hrs, a Japanese mortar barrage struck the command post. Colonel Shofner and several other members of the command staff were wounded and had to be evacuated, which severely disrupted the effectiveness of the 3rd Battalion as a unit.

Lieutenant Colonel Lewis W. Walt, executive officer of the 5th Marines, assumed command of the 3rd Battalion, but it was after dark before he located even the first of his companies. It would take him all night to restore any semblance of order in the 3rd Battalion.

By the end of D-Day, the front of the 5th Marines presented a rather odd appearance with the three Battalions facing east, north and south and the 2nd and 3rd Battalions virtually back to back, but strange as this seemed they were well enough integrated to present more than adequate defense for the night.

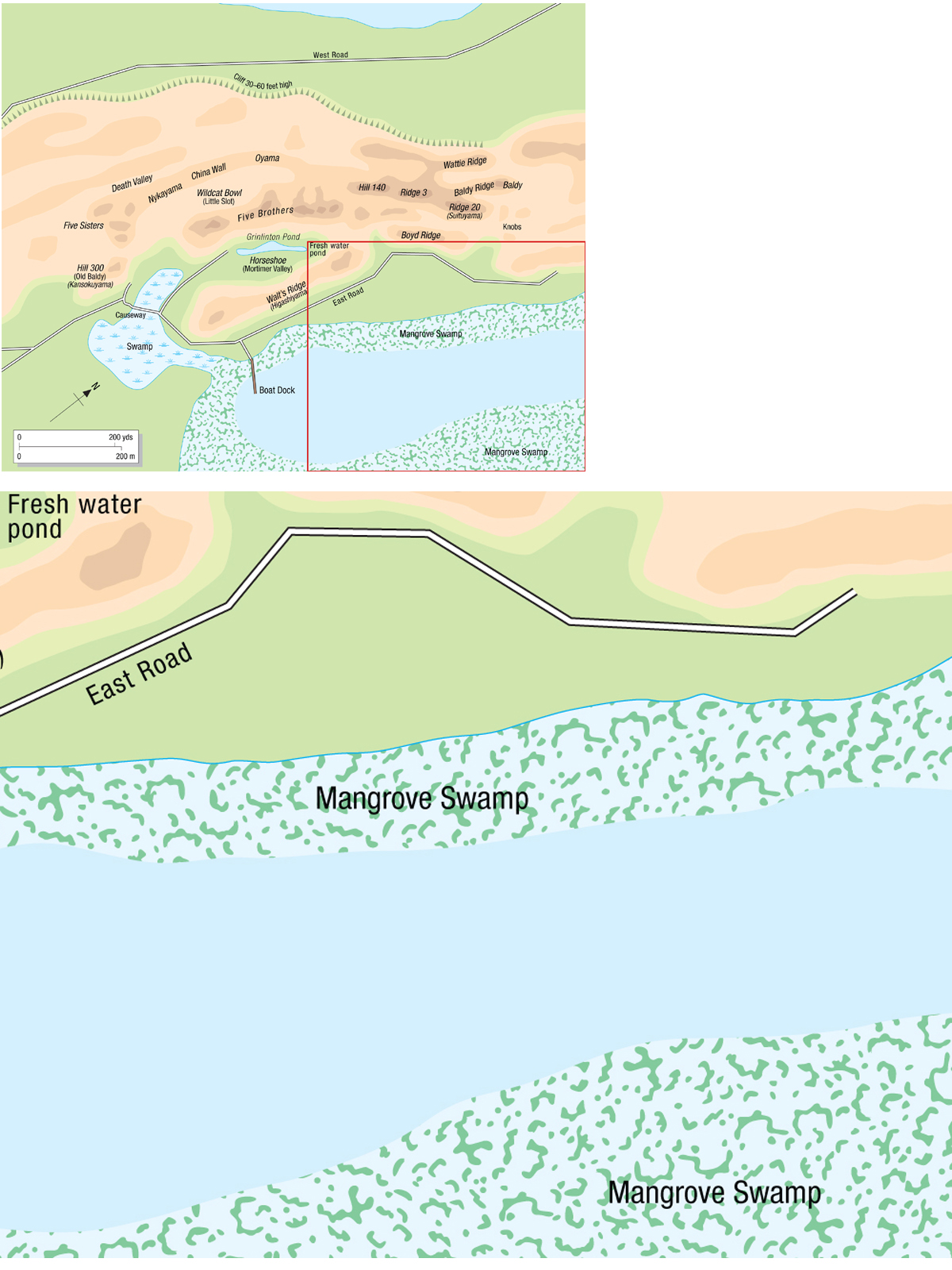

On the extreme right the 7th Marines were to land on Beach Orange 3 with two battalions in column. The third battalion, 2/7, was kept afloat as the divisional reserve.

The 3rd Battalion landed first. The 1st Battalion was to land shortly afterwards, but they encountered serious difficulties. The reef off Orange 3 was so cluttered with natural and man-made obstacles that the amtracs ended up approaching the beach in column, thus slowing the attack and also making them prime targets for Japanese antiboat fire, which was poured into them from Ngarmoked Island on the southwest of the landing beaches, in addition to the heavy artillery and mortar fire from inland on Peleliu.

This situation caused many amtrac drivers to veer off to the left, resulting in them landing on Orange 2 instead of Orange 3, creating the confusion experienced by 3/5. Extricating 3/7 was further complicated by land mines and barbed wire entanglements, so much valuable time was lost in getting the 7th Marines back on course. The 3/11 lost an entire 105mm battery on D-Day and was forced to re-embark and land again the next day as its firing positions were still in enemy hands.

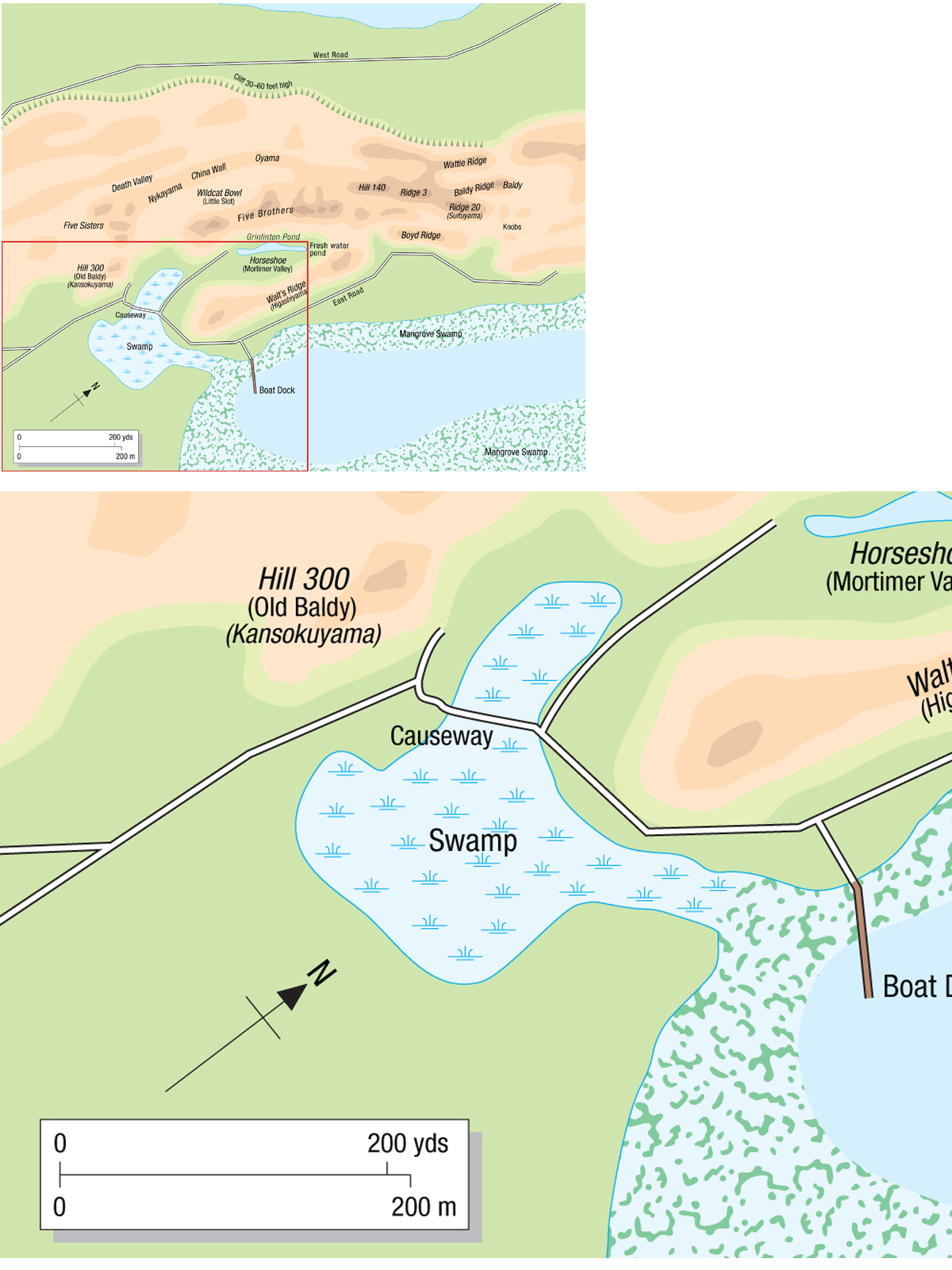

Once again, as with the 1st Marines, there was a substantial obstacle in front of the 7th Marines that was not on any maps. This time, however, it would prove most useful. This obstacle took the form of a large anti-tank ditch just a short distance inland of Orange 3. It had only been spotted by the pilot of one of the planes observing the landings, who flashed a report back to Divisional HQ. The ditch proved most useful for moving troops forward in relative safety and provided a superb instant dugout for the battalion command post (CP).

The 3rd Battalion advanced inland, with Company K on the right and Company I on the left, and linked up with 3/5 advancing inland from Orange 2.

By 1045hrs Company K’s advance had covered some 500 yards and they had also captured a Japanese radio direction finder in the process. Company I on the other hand had run into stiff Japanese resistance and were halted by a complex of blockhouses and gun emplacements in the ruins of the Japanese barracks area. Here Company I halted to await the arrival of tank support. This tank support became somewhat confused by an unexpected coincidence: the flank battalions of the two assaulting regiments in the center and right were both the 3rd (3/5 and 3/7) with both containing Companies I, K, and L. The unfortunate tank commanders looking for 3/7 who had wandered into 3/5 area due to obstacles – in particular the large antitank ditch on Orange 3 – enquired of a body of troops they encountered “is this Company I, 3rd Battalion?” Hearing the right answer in the wrong place, they proceeded to operate with these troops, who were in fact Company I of 3/5 and not Company I of 3/7. Happily, this was one of those confusions of battle that helped more than it hindered.

M4A2 Sherman tanks advance across the airfield supporting the main advance to the south and east. In the background can be seen the Japanese aircraft hangars.

The confusion resulted in a gap between the two regiments as 3/7 paused to take stock of the situation, whereas 3/5 was actually pushing ahead. In an effort to re-establish contact with 3/5, Company L worked patrols further and further to the left until its foremost patrol emerged on the southern edge of the airfield. This was completely out of its regimental zone of action and several hundred yards to the rear of the units it was looking for.

In the meantime, 1/7 had landed as planned on Orange 3 at 1030hrs with slightly more success than 3/7, although some elements still ended up on Orange 2. Resistance was initially described as “light,” but when the Battalion wheeled right as per plan, Japanese resistance increased notably. Once again poor maps let the Marines down. This time a dense swamp, not shown on any map, confronted the right half of the battalion and the only trail round it was heavily defended. It took considerable time to work around the swamp and it was not until 1520hrs that Col Gormley was able to confirm reaching his objective line. During the night the battalion would receive a strong Japanese counter-attack from the swamp, which was defeated only with the aid of Black Marine shore party personnel who volunteered as riflemen.

The lack of progress on the right worried General Rupertus aboard the USS Du Page (APA-41) and his concern over the loss of momentum resulted in him first committing the divisional reconnaissance company ashore and later still attempting to commit the divisional reserve.

Gains for the Marines on D-Day were disappointing compared to the optimistic predictions. The 1st and 5th Marines had fallen short of their targets and the 7th Marines were the only ones to make any reasonable progress inland. The gap that remained in the middle of 3/5 on the left posed a threat to the entire south facing line.

JAPANESE TANK COUNTER-ATTACK, 16.50HRS, D-DAY (pages 54–55)

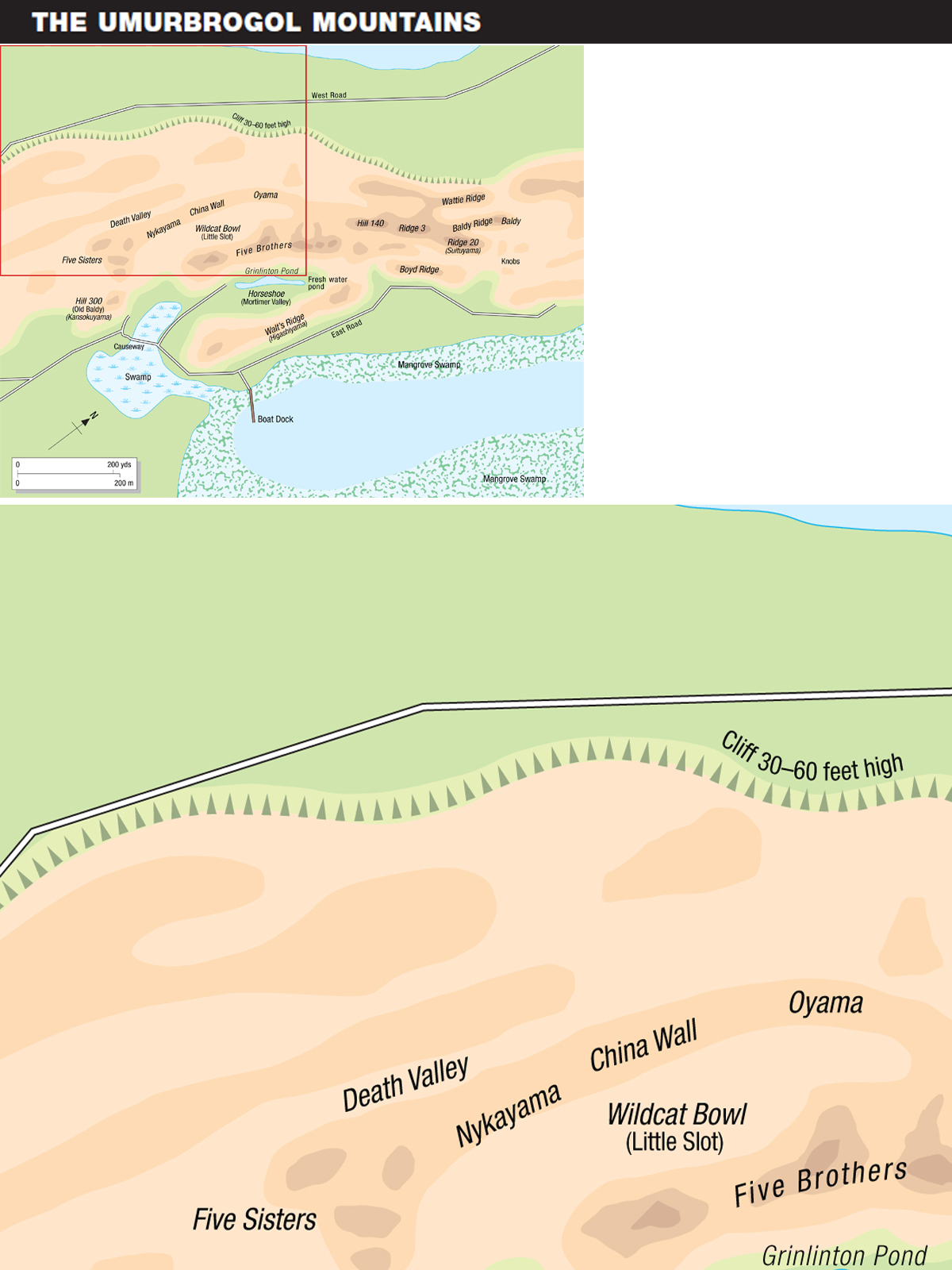

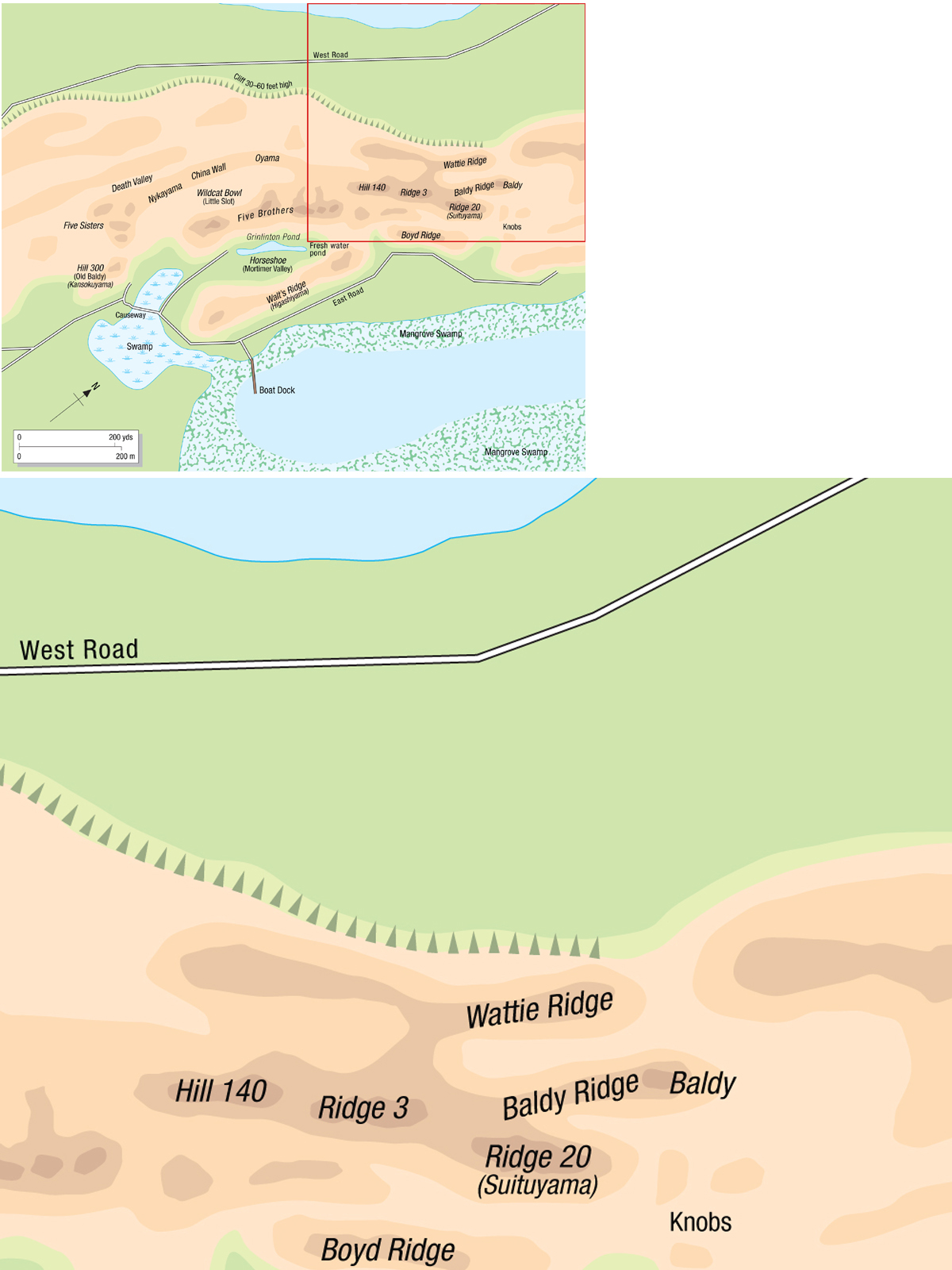

The expected Japanese counter-attack on the landing force was launched from north of the airfield, the area in the southeast portion of the Umubrogol Mountains that would become known as the Horseshoe. A rifle company of 1st Battalion, 2nd Infantry and the 14th Division Tank Company launched the Japanese attack towards 1st Battalion, 5th Marines. The Japanese tanks raced ahead of their supporting infantry, although some infantrymen (1) were unfortunate enough to ride on the back of tanks – some tanks had been fitted with bamboo handrails on the engine deck for the riflemen to cling to. The attack was doomed from the start as it was executed too late. This was an error the Japanese frequently made; rather than attacking into the first assault waves as they landed on the beaches under heavy fire and were still disorganized, the Japanese waited until the Americans had tanks ashore along with more troops and had consolidated. On Peleliu Marine tanks had already been landed and were in position waiting. An extremely confused battle erupted as the Japanese tanks charged across the airfield. Their sheer momentum carried a few through the Marine line and into the rear, but Marine casualties were very light. All but two Japanese tanks were destroyed as eight M4A2 Sherman tanks (2) of Companies A and B, 1st Tank Battalion joined the fray. At least half of the Japanese infantry was wiped out in this poorly coordinated attack. It has never been accurately determined how many Japanese tanks were destroyed, but reports indicate between 11 and 17. By totaling the claims of Japanese tanks killed in unit after action reports, one Marine staff officer calculated that 179½ tanks had been knocked out. The Type 95 (1935) Ha-Go light tanks (3) were vulnerable to virtually all Marine weapons over .30cal having only 6–12mm (0.24 to 0.47in.) of armor. Armed with the 37mm Type 94 (1934) gun (4), the tank also mounted a 7.7mm Type 97 (1937) machine gun in the left bow of the hull (5) and another in the rear of the turret. It carried 130 high explosive and armor-piercing-high explosive rounds plus 2,970 rounds of 7.7mm in 30-round magazines. The Type 95 was one of the most numerous tanks produced by Japan. While much an improvement over the Type 93 (1933), this 10-ton tank’s capabilities and design fell far short of contemporary US and European light tanks. One of its main problems was the one-man turret, which left the tank commander to observe for enemy activity in all directions, determine his route, maintain his place in the formation, watch the platoon or company commander’s tank for signals, load and fire the main gun and the rear machine gun, and direct the driver and bow machine-gunner. The short-barreled 37mm gun was of comparatively low velocity and lacked the armor penetration of US 37mm guns. Even though they had the same designation, its ammunition was not interchangeable with that of the 37mm Type 94 (1934) infantry antitank gun having a smaller cartridge case. The Type 95 tank’s one good point was that its 6-cylinder diesel engine provided it with sufficient power and speed. (Howard Gerrard)

During the night, coordinated local counter-attacks were beaten off with little difficulty, thanks in part to naval gunfire and star shells combining with the artillery of the 11th Marines. These were not the expected suicidal banzai attacks, but took a more coherent form; the first time the Americans had experienced this sort of attack.

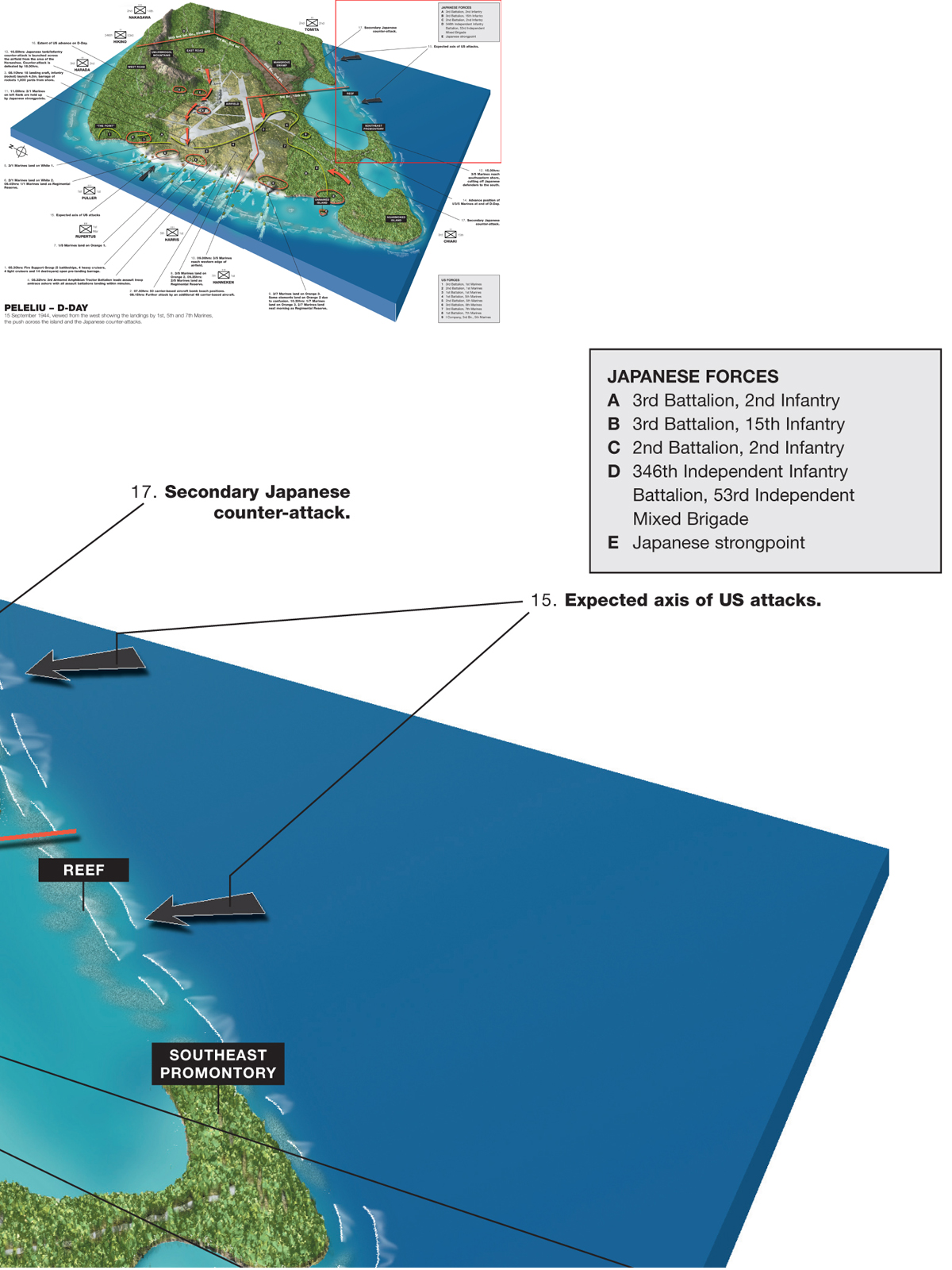

One major Japanese counterattack occurred at around 1650hrs on D-Day, consisting of a tank-infantry sortie in force across the northern portion of the airfield. This attack had been expected by the Marines, especially those of the 5th Marines facing open ground in front of the airfield, and accordingly the regimental commanders had brought up artillery and heavy machine guns as well as tanks to support that area.

Increase in Japanese artillery and mortar fire in that area was the first indication that something was brewing. Soon after Japanese infantry was observed advancing across the airfield, not as a fanatical, drunken banzai charge but as a coolly disciplined advance of veteran infantrymen. A Navy air observer spotted Japanese tanks forming east of the ridges above the airfield with more infantry riding on them. These tanks moved forward, passing through the Japanese infantry advancing across the airfield and some 400 yards in front of the Marine lines. For a moment, but only for a moment, the Japanese counter-attack looked like a serious coordinated movement. Then the formation went to pieces. Inexplicably, the Japanese tank drivers opened their throttles wide and raced towards the Marine lines. Charging like the proverbial “Bats outa Hell,” with the few infantry atop the tanks clinging on for dear life, they left their accompanying infantry foot support far behind.

No positive account exists of what happened thereafter. The tanks involved in the charge numbered between 13 and 17 (insufficient pieces were left afterwards to give a definite count) and headed for the Marine lines, cutting diagonally across the front of 2/1, who subjected them to murderous flanking fire from all weapons, small arms, light and heavy machine guns, 37mm antitank guns and artillery. Two of the Japanese tanks veered off into the lines of 2/1, hurtling over a coral embankment and crashing into a swamp, the escaping crews were quickly disposed of by the Marines.

Meantime, the remaining tanks came under heavy fire from the marines of 1/5, while the advancing Japanese infantry was subjected to fire and bombing from a passing Navy dive bomber.

The tanks and their riding infantry were decimated as they passed right through the Marine lines which simply closed behind them. Exactly who knocked out what is, to this day, a mystery. Only two of the Japanese tanks escaped the massacre, although if all confirmed hits were taken into account the Japanese tank force must have numbered some 180 tanks!

As for the Japanese infantry, when the Marines looked back after the tanks had broken through their lines, the Japanese infantry was nowhere in sight. Whether they had been annihilated by the devastating Marine fire or whether they withdrew after seeing their tank support being decimated remains conjecture but the counterattack was over. It is doubtful we shall ever learn the definitive answer.

Several more smaller counterattacks occurred up and down the line during the afternoon of D-Day, none of which amounted to much except for one at about 1730hrs when infantry, supported by two tanks (probably the two that escaped earlier), attacked the lines of the 1st and 5th Marines. Both tanks were destroyed and the Japanese infantry failed to reach the Marine lines.

The aftermath of one of the many counterattacks by the Japanese during the fighting around the airfield. These were not the frenzied banzai attacks as experienced previously by the Marines, but coordinated small-scale attacks, probing the Marine lines, though the outcome was usually the same.

One thing was noted by the Marines with regard to the Japanese counter-attacks and that was the fact that these were coordinated and disciplined attacks, rather than the frenzied banzai suicide charges experienced before. This was the first indication that something different was in store for the attacking Marines on Peleliu.

General Rupertus and his staff landed on D+1 at 0950hrs and took over direction of operations, taking over the command post that General D.P. Smith had set up in the large antitank ditch just inland of Beach Orange 2 on D-Day. This was a somewhat uncomfortable position for General Rupertus, as the area was still under Japanese fire from time to time and particularly as his leg and broken ankle were still in a plaster cast.

Nevertheless, plans were drawn up, based on the original battle plan for the advance across the island, in spite of the fact that the D-Day objectives had not been achieved and Puller’s 1st Marines on the left flank were in serious trouble.

On the right flank (south) the 7th Marines were to advance east and south. The 1st Battalion was anchored on the western shore at Beach Orange 3 and the 3rd Battalion was inland, but held up by a large Japanese reinforced concrete blockhouse, which they had not been able to reduce before nightfall on D-Day. At 0800hrs the 3/7 resumed their assault on the blockhouse, this time with the assistance of naval gunfire and tanks, but the blockhouse was only finally reduced by direct assault from demolition teams under a smokescreen. Company I reached the eastern shore at approximately 0925hrs and proceeded to dig in against possible counterlandings from the Japanese on Koror or Babelthuap, which were a definite possibility.

In the meantime, the 1/7 attacked southwards over terrain described as “low and flat” (Intelligence described almost all of Peleliu as low and flat). This was covered with scrub overgrowth that hampered progress. Most of the Japanese defenses in this area faced seaward in the anticipation of this area being part of possible landing beaches and, as such, 1/7 were assaulting these defenses from their less protected flanks and rear. Nevertheless, the area was still honeycombed with casemates, blockhouses, bunkers and pillboxes, all mutually supporting with trenches and rifle pits with well-cleared fields of fire for rifles and machine guns.

The going was grim and deadly but once again the Japanese had no intention of giving up lightly. They made the Marines pay dearly for every inch of Peleliu. 1/7 pushed forwards, supported by naval gunfire, air strikes and medium tanks; men from K/3/7 reached the southern shore around 1025hrs.

One other factor hampering the Marines’ progress was the temperature on Peleliu. During the day, it was over 100°F and the strains of protracted fighting and dehydration were beginning to tell. The advance was halted around 1200hrs until water and fresh supplies could be brought up. Unfortunately for the Marines, the drums the water was brought to them in had previously been used to store aviation fuel and had not been properly cleaned. This was to temporarily incapacitate many of the much-needed Marine infantrymen.

A wounded Marine gets a most welcome drink from a buddy. Temperatures were over 100°F during the day and drinking water was always in short supply. Initial supplies of water landed came in drums previously used for storing gasoline and inadequately cleaned. Many marines suffered the effects of drinking the tainted water.

The rest of D+1 was spent bringing up supplies, together with tanks which assisted in reducing the remaining Japanese defenses, while covering engineers clearing the profusion of mines which had been planted on the beach, this being the only approach by land.

D+2 saw the 7th Marines pushing further south, assaulting the southeast and southwest promontories of the southern shore. 3/7 were to assault the southeast promontory but the jump-off was delayed from 0800 to 1000hrs after another minefield was discovered and had to be cleared by the engineers. Then, after an artillery and mortar barrage, Company L advanced supported by three medium tanks. By 1026hrs a foothold was gained and, after some fierce fighting, the area was secured. The entire promontory was taken by 1320hrs.

The southwestern promontory, much larger than the southeastern promontory, was the target of 1/7. They launched their assault at 0835hrs, with the Marines meeting stiff resistance from the start. Progress was halted while tanks and armored LVT(A)s were brought up and artillery pounded the Japanese defenses. The attack resumed at 1430hrs. This time they succeeded in taking the Japanese first line of defense. Although resistance was stubborn and progress was slow, by nightfall of D+2 half of the promontory was in Marine hands.

During the night of D+2/D+3, additional armor (tanks and 75mm gun-mounted halftracks) was brought up and at 1000hrs of D+3 the advance was resumed. Again progress was painfully slow with many reserve elements being attacked by Japanese from bypassed caves and underground emplacements. At 1344hrs elements of Companies A and C reached the southern shores, though the area being assaulted by Company B was still heavily defended. Tank support had withdrawn to re-arm and before Company B was in a position to resume the attack, a bulldozer was needed to extricate the gun-mounted half-tracks, which had become bogged down. At that time, several explosions were heard from the Japanese defenses and it was found that remaining Japanese defenders had finished the job for the Marines. The final handful leaped from the cliff tops into the sea in an effort to escape, only to be picked off by Marine riflemen.

With the taking of the two promontories, the southern part of Peleliu was secured. 1/7 and 3/7 squared themselves away for a well-earned rest, while headquarters reported “1520 hours D+3, 7th Marines mission on Peleliu completed.” Unfortunately, this was not quite the case.

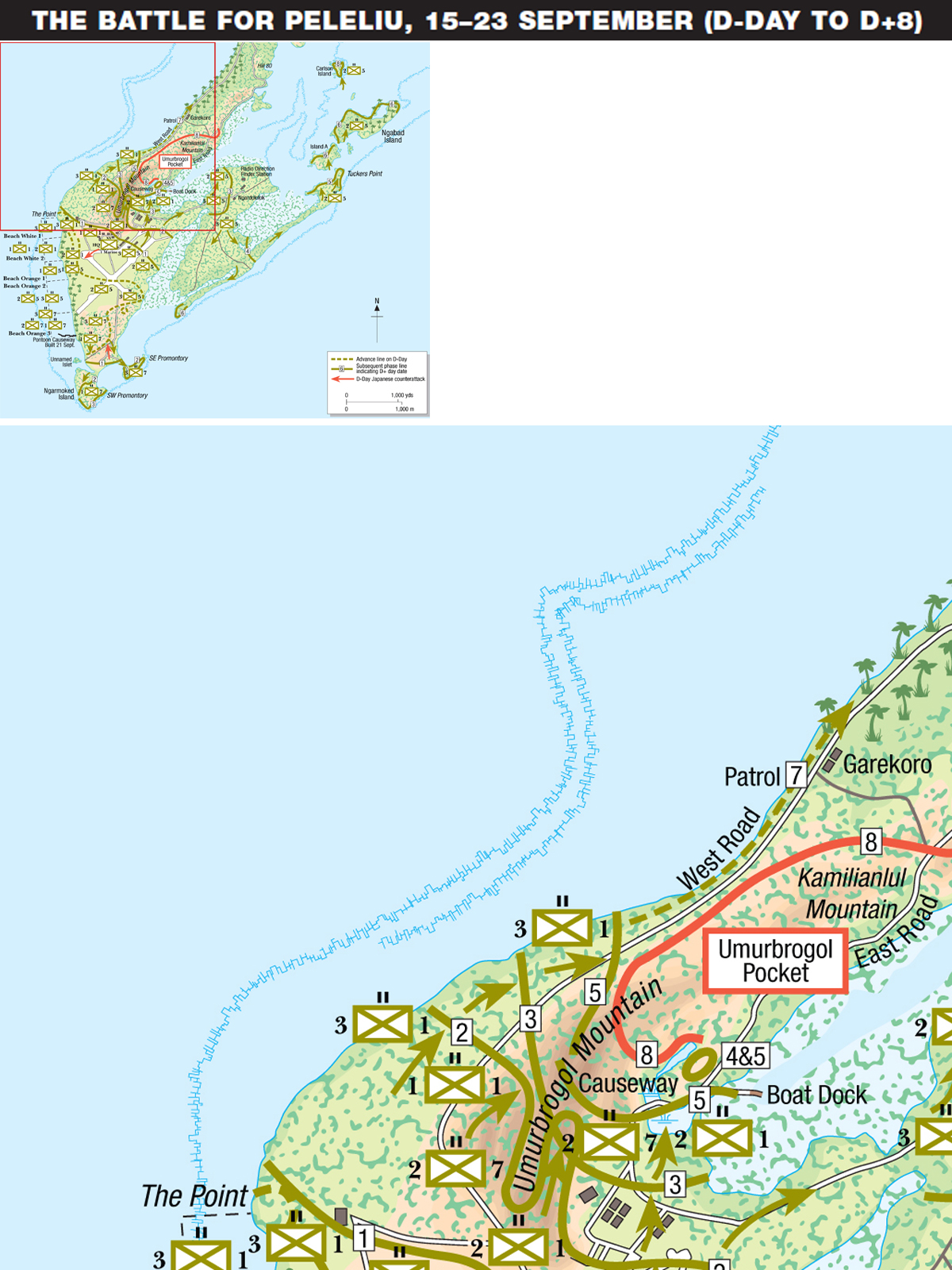

Whilst the 7th Marines were successfully securing the south, the 5th Marines in the center prepared to expand on their gains of D-Day. On D+1 the 5th Marines were to push east across the airfield and then swing northeast, pivoting on the 1st Marines’ left flank. In little over an hour 1/5 swept the entire northern area of the airfield with the only serious resistance coming from a series of emplacements around the hangar area. This area was secured by late afternoon of D+1, but only after heavy fighting and the front line having to be drawn back to a large anti-tank ditch for the night.

Meanwhile, 2/5, advancing on 1/5’s right flank, was making slow progress against open ground and heavy Japanese resistance. Furthermore, on the east of the airfield, woods gave way to a mangrove swamp. Both the woods and swamp were infested with Japanese emplacements which had to be reduced by costly hand-to-hand fighting. But, by nightfall of D+1, 2/5 was alongside and tied in with 1/5, ready for the next day’s advance.

Because of the advances of 2/5 on its left and the 7th Marines on its right, 3/5 was practically pinched out of operations on D+1, reduced to securing its positions along the shoreline and assisting 2/5 and 3/7 where possible. Colonel Walt, who had taken over temporary command of 3/5, was replaced by Maj John H. Gustafson and returned to his post of Regimental Executive Officer, 5th Marines.

As the Marines pushed inland they encountered varying terrain from dense underbrush, as here, to swamps, grasslands and eventually mountains. The terrain on Peleliu made the island a defender’s dream and the Japanese used it to full advantage.

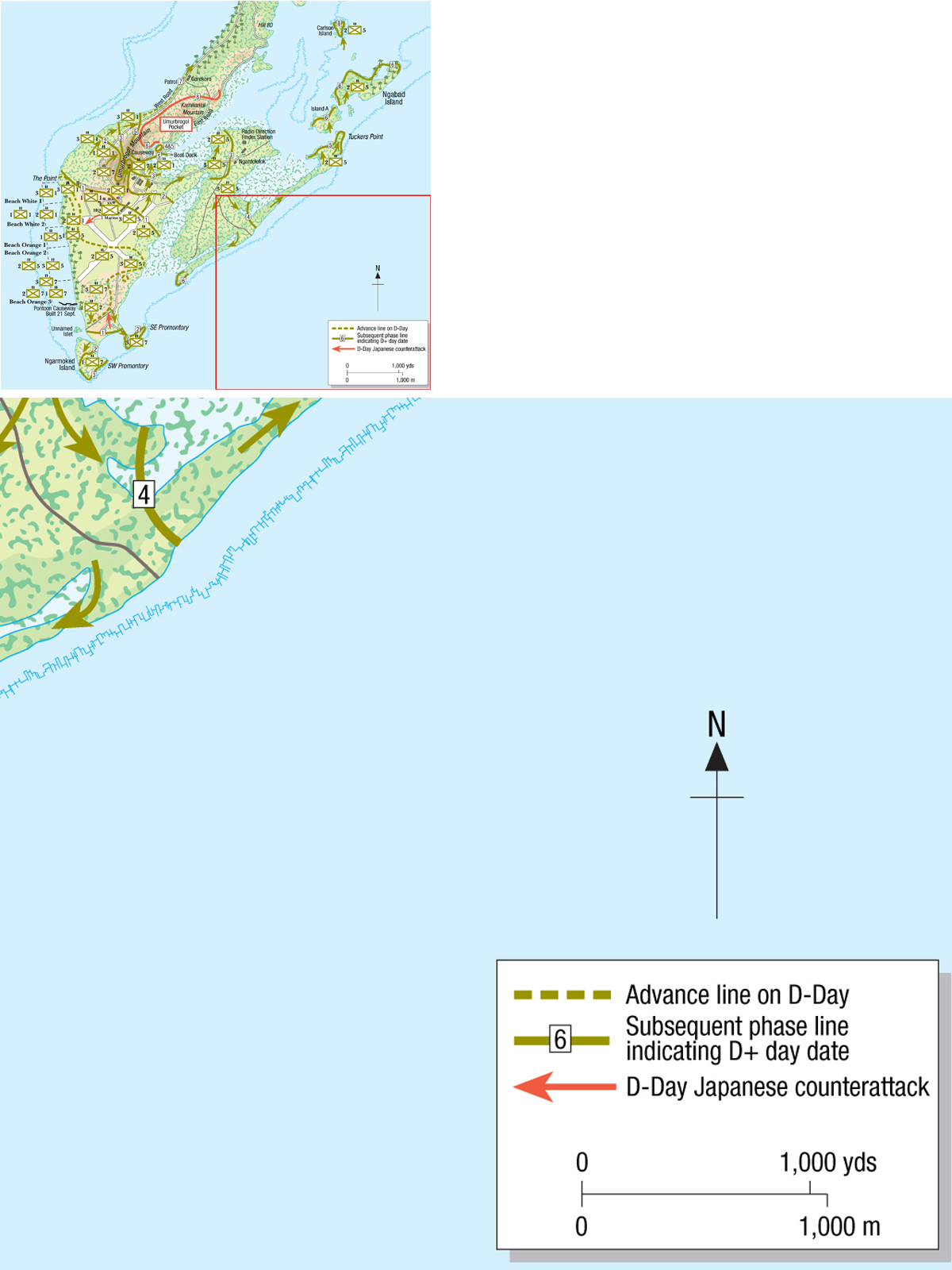

A Marine “war dog” handler reads a message he has just received from his canine dispatch runner. War dogs were used extensively by the Marines throughout the Pacific, they were excellent at carrying messages as here, and also made superb lookouts, soon picking up the scent of any approaching Japanese infiltrators.

D+2 saw the 5th Marines advancing to the northeast, but they began to come under flanking fire from Japanese positions on the high ground to the front of the 1st Marines. 1/5 reached its objectives by mid-morning of D+2 where it held until relieved by 3/5. But when 3/5 tried to resume the advance in the afternoon it became pinned down from heavy flanking fire on its left.

On the right, 2/5 had more success being concealed in the woods from Japanese artillery and mortar fire.

Resistance on the ground was light and 2/5 was able to advance to beyond its objective line, though the heat and terrain began to take their toll on the Marines. Frequent halts had to be called, but by nightfall of D+2, 2/5 was tied in with 3/5 on the left and the shoreline on the right.

D+3 (18 September) saw the 5th Marines making slow but continuous progress. On the left, the regimental boundary was the road that skirted the high ground of the Umurbrogol Mountains, which were giving Puller’s 1st Marines so much trouble. On the right, things were much different. Jumping off at 0700hrs, 2/5 hacked its way through dense jungle scrub, encountering only scattered resistance. Within two hours lead elements reached an improved road heading eastwards to the shores of Peleliu’s northeastern peninsula. This road was so closely bordered by swamps as to become a causeway which could be perilous to an advance. A patrol was therefore sent in advance of the main body and, drawing no fire, an air strike was called in advance of a crossing in force.

Unfortunately the air strike missed completely so an artillery barrage was called for. Following this, elements of Companies G and F began crossing the causeway. Then, from out of the blue, came another unexpected air strike which strafed the advancing Marines, resulting in 34 casualties from “friendly fire.”

Nevertheless the bridgehead was established, but suffered further casualties from misplaced friendly artillery and mortar fire. With this new tactical opening, Regimental HQ shifted 3/5 (leaving Company L tied in with the 1st Marines) eastwards across the causeway to assist 2/5. By nightfall of D+3 they had a bridgehead north and east, facing the main Ngardololok installations shown on Marine maps and in reports as the “RDF area” as it contained a radio direction finder station.

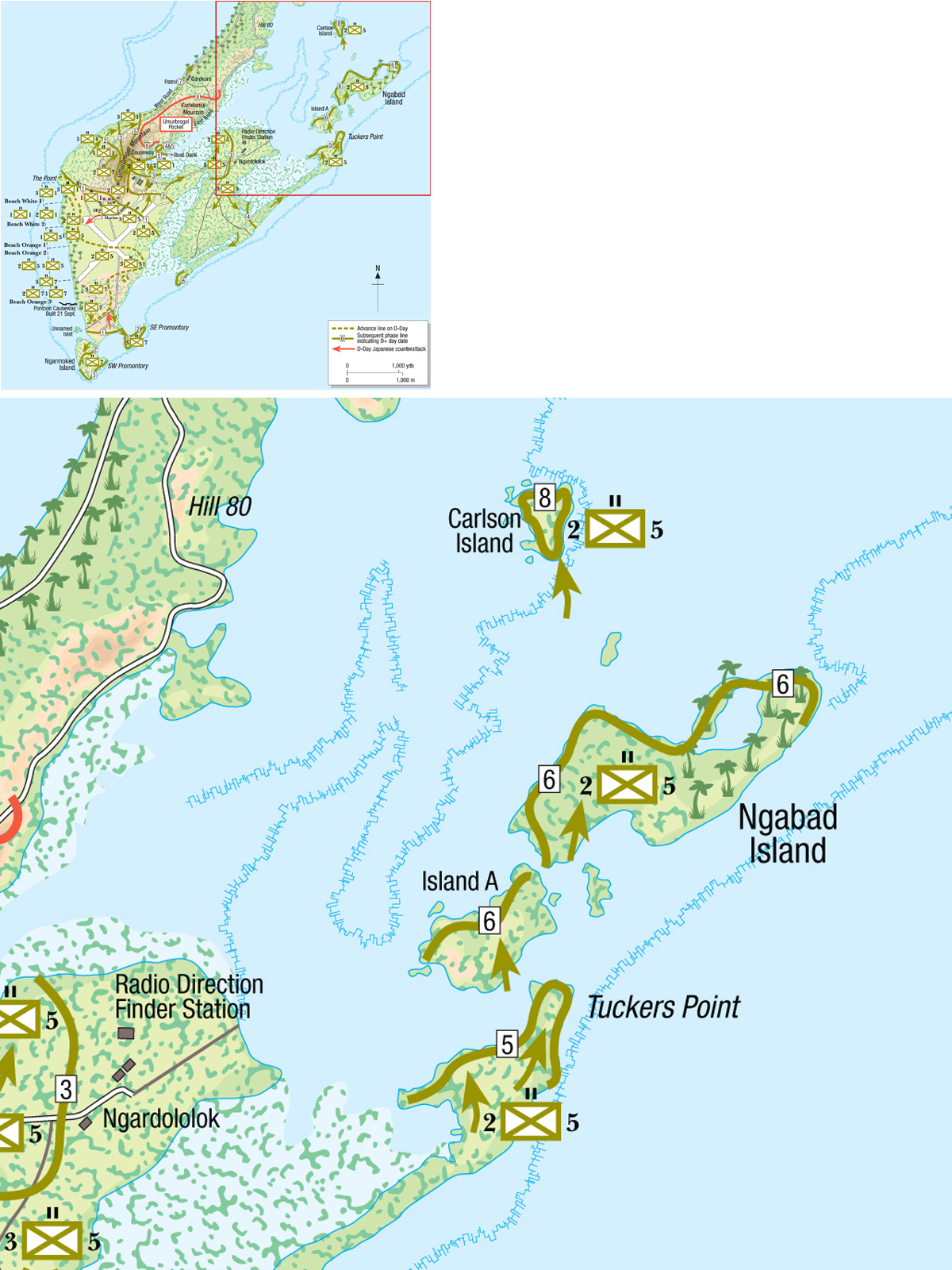

On D+4 2/5 and 3/5 advanced on the RDF area against only light resistance from scattered Japanese stragglers, most of whom chose to hide rather than fight. Both battalions pushed on and by the end of D+4 3/5 had reached the eastern shoreline and later the southern shores (designated Beach Purple). By D+6 they had secured the whole peninsula, while 2/5 continued east and north stopping short of Island A (an islet just off the causeway) which proved to be deserted. This discovery was made by a patrol sent across the previous day (D+5). 2/5 then pushed further north to the second, larger island of Ngabad, again without opposition.

But on the Division’s left flank things were going far from well. Puller’s 1st Marines had, from the outset on D-Day, run up against fierce, well-coordinated resistance from what would prove to be the main Japanese defenses in depth, centered around the Umurbrogol Mountains.

On D+1 MajGen Rupertus, upon arriving at the beachhead command post, ordered 2/7 (the division reserve) transferred to Puller’s hard-pressed 1st Marines in an effort to “maintain momentum,” as Rupertus would say to Puller many times.

2/1 was facing east and on D+1 swung left (north) to take the built-up area between the airfield and the mountains. This they achieved, crossing the airfield within half an hour. On the left, however, 3/1 was unable to advance at all and the regimental reserve, 1/1, was committed in the afternoon to assist. After bitter fighting, Marine infantry supported by tanks captured a 500-yard segment of the ridge and Company B was able to make contact with Company K which had been isolated for some 30 hours. A concerted counterattack by the Japanese on the night of D+1 was beaten off, but the hard fighting had taken a toll. By the morning of D+2, Company K was down to 78 men remaining from the original 235 and was ordered to the rear into reserve.

On the 1st Marines’ front the fighting was murderous from the beginning. Here Marines gently pass a wounded comrade down to receive treatment from the ever-present navy corpsmen. Note the rifle grenade in the foreground, a very useful weapon against bunkers and caves.

Peleliu was practically all coral rock, making digging-in a practical impossibility. The best anyone could manage was to pile up boulders and cover them with coral dust as these two Marines have done here.

On D+2 elements of the 1st Marines came into contact for the first time with the Umurbrogol Mountains. Aerial photographs did little justice to the real nature of the mountains described later in the 1st Marines regimental narrative thus:

“a contorted mass of coral, strewn with rubble crags, ridges and gulches”.

By D+2 the 1st Marines had already suffered over 1,000 casualties and as a result all three battalions were assembled in line on the regimental front, 3/1 on the left flank, 1/1 in the center and 2/1 on the right flank, with the newly arrived 2/7 in reserve.

2/1 were the first to encounter the Umurbrogol defenses, being stopped dead in their tracks after initial good progress by the first of many ridges (this one christened Hill 200). The men of 2/1 scaled the slopes and, after bitter hand-to-hand fighting and many casualties, by nightfall of D+2 had secured the crest of Hill 200 but immediately came under fire from the next ridge (Hill 210), thus the pattern was set.

In the center, 1/1 progressed well, until confronting a substantial reinforced concrete blockhouse, unmarked by naval gunfire, and which had previously been reported “destroyed” by Admiral Oldendorf in his pre-invasion bombardments. This complex was only taken after fire control parties called in fire from naval 14in. guns directly onto the emplacements.

On the left the picture was a little brighter as 3/1 was able to advance along the comparatively flat coastal plain but had to call a halt when it was in danger of losing contact with 1/1 on its right flank.

By D+3 Puller’s 1st Marines had suffered 1,236 casualties yet Puller was still being urged on by MajGen Rupertus to “maintain the momentum” and, as a result, all available reserves including pioneers, engineers, and headquarters personnel were committed as infantrymen. Also 2/7, the division reserve, moved in to replace 1/1 in the center, which went into reserve. D+3 was a repeat of D+2 and would be repeated day after day. 2/1 took Hill 210, whilst the Japanese counter-attacked Hill 200, forcing the Marines to withdraw. In the afternoon, 2/1’s situation was so desperate that Company B, 1/1, having just gone into reserve, was sent to assist 2/1 assaulting yet another ridge (Hill 205). This hill turned out to be isolated so Company B pushed on but was thrown back by a complex of defenses that was to become known as “Five Sisters.” On the left once again 3/1 fared best, advancing along the coastal plains, halting again to maintain contact with 2/7 in the center.

After a harrowing night of counterattacks what was left of the 1st Marines plus 2/7 re-assumed the attack on D+4 after a naval and artillery barrage. Once again progress was best on the left, 3/1 pushing forward but again having to halt. In the center, 2/7 slogged from ridge to ridge suffering heavy casualties and 2/1 on the right pushed on over similar terrain against stiff resistance, which got worse with each successive ridge.

“Lady Luck takes a nose-dive” – this LVT(A)4 found a novel way of dealing with this Japanese navy gun, although getting bogged down in soft sand in so doing. However, the Japanese gun and crew have clearly come off worse in the encounter.

Men of the 7th Marines, loaded down with weaponry and personal equipment, move up to relieve Chesty Puller’s 1st Marines. Puller’s almost superhuman efforts to comply with Gen Rupertus’s orders to “maintain momentum” resulted in the 1st Marines suffering staggering casualties on Peleliu, amounting to over 70 per cent killed or wounded.

Although 2/1 did not know it, they were attacking what was to become the final Japanese pocket in the Umurbrogol Mountains.

By the end of D+4 the 1st Marines existed in name only, having suffered almost 1,749 casualties – six fewer casualties than the entire 1st Mar. Div. lost on Guadalcanal. On D+6, after another day of bitter hand-to-hand fighting, Puller was visited by IIIAC commanding general, Roy Geiger. Upon his return to Division Headquarters, after seeing first hand the condition of Puller (a leg wound sustained on Guadalcanal was giving him severe pain) and his men, Geiger conferred with Rupertus and some of his staff and after a bitter argument ordered Rupertus to replace the 1st Marines with the 321st RCT of the 81st Inf. Div., now on Angaur, and send Puller and his crippled unit back to Pavuvu. The 1st Marines by this time reported 1,749 casualties. One Marine later described the fighting in the Umurbrogol, which attests to the level to which the 1st Marines had deteriorated:

“I picked up the rifle of a dead Marine and I went up the hill; I remember no more than a few yards of scarred hillside, I didn’t worry about death anymore, I had resigned from the human race. I crawled and scrambled forward and lay still without any feeling towards any human thing. In the next foxhole was a rifleman. He peered at me through red and painful eyes. I didn’t care about him and he didn’t care about me. As a fighting unit, the 1st Marines was finished. We were no longer human beings, I fired at anything that moved in front of me, friend or foe. I had no friends, I just wanted to kill.”

The IIIAC Reserve for Operation Stalemate II was the 81st Inf. Div., to be used as necessary and then to assault Angaur with two of its three RCTs but only when the situation was “well in hand” on Peleliu. The 81st Inf. Div. Command Post afloat was aboard the USS Fremont (APA-42).

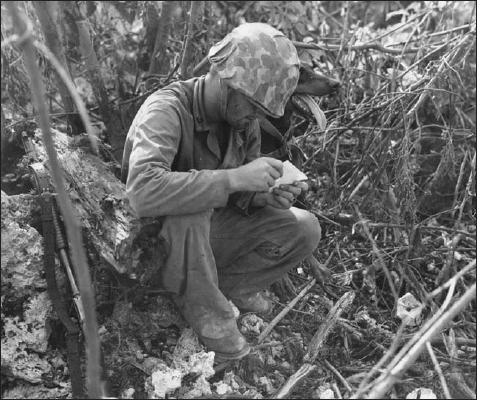

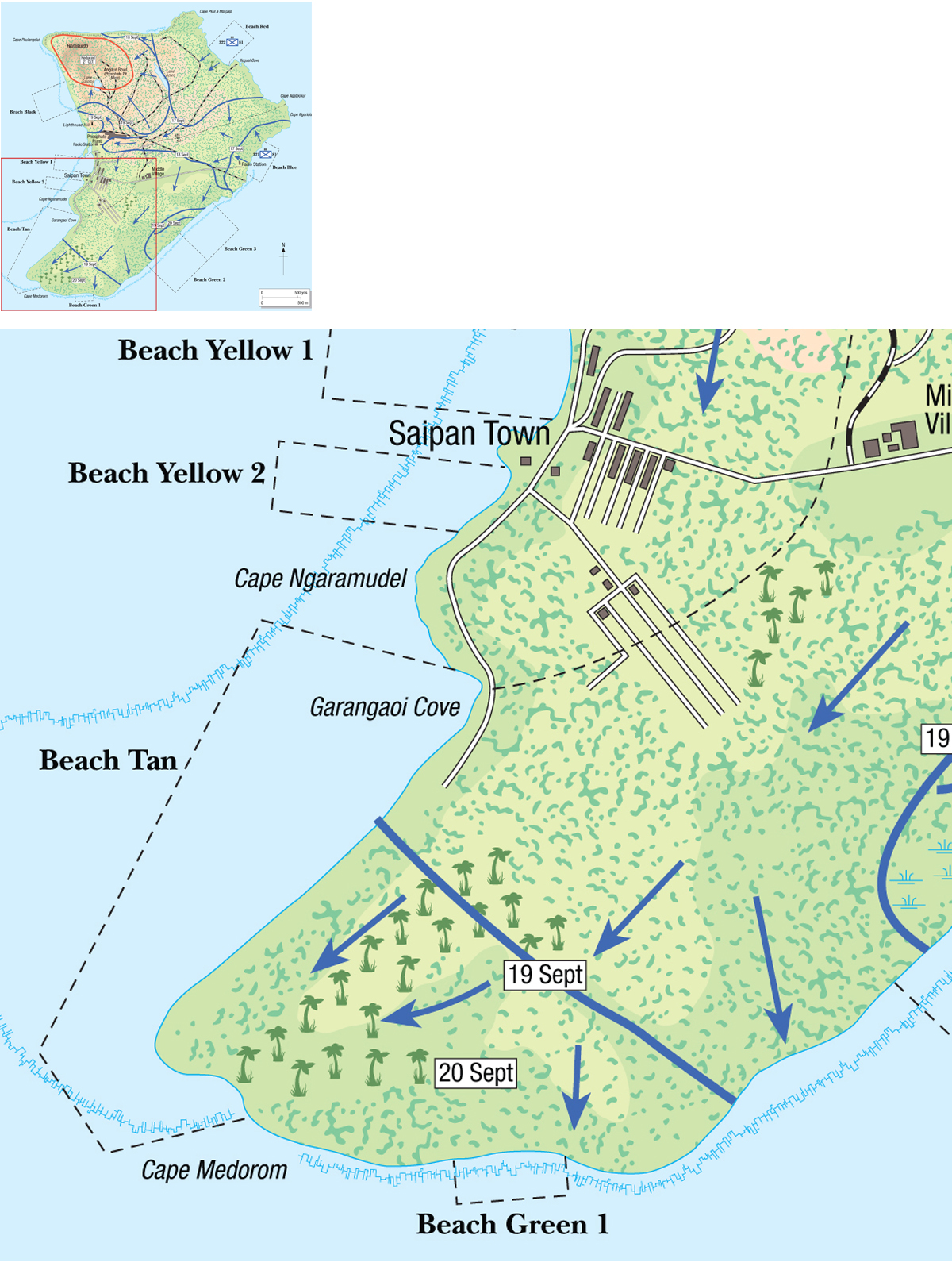

On 16 September (D+1) 1st Mar. Div. commander, General Rupertus, gave the assurance that “Peleliu would be secured in a few more days” and so, on Rupertus’ report, LtGen Geiger issued orders for the assault on Angaur to proceed. F-Day, the Angaur assault was set for 17 September (D+2 on Peleliu). F-Day was used to designate the Angaur assault to prevent confusion with Peleliu’s D-Day. Likewise, G-Hour was used rather than H-Hour. Angaur Island lies 7 miles southwest of Peleliu. Major Goto Ushio of the 1st Battalion, 59th Infantry (Reinforced) detached from the 14th Division, would make his last stand with some 1,400 troops. He had divided the island into four defense sectors and a small central reserve. Major Goto had expected the Americans to land on the superb beaches on the southeast of the island, codenamed Beaches Green 1 and 2 by the Americans; and so it was here Goto constructed his most formidable coastal defenses of steel-reinforced concrete bunkers and blockhouses in addition to numerous antiboat gun emplacements, machine gun nests, and rifle pits. Goto also sowed numerous minefields along the 1,400-yard stretch of beach.

The remnants of Col Chesty Puller’s 1st Marines on their way out of the line having been relieved by elements of the 7th Marines. They were initially told this was only a brief respite for a few days, but it was clear the 1st Marines were a spent force and MajGen Geiger ordered them to return to their base on Pavuvu.

All this would be to no avail as reconnaissance missions over Angaur had spotted all this construction activity months earlier and so the American planners had rejected plans to use the Green Beaches as being too heavily fortified for an amphibious assault, choosing instead the less well-defended Beaches Red and Blue to the north and east.

As planned the 322nd RCT landed on Beach Red on the northeast coast and 321st RCT landed on Beach Blue on the upper southeast, both after a full pre-landing bombardment from the Navy, involving the battleship USS Tennessee (BB-43), one heavy cruiser and three light cruisers. In addition, 40 Dauntless dive-bombers from the aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV-18) bombed and strafed the beaches and the areas immediately inland. As at Peleliu, rocket-firing LCI(G)s saturated the beach areas with 4.5in. rocket salvos in advance of the first assault waves boated in amtracs and preceded by armored LVT(A)s as initial tank support. Both RCTs encountered only small-scale resistance from small arms and mortars on the beaches and were soon pushing inland, although 321st RCT on Beach Blue initially met with some stiff resistance, coming under fire on both flanks from Japanese fortifications on Rockey Point on the left flank and from Cape Ngatpokul on the right. The 323rd RCT remained afloat and conducted a feint off Beach Green.

Soon after the push inland started, the “Wildcats” found themselves snarled up in dense scrub forests infested with Japanese machine guns and snipers. The advance was slow and costly but by nightfall both RCTs had reached their objective lines but were still separated by some 1,500 yards, so the RCTs both formed their own independent perimeter.

During the night, several Japanese counterattacks hit both RCTs causing the Americans to withdraw from some positions. 1/321 fell back some 75 yards in order to regroup and reorganize its lines, but all the Japanese attacks were eventually beaten off.

The second day, after a three-hour artillery bombardment with bombing and strafing sorties from Navy carrier planes, both RCTs advanced with tank support north and west and the right flank of the 321st RCT made contact with 322nd RCT, linking the two advances together. The 322nd RCT pushed west from Beach Red, making good time until they reached the center of the island and the high ground where Maj Goto had sited his final redoubt. By early afternoon, the 322nd had reached the phosphate plant just northeast of Saipan Town (the island’s capital). During 322nd’s advance, the 3rd Battalion came under “friendly fire” from carrier planes due to a mix-up over grid coordinates, resulting in 7 dead and 46 wounded – this did nothing for inter-service cooperation!

The 321st RCT advanced west from Beach Blue with 322nd RCT now on its right flank. The 321st pushed to the south, progressing well until they came up against the formidable defenses of Beach Green, a series of mutually supporting fortifications covering some 1,500 yards, here 1/321 stopped and dug in for the night.

Tank dozer, a bulldozer blade fitted to the front of a Sherman tank, was a very useful and effective weapon at the disposal of the attacking soldiers and Marines on Peleliu. Here one fires on one of the many Japanese defenses after clearing itself a path to a position where it can get a better shot at the defending Japanese.

The 2.36in. M1A1 rocket launcher, or bazooka as it was better known, was a very useful weapon for tackling bunkers and cave defenses and was used extensively by both the Marine and Army units.

On the third day (19 September), after a night of many Japanese infiltrations and small scale counter-attacks, 321st RCT pushed on and succeeded in cutting the island in two. The 321st RCT assaulted the Beach Green defenses from inland and with the aid of tanks and support weapons they were able to reduce the fortifications one by one. This was due mainly to the fact that most of the fortifications’ firing ports faced out to sea, in the direction of the anticipated invasion. In fact the 321st’s attack came from their blind side to the rear, where the fortifications were not mutually supporting. The 321st then wheeled left and pushed down the southwest of the island, stopping just short of the shoreline by nightfall. By the end of the third day, there remained only two areas still in Japanese hands; the biggest and most formidable being in the northeast centered around Romauldo Hill, a series of coral ridges and outcrops even more rugged than, but not as large as, on Peleliu. With the situation reportedly well in hand on Peleliu and Angaur, the IIIAC Reserve, the 81st Inf. Div.’s third RCT, the 323rd, was sent on to its secondary target of Ulithi Island as planned.

On the fourth day the last remaining Japanese pockets of resistance in the south and around the Beach Green defenses were dispatched and 322nd RCT began reducing the Romauldo Pocket. It would take another four weeks of bitter hand-to-hand fighting before Maj Goto and his men, well armed with rifles, machine guns, and mortars, and dug well into the mass of caves and tunnels in the Romauldo Hills, were crushed, and then only with the extensive use of flamethrowers, grenades, and demolitions alongside the sheer determination of the “Wildcats.” On 19 October, Maj Goto was killed during fighting for one of the many cave complexes and three days later the last of the Japanese defenses was reduced, finally bringing to an end organized resistance on Angaur – although Japanese stragglers would be encountered for many months to follow. On the same day, the 81st commander, MajGen Meuller, was contacted by IIIAC commander General Geiger, regarding the need for an RCT for immediate deployment to Peleliu. General Mueller replied that the 321st RCT would be available as soon as it could be reorganized and as such began transferring to Peleliu on 20 September. Angaur was declared secure at 1034hrs on 20 September by MajGen Mueller even though the 322nd RCT overran the last pocket in the hills on 21 October – a full month later.

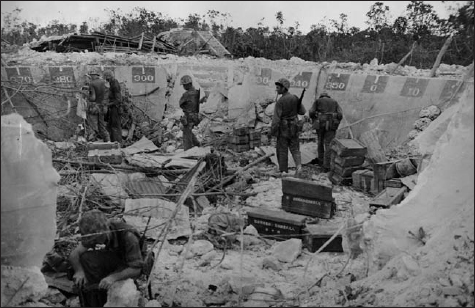

Marines survey one of the Japanese heavy gun positions still littered with the debris of the battle. Note the ample amounts of ammunition the Japanese defenders had and the 360° points of the compass painted on the revetment wall, this weapon being capable of all-round fire, although there is no sign of the gun itself.

Casualties for the 81st were comparatively light compared to those on Peleliu; 260 killed, 1,354 wounded, and 940 incapacitated for non-combat reasons. The Japanese lost an estimated 1,338 killed and 59 taken prisoner.

Japanese hand-drawn artillery caught in the open on the east/west road have suffered the full wrath of Navy and Marine fighter-bombers. With total air superiority, the American air support made short work of any Japanese caught in the open.

Reinforcements were sent to Col Nakagawa on Peleliu from Koror at least twice. On both occasions the Americans intercepted the convoy of landing barges, although some 600 men did make it through to reinforce Nakagawa. Here a Marine MP party checks one of the Japanese barges for survivors.

A further sideshow was conducted 370 miles to the northeast. The 323rd RCT was dispatched on 19 September to secure Ulithi Atoll, a mission originally envisioned for the 321st RCT. On 17 September, F-Day on Angaur, it was decided to commit the Ulithi Landing Force. This necessitated re-embarking some units that had already landed on Angaur including the 906th Field Artillery Battalion. Landing on J-Day, 22 September, they found the atoll’s airfield and seaplane base to be abandoned. Elements of 323rd RCT also searched Ngulu Atoll (16–17 October), Pulo Anna Island (20 November), Kayangel Atoll (28 November–1 December), and Faris Island (1–4 January 1945). Here 17 Japanese were discovered with eight killed, two taken prisoner, and three fleeing by boat. US losses were two killed and five wounded. A major advanced fleet anchorage was established at Ulithi along with a Marine airbase and a Navy seaplane base.

Supplies of fuel and water are floated across the lagoon from supply ships anchored just beyond the reef. Later Seabees blew holes through the reef to allow landing craft to run in to the beach. A pontoon wharf was also constructed by engineers that ran out from Beach Orange to beyond the reef.

On 23 September (D+8), Company G, 2nd Battalion secured the small unnamed and undefended island (later nicknamed “Carlson Island”) north of Ngabad Island, completing the 5th Marines’ original mission. A pontoon causeway was completed by Seabees on Beach Orange 3 on D+6 and this greatly expedited the unloading of supplies and equipment from Landing Ships, Tank (LST) as it bridged the reef impassable to the large beaching craft.

The Japanese attempted to reinforce the garrison on Peleliu on the night of 23/24 September (D+8/9). Barges had been sent on two occasions from Koror and Babelthuap and both times had been intercepted by the Americans, but Col Nakagawa did receive almost a battalion’s (2nd Battalion, 15th Infantry) worth of fresh, if slightly mauled, troops. The need to secure northern Peleliu became more pressing than the elimination of defenses in the Umurbrogol Mountains to prevent further reinforcement landings.

The 81st Inf. Div.’s 321st RCT began arriving on 23 September from Angaur and began to relieve Puller’s battered 1st Marines who were initially withdrawn to the south of the island to rest. The 321st RCT landed over the Orange Beaches task organized as follows:

321st Infantry

Company A, 306th Engineer Combat Battalion

Detachment, HQ and Service Company, 306th Engineer Combat Battalion

Company A (Collecting), 306th Medical Battalion

Company D (Clearing) (– two platoons), 306th Medical Battalion

Detachment, HQ Company, 306th Medical Battalion

154th Engineer Combat Battalion (– one company)

Detachment, HQ and Service Company, 1138th Engineer Combat Group

Detachment, 592d Joint Assault Signal Company

Detachment, 481st Transportation Corps Amphibious Truck Company (DUKW)

Company B, 726th Amphibian Tractor Battalion

Detachment, HQ and Service Company, 726th Amphibian Tractor Battalion

Company A, 710th Tank Battalion

Provisional 81mm Mortar Platoon, 710th Tank Battalion

Company D, 88th Chemical Battalion (Motorized) (4.2in. mortar)

Detachment, Provisional Graves Registration Company, 81st Inf. Div.

Detachment, 81st Signal Company

Detachment, 81st Quartermaster Company

Detachment, 81st Ordnance Light Maintenance Company

Detachment, Translator-Interpreter Team A, HQ Company, Central Pacific Area

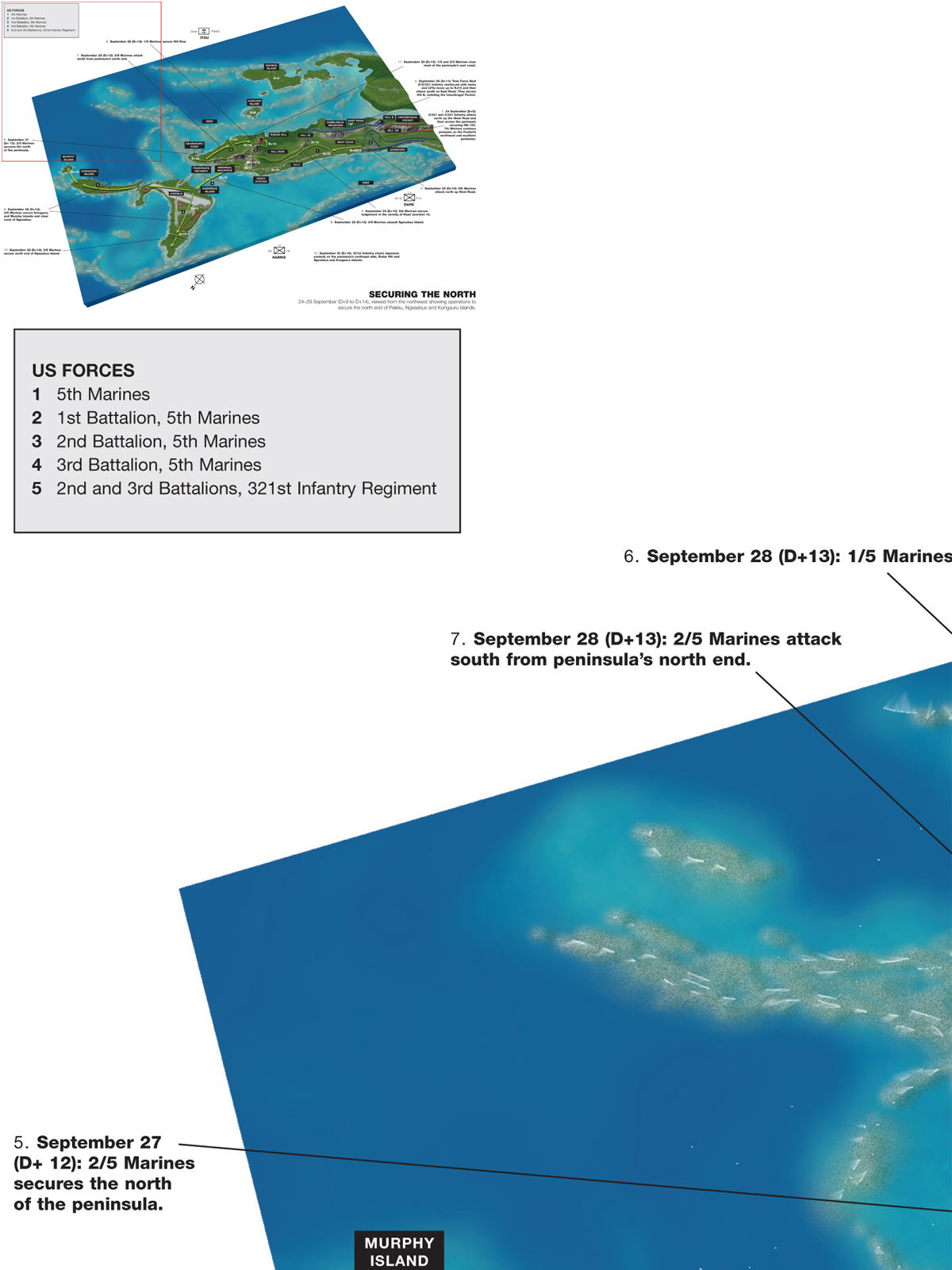

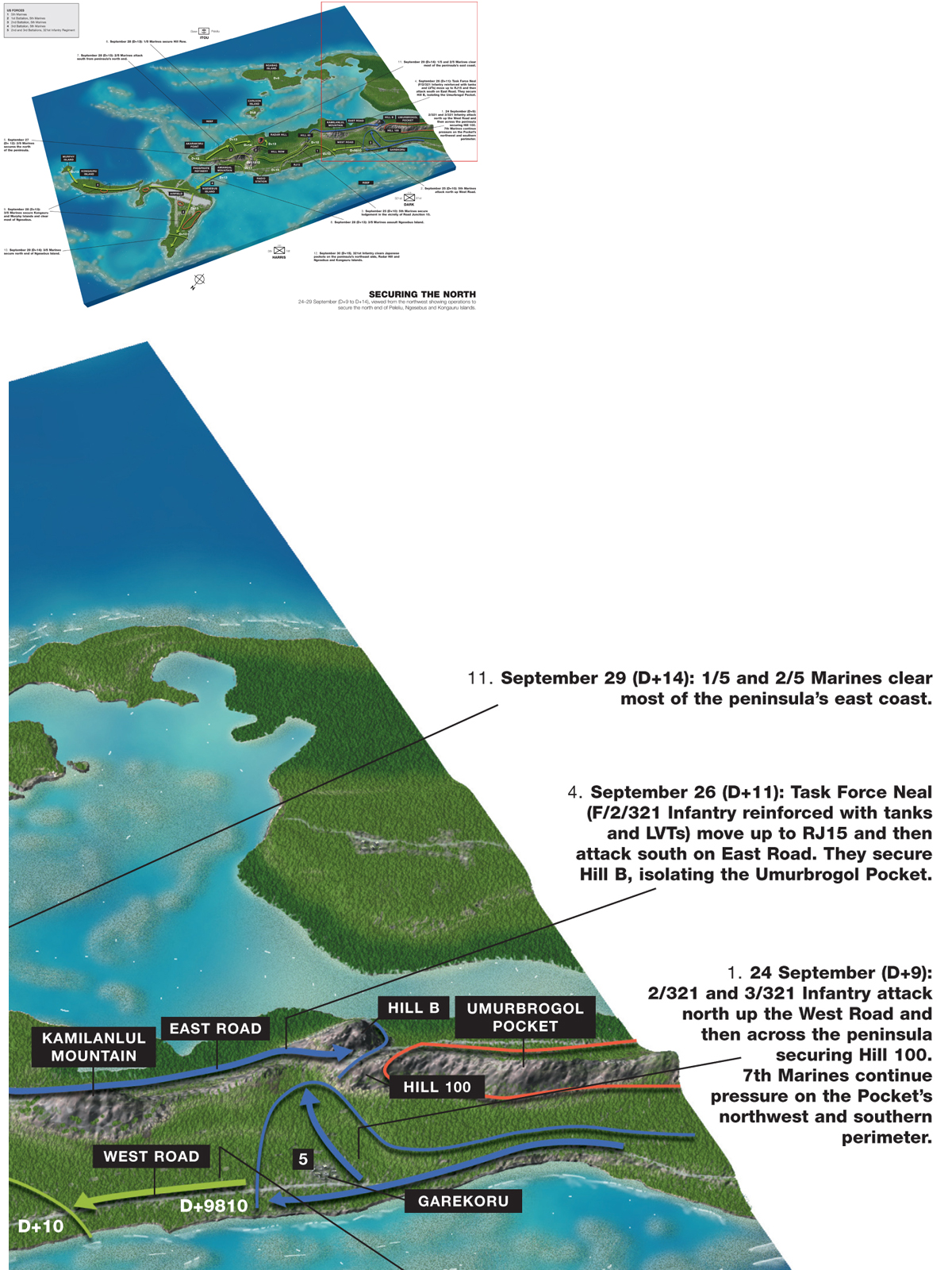

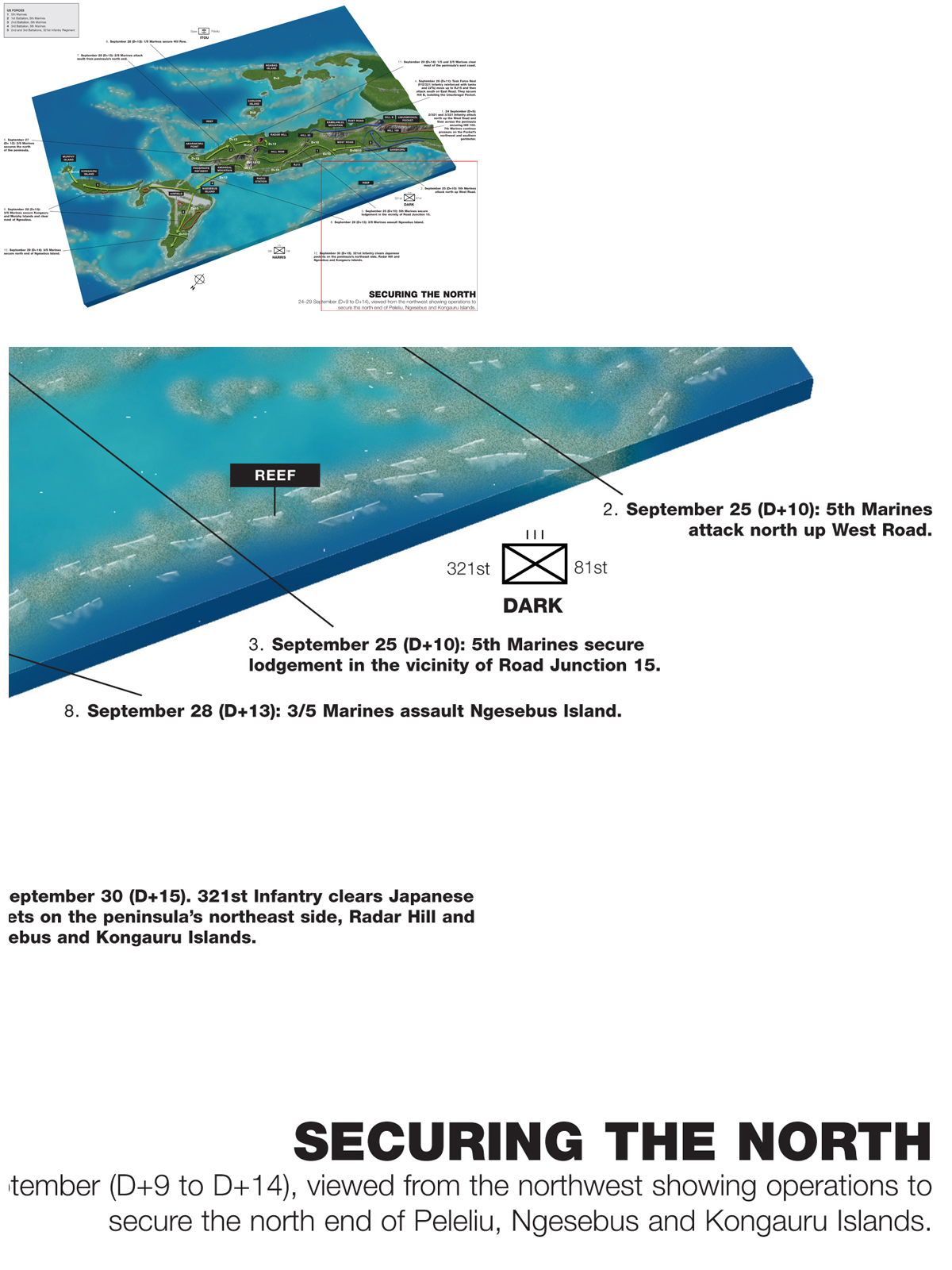

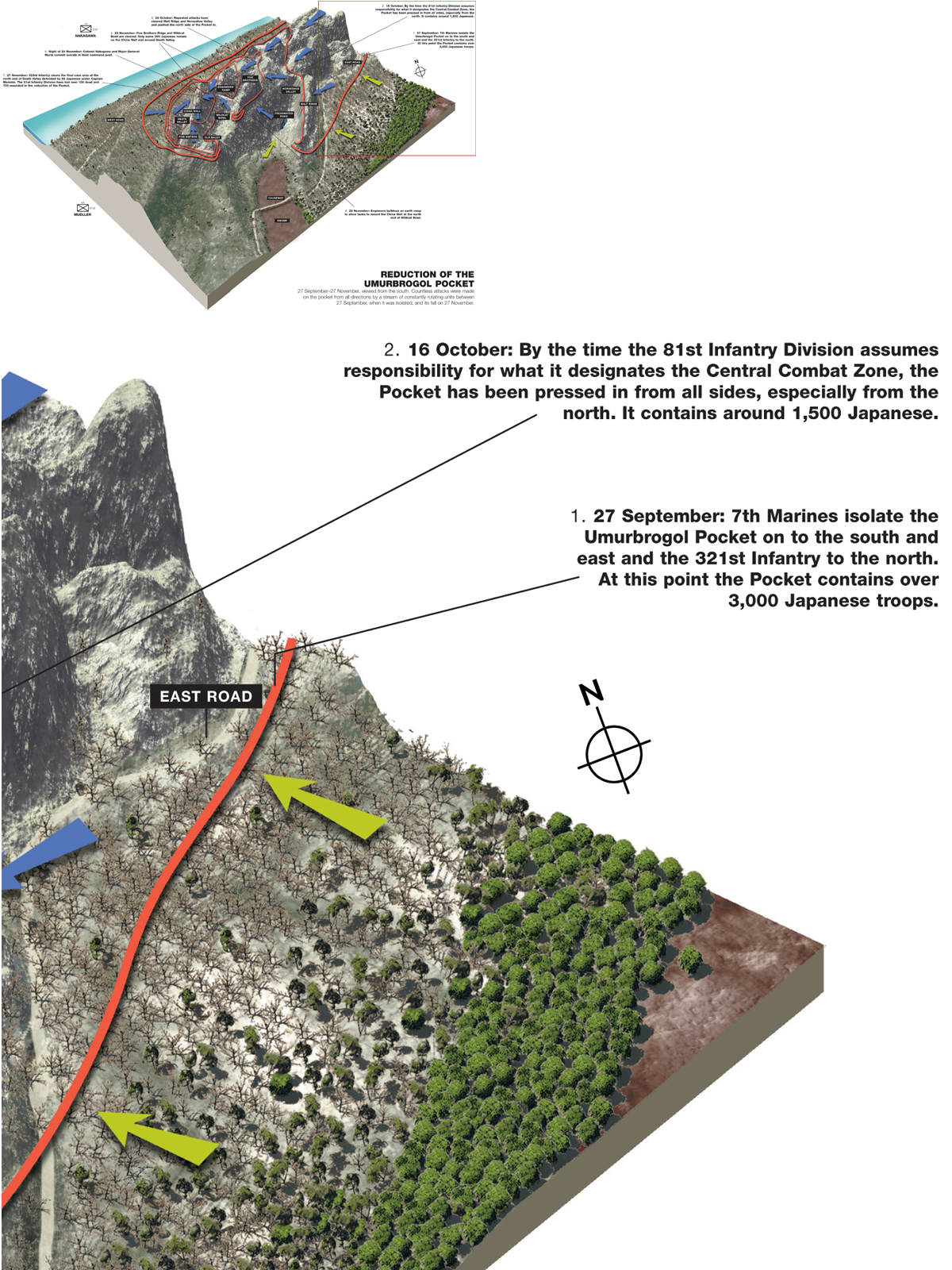

On 24 September (D+9) the 321st RCT began to drive north up the peninsula. The plan was for 321st RCT to push past the Umurbrogol Pocket with the 5th Marines, passing through 321st RCT and on into northern Peleliu, with the 7th Marines taking over the 1st Marines’ positions. The West Road running up the peninsula would be 321st’s main route for the drive north, but the Japanese still held the coral knobs and ridges that dominated the road, and brought anything on the road under murderous fire.

The terrain to the east side of the road made it impossible to use tanks or any other vehicle, thus forcing the use of infantry with no close support, climbing and clambering over coral and ridges to protect the right flank. Once these ridges were taken, vehicles could use the West Road to support and supply the advance.

The textbook assault on Ngesebus island is watched by senior officers of Marines, Army and Navy at the invitation of Gen Rupertus. The operation was perfectly executed; here LVT(A)4s cross the narrow stretch of water between Peleliu and Ngesebus on 28 September. As on D-Day the armored LVTs were to precede the troop-carrying amtracs to provide armored support on the beachhead.

The 321st had relieved the 3/1 Marines that had been tied to 3/7 on the right flank, orders required 3/7 to advance behind 2/321 along the high ground as the soldiers pushed northeast. However, 3/7 were soon outpaced by 2/321 on the flat ground but instead of attacking the ridges 2/321 units abandoned them for the road, reporting 3/7 were not keeping up with them. Colonel Hanneken ordered 3/7 to capture the ridges abandoned by 2/321, which they did at some cost – another setback in Army–Marine relations! The 321st pushed on and by D+10 the 5th Marines were able to pass through them for the final drive at the ruins of Garekoru Village. On the afternoon of D+10 1/5 seized the destroyed radio station complex to the north of Garekoru with 3/5 taking high ground on 1/5’s right. Japanese defenses were as formidable as any on Peleliu, but were reduced by tanks, flamethrowers, and demolition charges, many of the defending unit being poorly trained Navy construction personnel.

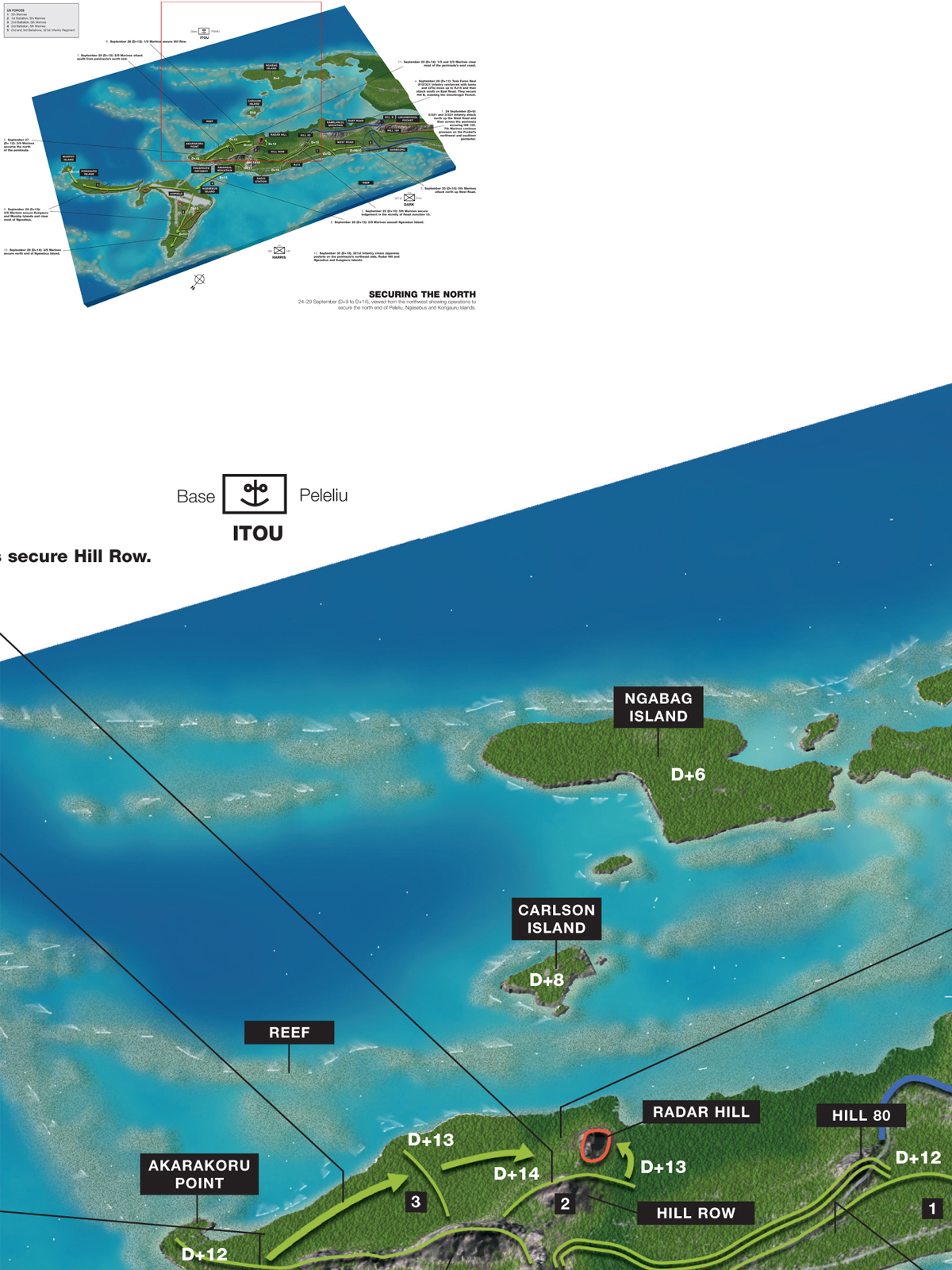

Four steep-sided limestone hills running east–west across the northeastern peninsula were attacked on D+11. These had been dubbed Hills 1, 2, and 3 and Radar Hill, known as “Hill Row,” and were actually the southern arm of Amiangal Ridge. They were defended by some 1,500 infantrymen, artillerymen, and naval construction troops plus reinforcements from Koror. As the right progressed 2/5 side-stepped to the west and pushed on to the north, leaving 1/5 to continue the assault and by nightfall had taken the southern end of the final ridge. What 2/5 did not know was that they were facing the most comprehensive cave system on Peleliu which was the underground home of the Japanese naval construction units who were, luckily for the Marines, better miners than infantrymen.

Fighting continued all day D+11 and D+12 with several small scale counterattacks during the night but by the end of D+12 2/5 had secured the northern shore (Akarakoro Point) though if the Marines held the area above ground, the Japanese still held it underground! It would take weeks for the Marines to finally quash all resistance on Akarakoro Point, then only by blasting closed all the tunnel entrances, sealing the Japanese defenders inside to their fate. The Marines were amazed several weeks later to witness the Japanese Navy survivors digging their way out to the surface.

2/5 then turned around and attacked south in support of 1/5, still slogging away at the four rocky hills of Hill Row. After two days of bitter fighting the Marines blasted and burned their way to the tops of Hill Row, most of the Japanese defenders being sealed in their caves and left to their own devices, but by D+14 all but the Umurbrogol Pocket had been taken.

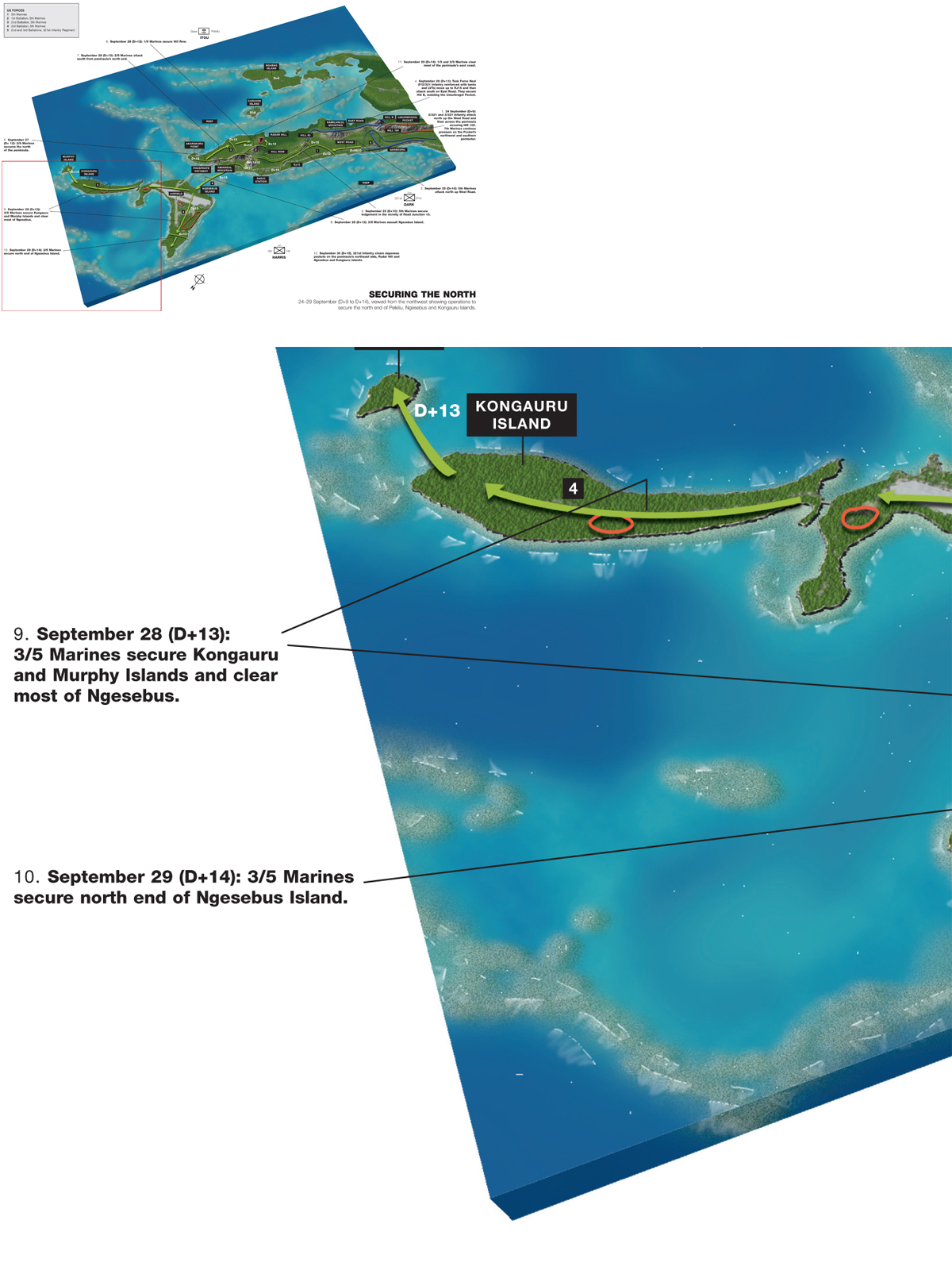

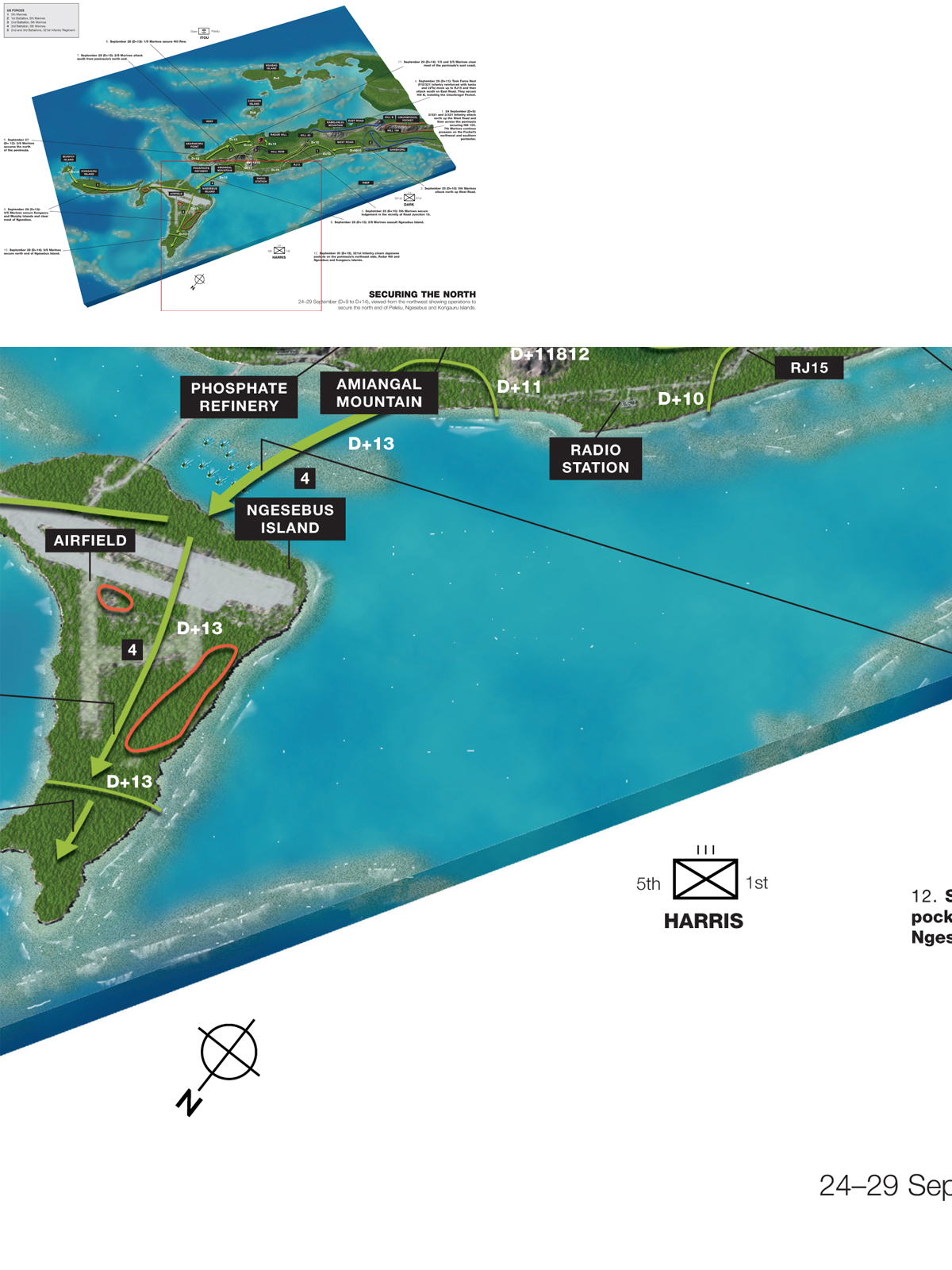

Whilst their comrades of 1/5 and 2/5 battled it out on Hill Row, Marines of 3/5 prepared for an amphibious assault on Ngesebus and Kongauru Islands, some 300 yards off Akarakora Point. Ngesebus Island was L-shaped and around 2,500 yards long. Much smaller Kongauru Island lay off its northeastern tip. Ngesebus was surrounded by a coral reef estimated to be 4ft deep and had been connected to mainland Peleliu by a wooden causeway, this having been partially destroyed during the preliminary bombardment. Ngesebus Island had been sited as one of the prime targets on Peleliu during the planning stages due to the presence of a secondary airfield, albeit a smaller fighter strip. Now, with the campaign in full swing and Japanese airpower on Peleliu destroyed, a much greater priority for the Americans was to prevent the use of Ngesebus and Kongauru Islands as a staging area for Japanese reinforcements sent by General Inoue from Koror and Babelthuap.

The landing planned by Col Harris and LtCol Walt was a textbook operation. Major Gustafason, 3/5, was to land on the shores of Ngesebus after a massive pre-landing naval bombardment from the battleship USS Mississippi (BB-41), the cruisers Denver (CL-58) and Columbus (CA-74), and land-based artillery. Marine Corsair fighter-bombers from VMF-114 operating from Peleliu Airfield would provide air cover. Notably, this was the first time a US Marine amphibious landing had been supported entirely by Marine aviation. Major General Rupertus was so supremely confident in the success of the wholly Marine operation that (reminiscent of Civil War Yankee generals at the first battle of Bull Run in 1861) he invited along a party of dignitaries including Admiral Oldendorf, who had already “run out of target” weeks before, to witness the proceedings from the comfort and safety of their armor-plated podiums. 1/7 stood by in reserve. 3/5 was supported by a company of LVTs to carry the assault troops, an armored LVT(A) company, and a company of waterproofed Sherman tanks supported by UDT 6. The assault got ashore by 0930hrs with no casualties, although the “waterproofing” on the first three Sherman tanks proved inadequate and they were swamped. The Marines proceeded to knock out all beach defenses before turning their attention inland. Ngesebus is mainly flat, covered by scrub, although to the west of the island there was an area of high ground made up of coral ridges and sink holes, reminiscent of mainland Peleliu and now familiar to the Marines. This area was where the Japanese made their main defense line. These defenses though were not mutually supporting like those in the Umurbrogol and so, with the support of tanks and armored LVTs, by the end of the day (D+13) 3/5 had overrun most of the opposition. L/3/5 supported by tanks pushed east, parallel to and past the airstrip to the eastern tip of Ngesebus and across to Kongauru Island while K/3/5 assaulted the high ground and the main Japanese defenses in the west.

Fully waterproofed Sherman tanks of the 1st Marine Tank Battalion preceded by a tank-dozer cross the shallow water between Peleliu and Ngesebus island in support of 3/5. Unfortunately the waterproofing on three of the Shermans proved inadequate and they were swamped, having to be recovered later. In the background can be seen the wooden causeway between Ngesebus and Peleliu partially destroyed in the pre-invasion bombardment.

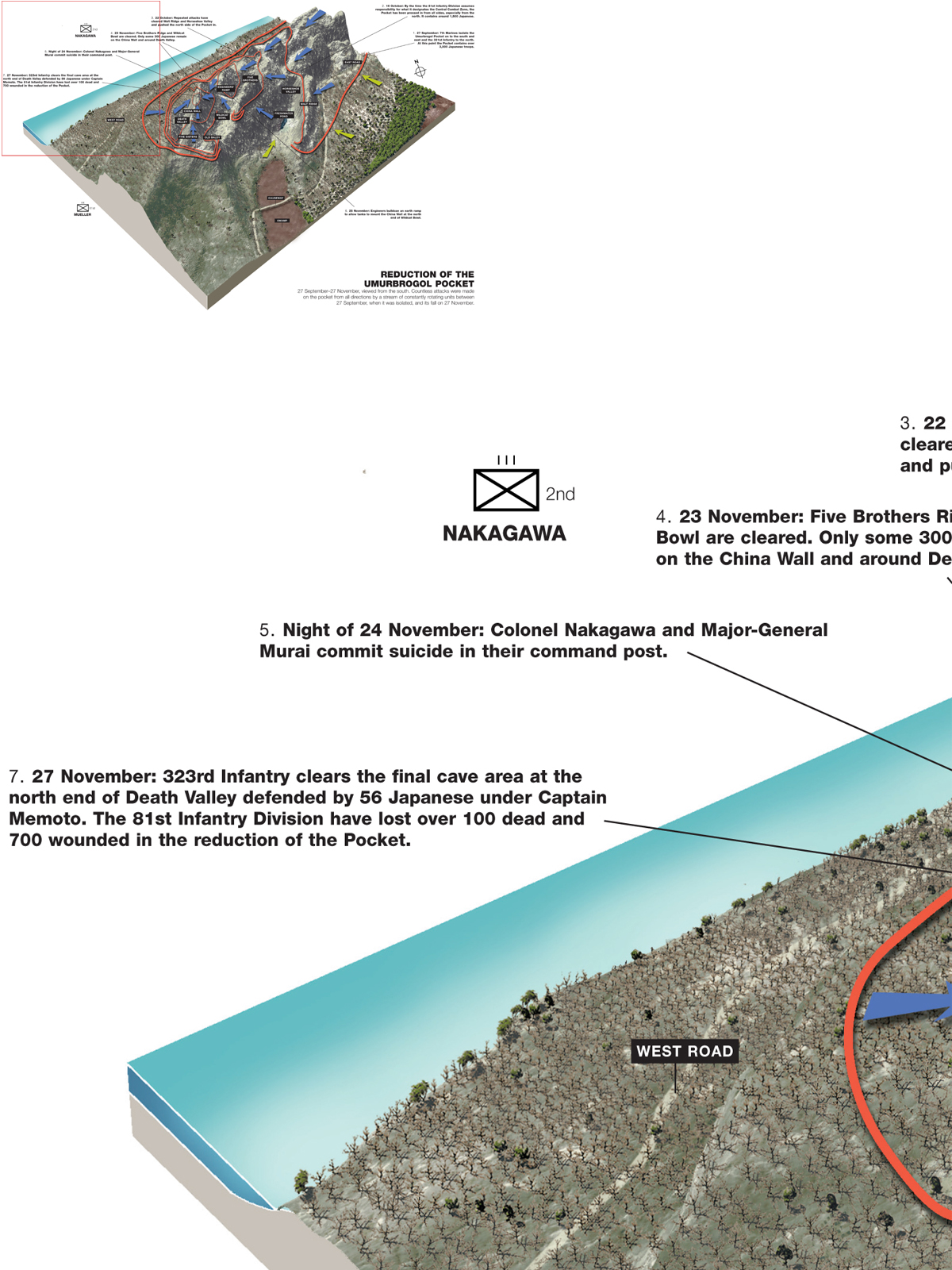

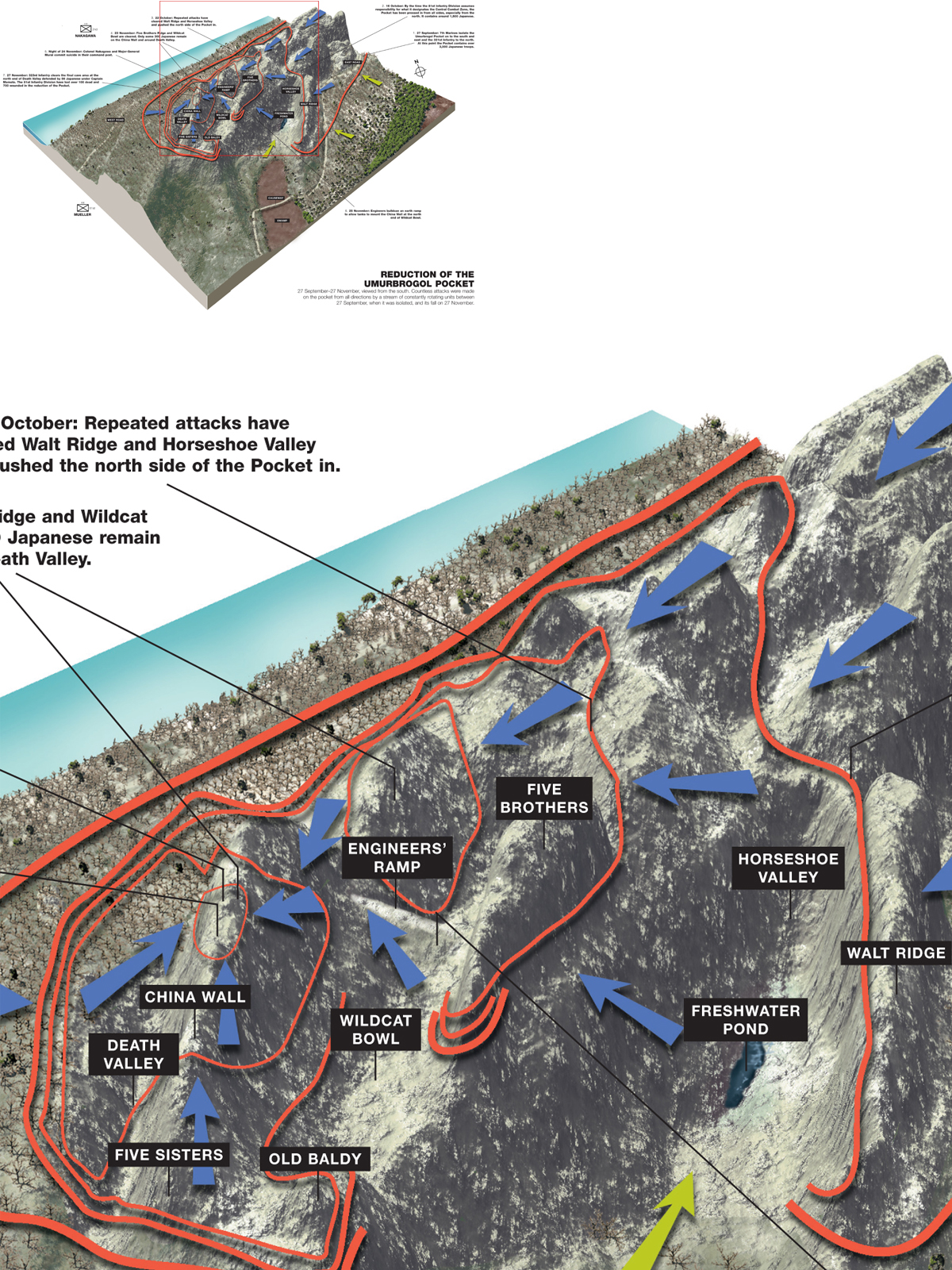

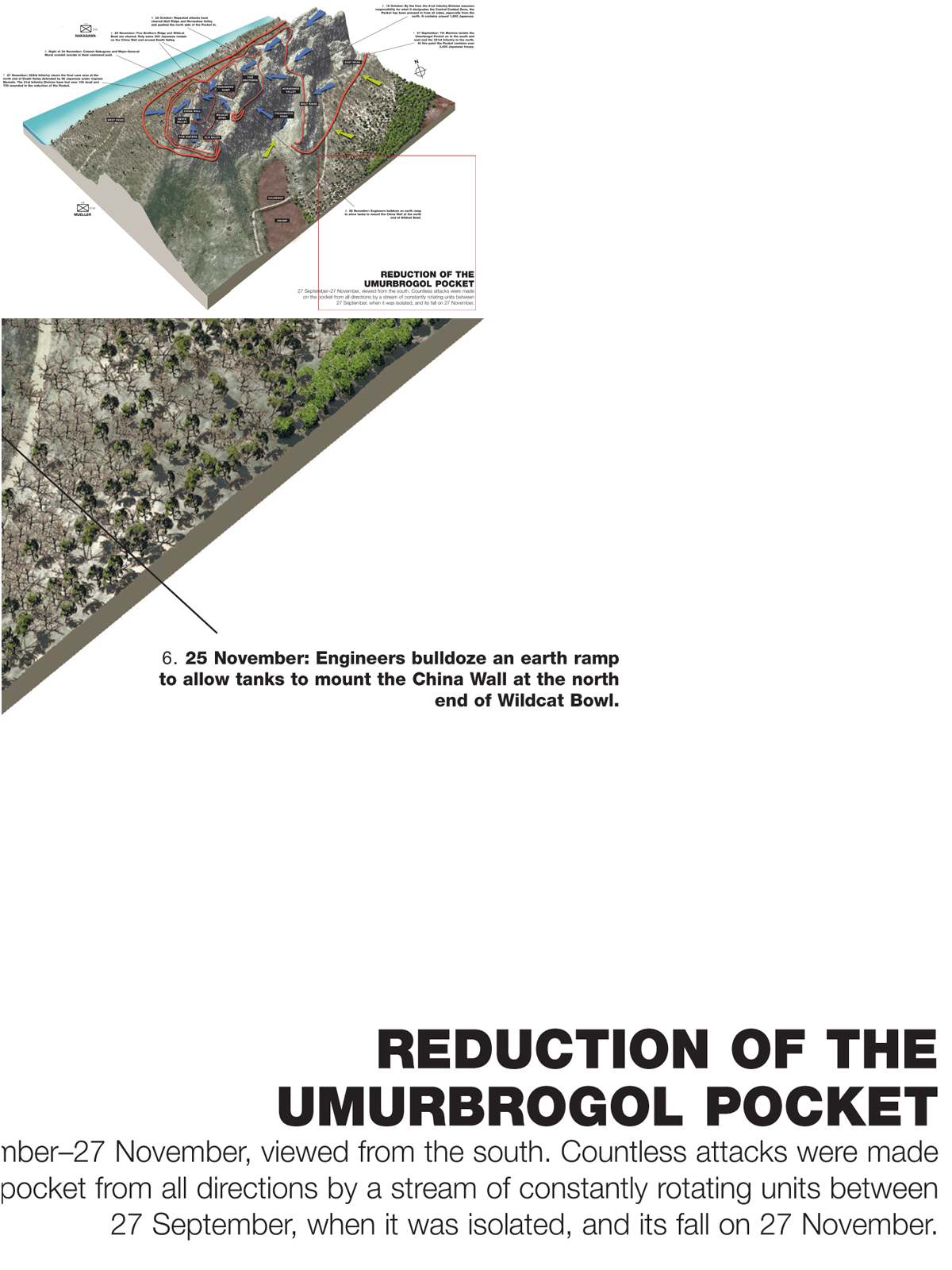

REDUCING THE UMURBROGOL POCKET (pages 54–55)

The incredibly chaotic and broken terrain of the Umurbrogol Pocket proved to be some of the most difficult ground fought over during the entire Pacific war. Countless caves, ravines, gorges, crevasses, and sinkholes honeycombed the coral and limestone hills and ridges of the Umurbrogol Mountains. Flamethrowers, satchel charges, fragmentation grenades, and rocket launchers ("Zippos, corkscrews, pineapples, and bazookas") were required to reduce strongpoints through close assault. Most vegetation had been blasted away and many of the mutually supporting Japanese positions were on inaccessible terrain lacking covered approaches. Often the Marines were forced to carry filled sandbags from the beaches and shove them into protective piles (1) with poles in order to obtain suitable firing positions. A new weapon tested on Peleliu was the 60mm T20 shoulder-fired mortar (2). It proved to be too heavy, parts broke easily, and the recoil too debilitating, with gunners having to be replaced after firing three or four rounds. Its development had been one of several attempts to provide a mortar with capabilities similar to the Japanese 50mm Type 89 (1929) heavy grenade discharger or "knee mortar," as well as provide a weapon capable of direct-fire to attack pillboxes. The 2.36in. M1A1 "bazooka" rocket launcher was widely used at this time and proved to be a much more effective, reliable, and lighter weapon than the T20 mortar. The T20 relied on its high explosive projectile (3) being fired directly though a pillbox firing slit or cave entrance to be effective. It had no penetration effect. The bazooka’s high explosive antitank shaped-charge warhead could penetrate concrete, rock, timber, and sandbag-constructed pillboxes and would be almost as effective if firing through a firing port. A unique unit attached to the 1st Mar. Div. was the US Navy Flamethrower Detachment. It was formed in the States in May 1944 and attached as a test unit to the 1st Mar. Div. in early June. Its single Navy officer and two petty officers trained Marine crewman to man LVT(4) amtracs fitted with Canadian-made Ronson Mk 1 flameguns (4). Also known as the "Q" flame unit, the flameguns had a range of 75 yards with unthickened fuel and 150 yards with thickened fuel. This made the flame amtracs extremely valuable for burning out caves and pillboxes in the Umurbrogol Mountains. It could reach enemy positions out of range of man-packed M1A1 flamethrowers, which had a range of only 40–50 yards. The flame amtracs carried 200 gallons of fuel allowing a flame duration of 55 seconds with unthickened fuel and 80 seconds with thickened. They were normally fired in 3–5-second bursts. Unthickened fuel was straight gasoline while thickened fuel consisted of gasoline mixed with napalm powder or bunker C Navy fuel oil and diesel fuel. The detachment initially had six flame amtracs with a two-amtrac section attached to each Marine regiment. Each section was backed by a support amtrac carrying flame fuel, bottles of compressed carbon dioxide (the flame fuel’s propellant), and a pressure fuel transfer pump. Later a third flame amtrac was added to each section using spare flameguns. The detachment remained in support of the 81st Inf. Div. after the Marines departed. (Howard Gerrard)

D+14 (29 September) was spent mopping up in the western high ground and by 1500hrs Ngesebus and Kongauru were declared secure. Colonel Nakagawa had lost 463 first-rate troops at a cost to the Americans of 15 dead and 33 wounded and all in just 36 hours. Although small pockets of resistance on the islands remained, more importantly Peleliu was now cut off from reinforcement from the rest of the Japanese forces in the Palaus. 3/5 turned the islands over to 2/321 and went into divisional reserve for a well-earned rest. The 321st would have to complete the clearing of these islands and establish security outposts. On 30 September (D+15) MajGen Rupertus declared that “organized resistance has ended on Ngesebus and all of northern Peleliu has been secured,” a statement that brought many a derogatory comment from Marines and soldiers still fighting and dying on and around the north of Peleliu and who would be for many more weeks to come.

On 24 September the Kossol Passage north of Babelthuap was swept of mines and three days later a fleet resupply anchorage was in operation there to support the continued assault.

All of Peleliu but the Umurbrogol Mountains was now largely in American hands and the assault on the Japanese defenses in the Umurbrogol Pocket now took on the air of a Medieval siege.

With the attacks from the north by 2/321 and 3/321 the encirclement of the Pocket was complete whilst the 7th Marines continued to press from the south and west. The Pocket was now down to 1,000 yards by 500 yards in size, not much bigger than ten football fields.

Hill B, which had stalled 321’s attack, was finally reduced on D+11, allowing 321 to continue the assault on the Pocket from the north. Progress was limited but it did allow the Americans to consolidate their hold on the north side of the Pocket.

On D+14 the 7th Marines were ordered to relieve 2/321 and 3/321 in the north but in order to release 2/7 and 3/7 from their holding position on the west of the Pocket the 1st Division command stripped hundreds of men from support units to form two composite groups to secure the north side of the Pocket. They were disbanded on 16 October when the Pocket was compressed further.

Here a flame-thrower gives welcome support to troops attacking a Japanese cave position. Six Navy Mk. 1 flame-throwers were fitted to amtracs for Peleliu and although very effective, the limited maneuverability of the LVT(4) (they were slow and unwieldy out of water) was a problem. The flame-throwers were later fitted to medium tanks, which proved far more effective.

At the same time as these composite units were being thrown together, MajGen Rupertus made a less than sound decision by ordering the 1st Tank Battalion, which still had at least a dozen serviceable Sherman tanks in the field, to return with the 1st Marines to Pavuvu. This astounded other members of his staff with the assistant division commander, BrigGen Oliver P. Smith, later calling it “a bad mistake, the tanks were sorely missed when heavy mobile firepower was so important.”

As if the situation was not delicate enough, nature decided to remind mankind who was in charge by sending down a typhoon, which lasted for three days making it impossible for the Americans to land rations, fuel, and ammunition. Shortages soon developed and transport planes braved the weather to deliver tons of much needed supplies. At least the typhoon did allow the temperature to drop from its usual 110°F to 80°F during the day, but this was soon offset by the dust turning to mud and making vehicle and foot movement difficult in most areas.

1/7 and 3/7 relieved the 321st on D+14 and on D+15 renewed the assault southwards, succeeding in partially taking “Boyd Ridge” and its southern extension Hill 100 (sometimes referred to as Popes Ridge or Walt Ridge) though Japanese defenders remained in caves on the western slopes.

On D+18 the 7th Marines were reinforced by 3/5 (back from Ngesebus) and planned a four-battalion attack from the north and south: the 1/7 and 3/7 from the north and 2/7 from the south with 3/5 making a diversionary attack to the west into “Horseshoe Canyon” and “Five Sisters.” After bitter fighting and heavy casualties the attack secured its objectives with the exception of Five Sisters. Although four out of five “Sisters” were scaled by 3/5 their position became untenable and they had to abandon their gains. On D+18 the assault on Five Sisters was repeated, unfortunately with the same result as the day before! It was also on D+18 (3 October) that the 1st Mar. Div. lost its highest ranking officer killed in action on Peleliu, when Colonel Joseph F. Hankins, Commanding Officer, Division Headquarters Battalion, was killed on the West Road at a point affectionately known as “Dead Man’s Curve.” A mixed convoy of Army and Marine trucks had been brought to a standstill by Japanese rifle and machine gun fire. In an effort to get the convoy moving again, Hankins was seen striding down the center of the road cursing at the drivers to get moving, showing a total disregard for his own safety, and was cut down by a hail of machine gun fire and died instantly.