The synagogue of Budejovice was a large, beautiful red brick building located across the bridge over the River Malse, and set amid chestnut trees. It had two high steeples in front and two great Stars of David over its massive entrance. Inside there was a high ceiling and multicolored stained-glass windows. Families sat in wooden pews, listening to Rabbi Ferda, who led the services from the front. Behind him, the ornately decorated ark held the torah scroll, dressed and adorned with a velvet mantle and silver crown. Rabbi Ferda had lived in Budejovice for years and knew everyone by name. The Jewish community looked to him for leadership and spiritual guidance. Still, at times the children found his sermons too long. With his loud, expressive voice and the stories he told, Rabbi Ferda tried to keep them interested in his services, and in their afternoon Hebrew classes. But he was not always successful.

I’m bored, thought John one day as he sat in the synagogue. It was the Jewish New Year, and most of the families of the Jewish community were packed into the synagogue. Rabbi Ferda’s voice droned loudly from the front of the hall, echoing through the tall archways and bouncing off the ceiling and windows. John looked around, searching for a way out. He spotted his friend Beda Neubauer sitting with his family. Even though Beda was two years younger than John, they were good friends. Unlike the athletic and muscular John, Beda was small for his age, a delicate, smart, and studious boy. Beda also had a great sense of humor. He kept John and his other friends laughing with his funny faces and the stories he made up.

John and his family attended this synagogue in Budejovice. The Nazis blew it up on June 5, 1942.

Next to Beda sat his sister, Frances, and his brother, Reina. Frances was the middle child. She was petite and pretty, with a winning smile and shoulder-length, curly brown hair that she wore in the latest style. Frances smoothed out the front of her red velvet dress and reached down to adjust her shiny black leather shoes. Reina squirmed next to her; he was three years older than Frances, but he was still her best playmate. Together they made puppets from rags, or chased each other around the chestnut tree across the street from their modest apartment.

Beda and his family lived in a building at the entrance of the town – their home was right across the street from the train station, the point where people arrived from other places. Chestnut trees lined the street, creating a thick umbrella of branches in the summer. Each fall, the Neubauer children collected fallen chestnuts, adding sticks and material to fashion toy people. They even made tiny pieces of furniture from wooden matches and twigs. A table covered with a blanket became the stage for their “chestnut theater.”

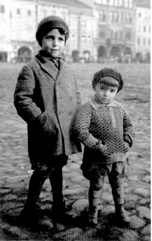

Left: Reina (left) and Frances (right), standing in the central square of Budejovice. Right: Beda.

Other times, the Neubauer children just sat on the stairs in front of their apartment, counting the cars that drove by. “I win!” Frances would shout. “I saw the brown car first! That makes ten cars for me, and only three for you.” Spotting cars was their favorite competition. When they were bored with that game, they waited for the one-armed milkman, who came by every day with his cart full of aluminum milk cans pulled by a pair of large, ferocious-looking dogs.

Before Beda was born, Frances had begged for a sister. She had even left a note for the stork who brought babies, along with a cube of sugar as a bribe. Imagine her initial frustration when this baby boy arrived. “Send it back,” Frances told her parents. “I want a baby girl!” But almost immediately she forgot her disappointment. Beda became “her” baby. She loved to care for him, pushing his baby carriage under her mother’s watchful eyes. Her precious dolls were neglected, left untouched in a corner of her bedroom, while Frances spent all of her time taking care of Beda. When Beda started to walk, Frances took him to the swings in the playground. They walked among the thick bushes and under the tall trees. They played in the sandpit and watched the puppet shows. Later, Frances taught Beda the alphabet, and how to read, before he even started school. “You’re such a bright boy,” she said, beaming with pleasure as Beda read his stories aloud.

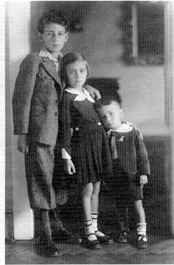

Reina, Frances, and Beda Neubauer.

Beda’s father was an accountant and worked in an office close to their home. But he also worked as a traveling salesman to earn extra money for the family. He used his bicycle to get to his customers, but always made it home in time for dinner. Beda’s mother was a talented knitter, and the family never lacked for warm mittens, scarves, hats, and sweaters. She even sold some of her wares to stores to help with the family income.

The family loved nature walks. Each Sunday they would stroll through the nearby forest, where Mr. Neubauer would identify different birds from their distinctive whistles and chirps. The children would pick blueberries and wild strawberries. On the way back, they would pass the chocolate store. The children found the smell of chocolate through the open windows irresistibly mouth-watering. Sometimes they were lucky enough to get a chocolate treat. For days after, they would remember the pleasure of the sweets.

In winter, the Neubauer children would go sledding on a small hill by the Jewish cemetery. Ski trails were abundant on the mountains and hillsides around the town. Wintertime was special for Frances for other reasons. Her birthday was in December, and Chanukah, the festival of lights celebrated by Jewish people, followed it. At Chanukah, her family would light their menorah – a candelabra with eight candles, one lit for every night of the eight days of Chanukah. The candles were lit from the master candle, which then took its own place at the center of the menorah. Frances’ mother would place their menorah between the double windows in the front of the apartment, where the children could see the reflection of the flickering flames. “Let’s guess which one will be the first to go out, and which one will last the longest,” Frances would say, as Reina and Beda pressed closer to watch the candles burn.

In the synagogue, John stared hard at Beda, straining to catch his eye. Finally, Beda looked up and spotted his friend. Together they nodded silently, agreeing to an unspoken plan. “Father,” said John, in a soft whisper, “I’m just going outside to get some fresh air”. His father nodded. “Don’t be gone long,” he said, and turned back to his prayer book as John stood to leave. Across the room, Beda was having a similar conversation with his father, who likewise nodded as Beda, Frances, and Reina got up together and walked to the back of the synagogue.

Once outside, the children shouted at the top of their lungs, delighted to have escaped the boredom of the service. “Let’s go!” yelled John. “I’ll race you to the park.” And off they ran, across the road and into the park, past the miniature mill, dodging under the draping branches of the huge oak trees. Passing the park benches and dashing along a gravel path, they finally emerged at the playground. The service was soon forgotten as they played hide-and-seek among trees filled with birds that flew as freely as the children played.