On March 15, 1939 – less than eighteen months after seeing President Benes – John woke up to a grim new reality. On that day, hundreds of thousands of Nazi troops marched into towns and cities across Czechoslovakia, claiming the country as part of Germany, under the rule of their leader, Adolf Hitler. In Budejovice, some people were curious to see the soldiers. They came out to watch them enter the central square with their guns and their noisy tanks. But this was nothing like the day when these same people had been out waving flags and greeting their president. On this day, there were no flags and no happy greetings.

The Jewish families in Budejovice were terrified. Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party were known to hate Jewish people. Germany had been suffering terrible economic problems since being defeated in World War I, some twenty years before. A lot of Germans were out of work and struggling to provide for their families. Hitler blamed the Jews for many of Germany’s financial difficulties, and in their desperation many people believed him, glad to have someone to hold responsible for their worries. In the previous months, there had been reports on the radio about hostility toward Jews in Germany. “Something terrible is going to happen here,” John’s mother had said recently, as John listened in on a worried late-night conversation.

Adolf Hitler reviews his troops in Prague, Czechoslovakia on the day of occupation, March 15, 1939.

“We’ll fight against any occupation,” his father had replied.

John’s mother laughed sadly. “How can we fight? And with what? Our country is tiny, and no other country will defend us. Hitler is a madman. We’ve heard on the radio about synagogues being destroyed in Germany, about people being turned out of their jobs. And now I’m afraid it will be like that here.”

“But our friends and neighbors will protect us if something happens.”

Erna Freund had sighed and looked away. She did not believe that anyone would come to their aid. There were some people in their town who, like Hitler, hated the Jews. They hated anyone who was different, or more accomplished, or owned more than they did. They would never defend the Jews of Budejovice. Besides, people were afraid of the Nazis and of Adolf Hitler. And fear could make people do dreadful things.

John had listened to these conversations, but he could not believe there was any danger, even as he saw his parents’ troubled looks. Nothing was going to happen here in Czechoslovakia, he had thought. Not here in our hometown.

“You can’t leave the house today,” said John’s mother, as the news of Hitler’s arrival echoed over the radio.

“I want to see what’s happening,” protested John. “Everyone is out watching the troops. Even school has been cancelled.”

But his parents refused to let him out of the house. John had no choice but to watch from his apartment window, straining to see what was happening outside. He could see the soldiers passing in tight regimental lines, wearing starched uniforms and high black boots. They marched with their legs straight up and down, their shiny boots cracking against the cobblestone pavement. Their arms were held out front in a stiff salute to Adolf Hitler. They were impressive and terrifying at the same time. How can this be? John wondered. How can all these soldiers simply march into my town and take it over?

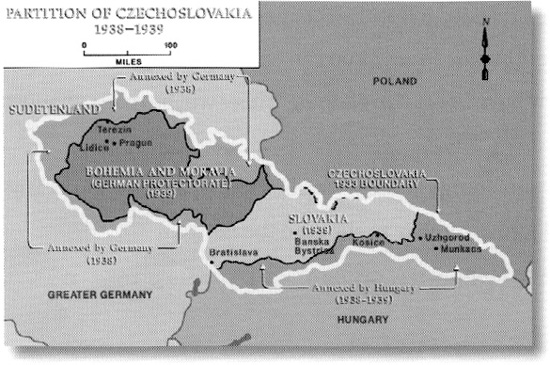

Left: Czechoslovakia in 1933 - before the war. John’s town, Budejovice, indicated by a black arrow, is located just below Prague on the left side of the map.

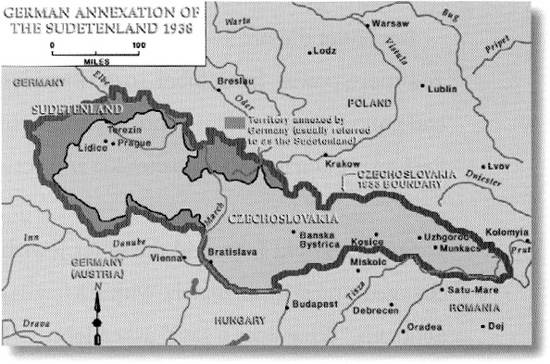

Right: Czechoslovakia at the time of the Munich Pact. The dark area surrounding Bohemia and Moravia, called Sudetenland, is given to Germany in exchange for a promise of peace.

Left: March 15, 1939. Adolf Hitler occupies Czechoslovakia.

A year earlier, Hitler had threatened to wage war in Europe unless a border area of Czechoslovakia, called Sudetenland (pronounced Sue-day-ten-land), was handed over to him. Czechoslovakia couldn’t defend its territory alone – it was such a small country, compared to aggressive and powerful Germany. The leaders of Britain and France held a conference in Munich, Germany, on September 29, 1938 to discuss the problem. None of these countries wanted war. They believed that if they gave Sudetenland to Germany, Hitler would be satisfied. In exchange for Hitler’s promise of peace, that area of Czechoslovakia was turned over to him, by an agreement known as the Munich Pact.

But Hitler did not keep his end of the bargain. He wanted more land and more power. In October 1938, President Benes had resigned and had gone into exile in England. And now Hitler had defied the Munich Pact, marching into Czechoslovakia and occupying the whole country.

For nine-year-old John and the other Jewish people in Budejovice, life changed almost immediately. Within a few days, a notice arrived on John’s doorstep. “What does it say?” asked John, as his father brought the piece of paper into their apartment. Gustav Freund glanced over at his wife and hesitated. “Tell me,” insisted John. “I’ve heard Hitler’s voice on the radio. I can see the soldiers on our streets. You can’t hide anything from me.”

“It’s a list of new laws,” began his father. “There will be many changes now.”

“There are certain things Jewish families won’t be able to do anymore,” continued John’s mother as she read the notice.

“Like what?” asked John.

“Well, we won’t be able to shop in certain stores.”

“You won’t be able to go the public swimming pool from now on,” his father added.

John could not believe what he was hearing. “Can I still go skating at the arena?”

His father sadly shook his head. “But you mustn’t worry, John,” he said. “In a short time, everything will go back to the way it was. You’ll see.”

John nodded and tried not to think too much about the restrictions. He believed his parents. These new rules wouldn’t last. How could they? He hoped that in a few days the soldiers would disappear, and so would all those new laws.

Instead, the rule of the Nazis became stronger each day. Swastikas, the insignia of the Nazi party, appeared on the fronts of buildings, warning Jews to stay away. These dark symbols had the power to exclude Jews from each and every place in town. Along with the swastikas came signs on stores and office buildings, declaring in bold, black German writing, “JUDEN EINTRIT VERBOTEN!” (Entry of Jews forbidden!) The park where John and his friends had played to escape from the synagogue services was now forbidden territory. All Jewish people had to be off the public streets by eight o’clock p.m. Musical instruments belonging to Jews had to be collected and turned over to the Nazi authorities. John’s mother watched sadly as their beautiful piano was removed from their apartment. It left a big empty space in their home and an even emptier feeling in her heart.

John was able to stay in school until the end of that school year, June 1939. But after that date, Jewish children were no longer permitted to attend school. It was also against the law for John to play with his Christian friends. Children who had played with him in the past now kept their distance, afraid of the trouble it would cause their families if they were seen with a Jewish boy. How could they be good friends one day, and turn so cruel the next, wondered John, as one by one, his Christian friends deserted him.

Everyone except Zdenek Svec – the one Christian who was brave enough to remain John’s friend even in the face of these terrible new laws. “Aren’t you afraid to be seen with me?” John asked, as he and Zdenek played one evening in the dark hallway of the school where Zdenek lived.

Zdenek shrugged his shoulders. “We’re friends,” he said. “That’s all that matters to me.”

One day, John went walking on the street. He was careful about where he went, making sure there were no bullies around who might want to beat up a Jewish boy. These days, that was a danger. Across the street, he spotted his former teacher walking toward him. The teacher was a Christian who knew it was risky to speak to anyone Jewish, so John lowered his head as he passed. Suddenly the teacher stopped, blocking his path. John froze. What now, he wondered. But this teacher was not going to hurt him. The man looked around, reached out, grabbed John’s hand, and said, “Remember, you have to be brave.” Then he quickly moved on.

John was stunned. Even talking to a Jewish person was a punishable crime. He felt grateful that this man took such a risk to be friendly to a Jewish child. If only there were others like Zdenek and the teacher, others who were still willing to be friends with a Jew. If there were, maybe things would be different.

The weeks and months dragged by slowly for John. There was nothing to do and so few places to go. He felt cooped up, spending most of his days in his room, or in the courtyard behind the apartment. He kicked his soccer ball against the wall and dreamed of an end to the restrictions. “When will I be able to go back to school, or play on the streets again?” he pleaded to his anxious parents. “You told me things would get better, but they are just getting worse.” His parents turned away and would not look at him. They had no answers.

In Budejovice, as in other cities occupied by the Nazis, many Jews lost their jobs. To save money and help make ends meet, a lot of Jewish families gave up their large apartments and shared accommodations with one another. When John’s father was forced to close his office and his medical practice, and was no longer permitted to work as a doctor, he invited a Jewish family to move in with them. He spent the hours gardening for another Jewish family as a way to pass the time. But if anyone came to call with a medical problem, he was happy to offer his services. These new Nazi laws would not stop him from providing medical care to those who needed him.

In the meantime, the family continued to spend their savings. “How long can we live like this?” asked John’s mother. She was worried that their money would run out and they would have nothing to live on. Luckily, Karel was able to help. He managed to get a job cleaning house for two elderly people. It did not pay a lot, but the small amount of money he earned relieved some of the family’s financial worries.

But everything else kept getting worse. Where would it end, John wondered. When would things go back to the way they had been? How much worse could it get? No one knew the answer. All they could do was wait and hope that life would soon return to the way it had been before the dreadful day when the Nazis marched in.