Karel Freund is the terror of the swimming hole. He shouts and threatens everyone.… We warn you not to ride a bicycle with him.

Karel Freund is the terror of the swimming hole. He shouts and threatens everyone.… We warn you not to ride a bicycle with him.Like all the other Jews in the city, fifteen-year-old Ruda Stadler was frustrated by the rules eroding his freedom, more and more, day by day. He hated the laws and the Nazis who had written them. Most of all, he hated not being able to go to school. Ruda was a tall, strong, and fit young man. He was talented and well-read. And he was smart. “How can we just sit by and obey all these rules?” he asked his sister, Irena. She was only one year older. He could say things to her that he couldn’t reveal to anyone else. “I want to stop this work I’m doing, and go back to school,” he announced defiantly. When Ruda was forced to leave school, he had become an apprentice to a confectioner, learning to make candy. It was nice to have sweet treats to bring home, but he didn’t like his work. He wanted to be in school. He wanted to learn, and to use his mind.

Irena smiled at her brother. She admired his feistiness. “Ruda, you think too much,” she said. “Why can’t you just follow the rules and stop questioning everything?”

“But you hate what’s happening as much as I do,” countered Ruda. “Do you like the fact that we had to change apartments because our father isn’t allowed to work?” Like the Neubauers and many others, the Stadlers had been forced to move out of their large flat to save money. They now lived in a single basement room.

Irena shook her head.

“Do you like the work you do?” he continued, confronting his sister. Irena was attending classes where – like Frances – she was learning dressmaking. But she hated the fact that a real education was being denied to her. Even though she was an excellent, creative seamstress, she could not take pleasure in her skill.

“You know I don’t,” she said, sighing. “I want to be back in school, just like you. I don’t like anything that has happened to us and our friends. But there’s nothing we can do about it.”

That wasn’t a good enough answer for Ruda. There had to be something he could do. He was not willing to give in to these endless new laws. He didn’t like it when grown-ups told him to follow unfair rules that made no sense. He had to find a way to speak out. But how?

In the meantime, the summer playground at the swimming hole was a welcome retreat, a place for Ruda to relax and, at least for a short time, abandon his frustrations. Like the others, he had become a frequent visitor. As soon as he finished his work, he would head there. Volleyball was his favorite sport. He was good at it, and admired by all the other players. He was nicknamed “Digger” because of the way he received a ball that was served to him. Placing his hands together at waist level, he would scoop or “dig” the ball up from down low.

Meeting together every day, the young Jews of the city felt connected to one another. Ruda could see that, and he wanted to find a way for them to strengthen their bond, and feel even stronger. There must be more we can do here, he thought one day, as he lay in the sun close to the river. Behind him, the younger children were playing a wild game of soccer, running from one end of the field to the other, shouting and shoving one another playfully. Playing sports is fine – but how long can we continue to just play, thought Ruda. We’re smarter than that. We may not be able to go to school, but everyone here has a brain and should use it well. Besides, the warm summer days will soon end and it will be too cold to come here. Then what will we all do every day? How will we stay connected to each other?

And then, one day in August 1940, the answer came to him. Ruda had been a talented writer in school. Reading and writing stories had been the activities he enjoyed most. Writing would be the perfect way to continue to use his mind, to provide an outlet for his energy and creativity. But this time, he would write not only for himself. He would write for the other young people at the swimming hole. He would start a newspaper – a magazine that would prove that Jewish youth could do more than just play. He would encourage the community, especially the children, to band together and use their imaginations.

The next time he came to the playground, he brought an old typewriter from home. Luckily, it still worked. He also brought some paper. He took them into the old shack, and sat down and thought. First of all, he wanted to introduce the newspaper to the others and explain its purpose. He needed to convince them that there was a better way to spend their time.

He sat down at the typewriter and wrote this introduction:

Since we’ve exhausted every type of entertainment that can be done at our beautiful swimming area, I want to outline a few words about those who come every day, and add a few witty remarks about them.

Then he went to work, listing the names of all the young people who came to the swimming hole every day, and trying to think of something interesting to say about each one of them.

Karel Freund is the terror of the swimming hole. He shouts and threatens everyone.… We warn you not to ride a bicycle with him.

Karel Freund is the terror of the swimming hole. He shouts and threatens everyone.… We warn you not to ride a bicycle with him.

John Freund is better than his brother, Karel, though he is a menace to others; he prevented an accident on a nearby railroad bridge.

John Freund is better than his brother, Karel, though he is a menace to others; he prevented an accident on a nearby railroad bridge.

Anka Frenklova likes to eat, as demonstrated by her spreading waistline.

Anka Frenklova likes to eat, as demonstrated by her spreading waistline.

Irena Stadler has become like a mother to all the girls, both small and older.…

Irena Stadler has become like a mother to all the girls, both small and older.…

Dascha and Rita Holzer are faithful visitors to the swimming hole.…

Dascha and Rita Holzer are faithful visitors to the swimming hole.…

Herta Freed is a clever girl who knows many languages.…

Herta Freed is a clever girl who knows many languages.…

Suzu Kulkova is an easy-going girl whose heart belongs to Uli, the soccer player.… She is also an excellent rugby goalkeeper.

Suzu Kulkova is an easy-going girl whose heart belongs to Uli, the soccer player.… She is also an excellent rugby goalkeeper.

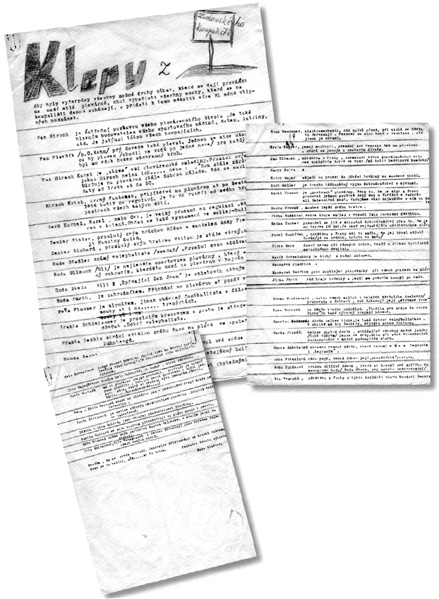

The first edition of Klepy was three pages long. Ruda listed the names of the young people who came out to the swimming hole and wrote something witty about each of them.

Ruda worked alone, telling no one what he was doing. He kept to himself, writing and thinking about his mission. He wondered if people would take it seriously. He even wondered if some people might be offended by his remarks about them. In his first editorial, he wrote:

This newspaper was created by Ruda Stadler. I’m the only one responsible for its content. If people don’t like it, or are insulted, they should contact me.

I’ll write one edition of the paper and see what happens, he thought. If no one likes it, I’ll forget about doing any more. He gathered information like an investigative reporter, and compiled what he learned into three typed pages.

Next, he gave some thought to a name for the paper. He wanted to keep it light. Finally, he decided to call it Klepy, Czech for “gossip.” It was the perfect title.

On August 30, 1940, Ruda produced the first edition of Klepy. He made only one copy. It was difficult enough to do that; it would be impossible to duplicate it. He decided that he would circulate the newspaper to all the young people at the swimming hole, and see what their reaction was.

“Klepy” is Czech for “gossip.” This drawing of a gossipy woman was on the cover of most editions.

A sign-off sheet accompanied the paper. When people finished reading Klepy, they were to sign their names on the sheet, add a comment or two, and pass the newspaper on to someone else. In this way, they would all have a chance to read Ruda’s bold new experiment. As for Ruda, he could only sit and wait. Would they like his paper? Would they be irritated – or worse yet, bored? What would they say?