As August gave way to September, and a third edition of Klepy was published, the children needed the newspaper’s optimistic message of friendship and camaraderie more than ever. Adolf Hitler’s power was increasing and his persecution of Jews was escalating. His armies were spreading across Europe, defeating country after country. At times, it appeared that nothing could slow the Nazis down. Each evening John listened to radio broadcasts with his parents, and the news kept getting worse. Italy and Japan had teamed up with Germany, and so had Hungary, Romania, and Slovakia. Denmark and Norway had been defeated. France, Belgium, and Luxembourg had fallen, and so had the Netherlands. Britain was fighting back bravely against endless bombing raids. Canada, Australia, and New Zealand were all taking Britain’s side. But the United States was refusing to join the war.

John’s parents received letters from family members in other countries. They talked about cities in Poland and Germany in which large sections were being blocked off. Jews were being ordered to move to these “ghettos” – to leave their homes and belongings behind, and move into cramped apartments, often sharing tiny spaces with two or three other families. Food was scarce inside the ghettos. And even if food had been available, money was in yet shorter supply. Children and grown-ups became sick. The elderly were especially at risk. And each day, more and more Jews arrived from neighboring towns and villages, and the crowding, the shortages, and the health problems grew worse.

“How much longer can this go on?” John’s mother asked one evening, as she listened to Czech-language news from Great Britain on the shortwave radio. The Czech radio station was in the hands of the Nazis, of course, but the British translated the news into all the languages of Europe, to tell people the truth, and reveal Hitler’s lies.

John’s father nodded. “The news from other countries isn’t good. But at least we’re all together here, and still in our own home, even if we do have to share it. Think of the families who have had to leave their homes in Poland and Germany, and move into the ghettos.”

“That could never happen here, could it?” Mother asked. Father didn’t answer. “But what about money?” she continued. “At this rate, our savings will be gone in no time. Then what will we live on?”

“We have to get used to eating less,” he replied. “Less meat, and bread with no butter.” He saw the look in his wife’s eyes and added quickly, “Just for now. I’ll work again soon. I’m sure of it.”

John turned away. He hated to see his father out of work and his mother so unhappy. But he didn’t want to think about war, and worse things happening in other countries. Surely there would never be ghettos in Budejovice! Even though certain places were forbidden to Jews, John could still walk on the street and play with his friends. Although the rules restricting Jewish families were increasing, the war didn’t scare him. He was young and spirited, and he wanted to play sports with his friends. He even had a job to do every day.

His job was to deliver messages to the city’s Jewish families. He rode his bicycle from home to home, leaving a notice with each household. The notice instructed the families to list all of their properties and belongings for the Nazi authorities. They were ordered to write everything down: how many rings, bracelets, or pieces of silver they owned; how much land was theirs; the name and value of their business.

It had never occurred to John that, by collecting information about Jewish families, he was in fact helping the Nazis. “Don’t you realize that you are helping to deliver this information into the hands of the enemy?” asked Beda one day, as John stopped by Beda’s house.

The last thing he wanted was to collaborate with the enemy. But it was true that he had been told to do this work by the Kile, the Jewish council – and the Kile’s orders came from the Nazis. Still, John had to continue his job. He tried to make the best of it. He even sang songs to himself as he rode door to door. But before long, his dilemma was over. His bicycle, like everything else, had to be turned over to the Nazis.

Now it was time for John and the other children to return to school. Fall was approaching, and soon it would be too cold to go to the swimming hole. Even though regular school was forbidden to Jewish children, it was important for them to have some way to continue their education. And so, in September, they began classes with Mr. Frisch.

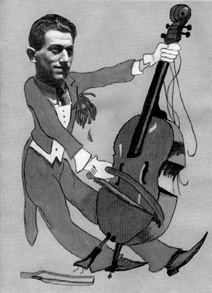

Mr. Joseph frisch, the teacher (an image from Klepy).

Joseph Frisch’s family had a coal business in town. He was a talented young Jewish man who, in his spare time, played bass in the town orchestra. He was also studying to be a teacher. When school was no longer permitted for Jewish children in Budejovice, Mr. Frisch arranged for groups of children to come to his home for lessons.

The classes were small, only five to six children at a time. School started early, at about eight o’clock in the morning, and continued until about two o’clock in the afternoon. Children between the ages of eight and thirteen attended this school five days a week, and were taught by Mr. Frisch as well as some older boys and girls who were there to help.

Mr. Frisch was happy to have this opportunity to continue to teach. He had set up small desks in his living room so that the children could feel as if they were really in school. And the lessons were difficult. The children studied algebra, Latin, history, and grammar. They had assignments to do after school and homework on weekends.

The first time John entered Mr. Frisch’s home, he spotted Tulina sitting at another desk. At least having her here will make things more interesting, he thought. As he glanced around the room, he was happy to see Beda there as well.

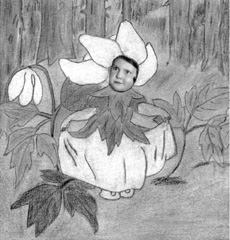

John’s first girlfriend, Tulina (Rita Holzer), from Klepy.

There in Mr. Frisch’s living room, the children were even able to continue their religious education. Rabbi Ferda came once a week to teach Hebrew and Jewish studies. Before the war, most of these young students had not received as much Jewish education as they were now receiving. There was no more hope of skipping classes.

Sometimes, Rabbi Ferda could be gloomy about the future. “Our fate through the ages is like a red thread of danger, weaving its way through time,” he preached. Whatever did he mean by that, wondered John. Of course times were tough. But surely things would get better, and the war would end soon. I can’t wait for that to happen, he thought. And I can’t wait to get out of this class! Secretly, he longed for each day to end.