In those early fall days of 1940, when John and his friends had returned to school, one of the few things they had to keep them connected was Klepy. The newspaper was doing what Ruda had hoped. It was serving as a link for the Jewish children of Budejovice, the one place where their thoughts and ideas could come together and be shared with everyone else. It was even more important now that they could no longer meet at the swimming hole. John and his friends read the stories from the newspaper aloud to one another, and then looked forward to the next edition.

On October 6, 1940, the fourth edition of the magazine was produced. By now, Klepy had a beautiful color cover, drawn by a young artist who went by the name of Ramona. Ramona was really Karli Hirsch, who was now one of the editors, in charge of the drawings. His pictures were becoming a main feature of Klepy. Often, he took real photographs of young people in Budejovice, and added his own illustrations, transforming these photos into lively cartoons and comic strips. And how the magazine had grown! The fourth edition was eight pages long, and included a sports column, poetry, and detective stories.

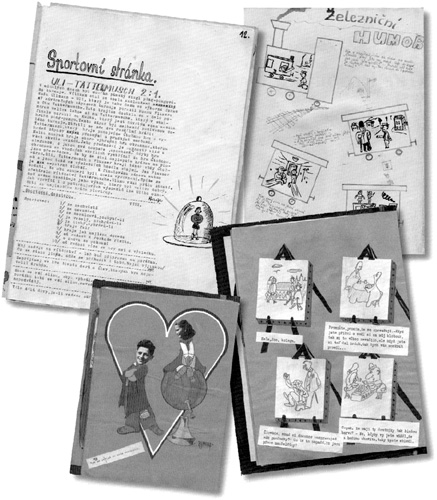

Clockwise from top left: Klepy regularly included drawings, stories, a sports report, comics, and a humor section. This sports column lists the ten rules of sportsmanship. The humor page has jokes about trains, and the comic strip also includes jokes and riddles. Bottom left: Karel Freund (left) and his girlfriend, Suzie Kopperl. The caption reads, “You are the only one in the world.”

The reporting team was also growing. Rudi and Jiri Furth had been part of the editorial group from the beginning. Reina Neubauer was beginning to write poems for the paper. Dascha Holzer, Tulina’s sister, wrote stories, along with Suzie Kopperl. Suzie was the girlfriend of Karel Freund. She had already written several poems for Klepy, including one about Karel. Other writers, like Jan Flusser and Arnos Kulka, regularly contributed to the newspaper.

Ruda knew that Klepy was an important lifeline for the Jewish youth of Budejovice, as well as the whole Jewish community. It was important to him personally as well. When he worked on Klepy, he could almost overcome the shadows over his life. But keeping it going week after week and month after month was hard work. He began each day by going to work at the candy factory. Irena brought him lunch there, often rushing from her own work as a seamstress to bring food to her younger brother. When his workday ended, he met with Jiri, Karli, and the other writers to work on Klepy. They were very careful to finish their meetings before the curfew for Jews began at eight o’clock in the evening. But sometimes a few of them worked into the late hours of the night, and then snuck home through the darkened streets, wary of the patrolling Nazi soldiers.

Usually, they all met at Ruda’s apartment to organize the newspaper. He had his typewriter and whatever paper and other supplies were available. When those ran out, they pooled the little money they had to buy more paper and pencils. Luckily, Jewish people were still able to shop in certain stores at certain times of the day.

“What are we going to write about this month?” Ruda asked his reporters, as they sat around the table in his family’s small flat, planning the fifth edition. One bright light burned above their heads, casting dark shadows across their intent faces. Together they pored over the poems, drawings, and jokes that had been submitted. Sometimes, they read the stories aloud to one another, eager for someone else’s opinion, or unsure about exactly where to place the story. “These stories are fun,” said Ruda thoughtfully, as he listened to Jiri Firth reading one. “But I think we need to write about serious issues as well.” Ruda believed that, in addition to being entertaining, Klepy could also become a forum where important ideas were discussed.

“We must be careful,” countered Reina Neubauer. “We don’t want the Nazis to find out too much about us. If they think this is a political magazine, they might shut us down.” Reina was a serious-minded young man who loved to write stories. Before the war began, he had often helped his sister with her writing assignments. As a result, Frances had often received high grades that she had not quite earned on her own.

The reporters looked over the articles for that edition and sorted out their tasks. Ruda always wrote the editorial; that was his job as the creator of Klepy.

“We need another editorial that encourages people to write contributions for us,” said Dascha Holzer. She was a bright, self-assured girl with a wild head of curly, brown hair.

Ruda nodded and sat down at the typewriter. “To all readers,” he wrote. “Obviously your contributions have diminished. We understand that the swimming season is over. Therefore, interest in our paper may have gone down. However, we must keep Klepy going.” He sat back, satisfied with his opening.

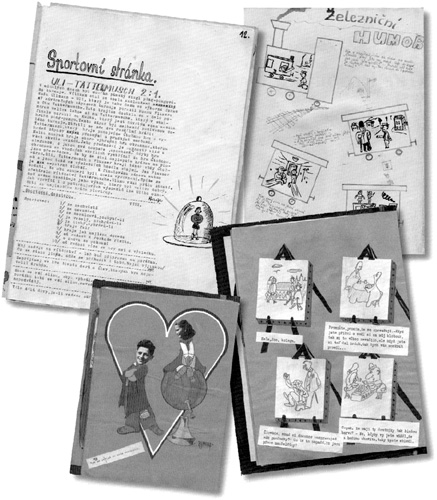

Top: In this editorial (Uvodem), Ruda appeals to readers to contribute articles to Klepy. Bottom: At the end of every edition, in a section called Listarna (editor’s comments), Ruda thanked those who had contributed articles.

Ruda lived on this street in Budejovice, pictured today.

Tirelessly Ruda and his friends sifted through the many jokes and word puzzles that had been submitted, narrowing down the list of items that would appear in the next issue, in the humor section. Poems were also popular, so Ruda selected the ones that would complement this edition. Stories were next, along with a sports column. Now that it was fall, and the sporting events had ended, the sports column was a popular reminder of warmer days.

The last step was to end the magazine on a high note. This was also Ruda’s job. He was in charge of writing a section called “Listarna” (editor’s comments) at the end of every edition, in which he thanked those who had submitted stories and articles. He also added a comment or two about the various contributions. He knew it was important to thank everyone for writing. That was the only way to encourage others to submit their work. And more submissions were needed to keep the newspaper going.

There was so much to think about. They worked feverishly, choosing where the pictures would go and creating headings and captions. Finally, it was time to start typing. Ruda bent over the typewriter and pecked out the handwritten stories and articles. No one noticed the time passing as the pages were typed and retyped. Pictures were pasted in to enhance the stories. Each page had to be proofread several times. Ruda wanted no mistakes in Klepy.

Finally, Ruda stood up and smiled, and shook hands with his friends. They slapped each other on the back, hugged, and congratulated themselves. The fifth issue of Klepy was ready to be circulated.