“It’s here!” yelled John, bursting through the door of his apartment with another issue of Klepy in his hands.

“Wonderful!” his mother responded. “Let me have a look.”

John shook his head. “I’m first,” he said, and moved off into a corner where he could read the newspaper uninterrupted. This edition of Klepy contained his first article, and he wanted to look at it by himself. He thumbed through the pages, pausing to read some of the stories. His mother stood nearby impatiently, wanting her turn at the magazine. Finally, John turned a page and there it was.

HOW MY FATHER, A DOCTOR, FIXED MY HEAD

By John Freund, 10 years old

“Mom, please give me money. I need a haircut.”

“You better go to Dad, son. He will give you some.”

So I went to see my father. He was sitting at a desk. “You know, these are bad times, and we don’t have much money. As a doctor, I’m used to examining heads. I will cut your hair and shave your neck as well.”

John’s first article in Klepy, “How my father, a doctor, fixed my head.”

And so it began. Dad took the knife and began to shave the back of my neck. That was not bad. Then he took a pair of scissors and started to hack at me. You would not believe what a doctor can do … “Ouch!” I cried out suddenly as my father cut into my ear. My mom, in the kitchen, heard the cry and came running. She opened the door and almost fainted. I had almost no hair left. I ran to the mirror. For a moment, I did not know whether to laugh or cry. My mother began to shout at my dad, until he gave in and handed me a quarter for the barber.

When I entered the barbershop and took off my cap, the barber screamed, “What kind of artist cut your hair?”

Fortunately, the barber was able to fix what the doctor had destroyed!

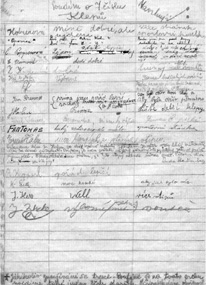

John was thrilled to have become a contributing reporter for Klepy. He quickly turned to the back of the paper, to the sign-off sheet, to write in his name and his comments. He glanced down at the comments that were already there. Most people loved Klepy, and their comments were full of high praise. Some people had suggestions for what they wanted to see in the newspaper. Some even criticized the paper and its articles.

John took a pen and began to write: “First class. The newspaper gets better and better. Soon there will be one hundred pages, which is good. I can’t wait for that to happen.”

Every edition of Klepy included a sign-off sheet asking readers to sign their name and comment on that edition. On this sheet John writes, “First class. The newspaper gets better and better. Soon there will be one hundred pages, which is good.”

Then he passed the newspaper to his parents so that they could have their chance to read it, and to record their comments. They laughed when they read the article about the haircut.

“I never knew you were such a wonderful writer,” his mother said, proudly.

“How can I walk down the street after what you have written about me?” joked his father.

Any excuse to laugh felt good these days. Laughter was a way to forget the cruelties of the war, a way to feel that life was normal. Nothing else about life in Budejovice felt normal anymore.

It was becoming increasingly dangerous to walk in the streets, and Jewish people were forbidden to enter certain parts of town at all. Arrests were becoming more commonplace, as Jews suddenly vanished off the streets. Where did these people go, John wondered, as his parents whispered about the disappearance of this acquaintance, or that colleague.

“Will we be arrested?” John asked his parents. “Or crammed in some little shack?” he added, remembering what he had heard about the ghettos in Poland and Germany.

“No,” his father said quickly. “We’re safe here in our home.”

When Ruda heard about these new arrests, he felt less certain about their safety. He believed that it was only a matter of time before the Jews in Budejovice were treated as badly as those in other cities. How could he believe otherwise? Since the first anti-Jewish laws had been proclaimed, the situation had kept getting worse and worse.

All the same, he believed in the strength of his writing, and in the power that came from Klepy. As each edition of the newspaper was published, he continued to appeal to the young people to write more. And they did. They contributed articles, poems, and drawings. Each edition was longer than the one before, and more elaborate. The newspaper grew from five pages to fifteen, and then to twenty-five. The young people wrote despite the restrictions placed on them, and despite any fears they might have. They wrote to reclaim their freedom.

That was what Ruda had really done by creating this newspaper. He had pulled the Jewish community of Budejovice together, and given them something to fight for.