Ruda Stadler was also wondering about what to take to Theresienstadt. He stared at the box of newspapers: twenty-two editions of Klepy, along with twenty-two sign-off sheets. He thumbed through the box of papers and picked up the very first edition, three simple pages of chitchat. He marveled at how the magazine had grown and developed in two years: from three pages to as many as thirty pages; from childish gossip to mature articles and drawings, jokes and poems. His editorials were there, along with the articles written by so many Jewish children of Budejovice. They had been underground reporters, and he had been their leader.

“Do you believe we really did this?” he asked his sister, Irena, when she entered his room. “Every day for the past two years, we’ve been told that we can’t do this or that, we can’t go here and there. And yet we managed to create something so special.”

“You’re the one who did it,” Irena replied proudly.

“No,” insisted Ruda, “everyone contributed. Klepy belongs to all of us.” He picked up the box of newspapers. It was heavy.

“What are we going to do with these while we’re away?” he asked, remembering his pledge to keep the newspapers safe.

“We could take them with us,” she suggested.

Ruda shook his head. “No, I don’t think that’s a good idea.” The collection of newspapers was heavy. He needed the space in his suitcase for clothing and other supplies.

“Maybe you could divide them up,” she continued. “Give a few issues each to a number of the reporters. I’m not sure keeping the collection together is the best idea.”

Ruda thought about that, but then shook his head again. “No. Whatever happens to us, I believe the collection should stay together. Somehow, that feels like the right thing to do.” He paused. “We’re going to have to find a place to leave these while we’re away.”

“There’s no place to hide them in our apartment. And we can’t leave them here in the open,” she said. “We don’t know what will happen to the things in our home while we’re gone.”

“I wish I could take them with me,” sighed Ruda. “But I know that’s impossible.” He paced through the small apartment. “Where can we leave the newspapers so they will be safe? Who can we trust to hide them?”

Ruda and Irena finally came up with a plan. Their former housekeeper, a Christian woman named Thereza, had remained a friend, even after it became illegal for her to work for a Jewish family. She had left the Stadlers tearfully, promising to assist them in the future. The time had come to ask for help. Leaving the magazines with her was the only solution. Ruda trusted her to keep Klepy safe.

He gathered up the newspapers into a big bundle and left his home. He ran quickly through the streets of Budejovice, careful to avoid any soldiers who might be out on patrol, ducking in and around buildings to avoid being seen. Finally he arrived at Thereza’s home, anxious and out of breath.

When she saw Ruda at the door, Thereza pulled him quickly into her home, glancing around nervously to see if anyone had noticed him. It was dangerous for her to be seen with a Jewish boy, and even more dangerous to be hiding this Jewish newspaper. But when Ruda explained what he needed her to do, she did not hesitate. “I’ll hide them, Ruda,” she promised. “No one will find them in my home. And they’ll be here waiting for you when you return.”

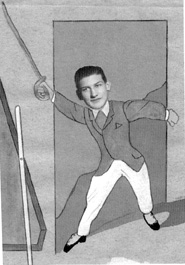

A photo/drawing of Ruda as the fearless leader, from Klepy.

“I’m so grateful,” Ruda whispered.

She shook her head. “It’s the least I can do for a friendship that has lasted so many years.”

“I’ll come back for them,” Ruda promised, as he handed over the bundle of newspapers – two years’ worth of work, imagination, and resourcefulness. He felt as though he was handing over his past, his life. As much as he wanted to believe that he would come back home, he was deeply uncertain about his future. Even as he vowed to return, his voice was shaky, and he felt sad and empty as he walked away.

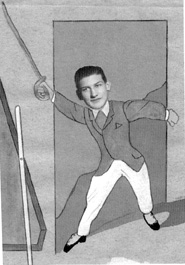

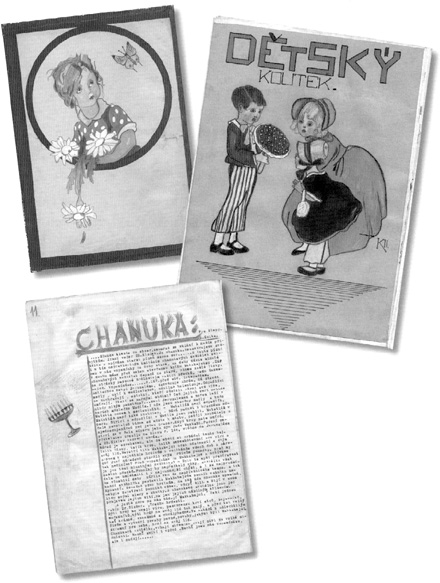

Top: Drawings from Klepy. Bottom: In this edition, an article about Chanukah includes the following passage: “Be proud of your people, so small yet so big, beautiful, and praiseworthy. Chanukah urges us to do good, noble deeds, and have strong character. The Chanukah candles shine back to the great past. Let them shine forth, so that while bringing back a memory, they also bring forth hope.”