John eventually found himself in Barracks L417, the house for boys under the age of sixteen. Because he was older, Karel went with their father.

The first time John entered the dormitory, he was terrified. He already missed his parents and his brother. There were forty boys in the room, crammed into a very small space, but John felt alone.

As he stood there, uncertain and afraid, a young man walked up to him and reached out his hand. “Welcome,” he said. “My name is Arna. I’m looking forward to working with you.”

Almost immediately, John felt himself relax. Young Jewish men and women lived in the children’s barracks as house leaders. Arna, a tall, good-looking young man, was the leader of this boys’ room.

John had to adjust to a new reality of life in this harsh place. Three times a day he stood patiently in a long line, waiting to receive his tiny portion of food. In the morning, there was weak coffee. At noon, prisoners received some watery soup – on good days there was a potato in it, or a dumpling floating on top. For supper, there was more soup and a small bun. Hunger pains clawed at John’s stomach, until they became so familiar that he couldn’t remember what feeling full was like.

In the barracks, the bunk beds were piled three high, to enable forty boys to sleep in the crowded room. It was dirty and difficult to keep the bugs and rodents away. Soap was a treasure, hoarded for the rare times the boys had the opportunity to wash in cold water. With no hot water for washing, lice bred in the boys’ clothing, hiding in the seams, biting them and spreading disease. Prisoners became ill on a daily basis.

In another room in the boys’ barracks, Beda was having his own problems. Shortly after arriving in Theresienstadt, he had contracted scarlet fever, a serious disease. It had begun with an infection in his throat and had led to a high fever and a rash across his body. Left untreated, scarlet fever could be fatal. Fortunately, Beda was treated in a small hospital and within a few weeks he recovered. But the disease left him weakened and frail.

Beda’s sister lived in the girls’ Barracks L410. Even though their buildings were close, Frances and Beda rarely had a chance to see each other. Frances spent her days working. Her first job was in a bakery, sorting through the moldy bread that was put aside for the Jewish prisoners. She hated the work. The hours were long and the conditions were terrible. Back at home, this rotten bread would have been thrown out in seconds. But here in this prison, hunger drove Frances to steal pieces of the bread for herself and her family. You can eat anything when you are starving, she realized.

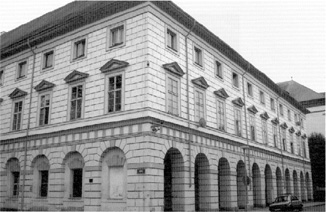

The boys’ dormitory in Theresienstadt as it looks today. It is currently the Terezin Museum.

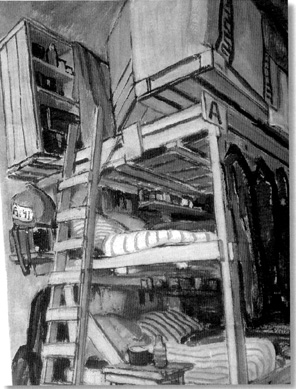

Bottom: An unknown artist’s rendition of the bunk beds in a barracks room in Theresienstadt.

Frances lived in the girls’ dormitory in Theresienstadt. This is how it looks today.

Frances’ skill as a seamstress became useful in Theresienstadt. After several months, she was transferred to a sewing room in the basement of the girls’ dormitory. There she mended and patched uniforms, and made toys for the children of the soldiers. She carefully stitched pieces of cloth together to make stuffed animals. Jewish children will never see these toys, she thought sadly, as she looked down at her handiwork.

At the end of a long workday, she climbed the stairs to the crowded room that she shared with nineteen other girls. Here she collapsed, exhausted, on her bunk bed, trying to ignore the fleas and bed bugs that bit her. I miss my home, she thought desperately. I’m tired and hungry, and I miss my family. Does anyone outside these walls care at all about what is happening to us?