In another part of Theresienstadt, Ruda and Irena were struggling to survive. Too old to be in the boys’ barracks, Ruda had an exhausting job working in the bakery, with long hours and terrible conditions. This isn’t a bakery at all, he thought, remembering the wonderful smells of the bakery at home. He tried to keep memories of home as far away from his mind as possible. But every now and then, he paused and recalled the days when he and the others had worked on Klepy. He had not written anything since he had stepped down as Klepy’s editor. It was as if that part of his life was finished.

Irena had been assigned to work with the young girls, many of whom were orphans. Their innocent faces longed for comfort, and Irena loved them and looked after them as if they were her own children. She called the girls tetky, a Czech word for “little aunts,” and they lovingly and jokingly called her strejdo, which means “little uncle.” But despite their smooth young faces these girls were frightened, and Irena could do little to reassure them.

A sketch of Ruda working in the bakery in Theresienstadt.

Each day, Irena received a small amount of bread to share with the children she cared for. “You cut the bread, strejdo!” the girls would shout. “Only you can cut the slices thin enough. That way, we can pretend there is more for all of us.”

Irena would cut the bread into paper-thin slices and hand them to the starving children. “Here, my tetky,” she would say. “Let’s pretend this is a feast.” She would smile, but inside she would wonder and worry about how long they could stay alive in there.

Ruda bent over the hot bakery ovens, hoping he would see Irena later that day. He visited her as often as he could. It was always difficult with family visits restricted to several hours once a week, but that did not stop him. He was smart and resourceful. He snuck out late at night, traveling through the dark streets to Irena’s barracks, dodging the guards on patrol with their fierce dogs.

“How are you managing?” she asked when he met her that night. She worried so much about her brother, who looked pale and thin.

Ruda shrugged his shoulders. “I’m still strong,” he replied. “And you must stay strong as well.” He reached into his pocket and pulled out a small loaf of bread that he had managed to sneak out of the bakery. “Here,” he said. “I’ll bring you more whenever I can.

“Have you heard the rumors?” he continued. “People say the transports leaving from here are taking prisoners to other concentration camps, where they are being killed.” Each day, thousands of prisoners received notice that they were to be sent to an unknown destination in the east. No one wanted to talk about where that might be.

Irena nodded. Of course she knew about the transports to the east. But like most of the prisoners in Theresienstadt, she tried not to think about them. Besides, these days she did not want to talk about transports or death camps. In spite of the hunger, the misery, and the uncertainty in which they lived, Irena had fallen in love. Viktor Kende was a young man she had met in Budejovice. In the midst of the bleakness of Theresienstadt, their love had flourished. Finally they had managed to marry.

Viktor and Irena had wanted desperately to create a celebration for their wedding day. For days, they had hoarded extra food for the occasion. They had even managed to find some wine to add to the festivities. Irena had borrowed a white dress from another young woman in her barracks. Viktor had borrowed a suit that fit his tall, handsome body almost perfectly.

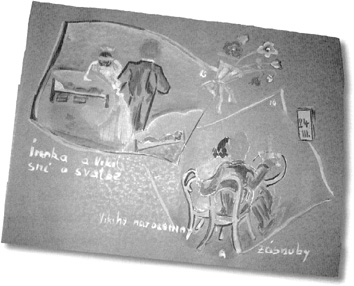

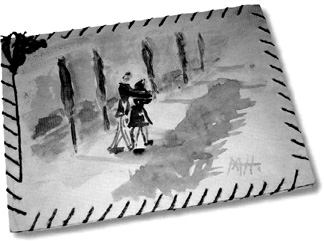

Top: A painting of Irena and Viktor’s wedding, done in Theresienstadt. Bottom: A painting of Viktor and Irena on the cover of their wedding book.

On the day of their wedding, Ruda was there to rejoice with his sister, along with his parents and a few friends and family members. Once again, their beloved Rabbi Ferda conducted the ceremony in the attic.

As the rabbi recited a blessing for the bride and groom, Irena closed her eyes and dreamed of their synagogue back home in Budejovice, with its lofty archways and beautiful stained-glass windows. Then she opened her eyes and looked up at Viktor. She reached for her new husband’s hand and held it tightly. The Nazis could not stop this couple from loving each other. She and Viktor drank wine from a small glass, and kissed each other under a wedding canopy made from blankets and old pieces of clothing.

After that, Ruda wrapped a glass in a small piece of cloth and placed it under Viktor’s foot. The breaking of a glass was an important Jewish wedding tradition, reminding everyone, even in joyous moments, that life was fragile. In Theresienstadt, with its constant reminders of the frailty of life, this tradition seemed even more poignant.

As Viktor’s foot stomped on the glass and shattered it, the guests shouted, “Mazel tov! Good fortune! May your lives be full of joy!”