By the time the war ended in 1945, more than six million Jewish people had died, many of them murdered at the hands of Adolf Hitler and his evil Nazi colleagues. Of that number, it is estimated that as many as 1.5 million were children. Most of the young people who had been underground reporters in Budejovice did not survive.

Beda Neubauer went to Auschwitz, along with his parents, sister, and brother. Following the death of his parents and brother, Beda himself died in March 1944, his frail body fatally weakened by disease.

Shortly after arriving in Theresienstadt, Rita Holzer, the girl known as Tulina, was sent to the ghetto in Warsaw with her family. She died there.

Joseph Frisch, the teacher who had maintained a school for the Jewish children in his home, died in Auschwitz, along with Rabbi Ferda and most of the other Jewish families of Budejovice.

In September 1944, Ruda Stadler received his yellow deportation slip in Theresienstadt. He left Irena and Viktor behind and boarded the train for Auschwitz. From there he was transferred to another concentration camp, where he was sent on a work detail. It was a bitterly cold day, and one of the guards at the worksite demanded the warm coat that Ruda was wearing. Ruda refused to give up his jacket. He was shot on the spot, having fought for his rights and his dignity until his last breath.

This wood carving of a strong and heroic Ruda sitting on a loaf of bread (he worked in the bakery) was done in Theresienstadt.

Irena and Viktor remained in Theresienstadt and were liberated from there at the end of the war. They were sick with typhus, a deadly disease transmitted by the lice that were rampant in the concentration camps, but they were alive.

There were others besides John who survived the war and began a new life. In July 1944, Frances Neubauer was sent to a work camp in Hamburg, where she sorted and cleaned bricks from bombed buildings, dug trenches, and built bunkers. In March 1945 she was sent from Hamburg to another concentration camp called Bergen Belsen. It was expected that she and everyone else would die there. Instead, Frances survived, and was freed on April 15, 1945. She spent the next few months in a hospital, recovering from typhus, but with proper medical attention she slowly recovered. Years later, she married a man named Lou Nassau. They moved to Australia and had two children and three grandchildren. In 1959 she and her family moved to Palm Springs, California, where she still lives today.

Frances Neubauer in present day, standing in front of the train station across from the house in which she lived before the war.

As for John, he arrived in Toronto, Canada in 1948, and over the next years he struggled to make a life for himself in this new country. He learned English, went to school, became an accountant, married, and had three children and ten grandchildren.

Sometimes, his mind would drift back to that other place – the country where he was born, the place that held those childhood memories of the swimming hole and the creation of Klepy – the place where the Nazis had taken away his freedom, imprisoned him, and killed so many of his friends and family members. It was strange to think of a place as happy and sad at the same time, but that was his memory of Budejovice – a place both joyful and tragic.

Periodically, John searched for survivors from Budejovice. He discovered that Frances Neubauer was alive, and began to correspond with her, recalling his days with Beda at the swimming hole, and the outings he had made together with other friends.

In the 1970s, John came across information that Irena Stadler was living in Prague. He wondered if she knew anything about the fate of the twenty-two issues of Klepy. Perhaps she knew whether Ruda had hidden them somewhere during the war.

He found Irena’s address and tried to get a message to her. Since the war, though, Czechoslovakia had been dominated by an oppressive communist regime, with new rules and regulations. Communism was a political movement meant to give citizens equal opportunity for work, education, social class, and economic standing. In reality, communism was harsh and intimidating. Any citizen in possession of suspicious documents could get in trouble. John did not want to jeopardize Irena’s safety, so he didn’t ask her about the newspapers.

In 1989, the communist regime was overthrown, and John was finally able to visit his old homeland. He made his way to Irena’s building, and climbed the stairs to her apartment. After ringing the doorbell with a trembling hand, he wiped the sweat from his forehead. He was sixty now, and the climb up the stairs had taken his breath away; his heart was pounding. In fact, this whole trip was physically and emotionally draining. He had not set foot in this country since March 1948. He had changed so much. Everything had changed so much.

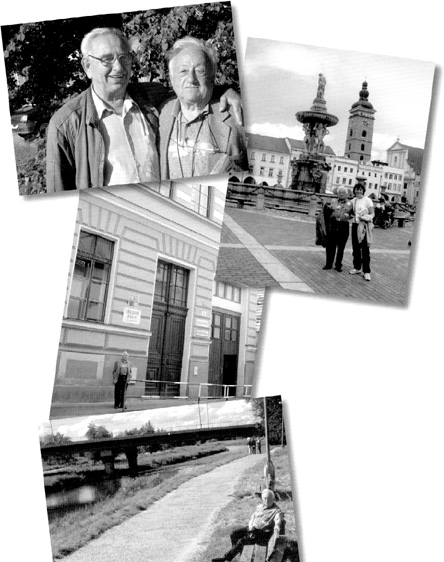

From top to bottom: John and his childhood friend, Zdenek Svec, the one Christian boy who played with John against the orders of the Nazis; John and the author, Kathy Kacer, standing in the central square of Budejovice; John standing in front of the school in Budejovice that he attended up until the third grade; John at the swimming hole today.

The door opened, and there she was – Irena Stadler, now sixty-six years old, a tall, graying woman, still strong and clear-eyed.

A photo of Ruda’s sister, Irena Stadler, taken many years after the war ended.

After they greeted each other, he could not hold back his question: “Do you really have them?”

“I do,” Irena assured him, her voice raspy, but firm.

“Can I see them? Please?” he asked, barely able to contain his impatience.

She nodded and moved down the narrow hallway. At the end of the hallway, she paused in front of a large closet. She opened the door, bent over, reached deep into the back of the cupboard, and pulled and tugged until she finally dragged out a worn brown suitcase. She carried the suitcase into the small living room, laid it on the floor, unlocked the latches of the suitcase with a loud click, and pulled the lid open.

John stepped forward to look inside. There it was.

Slowly he reached into the suitcase, pulled out the first bundle of papers, and read the title on the front cover – “Klepy #1.” Beneath this first set of papers lay twenty-one other bundles, neatly bound and perfectly preserved. The newspapers had survived.

John hugged Irena, and together they danced a crazy little dance around her living room, clutching each other. Thereza, the housekeeper with whom Ruda had left the newspapers, had kept them safe. Irena had managed to retrieve them after the war, and she had hidden them in her closet until this moment.

Now they sat down on the living-room floor and began to leaf through the pages of Klepy. John felt the weight of the stories in his hands, along with the lives of their creators. There were Ruda’s editorials, the sports columns, the poems, and the beautiful drawings by Karli Hirsch. There was a photograph of John standing with one foot kicking a soccer ball. There were the stories written by his good friend, Beda, and the jokes about Rabbi Ferda and Joseph Frisch. There were pictures of Tulina, John’s first love, and his brother, Karel, and all his other friends. It was a miracle that the newspapers had survived.

John stayed for many hours in Irena’s tiny apartment, and returned several times after that. Before leaving Prague, he photocopied the entire collection of Klepy, and took the copies home to Toronto.

Some years later, John contacted Irena’s son, Jirka, and discussed with him the best way to save Klepy for the future. They wanted other children to be able to see the newspaper and learn from its history. Eventually, Irena’s children, Jirka and Hana, decided to give the entire collection of Klepy to the Jewish Museum in Prague, Czech Republic.

It remains on display there to this day, for the whole world to see.

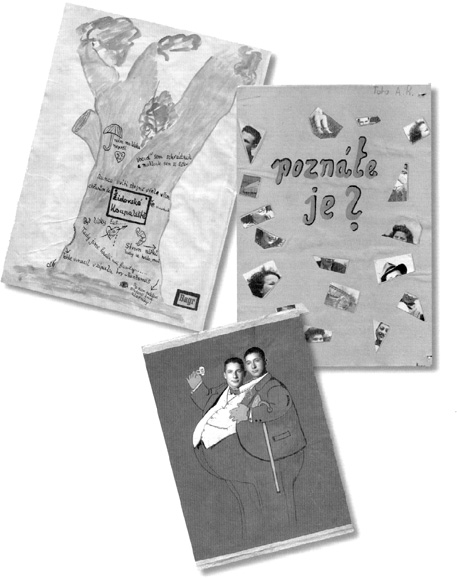

Pages from editions of Klepy, now on display at the Jewish Museum in Prague. From top to bottom: The Tree of Love; Guess Who?; Twin brothers as a two-headed man.