4

AT HOME

The family that Constantijn Huygens was to build around him would grow up to become a formidable generation, working for the Dutch Republic, the House of Orange and always for each other. In later life, his four sons and their sister were to function together with him in a network that stretched across Europe, as they travelled here and there on a variety of missions. Christiaan was the principal beneficiary of this familial arrangement, depending not only on his father’s financial support, personal contacts and diplomatic advice, but also on his brothers’ practical engagement in his work with telescopes and his sister’s ever-present concern for his welfare.

![]()

The engraved glass that Constantijn Huygens commissioned from Anna Roemers Visscher in 1621 was a gift for Dorothea van Dorp, his neighbour on the Voorhout and a close friend since they met in 1614, when he was eighteen years old and she was already in her early twenties. She seems to have taken the initiative in the relationship that developed. He wrote her poems and called her ‘Song’ and ‘Songetje’. When he went away to Leiden University in 1616 they exchanged rings, but the relationship soon faltered amid mutual mistrust. Huygens assured her of his constancy, and seemed to accuse her in a quatrain monogrammed with their interlocking initials: ‘Although the D is broken, the C is yet whole’. But his idea of faithfulness may have been more casual than hers. Their ardour cooled into an occasionally troubled friendship. Dorothea never married, while Huygens was left poetically protesting his dislike of women.

He protested too much. In July 1622 Susanna van Baerle visited the Huygenses’ house with her sisters. She was beautiful, accomplished, twenty-three years old and in possession of a fortune from her father’s Amsterdam trading business, having lost both parents by the time she was eighteen. Constantijn’s father Christiaen had it in mind that she should marry his elder son Maurits. However, Susanna refused Maurits, who soon married someone else, and Constantijn was free to try his suit. Since Susanna wrote verse and drew and painted (her subjects included birds, flowers and insects), she had far more in common with the younger man. Constantijn found that he was also able to discuss political and scientific subjects with Susanna in a way that had not been possible with Dorothea. The recently widowed Hooft courted her, too, but Constantijn eventually won her over with a barrage of verse, including a smart, satirical love poem, ‘Anatomy’, full of bodily parts and functions, not unlike Shakespeare’s sonnet, ‘My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun’:

Walk into your garden, and you will see me touch

Rubies more beautiful and sweeter than your flesh,

These cherries are they, these strawberries and currants,

There was ample time for wooing. After his return from England, Huygens waited for his next diplomatic assignment, passing the time by experimenting with verse forms and learning Spanish, the language of the enemy, which was sure to come in useful in state negotiations. In 1625 Frederik Hendrik, the youngest son of William the Silent, succeeded his half-brother as stadholder. The old stadholder’s secretary died very shortly afterwards. Huygens’s encomium – ‘Jan could read and write untiring, / Jan could reckon up the score, / Jan was loyal and never petty, / Jan was loved by high and low. / Jan had once been all in all things’ – showed that he knew what the work entailed; it was in effect his application for the job, which he got.

His modest salary of 500 guilders would be generously augmented by travel expenses and gifts for favours done in line with his duties. But he had few illusions about the reality of the work or the paradoxes that it engendered. The stadholder was by now a person of real power as well as a symbol of the state. The fact that Frederik Hendrik was also the new Prince of Orange, among sundry other titles, was an uncomfortable hangover from the time when the dynastic rule of the Habsburgs was yet to be challenged in the Low Countries. Huygens’s position was thus analogous to that of a courtier in a monarchy, yet the stadholder was the leader of a republic, and answerable to the States General. Huygens had a finely tuned understanding of the contradictions inherent in the role, and therefore in his own role too. He was not an aristocrat, but his family had been close enough to the Oranges for many years that he knew instinctively how to behave in both ‘royal’ and civic settings. He learned to read the whims and tempers of the stadholder, and to bear it when he was interrupted in his secretarial work, as he often was. Nevertheless, Frederik Hendrik was on the whole a careful, reasonable man who, like his father before him, sought compromise whenever he could. He was a soldier but also a thinker and, with Huygens at his side, would become a significant patron of the arts.

![]()

Constantijn proposed to Susanna in September 1626, and, as he recorded it in verse, her hard-as-diamond heart finally crumbled to crystal dust at the sound of his lute the following January. As a gift, she sent him a brooch set with diamonds in the form of an S. The woman he would always call Sterre – ‘Star’ – was his. She brought 80,000 guilders to the marriage; he brought relatively little except his good prospects.

Constantijn’s growing confidence in his professional position is apparent in the portrait painted of him at this time by the leading portrait painter in Amsterdam, Thomas de Keyser. Huygens appears very young, smooth-skinned, with his fine bones and pointed face accentuated by a trim goatee. His eyes are large and prominent. His hands are delicate, the right held out to receive the folded letter brought in his by his clerk, the left ungloved and resting on a table loaded with signs of learning and culture picked out in the cold, slanting light – pen and ink, a compass, a watch, globes, architectural plans and books and an extravagant lute. Huygens is smartly dressed in a black hat, white ruff and a brown matching cloak and tunic with light gold embroidering. The calfskin tops of his boots are fashionably folded down to reveal the lace trimmings of his breeches. As he sat for the picture, he happily prattled on about the impending wedding.

Susanna and Constantijn were married in Amsterdam on 6 April 1627. Later that year, they made their married home on Lange Houtstraat in The Hague. The domestic routine demanded all of the administrative skills that Susanna had built up as a merchant heiress. Well educated and self-assured, she had a powerfully logical, even mathematical mind. When they were together, she and Constantijn made important family decisions jointly. But Constantijn was often called away from home during the summer months on campaign with Frederik Hendrik’s army, and at these times Susanna’s businesslike independence was essential to the running of the home.

In their first months of married life, Constantijn had his first real experience of battle. The resumption of hostilities in the Eighty Years War following the Twelve Years Truce that lasted from 1609 to 1621 had seen reversals for the Dutch Republic, culminating in the surrender of the important garrison city of Breda in 1625, just a few weeks after Frederik Hendrik’s accession. The stadholder moved to calm religious tensions in the cities and strengthened the army. In the summer of 1627, Constantijn was with Frederik Hendrik in eastern Gelderland, where the capture of Groenlo marked an important step in breaking through the Spanish encirclement of the Republic. He found himself immersed in a strange blend of medieval and modern military technology, hearing bugle signals, drums and cannon-fire, and the clash of pikes and halberds, as well as muskets and new explosive mines set off by means of a tripwire and a sparking device. But there were longueurs during which he had time to write to Frederik Hendrik’s wife, Amalia, as she had requested, to assure her of her husband’s safety, and to exchange poems with Hooft about the progress of the campaign. He consoled himself with thoughts of home, writing love poems to Susanna and beginning to outline his major verse work based on a day in their idealized domestic existence.

![]()

Susanna and Constantijn had five children during the next ten years. Their first son was born on 10 March 1628. The godparents wanted the boy to be named Christiaen after his grandfather, but Susanna preferred to name him for her husband, and he was baptized Constantijn in the Kloosterkerk on the Voorhout.

Christiaan was born just over a year later, on 14 April 1629. The boys played together from infancy and later shared tutors. Being similar in aptitudes and interests, as well as so close in age, they formed a close bond that would lead them to work together on many occasions and to correspond frequently when they were apart.

Lodewijk, born on 13 March 1631, was the next closest in age to Christiaan. He cried the least and laughed the most of all the children, and grew healthy and bold, his father noted. He was also, ‘so somebody said, the most handsome of our children’. His more physical and less academic inclinations meant that his education would take a slightly different path from that of his brothers. Nevertheless, he too later became a useful member of the family alliance when he travelled abroad, although he was to bring shame on the Huygens name.

The fourth son, Philips, was born after another interval of two years, on 12 October 1633. During her labour, Susanna had hoped she would give birth to a daughter this time, but the pains were so great, and she had never felt herself so close to death, that she promptly stopped wishing for a daughter, lest the poor girl one day experience the same agony. Philips was the only one of his children whose birth Huygens was unable to attend, as he was away on army service; he received the news a week later, and returned home in time for the baptism. Four years later, returning once more from the field, he found the infant transformed into a healthy lad always ready to launch a surprising question or a funny remark upon anybody who happened to be in the house. Philips was the only one of Constantijn and Susanna’s children who did not live to old age; he died aged only twenty-three while abroad on an ambassadorial mission in 1657.

Susanna did finally give birth to a daughter, also called Susanna, on 13 March 1637. Constantijn remained at home for long enough to observe the infant begin to take notice and to laugh and play, and to see her grey eyes turn brown. But when summer came, he was called away once more to the field. The girl would later become an important lynchpin at home, coordinating the comings and goings of her brothers and father, ensuring that they were kept abreast of family and city news when they were away and that they always had clean laundry. She enjoyed keeping up with the fashions of the places they visited and ordering fine goods for them to send on to her. She married her cousin Philips Doublet in 1660 and long outlived her brothers, dying in 1725.

As his own father had done before him, Constantijn carefully described the birth and early life of his children. In each case, he named the godparents and the wet-nurse, and itemized the christening gifts, giving their weight when they were silver. Unsurprisingly, the most comprehensive account is given over to his first-born, Constantijn. As a new father, he lovingly described each little development, detailing month by month the trials and sicknesses of infancy, noting how it felt to handle the baby and observing each new behaviour with the curiosity of one brought before an unfamiliar wonder of nature.

But the events of the day are such that it is the birth of Christiaan, thirteen months later, that is more revealing, both in the immediacy of the account – it is the only time that Constantijn records the infant’s weight, for example – and for what it reveals of the unusual nature of the father’s life:

Christiaan our second child came into the world anno XVI.c twenty-nine on the fourteenth of April, being the Saturday before Easter, in the night, just on two o’clock, being the beginning of the aforementioned day, in the same house and Room in which Constantijn was born. From the morning of the previous day the mother began to be aware that her time was approaching, so that I, having been out at an Anatomy from 7 o’clock, was called back to the house at 9 o’clock.

Constantijn’s hunger for knowledge in art and science, especially where they might overlap, led him to the anatomy demonstrations that had begun to be held irregularly for the instruction of aspiring physicians, curiosos of all sorts and any ghoulish citizen who was prepared to pay the entrance for the show. The demonstrator on the occasion to which Huygens refers was his scholarly friend Christiaan Romph, who had performed the autopsy on Prince Maurits. Anatomy lessons typically took place in the winter – this one was late in the season – and began early in the day when it was still cold in order to minimize the stench rising from the decaying body parts. Huygens picked up his account of the day when he returned home:

Nevertheless, it appeared to pass, and at midday my wife ate with us at the Table. In the evening at around 10 o’clock the pains first truly came upon her, and from 11 she began to endure a very hard labour, certainly harder than the first, such that this child was found to be larger, measuring, on the day of baptism, 9 pounds in weight . . . He came into the world without any injury or deformity, even though my wife had feared the contrary, because she had been frightened by a poor boy passing by in the street with a gross, misshapen cheek, whose appearance was monstrous to behold.

The baptism was held on 22 April, as soon as Susanna had recovered from a postnatal fever. Two weeks later, on 3 May, Constantijn had to leave the house to join the army at ’s-Hertogenbosch, where the stadholder was preparing for a massive assault on the Spanish-held city.

Frederik Hendrik came to appreciate the true measure of his secretary at ’s-Hertogenbosch, as Huygens worked through the night to translate coded Spanish letters smuggled out of the besieged city. When the stadholder marvelled at his ability, Huygens replied that it was mere donkey work, and that he would rather spend a week turning millwheels. But he was proud of his contribution and pleased to be thus acknowledged. The success of the siege proved that it was now the Dutch who had the upper hand in the war, and it made Frederik Hendrik’s name as a military leader.

The following year, Huygens bought the estate of Zuilichem in Gelderland on the south bank of the River Waal for 41,820 guilders. With it came a coat of arms, a moated castle, lands, church goods, the local magistracy and the right to be called Lord of Zuilichem. A fine sketch of the place done many years later by the younger Constantijn shows a bend in the broad Waal with a sailing barge moored up to the dyke path that meanders close by the many-chimneyed castle. Huygens had the Zuilichem arms altered to show the outstretched branch of a tree bearing three oranges in acknowledgement of his debt to Frederik Hendrik. He acquired further lands along the riverbank in 1638 and 1642, but there were continual difficulties with rent collection and church disbursements, and frequent legal disputes, and the estate ultimately brought him little financial advantage.

As a true connoisseur, Huygens naturally chose to commemorate his elevation with more art. In addition to his wedding portrait by de Keyser, and the picture that he ordered when he discovered the miraculous talent of Jan Lievens a year later, he sat for Antoon van Dyck, when the artist paid a visit to The Hague in January 1632. This work, now lost, was perhaps a grisaille, intended to be used as the basis for a copper engraving to be included in van Dyck’s Iconography, a long-running project to produce an illustrated compendium of eminent European contemporaries that eventually included a hundred nobles, statesmen, scholars and artists. A copy engraving shows Huygens grandly robed with his hair beginning to thin across the forehead. He is facing towards us, his tired eyes apparently drawn to some object lying on a table beside the artist.

Although land may have been a safer investment than tulips or the Indies companies’ voyages, Huygens did not do well out of other property that came his way, either.* Through his marriage, he had come into possession of 150 ‘measures’ (about 70 acres) at Hatfield Chace near Doncaster in England, where King Charles I had employed the Dutch engineer Cornelis Vermuyden to drain the marshy parts of his hunting estate. Huygens later bought more acres here, but the English courts imposed heavy taxes on the improved land, and had an annoying habit of upholding the ancient rights of those who lived there. When his mother died in 1633, his inheritance included other polder land in Zeeland and Brabant, as well as the majority share of the ancestral family home in Antwerp, along with crimson wall hangings, damask sheets and family portraits. His father Christiaen had drained the land in 1617, but it had been flooded as a defensive measure when the war recommenced in 1621. Constantijn sought state compensation for the damage, but without success. Later, he was awarded another substantial estate of seventy-two houses at Zeelhem (not far from Hasselt in modern Belgium) as a favour from the stadholder, which gave him a further noble title. Perhaps his most unusual investment was in a project to build a canal to link Lake Neuchâtel and Lake Geneva as part of a bold scheme to create a route for shipping between the North Sea and the Mediterranean that would bypass enemy waters around the Iberian peninsula. Huygens’s three per cent stake purchased in 1637 only began to produce a yield thirty years later. In all, although they may not have made his fortune, these holdings were not frivolous investments, and they gave Huygens something he coveted more than wealth, which was social status.

![]()

When Constantijn returned to The Hague from Venice in August 1620, he brought back more than his formal appointment to the Dutch embassy and the gold chain that came with it. His head was filled with visions of the new classical architecture of northern Italy, and in particular the work of Andrea Palladio. In Venice itself, he would have seen Palladio’s magnificent churches. But he was drawn especially to the more innovative secular buildings. In Vicenza, the playwright in Huygens appreciated the witty drama of Palladio’s final work, the Teatro Olimpico, completed in 1585, five years after his death. He found it a ‘modern building, but truly such that there is not anything more beautiful to be seen in Europe’. Huygens carefully measured its false perspectives, ‘a wonderful thing to see, which could fool the eye of the most alert, especially by candlelight’. He sailed in a burchiello along the Brenta river, which he observed was about as wide as the canal between Delft and Rotterdam. The houses along the banks made ‘a continuous neighbourhood of the most elevated palaces and villas that one could imagine, so many that I lost the will to take notes’.

Another Palladian model was Inigo Jones’s Banqueting House in Whitehall, which opened in March 1621 during Huygens’s first visit to London as an official diplomat – a great double-cube room flooded with light from two storeys of windows.* These magnificent buildings, at once restrained and grand, perfectly proportioned in every detail yet retaining an essential simplicity, now inspired the ambitious Calvinist to build his own house in The Hague.

He needed a larger home for his growing family. More important, though, was the fact that building his own house in such a prestigious location would flaunt his skill as an architectural taste-maker and conspicuously enhance his social status. The opportunity arose when a new square, known now simply as Het Plein (‘The Square’), was laid out in the centre of the city, close to the Orange court in the Binnenhof, in 1633. Frederik Hendrik made available a long plot, 360 feet by 90 feet, along the west side of the square to Huygens, while an adjoining plot went to the Count of Nassau-Siegen, Johan Maurits, the governor-general of Dutch Brazil, a cousin of Frederik Hendrik’s.

Huygens the kenner had, of course, studied architecture, which meant that he had acquired a gentlemanly understanding of the classical orders as laid down by the Roman architect Vitruvius. However, he had neither the time nor the practical skills to manage his own project. Fortunately, though, he knew the Haarlem painter and architect Jacob van Campen, an outer member of the Muiden Circle, whom he had met at Tesselschade’s wedding in 1623 or shortly after. The resumption of the Eighty Years War had put an end to the extravagance of the early years of the century, and van Campen had found his niche when he inaugurated a version of the new classicism he had seen while travelling as an artist in Italy, tempered by an austere northern rigour. The style could hardly have been better attuned to the expressive needs of the Dutch state, and Huygens’s own house would be its first great advertisement.

The two friends worked together on the design, with Huygens closely involved in aspects of the detailing, down to the level of what cornice sections should be employed. They even talked about making Dutch translations of Vitruvius’s and Palladio’s canonical books of architecture. The job would be doubly rewarding for van Campen if it came off well, for Huygens was in a good position to feed him new commissions. As construction began, a second architect from Haarlem, Pieter Post, was engaged to implement van Campen’s intentions on site. Huygens would later praise van Campen and Post in verse, writing that they had lifted the dirty Gothic scales from the eyes of blind Dutch ‘mis-builders’, while in a letter to Rubens – in which he assured the artist that he was working to resolve the matter of a refused passport to England – he bragged of his hope that the house might do a little to revive classical architecture in the Low Countries.*

Built of brick, the main house was rectangular and symmetrical, with two narrow wings projecting forward to create a courtyard. The interiors were laid out largely by Constantijn and Susanna themselves, with separate apartments leading off to each side of the house. External details such as the capitals of the pilasters were executed in the style of Palladio’s protégé Vincenzo Scamozzi, Huygens having laboriously compiled tables comparing versions of the classical orders according to Vitruvius, Serlio, Palladio, Scamozzi and Henry Wotton. The statues on the pediment personified the Vitruvian architectural virtues of Firmitas, Utilitas and Venustas (famously parsed into English in 1624 by Wotton, Huygens’s one-time ambassadorial neighbour on the Voorhout, as ‘Commodity, Firmness and Delight’). Johan Maurits’s house, though larger overall, had no statues, and comprised a mere seven bays across the front to Huygens’s nine.

In practice, it was Susanna, now the mother of four children, who was the day-to-day client. She oversaw the works and was often on site during Constantijn’s long periods of absence. She held meetings, negotiated prices and prepared the bills. One ‘bill’, forged by the seven-year-old Constantijn in his mother’s handwriting, was presented to his father and fooled him completely. A draughtswoman and painter in her own right – better than he, in her husband’s view – Susanna also made aesthetic decisions. Huygens, meanwhile, paid regular visits to van Campen at his own country house, or received him when he was off on army campaign in a convenient part of the country. In October 1635, when plague broke out in The Hague, the whole family joined Huygens near Amersfoort, where he met again with van Campen. At home, all he could do was to complain about the workmen, who were ‘lazier than sleeping sickness and slower than syrup’, and sympathize with Susanna, who had to deal with it all.

Despite taking the economical step of ensuring that both houses made use of the same materials, progress was slow because of shortages owing to the war. For example, oak from Hesse required an import permit from the Spanish governor in Brussels, which in turn necessitated diplomatic intervention from Huygens. Bluestone for the cornices, lintels and sills was held up in transit. The builder became ill and then died. In the end, though, the cost of construction was entirely covered by the proceeds from the sale of the Huygenses’ former house on Lange Houtstraat.

During 1634, as construction began to slow, van Campen filled the time by painting a remarkable portrait of his clients. Constantijn appears in profile, sat staring straight ahead. His fine black hair is uncovered and a trim goatee tucks under his chin. Too vain to wear his customary glasses, his eye bulges and his eyelid droops. In his hand, he holds a sheet of music – a reference to marital harmony – but he is peering right over the top of it. Susanna, sitting on Constantijn’s right, and behind him from the viewer’s perspective, leans forward past her husband to look directly out from the canvas with beady dark eyes, her mouth pursed, as if issuing a challenge to the painter, her architect: is this really how you want me?

Constantijn responded archly to the painting’s unusual optics:

Blessed are the faithful rays

That light the way for man and wife

Through the joy and through the strife

Looking out in double ways:

But holier still is this conception;

Man and wife see one direction.

By the end of 1636 the house was still not ready, and Susanna was six months pregnant. The need now became urgent. The sale of the old house was agreed in February 1637, with a moving date of 1 May, a few weeks after the baby was due. At the beginning of March young Constantijn suddenly had to be taken to Utrecht for an operation on his neck. Then, on the thirteenth, the baby was born – the longed-for daughter. A little over two weeks later, Susanna was suddenly taken ill with an eruption of mouth ulcers. Her condition worsened as the deadline for moving approached, until, with three days to go, and now seeming to be in mortal danger, she was removed to be cared for in the quieter surroundings of her sister’s house. Huygens began to panic about how he would cope with the children, and how he would explain the worst when his eldest came home. He observed how the eight-year-old Christiaan would not leave his mother’s bedside. Susanna cuddled her infant girl for the last time, calling her ‘soet mockeltje’ (‘sweet chickling’), and made her will. She died quietly – ‘that beautiful death’, according to her grief-stricken husband – late in the afternoon of 10 May. The move had gone ahead as planned. The day after Susanna was buried, Huygens wrote: ‘I take possession of my new dwelling, but, alas, without my turtle-dove.’

For Huygens, the house on the Plein would always be a memorial to his beloved Susanna, and for him the best way to remember her was to maintain it as a family home for his boys and their new sister. ‘My beloved has dedicated this house to me as the last reminder of her love and as a token of herself,’ he wrote later. ‘I have taken it over, together with my own little consequence, in tears, deprived of her, my better half, for whom I shall eternally mourn like a lonely dove.’ Fifty years later, in his last will, Huygens repeated that the house was never to be sold, but was to remain within the family.

For the present, too, the house was indispensable in a political sense, because of its proximity to the centre of stadholderate power, the Binnenhof. It made a public display of the bond between the secretary and his stadholder, especially when it was pressed into service for royal entertainments, as it was, for example, in 1638 almost before the mortar had set, during a five-day ring-tilting contest arranged for the wedding of the Count of Brederode.

Its value was hardly less as a cultural symbol. One of the first important designs by van Campen and Post, Huygens’s house signalled a new turn in Dutch architecture, and before long in Dutch art, too. Between them, the two architects went on to create many of the emblematic buildings of the ‘Golden Age’. Post designed the sylvan Huis ten Bosch as a royal retreat in the woods of The Hague. Van Campen created the stadholder’s palace, Noordeinde, adopting some of the features of Huygens’s house. Later came the city hall of Amsterdam, the largest secular building in the world at the time of its completion, and ‘the single most imposing architectural venture ever undertaken in the Republic’. This vast edifice, roughly imposed on the chaotic medieval network of streets and canals, provides the clearest expression of the architect’s intention to merge the ideals of classical architecture learned from Italy with the strictures of Calvinism to create an authentic Dutch baroque style. For all its carved swags of fruit, the building remains cold and forbidding, an effect achieved by two tiers of severe pilasters running around its full perimeter like a rank of sentries.

All this makes a heavy load for one house to bear. Perhaps it is not surprising that Huygens later commissioned a second house, different in almost every significant respect from the one on the Plein, where he spent the greater amount of his time in later years, finding poetic inspiration and respite from city life.

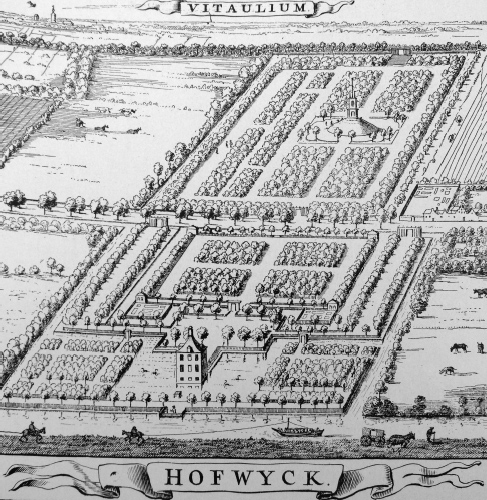

![]()

It was a pun, of course. Hofwijck: hof being ‘the court’ or merely a court or garden; wijk being an area, a quarter or a district, also a walk or one’s regular round or beat, as well as a retreat or even a flight from somewhere else. So, Hofwijck was his ‘courtly quarter’, or ‘garden circuit’, or equally his ‘escape from the court’. Except that he was far from withdrawn from the life of the court. The name was a self-mocking jest from a poet who loved to play with words.

He bought the land near the ‘pretty village, or, rather, little town’ of Voorburg on the bank of the Vliet, the old canal linking the major cities of Holland, in December 1639. To the south, across the Vliet, lay water meadows. (Much of the area bounded by the cities of Delft, Leiden, Gouda and Rotterdam was once a large freshwater lake, the Zoetermeer, which was gradually turned into polder land during Huygens’s lifetime.) In other directions, Huygens could see the walls of Delft, many windmills and the church tower in The Hague. He was a ‘weathercock’ uncertain where to turn for the best view.

Huygens swiftly acquired adjoining slivers of land that enabled him to expand the estate, and directed the planting of trees to furnish his arcadia. Building work began the following year and the house was ready by late 1641. His architects were those who had worked for him in the city, the house conceived by the ‘reason-rich mind’ of van Campen, and ‘midwifed’ into the world by the pen of Post, as Huygens put it. Once again, Huygens himself played a major part in the conception of the overall design. As on the Plein, axial symmetry was a guiding principle, but the mathematics of this ideal villa were purer, a simple brick cube apparently afloat on a square lake. There was no place for ‘crooked corners’ or ‘imparity’ in a house modelled after God’s perfect creation, man. Doubled windows made eyes, ears and nostrils in the facade.

It was a true retreat in the sense that it was too small to entertain staying visitors or to live at all grandly. The entrance opened directly into the main room, which was often used for musical gatherings. A small library space led off to one side. Downstairs lay a kitchen where the family usually ate without formality. Upstairs were a couple of small bedrooms, and above that an attic space that Christiaan would later adopt for his scientific work. Just as he had helped to introduce a new Dutch baroque style for city architecture, Huygens was setting a trend in the countryside, too. Few wealthy Dutch citizens possessed a country seat in the 1630s, but within a generation nearly half of them did, and by the end of the seventeenth century four out of five of these ‘pseudo-aristocrats’ owned new estates. The Vliet in particular was soon lined with grand villas, transforming it into a northern equivalent of the Brenta that Huygens had admired on his visit to Venice.

The Vliet had become part of a growing public transport or trekvaart network in 1636; a spur was added into The Hague in 1638, just before Huygens made his purchase. By the mid seventeenth century, there was a more or less hourly barge service linking Rotterdam, Delft, The Hague, Leiden, Haarlem and Amsterdam, and by 1665 there were 400 miles of inter-city canals. The barges were pulled by men at first, and later by horses. When the canals froze, the towpaths still provided convenient connections by foot. Huygens erected a landing stage at Hofwijck from which it took forty minutes to reach The Hague. On his journeys, he enjoyed the banter of the skippers, listening for dialect terms which he might use to enliven the dialogue in his plays.

It was in the poet’s paradise garden where he was able to demonstrate most fully the Vitruvian axiom that ideal planning should take the human body as its template, an idea perhaps inspired by the elongated proportions of the site. The house, with its window eyes, was the head; the bridge across the moat, the neck. From there, arms branched off down each side of the garden. In the middle was the ‘stomach’, an orchard where the family planted apple and cherry trees and grew melons. The waist was made by a public right of way, the Westeinde road, that cut across the land Huygens had bought. Beyond this, the Vitruvian man’s legs stretched out along paths and water-filled ditches, the latter suggesting to the scientifically minded Huygens the newly discovered circulation of the blood and the regulation of body (and house) temperature. The entire estate was a compact 35 rods at its widest and 110 rods in length (125 × 410 metres).*

Trees were planted according to a detailed plan such that each one would play a role in the whole composition. From Frederik Hendrik, Huygens received a present of tall pines and other conifers. Birches stood around ‘like tapers in church’, but oaks suffered in the sandy soil. The plot was long enough that the many varieties of tree would at first obscure any view of the house. The walk out from the house and through these woods thus made a transition from the material world to one more spiritual, ‘a tame wilderness from savage civilities’, as Huygens put it in one of his characteristic antitheses. Concerned about the cost and disruption of removing the soil dug out to create the ditches, Huygens even had the thought to build a central mound of surplus earth in the middle of the garden. From the summit, it would be possible to see The Hague, ‘the white wall of dunes at Scheveningen’, and the sea beyond. He crowned the hillock with a small lighthouse. ‘The key to my heart,’ Huygens wrote, ‘is the one to this garden.’

Huygens’s new retreat inspired his longest and perhaps most charming poem, which he finished in December 1651. In 2,824 densely packed lines of alexandrine verse, he presented his vision of Hofwijck as a place of miraculous organic fulfilment, like an overnight ‘mushroom revealed in the light’. Hofwijck is in effect an early example of the country-house poem, a genre of works that began to be produced by many poets in appreciation of a visit to the estate of a wealthy friend or patron. These poems typically blended admiration for the house and the good taste of its owner with praise for the rustic way of life and the civilized pursuits made possible in the country, from arboriculture to stargazing.*

Because Huygens was both the poet and the lord of the manor, he was able to offer rather more. He unfolded not only the house and its garden but also much of his philosophy of life. He confirmed Hofwijck’s importance as a refuge, with a list of things banned, which began: ‘I ban the whole of The Hague / With all its backbiting. I ban the filthy plague . . .’. With the Vliet barges passing by and the road cutting through the estate, it was nevertheless a populated refuge, and he gladly pictured his splendid surroundings as part of a community. It was his conceit that his lofty trees would shield the townsfolk of Voorburg from harsh winds. But above all, Hofwijck was a place for Huygens to discourse with friends or to contemplate the world alone outdoors while sitting upon its grassy banks, or to be indoors with his musical instruments and books – he feared for the strain the latter would place on the timbers of the house. He imagined guiding his reader round the place in a future time ‘as if our yesterday were an age ago’, when his grandchildren might be living there. His cherished saplings he visualized now in their maturity as an inheritance that these descendants too should nurture. He realized without false modesty that Hofwijck the poem might outlast Hofwijck the house:

Hofwijck as it is, I would have the stranger see,

Hofwijck as it will be, the Hollander must read.

So feeble is man’s work, it lasts less than paper.

Meanwhile, the reflections in the still water seemed to double his riches in an illusion of ‘opulent alchemy, or I never knew any’. In winter, the lawns flooded, the waters froze, and out came the skaters, carving patterns in the ice. In summer, nightingales nested in the garden, reminding him of the sweet-voiced woman – one of his musical companions, Utricia Ogle – who once sang there.

Yet this whole idyll was presented with an aching sense of loss. This is the effect of Huygens’s imagined standpoint in the distant future, which serves to display his proper humility as well as his satisfaction in his creation. He even foresaw Hofwijck left upturned in ruins following some divine cataclysm, with the memory of his happy marriage lying among the fallen stones:

. . . the lowest thrust up high,

The highest brought to ground: the name-plate far off seen,

Lay sadly toppled down, SUSANN and CONSTANTIN:

But never sundered yet, as e’er they must remain,

Their souls, I now do mean, as were their bodies twain.

In fact, he enjoyed many summers at Hofwijck, especially during the Stadholderless Period beginning in 1650, when his diplomatic duties became lighter, before it passed to his children and eventually became Christiaan’s less happy home.