6

REVERSALS AND COLLISIONS

News spread slowly that Descartes had died of pneumonia during his first winter in Stockholm. In April 1650, two months after the event, Christiaan Huygens passed on to his brother Constantijn that he had seen it reported in the Antwerp gazette ‘That in Sweden a madman had died who said that he could live as long as he wanted’. Christiaan added: ‘Note that this is M. des Cartes.’ Constantijn found this ‘quite funny’.

The philosopher’s death moved Christiaan to write a short verse epitaph, the only time he showed any sign of following his father’s literary path. The last of its four stanzas runs:

Nature, take to mourning, come foremost to lament

The great Descartes, and demonstrate your woe;

When he let go the day, you were lost to light,

It is only by that torch we could imagine you.

Earlier that winter, the same harsh weather had forced Christiaan to abort his plan to travel on from Denmark in order to see his idol in Sweden. His elder brother, meanwhile, was enjoying his own travels, proceeding ‘galliardement’ through Switzerland and Italy, where he enjoyed ices ‘powerfully flavoured with cherry, strawberry, lemon, amber, cinnamon &c’, which he discovered were made in little bottles placed in snow mixed with salt and saltpetre. He marvelled at the ‘great peaks of the Alps, which I can see from my room, terrible to behold’, and complained that Christiaan in return was telling him nothing of what he was seeing on his trip. He hoped that he, too, was keeping a journal so that they could read them together when they returned home. In fact, Christiaan was holding little back. He replied sourly of his scenery: ‘the greatest I have seen [in Denmark] is less like the Alps and more like the mountain of Voorburg which my father has had made [in the garden at Hofwijck].’

Later that year, on 6 November, came a more shocking death, and one that was to have a severe impact on the Huygens family. The stadholder, Prince William II of Orange, succumbed to smallpox at the age of twenty-four, after just three years in the post. Eight days later, his wife Mary Henrietta Stuart gave birth to a son, William III of Orange, who would eventually succeed him as stadholder and become king of England, Scotland and Ireland.

During his brief and tempestuous reign, William II had been more bullish in pushing back the Spanish than his predecessor, Frederik Hendrik, and had aggressively promoted the Protestant Reformation in areas formerly controlled by Spain. But his progress came at some cost to internal unity in the Republic as squabbles arose over the sovereignty rights of individual provinces. On 30 July, in an attempt to impose overall control, William had staged a coup designed to bring Holland (the most powerful province, with its capital in Amsterdam) into line with the other provinces, and to define a peacetime role for the House of Orange. This bold action appeared to resolve the sovereignty issue, and, by agreeing that the titular figure of the stadholder was not a monarchical rank, and was therefore not incompatible with the existence of the republic, William promised a new political order. His untimely death immediately undid much of this work, and the United Provinces entered a long period of stadholderless government. In The Hague, there was such heavy snowfall that William’s funeral service had to be postponed because the mourners were unable to reach the city. The meltwater that spring combined with storm surges to produce Holland’s worst flooding in eighty years. These were omens that the Dutch knew too well how to read.

For Constantijn, three decades of service as a secretary to various stadholders was at an end, and with it his influence over statecraft. However, he retained his involvement with the House of Orange, continuing to serve Frederik Hendrik’s demanding widow Amalia, not least in the creation of a magnificent memorial to her husband at the Huis ten Bosch palace in The Hague. This was a great hall of paintings by the best Dutch and Flemish artists, commissioned to commemorate the victories he had gained for the Dutch Republic.

The sudden reversal in the Huygens family fortunes put paid to any lingering expectation that Christiaan might follow in his father’s (and his grandfather’s) footsteps by joining the secretariat of an Orange stadholder, and he gratefully seized the opportunity to give himself completely to mathematics and physics. From now on, although he would typically be pursuing a variety of investigations at the same time, all would have their basis in a fundamental wish to learn more about the physical world. Christiaan Huygens was beginning to mould himself in the image of a creature that did not yet exist, the professional scientist. The projects he took on at first were both practical and theoretical in nature, and included improving the design of his telescopes, a consideration of the nature of fluids, and problems more easily described than solved, such as how solid shapes float on water.* An extended analysis of the geometry of curves included a new method of calculating the length of given sections of the circumference of an ellipse. When applied to a bisected circle (a special case of an ellipse), this yielded a new value, accurate to nine decimal places, for the mathematical constant π, which had not been improved since Archimedes. The work greatly pleased his former teacher van Schooten, with whom Christiaan corresponded frequently at this time, and it made his name in mathematics.

Christiaan’s achievement vindicated Marin Mersenne’s early championing of his friend Constantijn Huygens’s young ‘Archimedes’. Before he died, Mersenne had done much to spread the young Dutchman’s name in Paris and beyond, making France’s greatest mathematical minds, Pascal and Pierre de Fermat, aware of his talent. When Lodewijk Huygens travelled to London in December 1651, he discovered that the philosopher and would-be mathematician Thomas Hobbes, too, knew all about his brother’s abilities from Mersenne, and indeed claimed to have been perusing his quadrature of the parabola and hyperbola only a few days before. ‘He praised it abundantly and said that in all probability he would be among the greatest mathematicians of the century if he continued in this field,’ Lodewijk reported.

![]()

Huygens began to make even greater progress in the field of mechanics as he noticed flaws in Descartes’s laws of motion. He first raised his concerns with Gérard van Gutschoven, the professor of mathematics at Leuven University and a former associate of Descartes, in January 1652. Descartes had enumerated laws governing collisions between bodies of various masses moving at various speeds. These included the statement that a smaller moving body colliding with a larger stationary body would not cause the stationary body to move, but would only rebound itself. This was clearly wrong, as a moment’s play with two pebbles would have shown him. But Descartes was not a man given to experimentation, and he may have felt that, since he was discussing ideal bodies rather than anything that existed in nature, such demonstrations would have no bearing.

Despite his Cartesian indoctrination, Huygens was always mindful of the physical world. His re-examination of the Frenchman’s theory of collisions led him to the realization that it was not one body or the other, but the centre of gravity of the whole system – in this example, the two unequal bodies taken together – that was significant. This centre has the same velocity and direction after the impact as before, or as Huygens put it, the ‘quantity of movement’ is conserved. This new theory of collisions, in which he reluctantly overturned Descartes’s idea, came close to describing a concept of force that was only fully worked out by Newton in the following decade.

Van Schooten, however, was not keen on where his protégé’s train of thought was leading him. He insisted that Descartes must be right, and may have persuaded Huygens not to publish his analysis for that reason. The work only appeared in a paper in the French Journal des Sçavans in 1669, a few years after Newton’s laws of motion, and then in a longer treatise, De Motu Corporum ex Percussione, which was not published until after Huygens’s death.

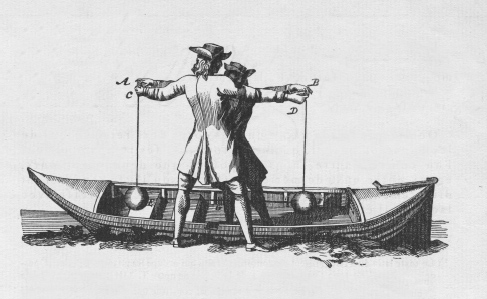

An engraving made for De Motu shows two men, one standing in a passing barge, the other closely facing him standing on the water’s bank. Perhaps the idea came to Huygens from watching the ferrymen plying the Vliet waterway that runs past the garden at Hofwijck. In his outstretched arms, the man on the bank is holding two identical balls suspended on strings. The man in the barge has his arms outstretched, too, so we can imagine that the strings with their equal weights might shortly be passed to him.

Setting the balls swinging like pendulums, the man on the bank finds that they exchange their velocities when they collide; in other words, the one in his right hand that was swinging to the left until the impact now moves to the right, and vice versa, and the speed of their separation is the same as the speed of their original approach. When the man on the moving barge follows this action, the situation appears to him exactly the same. However, the man observing him from the bank now sees the two initially unequal relative velocities of the balls exchanged after collision because of the additional component of velocity due to the passage of the barge. Proceeding in Archimedean fashion by using geometric propositions rather than the algebra we would expect to see today, Huygens was able to extend his analysis of this problem to include bodies of unequal mass, leading him to a more complete theory of collisions that admitted the concept of relative motion. Huygens believed that the visual image of the two men and the moving barge would convince even the greatest sceptic of the rightness of this principle of relativity.*

Further consideration of the mechanics of these reversible collisions in 1652 led Huygens to the discovery that the total kinetic energy of the system is conserved. He stated this proposition as follows: ‘In the case of two bodies which meet, the quantity obtained by taking the sum of their masses multiplied by the squares of their velocities will be found to be equal before and after the collision.’ This time he did find it more profitable to proceed using algebra, and his expression of this rule in algebraic symbols marks the first time that a mathematical formula was used to describe a relationship in physics.

Aristotle had denoted simple quantities such as lengths by the use of letters in geometric problems. Galileo was the first to fully understand that mathematics could be used to describe certain laws of nature, although he used ratios and sequences of numbers to do this rather than algebraic relationships. But Huygens appears to have been the first to designate a function, in this case velocity or speed, which is a function of time, using a single symbol, and to manipulate it with other quantities in mathematical equations. In his nomenclature, a and b represent the two masses seen in the engraving of the men and the barge, and their respective velocities are denoted x and y. The equations for their kinetic energies before and after collision then take the form axx + byy and so on. These equations occur in his notes, but Huygens did not persist with the use of algebra in the final text of De Motu, or on other occasions when it might have proved helpful, such as describing the properties of the pendulum. He remained loyal to the geometric methods of the classical mathematicians, even after the calculus of Leibniz and Newton had shown a more powerful way forward, and in this respect truly lived up to the nickname given him by his father and Mersenne: the ‘Dutch Archimedes’.

We are accustomed to the idea that many of the laws of science are best – which is to say, most concisely and powerfully, and least ambiguously – expressed in mathematical formulae. The symbolic representation and manipulation of real physical quantities is now regarded as an essential tool of science. But in the seventeenth century it was still usual to try to explain the physical world using lines and angles to represent variable quantities. This was no primitive method, however. ‘It requires ingenuity to draw the correct triangles, to notice about the areas, and to figure out how to do this,’ according to the twentieth-century physicist Richard Feynman, in a discussion of the respective merits of geometry and algebra in his book The Character of Physical Law. The reward was a visual and quantitative representation of events such as the acceleration of an object falling under gravity that before could be observed and described only in qualitative terms. Geometry used in this way is an attempt to show rather than tell, which mathematical formulae cannot hope to emulate. For Huygens, it surely also fell within a Dutch tradition that included surveyors such as Stevin and Snel, cartographers such as Gerard Mercator and Willem Blaeu, and the many painters demonstrating their mastery of perspective, all reliant upon the geometry of triangles, and inspired by the land lying like a sheet of paper before them.

![]()

Later in 1652, Christiaan Huygens began to think about lenses. Like Descartes, his approach to the topic was theoretical and mathematical at first. Descartes had tried to show that elliptical or hyperbolic lenses would not suffer from spherical aberration – the tendency of a spherical lens to produce a focused image only through the central part, while rays of light passing through the edges of the lens converge at other focal lengths. The problem, as Christiaan’s father had found from his unsuccessful exercises working with lens-grinders, was that lenses of this form were very hard to make. However, Christiaan believed that optical images might be made free of aberration if a second spherically ground lens were to be placed in the path of the light. As with Descartes’s hyperbolas, though, his mathematical demonstration of this possibility could not be converted into practical devices. But the defeat did awaken Huygens’s interest in the theory of refraction.

In his workshop in the attic of the family house, he now measured the refractive index of various glasses and waters as accurately as he could. Although it was the practicalities of telescope design that most concerned him, he treated the optical property of refraction with a high degree of mathematical rigour, aiming to provide a solid theory of optics for the instrument, which had now been in widespread use without one for nearly half a century. In a series of geometric propositions and demonstrations making use of the sine law of refraction, he analysed the propagation and refraction of light through increasingly complex lenses. Geometry was a persuasive tool here, revealing at a glance the index of refraction in the respective lengths of lines representing the incident and refracted rays of light. Huygens’s mathematical analysis even extended to an examination of the rainbow, which yielded angles of refraction, but no clue to the origin of its colours. The work was valuable nevertheless. Huygens’s geometrical figures were often also optical diagrams, accurately representing the path of light at a time when it was still not known that light possessed a direction of travel, and most drawings of optical instruments were notably vague about what happened as it passed through the mysterious space between their lenses.

Like so much of Huygens’s work, however, this ‘theory of the telescope’ was not published in his lifetime, despite van Schooten’s support this time. If he had published, it would have ensured his priority in explaining some aspects of refraction over later works on optics by the English mathematician Isaac Barrow as well as by Newton. Huygens continued to make new optical discoveries, which were eventually compiled in his major treatise on light (Traité de la Lumière, 1690) and in a posthumous work dedicated to the topic of refraction. These early forays into mathematical optics were perhaps most important to him as mental preparation as he set about making his own lenses for the first time. The lucky invention of the telescope had embarrassed natural philosophers into developing a theory of optics; now theory stood ready to inform practice.

![]()

One of the best descriptions of how to grind lenses comes from the journal kept by the Middelburg Latin teacher and natural philosopher Isaac Beeckman. Towards the end of his life, still only in his forties, in ill health and often appearing morose and dishevelled, Beeckman turned to grinding his own lenses, having failed to find a supplier of ready-made telescopes to his liking. His diary for the year 1634 draws on all that he was able to read about the subject and glean directly from the best lens-grinders in Middelburg and beyond, and records his struggle to equal them in their art in such detail that it came to serve as an instruction manual for others.

Having studied the literature, Beeckman bought a grinding basin and the other necessary equipment, and took some preliminary lessons from Johannes Sachariassen, the man who had claimed that his father had invented the telescope. Although Sachariassen was happy to use ‘collet’ – recycled glass – as his raw material, Beeckman soon came to prefer cristallo or ‘Venice crystal’, glass of very high optical clarity, which was available from Middelburg’s superior glassworks. Rock crystal, or pure silica, which is even more transparent, he disliked, however, because of its highly reflective surfaces. First, the basic form of the lens is cut from a plane sheet of glass using hot pincers. Then the shaping begins. For a convex lens, the grinder uses a basin of cast iron or other metal with a very slightly greater radius of curvature than the desired lens. For a concave lens, a rounded stone is employed, either held and used freehand, or suspended on a rope to scribe a constant radius.

The flat piece of glass is ground into shape by means of ever finer abrasives. The grinder starts with coarse sand, which is moistened to make a paste. He then repeats the procedure several times using finer sands, prepared, as Beeckman describes it, by sifting through successively finer weaves of cloth and then washing in rainwater. The finest sand must be moistened with distilled rainwater so that the abrasive medium remains free of organic contamination as well as larger grains. Grooves scored into the grinding basin help to retain the sand in position. Sometimes a layer of leather or cloth is introduced between the glass and the basin, too, in order to even out the pressure that is applied.

Much is left to the skill and care of the lens-grinder. Each stage takes longer than the last, as the finer new compound must erase the scratches left in the glass by the coarser medium used in the previous stage. It requires close attention to avoid pits and wells forming in the glass, and concentration to ‘hold the centre’ of the future lens. ‘One must grind lightly for sufficiently long, otherwise one begins to press before the sand is greatly broken up, which makes scratches,’ Beeckman wrote. In his diary entries, he compared the methods not only of professional lens-grinders but also of artisans in other fields, searching widely for possible improvements in technique. He observed, for example, that oil is not suitable for mixing with the sand, noting that painters grind their pigments with water first before mixing them with oil for application to the canvas.

Even a careless final wipe of the glass could be enough to undo hours of effort if a single outsize grain of abrasive remained. There were other precautions to be observed, too. For instance, an English lens-grinder in Amsterdam whom he visited for further instruction warned Beeckman that he should take care his hands were not greasy, because that might damage the leather he was using.

Beeckman laboured diligently through the spring and summer at the task he had set himself, but occasionally his frustration got the better of him, and he felt he was getting nowhere:

Up until this 25th of July, I have polished no glass on the basin except by accident, and can do it no longer. It is possible that I am wiping off the glass too heavily, and that there remains always some dust hanging to it. Going at it too carelessly: stuff sticks to the cloths, on my hands, arms, etc., which I set down here and there as I wash the glass, not shaking it off well enough, not washing my hands, touching my dusty clothes with my arms etc.

But his persistence had its reward in the end. In the spring of 1635 an impromptu contest was held at a friend’s house in Middelburg, where Beeckman’s lenses were compared and found to be superior to those of Sachariassen. So far as is known, however, Beeckman never went on to make a working telescope, and he died two years later, leaving his work unpublished.

![]()

In November 1652, having likewise failed to find good enough telescopes for sale, Christiaan Huygens set to work much in the same way as Beeckman, proceeding by trial and error and seeking advice on best practice. He wrote to Gutschoven asking what mould shapes he should use, how fine to sift his sand, and what sort of glue to use (a strong adhesive was needed to temporarily bond the glass to a handheld wooden form). Gutschoven responded helpfully, and reminded Huygens of the importance of maintaining the axis of symmetry while the glass was being ground so that the lens would have a central focus.

Huygens copied many of Beeckman’s techniques, but also made some decisions for himself. He found, for example, that very clear white glass had a tendency to ‘sweat’, or lose its high lustre, and so he preferred other glasses even though they might have a slight colour. Huygens’s surviving early lenses have noticeable tints of grey and green, but are remarkably free of bubbles and other defects. He also experimented with counterweights and a lathe to turn the basin against which the glass was ground. These were labour-saving innovations, although it is probable that an element of Cartesian idealism was also present in his enthusiasm for automation.* As he learned more, Huygens also made notes – keep the sand wet to prolong its life in the grinding basin, but not too wet or else the glass was liable to jolt, and so on. Stopping for an occasional rest was feasible, but while working, intense manual concentration and fine motor control were essential. He reminded himself: ‘Always think about keeping an equal pressure. Often paused and brought the hand to bear again with an equal pressure. It is preferable to be alone.’

In fact, Christiaan often worked with his brother Constantijn when grinding lenses, and found joy in their collaboration. The addition of the manual lathe demanded the presence of a second person to provide the motive power. But there was clearly also something highly congenial about sharing such a demanding and monotonous job with familial company. Late in life, when he was back in The Hague after his glorious career in Paris, and Constantijn was away accompanying William III on the invasion of England in 1688, he pined for these placid times.

Although it has obvious visual possibilities, and although the trade was reasonably widespread, the lens-grinder at his table never became a popular subject among Dutch painters. It has the same sense of quiet creative purpose as letter-writers and music-makers, and even comes ready with a fitting moral theme of honest labour directed towards achieving greater clarity of (spiritual) vision. But it was perhaps too specialized an activity to make a saleable picture.

Which of the brothers cranked the handle that drove the rotating platform? And which held the glass to be ground? It is likely that they took turns, if only to alleviate the tedium of the work, although there is reason to think that it was the more artistic Constantijn who was better at the skilled task of offering up the glass. Even with the lathe rumbling away, it was a contemplative business. The grinding compounds are so fine that little sound arises from the abrasion. There is no fire or smoke and little smell. Only the gentle wooden rhythm of the pulleys was there to break the silence, unless one of them spoke. The continuous labour could be interrupted from time to time in order to wash off or add more compound. But apart from that, there was a kind of meditative frugality about the task.* Because of the dust, it was best not to wear good clothes. Very modest quantities of the abrasive materials were all that was required, and the best results were obtained with very little – but even! – pressure applied by the operator, whose main actions otherwise were to make slight adjustments in the lateral and rotational position of the glass on its form with respect to the basin platform underneath. The room in which the work was done had to be scrupulously arranged and kept clean to minimize the risk of cross-contamination of the fine compounds by grains of the coarser ones used in the early stages of the process. In short, lens-grinding might almost have been designed as an activity with little other purpose than to satisfy Calvinist piety.

![]()

The Stadholderless Period, as the years from 1650 to 1672 are known in Dutch history, began inauspiciously, with much jostling for influence among the provinces and between the nobility and military, loyal to the House of Orange, and the civic interests of the merchants and traders who generated the country’s considerable wealth. Any mood of republican idealism was soon shattered by the reality of riots in the cities and the rise of fresh tensions abroad.

In October 1651, the English Parliament passed the Navigation Act in an effort to protect its seafarers’ commercial interests against the more efficient Dutch maritime trade. Growing harassment of Dutch ships at sea precipitated the first of three Anglo-Dutch wars the following year. At the same time, Johan de Witt amassed support at home by promising the provinces greater sovereignty in a federated republic, and at the age of twenty-seven was duly confirmed in office as Grand Pensionary of Holland. Victory at sea swiftly followed.

The difficult relations between England and the Dutch Republic at this time – allies in their antimonarchical aspirations, but rivals in trade and international expansion – are entertainingly glossed by Andrew Marvell in his satirical poem ‘The Character of Holland’. Marvell was well acquainted with the Dutch, had learned to speak the language and may even have visited the Huygenses in The Hague when he travelled to the country as a young man on a five-year tour of Europe during the English Civil War in the 1640s. His poem is riven with contradictions as he struggles to turn his former admiration for the Dutch Republic to the purposes of propaganda.

He begins by disparaging the country ‘as but the off-scouring of the British sand; . . . This indigested vomit of the Sea / Fell to the Dutch by just propriety.’ It is not just the low-lying terrain that is found wanting, in Marvell’s opinion, but the polyglot population that has had the temerity to raise ‘their watery Babel’ upon it. He is discomfited, too, by the religious pluralism of the place, and especially its relative tolerance of Roman Catholic worship alongside Protestantism – ‘Faith, that never could Twins conceive before, / Never so fertile, spawned upon this shore:’ – and by the fact that the constant threat of flooding has engendered a spirit of cooperation that has led in turn to the emergence of a true republic, a condition that England was at that moment seeking to emulate. In a reference to The Hague, which did not gain city status until 1806, he adds: ‘Nor can civility there want for tillage, / Where wisely for their court they chose a village.’

Marvell’s verse served its patriotic purpose – and its author – well, and would be reissued twice during the subsequent Anglo-Dutch wars of the 1660s and 1670s. Meanwhile, the English poet’s love–hate relationship with Holland was answered in the play that Dutch writers often made of the words Engelsen and engelen, characterizing their English former allies as fallen angels. A few polemics were less ambivalent. Vondel, for example, likened London to a ‘new Carthage’, implying Holland was the civilized Rome.

![]()

These were testing times for all the Huygenses, who had to strike a fine balance between old loyalties and the new regime, especially when tensions flared between the Orangists and de Witt’s republican government as the war looked like being lost. It must have helped to ensure smooth relations that Christiaan at least was able to maintain personal contact with de Witt because of their shared passion for mathematics. Christiaan thought it advantageous to dedicate his first major treatise on clocks – with its promise of advances to come in marine chronometry and greater glory for the Dutch at sea – to de Witt in 1658, and de Witt, for his part, the following year asked Huygens to read his treatise on the geometry of curves for errors and suggestions.

Christiaan’s brother Lodewijk, meanwhile, had been the most closely involved in international politicking. His youthful encounter with Hobbes had come when his father secured him a place as an aide on a special embassy to London led by the poet and former Holland Grand Pensionary Jacob Cats in an ill-fated effort to avert the war. On 12 February 1652, Lodewijk wrote in his journal that he had paid a visit

to the renowned philosopher Hobbius who, upon having been exiled from France for the strange notions in the book which he entitled Leviathan, has come back to live here again. He is a man of rather over than under sixty years of age and sickly most of the time. He was still dressed in the French manner, however, in trousers with points and boots with white buttons and fashionable tops, wearing besides a long dressing-gown.

They talked happily for more than an hour, Hobbes speaking only English, with Lodewijk interjecting in Latin. Doubtless they discussed the state of their respective nations, but they ranged, too, over the physics of motion and gravity, with Hobbes full of admiration for Christiaan’s mathematics.

Although the diplomatic effort ended in failure, the trip may have been a personal success for the twenty-year-old Lodewijk, whose father had hoped that it would shock him out of his immaturity and give him a chance to learn English. As a member of a prominent Orangist family who could be presumed to have royalist sympathies, Lodewijk was in a potentially awkward position in Oliver Cromwell’s England. He would have had to take care who he spoke to and think carefully about what he said – lessons he was in greater need of than his more thoughtful and responsible brothers.

![]()

And the father? How was he to pass the time now that there was no stadholder to serve? There was poetry, of course. He completed his great verse of retreat, Hofwijck, at this time, and, assisted by Christiaan, began to organize the contents of a major edition of his poems under the title Koren-bloemen (‘Cornflowers’). This was to be the first collection to be published by any poet in Dutch, and it eventually (an enlarged edition was published in 1672) included Hofwijck, his other long verses, Dagh-werck and Zee-straet (concerning his proposal for a grand avenue stretching from The Hague to the sea at Scheveningen, which was later built). Also featured was Trijntje Cornelis, ‘one of the most uproarious farces of the seventeenth century’, about the misadventures of a Holland bargeman’s wife when she finds herself in the alien world of Catholic Antwerp. The play was notable for its use of local dialect to comic effect, and was definitely not the sort of thing approved of by the dourer sort of Calvinist.* Bringing the work to more than 1,300 pages were several thousand sneldichten – epigrammatic ‘quick poems’ of four lines or so in a variety of languages.

Although it was his eldest son, named after him, who most closely followed his professional path, it was always Christiaan whose company Constantijn longed for the most. Christiaan was clearly literary enough to be useful in preparing his father’s verses for publication, and they enjoyed making music together and could discuss painting and the arts. They were also able to converse on scientific matters, especially optics, which began to revive in Constantijn’s interest as he found himself with time on his hands. However, father and son necessarily had different conceptions of what science (then still called natural philosophy) actually was. Their generations fall conveniently either side of the beginning of what is sometimes called the Scientific Revolution, and so it is worth dwelling briefly on the two men’s contrasting approaches. For Christiaan, as we have seen, science already had the status of a vocation or profession, to be undertaken with rigour and dedication, even if he did pursue many topics at once. Constantijn, on the other hand, remained ‘a dilettante in the best sense of the word’. He had a highly developed curiosity about the physical world, and some sense of which fields it might be rewarding to explore (optics and medicine interested him, but he was properly sceptical about alchemy and astrology). But for the most part he lacked the tools – experimental design, painstaking observation, accurate measurement, mathematical analysis – to answer his own questions, as is revealed in a remarkable episode involving one of the greatest intellectual women of the age.

![]()

One of the longer poems that Constantijn Huygens included in Koren-bloemen is called Ooghentroost, and is addressed to a family friend who had lost the sight of one eye owing to cataracts. The word is translated literally as ‘eyes’ comfort’, but it is also the Dutch name for the plant eyebright or euphrasia, traditionally favoured by herbalists for the relief of eye irritations. This was not the only occasion on which Huygens used this title, and his choice reflects his ever-present preoccupation with his own and others’ eyesight. In his case, it was probably a thyroid condition called exophthalmus, which causes tissue to build up behind the eyeballs, that left him with his ‘wide-open, large and bulging eyes’, and necessitated his wearing spectacles from boyhood. Perhaps it also sparked his interest in optics.

Huygens puts his own poor eyesight on a par with that of his more seriously impaired friend as he itemizes the many kinds of people who might be counted (morally) ‘more blind . . . than we’: the virtuous and the sinful, misers and prodigals, the happy and the sad, the ambitious and the powerful, and even – more surprisingly and self-mockingly – poets and ‘the whole Court’.

Another category of the blind are the learned who see only through their books. This thought leads Huygens into a brief survey of contemporary scientific controversies. After all, one faction at least must be blind when there are both those who believe the Earth goes round the sun and those who believe the opposite. Alchemy, the circulation of the blood, and the mathematical conundrum of squaring the circle (or should one ‘round the square’?) get the same treatment. Even the science of vision has its controversial opposition, with some believing ‘our eyes are bows / That shoot out rays of light’ – a ‘vulgar lie’, Huygens adds.

Huygens reserves a little of his fire for another surprising group in Ooghentroost: ‘Painters call I blind . . . / . . . They see but through the palette, / And erect a Nature . . . sweet and pleasant: but do you think to read there / How grandmother Nature really is?’ When he wrote this, he was in fact more closely involved with painters than at any other time in his life, in his continuing capacity as the secretary and confidant of Amalia van Solms, who had announced her wish to commemorate her husband Frederik Hendrik with a grand hall of paintings in the Huis ten Bosch.

The room itself, now known as the Oranjezaal, was planned by Jacob van Campen, who had been the architect of Huygens’s own house. Among those contributing heroic scenes from Frederik Hendrik’s life were Gerard van Honthorst, Jacob Jordaens and Thomas Bosschaert, as well as Adriaen Hanneman, who had painted the Huygens family group. Huygens’s ‘discovery’, Jan Lievens, produced a painting of the Muses, but Rembrandt did not receive a commission. In general, Amalia and van Campen selected the painters on the basis of their stylistic closeness to Rubens, a somewhat old-fashioned preference that neglected the legion of Dutch artists working in new ways, but which was in tune with Huygens’s own taste, and more importantly with that of Frederik Hendrik, whose memorial this was.

Other than performing his secretarial function, Huygens himself played little part in furnishing the Oranjezaal. Perhaps it was just as well: he must have quailed when Amalia reappointed Gonzales Coques, the artist who had disgraced himself when he was caught out having subcontracted a previous commission for Frederik Hendrik to another painter.

![]()

Christiaan’s father often sought distraction in female companionship. The list of Constantijn’s women friends in the desolate years after the death of his Sterre would have made a veritable directory of Low Countries pioneers of feminism, had there been call for such a document in the seventeenth century.

The chief object of his poetic attention in the Muiden Circle, Tesselschade Visscher, died in June 1649. He had once marvelled when she came to stay with him in The Hague and slept in the room above his own, kept apart only by ‘my cold ceiling, and her cool honour’. But she caused him bitter disappointment when she turned to Catholicism and, although they stayed in touch until the end, he grieved wittily for the spiritual loss of ‘Beroemde, maer, eilaes! be Roomde Tesselscha’ (‘Famed, but, alas, be-Romed Tesselschade’).

His favourite singer, Utricia Ogle, the daughter of the English governor of Utrecht, Sir John Ogle, was another lifelong friend (her unusual name is a reference to the Dutch city of her birth). He called her his ‘bewitching little bird’, playing on the rhyme of the Dutch word for bird, vogel, with her maiden name. He delighted at the opportunity for further wordplay in the same vein when she married and acquired the name of Swann, and he became a friend of her husband too.

But unquestionably the most intellectual of Huygens’s women friends was Cologne-born Anna Maria van Schurman. Her father had taken the unusual decision that she should be educated alongside her brothers, and she became proficient in more than a dozen languages, as well as in theology, history, geography and mathematics. She also mastered many crafts, including paper-cutting, drawing, wood-carving and embroidery, and achieved particular distinction in the art of engraving on copper. In 1636 she was invited to write a Latin verse for the inauguration of the University of Utrecht, in which she made a point of recording that she herself was nevertheless disqualified from actually studying there. Thereafter, she was permitted to attend some lectures, though only if she sat screened from the gaze of the male students.

Huygens’s acquaintance with van Schurman dates from 1633, when she was twenty-six years old and becoming known for her verse in the leading poetic circles. She sent him a finely detailed gravure self-portrait in which she pretends to look bashfully aside as if seeking approval, while a suppressed smile knowingly suggests she needs no such thing. In front of her, she holds up a cartouche, which reads that, if she has not here made a good job of rendering her own features ‘in everlasting copper’, then she will not take on the ‘more important task’ of portraying anybody else. It was in effect a business card. Huygens replied with a dozen lines, teasing ‘the handless maid’ for hiding from view the instruments of her talent behind the cartouche.

Theirs was a meeting of minds above all. Huygens praised van Schurman’s polyglottism – which exceeded even his own – as ‘mannelijk’, or manly, the same complimentary term that he had once applied to his wife’s skills of project management. He asked her to review Dagh-werck, his long poem in celebration of domestic life, because he wanted a poet’s view as well as a woman’s. Huygens did not employ with Anna Maria the familiar, and sometimes risqué, language that he adopted with some of his other women friends. Instead, he addressed her in his Latin correspondence as ‘Nobilissima virginum’ and ‘N virgo’, or ‘Nobilissima domina, Amica nobilissima’. He valued her great learning and her broad network of contact with leading thinkers across Europe. Her declared celibacy intrigued him, but if he thought this was the price she paid for creative freedom (it was usual for women to give up poetry and other intellectual pursuits upon marriage), then it was one that he ultimately felt was too high. He believed that his own daughter, Susanna, had an intelligence such that ‘one could make a Schurman out of her’, but he avoided following Anna Maria’s father’s example when it came to her education.

A number of younger women went some way towards satisfying longings that Anna Maria van Schurman certainly did not. In 1652 Huygens was introduced to Béatrix de Cusance, the well-connected Duchess of Lorraine, who maintained a wide social network that included various royal families. She was another musician, and Huygens wrote keyboard pieces for her to play as well as a number of poems, often rich in double entendre. The most notorious of these is a riddle describing the removal of a corset, in which Huygens contrived the same rhyme to every line in the original French as he described his feelings – ‘I love it more than / Amber, civet and musk’ – leading up to the closing line’s invitation to ‘Guess whose is the busk’. Taking a chance, Huygens sent the poem off to her, and got no reaction at first, although later, Béatrix, who was ill-treated by her husband, told him she had been pleased to receive his attention.*

In their various ways, Béatrix, Utricia and Anna Maria were all untouchable ideals. Maria Casembroot, on the other hand, twenty-five years younger than Huygens, lively and beautiful, was able to brighten daily living in more immediate ways. She was the closest Huygens came to finding a true partner after the death of Susanna. Although she, too, was an able musician, Huygens accentuates her more down-to-earth qualities in verses where he plays on her name as kaas-en-brood, or bread-and-cheese.

Another young woman friend was Maria van Oosterwijck, the daughter of a church minister who moved to Voorburg when she was six years old. Huygens must have known of her early on, and was doubtless attentive when she began to show promise as a painter. She became extremely successful, and a number of courts in Europe acquired examples of her precise flower still-lifes. Her portrait painted when she was forty-one years old shows her as very beautiful still, with a broad mouth and face and fine black hair, holding her palette and brushes with an open book on her lap.

Whatever the nature of his relationships with these women, Huygens clearly adored female company, and never gave up trying to find it. In 1682, at the age of eighty-six and still going about on the business of the prince (the restored stadholder William III), he rode out one day, like Don Quixote, to Nijenrode Castle near Utrecht in a desperate courtship of one Maria Magdalena Pergens. Sadly for him, beautiful Leen, or Leentje, married another a few months later.

Though his badinage often appears to err on the side of bawdiness – when the Princess of Hohenzollern, Maria Elisabeth, could not play the lute for him because, she said, of the wide collar she was wearing, he parsed her refusal into the thought that ‘the princess never played better than when she was undressed’ – Huygens was always sincere in his personal interest, and the subjects of his attention understood this. He may have come across as an old goat at times, but he was also a true charmer, and none of his female associates ever severed her connection with him. His attitude of openness and generosity is apparent from the way that these connections were established in the first place. It was Utricia Ogle who introduced him to Anna Maria van Schurman; he introduced Maria Casembroot to van Schurman; he mentions Casembroot admiringly in letters to Utricia and Béatrix; in with an amorous letter to Utricia was also a note for ‘her Sibyl’, van Schurman; and so on. None of these intersections would have been likely if he had entertained a serious romantic interest in any one individual.

![]()

One more woman deserves notice here, for with her Huygens found common ground in the discussion of a scientific matter of intense contemporary interest. On 15 September 1653 Constantijn wrote to his musical friend Utricia Swann in raptures, having been introduced to Margaret Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle, whose husband was her cousin: ‘I am fallen upon this Lady, by the late lecture of her wonderful Book, whose extravagant atoms kept me from sleeping a great part of last night.’ The book was her newly published Poems and Fancies, which contained a long section setting out her ideas about atomic theory.

As a young woman, Margaret Lucas served as a lady-in-waiting to Henrietta Maria, the consort of King Charles I, at first in Oxford and then in exile in France during the English Civil War. In Paris, she married the widower William Cavendish, thirty years her senior, and like her from a resolutely royalist family. Now she found herself playing hostess to the city’s leading scholars. She met Descartes and mathematicians such as Pierre Gassendi and Gilles de Roberval (who would later become associates of Christiaan Huygens). Although her early education had furnished her with nothing more than the usual ladies’ accomplishments, her lively, inquisitive nature clearly appealed to such men. Through her correspondence with Mersenne, she became aware of other intellectuals across Europe, including Evangelista Torricelli, Hobbes and Constantijn Huygens.

Unable to return to England following the execution of Charles I, William and Margaret settled in Antwerp, where they lived in some style in Rubens’s old house, holding musical soirées to which other exiles and their new Dutch neighbours came. The sojourn on the continent must have greatly assisted Margaret’s development as a writer and thinker. She was still in her twenties in a land where women such as Huygens’s friends Anna Maria van Schurman and Tesselschade Visscher were at least not discouraged from learning. Emulating these women of letters, Margaret overcame her lack of formal education and dyslexia, and eventually wrote (with the assistance of a scrivener) many plays, poems, stories and – exceptionally for a woman at the time – several treatises on natural philosophy. She placed on record her regret that it ‘was not a woman that invented perspective glasses to pierce into the Moon’, and that there was no woman to equal Paracelsus, Galen or Vitruvius. Her most famous work, The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing-World, is an early example of utopian science fiction which imaginatively incorporates aspects of her autobiography, and has been acclaimed as a proto-feminist polemic.

Cavendish found it advantageous to cultivate a striking appearance in order to promote her work and became a well-known personage wherever she went. To this end, she designed her own extravagant and sometimes revealing clothes. Her later English nickname, ‘mad Madge’, may have some connection with the redoubtable battle-axe known as ‘dulle Griet’ or ‘mad Meg’ in a sixteenth-century Antwerp play (and subsequent Bruegel painting). This bravado was perhaps a means of compensating for shyness, but it was more likely a strategy to warn those whom she met to be ready to engage with an equally vibrant intellect. Some – especially men – were just distracted, but others successfully decoded the message. Dorothy Osborne, the wife of Sir William Temple, a future English ambassador to the Dutch Republic, wrote of Poems and Fancies: ‘this book is ten times more extravagant than her dresses’.

Huygens met Cavendish at least twice in Antwerp in 1657 and 1658, and they corresponded long afterwards. As a poet and playwright himself, and a keen follower of new science and philosophy, he became her leading admirer, happy to engage with the range of her ideas. Huygens was able to offer his new friend more than just moral support. Cavendish knew that her ideas needed to be communicated in Latin if they were to reach the greatest audience, but she had no language skills herself. Huygens, who was, of course, accustomed to reading and writing in Latin, became a vital adjutant, producing a Latin index of her work so that scholars in all countries might have access to it. His committed interest is evidence that Cavendish’s scientific work was taken seriously in its day, which some modern historians have assumed was not the case.

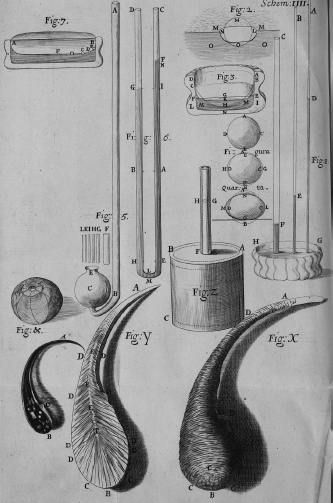

Their principal scientific dialogue concerned their mutual fascination with the phenomenon that came to be known in English as Prince Rupert’s drops. These were teardrop-shaped glass beads a couple of inches long which exhibited apparently paradoxical properties not seen in other forms of glass. The head of each tadpole-like bead was extremely strong, able to resist a sledgehammer blow. But if the tip of the tail was snapped off, the whole bead would explode, leaving behind only a scattering of sugar-like granules. It made for a dramatic opposition: the fragile beauty that glass objects always possess set against the potential for violent destruction.

Although the earliest drops date from 1625, they became more generally known around 1650 in Holland and Germany, where they were called Bataafse tranen, ‘Batavian tears’ or ‘Holland tears’. Their strange behaviour was demonstrated at Henri Louis Habert de Montmor’s circle of savants in Paris in 1656 and they quickly spread as a topic of speculation of natural philosophers across Europe. They became a widespread fad, however, and gained their English name when Prince Rupert of the Rhine brought some specimens to his cousin King Charles II and they were subjected to the experiments of the Royal Society. Their momentary fame was captured in the satirical ‘Ballad of Gresham College’ in 1663:

And that which makes their Fame ring louder,

With much adoe they shew’d the King

To make glasse Buttons turn to powder,

If off them their tayles you doe but wring.

How this was donne by soe small force

Did cost the Colledg a Month’s discourse.

On 12 March 1657, Huygens sought to discover Cavendish’s opinion concerning ‘the natural reason of these wonderful glasses, which, as I told you, Madam, will fly into powder, if one breakes but the least top of their tailes, whereas without that way they are hardly to be broken by any waight or strength’. He can have done no harm to her self-esteem when he added that neither the king of France nor ‘the best philosophers of Paris’ can explain it. Presuming that she would resort to a practical experiment, he advised her how to proceed to work safely with ‘these little innoxious Gunns’: ‘a servant may hold them close in his fists, and yourselfe can break the little end of their taile without the least danger. But, as I was bold to tell your Ex.cie, I should bee loth to beleeve, any female feare should reigne amongst so much over-masculine wisdom as the world doth admire.’

Cavendish responded with alacrity a week later, offering a detailed argument as to the possible cause of the phenomenon: ‘to myne outward sense these glasses doe appeare to have on the head, body or belly a liquid and oyly substance, which may be the oyly spirrits or essences of sulpher’. Sealed inside, the volatile liquid might escape with the force of an explosion when the tail is broken off. She arrived at this conclusion not only from direct observation of her own glass drops, which must have appeared hollow to her, but also, as she candidly explained, from a feminine familiarity with the glass orbs of earrings into which shreds of brightly coloured silk were often placed.

Huygens was not satisfied with this, however. Surely, he argued, if sulphurous liquor is encapsulated in the glass, a flame brought near will cause it to ignite. He had tried this, but it did not happen:

Madam, I found myself so farre short of my opinion, that firing one of these bottels to the reddest hight of heat, I have not onely seene it without any effect, but also being cooled againe, I have wondred to see all his vertue spent and spoiled, so that I could breake of the whole taile by peeces even to the belly, without any motion more then you would see in an ordinarie peece of glass.

Cavendish replied again, reasoning – less plausibly this time – that the contained liquor might have quenched the fire or leaked away as a vapour.

Thus, Sir, you may perceive by my argueings, I strive to make my former opinion or sense good, although I doe not binde myselfe to opinions, but truth; and the truth is that though I cannot finde out the truth of the glasses, yet in truth I am

Sr

Your humble servant

M Newcastle.

This correspondence is notable not so much for its resolution of a scientific puzzle – Cavendish and Huygens do not come close to a full understanding, as we shall see in a moment – but for the ready acquiescence to the Baconian scientific method by two intellectuals who, for all their many accomplishments, can hardly be thought of as ‘professional’ natural philosophers (as some of their contemporaries, such as Descartes, Robert Boyle and, of course, Christiaan Huygens, certainly were). They switch from hypothesis and experimental test and back like old hands in their search for the truth even when, as Cavendish admits, the truth is that they do not really know what is going on. Cavendish believed, in fact, that the truth cannot be fully known, and that natural philosophers can only speak in terms of probabilities, a position very similar to that which Christiaan would later come to articulate.

Though the Batavian tears were above all a curiosity, there were good reasons for wanting to know why they behaved as they did. Lenses for telescopes and microscopes typically began life as molten glass beads. Here, any irregularity of the glass medium as it solidifies is a cause for concern as it may impair optical quality. Some may have envisaged military uses for the little explosive devices, too. So it was not unnatural that members of the Royal Society among others should have wished to learn more about them.

The presentation given at Gresham College (the future Royal Society) in March 1661 was written up by the president, Sir Robert Moray, who had himself lived in exile during the Commonwealth years in the Dutch Republic and was familiar with the country’s glassworks. He closely observed five of the comma-shaped drops that Prince Rupert had given to the king, and which the king, out of admirable self-restraint or sheer ennui, had resisted the urge to tweak. Two of them appeared to contain liquid while the remaining three appeared solid. Although those who assembled for the demonstration had no special knowledge of how they had been made, an experimental assistant apparently had little difficulty in forming some additional drops, which were found to behave in the same way as the king’s gifts. The exhaustive series of tests included ‘detonating’ the drops underwater, surrounded by cement, in a fire, and in the vacuum of Boyle’s air pump.

It was Robert Hooke who best intuited the principle of their operation. He explained that as the glass suddenly cools upon being dropped into water, its surface forms a hard shell while the interior, slower to solidify, tries to contract, producing a great build-up of tension. (When Constantijn Huygens heated one of the drops during his exchange with Margaret Cavendish and found that it lost its explosive property, he had without knowing it converted the glass from a ‘tempered’ form like that used today in car windscreens to an annealed form without tension.) Differing rates of thermal contraction of the interior would account for the fact that some drops turn out hollow while others are solid. Hooke made a comparison with an arch to explain the distribution of forces within the curved surface of the drop, and in Micrographia included a drawing complete with fracture lines in the glass, which he was able to capture and sketch by triggering a drop to explode while held in place by fish glue.

Some members of the Royal Society did not pause to take in this analysis, or else they simply wished not to spoil a neat party trick with science.* At a dinner in January 1662, Samuel Pepys witnessed a repeat demonstration of ‘the Chymicall glasses, which break all to dust by breaking off the little small end – which is a great mystery to me’.

Pepys was all eyes, however, when Mad Madge paid a visit to the Royal Society a few years later. She was shown experiments related to light, magnetism and chemical solvents. Optics was another topic of discussion, Cavendish having disparaged the efforts of microscopists including Hooke, whose instruments she believed could reveal only a distorted picture of nature. It was the first visit by a woman to the society and exceptionally well attended, for Cavendish was by then a major celebrity. Pepys had recorded earlier in the month how he had seen her spectacular black and silver coach pursued through the park by other coaches and accompanied by ‘100 boys and girls running looking upon her’. But unlike Constantijn Huygens, he remained quite blind to her merit as a scientific intellectual. On the day of her visit to the Royal Society, 30 May 1667 (OS), he wrote in his diary: ‘The Duchesse hath been a good, comely woman; but her dress so antic, and her deportment so unordinary, that I do not like her at all, nor did I hear her say anything that was worth hearing, but that she was full of admiration, all admiration.’