10

NEW MUSIC

Music always sounded through the Huygens family home. On the Fridays when he was in residence, Constantijn hosted musical evenings, with neighbours and guests joining him in playing and singing while he himself stood ready to take up whatever instrument the ensemble required. When they were old enough, the children, too, were encouraged to participate in the amateur collegium musicum, and sometimes, it was noted, they performed even better than their father. As he grew up, Christiaan did not exclude music from the range of his scientific explorations, and the curious innovation he was to make in this field surely has its genesis in these domestic entertainments.

His father had shown an extraordinary aptitude for music from the beginning. At the age of two, he could repeat his mother’s singing the Ten Commandments to him in French. His formal musical education began at four, with a tutor who helped Constantijn and his brother Maurits identify the notes of the scale by assigning their values to the gilded buttons that ran up the sleeves of their winter coats. Constantijn proved to have the better ear and voice, and at six years old he began to learn the viol, or viola da gamba, which was soon followed by lessons on the lute, the harpsichord and the organ.

On a visit to Amsterdam as a young boy, Constantijn attended the soirée of a family friend where the music-making was led by Jan Sweelinck, the organist at the Old Church in the city and the most influential Dutch composer of the seventeenth century.

It happened that in the presence of a good company of men and women (who were surprised that I, while others had been making all kinds of mistakes, had never made an error the whole afternoon), I lifted my eyes from the line in the score and in my confusion and shame had no possibility of finding my place again. This little misfortune – indeed, I remember it exactly – dealt my childish enthusiasm such a heavy blow that I burst out in bitter tears and could not be persuaded to take up my viol a second time.

This mishap did not hold the young Huygens back for long. When, in his twenties, he travelled to England – the major centre for viol consorts – on his first diplomatic assignments, he fell in easily with the musical circles there and met other composers, such as Nicholas Lanier, the Master of the King’s Musick. In Venice, he heard Claudio Monteverdi conducting his work in St Mark’s, ‘the most perfect music I ever heard in my life’.

Music served many purposes for Huygens. It opened the door to friendship wherever he went, and the unforced appreciation with which his efforts were rewarded was perhaps all the more welcome for coming without the further obligations that tended to follow upon the heels of praise for his work at court. Often, it gave him access, both to intellectual and creative figures and to people with real influence who would be in a position to help him realize his master’s diplomatic goals. Constantijn had learned this useful lesson early on when he suddenly found himself playing for a delighted King James I. Huygens – a young man from a young republic – was clearly thrilled to have experienced a royal audience, but, equally clearly, he was not overwhelmed, either by the occasion or by the monarch himself, as he continued to play on unbidden in his presence.

Throughout Huygens’s long life, music-making was also a means of escape from daily cares. Often, as he told an English musician friend, he would use it ‘to fiddle myself out of bad humour’. When troubles mounted, music became more important, not less. At the end of the ‘disaster year’ of 1672 when France betrayed the Dutch Republic by joining England in war against it, Huygens wrote to this same correspondent that he found it vital to ‘sweeten the bitter displeasure of these times with some harmonious practise, as I can tell you I doe, and never will give over while I breathe’.

The recipient of these confidences was Utricia Swann, née Ogle, the most enduring of Huygens’s many female companions in music. For it was undoubtedly the case that Constantijn Huygens saw musical gatherings as a congenial way of meeting educated and talented women. The pattern was set in his bachelor years in the Muiden Circle of poets, where the beautiful Tesselschade would sing and play, and became more important for him after the death of his wife in 1637. These social occasions offered abundant opportunities for flirtation while sharing a keyboard or accompanying a song.

From Tesselschade onwards, many of Huygens’s women friends served him in the role of muse. But Utricia was clearly something rather more than this. A likely portrait of her by a follower of van Dyck shows a woman looking imperiously at us down her long nose and sidelong across her bare shoulder. With lips pursed, ringlets falling across her forehead and a rope of pearls around her neck, she projects the air of a diva. They first met in 1642 when Huygens was overseeing a visit to the Dutch Republic by Henrietta Maria, the wife of King Charles I, and mother of Mary, the child-bride of the future William II of Orange, and Utricia was one of her retinue. She soon charmed him by her appearance and her voice, prompting an outpouring of verse and new keyboard arrangements of songs he had heard her sing. When she sang in his garden at Hofwijck, he likened her sound to a nightingale, although another time she cried off an assignation, saying her tone had ‘a certaine tang like that of a paire of skates upon your ice’. The musical friendship intensified even after her marriage to William Swann, who was, like her father, an English officer in the Dutch army. Not three weeks after her wedding, Huygens wrote teasingly to her – crossing out an absent-minded ‘Mademoiselle’ and putting ‘Madame’ in its place, and referring ironically to ‘a season when I imagine that you would have “much adoe about nothing”’ – simply to milk her praise for his ‘musical productions’. When Huygens learned one time that they would be unable to meet for an extended period to make music together, he boldly proposed an alternative arrangement. ‘Since all our aural communications are ruined,’ he wrote, ‘I am minded to reconnect us in some manner by the sense of smell.’ Enclosed with the letter were a couple of pot-pourri sachets together with an instruction to place them in her bed so that her sheets and his might smell the same. If he overstepped the mark with such tokens, it was soon forgiven. Their contact intensified in the 1650s, Huygens’s letters often larded with musical offerings to tempt her to visit again.

His poetic rivals Hooft and Vondel might on occasion tease Huygens for his knotted, unmusical verse, but Huygens could take quiet comfort that he was a genuine composer as well as a versifier. Vondel called him ‘Holland’s Orpheus’. He wrote more than 800 musical compositions by his own count, although none survives in manuscript form and only a few were copied. The most important of these surviving works is Pathodia Sacra et Profana, a setting of twenty psalms in Latin together with a similar number of songs in Italian and French for solo voice with a basso continuo accompaniment that would be played on a lute or theorbo, with the option of additional players on other instruments. It was written for Utricia’s voice and is dedicated to her. Huygens arranged to have the work published anonymously in Paris in 1647, perhaps because he had a low opinion of the Dutch music scene – he tried and failed to get the stadholder’s court to sponsor more musical activity – but more likely because he felt it would be improper for a servant of the court to be seen seeking attention in his own right. When he played, too, he was at pains to stress his amateur status, not out of modesty but for fear of compromising his professional position as secretary to the stadholder. His compositions were, as he wrote to an English courtier in 1648, his ‘after-dinner diversions and, as you might say, my taking breath after the day’s work’.

The Pathodia was an unusual melange of European styles. Its Latin psalms are set in a traditional polyphonic manner with two independent melodic lines, while the Italian songs follow the simpler pattern of madrigals. The French songs are written in a more modern – that is, baroque – style with a freer singing line. Like Sweelinck before him, Huygens avoided setting Dutch to music, preferring languages more usually associated with the singing voice at the time. Some of the song texts are Huygens’s own and, as might be expected of a poet, the collection is more notable for its exploration of the possibilities of word-setting than for its compositional novelty.

Nevertheless, Huygens was interested in musical innovation. As a child, he learned music according to the new seven-tone scale rather than the older scale of six notes. In adulthood, he thought fit to offer a list – in verse couplets, of course – of criteria that a musical work should satisfy. The first two items on the list were that a piece should be ‘new’ and ‘pleasant to sing’. He also emphasized the new in purely instrumental music. He boasted that he had ‘created music that nobody had ever heard, but that was born in me without the slightest exertion’. In fact, Huygens’s musical achievement may have more to do with the enthusiastic way in which he distributed his work, thereby transmitting ideas he had heard in one place to be heard perhaps for the first time in another. The Pathodia thus may have played a role in facilitating the spread of basso continuo from Italy, where Huygens was presumably introduced to it, to France. His interest in originality reveals his modern sensibility, but perhaps this should be weighed against his mien as a diplomat, seeking harmony wherever possible, which may have caused him to play safe in his compositions. As in his thinking about scientific problems, Constantijn Huygens remained in his musical ideas awkwardly poised between old ways and the new.

Music in the Dutch Republic was also a moral issue. The Calvinist liturgy was generally confined to psalms sung – usually badly – by a single cantor. Organs in the churches were often owned by the city. Their music did not feature in the body of the religious service, but might sometimes be played before or afterwards. However, Constantijn Huygens, who was certainly as devout a Calvinist as the next man, loved music, and believed that hearing it and making it was ‘not unbecoming for persons of good standing and good birth’. He felt there was no reason why music should not be heard in a church of any denomination. In a pamphlet entitled Gebruyck of Ongebruyck van ’t Orgel (‘Use or Misuse of the Organ’), printed in 1641 – in which he took the opportunity to reaffirm that he had been ‘born, nurtured and trained against the public divisiveness of the tendency to Rome’ – he nevertheless argued for the readoption of organ music as part of Protestant services. Ever the diplomat, Huygens had first sent the potentially controversial text to leading figures whose opinion on musical matters he valued, including Amalia van Solms, Hooft and Descartes. The French philosopher struggled with the Dutch text, but recognized that Huygens was hoping to see the organ used very much as it was in Catholic services, and replied warmly that it might be the instrument ‘to rejoin Geneva with Rome’. This did not happen, of course, but during the next few decades, congregational singing with organ accompaniment did slowly come into vogue in Protestant churches.

Constantijn Huygens was fortunate to live long enough to see this transformation under way. He never tired of music-making or musical experimentation. The theorbo remained, as it long had been, his favourite instrument for playing at home, although when he was away on campaign he took with him the more practical lute. Lying on the table in his early portrait by de Keyser is a hybrid instrument combining the portability of a lute with the greater dynamic range of a theorbo. When he was well into his seventies, he tried out the guitar, but found it a ‘miserable instrument’. Two months before his death, he complained to a friend that gout was hampering his musical efforts, but he could still play the theorbo, ‘at least so, as the saying goes, a drunken farmer would not notice the difference’.

![]()

In these last years of his life, with most of his artistic friends long dead, Constantijn Huygens was comforted by the presence once again in the family homes of his favourite son, Christiaan.

Constantijn saw to it that the musical upbringing he had received was replicated for his children. Young Constantijn and Christiaan received instruction together. This education started at an early age when their father played the notes of the scale to each of them – only Christiaan was able to sing them back accurately and wished to know more. Less attention was paid to their younger siblings, even though the youngest, Susanna, may in fact have been the most naturally talented musician among them. Although the Huygens family was undoubtedly more committed than most, music was a standard feature in the education of any young gentleman or lady at this time. Not only was music one of the four subjects in the traditional quadrivium of the liberal arts, but harmonics, or the theory of music, was also considered one of the ‘classical sciences’, along with astronomy, optics, static mechanics and mathematics. Music thus also played a full and entirely expected part in the range of interests of men such as Galileo, Mersenne and Bacon. In the Low Countries, both Simon Stevin and Isaac Beeckman sought to contribute to the development of music theory. Prompted by Beeckman, Descartes, too, produced a treatise on music, even though by all accounts he could hardly tell a fifth from an octave.

Christiaan clearly enjoyed music, and musical parties were often held in his Paris apartment – he wrote of one such concert, where there were women ‘who sing very well, and play the harpsichord even better’. But he was rather less of a composer than his father. Although he and his brother occasionally wrote when the other was in Paris about the latest songs to be heard there, the practical production of music was not as important to him as understanding its fundamental mathematical structure. Like other scientific figures, he thought this was a prerequisite for further innovation in music. All that survives of any music he wrote is sixteen bars of the courante from a dance suite, along with odd snatches of notated melody scattered through the margins of his scientific notes. He had learned to sing and play the viola da gamba and the lute. However, he most often played the harpsichord, an instrument more usually taken by women in amateur musical circles, and it was at the keyboard that his interests took a more theoretical turn.

The human voice is able to sing by producing sound waves over a continuous range of frequencies. Many musical instruments, however, are designed to emit tones at fixed frequencies, according to the length of individual vibrating strings in the case of keyboards, or resonating columns of air in organs and wind instruments. Players of such instruments are thus governed by rules of temperament, which determine the relative magnitude of the intervals between successive notes in a scale.

Temperament has necessarily always been a concern of musicians, however they choose to acknowledge it. The number and spacing of notes in a musical scale (the graduated series of sounds into which an octave is divided, an octave being the musical term for a factor of two difference in sound frequency or pitch) is clearly a cultural decision. But underlying this is the sense of a natural or divine system of proportion which might guide instrument-makers’ choice of where to position individual notes (and which might, or might not, bear some relation to other proportional systems, such as the ‘harmony of the spheres’ supposedly exhibited by planetary orbits in the solar system). For example, the musical interval of a fifth is produced by the vibration of strings with lengths in the proportion 3:2. A system of tuning based on this ratio alone is attributed to Pythagoras, who is generally credited with being the first to notice that pleasant musical harmonies tend to be produced by vibrations of strings with lengths in simple ratios.

During the Renaissance and early modern period, the lost sounds of ancient music became a topic of avid speculation. Indeed, one of Christiaan Huygens’s first forays into musical theory, made in 1655, was a response to a book produced by a Danish music theorist, Marcus Meibomius, who had attempted to re-enact performances from ancient Greece. Huygens believed that the ancients must have used the octave and the fourth (based on string lengths in the ratio 4:3) and the fifth (3:2), but not the smaller interval of the third (5:4), which was thought to be less harmonious than the larger intervals.

The discovery during the seventeenth century that musical pitch (a qualitative index of how high or low a musical note is) is proportional to the frequency of vibration of the air produced by musical instruments – and therefore also inversely proportional to the more easily measured length of a string or pipe – set music theory on a solid quantitative footing. It was now possible to confirm that the musical intervals of Pythagoras were indeed based on exact ratios of the lowest numbers. Using this knowledge, some more mathematically inclined musicians now proposed to divide the octave in new ways that paid little heed to musical tradition. Stevin, for example, favoured a twelve-tone scale in which the pitch of successive notes increases or decreases logarithmically by exactly the same ratio (the twelfth root of two). This twelve-tone ‘equal temperament’ eventually became the most widely used tuning system in Western music, and is still the norm today. Others explored the division of the octave into even more tones. Such innovations held the promise of music that would sound entirely new. In 1627, in his utopian novel New Atlantis, Francis Bacon imagined, among many other scientific inventions, ‘sound-houses’ wherein ‘We have harmonies which you have not, of quarter-sounds and lesser slides of sounds’.

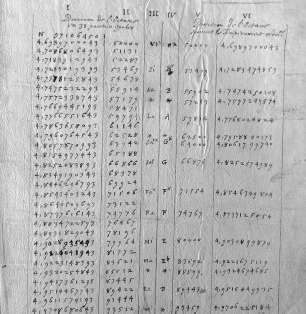

In October 1660 Christiaan Huygens had passed through Antwerp on his way to Paris. There he heard the spectacular new carillon installed by the Hemony brothers, bell founders who made carillons for many churches throughout the Low Countries, which may have stimulated his own decision to explore the division of the octave. Holding fast to Pythagorean fundamentals, he sought to express all the intervals needed by practising musicians in algebraic terms of the octave and the fifth only. After much calculation, beginning by splitting the octave into 100,000 equal subunits, Huygens found that the best fit could be effected by shifting the ratio of a fifth a little, from 100,000 / 66,666 to 100,000 / 66,874 (a shift of two cents in modern musical terminology, which is imperceptible to the human ear).* He reported on his work to his Scottish friend Robert Moray: ‘I have been busy for a few days working on music, and the division of the monochord [i.e. octave], to which I have happily applied algebra. I have also found that logarithms are of great use, which has caused me to consider these marvellous numbers and to admire the industry and the patience of those who have given them to us.’

Huygens’s hope was not to discover yet another mathematically ideal scale, like Stevin’s scheme, which was widely rejected by the subsequent generation of music theorists including Beeckman, Descartes and Mersenne, but to create something of practical use to musicians, and especially to keyboard players. He was convinced that pure ratios, 3:2, 4:3 and so on, gave the most pleasant-sounding intervals between notes. The difficulty was that not all these ratios could be produced precisely on a conventionally tuned keyboard.

Instrument-makers had to introduce various cheats in order to produce a usable keyboard. One such compromise system, called mean-tone temperament, attempted to privilege thirds by tuning them to lie equidistant between the octave and the fifth. However, this required the fifth to be slightly flattened, which some musicians found objectionable. By contrast, in the newer (but still unpopular) system of tuning to ‘equal temperament’ based on Stevin’s twelve-tone scale, all the intervals were somewhat impure, with fifths only slightly off but thirds more substantially so. This system, however, offered important advantages for practical music-making such as greater ease of modulation and transposition between keys.

Huygens did not favour twelve-tone equal temperament because its thirds were so far off true, but neither was he willing to accept the pragmatic alternative of ‘well-tempering’, which aimed to distribute the impurities in such a way that they affected the important intervals the least, because this approach was so makeshift. Instead, he wished to see a system that would achieve musicality while at the same time being underpinned by mathematical truth.

Proceeding further with his algebraic analysis of temperament during the summer of 1661 – his notes are strewn with little sketches and calculations of ratios to eleven significant figures – Huygens eventually found that he could divide the octave into thirty-one equal segments. In this scheme, each semitone is made up of two or three of these segments. The full octave then comprises the standard seven diatonic (white-key) and five chromatic (black-key) semitones as follows: (7 × 3) + (5 × 2) = 31. This system produced a close match with the aurally pleasing but previously unmathematical mean-tone tuning, and introduced the possibility of unlimited transposition between keys. It gave the fifth a ratio 31:18, the major third was 31:10 and the minor third 31:8. Other ratios had the potential to produce smaller intervals such as the ‘quarter-sounds’ imagined by Bacon.

This was not an entirely novel departure. Huygens was aware from his French mentor, Mersenne, of instruments with many more than the usual twelve keys per octave that had actually been built in Spain and Italy as long ago as the mid sixteenth century, but these reportedly sounded dreadful. The discovery since that date of logarithms made it possible to calculate the proper length of the strings more precisely (even if they could never be fitted to eleven significant figures of accuracy!) and promised a somewhat sweeter result. However, the prospect of sitting down to an instrument with thirty-one keys to the octave, and having to pick carefully among them simply to play an ordinary melody, was hardly likely to appeal to any real musician, and Huygens did not yet consider constructing such a keyboard, which he felt would be unplayable ‘without being confused by the multiplicity of white and black keys’.

But in 1669 Huygens returned to the question once more with renewed determination to find a practical solution. His answer was to fasten a conventional twelve-keys-to-the-octave keyboard by means of pins to an underlying keyboard comprising thirty-one pivots, which were connected in turn to the thirty-one strings within a given octave. With contact made between the keys on top and the pivots that came into alignment with them from below, the player would be able to strike the correct twelve strings for a given key as on any normal keyboard. Yet it would also be possible to reposition the top board elsewhere along the row of thirty-one pivots underneath in order to play tunes in other keys. In this way, the player would be able, with a certain effort, to transpose music more freely from one key to another.

Musical history, however, chose a different path. During the eighteenth century, twelve-tone equal temperament came to prevail for the simple reason that composers valued the ability to modulate between keys more highly than tonal purity.

Although the exact details of his design are not known, it seems that Huygens did have a specially adapted harpsichord built for him in Paris. On 10 July he wrote triumphantly to Lodewijk ‘that my harpsichord invention has succeeded very well, and I would not be without it for anything’. Sadly, the instrument has not survived, and Huygens’s only treatise on music, Le cycle harmonique, which was not published until 1691, reveals little additional information, confirming only that he experimented with a variety of instruments:

I have at other times made adjustments to such movable keyboards on harpsichords as there were in Paris, and even to those which had their ordinary keyboard, where it was necessary that what I put on top matched the heights of the white and the black keys so that the keys could slide without impediment. And this invention was admired and imitated by the great masters who found in it utility and pleasure.

One particular effect of Huygens’s retuned keyboard might have provoked a small revolution in music if the new instrument had been taken up more widely. His adjustment of certain musical intervals made some chords that had been conventionally regarded as dissonant sound more pleasing to the ear. Among these was the chord known as the tritone (because it was made up of two notes three whole tones apart; it is now termed an augmented fourth or a diminished fifth). The tritone had been infamous since the Middle Ages when it purportedly acquired the nickname of the diabolus in musica, or the ‘devil in music’, and was prohibited from use by church musicians. In Huygens’s tuning system, however, the chord suddenly lost its terror. Huygens himself judged it ‘harmonious upon attentive examination’ and employed it without compunction when he played his own harpsichord.

Christiaan Huygens’s experience with his novel keyboard illustrates some of the similarities and differences between father and son in their musical philosophy. Christiaan was more prepared to listen with an unprejudiced ear and more interested in the principles underlying musical effects. He clearly believed that innovation in music, as in other fields, represented an idea of progress. For example, in Cosmotheoros, his posthumously published meditation on extraterrestrial intelligence, he speculated that beings on other planets would hardly have a theory of music less advanced than our own, ‘neither can we presume that they want the use of half-notes and quarter-notes, seeing the invention of half-notes is so obvious, and the use of them so agreeable to nature’. Constantijn, meanwhile, was more concerned with musical output, in terms of both composition and performance, and was content to work within existing conventions and genres. As with their contrasting approaches to optical phenomena, the father was more captivated by the spectacle while the son sought fundamental understanding, reflecting the emergence during their two generations of a more rigorous idea of scientific method.

But Christiaan was not obsessed with the principles of music at the expense of its pleasures, many of which, he was sure, would remain inexplicable. He was adamant that the purpose of music was to please the senses and not to make gratuitous display of its artfulness. He favoured mean-tone temperament in the end not only because of its purer intervals, but also because it offered an appealing variation of character to sustain the listener’s interest when a melody was played in different keys. In this he was in complete harmony with his father, who in 1680 saw fit to remind Christiaan of ‘my couplet which gives the 6 things I require in all composition’. He ended by advising Christiaan to be true to what his own senses tell him: ‘I would be led ear-wise rather than nose-wise.’

![]()

Although the instrument Huygens had made for him in Paris no longer exists, an organ based on his original concept was built after the Second World War by a Dutch physicist, Adriaan Fokker. This instrument is now installed in the Muziekgebouw concert hall in Amsterdam, where it is regularly used for recitals, both of music from Huygens’s period and before, when these musical experiments were originally undertaken, and of contemporary works written specifically to showcase its microtonal capability. In place of Huygens’s detachable top keyboard, the Fokker organ has multiple keyboards arrayed in a colour-coded grid so that the player can alter pitch by quartertones simply by moving the hands vertically up or down from one row of keys to the next, while any one row of keys is played just like a standard twelve-note keyboard with its familiar white and black keys.

What does it sound like? In short, not as outlandish as you might expect. The one ‘universal constant’ of music is the octave – the fact that a tone at twice (or half) the frequency of another has a simple mathematical proportionality that we hear as related – although even this phenomenon is rather odd and without parallel in the other human senses. The only other fundamental consideration is how small a difference in the pitch or frequency of sound the human ear is able to detect. This varies according to the volume, pitch and quality of the sound (its timbre) as well as with the listener’s age and training, but is generally agreed to be about 0.5 per cent of the octave, equivalent to around two hertz in the middle of our auditory range. Over time, Western music has developed in such a way that, of the vast permutations theoretically available, only relatively few chords and sequences of notes have been deemed pleasant and permissible. A few other sequences and chords might be used sparingly, to project a sinister mood, perhaps, or to signal avant garde intentions, while many other possibilities have been simply ignored because of the fixed tuning of many musical instruments. Only in the twentieth century did composers begin to explore music based on quartertones and even smaller intervals, although most of their work has not entered the concert repertoire.

On the other hand, we are now more familiar than ever with the music of other cultures, from gamelan to blues, where different tonal laws apply. In addition, electric and electronic instruments are easily able to present sounds drawn from the continuous aural spectrum. This means that much of the music we hear today is microtonal, never more so than when it comes with the visual distraction of action on a screen. A celebrated example is heard in Stanley Kubrick’s film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, which makes use of several works of the Hungarian composer György Ligeti. The ‘micropolyphonic’ tones of his 1966 Lux Aeterna accompany the appearance of the black monolith that signifies the presence of a higher alien intelligence. That their music should sound like this is just what Huygens would have expected.