PUTTING THE DISCIPLINES INTO PRACTICE:

A Summary and Self-Assessment

Most executives spend considerable time and energy in search of competitive advantage, usually in areas like strategy, technology, marketing, and other fields that are based on intellectual property or capital. This is smart.

Unfortunately, the ubiquity and flow of information has reduced the sustainability of these types of advantages such that companies enjoy shorter periods of differentiation than ever before. This trend will certainly continue, and most likely it will accelerate.

However, there is one competitive advantage that is available to any company that wants it and yet is largely ignored. What is more, it is as sustainable as it has ever been because it is not based on information or intellectual property at all. What I am referring to is something I call organizational health, and it occupies a lot of the time and attention of extraordinary executives.

A healthy organization is one that has less politics and confusion, higher morale and productivity, lower unwanted turnover, and lower recruiting costs than an unhealthy one. No leader I know would dispute the power of these qualities, and every one of them would love his or her organization to have them. Unfortunately, most executives struggle with how to go about making this happen.

The first step is to embrace the idea that, like so many other aspects of success, organizational health is simple in theory but difficult to put into practice. It requires extraordinary levels of commitment, courage and consistency. However, it does not require complex thinking and analysis; in fact, keeping things simple is critical. It can even be summarized on a single page (see facing page).

The second step is to master these fundamental disciplines and put them into practice on a daily basis. The remainder of this book is dedicated to helping you understand how to do just that.

DISCIPLINE ONE: BUILD AND MAINTAIN A COHESIVE LEADERSHIP TEAM

Building a cohesive leadership team is the most critical of the four disciplines because it enables the other three. It is also the most elusive because it requires considerable interpersonal commitment from an executive team and its leader.

The essence of a cohesive leadership team is trust, which is marked by an absence of politics, unnecessary anxiety, and wasted energy. Every executive wants to achieve this, but few are able to do so because they fail to understand the roots of these problems, the most damaging of which is politics.

Politics is the result of unresolved issues at the highest level of an organization, and attempting to curb politics without addressing issues at the executive level is pointless. Although most executives I’ve worked with are aware of the existence of some political behavior within their teams, they almost always underestimate its magnitude and the impact it has on the company and its people.

This blindness occurs because what executives believe are small disconnects between themselves and their peers actually look like major rifts to people deeper in the organization. And when those people deeper in the organization try to resolve the differences among themselves, they often become engaged in bloody and time-consuming battles, with no possibility for resolution. And all of this occurs because leaders higher in the organization failed to work out minor issues, usually out of fear of conflict.

The commonness and severity of this problem make the point worth repeating. When an executive decides not to confront a peer about a potential disagreement, he or she is dooming employees to waste time, money, and emotional energy dealing with unresolvable issues. This causes the best employees to start looking for jobs in less dysfunctional organizations, and it creates an environment of disillusionment, distrust, and exhaustion for those who stay.

Cohesive leadership teams, on the other hand, resolve their issues and create environments of trust for themselves, and thus for their people. They ensure that most of the energy expended in the organization is focused on achieving the desired results of the firm. What is more, I have found that out-standing employees rarely leave these organizations.

What Does a Cohesive Leadership Team Look Like?

More than anything else, cohesive teams are efficient. They arrive at decisions more quickly and with greater buy-in than non-cohesive teams do. They also spend less time worrying about whether their peers will commit to a plan and deliver.

One of the best ways to recognize a cohesive team is the nature of its meetings. Passionate. Intense. Exhausting. Never boring.

For cohesive teams, meetings are compelling and vital. They are forums for asking difficult questions, challenging one another’s ideas, and ultimately arriving at decisions that everyone agrees to support and adhere to, in the best interests of the company.

Within the cohesive teams that I work with, members hold their peers accountable for behaviors that are not conducive to team performance. No one reads e-mail or does ancillary busywork during meetings, even when the issue on the table is not directly related to them. Everyone is involved and awake. If an issue hits the agenda and it is not compelling or critical, team members question whether it is worth their time.

Finally, cohesive teams fight. But they fight about issues, not personalities. Most important, when they are done fighting, they have an amazing capacity to move on to the next issue, with no residual feelings.

In those instances when a fight gets out of hand and drifts over the line into personal territory—and this inevitably happens—the entire team works to make things right. No one walks away from a meeting harboring unspoken resentment.

Unfortunately, many executive teams never achieve this. They yearn for easy, peaceful staff meetings as a retreat from their hectic schedules. What they end up getting are tedious and uninspiring show-and-tell sessions where department heads review the details of their responsibilities.

Is achieving cohesiveness difficult? Sure. A better question would be, “Is it worth the effort?” Whether you measure the results in terms of increased productivity, reduced turnover, higher quality of worklife, or simply less time in unproductive meetings, the answer is always a resounding yes.

How Is a Cohesive Leadership Team Built?

The most important activity is the building of trust, and one of the best ways to do this is what I call “getting naked.” This is not a New Age exercise involving group hugs and holding hands, but rather a general process of getting to know one another at a level that few groups of people—unfortunately, even many families—ever achieve.

There are many effective ways to get naked. No single method is enough, but none is specifically required. What is most important is that team members get comfortable letting their colleagues see them for who they are. No pretension. No positioning.

Although there are certainly unstructured approaches to building a cohesive team, I suggest taking a look at some of the proven methods and philosophies first.

- Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Often referred to as the MBTI, this is a profoundly effective tool for helping team members understand one another’s behaviors and avoid dangerous misattributions. It has been tested and used by millions of people, and there is no shortage of material relating to applying it to teams. I have found that even the most skeptical executive teams find significant, lasting benefit from using this tool.

- The Wisdom of Teams. Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith wrote one of the most compelling, no-nonsense approaches to building teams that I have seen. The Wisdom of Teams (and its companion volume, Teams at the Top) outlines the basic requirements for real teamwork and high-performing teams.

- The Five Temptations of a CEO. I wrote this book to help members of a leadership team self-identify their temptations and discuss how they might go about addressing them in the context of the team. It provides unique insights into the strengths and weaknesses of colleagues, especially as they relate to leadership within the context of an organization.

- Personal histories. Although it might sound like a “touchyfeely” exercise, I have found that it is remarkably helpful for members of a leadership team to spend time talking about their backgrounds. People who understand one another’s personal philosophies, family histories, educational experiences, hobbies, and interests are far more likely to work well together than those who do not. And given the large portion of our lives spent at work, getting to know peers on a meaningful level can go a long way toward making work fulfilling.

Now, achieving cohesiveness does not happen only during an off-site meeting or on a fixed schedule. In fact, a key part of building trust is about living through difficult times. Like a marriage or any other meaningful relationship, the only way to build strength is to share experiences that require everyone to rally and overcome obstacles. The most cohesive teams I know have faced ugly issues and even come dangerously close to dissolution. But by surviving, they develop a level of trust that is hard to break. The key for a leader is to remind team members why difficult times are worth tolerating, and what the rewards will be.

Once a team has achieved some level of cohesiveness, its ability to maintain it rests on its willingness to continually address core issues, and its discipline around having regular, frequent, and in-person meetings. While travel schedules and demanding workloads make it more and more difficult to get together regularly, it is nevertheless critical that an executive team not give in to the temptation to scale back meetings. Failing to honor meeting schedules, something that is all too common in most organizations, is the first sign that a leadership team is about to experience problems.

In terms of the effectiveness of a particular team, my experience indicates that a group’s cohesiveness has far more impact on success than its collective level of experience or knowledge. I have worked with leadership teams filled with industry luminaries and accomplished executives who could not compete with less experienced and relatively unknown teams that were able to create environments of trust and passion. Quite simply, cohesiveness at the executive level is the single greatest indicator of future success that any organization can achieve.

How Do You Assess Your Team for Cohesiveness?

Ask yourself these questions:

- Are meetings compelling? Are the important issues being discussed during meetings?

Every company has interesting, difficult issues to wrestle with, and a lack of interest during meetings is a pretty good indication that the team may be avoiding issues because they are uncomfortable with one another. Remember, there is no excuse for having continually boring meetings. - Do team members engage in unguarded debate? Do they honestly confront one another?

Every executive team should be engaged and passionate about what it does, regardless of its business. Even teams that get along well together should be experiencing regular conflict and intense debate during meetings.

If this is not the case, it is likely that there is a lack of trust, and an unwillingness to confront one another. Even the best teams have moments when members need to hold one another accountable for their attitudes or actions. Holding back during these times is a sure sign of future problems for the team. - Do team members apologize if they get out of line? Do they ever get out of line?

When people confront one another, discomfort inevitably occurs. Sometimes people get emotional; sometimes they say things they don’t mean. When this happens, it is key that they are comfortable apologizing to one another. As soft as it may seem, teams that can genuinely forgive and ask forgiveness develop powerful levels of trust. - Do team members understand one another?

Members of cohesive teams know one another’s strengths and weaknesses and don’t hesitate to point them out. They also know something about one another’s backgrounds, which helps them to understand why members think and act the way they do. - Do team members avoid gossiping about one another?

Talking about a colleague who is not present is not gossip. Gossip requires the intent to hurt someone, and it is almost always accompanied by an unwillingness to confront a person directly with the information being discussed. Ironically, members of cohesive teams are not overly concerned about the prospect of their colleagues’ discussing them in their absence because they know it is in the best interest of the team. They trust each other, and know that true gossip will not be tolerated.

If you answered no to any of these questions, you may have identified an opportunity to make your team more cohesive. The best way to begin this process is to discuss the questions presented here with the members of your team and ask them what their answers would be. Getting members to agree on which of these issues is most challenging for the team is the first step toward addressing it.

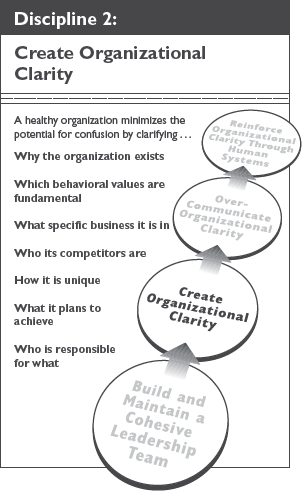

DISCIPLINE TWO: CREATE ORGANIZATIONAL CLARITY

Most executives profess to understand the importance of creating clarity in their organizations, but ironically, they often fail to achieve it. Maybe that’s because it is deceptively familiar.

After all, management consultants and strategy experts have been talking about mission statements, goals, objectives, and values for years, spawning a cottage industry of poster makers who decorate corporate hallways with vacuous statements about customers, quality, and teamwork.

But organizational clarity is not merely about choosing the right words to describe a company’s mission, strategy, or values; it is about agreeing on the fundamental concepts that drive it.

Why is this so important? Because it provides employees at all levels of an organization with a common vocabulary and set of assumptions about what is important and what is not. More important, it allows them to make decisions and resolve problems without constant supervision and advice from managers. Essentially, organizational clarity allows a company to delegate more effectively and empower its employees with a true sense of confidence.

What Does Organizational Clarity Look Like?

An organization that has achieved clarity has a sense of unity around everything it does. It aligns its resources, especially the human ones, around common concepts, values, definitions, goals, and strategies, thereby realizing the synergies that all great companies must achieve.

The result is an undeniable sense of focus and efficiency, concepts that even the most quantitatively oriented leader can embrace. When employees at all levels share a common understanding of where the company is headed, what success looks like, whom their competitors are, and what needs to be achieved to claim victory, there is a remarkably low level of wasted time and energy and a powerful sense of traction.

Employees in these organizations seem to have amazing levels of autonomy. They know what their boundaries are and when they need guidance from management before taking action. Their ability to make decisions for themselves creates an environment of empowerment, traction, and urgency.

If this is so powerful, then why don’t all executives create clarity in their organizations? Because many of them overemphasize the value of flexibility. Wanting their organizations to be “nimble,” they hesitate to articulate their direction clearly, or do so in a less than thorough manner, thus giving themselves the deceptively dangerous luxury of changing plans in midstream.

Ironically, truly nimble organizations dare to create clarity at all times, even when they are not completely certain about whether it is correct. And if they later see a need to change course, they do so without hesitation or apology, and thus create clarity around the new idea or answer.

Behaviorally, achieving real clarity in an organization requires an executive team to demonstrate commitment and courage. The teams I have worked with that do this are not necessarily smarter than their competitors, nor are they more experienced within their industries. However, they are definitely less afraid of being wrong.

So, as common as mission and vision statements are in most companies, few organizations achieve real clarity. This is unfortunate because clarity provides power like nothing else can. It establishes a foundation for communication, hiring, training, promotion, and decision making, and serves as the basis for accountability in an organization, which is a requirement for long-term success.

How Does an Organization Go About Achieving Clarity?

One of the best ways to achieve clarity is to answer, in no uncertain terms, a series of basic questions pertaining to the organization:

- Why does the organization exist, and what difference does it make in the world?

- What behavioral values are irreplaceable and fundamental?

- What business are we in, and against whom do we compete?

- How does our approach differ from that of our competition?

- What are our goals this month, this quarter, this year, next year, five years from now?

- Who has to do what for us to achieve our goals this month, this quarter, this year, next year, five years from now?

While some of these questions might seem esoteric and others tactical, all of them are important. The key is that at any given point in time, a healthy organization can point to an unambiguous answer for each question. Without those answers, confusion and hesitation begin to invade an organization.

One key to achieving organizational clarity is focusing on the essence of each question and not getting bogged down by the temptation to wordsmith the answers. Executive teams often lapse into “marketing mode” while discussing clarity, and start thinking about creating external marketing messages and tag lines rather than getting agreement around the basic concepts themselves.

In addition to this general distraction, each of the questions carries its own unique challenges, which are explored in detail in this section.

Why Does the Organization Exist, and What Difference Does It Make in the World? The challenge with this question is convincing a skeptical executive team that its answer has relevance for the organization and for the daily activities of employees. Though it may at first seem esoteric, it sets the stage for almost every decision the organization makes.

A successful Internet consulting firm I work with claims that it exists to help people realize their ideas. It believes that it makes a difference in the world by bringing start-up companies to life and giving people opportunities to work and invent new ways of doing business. As nice as this may sound, it is valuable only because the firm uses it to guide many of its decisions. When the company acquired two smaller firms, it chose them because they shared its enthusiasm for realizing dreams. When it evaluates new projects, job applicants, new markets, and new strategies, it always asks itself whether there is a fit with its underlying reason for being. The executive team attributes much of its success to the clarity it has achieved around why the company exists and its ability to adhere to it over time.

A clear explanation of this general principle comes from the work of Jerry Porras and Jim Collins in their book Built to Last. They describe the concept in detail and provide examples of companies that were able to articulate their core reason for being, as well as their core values, which is the focus of the next question.

What Behavioral Values Are Irreplaceable and Fundamental? The key to answering this question lies in avoiding the tendency to adopt every positive value that exists. Many companies I’ve worked with want to claim that they are equally committed to quality, innovation, teamwork, ethics, integrity, customer satisfaction, employee development, financial results, and community involvement. Although all of these qualities are certainly desirable and might even exist in a single company at a given time, the search for fundamental values requires a significant level of focus and introspection, and a willingness to acknowledge that all things good are not necessarily essential to an organization.

In fact, the healthiest organizations identify a small set of values that are particularly fundamental to their culture, and adhere to those values without exception. It is not that they reject all other values, but rather that they know which qualities lie at the heart of whom they are. This knowledge makes decision making easier and gives employees, customers, and shareholders an accurate picture of what the company represents.

In Built to Last, Porras and Collins provide many examples of how companies identify and use core values to guide the decisions they make. They make a point that I believe is worth repeating here: fundamental values are not chosen from thin air based on the desires of executives; they are discovered within what already exists in an organization.

One way that I help executive teams identify their fundamental values is by asking them to think about the two or three employees whom they believe best embody what is good about the firm. These would be people whom they would gladly clone again and again, regardless of their responsibility or level of experience. Then I ask them to write down one or two adjectives that describe the employees they selected. Usually a relatively short list of common or related terms surfaces.

To help them solidify their thinking, I then ask them to identify the one or two employees who have left the firm, or should leave the firm, because of their behavior or performance. Coming up with these names never seems to take long. Again, I ask them to write down one or two adjectives that describe the people they chose. Almost without fail, the same adjectives appear on most team members’ lists, and these often embody the antithesis of the company’s fundamental values.

Another approach to identifying values involves focusing on the common behavioral values of the people who founded the organization. This can be particularly useful in relatively new companies where there is little opportunity to reflect on past and current employees.

Now, the wrong way to determine an organization’s values is to survey the employee population. This may seem to be a useful way to test a hypothesis, but it is not a replacement for the introspection and discussion of an executive team. More important, it can lead to the adoption of a value set that executives are not willing to support.

These are just a few ways that an executive team can go about identifying its values. Whatever method is used, it is important to remember that the process should not be hurried, and initial answers should be tested and reality-checked before being communicated to the organization at large.

What Business Are We in, and Against Whom Do We Compete? I believe that a company cannot be called great if virtually every employee, and certainly every executive, cannot articulate the basic definition of what the company does. As simple as this seems, it is common to encounter employees in most companies who are not sure how to describe or define their organization’s basic mission.

By the way, that word mission often creates confusion. Some people think a mission is a lofty statement of ideals, others define it as an organizational goal, and still others call it a business definition. I recommend that any organization that shares this confusion stop using the term altogether and come up with a different term instead.

Whatever term it chooses, a company needs to be able to articulate exactly what it does, whom it serves, and against whom it competes. Why? Because all employees should be made to feel like salespeople or ambassadors for the firm, and they cannot do this without a fundamental understanding of an organization’s business. More important, without this understanding, employees cannot connect their individual roles to the overall direction of the larger organization.

How Does Our Approach Differ from That of Our Competition? Essentially this is a strategy question. Most companies I have encountered have different ways of defining and approaching strategy. Unfortunately, in spite of the fact that strategy is such a popular topic within business schools and in business media, there is no clear and simple definition of what it means.

I believe that an organization’s strategy comprises nothing and everything. By that I mean that no single concept can summarize a company’s strategy, yet every decision that a company makes contributes to or is a function of its strategy.

Take Southwest Airlines, for instance. If you were to ask most people what SWA’s strategy is, they would claim one of the following: low fares, on-time arrivals and departures, great service, regional routes. Give them a few more minutes and they’ll add more to the list: no frills, no first class, no preassigned seating, and humorous flight attendants who wear shorts. Which of these many attributes, all of which are true by the way, make up Southwest’s strategy? They all do.

Certainly the first few would be considered the company’s strategic anchors, but every decision that the airline makes, even allowing its employees to wear shorts, is connected to the strategy. And what is more, it is the collection of those decisions that differentiates Southwest from other airlines. Low fares alone does not differentiate them. On-time performance doesn’t either. But by combining these qualities with the others, it becomes very clear that Southwest has chosen a strategy that sets it apart from its competitors. Every organization should be able to be so clear.

The key is taking the time to look at all of the decisions that the company has made, even the obvious ones, and identify those that, when combined, make the company uniquely positioned for success.

What Are Our Goals This Month, This Quarter, This Year, Next Year, Five Years from Now? Because of the inconsistent use of the term, goals present organizations with another problem. That is why it is important to distinguish different types of goals from one another and use terms that eliminate confusion.

At the highest level, an organization should have one or two basic thematic goals for a given period. These might include survival, efficiency, professionalism, or growth. Whatever it is, the purpose of a thematic goal is to rally employees, regardless of their specific jobs, around a common direction. A good way to arrive at a thematic goal is to finish the following sentence: “This is the year that our organization will . . .”

Beneath a thematic goal there should be major strategic goals that span the organization and support its overall theme. For instance, if an organization’s thematic goal is growth, then its major strategic goals might include increasing revenue, adding new customers, hiring new employees, expanding to new sites, increasing market awareness, and improving infrastructure. If the thematic goal were survival, the categories might be achieving financial stability, retaining employees, retaining customers, and improving public relations.

Like so many other aspects of clarity, the key here is to focus on the areas that matter most and to avoid making every possible topic an area of equal importance. For example, even a company that is growing needs to retain its employees. However, employee acquisition may be the most relevant category to focus on and deserves more attention. Similarly, a company in survival mode certainly is interested in acquiring new customers, but it may want to place customer retention under a brighter spotlight for a given period.

Within each of these goals, an organization must be explicit. How many new customers? By when? From which regions? Getting specific about exactly what needs to be achieved, even in the face of uncertainty, is one mark of a healthy organization.

Finally, strategic goals need to be aligned with an organization’s permanent measures of success, which are metrics. For instance, virtually every organization should constantly have quantitative objectives related to permanent topics like revenue, expenses, profit, employee turnover, employee satisfaction, and productivity. These objectives become the means for keeping score over time and for evaluating the success of the actions within each of the thematic categories.

Many organizations make the mistake of using metrics in place of thematic and strategic goals. This is a problem because metrics do not inspire enthusiasm among employees, nor do they align behaviors around common themes or strategies.

Here, in summary, are the levels of goals that healthy organizations must embrace:

| Thematic goals: | What is this period’s focus? |

| Major strategic goals: | What are the key areas which relate to that focus, and exactly what needs to be achieved? |

| Metrics: | What are the ongoing measures that allow the organization to keep score? |

Once an organization has clarified these areas, it can call on its various departments to build their own goals, in a manner that is aligned with the direction of the entire organization. This requires that an executive team set its goals relatively early and avoid the temptation to waffle about what it wants the organization to achieve.

Who Has to Do What for Us to Achieve Our Goals for This Month, This Quarter, This Year, Next Year, Five Years from Now? One of the greatest problems that organizations encounter when it comes to achieving clarity is the inability to translate company goals into concrete responsibilities for members of an executive team. As fundamental as this activity would seem, most organizations don’t do a good job of breaking down their goals into clear deliverables for team members. This is partly due to the fact that they make dangerous assumptions about roles based on people’s titles, and because they shy away from difficult territorial conversations about who is truly responsible for what.

Every executive has his or her own preconceived notions about the difference between a sales vice president and a marketing vice president. However, when it comes time to assign responsibilities for specific goals, it is necessary to throw those assumptions out the window and look at each situation in terms of who would be the most appropriate owner, and why.

In some cases, roles are unclear because executive teams begin the process of establishing individual responsibilities before organizational goals have been set. The key to avoiding this situation is to take the strategic goals that have been set for the organization and then ask, “What has to happen in order for us to achieve each goal?” Each strategic goal will have many subgoals, and ownership for each of those should be explicit.

Only when each goal is broken down into components and ownership has been assigned to appropriate executives can accountability be achieved. When a goal might seem to be the responsibility of a collection of executives, it is still necessary to designate one person as the owner of that goal. Without clear ownership, accountability becomes difficult, even within the best teams.

It is worth repeating here that one of the keys to achieving clarity in this area is the willingness to engage in constructive conflict about who is best suited for which roles, and to sustain that conflict until agreement has been reached. This applies to every other area of clarity too. As you can imagine, without discipline one, this is virtually impossible.

How Do You Assess Your Organization for Clarity?

This is pretty simple. Ask your team members to individually answer the questions set out in this section. It is useful to have them write their answers down. Then go around the table and have everyone report their answers to the rest of the team. Fundamental differences will be painfully apparent. Keep in mind that it is okay for people to use slightly different language when they answer the various questions. What you are looking for is conceptual agreement.

DISCIPLINE THREE: OVER-COMMUNICATE ORGANIZATIONAL CLARITY

Once the executive team has achieved clarity, it must then communicate that clarity to employees. This is the simplest of the four disciplines, but tragically, the most underachieved. Why is this tragic? Because after having done all the work associated with disciplines one and two, it is a shame not to reap the benefits of those achievements. Especially when it is so simple.

What Does Over-Communication Look Like?

Within companies that effectively over-communicate, employees at all levels and in all departments understand what the organization is about and how they contribute to its success. They don’t spend time speculating on what executives are really thinking, and they don’t look for hidden messages among the information they receive. As a result, there is a strong sense of common purpose and direction, which supersedes any departmental or ideological allegiances they may have.

Employees in healthy organizations may joke, or sometimes even complain, about the volume and repetition of information that they receive. But they’ll be glad that they are not being kept in the dark about what is going on.

How Does an Executive Team Effectively Over-Communicate?

The first step is to embrace the three most critical practices of effective organizational communication: repetition, simple messages, and multiple mediums. Ironically, these have nothing to do with presentation style or speaking ability.

Repetition. The issue here has to do with the fear of repetition. Most executives I work with don’t like to repeat the same message again and again over time. This is because they are relatively intelligent people who don’t want to underestimate the intelligence of their audience. And so they make the dangerous assumption that once a message has been heard, it is both understood and embraced by employees.

Other executives complain about repetition because they are bored with a message after communicating it once or twice, and want to move on to solve the next problem within the organization. They enjoy the problem solving and find little intellectual stimulation in repetitive communication.

Unfortunately, effective communication requires repetition in order to take hold in an organization. Some experts say that only after hearing a message six times does a person begin to believe and internalize it. Even if that number is just three, consider how many times an executive would have to communicate a message before every employee in the organization will have heard it three times.

This problem is extremely common in organizations where I have worked. Almost without exception, executives lament having to repeat the same “tired” messages. In the next breath, they complain that employees are not hearing and acting on the messages they communicate.

One of the keys to successful communication, I remind them, is getting used to saying the same things again and again, to different audiences, and in slightly different ways. Whether they are bored with those messages is not the issue; whether employees understand and embrace them is.

Simple Messages. Another key to effective communication is the ability to avoid overcomplicating key messages. Years of education and training make most leaders feel compelled to use all of their intellectual capabilities when speaking or writing. While this is certainly understandable, it only serves to confuse employees.

That is not to say that employees are simple people, but rather that they are inundated with information every day. What they need from leaders is clear, uncomplicated messages about where the organization is going and how they can contribute to getting there.

How does a leader go about providing the detail and context for those messages? That brings us to the final communication challenge: the use of multiple mediums.

Multiple Mediums. All too often, executives feel comfortable using just one form of communication to convey messages to the rest of the organization. Some leaders prefer live communication, either to large groups or in more intimate settings. Others feel more comfortable writing messages through e-mail or intranet postings. Still others prefer to communicate primarily to their direct reports, who are then charged with relaying messages to employees deeper in the organization.

Which of these methods is best? All of them. Relying on one or two channels of communication within an organization will guarantee that some parts of the employee population will miss key messages. This is because employees also have preferences about the way they receive information.

Engineers might prefer e-mail, salespeople often find voice mail more convenient, some employees want to hear their leaders in person, and still others are fine with an occasional update from their manager.

Although I believe that any organization needs to establish standards about how most information is disseminated, it should not do so at the expense of using all types of media to convey key messages. Even if employees could somehow be retrained to use and embrace the same forms of communication, all methods should be used because each provides an executive with a unique opportunity to reach employees and make messages clear.

For example, live communication provides opportunities for meaningful interaction and emotional context; e-mail allows for more extensive information to be received and maintained for later review; and relayed communication from an employee’s manager creates an opportunity for in-depth discussion about how the message will affect people’s daily jobs.

In spite of the validity of each of these mediums, there is one form of communication that I have found to be the most powerful and underused within organizations of all sizes, from twenty-five to ten thousand employees. I call it cascading communication.

After virtually every executive staff meeting that takes place in any organization, there are key decisions that have been made and issues that have been resolved, which need to be communicated. Unfortunately, the executives often leave those meetings with different interpretations of what has been decided and what is to be communicated.

I once witnessed an executive team leave a staff meeting after deciding to establish a hiring freeze throughout the company. Fifteen minutes after the meeting had ended, an e-mail message went out from the head of human resources to all employees, informing them that all job requisitions were to be placed on hold until further notice. Five minutes later, two executives from the staff meeting were in the HR VP’s office, protesting that they thought the hiring freeze did not apply to their divisions.

The key is to take five minutes at the end of staff meetings and ask the question, “What do we need to communicate to our people?” After a few minutes of discussion, it will become apparent which issues need clarification and which are appropriate to communicate. Not only does this brief discussion avoid confusion among the executives themselves, it gives employees a sense that the people who head their respective departments are working together and coming to agreement on important issues.

Even when executives agree on what has been decided, there may be a wide range of viewpoints about how and how much to communicate to employees. Some executives sit down with their direct reports within a day of the meeting and fill them in on all the issues that they need to carry down to their people. Others leave voice-mail messages for their staffs, highlighting a few points. Still others communicate messages individually, on the basis of which items are relevant to which people.

This discrepancy in approach causes inevitable problems. Eventually some employees hear about executive decisions from their colleagues in other organizations, and they wonder why they aren’t being kept in the loop.

How Do You Assess Your Organization for Effective Over-Communication?

This is pretty simple. Ask employees if they know why the organization exists, what its fundamental values are, what business it is in, whom its competitors are, what its strategy is, what the major goals for the year are, and who is responsible for doing what at the executive level. Then ask them how their job affects each of these areas. Blank stares and incorrect answers are good signs that more communication is needed.

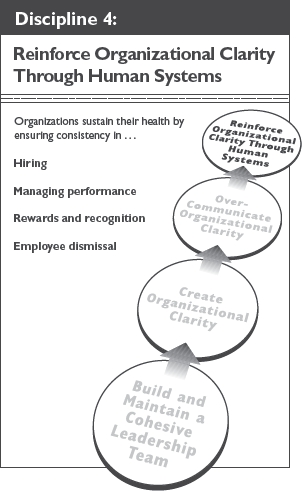

DISCIPLINE FOUR: REINFORCE ORGANIZATIONAL CLARITY THROUGH HUMAN SYSTEMS

Even a company dedicated to over-communication cannot maintain organizational clarity through communication alone. It needs to build a sense of that clarity into the fabric of the organization through processes and systems that drive human behavior. The challenge lies in doing this without creating unnecessary bureaucracy.

What Does Reinforcement Through Human Systems Look Like?

An organization that uses human systems properly maintains its identity and sense of direction even during times of change. It ensures that employees will be hired, managed, rewarded, and, yes, even fired for reasons that are consistent with its organizational clarity.

There are four primary human systems that serve to institutionalize an organization’s sense of clarity.

Hiring Profiles. One system is an interviewing and hiring profile, which is based largely on the fundamental values of an organization. Healthy organizations look for qualities in job candidates that match the values of the company. They ask behavioral questions of interviewees and probe for evidence that the candidate has the potential to fit within the organization.

After interviews have taken place, interviewers debrief with one another, paying special attention to the assessments of colleagues regarding the candidate’s alignment with fundamental values. This group consultation helps organizations avoid making costly hiring mistakes, which take months and sometimes years to correct.

Contrast this to most organizations where hiring is done in a “Did you like him?” manner. Interviewers make decisions based on their gut-level reactions to candidates, and with relatively little objective criteria about whether the employee matches the organization’s culture. Instead, they rely on résumé items and technical skills, which alone are poor indicators of future success.

Performance Management. Another system that serves to reinforce an organization’s clarity is its performance management process. This is the structure around which managers communicate with and direct the work of their people. It serves to help employees identify their opportunities for growth and development, and to constantly realign their work and their behaviors around the direction and values of the organization at large.

Unfortunately, most organizations place the wrong kind of emphasis on performance management, and in the process they lose the true essence of what performance management is about: communication and alignment.

There are two common misapplications that cause this to happen. Many companies make their systems too complex, requiring managers and employees to complete endless and complicated forms and numerical assessments. Too often, any sense of real management communication and coaching is lost among the instructions and requirements.

Another common problem has to do with the generic nature of many performance management systems. Too many companies purchase off-the-shelf systems designed by consulting firms whose sole purpose is to sell as many of the same forms to as many different companies as possible. It is little wonder that managers and employees alike see little value in taking time to complete them.

The best performance management systems include only essential information, and allow managers and their employees to focus on the work that must be done to ensure success.

There is relatively little emphasis on legal issues and quantitative evaluations, which often distract employees from the critical messages their managers are trying to communicate. What is more, these systems are customized to provoke meaningful discussion between managers and employees about relevant issues that they are dealing with on a daily basis.

Finally, performance management is not just about communication during employee review cycles. It is about ongoing dialogue around how employees can align their behaviors around the organization’s clarity.

Rewards and Recognition. This system has to do with the manner in which organizations reinforce behavior. Healthy organizations eliminate as much subjectivity and capriciousness as possible from the reward process by using consistent criteria for paying, recognizing, and promoting employees.

Decisions about bonuses and other compensation are based on the same criteria used in hiring and managing performance. This helps employees understand that the best way to maximize their personal rewards is to act in a way that contributes to the company’s success, as defined by organizational clarity.

In addition to monetary rewards, recognition of employees is designed around the organization’s values. These not only provide incentives for employees to emulate the right behaviors, but they also serve as a high-profile means of promoting the values themselves.

Finally, no one is promoted in healthy organizations unless they represent the behavioral values of the organization. Management discusses candidates for promotion not only in regard to their contribution to the bottom line but also in terms of their impact on reinforcing the clarity of the organization.

Dismissal. Healthy organizations use their values and other issues related to organizational clarity to guide their decisions about moving employees out of the company. Not only does this provide an effective means for identifying problems before they become too costly, it helps companies avoid making arbitrary decisions about an employee’s suitability for remaining within the organization.

How Does an Organization Assess Itself for Human Systems?

Answering the following questions is a good start:

- Is there a process for interviewing candidates and debriefing those interviews as a team?

- Are there consistent behavioral interview questions that are asked across every department?

- Is there a consistent process for managing the performance of employees across the organization?

- Do we spend time evaluating employees’ behavior versus the organization’s values and goals?

- Do managers and employees willingly participate in the system?

- Is there a consistent process for determining rewards and recognition for employees?

- Is there a consistent process for evaluating promotion candidates against organizational values?

- Are there consistent criteria for removing employees from the organization?

- Are employees ever terminated because they are a poor fit within the organization’s values?

While even the best organization may not be able to answer yes to each of these questions, more than a few no answers is probably an indication that better systems are needed to reinforce the organization’s clarity. Organizations should continually strive to create exactly the amount of structure that is required—no more and no less.

CONCLUSION

The model described here is a holistic one: each discipline is critical to success. And because every organization is different, each will struggle with different aspects of the model.

Some leadership teams have an easier time building trust than others but lack the discipline and follow-through to put processes and systems in place. Others enjoy strategic planning and decision making but lose interest in repeatedly communicating their decisions to employees.

Whatever the case, executives must keep two things in mind if they are to make their organizations successful. First, there is nothing more important than making an organization healthy. Regardless of the temptations to dive into more heady and strategically attractive issues, extraordinary executives keep themselves focused on their organization’s health.

Second, there is no substitute for discipline. No amount of intellectual prowess or personal charisma can make up for an inability to identify a few simple things and stick to them over time.